Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Peripheral nervous system

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

| Peripheral nervous system | |

|---|---|

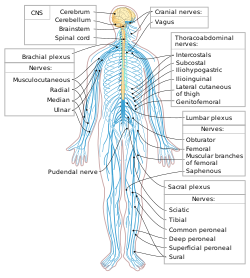

The human nervous system. Sky blue is PNS; yellow is CNS. | |

| Identifiers | |

| Acronym | PNS |

| MeSH | D017933 |

| TA98 | A14.2.00.001 |

| TA2 | 6129 |

| FMA | 9093 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is one of two components that make up the nervous system of bilateral animals, with the other part being the central nervous system (CNS). The PNS consists of nerves and ganglia, which lie outside the brain and the spinal cord.[1] The main function of the PNS is to connect the CNS to the limbs and organs, essentially serving as a relay between the brain and spinal cord and the rest of the body.[2] Unlike the CNS, the PNS is not protected by the vertebral column and skull, or by the blood–brain barrier, which leaves it exposed to toxins.[3]

The peripheral nervous system can be divided into a somatic division and an autonomic division. Each of these can further be differentiated into a sensory and a motor sector.[4] In the somatic nervous system, the cranial nerves are part of the PNS with the exceptions of the olfactory nerve and epithelia and the optic nerve (cranial nerve II) along with the retina, which are considered parts of the central nervous system based on developmental origin. The second cranial nerve is not a true peripheral nerve but a tract of the diencephalon.[5] Cranial nerve ganglia, as with all ganglia, are part of the PNS.[6] The autonomic nervous system exerts involuntary control over smooth muscle and glands.[7]

Structure

[edit]The peripheral nervous system can be divided into a somatic and an autonomic division, which are part of the somatic nervous system and the autonomic nervous system, respectively. The somatic nervous system is under voluntary control, and transmits signals from the brain to end organs such as muscles. The sensory nervous system is part of the somatic nervous system and transmits signals from senses such as taste and touch (including fine touch and gross touch) to the spinal cord and brain. The autonomic nervous system is a "self-regulating" system which influences the function of organs outside voluntary control, such as the heart rate, or the functions of the digestive system.

Somatic nervous system

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

The somatic nervous system includes the sensory nervous system (ex. the somatosensory system) and consists of sensory nerves and somatic nerves, and many nerves which hold both functions.

In the head and neck, cranial nerves carry somatosensory data. There are twelve cranial nerves, ten of which originate from the brainstem, and mainly control the functions of the anatomic structures of the head with some exceptions. One unique cranial nerve is the vagus nerve, which receives sensory information from organs in the thorax and abdomen. The other unique cranial nerve is the accessory nerve which is responsible for innervating the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, neither of which are located exclusively in the head.

For the rest of the body, spinal nerves are responsible for somatosensory information. These arise from the spinal cord. Usually these arise as a web ("plexus") of interconnected nerves roots that arrange to form single nerves. These nerves control the functions of the rest of the body. In humans, there are 31 pairs of spinal nerves: 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 1 coccygeal. These nerve roots are named according to the spinal vertebrata which they are adjacent to. In the cervical region, the spinal nerve roots come out above the corresponding vertebrae (i.e., nerve root between the skull and 1st cervical vertebrae is called spinal nerve C1). From the thoracic region to the coccygeal region, the spinal nerve roots come out below the corresponding vertebrae. This method creates a problem when naming the spinal nerve root between C7 and T1 (so it is called spinal nerve root C8). In the lumbar and sacral region, the spinal nerve roots travel within the dural sac and they travel below the level of L2 as the cauda equina.

Cervical spinal nerves (C1–C4)

[edit]The first 4 cervical spinal nerves, C1 through C4, split and recombine to produce a variety of nerves that serve the neck and back of head.

Spinal nerve C1 is called the suboccipital nerve, which provides motor innervation to muscles at the base of the skull. C2 and C3 form many of the nerves of the neck, providing both sensory and motor control. These include the greater occipital nerve, which provides sensation to the back of the head, the lesser occipital nerve, which provides sensation to the area behind the ears, the greater auricular nerve and the lesser auricular nerve.

