Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Semiperfect number

View on WikipediaIn number theory, a semiperfect number or pseudoperfect number is a natural number n equal to the sum of all or some of its proper divisors. A semiperfect number equal to the sum of all its proper divisors is a perfect number.

Key Information

The first few semiperfect numbers are: 6, 12, 18, 20, 24, 28, 30, 36, 40, ... (sequence A005835 in the OEIS)

Properties

[edit]- Every multiple of a semiperfect number is semiperfect.[1] A semiperfect number not divisible by any smaller semiperfect number is called primitive.

- Every number of the form 2mp for a natural number m and an odd prime number p such that p < 2m+1 is also semiperfect.

- In particular, every number of the form 2m(2m+1 − 1) is semiperfect, and is indeed perfect if 2m+1 − 1 is a Mersenne prime.

- The smallest odd semiperfect number is 945.

- A semiperfect number is necessarily either perfect or abundant. An abundant number that is not semiperfect is called a weird number.

- Except for 2, all primary pseudoperfect numbers are semiperfect.

- Every practical number that is not a power of two is semiperfect.

- The natural density of the set of semiperfect numbers exists.[2]

Primitive semiperfect numbers

[edit]A primitive semiperfect number (also called a primitive pseudoperfect number, irreducible semiperfect number or irreducible pseudoperfect number) is a semiperfect number that has no semiperfect proper divisor.[2]

The first few primitive semiperfect numbers are 6, 20, 28, 88, 104, 272, 304, 350, ... (sequence A006036 in the OEIS)

There are infinitely many such numbers. All numbers of the form 2mp, with p a prime between 2m and 2m+1, are primitive semiperfect, but not all primitive semiperfect numbers follow this form; for example, 770.[1][2] There are infinitely many odd primitive semiperfect numbers, the smallest being 945. There are infinitely many primitive semiperfect numbers that are not harmonic divisor numbers.[1]

Every semiperfect number is a multiple of a primitive semiperfect number.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Zachariou & Zachariou (1972).

- ^ a b c Guy (2004).

References

[edit]- Friedman, Charles N. (1993). "Sums of divisors and Egyptian fractions". Journal of Number Theory. 44 (3): 328–339. doi:10.1006/jnth.1993.1057. MR 1233293. Zbl 0781.11015.

- Guy, Richard K. (2004). Unsolved Problems in Number Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-20860-7. OCLC 54611248. Zbl 1058.11001. Section B2.

- Sierpiński, Wacław (1965). "Sur les nombres pseudoparfaits". Mat. Vesn. Nouvelle Série (in French). 2 (17): 212–213. MR 0199147. Zbl 0161.04402.

- Zachariou, Andreas; Zachariou, Eleni (1972). "Perfect, semiperfect and Ore numbers". Bull. Soc. Math. Grèce. Nouvelle Série. 13: 12–22. MR 0360455. Zbl 0266.10012.

External links

[edit]Semiperfect number

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Examples

Definition

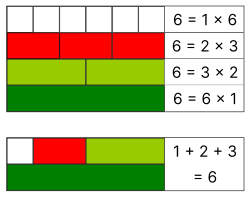

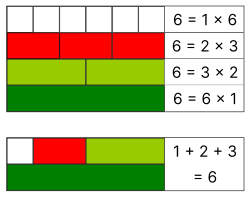

A semiperfect number, also known as a pseudoperfect number, is a natural number that is equal to the sum of some of its proper divisors (or all of them, in the case of perfect numbers).[2]Basic Examples

Semiperfect numbers include both perfect numbers, where all proper divisors sum to the number, and other cases where only a proper subset does so. The smallest semiperfect number is 6, a perfect number whose proper divisors are 1, 2, and 3, summing to .[1] The next few even semiperfect numbers are 12, 18, 20, 24, 28, and 30.[1] For 12, one subset of proper divisors is {1, 2, 3, 6}, summing to 12; another is {2, 4, 6}.[3] For 18, the subset {3, 6, 9} sums to 18.[1] For 20, the subset {1, 4, 5, 10} sums to 20, though other subsets also exist.[2] The number 28 is perfect, with proper divisors 1, 2, 4, 7, and 14 summing to 28.[1] For 30, a subset such as {5, 10, 15} sums to 30.[4] Unlike even semiperfect numbers, which appear early in the natural numbers, odd semiperfect numbers are rarer. The smallest odd semiperfect number is 945.[1] Its proper divisors are 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 15, 21, 27, 35, 45, 63, 105, 135, 189, and 315, summing to 975.[5] One subset summing to 945 is {1, 5, 7, 9, 15, 21, 35, 45, 63, 105, 135, 189, 315}.[5] The sequence of semiperfect numbers is given by OEIS A005835.[1]Mathematical Properties

