Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Insulin

View on Wikipedia

Insulin (/ˈɪn.sjʊ.lɪn/ ⓘ;[5][6] from Latin insula 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (INS) gene. It is the main anabolic hormone of the body.[7] It regulates the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats, and protein by promoting the absorption of glucose from the blood into cells of the liver, fat, and skeletal muscles.[8] In these tissues the absorbed glucose is converted into either glycogen, via glycogenesis, or fats (triglycerides), via lipogenesis; in the liver, glucose is converted into both.[8] Glucose production and secretion by the liver are strongly inhibited by high concentrations of insulin in the blood.[9] Circulating insulin also affects the synthesis of proteins in a wide variety of tissues. It is thus an anabolic hormone, promoting the conversion of small molecules in the blood into large molecules in the cells. Low insulin in the blood has the opposite effect, promoting widespread catabolism, especially of reserve body fat.

Beta cells are sensitive to blood sugar levels so that they secrete insulin into the blood in response to high level of glucose, and inhibit secretion of insulin when glucose levels are low.[10] Insulin production is also regulated by glucose: high glucose promotes insulin production while low glucose levels lead to lower production.[11] Insulin enhances glucose uptake and metabolism in the cells, thereby reducing blood sugar. Their neighboring alpha cells, by taking their cues from the beta cells,[10] secrete glucagon into the blood in the opposite manner: increased secretion when blood glucose is low, and decreased secretion when glucose concentrations are high. Glucagon increases blood glucose by stimulating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in the liver.[8][10] The secretion of insulin and glucagon into the blood in response to the blood glucose concentration is the primary mechanism of glucose homeostasis.[10]

Decreased or absent insulin activity results in diabetes, a condition of high blood sugar level (hyperglycaemia). There are two types of the disease. In type 1 diabetes, the beta cells are destroyed by an autoimmune reaction so that insulin can no longer be synthesized or be secreted into the blood.[12] In type 2 diabetes, the destruction of beta cells is less pronounced than in type 1, and is not due to an autoimmune process. Instead, there is an accumulation of amyloid in the pancreatic islets, which likely disrupts their anatomy and physiology.[10] The pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes is not well understood but reduced population of islet beta-cells, reduced secretory function of islet beta-cells that survive, and peripheral tissue insulin resistance are known to be involved.[7] Type 2 diabetes is characterized by increased glucagon secretion which is unaffected by, and unresponsive to the concentration of blood glucose. But insulin is still secreted into the blood in response to the blood glucose.[10] As a result, glucose accumulates in the blood.

The human insulin protein is composed of 51 amino acids, and has a molecular mass of 5808 Da. It is a heterodimer of an A-chain and a B-chain, which are linked together by disulfide bonds. Insulin's structure varies slightly between species of animals. Insulin from non-human animal sources differs somewhat in effectiveness (in carbohydrate metabolism effects) from human insulin because of these variations. Porcine insulin is especially close to the human version, and was widely used to treat type 1 diabetics before human insulin could be produced in large quantities by recombinant DNA technologies.[13][14][15][16]

Insulin was the first peptide hormone discovered.[17] Frederick Banting and Charles Best, working in the laboratory of John Macleod at the University of Toronto, were the first to isolate insulin from dog pancreas in 1921. Frederick Sanger sequenced the amino acid structure in 1951, which made insulin the first protein to be fully sequenced.[18] The crystal structure of insulin in the solid state was determined by Dorothy Hodgkin in 1969. Insulin is also the first protein to be chemically synthesised and produced by DNA recombinant technology.[19] It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[20]

Evolution and species distribution

[edit]Insulin may have originated more than a billion years ago.[21] The molecular origins of insulin go at least as far back as the simplest unicellular eukaryotes.[22] Apart from animals, insulin-like proteins are also known to exist in fungi and protists.[21]

Insulin is produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets in most vertebrates and by the Brockmann body in some teleost fish.[23] Cone snails: Conus geographus and Conus tulipa, venomous sea snails that hunt small fish, use modified forms of insulin in their venom cocktails. The insulin toxin, closer in structure to fishes' than to snails' native insulin, slows down the prey fishes by lowering their blood glucose levels.[24][25]

Production

[edit]

Insulin is produced exclusively in the beta cells of the pancreatic islets in mammals, and the Brockmann body in some fish. Human insulin is produced from the INS gene, located on chromosome 11.[26] Rodents have two functional insulin genes; one is the homolog of most mammalian genes (Ins2), and the other is a retroposed copy that includes promoter sequence but that is missing an intron (Ins1).[27] Transcription of the insulin gene increases in response to elevated blood glucose.[28] This is primarily controlled by transcription factors that bind enhancer sequences in the ~400 base pairs before the gene's transcription start site.[26][28]

The major transcription factors influencing insulin secretion are PDX1, NeuroD1, and MafA.[29][30][31][32]

During a low-glucose state, PDX1 (pancreatic and duodenal homeobox protein 1) is located in the nuclear periphery as a result of interaction with HDAC1 and 2,[33] which results in downregulation of insulin secretion.[34] An increase in blood glucose levels causes phosphorylation of PDX1, which leads it to undergo nuclear translocation and bind the A3 element within the insulin promoter.[35] Upon translocation it interacts with coactivators HAT p300 and SETD7. PDX1 affects the histone modifications through acetylation and deacetylation as well as methylation. It is also said to suppress glucagon.[36]

NeuroD1, also known as β2, regulates insulin exocytosis in pancreatic β cells by directly inducing the expression of genes involved in exocytosis.[37] It is localized in the cytosol, but in response to high glucose it becomes glycosylated by OGT and/or phosphorylated by ERK, which causes translocation to the nucleus. In the nucleus β2 heterodimerizes with E47, binds to the E1 element of the insulin promoter and recruits co-activator p300 which acetylates β2. It is able to interact with other transcription factors as well in activation of the insulin gene.[37]

MafA is degraded by proteasomes upon low blood glucose levels. Increased levels of glucose make an unknown protein glycosylated. This protein works as a transcription factor for MafA in an unknown manner and MafA is transported out of the cell. MafA is then translocated back into the nucleus where it binds the C1 element of the insulin promoter.[38][39]

These transcription factors work synergistically and in a complex arrangement. Increased blood glucose can after a while destroy the binding capacities of these proteins, and therefore reduce the amount of insulin secreted, causing diabetes. The decreased binding activities can be mediated by glucose induced oxidative stress and antioxidants are said to prevent the decreased insulin secretion in glucotoxic pancreatic β cells. Stress signalling molecules and reactive oxygen species inhibits the insulin gene by interfering with the cofactors binding the transcription factors and the transcription factors itself.[40]

Several regulatory sequences in the promoter region of the human insulin gene bind to transcription factors. In general, the A-boxes bind to Pdx1 factors, E-boxes bind to NeuroD, C-boxes bind to MafA, and cAMP response elements to CREB. There are also silencers that inhibit transcription.

Synthesis

[edit]

Insulin is synthesized as an inactive precursor molecule, a 110 amino acid-long protein called preproinsulin. Preproinsulin is translated directly into the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), where its signal peptide is removed by signal peptidase to form proinsulin.[26] As the proinsulin folds, opposite ends of the protein, called the "A-chain" and the "B-chain", are fused together with three disulfide bonds.[26] Folded proinsulin then transits through the Golgi apparatus and is packaged into specialized secretory vesicles.[26] In the granule, proinsulin is cleaved by proprotein convertase 1/3 and proprotein convertase 2, removing the middle part of the protein, called the "C-peptide".[26] Finally, carboxypeptidase E removes two pairs of amino acids from the protein's ends, resulting in active insulin – the insulin A- and B- chains, now connected with two disulfide bonds.[26]

The resulting mature insulin is packaged inside mature granules waiting for metabolic signals (such as leucine, arginine, glucose and mannose) and vagal nerve stimulation to be exocytosed from the cell into the circulation.[41]

Insulin and its related proteins have been shown to be produced inside the brain, and reduced levels of these proteins are linked to Alzheimer's disease.[42][43][44]

Insulin release is stimulated also by beta-2 receptor stimulation and inhibited by alpha-1 receptor stimulation. In addition, cortisol, glucagon and growth hormone antagonize the actions of insulin during times of stress. Insulin also inhibits fatty acid release by hormone-sensitive lipase in adipose tissue.[8]

Structure

[edit]