The phrenic nerve is a nerve essential for our survival which arises from nerve roots C3, C4 and C5. It supplies the thoracic diaphragm, enabling breathing. If the spinal cord is transected above C3, then spontaneous breathing is not possible.[citation needed]

Brachial plexus (C5–T1)

[edit]The last four cervical spinal nerves, C5 through C8, and the first thoracic spinal nerve, T1, combine to form the brachial plexus, or plexus brachialis, a tangled array of nerves, splitting, combining and recombining, to form the nerves that subserve the upper-limb and upper back. Although the brachial plexus may appear tangled, it is highly organized and predictable, with little variation between people. See brachial plexus injuries.

Lumbosacral plexus (L1–Co1)

[edit]The anterior divisions of the lumbar nerves, sacral nerves, and coccygeal nerve form the lumbosacral plexus, the first lumbar nerve being frequently joined by a branch from the twelfth thoracic. For descriptive purposes this plexus is usually divided into three parts:

Autonomic nervous system

[edit]The autonomic nervous system (ANS) controls involuntary responses to regulate physiological functions.[8] The brain and spinal cord of the central nervous system are connected with organs that have smooth muscle or cardiac muscle, such as the heart, bladder, and other cardiac, exocrine, and endocrine related organs, by ganglionic neurons.[8] The most notable physiological effects from autonomic activity are pupil constriction and dilation, and salivation of saliva.[8] The autonomic nervous system is always activated, but is either in the sympathetic or parasympathetic state.[8] Depending on the situation, one state can overshadow the other, resulting in a release of different kinds of neurotransmitters.[8]

Sympathetic nervous system

[edit]The sympathetic system is activated during a "fight or flight" situation in which mental stress or physical danger is encountered.[8] Neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, and epinephrine are released,[8] which increases heart rate and blood flow in certain areas like muscle, while simultaneously decreasing activities of non-critical functions for survival, like digestion.[9] The systems are independent to each other, which allows activation of certain parts of the body, while others remain rested.[9]

Parasympathetic nervous system

[edit]Primarily using the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) as a mediator, the parasympathetic system allows the body to function in a "rest and digest" state.[9] Consequently, when the parasympathetic system dominates the body, there are increases in salivation and activities in digestion, while heart rate and other sympathetic response decrease.[9] Unlike the sympathetic system, humans have some voluntary controls in the parasympathetic system. The most prominent examples of this control are urination and defecation.[9]

Enteric nervous system

[edit]There is a lesser known division of the autonomic nervous system known as the enteric nervous system.[9] Located only around the digestive tract, this system allows for local control without input from the sympathetic or the parasympathetic branches, though it can still receive and respond to signals from the rest of the body.[9] The enteric system is responsible for various functions related to gastrointestinal system.[9]

Disease

[edit]Diseases of the peripheral nervous system can be specific to one or more nerves, or affect the system as a whole.

Any peripheral nerve or nerve root can be damaged, called a mononeuropathy. Such injuries can be because of injury or trauma, or compression. Compression of nerves can occur because of a tumour mass or injury. Alternatively, if a nerve is in an area with a fixed size it may be trapped if the other components increase in size, such as carpal tunnel syndrome and tarsal tunnel syndrome. Common symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome include pain and numbness in the thumb, index and middle finger. In peripheral neuropathy, the function one or more nerves are damaged through a variety of means. Toxic damage may occur because of diabetes (diabetic neuropathy), alcohol, heavy metals or other toxins; some infections; autoimmune and inflammatory conditions such as amyloidosis and sarcoidosis.[8] Peripheral neuropathy is associated with a sensory loss in a "glove and stocking" distribution that begins at the peripheral and slowly progresses upwards, and may also be associated with acute and chronic pain. Peripheral neuropathy is not just limited to the somatosensory nerves, but the autonomic nervous system too (autonomic neuropathy).[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Alberts, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 1862. ISBN 9781416062578.

- ^ "Slide show: How your brain works - Mayo Clinic". mayoclinic.com. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Aspromonte, John (2019). ADHD : the ultimate teen guide. Lanham. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-5381-0039-4. OCLC 1048014796.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Saladin, Kenneth (2024). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill. p. 1076. ISBN 9781266041846.

- ^ Board Review Series: Neuroanatomy, 4th Ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Maryland 2008, p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7817-7245-7.

