Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

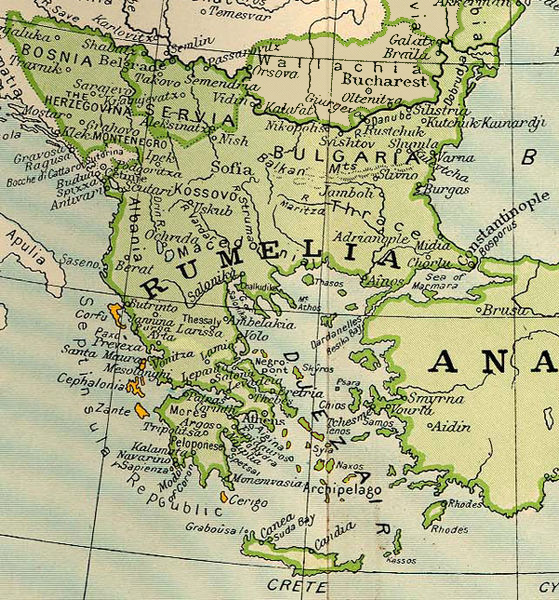

Rumelia

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Rumelia (Ottoman Turkish: روم ايلى, romanized: Rum İli, lit. 'Land of the Romans';[a] Turkish: Rumeli; Greek: Ρωμυλία) was a historical region in Southeastern Europe that was administered by the Ottoman Empire, roughly corresponding to the Balkans. In its wider sense, it was used to refer to all Ottoman possessions and vassals in Europe. These would later be geopolitically classified as "the Balkans", although Hungary and Moldova are sometimes excluded.[1][2] In contemporary English sources, Rumelia was known as Turkey in Europe.

Etymology

[edit]

In this context, Rûm means “Romans” and ėli means “land”, hence Rumelia (Ottoman Turkish: روم ايلى, Rūm-ėli; Turkish: Rumeli) literally “Land of the Romans” in Ottoman Turkish. The term referred to territories of the Ottoman Empire in Europe that had formerly belonged to the Byzantine Empire (the empire known to its own rulers and subjects as the Roman Empire), whose citizens styled themselves Rhomaioi (“Romans”). Although Greek became the predominant administrative and liturgical language, the empire was multiethnic and its Roman identity was civic and imperial rather than purely linguistic or ethnic.

In medieval Islamic and Ottoman usage, Rûm denoted the lands and peoples of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople, not the medieval Latin West. The Seljuks called Anatolia “the land of Rûm” after its gradual conquest from Byzantium following the Battle of Manzikert (1071). Their Anatolian polity was known to contemporaries as the Sultanate of Rum, meaning a sultanate established in the lands of the Romans; it was centred in central Anatolia until the defeat at the Battle of Köse Dağ (1243), after which it fragmented into the Anatolian beyliks.

With the Ottoman expansion across Anatolia and into the Balkans, and especially after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Rumeli came to apply primarily to the empire’s European provinces in the Balkans. The region remained largely Christian for centuries, while processes of Islamisation affected some populations, including Albanians, Bosniaks and certain communities among Greeks, Serbs, Bulgarians and Vlachs.

The term “Roman” for the Byzantine polity also appears in Western sources. Latin documents, including those from Genoa, frequently used Romania as a name for the Byzantine Empire during the Middle Ages.[3]

The name survives in several Balkan languages: Albanian: Rumelia; Bulgarian: Румелия, Rumeliya; Greek: Ρωμυλία, Romylía, and Greek: Ρούμελη, Roúmeli; Macedonian: Румелија, Rumelija; Serbo-Croatian: Румелија, Rumelija; and Romanian: Rumelia. Many grand viziers, viziers, pashas and beylerbeyis were of Rumelian origin.

Geography

[edit]

Rumelia comprised the Ottoman lands in the Balkans, notably Thrace, Macedonia and much of Moesia—covering most of present-day Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Western Thrace in Greece, and the Turkish part of Eastern Thrace. It was bounded to the north by the Sava and Danube, to the west by the Adriatic, and to the south by the Morea. The beylerbey’s seat was first at Plovdiv (Filibe) and later at Sofia.[4] The name "Rumelia" was ultimately applied to a province composed of central Albania and northwestern Macedonia, with Bitola being the main town.