Contrary to an initial belief that hormones would be generally small chemical molecules, as the first peptide hormone known of its structure, insulin was found to be quite large.[17] A single protein (monomer) of human insulin is composed of 51 amino acids, and has a molecular mass of 5808 Da. The molecular formula of human insulin is C257H383N65O77S6.[45] It is a combination of two peptide chains (dimer) named an A-chain and a B-chain, which are linked together by two disulfide bonds. The A-chain is composed of 21 amino acids, while the B-chain consists of 30 residues. The linking (interchain) disulfide bonds are formed at cysteine residues between the positions A7-B7 and A20-B19. There is an additional (intrachain) disulfide bond within the A-chain between cysteine residues at positions A6 and A11. The A-chain exhibits two α-helical regions at A1-A8 and A12-A19 which are antiparallel; while the B chain has a central α -helix (covering residues B9-B19) flanked by the disulfide bond on either sides and two β-sheets (covering B7-B10 and B20-B23).[17][46]

The amino acid sequence of insulin is strongly conserved and varies only slightly between species. Bovine insulin differs from human in only three amino acid residues, and porcine insulin in one. Even insulin from some species of fish is similar enough to human to be clinically effective in humans. Insulin in some invertebrates is quite similar in sequence to human insulin, and has similar physiological effects. The strong homology seen in the insulin sequence of diverse species suggests that it has been conserved across much of animal evolutionary history. The C-peptide of proinsulin, however, differs much more among species; it is also a hormone, but a secondary one.[46]

Insulin is produced and stored in the body as a hexamer (a unit of six insulin molecules), while the active form is the monomer. The hexamer is about 36000 Da in size. The six molecules are linked together as three dimeric units to form symmetrical molecule. An important feature is the presence of zinc atoms (Zn2+) on the axis of symmetry, which are surrounded by three water molecules and three histidine residues at position B10.[17][46]

The hexamer is an inactive form with long-term stability, which serves as a way to keep the highly reactive insulin protected, yet readily available. The hexamer-monomer conversion is one of the central aspects of insulin formulations for injection. The hexamer is far more stable than the monomer, which is desirable for practical reasons; however, the monomer is a much faster-reacting drug because diffusion rate is inversely related to particle size. A fast-reacting drug means insulin injections do not have to precede mealtimes by hours, which in turn gives people with diabetes more flexibility in their daily schedules.[47] Insulin can aggregate and form fibrillar interdigitated beta-sheets. This can cause injection amyloidosis, and prevents the storage of insulin for long periods.[48]

Function

[edit]Secretion

[edit]Beta cells in the islets of Langerhans release insulin in two phases. The first-phase release is rapidly triggered in response to increased blood glucose levels, and lasts about 10 minutes. The second phase is a sustained, slow release of newly formed vesicles triggered independently of sugar, peaking in 2 to 3 hours. The two phases of the insulin release suggest that insulin granules are present in diverse stated populations or "pools". During the first phase of insulin exocytosis, most of the granules predispose for exocytosis are released after the calcium internalization. This pool is known as Readily Releasable Pool (RRP). The RRP granules represent 0.3-0.7% of the total insulin-containing granule population, and they are found immediately adjacent to the plasma membrane. During the second phase of exocytosis, insulin granules require mobilization of granules to the plasma membrane and a previous preparation to undergo their release.[49] Thus, the second phase of insulin release is governed by the rate at which granules get ready for release. This pool is known as a Reserve Pool (RP). The RP is released slower than the RRP (RRP: 18 granules/min; RP: 6 granules/min).[50] Reduced first-phase insulin release may be the earliest detectable beta cell defect predicting onset of type 2 diabetes.[51] First-phase release and insulin sensitivity are independent predictors of diabetes.[52]

The description of first phase release is as follows:

- Glucose enters the β-cells through the glucose transporters, GLUT 2. At low blood sugar levels little glucose enters the β-cells; at high blood glucose concentrations large quantities of glucose enter these cells.[53]

- The glucose that enters the β-cell is phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) by glucokinase (hexokinase IV) which is not inhibited by G-6-P in the way that the hexokinases in other tissues (hexokinase I – III) are affected by this product. This means that the intracellular G-6-P concentration remains proportional to the blood sugar concentration.[10][53]

- Glucose-6-phosphate enters glycolytic pathway and then, via the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction, into the Krebs cycle, where multiple, high-energy ATP molecules are produced by the oxidation of acetyl CoA (the Krebs cycle substrate), leading to a rise in the ATP:ADP ratio within the cell.[54]

- An increased intracellular ATP:ADP ratio closes the ATP-sensitive SUR1/Kir6.2 potassium channel (see sulfonylurea receptor). This prevents potassium ions (K+) from leaving the cell by facilitated diffusion, leading to a buildup of intracellular potassium ions. As a result, the inside of the cell becomes less negative with respect to the outside, leading to the depolarization of the cell surface membrane.

- Upon depolarization, voltage-gated calcium ion (Ca2+) channels open, allowing calcium ions to move into the cell by facilitated diffusion.

- The cytosolic calcium ion concentration can also be increased by calcium release from intracellular stores via activation of ryanodine receptors.[55]

- The calcium ion concentration in the cytosol of the beta cells can also, or additionally, be increased through the activation of phospholipase C resulting from the binding of an extracellular ligand (hormone or neurotransmitter) to a G protein-coupled membrane receptor. Phospholipase C cleaves the membrane phospholipid, phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate, into inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) then binds to receptor proteins in the plasma membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This allows the release of Ca2+ ions from the ER via IP3-gated channels, which raises the cytosolic concentration of calcium ions independently of the effects of a high blood glucose concentration. Parasympathetic stimulation of the pancreatic islets operates via this pathway to increase insulin secretion into the blood.[56]

- The significantly increased amount of calcium ions in the cells' cytoplasm causes the release into the blood of previously synthesized insulin, which has been stored in intracellular secretory vesicles.

This is the primary mechanism for release of insulin. Other substances known to stimulate insulin release include the amino acids arginine and leucine, parasympathetic release of acetylcholine (acting via the phospholipase C pathway), sulfonylurea, cholecystokinin (CCK, also via phospholipase C),[57] and the gastrointestinally derived incretins, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP).

Release of insulin is strongly inhibited by norepinephrine (noradrenaline), which leads to increased blood glucose levels during stress. It appears that release of catecholamines by the sympathetic nervous system has conflicting influences on insulin release by beta cells, because insulin release is inhibited by α2-adrenergic receptors[58] and stimulated by β2-adrenergic receptors.[59] The net effect of norepinephrine from sympathetic nerves and epinephrine from adrenal glands on insulin release is inhibition due to dominance of the α-adrenergic receptors.[60]

When the glucose level comes down to the usual physiologic value, insulin release from the β-cells slows or stops. If the blood glucose level drops lower than this, especially to dangerously low levels, release of hyperglycemic hormones (most prominently glucagon from islet of Langerhans alpha cells) forces release of glucose into the blood from the liver glycogen stores, supplemented by gluconeogenesis if the glycogen stores become depleted. By increasing blood glucose, the hyperglycemic hormones prevent or correct life-threatening hypoglycemia.

Evidence of impaired first-phase insulin release can be seen in the glucose tolerance test, demonstrated by a substantially elevated blood glucose level at 30 minutes after the ingestion of a glucose load (75 or 100 g of glucose), followed by a slow drop over the next 100 minutes, to remain above 120 mg/100 mL after two hours after the start of the test. In a normal person the blood glucose level is corrected (and may even be slightly over-corrected) by the end of the test. An insulin spike is a 'first response' to blood glucose increase, this response is individual and dose specific although it was always previously assumed to be food type specific only.

Oscillations

[edit]

Even during digestion, in general, one or two hours following a meal, insulin release from the pancreas is not continuous, but oscillates with a period of 3–6 minutes, changing from generating a blood insulin concentration more than about 800 p mol/l to less than 100 pmol/L (in rats).[61] This is thought to avoid downregulation of insulin receptors in target cells, and to assist the liver in extracting insulin from the blood.[61] This oscillation is important to consider when administering insulin-stimulating medication, since it is the oscillating blood concentration of insulin release, which should, ideally, be achieved, not a constant high concentration.[61] This may be achieved by delivering insulin rhythmically to the portal vein, by light activated delivery, or by islet cell transplantation to the liver.[61][62][63]

Blood insulin level

[edit]

The blood insulin level can be measured in international units, such as μIU/mL or in molar concentration, such as pmol/L, where 1 μIU/mL equals 6.945 pmol/L.[64] A typical blood level between meals is 8–11 μIU/mL (57–79 pmol/L).[65]

Signal transduction

[edit]The effects of insulin are initiated by its binding to a receptor, the insulin receptor (IR), present in the cell membrane. The receptor molecule contains an α- and β subunits. Two molecules are joined to form what is known as a homodimer. Insulin binds to the α-subunits of the homodimer, which faces the extracellular side of the cells. The β subunits have tyrosine kinase enzyme activity which is triggered by the insulin binding. This activity provokes the autophosphorylation of the β subunits and subsequently the phosphorylation of proteins inside the cell known as insulin receptor substrates (IRS). The phosphorylation of the IRS activates a signal transduction cascade that leads to the activation of other kinases as well as transcription factors that mediate the intracellular effects of insulin.[66]

