Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

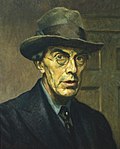

Roger Fry

View on Wikipedia

Roger Eliot Fry (14 December 1866 – 9 September 1934) was an English painter and critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent developments in French painting, to which he gave the name Post-Impressionism. He was an early figure to raise public awareness of modern art in Britain, and he emphasised the formal properties of paintings over the "associated ideas" conjured in the viewer by their representational content. He was described by the art historian Kenneth Clark as "incomparably the greatest influence on taste since Ruskin ... In so far as taste can be changed by one man, it was changed by Roger Fry".[2] The taste Fry influenced was primarily that of the Anglophone world, and his success lay largely in alerting an educated public to a compelling version of recent artistic developments of the Parisian avant-garde.[3]

Key Information

Life

[edit]Born in London in 1866, the son of the judge Edward Fry, he grew up in a wealthy Quaker family in Highgate. His siblings included Joan Mary Fry, Agnes Fry and Margery Fry; Margery was principal of Somerville College, Oxford. Fry was educated at Clifton College[4] and King's College, Cambridge,[5] where he was a member of the Conversazione Society, alongside freethinking men who would shape the foundation of his interest in the arts, including John McTaggart and Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson. After taking a first in the Natural Science tripos, he went to Paris and then Italy to study art. Eventually, he specialised in landscape painting.

In 1896, he married artist Helen Coombe and they had two children, Pamela and Julian. Helen became seriously mentally ill and the couple moved to Guildford, Surrey in the hope the quieter environment would help.[citation needed] But in 1910 Helen was committed to a mental institution, where she remained for the rest of her life. Fry took over care of their children with the help of his sister, Joan Fry. That same year, Fry met the artists Vanessa Bell and her husband Clive Bell, and it was through them that he was introduced to the Bloomsbury Group. Vanessa's sister, the author Virginia Woolf later wrote in her biography of Fry that "He had more knowledge and experience than the rest of us put together".

Shortly after their relocation to Guildford, Fry had a house called Durbins built to his own design in Chantry View Road, then on the edge of the town, overlooking the Surrey Hills. Durbins was in a stripped-back classical style with large windows suggesting Dutch precedent and Fry regarded it as a 'genuine and honest piece of domestic architecture'.[6] The most unusual feature is a double-height living hall (or ‘house-place’ as Fry called it). It is now a Grade II* listed building. He employed Lottie Hope and Nellie Boxall (in 1912) as his young servants until 1916 when he decided to rent the house and establish a trust for it. Lottie and Nellie went to work for Leonard and Virginia Woolf on his recommendation.[7]

In 1911 Fry began an affair with Vanessa Bell, who was recovering from a miscarriage. Fry offered her the tenderness and care she felt lacking from her husband. They remained lifelong close friends, even though Fry's heart was broken in 1913 when Vanessa fell in love with Duncan Grant and decided to live permanently with him.

After short affairs with artists Nina Hamnett and Josette Coatmellec, Fry too found happiness with Helen Maitland Anrep. She became his emotional anchor for the rest of his life, although they never married (she too had had an unhappy first marriage, to the mosaicist Boris Anrep).

Fry died after a fall at his home in London and his death caused great sorrow among the Bloomsbury Group, who loved him for his generosity and warmth. Vanessa Bell decorated his coffin. Fry's ashes were placed in the vault of Kings College Chapel in Cambridge. Virginia Woolf was entrusted with writing his biography, a task she found difficult because his family asked her to omit certain matters, his love affair with Vanessa Bell among them.[8]

Artistic style

[edit]

As a painter Fry was experimental (his work included a few abstracts), but his best pictures were straightforward naturalistic portraits,[9][10] although he did not pretend to be a professional portrait painter.[11] In his art he explored his own sensations and gradually his own personal visions and attitudes asserted themselves.[12] His work was considered to give pleasure, 'communicating the delight of unexpected beauty and which tempers the spectator's sense to a keener consciousness of its presence'.[13] Fry did not consider himself a great artist, "only a serious artist with some sensibility and taste".[14] He considered Cowdray Park his best painting: "the best thing, in a way that I have done, the most complete at any rate".[15]

Career

[edit]In the 1900s, Fry started to teach art history at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London.