General Properties

A semiperfect number greater than 1 is either perfect or abundant, as the sum of all its proper divisors exceeds the number (for abundant) or equals it (for perfect), allowing subsets to sum precisely to the number, whereas deficient numbers have total proper divisor sum less than the number itself, precluding such a subset.[3] The collection of semiperfect numbers is closed under multiplication: if is semiperfect, then so is any positive integer multiple for . This holds because if a subset of the proper divisors of sums to , then the scaled subset consists of proper divisors of (each since ) and sums to .[2] Certain forms guarantee semiperfectness; for instance, every integer of the form , where and is an odd prime with , is semiperfect. In such cases, the divisor set—powers of 2 up to and their multiples by up to —permits a subset summing to , leveraging the binary structure of the powers of 2 and the size of .[2] The semiperfect numbers possess a natural density that exists and is positive.[6] Every practical number except powers of 2 is semiperfect, as practical numbers enable every integer from 1 to their abundance to be written as a sum of distinct proper divisors, and non-powers-of-2 practical numbers are abundant with , thus allowing a sum to itself.[7]Relation to Abundant and Perfect Numbers

Semiperfect numbers occupy a specific position in the hierarchy of numbers classified by their divisor sums. A perfect number is one where the sum of its proper divisors equals the number itself, denoted as , or equivalently , where is the sum of all divisors of .[8] Semiperfect numbers include all perfect numbers and extend to certain abundant numbers, where an abundant number satisfies (or ), but with the additional property that some subset of its distinct proper divisors sums exactly to .[8] This subset sum condition distinguishes semiperfect numbers from the broader class of abundant numbers, positioning them as a bridge between perfect numbers and those abundant numbers lacking such a subset, known as weird numbers.[8] Weird numbers are defined precisely as abundant numbers that are not semiperfect, meaning no combination of their distinct proper divisors sums to the number itself.[8] The smallest weird number is 70, and all known weird numbers are even, with no odd weird numbers identified despite extensive computational searches up to .[8][9] This contrast highlights the rarity and elusiveness of weird numbers within the abundant category, as semiperfect numbers encompass the majority of abundant instances where subset sums are feasible. Within the subclass of primitive abundant numbers—those abundant numbers whose proper divisors are all deficient—further partitioning occurs: such numbers are either primitive semiperfect (with no proper pseudoperfect divisors) or weird.[8] The set of weird numbers has positive asymptotic density, implying their infinite prevalence, though they form a proper subset of abundant numbers excluding the semiperfect ones.[8] This taxonomic relation underscores the nuanced structure of abundance, where semiperfect numbers provide a measurable criterion for "balance" amid excess divisor sums.Primitive Semiperfect Numbers

Definition

A primitive semiperfect number is a semiperfect number—defined as a natural number equal to the sum of some of its proper divisors—such that none of its proper divisors is semiperfect.[2][10] Equivalently, a primitive semiperfect number is not divisible by any other semiperfect number besides 1.[11] Every semiperfect number is a multiple of some primitive semiperfect number.[7] All known even perfect numbers, which are themselves semiperfect, are primitive semiperfect numbers.[12]Properties and Examples

Primitive semiperfect numbers exhibit several notable properties. There are infinitely many such numbers, as demonstrated by constructions of the form , where is a prime chosen such that the number is semiperfect but no proper divisor is.[8] Additionally, there are infinitely many odd primitive semiperfect numbers.[10] The smallest primitive semiperfect numbers are 6, 20, 28, 88, 104, 272, 304, and 350 (sequence A006036 in the OEIS).[11] The smallest odd primitive semiperfect number is 945.[11] Most even primitive semiperfect numbers take the form with an odd prime, but exceptions exist, such as 770 = , which has four distinct prime factors.[11]History and Computation