The cascade that leads to the insertion of GLUT4 glucose transporters into the cell membranes of muscle and fat cells, and to the synthesis of glycogen in liver and muscle tissue, as well as the conversion of glucose into triglycerides in liver, adipose, and lactating mammary gland tissue, operates via the activation, by IRS-1, of phosphoinositol 3 kinase (PI3K). This enzyme converts a phospholipid in the cell membrane by the name of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), into phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), which, in turn, activates protein kinase B (PKB). Activated PKB facilitates the fusion of GLUT4 containing endosomes with the cell membrane, resulting in an increase in GLUT4 transporters in the plasma membrane.[67] PKB also phosphorylates glycogen synthase kinase (GSK), thereby inactivating this enzyme.[68] This means that its substrate, glycogen synthase (GS), cannot be phosphorylated, and remains dephosphorylated, and therefore active. The active enzyme, glycogen synthase (GS), catalyzes the rate limiting step in the synthesis of glycogen from glucose. Similar dephosphorylations affect the enzymes controlling the rate of glycolysis leading to the synthesis of fats via malonyl-CoA in the tissues that can generate triglycerides, and also the enzymes that control the rate of gluconeogenesis in the liver. The overall effect of these final enzyme dephosphorylations is that, in the tissues that can carry out these reactions, glycogen and fat synthesis from glucose are stimulated, and glucose production by the liver through glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis are inhibited.[69] The breakdown of triglycerides by adipose tissue into free fatty acids and glycerol is also inhibited.[69]

After the intracellular signal that resulted from the binding of insulin to its receptor has been produced, termination of signaling is then needed. As mentioned below in the section on degradation, endocytosis and degradation of the receptor bound to insulin is a main mechanism to end signaling.[41] In addition, the signaling pathway is also terminated by dephosphorylation of the tyrosine residues in the various signaling pathways by tyrosine phosphatases. Serine/Threonine kinases are also known to reduce the activity of insulin.

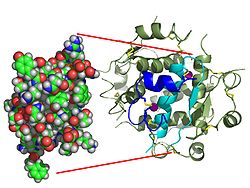

The structure of the insulin–insulin receptor complex has been determined using the techniques of X-ray crystallography.[70]

Physiological effects

[edit]

The actions of insulin on the global human metabolism level include:

- Increase of cellular intake of certain substances, most prominently glucose in muscle and adipose tissue (about two-thirds of body cells)[71]

- Increase of DNA replication and protein synthesis via control of amino acid uptake

- Modification of the activity of numerous enzymes.

The actions of insulin (indirect and direct) on cells include:

- Stimulates the uptake of glucose – Insulin decreases blood glucose concentration by inducing intake of glucose by the cells. This is possible because Insulin causes the insertion of the GLUT4 transporter in the cell membranes of muscle and fat tissues which allows glucose to enter the cell.[66]

- Increased fat synthesis – insulin forces fat cells to take in blood glucose, which is converted into triglycerides; decrease of insulin causes the reverse.[71]

- Increased esterification of fatty acids – forces adipose tissue to make neutral fats (i.e., triglycerides) from fatty acids; decrease of insulin causes the reverse.[71]

- Decreased lipolysis in – forces reduction in conversion of fat cell lipid stores into blood fatty acids and glycerol; decrease of insulin causes the reverse.[71]

- Induced glycogen synthesis – When glucose levels are high, insulin induces the formation of glycogen by the activation of the hexokinase enzyme, which adds a phosphate group in glucose, thus resulting in a molecule that cannot exit the cell. At the same time, insulin inhibits the enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase, which removes the phosphate group. These two enzymes are key for the formation of glycogen. Also, insulin activates the enzymes phosphofructokinase and glycogen synthase which are responsible for glycogen synthesis.[72]

- Decreased gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis – decreases production of glucose from noncarbohydrate substrates, primarily in the liver (the vast majority of endogenous insulin arriving at the liver never leaves the liver); decrease of insulin causes glucose production by the liver from assorted substrates.[71]

- Decreased proteolysis – decreasing the breakdown of protein[71]

- Decreased autophagy – decreased level of degradation of damaged organelles. Postprandial levels inhibit autophagy completely.[73]

- Increased amino acid uptake – forces cells to absorb circulating amino acids; decrease of insulin inhibits absorption.[71]

- Arterial muscle tone – forces arterial wall muscle to relax, increasing blood flow, especially in microarteries; decrease of insulin reduces flow by allowing these muscles to contract.[74]

- Increase in the secretion of hydrochloric acid by parietal cells in the stomach.[citation needed]

- Increased potassium uptake – forces cells synthesizing glycogen (a very spongy, "wet" substance, that increases the content of intracellular water, and its accompanying K+ ions)[75] to absorb potassium from the extracellular fluids; lack of insulin inhibits absorption. Insulin's increase in cellular potassium uptake lowers potassium levels in blood plasma. This possibly occurs via insulin-induced translocation of the Na+/K+-ATPase to the surface of skeletal muscle cells.[76][77]

- Decreased renal sodium excretion.[78]

- In hepatocytes, insulin binding acutely leads to activation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A)[citation needed], which dephosphorylates the bifunctional enzyme fructose bisphosphatase-2 (PFKB1),[79] activating the phosphofructokinase-2 (PFK-2) active site. PFK-2 increases production of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate. Fructose 2,6-bisphosphate allosterically activates PFK-1, which favors glycolysis over gluconeogenesis. Increased glycolysis increases the formation of malonyl-CoA, a molecule that can be shunted into lipogenesis and that allosterically inhibits of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1), a mitochondrial enzyme necessary for the translocation of fatty acids into the intermembrane space of the mitochondria for fatty acid metabolism.[80]

Insulin also influences other body functions, such as vascular compliance and cognition. Once insulin enters the human brain, it enhances learning and memory and benefits verbal memory in particular.[81] Enhancing brain insulin signaling by means of intranasal insulin administration also enhances the acute thermoregulatory and glucoregulatory response to food intake, suggesting that central nervous insulin contributes to the co-ordination of a wide variety of homeostatic or regulatory processes in the human body.[82] Insulin also has stimulatory effects on gonadotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus, thus favoring fertility.[83]

Degradation

[edit]Once an insulin molecule has docked onto the receptor and effected its action, it may be released back into the extracellular environment, or it may be degraded by the cell. The two primary sites for insulin clearance are the liver and the kidney.[84] It is broken down by the enzyme, protein-disulfide reductase (glutathione),[85] which breaks the disulphide bonds between the A and B chains. The liver clears most insulin during first-pass transit, whereas the kidney clears most of the insulin in systemic circulation. Degradation normally involves endocytosis of the insulin-receptor complex, followed by the action of insulin-degrading enzyme. An insulin molecule produced endogenously by the beta cells is estimated to be degraded within about one hour after its initial release into circulation (insulin half-life ~ 4–6 minutes).[86][87]

Regulator of endocannabinoid metabolism

[edit]Insulin is a major regulator of endocannabinoid (EC) metabolism and insulin treatment has been shown to reduce intracellular ECs, the 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide (AEA), which correspond with insulin-sensitive expression changes in enzymes of EC metabolism. In insulin-resistant adipocytes, patterns of insulin-induced enzyme expression is disturbed in a manner consistent with elevated EC synthesis and reduced EC degradation. Findings suggest that insulin-resistant adipocytes fail to regulate EC metabolism and decrease intracellular EC levels in response to insulin stimulation, whereby obese insulin-resistant individuals exhibit increased concentrations of ECs.[88][89] This dysregulation contributes to excessive visceral fat accumulation and reduced adiponectin release from abdominal adipose tissue, and further to the onset of several cardiometabolic risk factors that are associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes.[90]

Hypoglycemia

[edit]Hypoglycemia, also known as "low blood sugar", is when blood sugar decreases to below normal levels.[91] This may result in a variety of symptoms including clumsiness, trouble talking, confusion, loss of consciousness, seizures or death.[91] A feeling of hunger, sweating, shakiness and weakness may also be present.[91] Symptoms typically come on quickly.[91]

The most common cause of hypoglycemia is medications used to treat diabetes such as insulin and sulfonylureas.[92][93] Risk is greater in diabetics who have eaten less than usual, exercised more than usual or have consumed alcohol.[91] Other causes of hypoglycemia include kidney failure, certain tumors, such as insulinoma, liver disease, hypothyroidism, starvation, inborn error of metabolism, severe infections, reactive hypoglycemia and a number of drugs including alcohol.[91][93] Low blood sugar may occur in otherwise healthy babies who have not eaten for a few hours.[94]

Diseases and syndromes

[edit]There are several conditions in which insulin disturbance is pathologic:

- Diabetes – general term referring to all states characterized by hyperglycemia. It can be of the following types:[95]

- Type 1 diabetes – autoimmune-mediated destruction of insulin-producing β-cells in the pancreas, resulting in absolute insulin deficiency

- Type 2 diabetes – either inadequate insulin production by the β-cells or insulin resistance or both because of reasons not completely understood.