In 1903 Fry was involved in the foundation of The Burlington Magazine, the first scholarly periodical dedicated to art history in Britain. Fry was its co-editor between 1909 and 1919 (first with Lionel Cust, then with Cust and More Adey) but his influence on it continued until his death: Fry was on the consultative committee of The Burlington since its beginnings and when he left the editorship, following a dispute with Cust and Adey regarding the editorial policy on modern art, he was able to use his influence on the committee to choose the successor he considered appropriate, Robert Rattray Tatlock.[16] Fry wrote for The Burlington from 1903 until his death: he published over two hundred pieces on eclectic subjects – from children's drawings to bushman art. From the pages of The Burlington, it is also possible to follow Fry's growing interest in Post-Impressionism.

Fry's later reputation as a critic rested upon essays he wrote on Post-Impressionist painters,[17] and his most important theoretical statement is considered to be An essay in Aesthetics,[18] one of a selection of Fry's writings on art extending over a period of twenty years published in 1920.[19] In "An essay in Aesthetics", Fry argues that the response felt from examining art comes from the form of an artwork; meaning that it is the use of line, mass, colour and overall design that invokes an emotional response. His greatest gift was the ability to perceive the elements that give an artist his significance.[20] Fry was also a born letter writer, able to communicate his observations on art or human beings to his friends and family.[21]

In 1906 Fry was appointed Curator of Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This was also the year in which he "discovered" the art of Paul Cézanne, the year the artist died, beginning the shift in his scholarly interests away from the Italian Old Masters and towards modern French art.

In November 1910, Fry organised the exhibition 'Manet and the Post-Impressionists' (post-impressionism being a term which Fry coined[22]) at the Grafton Galleries, London. This exhibition was the first to prominently feature Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse, and Van Gogh in England and brought their art to the public.[23] Though the exhibition would eventually be widely celebrated, the sentiments at the time were much less favourable. This was due to the exhibition's selection of art that the public was unaccustomed to at the time. Fry was not immune to the backlash. Desmond MacCarthy, the secretary of the exhibition stated that "by introducing the works of Cézanne, Matisse, Seurat, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Picasso to the British public, he smashed for a long time his reputation as an art critic. Kind people called him mad and reminded others that his wife was in an asylum. The majority declared him to be a subverter of morals and art, and a blatant self-advertiser." Yet the foreignness of "post-impressionism" would inevitably disappear and eventually, the exhibition would be regarded as a critical moment for art and culture.[24] Virginia Woolf later said, "On or about December 1910 human character changed", referring to the effect this exhibit had on the world. Fry followed it up with the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912. It was patronised by Lady Ottoline Morrell, with whom Fry had a fleeting romantic attachment.

In 1913 he founded the Omega Workshops, a design workshop based in London's Fitzroy Square, whose members included Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant and other artists of the Bloomsbury Group. It was an experimental design collective in which all the work was anonymous with everything that was produced in the workshops, bold decorative homeware ranging from rugs to ceramics and furniture to clothing, bearing only the Greek letter Ω (Omega). As Fry told a journalist in 1913: 'It is time that the spirit of fun was introduced into furniture and into fabrics. We have suffered too long from the dull and the stupidly serious.'[25] As well as high society figures such as Lady Ottoline Morrell and Maud Cunard, other clients included Virginia Woolf, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, W.B. Yeats and E.M. Forster and also Gertrude Stein, with whom Fry shared a love of contemporary art, on one of her visits to London in the 1910s.[25] The workshops also brought together the artists Wyndham Lewis, Frederick Etchells, Edward Wadsworth and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska who would later, following a quarrel between Fry and Wyndham Lewis with the latter setting up The Rebel Art Centre in 1914 as a rival business,[26] branch away to form the Vorticist movement. The workshops stayed open during World War I but closed in 1919. The Courtauld Gallery houses one of the most important collections of designs and decorative objects made by artists of the Omega Workshops[27] and, in 2017, held an exhibition 'Bloomsbury Art and Design' that presented a wide-ranging selection of objects from its holdings, many of which were bequeathed to The Courtauld Institute of Art by Roger Fry.[28] An earlier exhibition in 2009, 'Beyond Bloomsbury: Designs of the Omega Workshops 1913–19', contained the largest collection of surviving working drawings of the Omega Workshops, bequeathed to The Courtauld Gallery by Fry's daughter Pamela Diamand in 1958.[29]

The London Artists' Association was set up in 1925 by Samuel Courtauld and John Maynard Keynes at the instigation of Roger Fry[30] who was a friend of both men and advised them on their art collections.[31][32] Fry's association with Samuel Courtauld was celebrated by him in The Burlington Magazine after Courtauld endowed a chair in History of Art at London University which Fry welcomed as an 'unexpected realisation of a long-cherished hope'.[33] In 1933, he was appointed the Slade Professor at Cambridge, a position that Fry had much desired.