- ^ James S. White (21 March 2008). Neurobioscitifity. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-07-149623-0. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ Campbell biology. Lisa A. Urry, Michael L. Cain, Steven Alexander Wasserman, Peter V. Minorsky, Rebecca B. Orr, Neil A. Campbell (12th ed.). New York, NY. 2021. ISBN 978-0-13-518874-3. OCLC 1119065904.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Laight, David (September 2013). "Overview of peripheral nervous system pharmacology". Nurse Prescribing. 11 (9): 448–454. doi:10.12968/npre.2013.11.9.448. ISSN 1479-9189.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Matic, Agnella Izzo (2014). "Introduction to the Nervous System, Part 2: The Autonomic Nervous System and the Central Nervous System". AMWA Journal: American Medical Writers Association Journal (AMWA J). ISSN 1075-6361.[permanent dead link]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

External links

[edit]- Peripheral nervous system photomicrographs

- Peripheral Neuropathy Archived 2016-12-15 at the Wayback Machine from the US NIH

- Neuropathy: Causes, Symptoms and Treatments from Medical News Today

- Peripheral Neuropathy at the Mayo Clinic

Peripheral nervous system

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and components

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) encompasses all neural structures located outside the brain and spinal cord, which collectively constitute the central nervous system (CNS). It functions as the primary conduit for communication between the CNS and the body's peripheral tissues, organs, and extremities.[1][10] Key components of the PNS include 12 pairs of cranial nerves—excluding the optic (II) and olfactory (I) nerves, which are direct extensions of the CNS—and 31 pairs of spinal nerves, totaling 41 pairs of peripheral nerves.[11] These nerves incorporate sensory (afferent) neurons that relay information from sensory receptors toward the CNS and motor (efferent) neurons that transmit commands from the CNS to target effectors like muscles and glands. The PNS also features ganglia, which are aggregations of neuronal cell bodies situated outside the CNS, serving as relay and processing stations for neural signals.[6][12][13] The PNS is broadly divided into the somatic nervous system, responsible for voluntary control of skeletal muscles and sensory perception from the external environment, and the autonomic nervous system, which governs involuntary regulation of visceral organs, smooth muscles, and glands. The autonomic division comprises three subsystems: the sympathetic nervous system, which mobilizes the body during stress; the parasympathetic nervous system, which promotes conservation and restoration; and the enteric nervous system, which manages gastrointestinal functions. This organization facilitates bidirectional connectivity, with afferent pathways delivering sensory data to the CNS and efferent pathways distributing motor instructions to the periphery.[5][7][14]Distinction from central nervous system

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is anatomically distinguished from the central nervous system (CNS) primarily by its location and structural exposure. The CNS, comprising the brain and spinal cord, is encased within protective bony structures such as the skull and vertebral column, which shield it from mechanical trauma.[10] In contrast, the PNS consists of nerves and ganglia that extend beyond these enclosures, branching out to innervate peripheral tissues including muscles, skin, and organs throughout the body, leaving it more susceptible to external damage.[10][15] Functionally, the CNS serves as the primary site for information integration and higher-order processing, where sensory inputs are analyzed and motor outputs are coordinated to generate complex responses. The PNS, however, primarily facilitates the transmission of sensory signals to the CNS and motor commands from the CNS to effectors, enabling direct communication between the central processors and the body's periphery. Additionally, the PNS supports local reflex arcs, such as spinal reflexes, which allow rapid, automatic responses to stimuli without requiring CNS involvement, thereby bypassing the brain for quicker execution.[16] Protection mechanisms further differentiate the two systems. The CNS is safeguarded by the blood-brain barrier, which selectively regulates substance passage into neural tissue, and by the meninges—a triple-layered connective tissue envelope that provides cushioning and compartmentalization.[10] The PNS lacks these features but employs its own connective tissue sheaths for nerve protection: the endoneurium surrounds individual axons, the perineurium bundles axons into fascicles, and the epineurium encases entire nerves, collectively forming a blood-nerve barrier analogous to the blood-brain barrier but less impermeable.[17][15] From an evolutionary perspective, the PNS's decentralized architecture promotes rapid environmental adaptation by distributing control through peripheral reflexes and sensory feedback, allowing organisms to respond efficiently to immediate threats or opportunities without relying solely on centralized CNS processing.[18] This design enhances survival in dynamic habitats, as seen in the modular neural networks that enable adaptive locomotion in invertebrates and vertebrates alike.[18]Anatomy

