Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Indian classical music |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

A raga[a][b] (/ˈrɑːɡə/ RAH-gə; IAST: rāga, Sanskrit: [ɾäːɡɐ]; lit. 'colouring', 'tingeing' or 'dyeing')[1][2] is a melodic framework for improvisation in Indian classical music akin to a melodic mode.[3] It is central to classical Indian music.[4] Each raga consists of an array of melodic structures with musical motifs; and, from the perspective of the Indian tradition, the resulting music has the ability to "colour the mind" as it engages the emotions of the audience.[1][2][4]

Each raga provides the musician with a musical framework within which to improvise.[3][5][6] Improvisation by the musician involves creating sequences of notes allowed by the raga in keeping with rules specific to the raga. Ragas range from small ragas like Bahar and Sahana that are not much more than songs to big ragas like Malkauns, Darbari and Yaman, which have great scope for improvisation and for which performances can last over an hour. Ragas may change over time, with an example being Marwa, the primary development of which has been going down into the lower octave, in contrast with the traditional middle octave.[7] Each raga traditionally has an emotional significance and symbolic associations such as with season, time and mood.[3] Ragas are considered a means in the Indian musical tradition for evoking specific feelings in listeners. Hundreds of ragas are recognized in the classical tradition, of which about 30 are common,[3][6] and each raga has its "own unique melodic personality".[8]

There are two main classical music traditions, Hindustani (North Indian) and Carnatic (South Indian), and the concept of raga is shared by both.[5] Raga is also found in Sikh traditions such as in Guru Granth Sahib, the primary scripture of Sikhism.[9] Similarly, it is a part of the qawwali tradition in Sufi Islamic communities of South Asia.[10] Some popular Indian film songs and ghazals use ragas in their composition.[11]

Every raga has a svara (a note or named pitch) called shadja, or adhara sadja, whose pitch may be chosen arbitrarily by the performer. This is taken to mark the beginning and end of the saptak (loosely, octave). The raga also contains an adhista, which is either the svara Ma or the svara Pa. The adhista divides the octave into two parts or anga – the purvanga, which contains lower notes, and the uttaranga, which contains higher notes. Every raga has a vadi and a samvadi. The vadi is the most prominent svara, which means that an improvising musician emphasizes or pays more attention to the vadi than to other notes. The samvadi is consonant with the vadi (always from the anga that does not contain the vadi) and is the second most prominent svara in the raga.[clarification needed]

Terminology

[edit]The Sanskrit word rāga (Sanskrit: राग) has Indian roots, as the Indo-European root *reg- connotes 'to dye'. Cognates are found in Greek, Persian, Khwarezmian, Kurdish. The words "red" and "rado" are also related.[12] According to Monier Monier-Williams, the term comes from a Sanskrit word for "the act of colouring or dyeing", or simply a "colour, hue, tint, dye".[13] The term also connotes an emotional state referring to a "feeling, affection, desire, interest, joy or delight", particularly related to passion, love, or sympathy for a subject or something.[14] In the context of ancient Indian music, the term refers to a harmonious note, melody, formula, building block of music available to a musician to construct a state of experience in the audience.[13]

The word appears in the ancient Principal Upanishads of Hinduism, as well as the Bhagavad Gita.[15] For example, verse 3.5 of the Maitri Upanishad and verse 2.2.9 of the Mundaka Upanishad contain the word rāga. The Mundaka Upanishad uses it in its discussion of soul (Atman-Brahman) and matter (Prakriti), with the sense that the soul does not "colour, dye, stain, tint" the matter.[16] The Maitri Upanishad uses the term in the sense of "passion, inner quality, psychological state".[15][17] The term rāga is also found in ancient texts of Buddhism where it connotes "passion, sensuality, lust, desire" for pleasurable experiences as one of three impurities of a character.[18][19] Alternatively, rāga is used in Buddhist texts in the sense of "color, dye, hue".[18][19][20]

![Raga groups are called thaat.[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Indiskt_That-2.jpg/250px-Indiskt_That-2.jpg)

The term rāga in the modern connotation of a melodic format occurs in the Brihaddeshi by Mataṅga Muni dated c. 8th century,[22] or possibly 9th century.[23] The Brihaddeshi describes rāga as "a combination of tones which, with beautiful illuminating graces, pleases the people in general".[24]

According to Emmie te Nijenhuis, a professor in Indian musicology, the Dattilam section of Brihaddeshi has survived into the modern times, but the details of ancient music scholars mentioned in the extant text suggest a more established tradition by the time this text was composed.[22] The same essential idea and prototypical framework is found in ancient Hindu texts, such as the Naradiyasiksa and the classic Sanskrit work Natya Shastra by Bharata Muni, whose chronology has been estimated to sometime between 500 BCE and 500 CE,[25] probably between 200 BCE and 200 CE.[26]

Bharata describes a series of empirical experiments he did with the Veena, then compared what he heard, noting the relationship of fifth intervals as a function of intentionally induced change to the instrument's tuning. Bharata states that certain combinations of notes are pleasant, and certain others are not so. His methods of experimenting with the instrument triggered further work by ancient Indian scholars, leading to the development of successive permutations, as well as theories of musical note inter-relationships, interlocking scales and how this makes the listener feel.[23] Bharata discusses Bhairava, Kaushika, Hindola, Dipaka, SrI-rāga, and Megha. Bharata states that these can to trigger a certain affection and the ability to "color the emotional state" in the audience.[13][23] His encyclopedic Natya Shastra links his studies on music to the performance arts, and it has been influential in Indian performance arts tradition.[27][28]

The other ancient text, Naradiyasiksa dated to be from the 1st century BCE, discusses secular and religious music, compares the respective musical notes.[29] This is earliest known text that reverentially names each musical note to be a deity, describing it in terms of varna ('colours') and other motifs such as parts of fingers, an approach that is conceptually similar to the 12th century Guidonian hand in European music.[29] The study that mathematically arranges rhythms and modes (rāga) has been called prastāra ('matrix').(Khan 1996, p. 89, Quote: "… the Sanskrit word prastāra, … means mathematical arrangement of rhythms and modes. In the Indian system of music there are about the 500 modes and 300 different rhythms which are used in everyday music. The modes are called Ragas.")[30]

In the ancient texts of Hinduism, the term for the technical mode part of rāga was jati. Later, jati evolved to mean quantitative class of scales, while rāga evolved to become a more sophisticated concept that included the experience of the audience.[31] A figurative sense of the word as 'passion, love, desire, delight' is also found in the Mahabharata. The specialized sense of 'loveliness, beauty', especially of voice or song, emerges in classical Sanskrit, used by Kalidasa and in the Panchatantra.[32]

History and significance

[edit]Indian classical music has ancient roots and developed to serve both spiritual (moksha) and entertainment (kama) purposes. Conceptions of sound can be traced back to the Vedic period. Sound is thought to carry a metaphysical power, thus the memorisation of Vedic texts also required precise intonation.[33]