Historical Development

The concept of semiperfect numbers originates as a generalization of perfect numbers, whose study dates to ancient Greece. Euclid described perfect numbers around 300 BCE in Book VII of his Elements as positive integers equal to the sum of their proper divisors, establishing a foundational framework in number theory for exploring divisor sums. This early work on perfect numbers provided the conceptual roots for later extensions, including those involving subsets of divisors, though such ideas remained informal for centuries. The formalization of semiperfect numbers occurred in the mid-20th century amid broader investigations into abundant numbers, where the sum of all proper divisors exceeds the number itself, naturally leading to questions about subsets that sum precisely to the number. Early mentions of these subset sum properties appeared in studies of abundant and deficient numbers, highlighting their role in bridging perfect and abundant classifications. The term "pseudoperfect number" was coined by Wacław Sierpiński in 1965 in his paper "Sur les nombres pseudoparfaits," published in Matematički Vesnik.[2] This introduced a precise terminology for numbers expressible as the sum of some of their proper divisors, building directly on the perfect number tradition. In 1972, Andreas Zachariou and Eleni Zachariou proposed the alternative term "semiperfect number" in their paper "Perfect, semiperfect and Ore numbers," published in the Bulletin of the Greek Mathematical Society.[13] Their work further contextualized semiperfect numbers alongside related concepts like Ore's harmonic numbers. The recognition of the primitive subclass—semiperfect numbers none of whose proper divisors are semiperfect—emerged in the 1970s and 1980s through key contributions in the literature on divisor subset sums. Notably, S. J. Benkoski and Paul Erdős defined and analyzed primitive pseudoperfect numbers in their 1974 paper "On weird and pseudoperfect numbers," published in Mathematics of Computation, proving properties such as the convergence of the sum of their reciprocals.[6] This marked a significant advancement in understanding the structure and distribution of semiperfect numbers.Known Numbers and Searches

The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS) catalogs semiperfect numbers in sequence A005835 and primitive semiperfect numbers in A006036.[1][11] Sequence A005835 includes over 10,000 terms, with all even semiperfect numbers enumerated up to at least 10^6, where they comprise the even abundant numbers excluding the rare even weird numbers. For primitive semiperfect numbers, A006036 lists 73 terms up to 4970, including both even and odd examples, with computational methods confirming all such numbers up to 5000. Odd semiperfect numbers are sparser and computationally more challenging to identify due to the scarcity of odd abundant numbers, but all known odd abundant numbers below 10^6 (1996 in total) are semiperfect.[14] The smallest odd semiperfect number is 945, followed by others such as 1575 and 2205.[14] Extensive searches have identified all odd semiperfect numbers up to 10^21, equating to all odd abundant numbers in this range, as no odd weird numbers have been discovered.[15] These efforts rely on sieving techniques to first identify abundant candidates before verifying semiperfect status, with no additional odd semiperfect numbers reported beyond established lists as of 2022. Primitive odd semiperfect numbers, starting with 945, are also included in these enumerations, with A006036 noting their alignment with odd primitive abundant numbers up to known bounds.[11] Determining whether a number is semiperfect involves solving the subset sum problem over its proper divisors to check if any subset sums exactly to the number, a task that is NP-complete in general due to the exponential possibilities in subset selection. However, for practical computation with numbers up to 10^21, dynamic programming algorithms are feasible, achieving efficiency in O(d(n) * n) time where d(n) is the number of divisors (typically small, under 100 for such n), by building a boolean array tracking achievable sums from the divisors.[16] These methods enable exhaustive searches, though scaling to higher bounds requires optimized sieves to prune non-abundant candidates early. Open questions include the precise density of semiperfect numbers, which exists and equals the density of abundant numbers minus that of weird numbers, estimated positively but with refinements to weird number density post-2000 showing semiperfects comprise most abundants.[8] Paul Erdős proved the existence of infinitely many odd primitive semiperfect numbers, resolving one infinitude question, though the overall distribution and potential gaps in large odd examples remain unexplored.[8] No significant post-2020 discoveries of new odd semiperfect or primitive variants have emerged, with ongoing searches focusing on confirming the absence of odd weird numbers to solidify these classifications.[15]References

- https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Perfect_Number_is_Primitive_Semiperfect