Following the administrative reorganization made by the Ottoman government between 1870 and 1875, the name Rumelia ceased to correspond to any political division. Eastern Rumelia was constituted as an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of Berlin (1878),[4] but on September 6, 1885, after a bloodless revolution, it was united with Bulgaria.[5] The Kosovo Vilayet was created in 1877.[6]

In Turkey, the word Trakya (Thrace) has now mostly replaced Rumeli (Rumelia) to refer to the part of Turkey that is in Europe (the provinces of Edirne, Kırklareli, Tekirdağ, the northern part of Çanakkale Province and the western part of Istanbul Province). However, "Rumelia" remains in use in historical contexts and is still used in the context of the culture of the current Turkish populations of the Balkans and the descendants of Turkish immigrants from the Balkans. The region in Turkey is also referred to as Eastern Thrace, or Turkish Thrace. In Greece, the term Ρούμελη (Rumeli) has been used since Ottoman times to refer to Central Greece, especially when it is juxtaposed with the Peloponnese or Morea. The word Rumeli is also used in some cases, mostly in Istanbul, to refer exclusively to the part of Istanbul Province that is west of the Bosphorus strait.

See also

[edit]- Ada Kaleh

- Millet (Ottoman Empire)

- Ottoman Albania

- Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Ottoman Bulgaria

- Ottoman Croatia

- Ottoman Greece

- Ottoman Hungary

- Ottoman Kosovo

- Ottoman Moldova

- Ottoman Romania

- Ottoman Serbia

- Ottoman Vardar Macedonia

- Ottoman wars in Europe

- Rum Millet

- Rumelia Eyalet

- Sultanate of Rum

- Turks in the Balkans

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ At the time meaning Eastern Orthodox Christians and more specifically Christians from the Byzantine rite

Citations

[edit]- ^ Graubard, Stephen Richards, ed. (1999). A new Europe for the old?. New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.: Transaction Publishers. pp. 70–73. ISBN 978-0-7658-0465-5.

- ^ Juhász, József (2015). "Hungary and the Balkans in the 20th Century — From the Hungarian Perspective". Prague Papers on the History of International Relations: 115 – via CEJSH.

Many Western observers held Hungary to be one of the nations of the Balkans. But Hungary never regarded itself as part of that region, especially since the term 'Balkans' carried negative connotations.

- ^ Fossier, Robert; Sondheimer, Janet (1997). [[1](https://archive.org/details/cambridgeillustr00robe) The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages]. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26644-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b Reclus, Onésime; Ibáñez, Vicente Blasco; Reclus, Élisée; Doré, Gustave (1907). Novísima Geografía Universal (in Spanish). Madrid La Edit. Española-Americana. p. 636. OCLC 432767489.

- ^ Frucht, Richard (2004). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 807. ISBN 1576078000.

- ^ Verena Knaus; Gail Warrander (2010). Kosovo. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 11. ISBN 978-1841623313.

General and cited references

[edit]- Bronza, Boro (2010). "The Habsburg Monarchy and the Projects for Division of the Ottoman Balkans, 1771–1788". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe Between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 51–62. ISBN 9783643106117.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). 1911.

Rumelia

View on GrokipediaRumelia (Ottoman Turkish: روم ايلى, Rūm-ili, meaning "Land of the Romans") was the Ottoman Empire's term for its territories in southeastern Europe, encompassing much of the Balkan Peninsula conquered from the Byzantine Empire and successor states.[1][2] The region, administered initially as the Eyalet of Rumelia from the late 14th century, formed the core of Ottoman power in Europe, serving as a vital military recruitment ground, economic hub, and strategic buffer against external threats.[3] For much of its existence until the 19th-century administrative reforms and nationalist revolts, it remained the empire's largest province, centered around key cities like Edirne, Sofia, and Monastir, and played a pivotal role in sustaining Ottoman imperial expansion and governance.[4]

Name and Terminology

Etymology

The term Rumelia derives from Ottoman Turkish Rûm-îlî (روم ایلی), literally meaning "land of the Rûm". In Ottoman and broader Islamic nomenclature, Rûm (روم) designated the Romans, particularly the Byzantines and their Orthodox Christian subjects, as the Eastern Roman Empire was regarded as the successor to classical Rome following its fall in 476 CE.[5] The suffix îlî or eli, from Turkic il meaning "land", "country", or "domain", denoted territorial possession or administrative region.[6] This etymology reflects the Ottoman perspective on their Balkan conquests as territories formerly held by Roman/Byzantine authority, rather than a direct ethnic reference to Greeks, despite occasional loose translations as "land of the Greeks" in some European renditions.[5] The name emerged in Ottoman administrative usage during the 14th and 15th centuries, coinciding with the empire's expansion into southeastern Europe after initial incursions in the 1360s, such as the capture of Adrianople (Edirne) in 1361.[5] By the reign of Mehmed II (r. 1451–1481), Rumeli had solidified as the designation for the core European provinces, distinguishing them from Anatolian holdings often termed Anadolu. Early Ottoman chronicles, like those of Aşıkpaşazade (fl. late 15th century), employed variants such as Rum ili to describe these domains, underscoring their origin in subjugating Byzantine-held lands.[7] Over time, European languages adapted it as Rumelia or Roumelia, retaining the connotation of Roman heritage without implying political continuity with Rome.Historical Usage and Variations