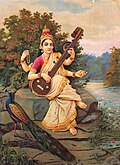

Raga, along with performance arts such as dance and music, has long been an integral part of Hinduism. Most Hindus do not regard music as merely entertainment but as a spiritual practice and path to moksha (liberation).[34][35][36] In this tradition, ragas are believed to have an inherent natural existence that is discovered rather than invented by artists.[37] Music resonates with human beings because it reflects the hidden harmonies of the ultimate creation.[37] Ancient texts such as the Sama Veda (~1000 BCE), which also arranges the Rigveda to melodic patterns,[38] are entirely structured according to melodic themes.[34][39] The ragas were envisioned by the Hindus as a manifestation of the divine, with each musical note treated as a god or goddess with complex personality.[29]

During the Bhakti movement of Hinduism, which dates to about the middle of 1st millennium CE, ragas became an integral part of the musical expression of spirituality. Bhajan and kirtan were composed and performed by the early pioneers in South India. A bhajan is a free-form devotional composition based on melodic rāgas.[40][41] A kirtan, on the other hand, is a more structured team performance, typically with a call and response musical structure, resembling an intimate conversation. It includes two or more musical instruments,[42][43] and incorporates various ragas such as those associated with Hindu gods like Shiva (Bhairav) or Krishna (Hindola).[44]

The early 13th century Sanskrit text Sangitaratnakara, by Sarngadeva patronized by King Sighana of the Yadava dynasty in the North-Central Deccan region (today a part of Maharashtra), mentions and discusses 253 ragas. This is one of the most comprehensive surviving historic treatises on the structure, technique, and reasoning behind ragas.[45][46][47]

The tradition of incorporating rāga into spiritual music is also found in Jainism[48] and in Sikhism.[49] In the Sikh scripture, the texts are set to specific raga and are sung according to the rules of that raga.[50][51] According to Pashaura Singh, a professor of Sikh and Punjabi studies, the rāga and tāla of ancient Indian traditions were carefully selected and integrated by the Sikh Gurus into their hymns. They also picked from the "standard instruments used in Hindu musical traditions" for singing kirtans in Sikhism.[51]

During the Islamic rule period of the Indian subcontinent, particularly in and after the 15th century, the mystical Islamic tradition of Sufism developed devotional songs and music called qawwali. It incorporated elements of rāga and tāla.[52][53]

The Buddha discouraged music intended for entertainment among monks seeking higher spiritual attainment, but instead encouraged chanting of sacred hymns.[54] The various canonical Tripitaka texts of Buddhism, for example, outline the Dasha-shila or ten precepts for those following the Buddhist monastic order. Among these is the precept advising monks to "abstain from dancing, singing, music and worldly spectacles".[55][56] Buddhism does not forbid music or dance for Buddhist lay followers, but its emphasis has been on chants rather than on musical raga.[54]

Description

[edit]A raga is sometimes explained as a melodic rule set that a musician works with, but according to Dorottya Fabian and others, this is now generally accepted among music scholars to be an explanation that is too simplistic. According to them, a raga of the ancient Indian tradition can be compared to the concept of non-constructible set in language for human communication, in a manner described by Frederik Kortlandt and George van Driem;[57] audiences familiar with raga recognize and evaluate performances of them intuitively.

The attempt to appreciate, understand and explain rāga among European scholars started in the early colonial period.[58] In 1784, Jones translated it as "mode" of European music tradition, but Willard corrected him in 1834 with the statement that a raga is both modet and tune. In 1933, states José Luiz Martinez – a professor of music, Stern refined this explanation to "the raga is more fixed than mode, less fixed than the melody, beyond the mode and short of melody, and richer both than a given mode or a given melody; it is mode with added multiple specialities".[58]

The raga is a central concept of Indian music, predominant in its expression, yet the concept has no direct Western translation. According to Walter Kaufmann, though a remarkable and prominent feature of Indian music, a definition of rāga cannot be offered in one or two sentences.[59] A raga is a fusion of technical and ideational ideas found in music, and may be roughly described as a musical entity that includes note intonation, relative duration and order, in a manner similar to how words flexibly form phrases to create an atmosphere of expression.[60] In some cases, certain rules are considered obligatory, in others optional. The raga allows flexibility, where the artist may rely on simple expression, or may add ornamentations yet express the same essential message but evoke a different intensity of mood.[60]

A raga has a given set of notes, on a scale, ordered in melodies with musical motifs.[6] A musician playing a raga, states Bruno Nettl, may traditionally use just these notes but is free to emphasize or improvise certain degrees of the scale.[6] The Indian tradition suggests a certain sequencing of how the musician moves from note to note for each raga, in order for the performance to create a rasa ('mood, atmosphere, essence, inner feeling') that is unique to each raga. A raga can be written on a scale. Theoretically, thousands of ragas are possibly given five or more notes, but in practical use, the classical tradition has refined and typically relies on several hundred.[6] For most artists, their basic perfected repertoire has some forty to fifty ragas.[61] Ragas in Indian classical music is intimately related to tala or guidance about "division of time", with each unit called a matra ('beat; mora').[62]

A raga is not a tune, because the same raga can yield an infinite number of tunes.[63] A raga is not a scale, because many ragas can be based on the same scale.[58][63] A raga, according to Bruno Nettl and other music scholars, is a concept similar to a mode, something between the domains of tune and scale, and it is best conceptualized as a "unique array of melodic features, mapped to and organized for a unique aesthetic sentiment in the listener".[63] The goal of a raga and its artist is to create rasa with music, as classical Indian dance does with performance arts. In the Indian tradition, classical dances are performed with music set to various ragas.[64]

Joep Bor of the Rotterdam Conservatory of Music defined rāga as a "tonal framework for composition and improvisation."[65] Nazir Jairazbhoy, chairman of UCLA's department of ethnomusicology, characterized ragas as separated by scale, line of ascent and descent, transilience, emphasized notes and register, and intonation and ornaments.[66]

Raga-Ragini system

[edit]Rāginī (रागिनी) is a term for the "feminine" counterpart of a "masculine" rāga.[67] These are envisioned to parallel the god-goddess themes in Hinduism, and described variously by different medieval Indian music scholars. For example, the Sangita-darpana text of 15th-century Damodara Misra proposes six ragas with thirty ragini, creating a system of thirty six, a system that became popular in Rajasthan.[68] In the north Himalayan regions such as Himachal Pradesh, the music scholars such as 16th century Mesakarna expanded this system to include eight descendants to each raga, thereby creating a system of eighty four. After the 16th-century, the system expanded still further.[68]

In Sangita-darpana, the Bhairava raga is associated with the following raginis: Bhairavi, Punyaki, Bilawali, Aslekhi, Bangali. In the Meskarna system, the masculine and feminine musical notes are combined to produce putra ragas called Harakh, Pancham, Disakh, Bangal, Madhu, Madhava, Lalit, Bilawal.[69]

This system is no longer in use today because the 'related' ragas had very little or no similarity and the raga-ragini classification did not agree with various other schemes.