- there is correlation with diet, with sedentary lifestyle, with obesity, with age and with metabolic syndrome. Causality has been demonstrated in multiple model organisms including mice and monkeys; importantly, non-obese people do get Type 2 diabetes due to diet, sedentary lifestyle and unknown risk factors, though this may not be a causal relationship.

- it is likely that there is genetic susceptibility to develop Type 2 diabetes under certain environmental conditions

- Other types of impaired glucose tolerance (see Diabetes)

- Insulinoma – a tumor of beta cells producing excess insulin or reactive hypoglycemia.[96]

- Metabolic syndrome – a poorly understood condition first called syndrome X by Gerald Reaven. It is not clear whether the syndrome has a single, treatable cause, or is the result of body changes leading to type 2 diabetes. It is characterized by elevated blood pressure, dyslipidemia (disturbances in blood cholesterol forms and other blood lipids), and increased waist circumference (at least in populations in much of the developed world). The basic underlying cause may be the insulin resistance that precedes type 2 diabetes, which is a diminished capacity for insulin response in some tissues (e.g., muscle, fat). It is common for morbidities such as essential hypertension, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) to develop.[97]

- Polycystic ovary syndrome – a complex syndrome in women in the reproductive years where anovulation and androgen excess are commonly displayed as hirsutism. In many cases of PCOS, insulin resistance is present.[98]

Medical uses

[edit]

Biosynthetic human insulin (insulin human rDNA, INN) for clinical use is manufactured by recombinant DNA technology.[13] Biosynthetic human insulin has increased purity when compared with extractive animal insulin, enhanced purity reducing antibody formation. Researchers have succeeded in introducing the gene for human insulin into plants as another method of producing insulin ("biopharming") in safflower.[99] This technique is anticipated to reduce production costs.

Several analogs of human insulin are available. These insulin analogs are closely related to the human insulin structure, and were developed for specific aspects of glycemic control in terms of fast action (prandial insulins) and long action (basal insulins).[100] The first biosynthetic insulin analog was developed for clinical use at mealtime (prandial insulin), Humalog (insulin lispro),[101] it is more rapidly absorbed after subcutaneous injection than regular insulin, with an effect 15 minutes after injection. Other rapid-acting analogues are NovoRapid and Apidra, with similar profiles.[102] All are rapidly absorbed due to amino acid sequences that will reduce formation of dimers and hexamers (monomeric insulins are more rapidly absorbed). Fast acting insulins do not require the injection-to-meal interval previously recommended for human insulin and animal insulins. The other type is long acting insulin; the first of these was Lantus (insulin glargine). These have a steady effect for an extended period from 18 to 24 hours. Likewise, another protracted insulin analogue (Levemir) is based on a fatty acid acylation approach. A myristic acid molecule is attached to this analogue, which associates the insulin molecule to the abundant serum albumin, which in turn extends the effect and reduces the risk of hypoglycemia. Both protracted analogues need to be taken only once daily, and are used for type 1 diabetics as the basal insulin. A combination of a rapid acting and a protracted insulin is also available, making it more likely for patients to achieve an insulin profile that mimics that of the body's own insulin release.[103][104] Insulin is also used in many cell lines, such as CHO-s, HEK 293 or Sf9, for the manufacturing of monoclonal antibodies, virus vaccines, and gene therapy products.[105]

Insulin is usually taken as subcutaneous injections by single-use syringes with needles, via an insulin pump, or by repeated-use insulin pens with disposable needles. Inhaled insulin is also available in the U.S. market.

The Dispovan Single-Use Pen Needle by HMD[106] is India’s first insulin pen needle that makes self-administration easy. Featuring extra-thin walls and a multi-bevel tapered point, these pen needles prioritise patient comfort by minimising pain and ensuring seamless medication delivery. The product aims to provide affordable Pen Needles to the developing part of the country through its wide distribution channel. Additionally, the universal design of these needles guarantees compatibility with all insulin pens.

Unlike many medicines, insulin cannot be taken by mouth because, like nearly all other proteins introduced into the gastrointestinal tract, it is reduced to fragments, whereupon all activity is lost. There has been some research into ways to protect insulin from the digestive tract, so that it can be administered orally or sublingually.[107][108]

In 2021, the World Health Organization added insulin to its model list of essential medicines.[109]

Insulin, and all other medications, are supplied free of charge to people with diabetes by the National Health Service in the countries of the United Kingdom.[110]

History of study

[edit]Discovery

[edit]In 1869, while studying the structure of the pancreas under a microscope, Paul Langerhans, a medical student in Berlin, identified some previously unnoticed tissue clumps scattered throughout the bulk of the pancreas.[111] The function of the "little heaps of cells", later known as the islets of Langerhans, initially remained unknown, but Édouard Laguesse later suggested they might produce secretions that play a regulatory role in digestion.[112] Paul Langerhans' son, Archibald, also helped to understand this regulatory role.

In 1889, the physician Oskar Minkowski, in collaboration with Joseph von Mering, removed the pancreas from a healthy dog to test its assumed role in digestion. On testing the urine, they found sugar, establishing for the first time a relationship between the pancreas and diabetes. In 1901, another major step was taken by the American physician and scientist Eugene Lindsay Opie, when he isolated the role of the pancreas to the islets of Langerhans: "Diabetes mellitus when the result of a lesion of the pancreas is caused by destruction of the islets of Langerhans and occurs only when these bodies are in part or wholly destroyed".[113][114][115]

Over the next two decades researchers made several attempts to isolate the islets' secretions. In 1906 George Ludwig Zuelzer achieved partial success in treating dogs with pancreatic extract, but he was unable to continue his work. Between 1911 and 1912, E.L. Scott at the University of Chicago tried aqueous pancreatic extracts and noted "a slight diminution of glycosuria", but was unable to convince his director of his work's value; it was shut down. Israel Kleiner demonstrated similar effects at Rockefeller University in 1915, but World War I interrupted his work and he did not return to it.[116]

In 1916, Nicolae Paulescu developed an aqueous pancreatic extract which, when injected into a diabetic dog, had a normalizing effect on blood sugar levels. He had to interrupt his experiments because of World War I, and in 1921 he wrote four papers about his work carried out in Bucharest and his tests on a diabetic dog. Later that year, he published "Research on the Role of the Pancreas in Food Assimilation".[117][118]

The name "insulin" was coined by Edward Albert Sharpey-Schafer in 1916 for a hypothetical molecule produced by pancreatic islets of Langerhans (Latin insula for islet or island) that controls glucose metabolism. Unbeknown to Sharpey-Schafer, Jean de Meyer had introduced the very similar word "insuline" in 1909 for the same molecule.[119][120]

Extraction and purification

[edit]In October 1920, Canadian Frederick Banting concluded that the digestive secretions that Minkowski had originally studied were breaking down the islet secretion, thereby making it impossible to extract successfully. A surgeon by training, Banting knew that blockages of the pancreatic duct would lead most of the pancreas to atrophy, while leaving the islets of Langerhans intact. He reasoned that a relatively pure extract could be made from the islets once most of the rest of the pancreas was gone. He jotted a note to himself: "Ligate pancreatic ducts of dog. Keep dogs alive till acini degenerate leaving Islets. Try to isolate the internal secretion of these + relieve glycosurea[sic]."[121][122]

In the spring of 1921, Banting traveled to Toronto to explain his idea to John Macleod, Professor of Physiology at the University of Toronto. Macleod was initially skeptical, since Banting had no background in research and was not familiar with the latest literature, but he agreed to provide lab space for Banting to test out his ideas. Macleod also arranged for two undergraduates to be Banting's lab assistants that summer, but Banting required only one lab assistant. Charles Best and Clark Noble flipped a coin; Best won the coin toss and took the first shift. This proved unfortunate for Noble, as Banting kept Best for the entire summer and eventually shared half his Nobel Prize money and credit for the discovery with Best.[123] On 30 July 1921, Banting and Best successfully isolated an extract ("isletin") from the islets of a duct-tied dog and injected it into a diabetic dog, finding that the extract reduced its blood sugar by 40% in 1 hour.[124][122]