The term Rumelia was employed by Ottoman authorities from the mid-14th century onward to designate territories in Europe acquired through conquests from the Byzantine Empire, encompassing regions such as Thrace, Macedonia, and parts of Bulgaria.[8] This usage reflected a broad geographical conception of Ottoman holdings west of the Bosporus, often contrasted with Anatolia, and initially lacked strict administrative boundaries, serving instead as a collective reference to Balkan domains under central control.[9] By the late 14th century, during the reign of Sultan Murad I (1362–1389), Rumelia evolved into a formalized administrative entity known as the Rumelia Eyalet (Rumeli Eyaleti), the empire's largest and most strategically vital province, governed from Sofia until its relocation to Edirne around 1520. This eyalet comprised dozens of sanjaks, including those centered on key cities like Thessaloniki, Monastir, and Üsküb (Skopje), and functioned as the core of Ottoman military recruitment and taxation in Europe through the 18th century.[10] Its scope covered approximately the modern territories of Bulgaria, Greece, Albania, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro, and parts of Serbia and Romania, adapting over time to territorial losses from wars with Habsburgs and Russia.[11] In the 19th century, amid the Tanzimat reforms of 1839–1876, the Rumelia Eyalet underwent significant restructuring, dissolving into smaller vilayets such as the Danube Vilayet (established 1864, spanning northern Bulgaria and parts of Romania) and the Salonica Vilayet, to enhance centralized oversight and address rising ethnic nationalisms. A notable variation emerged with Eastern Rumelia, an autonomous Ottoman province delineated by the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, covering southern Bulgaria (about 36,000 square kilometers) with Plovdiv as its capital, intended as a buffer against Russian influence but annexed by the Principality of Bulgaria in 1885 following a bloodless coup. This period marked a contraction of the term's application, increasingly limited to residual Ottoman Balkan holdings amid partitions like those after the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War, while "Rumeli" persisted in Turkish as a shorthand for the European provinces collectively.[12]Geography

Physical Landscape

Rumelia encompassed a diverse array of physical features typical of the Balkan Peninsula, dominated by rugged mountainous terrain interspersed with river valleys, basins, and limited coastal plains. The region included three primary mountain systems: the Dinaric Alps along the western Adriatic-facing areas, the Pindus range in the southern extremities, and the Balkan Mountains (Stara Planina) traversing the central-eastern portions, which created natural barriers and influenced settlement patterns.[13][14] Karst landscapes, characterized by deep gorges, caves, and poljes (flat karst fields), were prevalent, particularly in the Dinaric regions, resulting from limestone dissolution over millennia.[15] Major rivers shaped the hydrology and accessibility, with the Danube and its tributary the Sava delineating the northern boundary, draining northward into the Black Sea and supporting fertile alluvial plains in lower reaches.[16] Inland, eastward-flowing systems like the Morava, Vardar, Struma, Mesta, and Maritsa provided drainage toward the Aegean, often carving narrow valleys through highlands that facilitated trade routes but hindered large-scale agriculture due to steep gradients and modest precipitation in lowlands.[13][16] Climatic conditions varied latitudinally and altitudinally, with interior highlands and northern areas experiencing a continental regime of cold, snowy winters (average temperatures below 0°C) and warm summers (up to 25°C), accompanied by annual rainfall of 600-1,000 mm concentrated in spring and autumn.[15] Coastal zones in the south and west transitioned to Mediterranean influences, featuring milder winters, drier summers, and higher evaporation rates, while eastern Black Sea margins saw more maritime moderation with increased humidity.[17] These variations supported diverse vegetation, from alpine meadows above 2,000 meters to deciduous forests and scrub in lower elevations, though deforestation from Ottoman-era timber use for shipbuilding and fuel intensified erosion in steeper terrains.[15]Territorial Extent and Changes

