Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

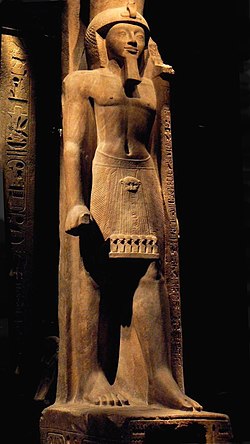

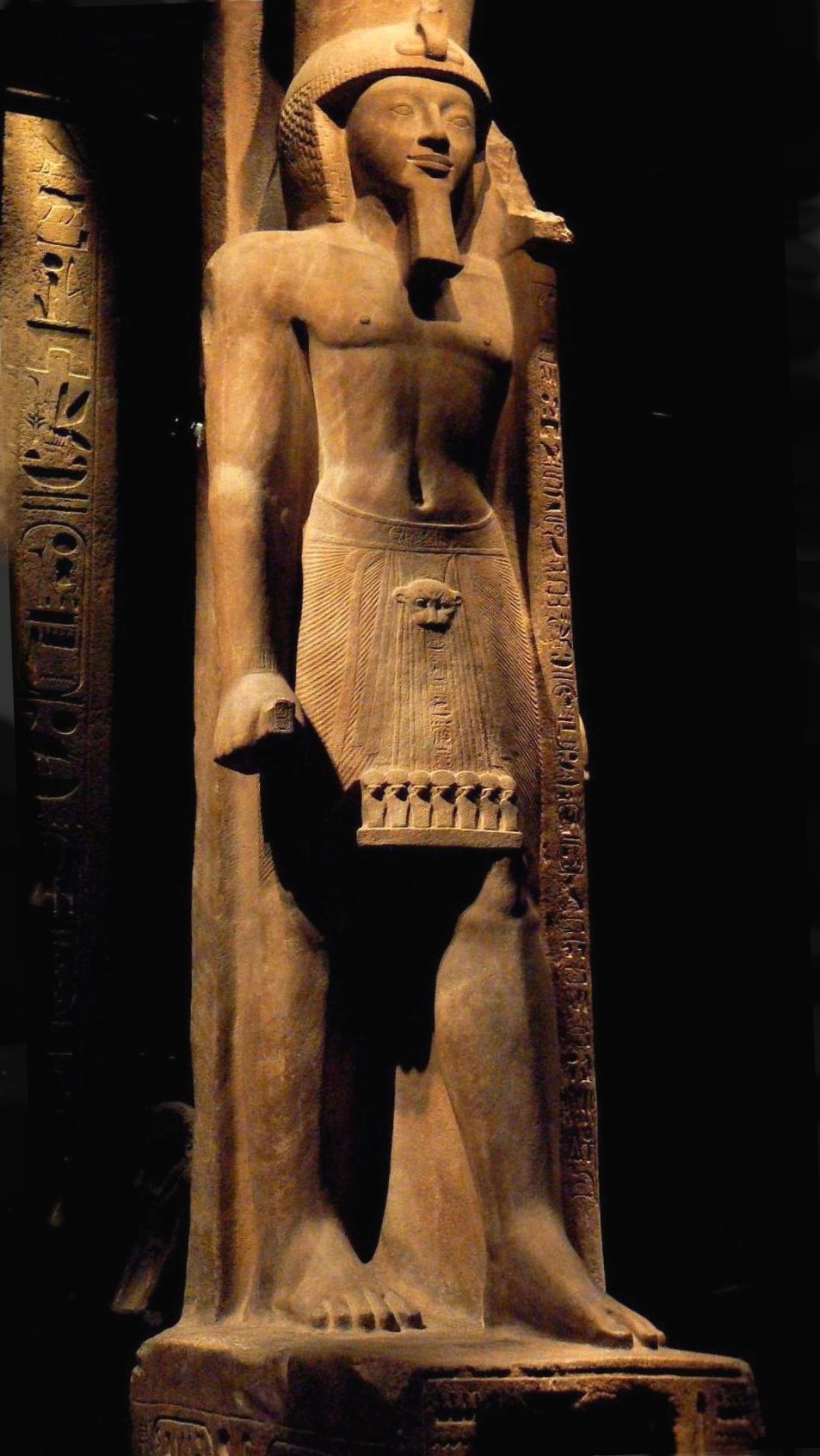

Seti II

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Seti II (or Sethos II) was the fifth pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt and reigned from c. 1203 BC to 1197 BC.[1] His throne name, Userkheperure Setepenre, means "Powerful are the manifestations of Re, the chosen one of Re."[4] He was the son of Merneptah and Isetnofret II and occupied the throne during a period known for dynastic intrigue and short reigns, and his rule was no different. Seti II had to deal with many serious plots, most significantly the accession of a rival king named Amenmesse, possibly a half brother, who seized control over Thebes and Nubia in Upper Egypt during his second to fourth regnal years.