Banting and Best presented their results to Macleod on his return to Toronto in the fall of 1921, but Macleod pointed out flaws with the experimental design, and suggested the experiments be repeated with more dogs and better equipment. He moved Banting and Best into a better laboratory and began paying Banting a salary from his research grants. Several weeks later, the second round of experiments was also a success, and Macleod helped publish their results privately in Toronto that November. Bottlenecked by the time-consuming task of duct-tying dogs and waiting several weeks to extract insulin, Banting hit upon the idea of extracting insulin from the fetal calf pancreas, which had not yet developed digestive glands. By December, they had also succeeded in extracting insulin from the adult cow pancreas. Macleod discontinued all other research in his laboratory to concentrate on the purification of insulin. He invited biochemist James Collip to help with this task, and the team felt ready for a clinical test within a month.[122]

On 11 January 1922, Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old diabetic who lay dying at the Toronto General Hospital, was given the first injection of insulin.[125][126][127][128] However, the extract was so impure that Thompson had a severe allergic reaction, and further injections were cancelled. Over the next 12 days, Collip worked day and night to improve the ox-pancreas extract. A second dose was injected on 23 January, eliminating the glycosuria that was typical of diabetes without causing any obvious side-effects. The first American patient was Elizabeth Hughes, the daughter of U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes.[129][130] The first patient treated in the U.S. was future woodcut artist James D. Havens;[131] John Ralston Williams imported insulin from Toronto to Rochester, New York, to treat Havens.[132]

Banting and Best never worked well with Collip, regarding him as something of an interloper,[citation needed] and Collip left the project soon after. Over the spring of 1922, Best managed to improve his techniques to the point where large quantities of insulin could be extracted on demand, but the preparation remained impure. The drug firm Eli Lilly and Company had offered assistance not long after the first publications in 1921, and they took Lilly up on the offer in April. In November, Lilly's head chemist, George B. Walden discovered isoelectric precipitation and was able to produce large quantities of highly refined insulin. Shortly thereafter, insulin was offered for sale to the general public.

Patent

[edit]Toward the end of January 1922, tensions mounted between the four "co-discoverers" of insulin and Collip briefly threatened to separately patent his purification process. John G. FitzGerald, director of the non-commercial public health institution Connaught Laboratories, therefore stepped in as peacemaker. The resulting agreement of 25 January 1922 established two key conditions: 1) that the collaborators would sign a contract agreeing not to take out a patent with a commercial pharmaceutical firm during an initial working period with Connaught; and 2) that no changes in research policy would be allowed unless first discussed among FitzGerald and the four collaborators.[133] It helped contain disagreement and tied the research to Connaught's public mandate.

Initially, Macleod and Banting were particularly reluctant to patent their process for insulin on grounds of medical ethics. However, concerns remained that a private third-party would hijack and monopolize the research (as Eli Lilly and Company had hinted[134]), and that safe distribution would be difficult to guarantee without capacity for quality control. To this end, Edward Calvin Kendall gave valuable advice. He had isolated thyroxin at the Mayo Clinic in 1914 and patented the process through an arrangement between himself, the brothers Mayo, and the University of Minnesota, transferring the patent to the public university.[135] On 12 April, Banting, Best, Collip, Macleod, and FitzGerald wrote jointly to the president of the University of Toronto to propose a similar arrangement with the aim of assigning a patent to the Board of Governors of the university.[136] The letter emphasized that:[137]

The patent would not be used for any other purpose than to prevent the taking out of a patent by other persons. When the details of the method of preparation are published anyone would be free to prepare the extract, but no one could secure a profitable monopoly.

The assignment to the University of Toronto Board of Governors was completed on 15 January 1923, for the token payment of $1.00.[138] The arrangement was congratulated in The World's Work in 1923 as "a step forward in medical ethics".[139] It has also received much media attention in the 2010s regarding the issue of healthcare and drug affordability.

Following further concern regarding Eli Lilly's attempts to separately patent parts of the manufacturing process, Connaught's Assistant Director and Head of the Insulin Division Robert Defries established a patent pooling policy which would require producers to freely share any improvements to the manufacturing process without compromising affordability.[140]

Structural analysis and synthesis

[edit]Purified animal-sourced insulin was initially the only type of insulin available for experiments and diabetics. John Jacob Abel was the first to produce the crystallised form in 1926.[141] Evidence of the protein nature was first given by Michael Somogyi, Edward A. Doisy, and Philip A. Shaffer in 1924.[142] It was fully proven when Hans Jensen and Earl A. Evans Jr. isolated the amino acids phenylalanine and proline in 1935.[143]

The amino acid structure of insulin was first characterized in 1951 by Frederick Sanger,[18][144] and the first synthetic insulin was produced simultaneously in the labs of Panayotis Katsoyannis at the University of Pittsburgh and Helmut Zahn at RWTH Aachen University in the mid-1960s.[145][146][147][148][149] Synthetic crystalline bovine insulin was achieved by Chinese researchers in 1965.[150] The complete 3-dimensional structure of insulin was determined by X-ray crystallography in Dorothy Hodgkin's laboratory in 1969.[151]

Hans E. Weber discovered preproinsulin while working as a research fellow at the University of California Los Angeles in 1974. In 1973–1974, Weber learned the techniques of how to isolate, purify, and translate messenger RNA. To further investigate insulin, he obtained pancreatic tissues from a slaughterhouse in Los Angeles and then later from animal stock at UCLA. He isolated and purified total messenger RNA from pancreatic islet cells which was then translated in oocytes from Xenopus laevis and precipitated using anti-insulin antibodies. When total translated protein was run on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and sucrose gradient, peaks corresponding to insulin and proinsulin were isolated. However, to the surprise of Weber a third peak was isolated corresponding to a molecule larger than proinsulin. After reproducing the experiment several times, he consistently noted this large peak prior to proinsulin that he determined must be a larger precursor molecule upstream of proinsulin. In May 1975, at the American Diabetes Association meeting in New York, Weber gave an oral presentation of his work[152] where he was the first to name this precursor molecule "preproinsulin". Following this oral presentation, Weber was invited to dinner to discuss his paper and findings by Donald Steiner, a researcher who contributed to the characterization of proinsulin. A year later in April 1976, this molecule was further characterized and sequenced by Steiner, referencing the work and discovery of Hans Weber.[153] Preproinsulin became an important molecule to study the process of transcription and translation.

The first genetically engineered (recombinant), synthetic human[a] insulin was produced using E. coli in 1978 by Arthur Riggs and Keiichi Itakura at the Beckman Research Institute of the City of Hope in collaboration with Herbert Boyer at Genentech.[14][15] Genentech, founded by Swanson, Boyer and Eli Lilly and Company, went on in 1982 to sell the first commercially available biosynthetic human insulin under the brand name Humulin.[15] The vast majority of insulin used worldwide is biosynthetic recombinant human insulin or its analogues.[16] Recently, another recombinant approach has been used by a pioneering group of Canadian researchers, using an easily grown safflower plant, for the production of much cheaper insulin.[154]

Recombinant insulin is produced either in yeast (usually Saccharomyces cerevisiae) or E. coli. In yeast, insulin may be engineered as a single-chain protein with a KexII endoprotease (a yeast homolog of PCI/PCII) site that separates the insulin A chain from a C-terminally truncated insulin B chain. A chemically synthesized C-terminal tail containing the missing threonine is then grafted onto insulin by reverse proteolysis using the inexpensive protease trypsin;[155] typically the lysine on the C-terminal tail is protected with a chemical protecting group to prevent proteolysis. The ease of modular synthesis and the relative safety of modifications in that region accounts for common insulin analogs with C-terminal modifications (e.g. lispro, aspart, glulisine). The Genentech synthesis and completely chemical synthesis such as that by Bruce Merrifield are not preferred because the efficiency of recombining the two insulin chains is low, primarily due to competition with the precipitation of insulin B chain.

Nobel Prizes

[edit]

The Nobel Prize committee in 1923 credited the practical extraction of insulin to a team at the University of Toronto and awarded the Nobel Prize to two men: Frederick Banting and John Macleod.[156] They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1923 for the discovery of insulin. Banting, incensed that Best was not mentioned,[157] shared his prize with him, and Macleod immediately shared his with James Collip. The patent for insulin was sold to the University of Toronto for one dollar.

Two other Nobel Prizes have been awarded for work on insulin. British molecular biologist Frederick Sanger, who determined the primary structure of insulin in 1955, was awarded the 1958 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[18] Rosalyn Sussman Yalow received the 1977 Nobel Prize in Medicine for the development of the radioimmunoassay for insulin.