The Rumelia Eyalet, formed as the Ottoman Empire's core European province following conquests beginning with Gallipoli in 1354, initially encompassed Thrace, Macedonia, and adjacent regions up to the Danube River by the late 14th century.[18] Its territory expanded significantly during the 15th and 16th centuries through campaigns under sultans Mehmed II and Selim I, incorporating Bosnia in 1463, Herzegovina, and Serbia, while reaching approximate boundaries from the Adriatic Sea in the west to the Black Sea in the east, and from the Danube in the north to the Aegean in the south.[19] By 1609, administrative records depicted Rumelia as including multiple sanjaks across the Balkans, excluding detached eyalets like Bosnia formed in 1580..png) Administrative restructuring in the 19th century marked significant changes to Rumelia's extent under the Tanzimat reforms. In 1836, the expansive Rumelia Eyalet was partitioned into three smaller eyalets: Salonica (Thessaloniki), Edirne (Adrianople), and Monastir (Bitola), reflecting efforts to improve governance amid growing provincial autonomy demands.[4] The Vilayet Law of 1864 further transformed the system, replacing remaining eyalets with vilayets; Rumelia's remnants were reorganized into entities like the Danube Vilayet in 1867, which spanned northern Bulgaria and Dobruja.[20] Territorial contractions accelerated due to nationalist revolts and European interventions. Greece gained independence in 1830, detaching the Peloponnese, central Greece, and Thessaly from Ottoman control; Serbia achieved de facto autonomy in 1830 and full independence by 1878.[18] The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 resulted in massive losses, with the Treaty of San Stefano (revised at Berlin) creating the Principality of Bulgaria from northern Rumelia, while the autonomous Province of Eastern Rumelia was established south of the Balkans, covering modern southern Bulgaria excluding the Rhodope Mountains. This province persisted until its unification with Bulgaria in 1885, despite Ottoman nominal suzerainty until 1908.[21] The Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 finalized Rumelia's dissolution, as Ottoman forces were expelled from nearly all remaining European territories, including Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia, leaving only Eastern Thrace under control until the Balkan Pact of 1913 and subsequent Greco-Turkish War.[18] By 1913, Rumelia as an Ottoman administrative concept had ceased to exist beyond Istanbul's environs.[22]Ottoman Administration

Early Eyālets and Governance

The Ottoman conquests in the Balkans from the mid-14th century onward established Rumelia as the primary European territorial domain, initially administered through a system of military fiefs called timars. These were granted to sipahi cavalry officers, who held revenue rights in exchange for providing armed service, forming the backbone of provincial military mobilization and fiscal extraction. Local elites, particularly Christian notables who converted to Islam, were incorporated into this structure, receiving land grants or administrative roles to ensure loyalty and facilitate governance amid diverse populations.[23] By the late 14th century, during the reign of Sultan Murad I (r. 1362–1389), the expanding territories were centralized under a beylerbey (governor-general) of Rumelia, tasked with overarching civil, military, and fiscal oversight of the European provinces up to the Danube. This beylerbeylik of Rumelia functioned as the empire's premier European command, with the beylerbey second only to the grand vizier in authority, leading campaigns, maintaining order, and remitting taxes to the sultan. Subdivisions emerged as sanjaks, each governed by a sanjakbey responsible for local defense, tax collection via the timar system, and judicial functions under Islamic law, though non-Muslim communities retained customary autonomy through village headmen.[24] Governance emphasized military efficiency, with Rumelia serving as a recruitment reservoir for the devşirme levy of Christian youths trained for elite Janissary corps and administrative posts, bolstering central control. The beylerbey's court in Edirne (Adrianople) handled appeals, provincial defters (registers) tracked timar allocations and revenues, and periodic tahrir surveys updated fiscal data to prevent corruption. This structure persisted into the 15th and early 16th centuries, adapting to conquests like those after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, which integrated Thrace more firmly without immediate major restructuring.[23] The formalization of eyalets as standardized provinces occurred gradually by the late 16th century, with Rumelia redesignated as the Eyalet of Rumelia around 1591, though its core beylerbeylik framework endured. Early eyalets within or carved from Rumelia included nascent units like those in Bulgaria and Albania, subdivided into sanjaks such as Vidin, Nikopol, and Ohrid, each with kazas (districts) for granular administration. Authority balanced central kanun (sultanic law) with local örf customs, prioritizing stability and revenue over ethnic uniformity, as evidenced by the integration of timariot forces numbering tens of thousands by 1500.[24]19th-Century Reforms and Vilayets