Ragas and their symbolism

[edit]The North Indian raga system is also called Hindustani, while the South Indian system is commonly referred to as Carnatic. The North Indian system suggests a particular time of a day or a season, in the belief that the human state of psyche and mind are affected by the seasons and by daily biological cycles and nature's rhythms. The South Indian system is closer to the text, and places less emphasis on time or season.[70][71]

The symbolic role of classical music through raga has been both aesthetic indulgence and the spiritual purifying of one's mind (yoga). The former is encouraged in Kama literature (such as Kamasutra), while the latter appears in Yoga literature with concepts such as "Nada-Brahman" (metaphysical Brahman of sound).[72][73][74] Hindola raga, for example, is considered a manifestation of Kama (god of love), typically through Krishna. Hindola is also linked to the festival of dola,[72] which is more commonly known as "spring festival of colors" or Holi. This idea of aesthetic symbolism has also been expressed in Hindu temple reliefs and carvings, as well as painting collections such as the ragamala.[73]

In ancient and medieval Indian literature, the raga are described as manifestation and symbolism for gods and goddesses. Music is discussed as equivalent to the ritual yajna sacrifice, with pentatonic and hexatonic notes such as "ni-dha-pa-ma-ga-ri" as Agnistoma, "ri-ni-dha-pa-ma-ga as Asvamedha, and so on.[72]

During the Middle Ages, music scholars of India began associating each raga with seasons. The 11th-century Nanyadeva, for example, recommends that Hindola raga is best in spring, Pancama in summer, Sadjagrama and Takka during the monsoons, Bhinnasadja in early winter, and Kaisika in late winter.[75] In the 13th century, Sarngadeva went further and associated raga with rhythms of each day and night. He associated pure and simple ragas to early morning, mixed and more complex ragas to late morning, skillful ragas to noon, love-themed and passionate ragas to evening, and universal ragasl to night.[76]

Raga and Yoga Sutras

[edit]In the Yoga Sutras II.7, rāga is defined as the desire for pleasure based on remembering past experiences of pleasure. Memory triggers the wish to repeat those experiences, leading to attachment. Ego is seen as the root of this attachment, and memory is necessary for attachment to form. Even when not consciously remembered, past impressions can unconsciously draw the mind toward objects of pleasure.[77]

Raga and mathematics

[edit]According to Cris Forster, mathematical studies on systematizing and analyzing South Indian raga began in the 16th century.[78] Computational studies of rāgas is an active area of musicology.[79][80]

Notations

[edit]Although notes are an important part of raga practice, they alone do not make the raga. A raga is more than a scale, and many ragas share the same scale. The underlying scale may have four, five, six or seven tones, called svaras. The svara concept is found in the ancient Natya Shastra in Chapter 28. It calls the unit of tonal measurement or audible unit as Śruti,[81] with verse 28.21 introducing the musical scale as follows,[82]

तत्र स्वराः –

षड्जश्च ऋषभश्चैव गान्धारो मध्यमस्तथा ।

पञ्चमो धैवतश्चैव सप्तमोऽथ निषादवान् ॥ २१॥

These seven degrees are shared by both major rāga system, that is the North Indian (Hindustani) and South Indian (Carnatic).[85] The solfege (sargam) is learnt in abbreviated form: sa, ri (Carnatic) or re (Hindustani), ga, ma, pa, dha, ni, sa. Of these, the first that is "sa", and the fifth that is "pa", are considered anchors that are unalterable, while the remaining have flavors that differs between the two major systems.[85]

| Svara (Long) |

Sadja (षड्ज) |

Rishabha (ऋषभ) |

Gandhara (गान्धार) |

Madhyama (मध्यम) |

Pañcham (पञ्चम) |

Dhaivata (धैवत) |

Nishada (निषाद) |

| Svara (Short) |

Sa (सा) |

Re (रे) |

Ga (ग) |

Ma (म) |

Pa (प) |

Dha (ध) |

Ni (नि) |

| 12 Varieties (names) | C (sadja) | D♭ (komal re), D (suddha re) |

E♭ (komal ga), E (suddha ga) |

F (suddha ma), F♯ (tivra ma) |

G (pancama) | A♭ (komal dha), A (suddha dha) |

B♭ (komal ni), B (suddha ni) |

| Svara (Long) |

Shadjam (षड्ज) |

Risabham (ऋषभ) |

Gandharam (गान्धार) |

Madhyamam (मध्यम) |

Pañcamam (पञ्चम) |

Dhaivatam (धैवत) |

Nishadam (निषाद) |

| Svara (Short) |

Sa (सा) |

Ri (री) |

Ga (ग) |

Ma (म) |

Pa (प) |

Dha (ध) |

Ni (नि) |

| 16 Varieties (names) | C (sadja) | D♭ (suddha ri), D♯ (satsruti ri), D♮ (catussruti ri) |

E♭ (sadarana ga), E E♮ (antara ga) |

F♯ (prati ma), F♮ (suddha ma) |

G (pancama) | A♭ (suddha dha), A♯ (satsruti dha), A♮ (catussruti dha) |

B♭ (kaisiki ni), B B♮ (kakali ni) |

The music theory in the Natyashastra, states Maurice Winternitz, centers around three themes – sound, rhythm and prosody applied to musical texts.[88] The text asserts that the octave has 22 srutis or micro-intervals of musical tones or 1,200 cents.[81] Ancient Greek system is also very close to it, states Emmie te Nijenhuis, with the difference that each sruti computes to 54.5 cents, while the Greek enharmonic quarter-tone system computes to 55 cents.[81] The text discusses gramas (scales) and murchanas (modes), mentioning three scales of seven modes (21 total), some Greek modes are also like them .[89] However, the Gandhara-grama is just mentioned in Natyashastra, while its discussion largely focuses on two scales, fourteen modes and eight four tanas (notes).[90][91][92] The text also discusses which scales are best for different forms of performance arts.[89]

These musical elements are organized into scales (mela), and the South Indian raga system works with 72 scales, as first discussed by Caturdandi prakashika.[87] They are divided into two groups, purvanga and uttaranga, depending on the nature of the lower tetrachord. The anga itself has six cycles (cakra), where the purvanga or lower tetrachord is anchored, while there are six permutations of uttaranga suggested to the artist.[87] After this system was developed, the Indian classical music scholars have developed additional ragas for all the scales. The North Indian style is closer to the Western diatonic modes, and built upon the foundation developed by Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande using ten Thaat: kalyan, bilaval, khamaj, kafi, asavari, bhairavi, bhairav, purvi, marva and todi.[93] Some ragas are common to both systems and have same names, such as kalyan performed by either is recognizably the same.[94] Some ragas are common to both systems but have different names, such as malkos of Hindustani system is recognizably the same as hindolam of Carnatic system. However, some rāgas are named the same in the two systems, but they are different, such as todi.[94]