Several Nobel Prizes also have an indirect connection with insulin. George Minot, co-recipient of the 1934 Nobel Prize for the development of the first effective treatment for pernicious anemia, had diabetes. William Castle observed that the 1921 discovery of insulin, arriving in time to keep Minot alive, was therefore also responsible for the discovery of a cure for pernicious anemia.[158] Dorothy Hodgkin was awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964 for the development of crystallography, the technique she used for deciphering the complete molecular structure of insulin in 1969.[151]

Controversy

[edit]

The work published by Banting, Best, Collip and Macleod represented the preparation of purified insulin extract suitable for use on human patients.[159] Although Paulescu discovered the principles of the treatment, his saline extract could not be used on humans; he was not mentioned in the 1923 Nobel Prize. Ian Murray was particularly active in working to correct "the historical wrong" against Nicolae Paulescu. Murray was a professor of physiology at the Anderson College of Medicine in Glasgow, Scotland, the head of the department of Metabolic Diseases at a leading Glasgow hospital, vice-president of the British Association of Diabetes, and a founding member of the International Diabetes Federation. Murray wrote:

Insufficient recognition has been given to Paulescu, the distinguished Romanian scientist, who at the time when the Toronto team were commencing their research had already succeeded in extracting the antidiabetic hormone of the pancreas and proving its efficacy in reducing the hyperglycaemia in diabetic dogs.[160]

In a private communication, Arne Tiselius, former head of the Nobel Institute, expressed his personal opinion that Paulescu was equally worthy of the award in 1923.[161]

References

[edit]- ^ Molecularly identical to human insulin: same sequence, same set of post-translational modifications.

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000254647 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000000215 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Insulin". Lexico. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020.

- ^ "insulin". WordReference.com.

- ^ a b Voet D, Voet JG (2011). Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: Wiley.

- ^ a b c d Stryer L (1995). Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 773–74. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

- ^ Sonksen P, Sonksen J (July 2000). "Insulin: understanding its action in health and disease". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 85 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1093/bja/85.1.69. PMID 10927996.

- ^ a b c d e f g Koeslag JH, Saunders PT, Terblanche E (June 2003). "A reappraisal of the blood glucose homeostat which comprehensively explains the type 2 diabetes mellitus-syndrome X complex". The Journal of Physiology. 549 (Pt 2) (published 2003): 333–46. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.037895. PMC 2342944. PMID 12717005.

- ^ Andrali SS, Sampley ML, Vanderford NL, Ozcan S (1 October 2008). "Glucose regulation of insulin gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells". The Biochemical Journal. 415 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1042/BJ20081029. ISSN 1470-8728. PMID 18778246.

- ^ American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (1 February 2009). "Insulin Injection [". PubMed Health. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 8 July 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ a b Drug Information Portal NLM – Insulin human USAN druginfo.nlm.nih.gov Archived 19 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "First Successful Laboratory Production of Human Insulin Announced". News Release. Genentech. 6 September 1978. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Tof I (1994). "Recombinant DNA technology in the synthesis of human insulin". Little Tree Publishing. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ a b Aggarwal SR (December 2012). "What's fueling the biotech engine-2011 to 2012". Nature Biotechnology. 30 (12): 1191–7. doi:10.1038/nbt.2437. PMID 23222785. S2CID 8707897.

- ^ a b c d Weiss M, Steiner DF, Philipson LH (2000). "Insulin Biosynthesis, Secretion, Structure, and Structure-Activity Relationships". In Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Dungan K, Grossman A, et al. (eds.). Endotext. MDText.com, Inc. PMID 25905258. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ a b c Stretton AO (October 2002). "The first sequence. Fred Sanger and insulin". Genetics. 162 (2): 527–32. doi:10.1093/genetics/162.2.527. PMC 1462286. PMID 12399368.

- ^ "The discovery and development of insulin as a medical treatment can be traced back to the 19th century". Diabetes. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015) (PDF). WHO. April 2015. p. 455. hdl:10665/189763. ISBN 978-92-4-120994-6. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ a b de Souza AM, López JA (November 2004). "Insulin or insulin-like studies on unicellular organisms: a review". Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 47 (6): 973–81. doi:10.1590/S1516-89132004000600017. ISSN 1516-8913. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ LeRoith D, Shiloach J, Heffron R, Rubinovitz C, Tanenbaum R, Roth J (August 1985). "Insulin-related material in microbes: similarities and differences from mammalian insulins". Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 63 (8): 839–849. doi:10.1139/o85-106. PMID 3933801.

- ^ Wright JR, Yang H, Hyrtsenko O, Xu BY, Yu W, Pohajdak B (2014). "A review of piscine islet xenotransplantation using wild-type tilapia donors and the production of transgenic tilapia expressing a "humanized" tilapia insulin". Xenotransplantation. 21 (6): 485–95. doi:10.1111/xen.12115. PMC 4283710. PMID 25040337.

- ^ "Deadly sea snail uses weaponised insulin to make its prey sluggish". The Guardian. 19 January 2015.

- ^ Safavi-Hemami H, Gajewiak J, Karanth S, Robinson SD, Ueberheide B, Douglass AD, et al. (February 2015). "Specialized insulin is used for chemical warfare by fish-hunting cone snails". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (6): 1743–48. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.1743S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423857112. PMC 4330763. PMID 25605914.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tokarz VL, MacDonald PE, Klip A (July 2018). "The cell biology of systemic insulin function". J Cell Biol. 217 (7): 2273–2289. doi:10.1083/jcb.201802095. PMC 6028526. PMID 29622564.

- ^ Shiao MS, Liao BY, Long M, Yu HT (March 2008). "Adaptive evolution of the insulin two-gene system in mouse". Genetics. 178 (3): 1683–91. doi:10.1534/genetics.108.087023. PMC 2278064. PMID 18245324.

- ^ a b Fu Z, Gilbert ER, Liu D (January 2013). "Regulation of insulin synthesis and secretion and pancreatic Beta-cell dysfunction in diabetes". Curr Diabetes Rev. 9 (1): 25–53. doi:10.2174/157339913804143225. PMC 3934755. PMID 22974359.

- ^ Bernardo AS, Hay CW, Docherty K (November 2008). "Pancreatic transcription factors and their role in the birth, life and survival of the pancreatic beta cell" (PDF). review. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 294 (1–2): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2008.07.006. PMID 18687378. S2CID 28027796.

- ^ Rutter GA, Pullen TJ, Hodson DJ, Martinez-Sanchez A (March 2015). "Pancreatic β-cell identity, glucose sensing and the control of insulin secretion". review. The Biochemical Journal. 466 (2): 203–18. doi:10.1042/BJ20141384. PMID 25697093. S2CID 2193329.

- ^ Rutter GA, Tavaré JM, Palmer DG (June 2000). "Regulation of Mammalian Gene Expression by Glucose". review. News in Physiological Sciences. 15 (3): 149–54. doi:10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.3.149. PMID 11390898.

- ^ Poitout V, Hagman D, Stein R, Artner I, Robertson RP, Harmon JS (April 2006). "Regulation of the insulin gene by glucose and d acids". review. The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (4): 873–76. doi:10.1093/jn/136.4.873. PMC 1853259. PMID 16549443.

- ^ Vaulont S, Vasseur-Cognet M, Kahn A (October 2000). "Glucose regulation of gene transcription". review. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (41): 31555–58. doi:10.1074/jbc.R000016200. PMID 10934218.

- ^ Christensen DP, Dahllöf M, Lundh M, Rasmussen DN, Nielsen MD, Billestrup N, et al. (2011). "Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition as a novel treatment for diabetes mellitus". Molecular Medicine. 17 (5–6): 378–90. doi:10.2119/molmed.2011.00021. PMC 3105132. PMID 21274504.

- ^ Wang W, Shi Q, Guo T, Yang Z, Jia Z, Chen P, et al. (June 2016). "PDX1 and ISL1 differentially coordinate with epigenetic modifications to regulate insulin gene expression in varied glucose concentrations". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 428: 38–48. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2016.03.019. PMID 26994512.

- ^ Wang X, Wei X, Pang Q, Yi F (August 2012). "Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications in diabetes mellitus". Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2 (4): 387–95. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2012.06.005.

- ^ a b Andrali SS, Sampley ML, Vanderford NL, Ozcan S (October 2008). "Glucose regulation of insulin gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells". review. The Biochemical Journal. 415 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1042/BJ20081029. PMID 18778246.

- ^ Kaneto H, Matsuoka TA, Kawashima S, Yamamoto K, Kato K, Miyatsuka T, et al. (July 2009). "Role of MafA in pancreatic beta-cells". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 61 (7–8): 489–96. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2008.12.015. PMID 19393272.