The Tanzimat reforms, initiated in 1839 and extending through 1876, aimed to centralize Ottoman governance, curb provincial autonomy, and integrate European administrative practices to bolster state efficiency and revenue collection in regions like Rumelia, where decentralized eyalets had fostered corruption and local power abuses.[25] In Rumelia, these efforts began with the subdivision of the vast Rumelia Eyalet into smaller eyalets during the 1840s and 1850s, including the creation of the Selanik Eyalet in 1846, Yanya Eyalet around 1850, and others like Üsküb, to facilitate closer supervision amid rising Balkan unrest and fiscal demands.[20] The cornerstone of these reforms was the Vilayet Law (Teskil-i Vilayet Nizamnamesi) promulgated on January 21, 1864, which replaced the irregular eyalet system with standardized vilayets governed by centrally appointed valis (governors) endowed with executive, judicial, and fiscal powers, overseen by provincial administrative councils that included elected Muslim and non-Muslim representatives to promote local participation without undermining sultanic authority.[20] This law emphasized hierarchical subdivisions—vilayets into sanjaks (districts), kazas (subdistricts), and nahiyes (townships)—with mechanisms for regular reporting to Istanbul, tax standardization via tithe farming reforms, and infrastructure improvements to enhance control over diverse populations.[26] Implementation in Rumelia commenced experimentally with the Danube Vilayet (Tuna Vilayeti) on May 20, 1864, covering sanjaks of Vidin, Nikopol, Rusçuk, Tulcea, and Sofia, totaling about 130,000 square kilometers and serving as a pilot for the vilayet model due to its strategic position and mixed demographics; it featured an elected general assembly of 120 members (60 Muslims, 60 non-Muslims) to advise on budgets and local affairs.[27] By 1867, the system expanded with the establishment of the Salonica Vilayet (encompassing Thessaloniki and surrounding areas) and Janina Vilayet (in Epirus), which absorbed remnants of the former Rumelia Eyalet, followed by Scutari Vilayet (1867, northern Albania) and Monastir Vilayet (1874, Macedonia).[28] These changes reduced the Rumelia Eyalet's direct remnants by 1867, integrating its territories into a framework designed to suppress banditry, streamline military recruitment, and counter nationalist stirrings through balanced representation, though persistent ethnic tensions limited full efficacy.[27] Further refinements occurred in the 1870s, including the Kosovo Vilayet's formation in 1876 from parts of Danube and other units, reflecting adjustments to post-1877-1878 war losses, with valis empowered to form mixed commissions for dispute resolution and development projects like roads and telegraphs to bind peripheral regions tighter to the core.[20] Despite these structural innovations, the reforms' success in Rumelia was uneven, as vilayet councils often favored urban elites and central edicts clashed with local customs, contributing to administrative overload amid accelerating autonomy movements by the 1880s.[26]Historical Development

Conquest and Consolidation (14th-15th Centuries)

The Ottoman penetration into the Balkans commenced in 1354 when forces under Sultan Orhan captured Gallipoli after an earthquake weakened Byzantine fortifications, providing a bridgehead for further incursions into Thrace.[29] Under Murad I (r. 1362–1389), expansion accelerated with the seizure of Adrianople (Edirne) around 1361–1363, which was refortified and designated the Ottoman capital, displacing Byzantine control in eastern Thrace.[30] Murad's victory at the Battle of Maritsa on September 26, 1371, routed a coalition of Bulgarian and Serbian forces numbering several thousand, enabling the occupation of key Macedonian towns such as Dráma and Serres, and imposing tribute on regional lords.[31] The Battle of Kosovo on June 15, 1389, against a Serbian-led alliance under Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović, resulted in heavy casualties on both sides—including the deaths of Murad and Lazar—but facilitated the piecemeal subjugation of Serbian territories through vassalage and raids, despite temporary setbacks from Hungarian interventions.[29] Bayezid I (r. 1389–1402), known as Yildirim for his rapid campaigns, intensified conquests by vassalizing the Bulgarian Tsardom in 1393 after capturing key fortresses like Vidin and Tirnova, integrating much of its territory into Ottoman domains while allowing Tsar Ivan Shishman nominal rule until his death in 1395.[29] Bayezid's sieges of Constantinople (1394–1402) strained Byzantine resources but were interrupted by Timur's invasion, culminating in the Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Ankara on July 20, 1402, which triggered a 11-year interregnum among rival princelings and briefly halted Balkan consolidation.[29] Mehmed I (r. 1413–1421) reasserted authority by defeating rivals and stabilizing Thrace and Macedonia, laying groundwork for renewed expansion. Mehmed II (r. 1444–1446, 1451–1481) achieved the pivotal conquest of Constantinople on May 29, 1453, after a 53-day siege deploying approximately 80,000 troops, massive artillery including urban cannons, and naval blockades against a defenders' force of about 7,000, ending the Byzantine Empire and securing Ottoman dominance over the Straits.[29] Subsequent campaigns completed the annexation of Serbia by 1459, following the fall of Smederevo, and incorporated Bosnia in 1463 after defeating King Stephen Thomas Kotromanić, with Albania resisting under Skanderbeg until his death in 1468.[29] Consolidation involved subdividing territories into sanjaks governed by appointed beys, such as those in Sofia and Niš established under Murad I, and the strategic appointment of Lala Şahin Pasha as beylerbeyi of Rumelia to oversee European provinces.[32] The timar system distributed land revenues to sipahi cavalry for military service, fostering loyalty and settlement of Turkic warriors, while initial tolerance of Christian autonomies transitioned to direct rule via garrisons and the nascent devşirme levy of Christian youths for Janissary corps, ensuring administrative integration amid ongoing revolts.[33]Zenith and Internal Dynamics (16th-18th Centuries)