Recently, a 32 thaat system was presented in a book Nai Vaigyanik Paddhati to correct the classification of North Indian-style ragas.[citation needed]

Ragas containing four svaras are called surtara (सुरतर; 'tetratonic') ragas; those with five svaras are called audava (औडव; 'pentatonic') ragas; those with six are called shādava (षाडव; hextonic'); and those with seven are called sampurna (संपूर्ण; 'complete, heptatonic'). The number of svaras may differ in the ascending and descending like the Bhimpalasi raga, which has five notes in the ascending and seven notes in descending or Khamaj with six notes in the ascending and seven in the descending. Ragas differ in their ascending or descending movements. Those that do not follow the strict ascending or descending order of svaras are called vakra (वक्र; 'crooked') ragas.[citation needed]

Carnatic raga

[edit]In Carnatic music, the principal ragas are called Melakarthas, which literally means "lord of the scale". It is also called Asraya raga—meaning 'shelter-giving raga', or Janaka raga—meaning 'father raga'.[95]

A thaata in the South Indian tradition are groups of derivative rāgas, which are called Janya ('begotten') ragas or Asrita ('sheltered)' ragas.[95] However, these terms are approximate and interim phrases during learning, as the relationships between the two layers are neither fixed nor has unique parent–child relationship.[95]

Janaka ragas are grouped together using a scheme called Katapayadi sutra and are organised as Melakarta ragas. A Melakarta raga is one which has all seven notes in both the ārōhanam ('ascending scale') and avarōhanam ('descending scale'). Some Melakarta ragas are Harikambhoji, Kalyani, Kharaharapriya, Mayamalavagowla, Sankarabharanam, and Hanumatodi.[96][97] Janya ragas are derived from Janaka ragas, using a combination of the swarams (usually a subset of swarams) from the parent raga. Some janya ragas are Abheri, Abhogi, Bhairavi, Hindolam, Mohanam and Kambhoji.[96][97]

In the 21st century, few composers have discovered new ragas. Dr. M. Balamuralikrishna who has created raga in three notes[98] Ragas such as Mahathi, Lavangi, Sidhdhi, Sumukham that he created have only four notes.[99]

A list of janaka ragas would include Kanakangi, Ratnangi, Ganamurthi, Vanaspathi, Manavathi, Thanarupi, Senavathi, Hanumatodi, Dhenuka, Natakapriya, Kokilapriya, Rupavati, Gayakapriya, Vakulabharanam, Mayamalavagowla, Chakravakam, Suryakantam, Hatakambari, Jhankaradhvani, Natabhairavi, Keeravani, Kharaharapriya, Gourimanohari, Varunapriya, Mararanjani, Charukesi, Sarasangi, Harikambhoji, Sankarabharanam, Naganandini, Yagapriya, Ragavardhini, Gangeyabhushani, Vagadheeswari, Shulini, Chalanata, Salagam, Jalarnavam, Jhalavarali, Navaneetam, Pavani.

Training

[edit]Classical music has been transmitted through music schools or through Guru–Shishya parampara ('teacher–student tradition') through an oral tradition and practice. Some are known as gharana (houses), and their performances are staged through sabhas (music organizations).[100][101] Each gharana has freely improvised over time, and differences in the rendering of each raga is discernible. In the Indian musical schooling tradition, the small group of students lived near or with the teacher, the teacher treated them as family members providing food and boarding, and a student learnt various aspects of music thereby continuing the musical knowledge of their guru.[102] The tradition survives in parts of India, and many musicians can trace their guru lineage.[103]

Persian râk

[edit]The music concept of râk[clarification needed] or rang ('colour') in Persian is probably a pronunciation of rāga. According to Hormoz Farhat, it is unclear how this term came to Persia, as it has no meaning in the modern Persian language and the concept of rāga is unknown in Persia.[104][105]

See also

[edit]- List of ragas in Indian classical music

- List of composers who created ragas

- Carnatic raga

- Prahar

- Samayā

- Rasa (aesthetics)

- Raga, a documentary about the life and music of Ravi Shankar

- Raga rock

- Arabic maqam

- Persian dastgah

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Titon et al. 2008, p. 284.

- ^ a b Wilke & Moebus 2011, pp. 222 with footnote 463.

- ^ a b c d Lochtefeld 2002, p. 545.

- ^ a b Nettl et al. 1998, pp. 65–67.

- ^ a b Fabian, Renee Timmers & Emery Schubert 2014, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b c d e Nettl 2010.

- ^ Raja n.d., "Due to the influence of Amir Khan".

- ^ Hast, James R. Cowdery & Stanley Arnold Scott 1999, p. 137.

- ^ Kapoor 2005, pp. 46–52.

- ^ Salhi 2013, pp. 183–84.

- ^ Nettl et al. 1998, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Routledge. pp. 572–573. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ^ a b c Monier-Williams 1899, p. 872.

- ^ Mathur, Avantika; Vijayakumar, Suhas; Chakravarti, Bhismadev; Singh, Nandini (2015). "Emotional responses to Hindustani raga music: the role of musical structure". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 513. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00513. PMC 4415143. PMID 25983702.

- ^ a b A Concordance to the Principal Upanishads and Bhagavadgita, GA Jacob, Motilal Banarsidass, page 787

- ^ Mundaka Upanishad, Robert Hume, Oxford University Press, page 373

- ^ Maitri Upanishad, Max Muller, Oxford University Press, page 299

- ^ a b Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 59, 68, 589. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ^ a b Thomas William Rhys Davids; William Stede (1921). Pali-English Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 203, 214, 567–568, 634. ISBN 978-81-208-1144-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Damien Keown (2004). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 8, 47, 143. ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2.

- ^ Soubhik Chakraborty; Guerino Mazzola; Swarima Tewari; et al. (2014). Computational Musicology in Hindustani Music. Springer. pp. 6, 3–10. ISBN 978-3-319-11472-9.

- ^ a b Te Nijenhuis 1974, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Nettl et al. 1998, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Kaufmann 1968, p. 41.

- ^ Dace 1963, p. 249.

- ^ Lidova 2014.

- ^ Lal 2004, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Kane 1971, pp. 30–39.

- ^ a b c Te Nijenhuis 1974, p. 2.

- ^ Soubhik Chakraborty; Guerino Mazzola; Swarima Tewari; et al. (2014). Computational Musicology in Hindustani Music. Springer. pp. v–vi. ISBN 978-3-319-11472-9.;

Amiya Nath Sanyal (1959). Ragas and Raginis. Orient Longmans. pp. 18–20. - ^ Caudhurī 2000, pp. 48–50, 81.

