Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Russian Compound

View on Wikipedia

The Russian Compound (Hebrew: מִגְרַשׁ הָרוּסִים, romanized: Migraš ha-Rusim; Arabic: المسكوبية, romanized: al-Muskubīya; Russian: Русское подворье в Иерусалиме) is one of the oldest districts in central Jerusalem, featuring a large Russian Orthodox church, the Russian-owned Sergei's Courtyard and the premises of the Russian Consulate General in Jerusalem, as well as the site of former pilgrim hostels, some of which are used as Israeli government buildings (such as the Moscovia Detention Centre), and one of which hosts the Museum of Underground Prisoners. The compound was built between 1860 and 1890, with the addition in 1903 of the Nikolai Pilgrims Hospice. It was one of the first structures to be built outside the Old City of Jerusalem.[1] The Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design's main campus is adjacent to the compound.[2]

The Russian Compound covers 68 dunams (17 acres) between Jaffa Road, Shivtei Israel Street, and the Street of the Prophets. After 1890 it was closed by a gated wall, thus the name "compound", but it has long since been a freely accessible central-town district. In October 2008, the Israeli government agreed to transfer ownership of Sergei's Courtyard, one of the main buildings inside the complex, to the Russian government.[3]

History

[edit]A Turkish cavalry parade ground during Ottoman rule, and originally known as “New Jerusalem” (Nuva Yerushama), the "Russian Compound" is a historical area abounding in heritage, scenery and unique environmental features. Throughout history, the hill on which the compound lies had been a prime location for mobilizing forces in order to make attempts to conquer Jerusalem (for instance, in 700 BC by the Assyrian garrison force, and in 70 AD by Roman troops mobilized by Titus).

The compound's construction from 1860 to 1864 was initiated by the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society to serve the large volume of Russian pilgrims to the Holy City. Designed by Russian architect Martin Ivanovich Eppinger, it included a mission (so-called Dukhovnia), consulate, hospital, and hostels.[4] The compound became a centre of government administration for the British Mandate. The women's hostel served as the Mandate's central prison, and now serves as a museum for incarcerated members of outlawed Zionist underground groups such as the Irgun and Lehi.

The Israeli Administrator General Haim Kadmon purchased the Russian Compound in the 1960s, save for the Church of the Holy Trinity and the Sergei Courtyard. The complex was for many years a centre of Jerusalem's nightlife, though the municipality has recently closed the nightclubs in the area and is planning on redeveloping it as a residential area. The municipality's headquarters at Safra Square (Kikar Safra) are themselves located on the edge of the compound, and several departments of the local government have their offices in the district as well.

Ottoman era

[edit]Soon after their conversion to Christianity, the people of Russia began performing pilgrimages to the Holy Land. By the 19th century, thousands of pilgrims flocked annually to the Ottoman-ruled Holy Land, mainly at Easter. In 1911, over 10,000 Russian made the pilgrimage for Easter.[5] The Russian Orthodox Church sent more pilgrims to the Holy Land than any other denomination. Some even made the pilgrimage from Russia on foot.

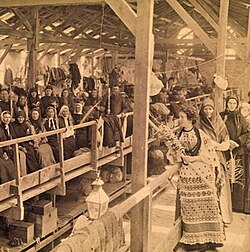

The Russian Compound had begun to develop in the early 19th century with the opening of the first hospital for pilgrims outside of the Old City walls.[dubious – discuss] It hosted a market where local peddlers could sell their wares and services to pilgrims. In 1847 the first Russian Ecclesiastical Mission was sent to Jerusalem, which, in 1857, was officially inaugurated[where?] with the recognition from the Sultan of Turkey. Its purpose was to offer Russian pilgrims spiritual supervision, provide assistance, and sponsor charitable and educational work among the Orthodox Arab population of Palestine and Syria.[citation needed]

In 1858, the entire area of the Compound was sold to the Russian Empire. The Russian state and church during the reign of Czar Alexander II who had become concerned about the Russian pilgrims in the Holy Land, subsequently built numerous hospices, monasteries and churches to handle the flood, including the monumental Russian Compound just north of the Old City, one of the most magnificent sites outside the walls. The location was chosen because of its proximity to the Old City and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher on the boundary between New Jerusalem and the Old City. It covers 68,000 m2 between Jaffa Road, Shivtei Israel Street, and Street of the Prophets.