- ^ Aramata S, Han SI, Kataoka K (December 2007). "Roles and regulation of transcription factor MafA in islet beta-cells". Endocrine Journal. 54 (5): 659–66. doi:10.1507/endocrj.KR-101. PMID 17785922.

- ^ Kaneto H, Matsuoka TA (October 2012). "Involvement of oxidative stress in suppression of insulin biosynthesis under diabetic conditions". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 13 (10): 13680–90. doi:10.3390/ijms131013680. PMC 3497347. PMID 23202973.

- ^ a b Najjar S (2003). "Insulin Action: Molecular Basis of Diabetes". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001402. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- ^ Gustin N (7 March 2005). "Researchers discover link between insulin and Alzheimer's". EurekAlert!. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ de la Monte SM, Wands JR (February 2005). "Review of insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression, signaling, and malfunction in the central nervous system: relevance to Alzheimer's disease" (PDF). Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 7 (1): 45–61. doi:10.3233/JAD-2005-7106. PMID 15750214.

- ^ Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, et al. (February 2005). "Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease—is this type 3 diabetes?" (PDF). Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 7 (1): 63–80. doi:10.3233/jad-2005-7107. PMID 15750215. S2CID 28173722.

- ^ "Insulin human". PubChem. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Fu Z, Gilbert ER, Liu D (January 2013). "Regulation of insulin synthesis and secretion and pancreatic Beta-cell dysfunction in diabetes". Current Diabetes Reviews. 9 (1): 25–53. doi:10.2174/157339913804143225. PMC 3934755. PMID 22974359.

- ^ Dunn MF (August 2005). "Zinc-ligand interactions modulate assembly and stability of the insulin hexamer -- a review". Biometals. 18 (4): 295–303. doi:10.1007/s10534-005-3685-y. PMID 16158220. S2CID 8857694.

- ^ Ivanova MI, Sievers SA, Sawaya MR, Wall JS, Eisenberg D (November 2009). "Molecular basis for insulin fibril assembly". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (45): 18990–5. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10618990I. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910080106. PMC 2776439. PMID 19864624.

- ^ Omar-Hmeadi M, Idevall-Hagren O (March 2021). "Insulin granule biogenesis and exocytosis". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 78 (5): 1957–1970. doi:10.1007/s00018-020-03688-4. PMC 7966131. PMID 33146746.

- ^ Bratanova-Tochkova TK, Cheng H, Daniel S, Gunawardana S, Liu YJ, Mulvaney-Musa J, et al. (February 2002). "Triggering and augmentation mechanisms, granule pools, and biphasic insulin secretion". Diabetes. 51 (Suppl 1): S83 – S90. doi:10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.S83. PMID 11815463.

- ^ Gerich JE (February 2002). "Is reduced first-phase insulin release the earliest detectable abnormality in individuals destined to develop type 2 diabetes?". Diabetes. 51 (Suppl 1): S117 – S121. doi:10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s117. PMID 11815469.

- ^ Lorenzo C, Wagenknecht LE, Rewers MJ, Karter AJ, Bergman RN, Hanley AJ, et al. (September 2010). "Disposition index, glucose effectiveness, and conversion to type 2 diabetes: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS)". Diabetes Care. 33 (9): 2098–2103. doi:10.2337/dc10-0165. PMC 2928371. PMID 20805282.

- ^ a b Schuit F, Moens K, Heimberg H, Pipeleers D (November 1999). "Cellular origin of hexokinase in pancreatic islets". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (46) (published 1999): 32803–09. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.46.32803. PMID 10551841.

- ^ Schuit F, De Vos A, Farfari S, Moens K, Pipeleers D, Brun T, et al. (July 1997). "Metabolic fate of glucose in purified islet cells. Glucose-regulated anaplerosis in beta cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (30) (published 1997): 18572–79. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.30.18572. PMID 9228023.

- ^ Santulli G, Pagano G, Sardu C, Xie W, Reiken S, D'Ascia SL, et al. (May 2015). "Calcium release channel RyR2 regulates insulin release and glucose homeostasis". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 125 (5): 1968–78. doi:10.1172/JCI79273. PMC 4463204. PMID 25844899.

- ^ Stryer L (1995). Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 343–44. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

- ^ Cawston EE, Miller LJ (March 2010). "Therapeutic potential for novel drugs targeting the type 1 cholecystokinin receptor". British Journal of Pharmacology. 159 (5): 1009–21. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00489.x. PMC 2839260. PMID 19922535.

- ^ Nakaki T, Nakadate T, Kato R (August 1980). "Alpha 2-adrenoceptors modulating insulin release from isolated pancreatic islets". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 313 (2): 151–53. doi:10.1007/BF00498572. PMID 6252481. S2CID 30091529.

- ^ Layden BT, Durai V, Lowe WL Jr (2010). "G-Protein-Coupled Receptors, Pancreatic Islets, and Diabetes". Nature Education. 3 (9): 13.

- ^ Sircar S (2007). Medical Physiology. Stuttgart: Thieme Publishing Group. pp. 537–38. ISBN 978-3-13-144061-7.

- ^ a b c d e Hellman B, Gylfe E, Grapengiesser E, Dansk H, Salehi A (2007). "[Insulin oscillations—clinically important rhythm. Antidiabetics should increase the pulsative component of the insulin release]". Läkartidningen (in Swedish). 104 (32–33): 2236–39. PMID 17822201.

- ^ Sarode BR, Kover K, Tong PY, Zhang C, Friedman SH (November 2016). "Light Control of Insulin Release and Blood Glucose Using an Injectable Photoactivated Depot". Molecular Pharmaceutics. 13 (11): 3835–3841. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00633. PMC 5101575. PMID 27653828.

- ^ Jain PK, Karunakaran D, Friedman SH (January 2013). "Construction of a photoactivated insulin depot" (PDF). Angewandte Chemie. 52 (5): 1404–9. doi:10.1002/anie.201207264. PMID 23208858. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Rowlett R (13 June 2001). "A Dictionary of Units of Measurement". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013.

- ^ Iwase H, Kobayashi M, Nakajima M, Takatori T (January 2001). "The ratio of insulin to C-peptide can be used to make a forensic diagnosis of exogenous insulin overdosage". Forensic Science International. 115 (1–2): 123–127. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00298-X. PMID 11056282.

- ^ a b "Handbook of Diabetes, 4th Edition, Excerpt #4: Normal Physiology of Insulin Secretion and Action". Diabetes In Control. A free weekly diabetes newsletter for Medical Professionals. 28 July 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ McManus EJ, Sakamoto K, Armit LJ, Ronaldson L, Shpiro N, Marquez R, et al. (April 2005). "Role that phosphorylation of GSK3 plays in insulin and Wnt signalling defined by knockin analysis". The EMBO Journal. 24 (8): 1571–83. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600633. PMC 1142569. PMID 15791206.

- ^ Fang X, Yu SX, Lu Y, Bast RC, Woodgett JR, Mills GB (October 2000). "Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by protein kinase A". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (22): 11960–75. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9711960F. doi:10.1073/pnas.220413597. PMC 17277. PMID 11035810.

- ^ a b Stryer L (1995). Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 351–56, 494–95, 505, 605–06, 773–75. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

- ^ Menting JG, Whittaker J, Margetts MB, Whittaker LJ, Kong GK, Smith BJ, et al. (January 2013). "How insulin engages its primary binding site on the insulin receptor". Nature. 493 (7431): 241–245. Bibcode:2013Natur.493..241M. doi:10.1038/nature11781. PMC 3793637. PMID 23302862.

Simon Lauder (9 January 2013). "Australian researchers crack insulin binding mechanism". Australian Broadcasting Commission. - ^ a b c d e f g Dimitriadis G, Mitrou P, Lambadiari V, Maratou E, Raptis SA (August 2011). "Insulin effects in muscle and adipose tissue". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 93 (Suppl 1): S52–59. doi:10.1016/S0168-8227(11)70014-6. PMID 21864752.

- ^ "Physiologic Effects of Insulin". www.vivo.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Bergamini E, Cavallini G, Donati A, Gori Z (October 2007). "The role of autophagy in aging: its essential part in the anti-aging mechanism of caloric restriction". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1114 (1): 69–78. Bibcode:2007NYASA1114...69B. doi:10.1196/annals.1396.020. PMID 17934054. S2CID 21011988.

- ^ Zheng C, Liu Z (June 2015). "Vascular function, insulin action, and exercise: an intricate interplay". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 26 (6): 297–304. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2015.02.002. PMC 4450131. PMID 25735473.

- ^ Kreitzman SN, Coxon AY, Szaz KF (July 1992). "Glycogen storage: illusions of easy weight loss, excessive weight regain, and distortions in estimates of body composition" (PDF). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 56 (Suppl 1): 292S – 93S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/56.1.292S. PMID 1615908. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2012.