- ^ Monier-Williams 1899.

- ^ Virani, Vivek (2019-04-11), Herbert, Ruth; Clarke, David; Clarke, Eric (eds.), "Dual consciousness and unconsciousness: The structure and spirituality of polymetric tabla compositions", Music and Consciousness 2 (1 ed.), Oxford University PressOxford, pp. 286–305, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198804352.003.0017, ISBN 978-0-19-880435-2, retrieved 2025-10-14

- ^ a b William Forde Thompson (2014). Music in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. pp. 1693–1694. ISBN 978-1-4833-6558-9.; Quote: "Some Hindus believe that music is one path to achieving moksha, or liberation from the cycle of rebirth", (...) "The principles underlying this music are found in the Samaveda, (...)".

- ^ Coormaraswamy and Duggirala (1917). "The Mirror of Gesture". Harvard University Press. p. 4.; Also see chapter 36

- ^ Beck 2012, pp. 138–139. Quote: "A summation of the signal importance of the Natyasastra for Hindu religion and culture has been provided by Susan Schwartz (2004, p. 13), 'In short, the Natyasastra is an exhaustive encyclopedic dissertation of the arts, with an emphasis on performing arts as its central feature. It is also full of invocations to deities, acknowledging the divine origins of the arts and the central role of performance arts in achieving divine goals (...)'"..

- ^ a b Dalal 2014, p. 323.

- ^ Staal 2009, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Beck 1993, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Denise Cush; Catherine Robinson; Michael York (2012). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Routledge. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-1-135-18979-2.

- ^ Nettl et al. 1998, pp. 247–253.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 371–72.

- ^ Brown 2014, p. 455, Quote:"Kirtan, (...), is the congregational singing of sacred chants and mantras in call-and-response format."; Also see, pp. 457, 474–475.

- ^ Gregory D. Booth; Bradley Shope (2014). More Than Bollywood: Studies in Indian Popular Music. Oxford University Press. pp. 65, 295–298. ISBN 978-0-19-992883-5.

- ^ Rowell 2015, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Sastri 1943, pp. v–vi, ix–x (English), for raga discussion see pp. 169–274 (Sanskrit).

- ^ Powers 1984, pp. 352–353.

- ^ Kelting 2001, pp. 28–29, 84.

- ^ Kristen Haar; Sewa Singh Kalsi (2009). Sikhism. Infobase. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-1-4381-0647-2.

- ^ Stephen Breck Reid (2001). Psalms and Practice: Worship, Virtue, and Authority. Liturgical Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-8146-5080-6.

- ^ a b Pashaura Singh (2006). Guy L. Beck (ed.). Sacred Sound: Experiencing Music in World Religions. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 156–60. ISBN 978-0-88920-421-8.

- ^ Paul Vernon (1995). Ethnic and Vernacular Music, 1898–1960: A Resource and Guide to Recordings. Greenwood Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-313-29553-9.

- ^ Regula Qureshi (1986). Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound, Context and Meaning in Qawwali. Cambridge University Press. pp. xiii, 22–24, 32, 47–53, 79–85. ISBN 978-0-521-26767-0.

- ^ a b Alison Tokita; Dr. David W. Hughes (2008). The Ashgate Research Companion to Japanese Music. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-7546-5699-9.

- ^ W. Y. Evans-Wentz (2000). The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation: Or the Method of Realizing Nirvana through Knowing the Mind. Oxford University Press. pp. 111 with footnote 3. ISBN 978-0-19-972723-0.

- ^ Frank Reynolds; Jason A. Carbine (2000). The Life of Buddhism. University of California Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-520-21105-6.

- ^ Fabian, Renee Timmers & Emery Schubert 2014, pp. 173–74.

- ^ a b c Martinez 2001, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Kaufmann 1968, p. v.

- ^ a b van der Meer 2012, pp. 3–5.

- ^ van der Meer 2012, p. 5.

- ^ van der Meer 2012, pp. 6–8.

- ^ a b c Nettl et al. 1998, p. 67.

- ^ Mehta 1995, pp. xxix, 248.

- ^ Bor et al. 1999, p. 181.

- ^ Jairazbhoy 1995, p. 45.

- ^ Dehejia 2013, pp. 191–97.

- ^ a b Dehejia 2013, pp. 168–69.

- ^ Jairazbhoy 1995, p. [page needed].

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 17–23.

- ^ Randel 2003, pp. 813–21.

- ^ a b c Te Nijenhuis 1974, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Paul Kocot Nietupski; Joan O'Mara (2011). Reading Asian Art and Artifacts: Windows to Asia on American College Campuses. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-61146-070-4.

- ^ Sastri 1943, p. xxii, Quote: "[In ancient Indian culture], the musical notes are the physical manifestations of the Highest Reality termed Nada-Brahman. Music is not a mere accompaniment in religious worship, it is religious worship itself"..

- ^ Te Nijenhuis 1974, p. 36.

- ^ Te Nijenhuis 1974, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Bryant, Edwin F. (2009-07-21). The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali: A New Edition, Translation, and Commentary with Insights from the Traditional Commentators. North Point Press. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-86547-736-0.

- ^ Forster 2010, pp. 564–565, Quote: "In the next five sections, we will examine the evolution of South Indian ragas in the writings of Ramamatya (fl. c. 1550), Venkatamakhi (fl. c. 1620), and Govinda (c. 1800). These three writers focused on a theme common to all organizational systems, namely, the principle of abstraction. Ramamatya was the first Indian theorist to formulate a system based on a mathematically determined tuning. He defined (1) a theoretical 14-tone scale, (2) a practical 12-tone tuning, and (3) a distinction between abstract mela ragas and musical janya ragas. He then combined these three concepts to identify 20 mela ragas, under which he classified more than 60 janya ragas. Venkatamakhi extended (...).".

- ^ Rao, Suvarnalata; Rao, Preeti (2014). "An Overview of Hindustani Music in the Context of Computational Musicology". Journal of New Music Research. 43 (1): 31–33. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.645.9188. doi:10.1080/09298215.2013.831109. S2CID 36631020.

- ^ Soubhik Chakraborty; Guerino Mazzola; Swarima Tewari; et al. (2014). Computational Musicology in Hindustani Music. Springer. pp. 15–16, 20, 53–54, 65–66, 81–82. ISBN 978-3-319-11472-9.

- ^ a b c Te Nijenhuis 1974, p. 14.

- ^ Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy (1985), Harmonic Implications of Consonance and Dissonance in Ancient Indian Music, Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology 2:28–51. Citation on pp. 28–31.

- ^ Sanskrit: Natyasastra Chapter 28, नाट्यशास्त्रम् अध्याय २८, ॥ २१॥

- ^ Te Nijenhuis 1974, pp. 21–25.

- ^ a b Randel 2003, pp. 814–815.