Cranial nerves

The cranial nerves III through XII constitute the peripheral components of the cranial nervous system, originating from the brainstem and serving as primary conduits for sensory input and motor output to structures in the head and neck. These ten pairs of nerves emerge from distinct regions of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata, traversing intracranial and extracranial pathways before exiting the cranium via specific foramina. Their functions encompass pure motor control (e.g., eye and tongue movements), sensory perception (e.g., facial sensation and hearing), and mixed modalities, including visceral regulation, thereby facilitating essential activities such as vision, facial expression, and swallowing. Unlike the olfactory (I) and optic (II) nerves, which are considered central nervous system extensions, nerves III–XII are unequivocally peripheral, with their cell bodies located outside the brainstem.[19] The oculomotor nerve (III) arises from the midbrain at the level of the superior colliculus, forming a short intracranial course through the interpeduncular cistern before entering the cavernous sinus and exiting the skull via the superior orbital fissure. Extracranially, it divides into superior and inferior branches that innervate extraocular muscles, including the levator palpebrae superioris for eyelid elevation. Primarily motor, it supplies somatic innervation to four extraocular muscles (superior rectus, inferior rectus, medial rectus, and inferior oblique) and parasympathetic fibers to the ciliary ganglion for pupillary constriction and lens accommodation, though the latter integrates briefly with autonomic pathways.[19][20] The trochlear nerve (IV), the smallest cranial nerve, originates from the midbrain dorsal to the superior colliculus—the only cranial nerve to emerge posteriorly—and travels a long intracranial path around the cerebral peduncle, through the cavernous sinus, to exit via the superior orbital fissure. Its extracranial segment is short, directly innervating the superior oblique muscle of the eye for downward and inward gaze. It is purely motor, with no sensory component.[19][21] The trigeminal nerve (V), the largest cranial nerve, emerges from the pons as a large sensory root and smaller motor root, coursing anteriorly in the middle cranial fossa to the trigeminal ganglion in Meckel's cave. From there, it divides into three extracranial branches: ophthalmic (exiting via superior orbital fissure for forehead and eye sensation), maxillary (via foramen rotundum for midface sensation), and mandibular (via foramen ovale for lower face sensation and motor to masticatory muscles). It is mixed, providing sensory innervation to the face, mouth, and meninges while motor supply to the muscles of mastication.[19][22] The abducens nerve (VI) originates from the pons near the pontomedullary junction, traveling a vulnerable intracranial course along the clivus and through the cavernous sinus to exit via the superior orbital fissure. Extracranially, it innervates the lateral rectus muscle for eye abduction. It is purely motor, dedicated to lateral gaze.[19][20] The facial nerve (VII) arises from the pontomedullary junction, entering the internal acoustic meatus with the vestibulocochlear nerve before turning sharply at the geniculum in the facial canal of the temporal bone. It exits the skull via the stylomastoid foramen, branching extracranially to supply facial expression muscles, stapedius for sound attenuation, and anterior tongue taste buds via the chorda tympani. Mixed in function, it provides motor innervation to facial muscles, parasympathetic to salivary and lacrimal glands, and sensory for taste and ear sensation.[19][21] The vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII), focusing on its peripheral component, originates from the pontomedullary junction and travels through the internal acoustic meatus alongside VII, with cochlear and vestibular divisions separating extracranially to innervate the cochlea for hearing and semicircular canals/otoliths for balance. It is purely sensory, transmitting auditory and vestibular information.[19][23] The glossopharyngeal nerve (IX) emerges from the medulla in the postolivary sulcus, joining the vagus and accessory nerves in a sheath to exit via the jugular foramen. Its extracranial path includes tympanic and carotid branches, innervating the pharynx, tongue, and carotid body. Mixed, it carries general sensation from the posterior tongue and pharynx, special taste sensation, and motor/parasympathetic to the stylopharyngeus muscle and parotid gland.[19][24] The vagus nerve (X), the longest cranial nerve, arises from the medulla in the same rootlets as IX, traveling through the jugular foramen and descending through the neck, thorax, and abdomen in the carotid sheath. Extracranially, it branches extensively to innervate the larynx, pharynx, heart, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract up to the splenic flexure. Mixed, it provides sensory from thoracic and abdominal viscera, motor to pharyngeal/laryngeal muscles, and extensive parasympathetic control to visceral organs.[19][1] The accessory nerve (XI) originates from the medulla and upper cervical spinal cord (C1–C5), with cranial and spinal roots uniting briefly before the cranial root merges with X; the spinal root exits via the jugular foramen and descends in the neck to innervate the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It is purely motor, controlling head rotation and shoulder elevation.[19][21] The hypoglossal nerve (XII) emerges from the medulla between the pyramid and olive, exiting the skull via the hypoglossal canal and traveling extracranially along the carotid artery to branch into the tongue musculature. It is purely motor, innervating intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles for speech, swallowing, and mastication.[25][19]Spinal nerves and plexuses