Between 1860 and 1864 the Marianskaya Women's Hospice was built on the northeast, and the Russian consulate on the southeast side; to the southwest was a hospital, and in a separate building the residence of the Russian Orthodox religious mission with apartments for the archimandrite, the priests and well-to-do pilgrims; to the northwest stood the large Elizabeth Men's Hospice with altogether 2,000 beds.[dubious – discuss][citation needed] Sometimes tents had to be erected to accommodate the huge crowds of pilgrims. Finally the Holy Trinity Cathedral was built in 1872 as the centrepiece of the Compound.

The Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society, based in St. Petersburg, was the initiator and backer of the huge undertaking, and Russian architect Martin Ivanovich Eppinger was responsible for its design, influenced by Byzantine architecture. All the building materials, as well as the furniture, were brought from Russia by a Russian shipping line established especially for that purpose, which also brought shiploads of pilgrims. The large courtyards contained stables, chicken coops, wells and a laundry.[citation needed]

In 1889 the Sergej Imperial Hospice was completed by the Jerusalem-based George Franghia,[6][7][8] head engineer of the province at the time,[9] an additional accommodation with 25 luxuriously furnished rooms for "rich and honourable guests", on a 9 acres (36,000 m2) plot of land to the northeast of and adjacent to the actual compound.[citation needed] It was commissioned by Grand Duke Sergei (1857–1905),[citation needed] brother to Czar Alexander III, and then President of the Orthodox Palestine Society (Pravoslavnoje Palestinskoje Obshchestvo).[10] The splendid building was made entirely out of hewn stone and was referred to as "one of the most marvellous buildings in the city" by the newspapers.[citation needed]

World War I stopped everything. All priests and the entire staff of the Mission were expelled from Palestine as enemy aliens and all the churches were closed. Turkish soldiers occupied the Russian Compound. With the rise of communist rule in the Soviet Union, the stream of Russian pilgrims to Jerusalem ceased almost entirely. The October Revolution had a major impact on everyday life in Jerusalem. It halted not only the flow of pilgrims, but also the money to maintain the Compound. Most of the buildings were rented to the British authorities.

British Mandate

[edit]In 1917, towards the end of World War I, the British conquered Palestine from the Ottomans (Turks) and ruled under an international mandate until 1948. The first High Commissioner of the British Mandate, Herbert Samuel, governed between 1920 and 1925. Zoning measures were instituted creating a lengthy park zone from the Russian Compound towards the Old City and Mount Scopus.[11] Subsequently, there were a further six High Commissioners of Palestine in office until the British Mandate ceased in 1948.

The compound was made one of the bases for the British Mandate in Jerusalem, and became a centre of government administration. All local nationals, most of them Jews, were ordered to abandon their shops and offices. The Russian buildings were converted into government offices. They housed police headquarters and courthouses as well as the Immigration Office.

The women's hospice was converted into the central prison of Jerusalem in response to the Jewish underground, comprising groups like the Haganah, the Palmach, the Lehi, and the Irgun intensifying their activities, which led to many of their members being jailed. Members of the underground were incarcerated here alongside Arab and Jewish criminals before being transferred to the main prison in Acre.

In 1931 the British authorities requested that the chief rabbi appoint a prison chaplain who would visit the captives on Shabbat. Rabbi Aryeh Levine became famous as the "Rabbi of the Prisoners". Every Sabbath, he would walk from his home to the Russian Compound, to conduct services with the prisoners and keep them company. He was known as the "tzaddik (righteous person) of Jerusalem". In 1965, "Rav Aryeh" was honored at a ceremony assembled by the veteran underground resistance fighters. Timed to take place on his 80th birthday, it was held in the courtyard of the old central prison.

After the end of the Second World War, during Cunningham's tenure as High Commissioner, the British army began constructing 'security zones' in the three large cities. In Jerusalem itself, four such zones were set up. The central 'security zone' was set up in the Russian Compound. The entire area was cordoned off by barbed wire fences and entrance was by identity card only. It was nicknamed "Bevingrad" by the Jewish underground after the anti-Zionist British foreign minister Ernest Bevin.

As British control over the political situation in Mandatory Palestine steadily weakened, harsher measures were enacted. The British finally decided to begin executing Jewish underground prisoners. In 1947, two condemned Jews, Meir Feinstein and Moshe Barazani, blew themselves up in the night before their execution with a hand grenade which had been smuggled into the cell inside of an orange.