- ^ Te Nijenhuis 1974, pp. 13–14, 21–25.

- ^ a b c d Randel 2003, p. 815.

- ^ Winternitz 2008, p. 654.

- ^ a b Te Nijenhuis 1974, p. 32-34.

- ^ Te Nijenhuis 1974, pp. 14–25.

- ^ Reginald Massey; Jamila Massey (1996). The Music of India. Abhinav Publications. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-81-7017-332-8.

- ^ Richa Jain (2002). Song of the Rainbow: A Work on Depiction of Music Through the Medium of Paintings in the Indian Tradition. Kanishka. pp. 26, 39–44. ISBN 978-81-7391-496-6.

- ^ Randel 2003, pp. 815–816.

- ^ a b Randel 2003, p. 816.

- ^ a b c Caudhurī 2000, pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b Raganidhi by P. Subba Rao, Pub. 1964, The Music Academy of Madras

- ^ a b Ragas in Carnatic music by Dr. S. Bhagyalekshmy, Pub. 1990, CBH Publications

- ^ Ramakrishnan, Deepa H. (2016-11-23). "Balamurali, a legend, who created ragas with three swaras". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2021-08-11.

- ^ "Carnatic singer M Balamuralikrishna passes away in Chennai, Venkaiah Naidu offers condolences". Firstpost. 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2021-08-11.

- ^ Tenzer 2006, pp. 303–309.

- ^ Sanyukta Kashalkar-Karve (2013), "Comparative Study of Ancient Gurukul System and the New Trends of Guru-Shishya Parampara," American International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Volume 2, Number 1, pages 81–84

- ^ Nettl et al. 1998, pp. 457–467.

- ^ Ries 1969, p. 22.

- ^ Hormoz Farhat (2004). The Dastgah Concept in Persian Music. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-0-521-54206-7.

- ^ Nasrollah Nasehpour, Impact of Persian Music on Other Cultures and Vice Versa, Art of Music, Cultural, Art and Social (Monthly), pp 4--6 (Vol. 37) Sep, 2002.

Bibliography

[edit]- Beck, Guy (1993). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0872498556.

- Beck, Guy L. (2012). Sonic Liturgy: Ritual and Music in Hindu Tradition. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-61117-108-2.

- Bor, Joep; Rao, Suvarnalata; Van der Meer, Wim; Harvey, Jane (1999). The Raga Guide. Nimbus Records. ISBN 978-0-9543976-0-9.<

- Brown, Sara Black (2014). "Krishna, Christians, and Colors: The Socially Binding Influence of Kirtan Singing at a Utah Hare Krishna Festival". Ethnomusicology. 58 (3): 454–80. doi:10.5406/ethnomusicology.58.3.0454.

- Caudhurī, Vimalakānta Rôya (2000). The Dictionary of Hindustani Classical Music. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1708-1.

- Dace, Wallace (1963). "The Concept of "Rasa" in Sanskrit Dramatic Theory". Educational Theatre Journal. 15 (3): 249–254. doi:10.2307/3204783. JSTOR 3204783.

- Dalal, Roshen (2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9.

- Dehejia, Vidya (2013). The Body Adorned: Sacred and Profane in Indian Art. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51266-4.

- Fabian, Dorottya; Renee Timmers; Emery Schubert (2014). Expressiveness in music performance: Empirical approaches across styles and cultures. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-163456-7.

- Forster, Cris (2010). Musical Mathematics: On the Art and Science of Acoustic Instruments. Chronicle. ISBN 978-0-8118-7407-6. Indian Music: Ancient Beginnings – Natyashastra

- Hast, Dorothea E.; James R. Cowdery; Stanley Arnold Scott (1999). Exploring the World of Music: An Introduction to Music from a World Music Perspective. Kendall Hunt. ISBN 978-0-7872-7154-1.

- Jairazbhoy, Nazir Ali (1995). The Rāgs of North Indian Music: Their Structure & Evolution (first revised Indian ed.). Bombay: Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-395-3.

- Kane, Pandurang Vaman (1971). History of Sanskrit Poetics. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0274-2.

- Kaufmann, Walter (1968). The Ragas of North India. Oxford & Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253347800. OCLC 11369.

- Khan, Hazrat Inayat (1996). The Mysticism of Sound and Music. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-0-8348-2492-8.

- Kapoor, Sukhbir S. (2005). Guru Granth Sahib – An Advance Study. Hemkunt Press. ISBN 978-81-7010-317-2.

- Kelting, M. Whitney (2001). Singing to the Jinas: Jain Laywomen, Mandal Singing, and the Negotiations of Jain Devotion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803211-3.

- Lal, Ananda (2004). The Oxford Companion to Indian Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-564446-3.

- Lavezzoli, Peter (2006). The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1815-9.

- Lidova, Natalia (2014). Natyashastra. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0071.

- Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, 2 Volume Set. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0823922871.

- Martinez, José Luiz (2001). Semiosis in Hindustani Music. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1801-9.

- Mehta, Tarla (1995). Sanskrit Play Production in Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1057-0.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1899), A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, London: Oxford University Press

- Nettl, Bruno (2010). "Raga, Indian Musical Genre". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Nettl, Bruno; Ruth M. Stone; James Porter; Timothy Rice (1998). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1.

- Powers, Harold S. (1984). "Review: Sangita-Ratnakara of Sarngadeva, Translated by R.K. Shringy". Ethnomusicology. 28 (2): 352–355. doi:10.2307/850775. JSTOR 850775.

- Raja, Deepak S. (n.d.). "Marwa, Pooriya, and Sohini: The Tricky Triplets". Shruti.[full citation needed]

- Randel, Don Michael (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (fourth ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01163-2.

- Ries, Raymond E. (1969). "The Cultural Setting of South Indian Music". Asian Music. 1 (2): 22–31. doi:10.2307/833909. JSTOR 833909.

- Rowell, Lewis (2015). Music and Musical Thought in Early India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73034-9.

- Salhi, Kamal (2013). Music, Culture and Identity in the Muslim World: Performance, Politics and Piety. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-96310-3.

- Sastri, S.S., ed. (1943). Sangitaratnakara of Sarngadeva. Adyar: Adyar Library Press. ISBN 978-0-8356-7330-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Schwartz, Susan L. (2004). Rasa: Performing the Divine in India. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13144-5.

- Staal, Frits (2009). Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights. Auckland: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-309986-4.

- Te Nijenhuis, Emmie (1974). Indian Music: History and Structure. BRILL Academic. ISBN 978-90-04-03978-0.

- Tenzer, Michael (2006). Analytical Studies in World Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517789-3.

- Titon, Jeff Todd; Cooley; Locke; McAllester; Rasmussen (2008), Worlds of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World's Peoples, Cengage, ISBN 978-0-534-59539-5

- van der Meer, W. (2012). Hindustani Music in the 20th Century. Springer. ISBN 978-94-009-8777-7.