The peripheral nervous system's spinal nerves consist of 31 pairs that emerge from the spinal cord, providing motor and sensory innervation to the body trunk and limbs. These nerves are organized segmentally: eight cervical pairs (C1–C8), twelve thoracic pairs (T1–T12), five lumbar pairs (L1–L5), five sacral pairs (S1–S5), and one coccygeal pair (Co1).[26] Each spinal nerve forms by the union of a dorsal root, which carries sensory (afferent) fibers from the periphery to the spinal cord, and a ventral root, which conveys motor (efferent) fibers from the spinal cord to the periphery.[26] The dorsal root contains a dorsal root ganglion housing the cell bodies of sensory neurons, while the ventral root lacks such a structure.[26] Immediately after exiting the intervertebral foramen, each spinal nerve divides into four primary branches: the dorsal ramus, ventral ramus, meningeal ramus, and communicating rami. The dorsal ramus supplies the intrinsic muscles and skin of the back, while the ventral ramus innervates the anterior and lateral trunk as well as the limbs.[27] The meningeal ramus re-enters the vertebral canal to provide sensory and vasomotor innervation to the meninges and blood vessels, and the communicating rami connect the spinal nerve to the sympathetic chain ganglia for autonomic functions.[27] In regions requiring complex innervation, the ventral rami of adjacent spinal nerves interconnect to form plexuses, allowing for distributed nerve supply to specific body areas. The cervical plexus, derived from the ventral rami of C1–C4, primarily innervates the neck muscles and skin of the neck, head, and upper shoulder.[28] The brachial plexus, formed by C5–T1, supplies the upper limbs and includes major branches such as the radial nerve (extensor muscles and posterior skin of the arm and forearm), median nerve (flexor muscles of the forearm and thenar eminence), and ulnar nerve (intrinsic hand muscles and medial forearm).[29] The lumbar plexus arises from L1–L4 ventral rami and innervates the lower abdominal wall, anterior thigh, and medial leg, giving rise to nerves like the femoral and obturator.[30] The sacral plexus, contributed by L4–S4, provides innervation to the pelvis, buttocks, perineum, and lower limbs, originating nerves such as the sciatic and pudendal.[31] The coccygeal plexus, a small network from Co1 and contributions from S4–S5, supplies the skin around the coccyx and perianal region.[32]Ganglia

Ganglia are discrete clusters of neuron cell bodies located outside the central nervous system, serving as key organizational units within the peripheral nervous system.[33] They house the somata of peripheral neurons, enabling the transmission and, in certain cases, modulation of neural signals between the central nervous system and peripheral tissues.[34] Unlike nuclei in the central nervous system, ganglia lack extensive synaptic integration in sensory types but facilitate relay functions in autonomic varieties.[35] Peripheral ganglia are broadly classified into sensory, autonomic, and enteric types, each with distinct roles in signal handling. Sensory ganglia primarily contain cell bodies of afferent neurons that convey sensory information from peripheral receptors to the central nervous system.[35] These include the dorsal root ganglia, paired swellings located adjacent to the spinal cord near the dorsal roots of spinal nerves, and the trigeminal ganglion associated with cranial nerve V, positioned in the middle cranial fossa within Meckel's cave.[35][36] The neurons in sensory ganglia are pseudounipolar, featuring a single axonal process that splits into a peripheral branch extending to sensory endings and a central branch projecting to the spinal cord or brainstem; notably, these ganglia lack synapses, serving solely as waystations for unprocessed sensory input.[34][36] Dorsal root ganglia, for example, are closely linked to spinal nerves, containing cell bodies for somatic and visceral sensory fibers.[35] Autonomic ganglia encompass those of the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions, where postganglionic neuron cell bodies receive preganglionic inputs to relay signals to visceral effectors.[7] Sympathetic ganglia form the paravertebral chain—a bilateral series of 22-23 interconnected masses running parallel to the vertebral column from the cervical to sacral regions—with examples including the superior, middle, and inferior cervical ganglia.[37] Prevertebral sympathetic ganglia, such as the celiac and superior mesenteric, lie anterior to the aorta in the abdomen.[7] Parasympathetic ganglia are typically terminal, situated close to or embedded within target organs; the ciliary ganglion, for instance, resides in the orbit posterior to the eye, between the optic nerve and lateral rectus muscle, to innervate intraocular structures.[38] Neurons in autonomic ganglia are multipolar, with multiple dendrites receiving cholinergic synapses from preganglionic fibers, allowing for signal relay without extensive central processing.[38][33] Enteric ganglia constitute the intrinsic nervous system of the gastrointestinal tract, embedded within the gut wall to coordinate local neural circuits.[39] They form two main plexuses: the myenteric plexus, located between the longitudinal and circular smooth muscle layers along the entire digestive tract, and the submucosal plexus, situated in the submucosal connective tissue primarily in the small and large intestines.[40] These ganglia contain multipolar neurons interconnected by nerve fibers, forming integrative networks capable of autonomous processing.[39] In all peripheral ganglia, the primary function is to provide a peripheral locus for neuron cell bodies, protecting them from central vulnerabilities while facilitating efficient axonal distribution.[34] Sensory ganglia emphasize passive conduction of afferent signals, whereas autonomic and enteric ganglia support local integration through synaptic relays, enabling decentralized control of peripheral targets.[33][39]Somatic nervous system