The Rumelia Eyalet, as the primary administrative unit encompassing the Ottoman Balkans, attained its zenith in the 16th century under Sultan Suleiman I (r. 1520–1566), when centralized governance and military mobilization reached peak efficiency. Governed by the Beylerbey of Rumelia—a high-ranking official often drawn from the devshirme system and residing in Constantinople during peacetime—the eyalet comprised approximately 35–37 sanjaks, including key territories such as Salonika, Bosnia, and Belgrade. This structure generated substantial revenues, with the Beylerbey receiving an annual income of 260,000 ducats and authority over sanjak beys whose fiefs yielded 4,000–12,000 ducats each, supporting a provincial treasury that funded garrisons, taxes, and religious endowments.[34] The Beylerbey's dual role as civil administrator and military commander enabled rapid mobilization for European campaigns, underscoring Rumelia's strategic centrality in sustaining the empire's expansive ambitions.[34] The timar system formed the backbone of Rumelia's internal economic and martial dynamics, allocating state-owned lands as hereditary fiefs (timars under 20,000 aspers annually, ziamets from 20,000–100,000 aspers, and larger khasses for elites) to sipahi cavalrymen in exchange for equipped horsemen proportional to revenue—typically one per 3,000–6,000 aspers. By mid-century, this supported roughly 50,000 feudal sipahis in Rumelia, supplemented by timarji auxiliaries earning 10–40 ducats to provide horses and retainers, ensuring a disciplined force that formed the empire's main battle line.[34] Revenues derived from tithes, rents, and Christian poll-taxes (kharaj, yielding 1.6 million ducats empire-wide, with 25 aspers per head in Rumelia) were meticulously recorded by defter emins, while Suleiman's 1530 kanun reforms centralized fief assignments via imperial teskeres, limiting inheritance to qualified sons and curbing local abuses. Devshirme levies, drawing 3,000–12,000 Christian boys every four years primarily from Albanian and Slavic mountain regions, further integrated Balkan populations into Ottoman elites as janissaries (totaling ~12,000 disciplined infantry) after conversion and training, fostering loyalty amid multi-ethnic millets governed by personal laws under ulema oversight.[34] Irregular forces like akinjis (up to 60,000 mounted raiders exempt from taxation) augmented formal troops but introduced volatility, often plundering allied territories during expeditions. Judicial administration, led by the kaziasker of Rumelia appointing ~200 kazis and naibs, enforced sharia alongside kanuns for criminal and fiscal matters, maintaining order across diverse Christian subjects who held tapu usage rights but no fee-simple ownership.[34] By the 17th century, prolonged warfare eroded the timar framework, with fief fragmentation and sales to non-military holders reducing sipahi numbers and fiscal yields, as military technology shifts favored cash-paid infantry over feudal cavalry. In the 18th century, central authority weakened amid elite power struggles and provincial defiance, exemplified by the rise of ayan notables consolidating timar revenues and banditry networks in Rumelian mountains (e.g., 1785–1808 outbreaks requiring state militarization responses). The Rumeli vali (successor to the beylerbey) struggled against secessionist undercurrents and disaffection spanning ethnic lines, signaling de-legitimization of Ottoman control prior to 19th-century upheavals, though the eyalet persisted until mid-century restructurings detached sanjaks like those in the Peloponnese (24 total noted in 1609, reduced thereafter).[10][35]Decline, Nationalism, and Partition (19th Century)