- Wilke, Annette; Moebus, Oliver (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

- Winternitz, Maurice (2008). History of Indian Literature Vol 3 (Original in German published in 1922, translated into English by VS Sarma, 1981). New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120800564.

Further reading

[edit]- Bhatkhande, Vishnu Narayan (1968–73). Kramika Pustaka Malika. Hathras: Sangeet Karyalaya.

- Daniélou, Alain (1949). Northern Indian Music, Volume 1. Theory & technique; Volume 2. The main rāgǎs. London: C. Johnson. OCLC 851080.

- Moutal, Patrick (2012). Hindustani Raga Index. Major bibliographical references (descriptions, compositions, vistara-s) on North Indian Raga-s. P. Moutal. ISBN 978-2-9541244-3-8.

- Moutal, Patrick (2012). Comparative Study of Selected Hindustani Ragas. P. Moutal. ISBN 978-2-9541244-2-1.

- Vatsyayan, Kapila (1977). Classical Indian dance in literature and the arts. Sangeet Natak Akademi. OCLC 233639306., Table of Contents

- Vatsyayan, Kapila (2008). Aesthetic theories and forms in Indian tradition. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-8187586357. OCLC 286469807.

External links

[edit]- A step-by-step introduction to the concept of rāga for beginners

- Rajan Parrikar Music Archive – detailed analyses of rāgas backed by rare audio recordings

- Comprehensive reference on rāgas

- Hindustani Raga Sangeet Online A rare collection of more than 800 audio & video archives from 1902. Radio programs dedicated to famous ragas.

- Online quick reference of rāgams in Carnatic music.

- Ragamath.com Mathematical computations on rāgams

Terminology and Etymology

Definition and Core Concepts

In Indian classical music, a raga serves as a melodic framework that guides improvisation, comprising a specific sequence of notes arranged in ascending (arohana) and descending (avarohana) patterns, with an emphasis on evoking distinct emotional states known as rasa.[11][12] This structure allows performers to explore variations while adhering to the raga's unique identity, distinguishing it from fixed compositions by prioritizing expressive depth over rigid notation.[3] Unlike Western scales, which are primarily harmonic building blocks, a raga incorporates rules for ornamentation, phrasing, and mood to "color" the listener's mind, as implied by its Sanskrit root meaning "to dye" or "to tint."[13] Central to the raga's construction are the swaras, the fundamental notes that form its core: Sa (shadj), Re (rishabh), Ga (gandhar), Ma (madhyam), Pa (pancham), Dha (dhaivat), and Ni (nishad).[14] These seven notes, often modified with microtonal variations (such as flat or sharp forms), provide the tonal palette, but a raga selects and emphasizes a subset to create its distinct flavor, avoiding a mere linear scale.[15] Importantly, raga focuses solely on melody and emotion, separate from tala, the cyclical rhythmic framework that organizes beats and pulses to underpin performances without dictating the melodic path.[16][17] The emotional essence of a raga is illustrated in examples like Bhairav, a morning raga whose soft, meditative phrases with flat tones mirror the tranquil serenity of dawn, fostering a sense of solemn peace and introspection.[18] This evocative quality traces back to ancient foundations, with early conceptualizations in texts like the Natya Shastra, which links melodic forms to aesthetic sentiments.[13] Through such elements, raga embodies the improvisational heart of Indian classical traditions, enabling endless artistic interpretation within defined boundaries.Linguistic and Cultural Origins

The term rāga derives from the Sanskrit root rañj, meaning "to color" or "to tint," which in a musical context signifies the evocation and infusion of specific emotions into the listener's mind.[19] This etymological sense underscores the idea of rāga as a melodic framework that "dyes" or emotionally shades the psyche, distinguishing it from mere scales by its affective dimension.[20] In ancient Indian philosophy, rāga carries a different but resonant connotation, referring to attachment, passion, or desire as one of the kleśas (afflictions) that bind the soul to the material world.[19] The Bhagavad Gītā, for instance, uses rāga multiple times to denote this emotional entanglement, such as in verses describing freedom from attachment (e.g., 2.56, 2.64, 3.34) as essential for equanimity and spiritual progress.[21] While the philosophical rāga represents an obstacle to transcendence, its musical counterpart harnesses similar emotional intensity to cultivate aesthetic experience, creating a conceptual parallel without direct overlap.[22] The terminology evolved from the melodic intonations of Vedic chants, particularly in the Sāmaveda, the earliest scriptural source emphasizing musical recitation with concepts like udātta (high pitch) and svarita (neutral tone) as foundational elements.[23] These early practices gave rise to precursors such as grāma (primary scales organizing notes) and mūrchhanā (ascending-descending modulations derived from grāma), which structured tonal frameworks in pre-classical treatises and anticipated the more nuanced rāga system.[24] By the time of classical texts, these terms had refined into a lexicon bridging ritual chant and performative art. The first documented musical application of rāga appears in Bharata Muni's Nāṭya Śāstra (c. 200 BCE–200 CE), where it denotes a "tonal color" used to evoke rasa (aesthetic emotion), linking linguistic roots to performative essence.[25]Historical Development

Ancient Foundations in Texts

The earliest documented references to melodic structures in Indian music appear in the Samaveda, one of the four Vedas composed between approximately 1500 and 500 BCE, where hymns from the Rigveda are set to specific chants known as samans, representing proto-melodic modes used in ritual performances.[26] These samans employed variations in pitch and rhythm to invoke spiritual resonance, laying foundational principles for later musical frameworks without explicit scales.[27] A significant advancement occurred in the Natya Shastra, attributed to Bharata Muni and dated to around 200 BCE to 200 CE, which introduced the concept of jatis—classified melodic forms serving as precursors to ragas—alongside the building blocks of gramas (parent scales) and murcchanas (permutations of notes derived from those scales).[28] Gramas, such as the Shadja and Madhyama, provided the scalar foundations with seven notes each, while murcchanas generated ascending and descending sequences to create diverse melodic patterns, totaling fourteen such permutations across two gramas (Shadja and Madhyama).[29] Jatis, numbering ten primary types like Oudichya and Andhri, incorporated regional and emotional variations, emphasizing ten griya (tenors) and seven sthaya (tessituras) to define melodic character.[30] Subsequent texts built on these foundations. Notably, Matanga Muni's Brihaddeshi (c. 6th–8th century CE) first defined raga as a combination of notes that "colors" the mind with specific emotions, classifying them into categories like shuddha and gandhara ragas, and listing examples such as Shadvala and Malavagaula.[31] In ancient South India, temple rituals from the early centuries CE onward integrated these Vedic and Shastric elements, with music performed during daily worship and festivals in structures like the rock-cut temples of the Pallavas (c. 600–900 CE), where chants and instrumental accompaniments influenced the evolution of melodic modes tied to devotional practices.[32] Recent archaeological evidence from the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300–1300 BCE) supports even earlier proto-musical traditions, including terracotta artifacts depicting drummers and flutes, and a 2025 discovery of third-millennium BCE copper cymbals in Oman linked to Indus trade networks, suggesting organized percussion and melodic instruments in ritual contexts.[33] By the 13th century, Sarngadeva's Sangita Ratnakara formalized raga as a distinct entity, synthesizing earlier jatis and murcchanas into structured melodic frameworks with defined ascents (arohana), descents (avarohana), and characteristic phrases, cataloging 264 ragas while preserving ancient theoretical underpinnings.[34]Evolution in Medieval and Colonial Periods