Immediately after the last British soldiers had left Jerusalem in 1948, underground fighters of the Irgun took over the vacant Generali building on the corner of Jaffa and Shlomzion Hamalka streets. After raising the national flag above the statue of the winged lion on the roof of the building, they turned towards the Russian Compound, where the British intelligence (CID) was. Several members of the Irgun force had been incarcerated in the central prison and felt particular satisfaction in returning there as victors.

On May 15, 1948, during the 1948 Palestine war, the compound was captured by the Haganah with the assistance of the Etzel and Lehi in a campaign known as Operation Kilshon.

State of Israel

[edit]In 1948, after the Soviet Union recognized the state of Israel, Israel returned all Russian church properties on its territory to the Moscow Patriarch, including the Russian Compound. In 1964 the property was purchased by the government of Israel except for the cathedral and one building. The purchase was paid for in $3.5 million worth of oranges since at the time Israel had a shortage of hard currency. The Jerusalem municipality was built here with the adjacent Safra Public Square. Today, the neglected but architecturally striking enclave serves as an Israeli lock-up; at visiting times, families of prisoners can often be seen huddling outside the police barricades. The Ministry of Agriculture, courts, and the Jerusalem's police headquarters are housed in other buildings.

For many years the Russian Compound was a centre of Jerusalem nightlife, featuring pubs with names like Glasnost, Cannabis and Putin. The municipality has recently closed the "pub district" in the neighbourhood of the restaurants and bars of Ben-Yehuda and Jaffa Road, and is planning on redeveloping it as the new business and culture district. Plans include a circular plaza around the cathedral, a shopping center and renovation and redesignation of the historic buildings in the compound.

The creation of a new campus for the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, opened in 2023, was central for this rehabilitation. In 2006, an international architects competition was declared open for design of the future campus which is expected to promote interaction between the students and the surrounding heart of urban life on the line separating east from west in Jerusalem, bringing a student and bohemian population to the city center, and constituting an unusual challenge for designers.

In October 2008 the Israeli government agreed to transfer Sergei's Courtyard to Russia, which had originally also been a part of the Russian compound and which had been housing offices of Israel's Agriculture Ministry and the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel. The government departments housed there were relocated in March 2011. [3]

In 2023 the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design relocated most of its 3,000+ faculty and students to a brand new, 460,000 sq ft SANAA-designed building adjacent to the compound.[12][13]

Buildings

[edit]

Holy Trinity Cathedral

[edit]

The Holy Trinity Cathedral was built as the center of the Russian Compound with funds donated by the people of the Russian Empire. Construction began in 1860, the edifice was consecrated in 1872. The surface of its interior main hall, dome, and two aisles is painted celestial blue with salmon accents and include numerous depictions of saints. The church has four octagonal bell towers. The cathedral is considered to be one of Jerusalem's more distinctive churches.

Sergei Courtyard

[edit]The Sergei Courtyard, at the corner of Heleni HaMalka and Monbaz Street, is a courtyard structure with a Renaissance style imperial tower, named for Grand Prince Sergei (1857–1905), brother of Tsar Alexander III, then President of the Russian Orthodox Palestine Society.[citation needed] Completed in 1889 by architect George Franghia,[7] it was built for pilgrims from the Russian nobility as "Sergej Imperial Hospice".[citation needed] It occupied 9 acres (36,000 m2) of land, and was made entirely out of hewn stone, its 25 luxuriously furnished rooms intended as lodgings for aristocrats. It was referred to as "one of the most marvellous buildings in the city" by the newspapers[which?].[citation needed] Jacob Valero and Company, a local bank founded by a prominent Sephardi Jewish family, financed the construction of the Sergei Building.[14] The building was nationalized under the British Mandate and used as a public works department and passport office. After the establishment of the State of Israel, it was taken over by the Israeli government. Until 2008, it housed offices of the Agriculture Ministry and the Society for the Preservation of Israel Heritage Sites (SPIHS). In 2008, the Israeli government transferred the property of Sergei Courtyard back to the Russian government.[3]

Duhovnia

[edit]

The long building lies south of the cathedral towards the new city hall. Built in 1863 as a hospice, it also hosted the offices of the ecclesiastical mission of the Russian patriarchate, named Duhovnia. It has a courtyard structure with a church (St Alexandra) in the center. The building housed all of Jerusalem's courts, including the Israeli Supreme Court, until 1992. The building is now used only for lower courts and the magistrate court. The Russian Mission used to use the building; presently it still has an office in the back of the building, however its center is now on the Mount of Olives, directly east of the compound.