Contest for the throne

[edit]Evidence that Amenmesse was a direct contemporary with Seti II's rule—rather than Seti II's immediate predecessor—includes the fact that Seti II's royal KV15[5] tomb at Thebes was deliberately vandalised with many of Seti's royal names being carefully erased here during his reign.[6] The erasures were subsequently repaired by Seti II's agents. This suggests that Seti II's reign at Thebes was interrupted by the rise of a rival: king Amenmesse in Upper Egypt.[7] Secondly, the German scholar Wolfgang Helck has shown that Amenmesse is only attested in Upper Egypt by several Year 3 and a single Year 4 ostracas; Helck also noted that no Year 1 or Year 2 ostracas from Deir El Medina could legitimately be assigned to Amenmesse's reign.[8] This conforms well with the clear evidence of Seti II's control over Thebes in his first two years, which is attested by various documents and papyri. In contrast, Seti II is absent from Upper Egypt during his third and fourth years which are notably unattested—presumably because Amenmesse controlled this region during this time.[9] Seti II is only attested in Upper Egypt in Regnal Year 1, 2, 5 and 6 of his reign while the usurper Amenmesse likely seized control of Upper Egypt and the Valley of the Kings sometime between Year 2 until Year 5 of Seti II's reign when he was finally defeated.

Finally, and most importantly, it is well known that the chief foreman of Deir el-Medina, a certain Neferhotep, was killed in the reign of king Amenmesse on the orders of a certain 'Msy' who was either Amenmesse himself or one of this king's agents, according to Papyrus Salt 124.[10] However, Neferhotep is attested in office in the work register list of Ostraca MMA 14.6.217, which also recorded Seti II's accession to the throne and was later reused to register workers' absences under this king's reign.[11] If Seti II's 6-year reign followed that of the usurper Amenmesse, then this chief foreman would not have been mentioned in a document which dated to the start of Seti II's reign since Neferhotep was already dead.[12] This indicates that the reigns of Amenmesse and Seti II must have partly overlapped with one another and suggests that both rulers were rivals who were fighting each another for the throne of Egypt.

During the second to fourth years of Amenmesse/Seti II's parallel reigns, Amenmesse gained the upper hand and seized control over Upper Egypt and Nubia; he ordered Seti II's tomb in the Valley of the Kings to be vandalised. Prior to his fifth year, however, Amenmesse was finally defeated by his rival, Seti II, who was the legitimate successor to the throne since he was Merneptah's son. Seti II, in turn, launched a damnatio memoriae campaign against all inscriptions and monuments belonging to both Amenmesse and this king's chief supporters in Thebes and Nubia, which included a certain Khaemter, a former Viceroy of Kush, who had served as Amenmesse's Vizier. Seti II's agents completely erased both scenes and texts from KV10, the royal tomb of Amenmesse.[13] Vizier Khaemter's scenes in Nubia which were carved when he served as the Viceroy of Kush were so thoroughly erased that until Rolf Krauss' and Labib Habachi's articles were published in the 1970s,[14][15] his career here as viceroy was almost unknown, notes Frank J. Yurco.[16]

Reign

[edit]

Seti II promoted Chancellor Bay to become his most important state official and built 3 tombs – KV13, KV14, and KV15 – for himself, his Senior Queen Tausert and Bay in the Valley of the Kings. This was an unprecedented act on his part for Bay, who was of Syrian descent and was not connected by marriage or blood ties to the royal family. Because Seti II had his accession between II Peret 29 and III Peret 6 while Siptah—Seti II's successor—had his accession around late IV Akhet to early I Peret 2,[17] Seti's 6th and final regnal year lasted about 10 months; therefore, Seti II ruled Egypt for 5 years and 10 months or almost 6 full years when he died.

Due to the relative brevity of his reign, Seti's tomb was unfinished at the time of his death. Tausert later rose to power herself after the death of Siptah, Seti II's successor. According to an inscribed ostraca document from the Deir el-Medina worker's community, Seti II's death was announced to the workmen by "The [Chief of] police Nakht-min" on Year 6, I Peret 19 of Seti II's reign.[18] Since it would have taken time for the news of Seti II's death to reach Thebes from the capital city of Pi-Ramesses in Lower Egypt, the date of I Peret 19 only marks the day the news of the king's death reached Deir el-Medina.[19] Seti II likely died sometime late in IV Akhet or early in I Peret; Wolfgang Helck and R.J. Demarée have now proposed I Peret 2 as the date of Seti II's actual death,[20] presumably since it is 70 days before the day of his burial. From a graffito written in the first corridor of Twosret's KV14 tomb, Seti II was buried in his KV15 tomb on "Year 1, III Peret day 11" of Siptah's reign.[21]