During the medieval period, Indian classical music saw significant advancements in raga theory and classification, particularly through the 13th-century treatise Sangita Ratnakara by Sarangadeva. This text systematically outlined a ten-fold classification of ragas, dividing them into marga (classical or foundational) types—such as grama ragas, upa ragas, ragas, bhasha, vibhasha, and antara bhasha—and desi (regional) types, including raganga, uparaga, ragopanga, and ganakrida. Sarangadeva described 264 distinct ragas, emphasizing their structural components like ascent (aroha) and descent (avroha), and linking them to emotional and temporal contexts, which laid the groundwork for later raga families or melodic lineages.[35] By the 16th century, Indian classical music began to diverge into the Hindustani (northern) and Carnatic (southern) traditions, influenced by regional patronage and cultural exchanges. In the north, the Mughal courts integrated Persian musical elements, such as modal structures (maqams), into existing raga frameworks, fostering hybrid forms that emphasized improvisation and emotional depth. This period marked the emergence of distinct gharanas (schools) in Hindustani music, while Carnatic music retained a stronger continuity with ancient sangita practices, focusing on composed forms and rhythmic complexity. The split was accelerated by the political fragmentation following the Delhi Sultanate and the rise of Mughal rule, which isolated northern developments from southern temple-based traditions.[36][37] A pivotal figure in this evolution was Tansen (c. 1500–1586), the renowned musician in Emperor Akbar's court, who is credited with composing several influential ragas that blended Indian and Persian sensibilities. Notable among these are Darbari Kanada (a night raga evoking devotion), Miyan ki Todi (a morning raga with introspective qualities), and Miyan ki Malhar (a rain raga), which incorporated gliding notes (meend) and expanded the melodic vocabulary of Hindustani music. Tansen's work under Akbar not only elevated court music but also symbolized cultural synthesis, as Persian influences from Mughal patronage—such as symmetrical phrasing and drone-based accompaniment—enriched raga elaboration without supplanting core Indian principles. His legacy helped establish the Gwalior gharana, one of the oldest Hindustani vocal lineages.[38][39] In the colonial era, British engagement with Indian music shifted from indifference to sporadic documentation, particularly in the 19th century, as part of broader ethnomusicological efforts to catalog colonial subjects. Administrators and scholars like William Jones and later figures such as N. Augustus Willard produced treatises and notations attempting to transcribe ragas using Western staff notation, though these often misrepresented microtonal nuances and improvisational essence. This period saw suppression of classical music in public spheres due to Victorian moral codes viewing it as decadent, yet it spurred revival movements among Indian elites. Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860–1936), a key reformer, developed the thaat system in the early 20th century to standardize Hindustani raga classification into ten parent scales (e.g., Bilaval, Khamaj, Kafi), drawing from medieval texts but adapting them for modern pedagogy and notation, which facilitated teaching and preserved diversity amid colonial disruptions.[40][41][42] Recent scholarship highlights the role of early 20th-century 78 RPM gramophone recordings in standardizing raga interpretations during the colonial twilight and independence era. These shellac discs, produced by companies like HMV from the 1900s to 1950s, captured performances by masters such as Abdul Karim Khan and Kesarbai Kerkar, fixing improvisational phrases (pakads) and tempos in audible form, which helped disseminate uniform versions across regions and influenced gharana styles. Studies from the 2020s, including archival analyses, underscore how these recordings bridged oral traditions with mechanical reproduction, aiding post-colonial revival by providing verifiable references for ragas like Yaman and Bhimpalasi, though they also inadvertently prioritized commercial appeal over fluidity.[43][44]Core Components

Melodic Framework (Swaras and Scales)

In Indian classical music, the melodic framework of a raga is built upon swaras, the fundamental musical notes that form the basis of scales and melodies. The seven primary swaras, known as sapta swaras, are Shadja (Sa), Rishabha (Re), Gandhara (Ga), Madhyama (Ma), Panchama (Pa), Dhaivata (Dha), and Nishada (Ni). These notes span an octave, or saptak, and Sa serves as the fixed tonic, providing a reference point for all others.[45][15] Swaras incorporate microtonal variations derived from shrutis, the smallest perceptible intervals in the octave. Ancient texts describe 22 shrutis per octave, allowing for nuanced pitch inflections beyond the Western semitone system; the sapta swaras are selected and positioned within these shrutis to create expressive scales. In practice, Hindustani and Carnatic traditions use 12 distinct swara positions: the seven shuddha (natural) forms, plus komal (flat or lowered) variants for Re, Ga, Dha, and Ni, and a tivra (sharp or raised) variant for Ma. Komal swaras are denoted by lowercase letters (e.g., re, ga), while tivra Ma is marked as Ma# or uppercase. These alterations enable the subtle emotional depth characteristic of ragas.[46][47] Hindustani music organizes ragas under ten thaats, parent scales proposed by musicologist Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande in the early 20th century to classify melodic structures systematically. Each thaat is a heptatonic scale using seven swaras, with variations in komal and tivra forms to derive specific ragas. The thaats are derived from combinations of the 12 swara positions, prioritizing shuddha notes as a baseline while incorporating alterations for diversity. Below is a table summarizing the ten thaats and their swara compositions (where uppercase denotes shuddha, lowercase komal, and M# tivra):| Thaat | Arohana Swaras | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Kalyan | S R G M# P D N S | Evening ragas; tivra Ma emphasized. |

| Bilawal | S R G M P D N S | All shuddha; bright, major-like scale. |

| Khamaj | S R G M P D n S | Komal Ni; semi-classical associations. |

| Kafi | S R g M P D n S | Komal Ga and Ni; folk-influenced. |

| Asavari | S R g M P d n S | Komal Ga, Dha, Ni; morning ragas. |

| Bhairavi | S r g M P d n S | All variable swaras komal; devotional. |

| Bhairav | S r G M P d N S | Komal Re and Dha; dawn evocation. |

| Marwa | S r G M# P D N S | Komal Re; tivra Ma; intense. |

| Poorvi | S r G M# P d N S | Komal Re and Dha; tivra Ma; profound. |

| Todi | S r g M# P d N S | Komal Re, Ga, Dha; complex variations. |