- ^ Benziane B, Chibalin AV (September 2008). "Frontiers: skeletal muscle sodium pump regulation: a translocation paradigm". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 295 (3): E553–58. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.90261.2008. PMID 18430962. S2CID 10153197.

- ^ Clausen T (September 2008). "Regulatory role of translocation of Na+-K+ pumps in skeletal muscle: hypothesis or reality?". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 295 (3): E727–28, author reply 729. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.90494.2008. PMID 18775888. S2CID 13410719.

- ^ Gupta AK, Clark RV, Kirchner KA (January 1992). "Effects of insulin on renal sodium excretion". Hypertension. 19 (Suppl 1): I78–82. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.19.1_Suppl.I78. PMID 1730458.

- ^ Rider MH, Bertrand L, Vertommen D, Michels PA, Rousseau GG, Hue L (1 August 2004). "6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase: head-to-head with a bifunctional enzyme that controls glycolysis". Biochemical Journal. 381 (3): 561–579. doi:10.1042/BJ20040752. PMC 1133864. PMID 15170386.

- ^ Wang Y, Yu W, Li S, Guo D, He J, Wang Y (11 March 2022). "Acetyl-CoA Carboxylases and Diseases". Frontiers in Oncology. 12. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.836058. PMC 8963101. PMID 35359351.

- ^ Benedict C, Hallschmid M, Hatke A, Schultes B, Fehm HL, Born J, et al. (November 2004). "Intranasal insulin improves memory in humans" (PDF). Psychoneuroendocrinology. 29 (10): 1326–1334. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.04.003. PMID 15288712. S2CID 20321892.

- ^ Benedict C, Brede S, Schiöth HB, Lehnert H, Schultes B, Born J, et al. (January 2011). "Intranasal insulin enhances postprandial thermogenesis and lowers postprandial serum insulin levels in healthy men". Diabetes. 60 (1): 114–118. doi:10.2337/db10-0329. PMC 3012162. PMID 20876713.

- ^ Comninos AN, Jayasena CN, Dhillo WS (2014). "The relationship between gut and adipose hormones, and reproduction". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 153–174. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt033. PMID 24173881. S2CID 18645125.

- ^ Koh HE, Cao C, Mittendorfer B (January 2022). "Insulin Clearance in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (2): 596. doi:10.3390/ijms23020596. PMC 8776220. PMID 35054781.

- ^ "EC 1.8.4.2". iubmb.qmul.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Duckworth WC, Bennett RG, Hamel FG (October 1998). "Insulin degradation: progress and potential". Endocrine Reviews. 19 (5): 608–24. doi:10.1210/edrv.19.5.0349. PMID 9793760.

- ^ Palmer BF, Henrich WL. "Carbohydrate and insulin metabolism in chronic kidney disease". UpToDate, Inc.

- ^ D'Eon TM, Pierce KA, Roix JJ, Tyler A, Chen H, Teixeira SR (May 2008). "The role of adipocyte insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of obesity-related elevations in endocannabinoids". Diabetes. 57 (5): 1262–68. doi:10.2337/db07-1186. PMID 18276766.

- ^ Gatta-Cherifi B, Cota D (February 2016). "New insights on the role of the endocannabinoid system in the regulation of energy balance". International Journal of Obesity. 40 (2): 210–19. doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.179. PMID 26374449. S2CID 20740277.

- ^ Di Marzo V (August 2008). "The endocannabinoid system in obesity and type 2 diabetes". Diabetologia. 51 (8): 1356–67. doi:10.1007/s00125-008-1048-2. PMID 18563385.

- ^ a b c d e f "Hypoglycemia". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. October 2008. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ Yanai H, Adachi H, Katsuyama H, Moriyama S, Hamasaki H, Sako A (February 2015). "Causative anti-diabetic drugs and the underlying clinical factors for hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes". World Journal of Diabetes. 6 (1): 30–6. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i1.30. PMC 4317315. PMID 25685276.

- ^ a b Schrier RW (2007). The internal medicine casebook real patients, real answers (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-7817-6529-9. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015.

- ^ Perkin RM (2008). Pediatric hospital medicine : textbook of inpatient management (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7817-7032-3. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015.

- ^ Macdonald IA (November 2016). "A review of recent evidence relating to sugars, insulin resistance and diabetes". European Journal of Nutrition. 55 (Suppl 2): 17–23. doi:10.1007/s00394-016-1340-8. PMC 5174139. PMID 27882410.

- ^ Guettier JM, Gorden P (March 2010). "Insulin secretion and insulin-producing tumors". Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism. 5 (2): 217–227. doi:10.1586/eem.09.83. PMC 2853964. PMID 20401170.

- ^ Saklayen MG (February 2018). "The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome". Current Hypertension Reports. 20 (2) 12. doi:10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z. PMC 5866840. PMID 29480368.

- ^ El Hayek S, Bitar L, Hamdar LH, Mirza FG, Daoud G (5 April 2016). "Poly Cystic Ovarian Syndrome: An Updated Overview". Frontiers in Physiology. 7: 124. doi:10.3389/fphys.2016.00124. PMC 4820451. PMID 27092084.

- ^ Marcial GG (13 August 2007). "From SemBiosys, A New Kind Of Insulin". Inside Wall Street. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007.

- ^ Insulin analog

- ^ Vecchio I, Tornali C, Bragazzi NL, Martini M (23 October 2018). "The Discovery of Insulin: An Important Milestone in the History of Medicine". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 9: 613. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00613. PMC 6205949. PMID 30405529.

- ^ Gast K, Schüler A, Wolff M, Thalhammer A, Berchtold H, Nagel N, et al. (November 2017). "Rapid-Acting and Human Insulins: Hexamer Dissociation Kinetics upon Dilution of the Pharmaceutical Formulation". Pharmaceutical Research. 34 (11): 2270–2286. doi:10.1007/s11095-017-2233-0. PMC 5643355. PMID 28762200.

- ^ Ulrich H, Snyder B, Garg SK (2007). "Combining insulins for optimal blood glucose control in type I and 2 diabetes: focus on insulin glulisine". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 3 (3): 245–54. PMC 2293970. PMID 17703632.

- ^ Silver B, Ramaiya K, Andrew SB, Fredrick O, Bajaj S, Kalra S, et al. (April 2018). "EADSG Guidelines: Insulin Therapy in Diabetes". Diabetes Therapy. 9 (2): 449–492. doi:10.1007/s13300-018-0384-6. PMC 6104264. PMID 29508275.

- ^ "Insulin Human for innovative biologics". Novo Nordisk Pharmatech. 22 October 2021.

- ^ "क्या आप डायबिटीज के मरीज है? अगर हां तो उचित दाम में मिलेगी HMD की डिस्पोवन इंसुलिन पेन नीडल". amarujala.com. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Wong CY, Martinez J, Dass CR (2016). "Oral delivery of insulin for treatment of diabetes: status quo, challenges and opportunities". The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 68 (9): 1093–108. doi:10.1111/jphp.12607. PMID 27364922.

- ^ Shah RB, Patel M, Maahs DM, Shah VN (2016). "Insulin delivery methods: Past, present and future". International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation. 6 (1): 1–9. doi:10.4103/2230-973X.176456. PMC 4787057. PMID 27014614.

- ^ Sharma NC (1 October 2021). "WHO adds new drugs to its essential medicines' list". mint. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Free prescriptions (England)". Diabetes UK. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

If you use insulin or medicine to manage your diabetes, ... you don't pay for any item you're prescribed.

- ^ Sakula A (July 1988). "Paul Langerhans (1847-1888): a centenary tribute". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 81 (7): 414–5. doi:10.1177/014107688808100718. PMC 1291675. PMID 3045317.

- ^ Petit H. "Edouard Laguesse (1861–1927)". Museum of the Regional Hospital of Lille (in French). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Opie EL (1901). "Diabetes Mellitus Associated with Hyaline Degeneration of the islands of Langerhans of the Pancreas". Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 12 (125): 263–64. hdl:2027/coo.31924069247447.

- ^ Opie EL (1901). "On the Relation of Chronic Interstitial Pancreatitis to the Islands of Langerhans and to Diabetes Mellitus". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 5 (4): 397–428. doi:10.1084/jem.5.4.397. PMC 2118050. PMID 19866952.

- ^ Opie EL (1901). "The Relation of Diabetes Mellitus to Lesions of the Pancreas. Hyaline Degeneration of the Islands of Langerhans". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 5 (5): 527–40. doi:10.1084/jem.5.5.527. PMC 2118021. PMID 19866956.