In September 1926 Fry wrote a definitive essay on Seurat in The Dial.[34] Fry also spent ten years translating, "for his own pleasure",[35] the poems of the symbolist poet Stephane Mallarmé.[36] Between 1929 and 1934, the BBC released a series of twelve broadcasts wherein Fry conveys his belief that art appreciation should begin with a sensibility to form as opposed to an inclination to praise art of high culture. Fry also argues that an African sculpture or a Chinese vase is just as deserving of study as a Greek sculpture.

His works can be seen in Tate Britain, the Ashmolean Museum, Leeds Art Gallery, National Portrait Gallery, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Manchester Art Gallery, Somerville College, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and the Courtauld Gallery who purchased the 1928 self-portrait (above) with the assistance of the Art Fund[37] and others in 1994.[38] The Collection of Roger Fry of paintings and decorative art objects bequeathed to the Courtauld [39][40] also contains photographs which are held in the Conway Library who are in the process of digitising their collection of primarily architectural images as part of the wider Courtauld Connects project.[41] Lithographs produced by Fry from 1927 to 1930 are held at Tate Britain and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.[42] The lithographs were drawn in France (except for one from Trinity College, Cambridge) and many were published in the portfolio, Ten Architectural Lithographs.[42]

The Arts Council exhibition 'Roger Fry Paintings and Drawings' at their St James Square gallery in 1952, consolidated Fry's reputation as an artist. A blue plaque was unveiled in Fitzroy Square on 20 May 2010.[23]

Gallery

[edit]-

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (1893)

-

Edith Sitwell (1915)

-

Virginia Woolf (1917)

-

Edith Sitwell (1918)

-

The Breakfast Table (c.1918)

-

Self portrait (1928)

-

Roger Fry (1930–1934)

Works

[edit]- Giovanni Bellini (1899)

- Studland Beach (1911)[43]

- Vision and Design (1920)

- Twelve Original Woodcuts (1921) – portfolio hand printed by Leonard & Virginia Woolf, the second publication of the Hogarth Press

- Duncan Grant (1923)

- A Sampler of Castille (1923)

- The Artist and Psycho-Analysis (1924)

- Art and Commerce (1926)

- Transformations (1926)

- Flemish Art (1927)

- Cézanne- A Study of His Development (1927) [First published in French as « Le développement de Cézanne », 1926]

- Henri Matisse (1930)

- Characteristics of French Art (1932)

- Arts of Painting and Sculpture (1932)

- Art History as an Academic Study (1933)

- Last Lectures (1933)

- Reflections on British Painting (1934)

Translations:

- Some poems of Mallarme (1936)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Search Results for England & Wales Births 1837–2006 – findmypast.co.uk". search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ Chilvers. Ian, "Fry, Roger." Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford, 1990, ISBN 9780199532940

- ^ Reed, Christopher, Introduction,' A Roger Fry Reader' University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1996 ISBN 978-0226266428

- ^ "Clifton College Register" Muirhead, J.A.O. p. 95: Bristol; J. W. Arrowsmith for Old Cliftonian Society; April 1948

- ^ "Fry, Roger (FRY885RE)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Durbins, including the summerhouse, Non Civil Parish". Historic England. 20 June 2024. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B.; Goldman, L., eds. (23 September 2004). "Nellie Boxall". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/94651. Retrieved 9 June 2023. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Woolf, Virginia, Roger Fry: A Biography, New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company; London: The Hogarth Press, 1940.