The Ottoman Empire's authority in Rumelia deteriorated progressively during the 19th century, undermined by administrative inefficiencies, technological and military lags relative to European powers, and the diffusion of nationalist ideologies that eroded loyalty among Christian subjects. Early losses included the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830), which expelled Ottoman forces from the Peloponnese, continental Greece, and Aegean islands, culminating in the establishment of the independent Kingdom of Greece via the Treaty of Constantinople on July 21, 1832.[36] In parallel, Serbian principalities secured de facto autonomy after the First Uprising (1804–1813) and Second Uprising (1815), formalized by the Akkerman Convention in 1826 and the Hattişerif of 1830, granting hereditary rule to the Obrenović dynasty under nominal Ottoman suzerainty while excluding Ottoman garrisons from most territories.[37][38] Tanzimat reforms, proclaimed via the Gülhane Edict on November 3, 1839, and extended through the Islahat Fermanı of 1856, centralized taxation, conscription, and bureaucracy while promising equality across religious communities, but in Rumelia, these initiatives disrupted local power structures—such as the Phanariote privileges in the Danubian Principalities—and inadvertently amplified ethnic grievances by associating modernization with Ottoman cultural dominance rather than inclusive governance.[39] The 1864 Vilayet Law reorganized the sprawling Rumelia Eyalet into the Danube Vilayet (Tuna Vilayeti), encompassing sancaks like Sofia, Niš, Vidin, and Rusçuk, with a population exceeding 2 million, aiming to enhance surveillance and revenue extraction amid detected conspiracies, yet this consolidation exacerbated perceptions of overreach and failed to suppress clandestine nationalist networks.[40] Nationalist fervor, propagated through secret societies like the Filiki Eteria for Greeks and influenced by Pan-Slavic currents from Russia, manifested in recurrent insurrections that exposed the empire's reliance on irregular forces and inability to quell dissent without alienating European guarantors. The Herzegovina Uprising erupted in July 1875, spreading to Bulgarian districts and igniting the April Uprising on May 2, 1876 (Julian calendar; April 20 Old Style), centered in the Sredna Gora mountains and Plovdiv region of Rumelia, where rebels numbering around 30,000 seized arms depots before Ottoman regulars and bashi-bazouk militias—totaling over 50,000 troops—crushed the revolt within two weeks, resulting in an estimated 15,000–60,000 civilian deaths amid widespread village burnings and atrocities documented by foreign consuls.[41][42] These events, amplified by Pan-Slavic advocacy and Western reporting on the "Bulgarian Horrors," precipitated the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), wherein Russian forces advanced through Rumelia, capturing key fortresses like Plevna after sieges costing over 30,000 Ottoman casualties, and imposed the Treaty of San Stefano on March 3, 1878, which envisioned a vast Bulgarian autonomy encompassing much of Rumelia but was curtailed by the Congress of Berlin later that year.[43] This era's partitions fragmented Rumelia into semi-independent entities—Serbia expanded in 1833 to include territories up to the Sava River, the Danubian Principalities united as Romania in 1859—reflecting the causal primacy of ethno-linguistic mobilization over Ottoman reform efforts, as multi-confessional imperial structures proved untenable against self-determination demands rooted in 18th-century European precedents like the American and French revolutions.[44] By mid-century, Christian populations in Rumelia, comprising roughly 60% of the region's inhabitants per Ottoman censuses, increasingly prioritized confessional solidarity and territorial irredentism, hastening the devolution of direct control to local voyvodas and hospodars while Ottoman garrisons dwindled to symbolic presences.[45]Eastern Rumelia and Final Dissolution (1878-1913)