Seti II's earliest prenomen in his First Year was 'Userkheperure Setepenre'[22] which is written above an inscription of Messuy, a Viceroy of Nubia under Merneptah, on a rock outcropping at Bigeh Island. However, Messuy's burial in Tomb S90 in Nubia has been discovered to contain only funerary objects naming Merneptah which suggests that 1) Messuy may have died during Merneptah's reign and 2) Seti II may have merely associated himself with an official who had actively served his father as Viceroy of Kush. Seti II soon changed his royal name to 'Userkheperure Meryamun', which was the most common form of his prenomen.

Two important papyri date from the reign of Seti II. The first of these is the "Tale of Two Brothers", a fabulous story of troubles within a family on the death of their father, which may have been intended in part as political satire on the situation of the two half brothers. The second is the records of the trial of Paneb. Neferhotep, one of the two chief workmen of the Deir el-Medina necropolis, had been replaced by Paneb, his troublesome son-in-law. Many crimes were alleged by Neferhotep's brother—Amennakhte—against Paneb in a violently worded indictment preserved in papyrus now in the British Museum. If Amennakhte's testimony can be trusted, Paneb had allegedly stolen stone from the tomb of Seti II while still working on its completion—for the embellishment of his own tomb—besides purloining or damaging other property belonging to that monarch. Paneb was also accused of trying to kill Neferhotep, his adopted father-in-law, despite being educated by the latter and after the murder of Neferhotep by 'the enemy,' Paneb had reportedly bribed the Vizier Pra'emhab in order to usurp his father's office. Whatever the truth of these accusations, it is clear that Thebes was going through very troubled times. There are references elsewhere to a 'war' that had occurred during these years, but it is obscure to what this word alludes—perhaps to no more than internal disturbances and discontent. Neferhotep had complained of Paneb's attacks on himself to the vizier Amenmose, presumably a predecessor of Pra'emhab, whereupon Amenmose had punished Paneb. This trouble-maker had then brought a complaint before 'Mose' (i.e., 'Msy'), who then acted to remove Pra'emhab from his office. Evidently this 'Mose' must have been a person of the highest importance, perhaps the king Amenmesse himself or a senior ally of the king.

Seti II also expanded the copper mining at Timna Valley in Edom, building an important temple to Hathor, the cow goddess, in the region. It was abandoned in the late Bronze Age collapse, where a part of the temple seems to have been used by Midianite nomads, linked to the worship of a bronze serpent discovered in the area.[23] Seti II also founded a station for a barge on the courtyard in front of the pylon II at Karnak, and chapels of the Theban Triad – Amun, Mut and Khonsu.

Wives and treasure

[edit]Of the wives of Seti II, Tausert and Takhat seem certain. Tausert would rule as regent for Siptah and later as Pharaoh. Her name is recorded in Manetho's Epitome as a certain 'Thuoris' who is assigned a reign of 7 years.

Takhat bears the title of King's Daughter which would make her the offspring of either Ramesses II or Merenptah. A list of princesses dated to Year 53 of Ramesses II names a Takhat who is not included in earlier lists. This would make her about the same age or younger than Seti II. The traditional view has been that the rivals were half-brothers, with Takhat as Queen to Merenptah and mother to Amenmesse while the mother of Seti II was Isetnofret II.

Takhat is shown on several statues of Amenmesse and on one of these, she is called King's Daughter and King's Wife with the word 'wife' inscribed over 'Mother'. According to Aidan Dodson the title was recarved when Seti regained control and usurped the statue. This would seem to indicate that Takhat was married to Seti and that Amenmesse was Seti's son and usurped the throne from his own father.[24] Dodson allows that there may have been two women named Takhat, but the treatment of the image of Takhat makes it unlikely.