Southern Gate

[edit]The Southern Gate, between the mission and the hospital on Safra Square, was built in 1890 as part of the perimeter wall of the Russian Compound. It was moved from its original location about 50 metres (160 ft) south of where it now stands as part of the Safra Square Project and the new City hall.

Hospital

[edit]

13 Safra Square

Russian Consulate

[edit]The Russian Consulate, on Shivtei Yisraʾel Street behind the municipality complex, was erected in stages beginning in 1860, and combines European characteristics with local building techniques. From 1953 to 1973 it housed the school of pharmacy, later laboratories, of the Hebrew University.

Elisabeth Courtyard hospice for men

[edit]A courtyard structure built in 1864 as a hostel able to accommodate about 300 pilgrims is located on today's Monbaz Street. Above the Neoclassical entrance is an inscription marking it as "Elisbeth Courtyard" and the emblem of the Imperial Russian Orthodox Palestine Society. It houses now the police headquarters.

Northern Gate

[edit]The Northern Gate is opposite the Sergei Building. Around the compound was a perimeter wall with two formal gates at north and south, built in 1890. Only one of the two northern gatehouses has survived. The other was pulled down in the 1970s. On the façade is the emblem of the Imperial Russian Orthodox Palestine Society.

Marianskaya Courtyard hospice for women

[edit]The hostel for Russian women pilgrims, at 1 Misheol Hagvurah Street, was built in 1864 in the Neoclassical style. At the front of the building one can see a Russian inscription that translates as "Marianskaya women's hospice" and the symbol of the Imperial Russian Orthodox Palestine Society above the entrance. With long hallways leading to separate rooms, it was an ideal layout for a hostel, or a prison, as used by the British during their mandate in Palestine.

Over the course of the British occupation, hundreds of prisoners, both simple criminals and political, passed through its gates. Jews and Arabs were incarcerated together. Executions for capital crimes were commonplace, but only for Arabs. While the facility housed many death-row inmates captured from Jewish underground organizations, Jews sentenced to death were sent to Acre prison for the actual executions. The British, fearful of the Jewish reaction to executions in the Holy City, never used the gallows of the prison for Jews. Prisoners from the Jewish underground organizations were often put to work making coffins and gravestones for the very same British policemen and soldiers they had killed. As the guards used to tell them, "What you start on the outside, you finish on the inside." The building now houses the Underground Prisoners Museum. The barbed wire fence, bars and inscription "Central Prison Jerusalem" on the door are from the British Mandatory period.

Nikolai Courtyard – Pilgrims Hospice

[edit]In 1903 another hospice for Russian pilgrims was built, the Nikolai Pilgrims Hospice, named for Tsar Nicholas II, which was large enough to hold 1,200 guests. In the British Mandate period, part of it was used as a police headquarters and as government offices. Later it was the British intelligence headquarters, blown up twice by the Jewish underground organisation Irgun under Menachem Begin in 1945.

Archaeology

[edit]In front of the police headquarters on Shneor Cheshin Street is a colossal monolithic column dating either from the Second Temple or the Byzantine period. The column was discovered in 1871. In ancient times there was a quarry here, and a relic of it is still to be seen in the form of that column fully 12 m (39 ft) long which broke while it was being quarried and was left in situ, still embedded in the natural rock. The column was presumably destined either for the colonnades of the Herodian Temple or - as a number of capitals found here suggest - for a building of the Theodosian period (second half of the 4th century). It is popularly known as the "Finger of Og".

Recent archaeological excavations suggest that Jerusalem's ancient "Third Wall," built by Agrippa I, extended as far as the Russian Compound, seeing that the newly uncovered section of a wall, measuring 6.2 feet (1.9 meters) in width, was littered with large ballista stones (stones used as projectiles with a type of crossbow) and sling stones. Pottery discovered at the site also suggests that this battlefield dates back to Roman times. They also discovered the remains of a watchtower along the wall.[15]

Another excavation uncovered a sealed water cistern containing the remains of at least 124 individuals, including men, women, children, and fetuses. The majority of skeletons showed signs of decapitation or sharp-force trauma, suggesting a large-scale massacre rather than deaths in battle.[16] Based on ceramic assemblages and stratigraphy, the burial dates to the late 2nd or early 1st century BCE, during the reign of the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus. These findings may represent archaeological evidence of political violence in Hasmonean Jerusalem, potentially linked to the Judean Civil War, as described by Josephus and in the Dead Sea Scrolls.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kark, Ruth; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948. Wayne State University Press. pp. 74, table on p.82–86. ISBN 0-8143-2909-8.