The Congress of Berlin, convened from June 13 to July 13, 1878, revised the Treaty of San Stefano and established Eastern Rumelia as an autonomous Ottoman province south of the Danube and Balkan Mountains, with Plovdiv as its capital.[46] This arrangement aimed to curb Russian influence in the Balkans by separating it from the newly autonomous Principality of Bulgaria, reflecting British and Austrian priorities to maintain Ottoman territorial integrity against Slavic nationalism.[47] The province's Organic Statute, drafted by a commission of Great Power representatives, provided for a mixed administrative council and a Christian governor-general nominated by the Ottoman Sultan with the assent of the powers for a five-year term.[48] Governance emphasized Christian participation, with Prince Alexander Bogoridi serving as the first governor-general from 1879 to 1884, followed by Gavrail Krăstevich until the unification.[47] [49] Despite nominal Ottoman suzerainty, local Bulgarian nationalists viewed Eastern Rumelia—predominantly ethnically Bulgarian—as artificially divided, fostering unrest through organizations like the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee.[50] On September 5, 1885, uprisings erupted in towns like Saedinenie (Goliamo Konare), prompting Rumelian militia under Major Danail Nikolaev to advance on Plovdiv.[50] The next day, September 6, they seized the capital without resistance, ousted Krăstevich's government, and proclaimed unification with the Principality of Bulgaria, an act Prince Alexander I endorsed despite initial hesitation.[50] [51] This bloodless coup triggered the Serbo-Bulgarian War (November 1885), but Bulgaria's victory at Slivnitsa led to de facto recognition by the Great Powers, formalized in the Tophane Agreement of April 5, 1886, under which Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II reluctantly confirmed Bulgarian administration while retaining nominal suzerainty.[52] Bulgaria's unification expanded its territory and population, but formal independence from Ottoman overlordship persisted until September 22, 1908, when Prince Ferdinand I declared the Principality a fully sovereign Kingdom of Bulgaria in Veliko Tarnovo, exploiting the Young Turk Revolution and Austria-Hungary's annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina.[53] This act ended Ottoman nominal authority over the unified Bulgarian lands, though irredentist claims on Macedonia fueled tensions. The final dissolution of Ottoman Rumelia occurred during the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, as the Balkan League—comprising Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro—declared war on October 8, 1912, to partition remaining Ottoman European territories, including Macedonia and Thrace.[54] Ottoman forces suffered defeats, losing key cities like Thessaloniki and Edirne; the Treaty of London, signed May 30, 1913, confined Ottoman holdings to Eastern Thrace east of the Enos-Midia line, effectively ending five centuries of control over Rumelian heartlands.[54] The subsequent Second Balkan War (June–August 1913) redistributed spoils among former allies but did not restore Ottoman gains in Rumelia, marking the irreversible fragmentation of these provinces into nascent Balkan nation-states.Demographics and Society

Population Composition Under Ottoman Rule

In the early phases of Ottoman rule following the conquest of the Balkans in the 14th and 15th centuries, Rumelia's population consisted primarily of indigenous Christian communities, including South Slavs (such as proto-Bulgarians, Serbs, and others), Greeks, Albanians, and Vlachs, with limited Turkish settlement concentrated in military garrisons and administrative centers. Ottoman tahrir surveys from the 15th to 17th centuries recorded predominantly non-Muslim reaya (taxpaying subjects), reflecting minimal initial Islamization outside urban elites and frontier zones.[55] By the 18th century, localized conversions had increased Muslim proportions in regions like Bosnia and Albania, where converted Slavs (Bosniaks) and Albanians formed distinct groups, alongside Turkish and Circassian migrants, though Christians remained the overall majority across Rumelia.[56] The 1831 Ottoman census, one of the earliest comprehensive counts, illustrated this imbalance in Rumelia province: Muslims numbered 513,448 (approximately 37%), while Greek Orthodox Christians totaled 811,546 (about 59%), with the remainder including smaller Catholic, Armenian, and Jewish communities; the total population was 1,369,766.[57] These figures, derived from male-only registrations for taxation, likely undercounted females and children but highlighted the millet-based categorization prioritizing religion over ethnicity, with the Rum Orthodox millet encompassing diverse groups like Bulgarians and Serbs under Phanariote Greek clergy. Jewish populations, though small (under 2% empire-wide), concentrated in cities like Thessaloniki and Edirne, benefiting from Ottoman protections post-1492 expulsions from Spain.[57] By the late 19th century, after Tanzimat reforms and amid nationalist upheavals, Muslim shares rose in many areas due to Anatolian refugee inflows, devşirme legacies, and voluntary conversions for socioeconomic advantages, though Christians predominated in rural eastern districts. The 1897 census for successor vilayets (Edirne, Selanik/Thessaloniki, Kosovo, and Manastır, core Rumelian territories) showed varied compositions, with corrections for undercounts of non-Muslims and females yielding the following approximate religious-ethnic breakdowns (Muslims primarily Turks, Albanians, and converts; non-Muslims including Greeks, Slavs, and Vlachs):| Vilayet | Total Population (Corrected) | Muslims (%) | Greeks (%) | Other Christians (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edirne | 1,220,053 | 55 | 8 | 37 (incl. Bulgarians, Armenians) |

| Selanik | 1,310,181 | 46 | 29 | 25 (incl. Bulgarians, Vlachs) |

| Kosovo | 1,416,290 | 81 | <1 | 18 (incl. Serbs, Armenians) |

| Manastır | 1,416,726 | 58 | 23 | 19 (incl. Albanians, Vlachs) |