Structure

The somatic nervous system comprises two primary components: afferent (sensory) fibers that transmit signals from sensory receptors in the skin, muscles, and joints to the central nervous system (CNS), and efferent (motor) fibers that carry signals from the CNS to skeletal muscles via alpha motor neurons, enabling voluntary movement.[6][41] These afferent fibers originate from specialized receptors such as mechanoreceptors in the skin for touch and proprioceptors in muscles and joints for position sense, relaying information directly to the spinal cord or brainstem.[42] Efferent fibers, in contrast, are lower motor neurons whose cell bodies reside in the ventral horn of the spinal cord or cranial nerve nuclei, synapsing directly at neuromuscular junctions without intermediary structures.[41] The pathways of the somatic nervous system travel through the cranial and spinal nerves, providing direct innervation to peripheral targets. There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves (primarily the oculomotor (III), trochlear (IV), abducens (VI), trigeminal (V), facial (VII), accessory (XI), and hypoglossal (XII) for somatic motor functions)[43] that connect the brainstem to head and neck structures, while 31 pairs of spinal nerves emerge from the spinal cord to supply the rest of the body.[6] Unlike the autonomic nervous system, somatic efferent pathways lack intervening ganglia, allowing for rapid, voluntary control of skeletal muscles.[44] The somatic nervous system is organized somatotopically, with sensory and motor innervation segmented according to spinal cord levels, forming dermatomes and myotomes. Dermatomes represent specific areas of skin innervated by a single spinal nerve root, such as the C6 dermatome covering the thumb and lateral forearm, allowing clinicians to localize spinal lesions based on sensory deficits.[26] Myotomes, the motor counterparts, are groups of muscles supplied by one spinal nerve root, for example, the C5 myotome including the deltoid and biceps for shoulder and elbow flexion.[26] This segmental arrangement arises from embryonic development and ensures precise mapping of the body's periphery to CNS levels.[45] Nerve fibers in the somatic nervous system are classified by diameter, myelination, and conduction velocity, with types A-alpha and A-beta being prominent. A-alpha fibers, with diameters of 12-20 μm and heavy myelination, conduct at 70-120 m/s and primarily serve motor functions to skeletal muscle or proprioception via muscle spindles.[46][47] A-beta fibers, smaller at 5-12 μm with moderate myelination, transmit touch and pressure sensations at 30-70 m/s from cutaneous mechanoreceptors.[46][47] These classifications, based on Erlanger-Gasser grouping, highlight how fiber properties optimize signal speed for somatic functions.[46]| Fiber Type | Diameter (μm) | Conduction Velocity (m/s) | Myelination | Primary Function in Somatic System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-alpha | 12-20 | 70-120 | Heavy | Motor to skeletal muscle; proprioception |

| A-beta | 5-12 | 30-70 | Moderate | Touch and pressure from skin |