The beginning of construction outside the Jerusalem Old City in the mid-19th century was linked to the changing relations between the Ottoman government and the European powers. After the Crimean War, various rights and privileges were extended to non-Muslims who now enjoyed greater tolerance and more security of life and property. All of this directly influenced the expansion of Jerusalem beyond the city walls. From the mid-1850s to the early 1860s, several new buildings rose outside the walls, among them the mission house of the English consul, James Finn, in what came to be known as Abraham's Vineyard (Kerem Avraham), the Protestant school built by Bishop Samuel Gobat on Mount Zion; the Russian Compound; the Mishkenot Sha'ananim houses: and the Schneller Orphanage complex. These complexes were all built by foreigners, with funds from abroad, as semi-autonomous compounds encompassed by walls and with gates that were closed at night. Their appearance was European, and they stood out against the Middle-Eastern-style buildings of Palestine.

- ^ "The New Building Revolutionizing Jerusalem". Haaretz. Retrieved 2023-12-17.

- ^ a b c "Israel vacates Sergei courtyard ahead of Netanyahu's Moscow visit this week". Haaretz.

- ^ Jerusalem: Architecture in the late Ottoman Period

- ^ "The Russians in Jerusalem". Parallel Histories. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ Wolf Moskovich; С Шварцбанд [S. Shvartsband]; Анатолий Алексеевич Алексеев [Anatoliy Alekseevich Alekseev], eds. (1993). Евреи И Славяне [Jews & Slavs]. Volume 6 of Jews and Slavs, Institute of Slavic and Balkan Studies (USSR Academy of Sciences); Volume 11 of Studi slavi. В. Я Петрухин [V. Y. Petrukhin]. Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. pp. 365, 370 fn. 35. ISBN 978-961-6182-86-7. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Russian Representation Church in Jerusalem to Reopen after Years of Restoration". OrthoChristian.com. 18 July 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ "Virtual tour "Church of Saint Alexander Nevskiy", Jerusalem". Vela De Jerusalen. 12 October 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Dimitriadis, Sotirios (2018). "The Tramway Concession of Jerusalem, 1908–1914: Elite Citizenship, Urban Infrastructure, and the Abortive Modernization of a Late Ottoman City". Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940. BRILL. pp. 475–489. doi:10.1163/9789004375741_030. ISBN 978-90-04-37574-1. S2CID 201369914. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Segev, Tom (9 October 2008). "Portrait of a Duke". Haaretz. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ Dovid Rossoff. (2004). Where heaven touches earth : Jewish life in Jerusalem from Medieval times to the present. Jerusalem : Guardian Press; Nanuet, NY : Distributed by Feldheim Publishers. 6th rev. ed. ISBN 978-0-87306-879-6. p. 437.

- ^ "The New Campus". Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem. Retrieved 2023-12-17.

- ^ "Bezalel opens the semester at the new campus: The President of the Academy addresses the celebration alongside recent events in the country". Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem. Retrieved 2023-12-17.

- ^ "Post boxes and Power in Jerusalem". Parallel Histories. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- ^ Gannon, Megan (October 23, 2016). "Scientists locate site where ancient Roman armies breached Jerusalem walls". Live Science Contributor. Live Science. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Lieberman, Tehillah; Arbiv, Kfir; Nagar, Yossi (2020-01-02). "The Wrath of the Lion: Evidence of a Mass-Burial in Hasmonean Jerusalem". Tel Aviv. 47 (1): 89–107. doi:10.1080/03344355.2020.1707448. ISSN 0334-4355.

Further reading

[edit]- Ely Schiller (ed.): The Heritage of the Holy Land. A rare collection of photographs from the Russian Compound 1905-1910, Arie Publishing House, Jerusalem, 1982

- David Kroyanker (ed.): The Russian Compound: Toward the Year 2000. From Russian Pilgrimage Center to a Focus of Urban Activity The Jerusalem Municipality, 1997

- David Kroyanker: Jerusalem Architecture (p. 132-135, The Russians). (Introduction by Teddy Kollek), Keter Publishing House Ltd., 1994, 2002

- Yehoshua Ben-Arieh: Jerusalem in the 19th century. Emergence of the New City, St Martin's Press New York/Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Jerusalem, 1986

- S. Graham: With the Russian Pilgrims to Jerusalem, London 1914

- Aviva Bar-Am: Return to Bevingrad, Jerusalem Post (Magazine), September 19, 2003