- ^ Chilvers, Ian, Dictionary of Art and Artists, Oxford University Press, 1990 ISBN 9780199532940

- ^ Portrait of Edward Carpenter, National Portrait Gallery, London

- ^ Letter to Lady Fry,22 January 1928

- ^ Technical Appreciation by an artist, Roger Fry, A Biography by Virginia Woolf, Harcourt, Brace and Co, New York, 1940

- ^ Earp T. W., critic of New Statesman – Retrospective Exhibition, Cooling Galleries, London, February 1931

- ^ Letter to Marie Mauron 20 June 1920

- ^ Letter to R. C. Trevelyan, 20 November 1903

- ^ Sutton (ed.), Letters of Roger Fry (1972) pp. 448, 452

- ^ Blunt, Anthony, Introduction Seurat, Phaidon Press, London, September 1965

- ^ Bullen, J. B., Introduction Vision and Design by Roger Fry, Dover Paperbacks, 1998 ISBN 9780486400877

- ^ Fry, Roger Preface to Vision and design Chatto and Windus, London, 1920

- ^ Sutton, Denys, Introduction Letters of Roger Fry Chatto and Windus, London, 1972 ISBN 0701115998

- ^ Sutton Denys, Preface to Letters of Roger Fry, Chatto and Windus, London 1972 ISBN 0701115998

- ^ Tate. "Post-impressionism – Art Term". Tate. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Roger Fry | Artist | Blue Plaques". English Heritage. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ MacCarthy, Desmond, "Desmond MacCarthy: The Post-Impressionist Exhibition of 1910", The Bloomsbury Group: A Collection of Memoirs and Commentary, University of Toronto Press, 1995; Print. Rev ed.

- ^ a b "Beyond Bloomsbury: Designs of the Omega Workshops 1913–19". courtauld.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Tate. "Rebel Art Centre – Art Term". Tate. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "The 20th Century". The Courtauld Institute of Art. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Bloomsbury Art & Design". The Courtauld Institute of Art. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Beyond Bloomsbury: Designs of the Omega Workshops 1913–19". courtauld.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "London Artists' Association | Artist Biographies". www.artbiogs.co.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Courtauld History". courtauld.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Collecting for Cambridge | The Fitzwilliam Museum". www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "The Warburg and Courtauld Institutes". The Burlington Magazine. 132 (1048 July 1990).

- ^ Seurat, Phaidon Press, London, 1965

- ^ Letter to Marie Mauron 12 November 1920

- ^ Sutton, Denys, Biographical Notes, Letters of Roger Fry, Chatto and Windus, London 1972.

- ^ "Self-Portrait by Roger Fry". Art Fund. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "A&A | Self-Portrait". www.artandarchitecture.org.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "The Courtauld Collection" (PDF).

- ^ "Courtauld Institute Galleries | museum, London, United Kingdom". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Who made the Conway Library?". Digital Media. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b Richard Howells (2020). "Roger Fry, Bloomsbury and transfer lithography". Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. 31. Te Papa: 5–18. ISSN 1173-4337. Wikidata Q106839642.

- ^ "Studland Beach by Roger Eliot Fry: Buy fine art print".

Sources

[edit]- Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry: A Biography (1940) ISBN 0-15-678520-X

- Denys Sutton, Letters of Roger Fry (1972) ISBN 0-7011-1599-8

- Frances Spalding, Roger Fry: Art and Life, University of California Press, (1980) ISBN 0-520-04126-7

- David Boyd Haycock. "A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War" (2009)

- Christopher Reed, A Roger Fry Reader (1996) ISBN 0-226-26642-7

- Gal, Michalle. Aestheticism: Deep Formalism and the Emergence of Modernist Aesthetics. Peter Lang AG International Academic Publishers, 2015 ISBN 978-3-0351-9992-5

External links

[edit]- 112 artworks by or after Roger Fry at the Art UK site

- Roger Fry at artcyclopedia.com

- Roger Fry at Oxford Encyclopedia of Aesthetics (2nd edition)

- Roger Fry' s biography in the Burlington Magazine

- Roger Fry – Vision and design, Chatto and Windus, London 1920

- "Post-Impressionism", Roger Fry's lecture on the closing of the "Manet and the Post-Impressionists" exhibition at the Grafton Galleries, as published in The Fortnightly Review

- "Roger Fry, Walter Sickert and Post-Impressionism at the Grafton Galleries", a reflection by Prof. Marnin Young on the 1910–1911 exhibition