For many years, a certain Tiaa was also accepted as a wife of Seti II and mother of Siptah. This was based on a number of funerary objects found in the tomb of Siptah bearing the name of Tiaa as King's Wife and King's Mother. However, it now seems that these items washed into Siptah's tomb from the nearby tomb, KV32, as the result of an accidental breakthrough. KV32 is the tomb of the wife of Thutmose IV, Tiaa.[25]

In January 1908, the Egyptologist Edward R. Ayrton, in an excavation conducted for Theodore M. Davis, discovered a small burial in tomb KV56 which Davis referred to as 'The Gold Tomb' in his publication of the discovery in the Valley of the Kings; it proved to contain a small cache of jewelry that featured the name of Seti II.[26] A set of "earrings, finger-rings, bracelets, a series of necklace ornaments and amulets, a pair of silver 'gloves' and a tiny silver sandal" were found within this tomb.[27]

Mummy

[edit]In April 2021 his mummy was moved from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization along with those of 17 other kings and 4 queens in an event termed the Pharaohs' Golden Parade.[28]

Bibliography

[edit]- Gabriella Dembitz, The Decree of Sethos II at Karnak : Further Thoughts on the Succession Problem after Merenptah, in: In: K. Endreffy – A. Gulyás (eds.): Proceedings of the Fourth Central European Conference of Young Egyptologists. 31 August - 2 September 2006, Budapest. Studia Aegyptiaca 18. 91 – 108, 2007.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Seti II on digital Egypt

- ^ Peter Clayton, Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1994. p.158

- ^ "Seti II". Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ Clayton, p.158

- ^ "KV 15 (Sety II)". Theban Mapping Project. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Aidan Dodson, "The Decorative Phases of the Tomb of Sethos II and their Historical Implications", Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 85 (1999), pp. 136–138

- ^ Dodson, p. 131

- ^ Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss & David Warburton (editors), Handbook of Ancient Egyptian Chronology (Handbook of Oriental Studies), Brill: 2006, p.213

- ^ E. F. Wente & C. C. Van Siclen, "A Chronology of the New Kingdom", Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes, January 12, 1977, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 39, Chicago: Oriental Institute, p.252

- ^ Jac Janssen, "Amenmesse and After: The chronology of the late Nineteenth Dynasty Ostraca", in Village Varia. Ten Studies on the History and Administration of Deir el-Medina (Egyptologische Utigaven 11), Leiden; 1997, pp. 99–109

- ^ Janssen, p.104

- ^ Janssen, p.100

- ^ Otto Schaden, "Amenmesse Project Report, "ARCE Newsletter", No.163 (Fall 1993) pp. 1–9

- ^ Rolf Krauss, "Untersuchungen zu König Amenmesse", Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 5 (1977) pp. 131–174.

- ^ Labib Habachi, "King Amenmesse and Viziers Amenmose and Kha'emtore: Their Monuments and Place in History", Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 34 (1978) pp. 58–67

- ^ Frank Joseph Yurco, "Was Amenmesse the Viceroy of Kush, Messuwy?" Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 39 (1997), p. 56

- ^ Jürgen von Beckerath, Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten, MAS:Philipp von Zabern, (1997), p.201

- ^ KRI IV: 327. II.22-28, §57 (A.17)

- ^ Jacobus J. Janssen, Village Varia: Ten Studies on the History and Administration of Deir el-Medina, Egyptologische Uitgaven 11 (Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 1997), 153-54

- ^ Wolfgang Helck, "Begräbnis Pharaos," in The Intellectual Heritage of Egypt: Studies Presented to László Kákosy by Friends and Colleagues on the Occasion of his 60th Birthday, ed. Ulrich Luft, (Budapest: La Chair d’Égyptologie de l’Université Eötvös Loráno de Budapest, 1992), 270, n.12. See also R.J. Demarée, "The King is Dead – Long Live the King," GM 137 (1993): p.52

- ^ Hartwig Altenmüller, "Bemerkungen zu den neu gefundenen Daten im Grab der Königin Twosre (KV 14) im Tal der Könige von Theben," pp.147-148, Abb. 19. Cf. "Der Begräbnistag Sethos II," SAK 11 (1984): 37-38 & "Das Graffito 551 aus der thebanischen Nekropole," SAK 21 (1994): pp.19-28

- ^ Frank Joseph Yurco, Was Amenmesse the Viceroy of Kush, Messuwy? JARCE 39 (1997), pp.49-56

- ^ Magnusson, Magnus, "Archaeology of the Bible Lands" (BBC Books)

- ^ Dodson, A.; Poisoned Legacy: The Decline and Fall of the Nineteenth Egyptian Dynasty, American University Press in Cairo, 2010. Appendix 4, p 40

- ^ Dodson, A, (2010), p 91

- ^ Davis, T. M., The Tomb of Sipthah, the Monkey Tomb and the Gold Tomb, No.4, Bibân el Molûk, Theodore M. Davis' Excavations, A. Constable, London, 1908

- ^ Reeves, Nicholas (2001). "Re-excavating 'The Gold Tomb'". Nicholasreeves.com. University College London. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009.

- ^ Parisse, Emmanuel (5 April 2021). "22 Ancient Pharaohs Have Been Carried Across Cairo in an Epic 'Golden Parade'". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

External links

[edit] Media related to Seti II at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Seti II at Wikimedia Commons