Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

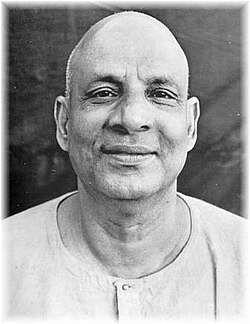

Sivananda Saraswati

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Be Good, do Good, be kind, be compassionate.

Swami Sivananda Saraswati (IAST: Svāmī Śivānanda Sarasvatī; 8 September 1887 – 14 July 1963[1]), also called Swami Sivananda, was a yoga guru,[2] a Hindu spiritual teacher, and a proponent of Vedanta. Sivananda was born in Pattamadai, in the Tirunelveli district of modern Tamil Nadu, and was named Kuppuswami. He studied medicine and served in British Malaya as a physician for several years before taking up monasticism.

He was the founder of the Divine Life Society (DLS) in 1936, Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy (1948), and the author of over 200 books on yoga, Vedanta, and a variety of subjects. He established Sivananda Ashram, the headquarters of the DLS, on the bank of the Ganges at Muni Ki Reti, 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) from Rishikesh, and lived most of his life there.[3][4][5]

Sivananda Yoga, the yoga form propagated by his disciple Vishnudevananda, is now spread in many parts of the world through Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres. These centres are not affiliated with Sivananda's ashrams, which are run by the Divine Life Society.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Swami Sivananda was born as Kuppuswami to a Brahmin family[6] on 8 September 1887. His birth took place during the early hours of the morning, as the Bharani star was rising in Pattamadai village in Tirunelveli district, Tamil Nadu. His father, P.S. Vengu Iyer, worked as a revenue officer and was a devotee of Shiva. His mother, Parvati Ammal, was also religious. Kuppuswami was the third and last child of his parents.[7][8]

As a child, he was very active and promising in academics and gymnastics. He attended medical school in Tanjore, where he excelled. He ran a medical journal called Ambrosia during this period. Upon graduation, he practiced medicine and worked as a doctor in British Malaya for ten years, with a reputation for providing free treatment to poor patients. Over time, a feeling developed in Dr. Kuppuswami that medicine was healing only on a superficial level, urging him to look elsewhere to fill the void, and in 1923 he left Malaya and returned to India to pursue his spiritual quest.[7]

Initiation

[edit]Upon his return to India in 1924, he went to Rishikesh where he met his guru, Vishvananda Saraswati, who initiated him into the Sannyasa order and gave him his monastic name. The full ceremony was conducted by Vishnudevananda, the mahant (abbot) of Sri Kailas Ashram.[7] Sivananda settled in Rishikesh and immersed himself in intense spiritual practices. Sivānanda performed austerities for many years while continuing to nurse the sick. In 1927, with some money from an insurance policy, he ran a charitable dispensary at Lakshman Jhula.[7]

-

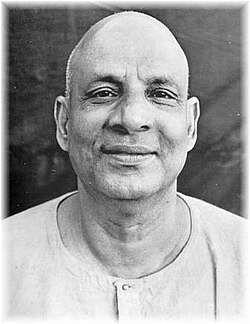

Krishnananda and Sivananda (right), c. 1945

-

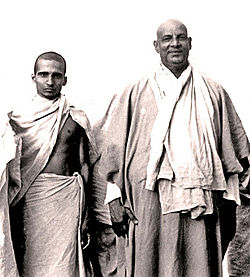

Sivananda and Vishnudevananda by the Ganges, c. 1950

-

Sivananda on a 1986 stamp of India

Founding the Divine Life Society

[edit]Sivananda founded the Divine Life Society in 1936 on the banks of the Ganges River, distributing spiritual literature for free.[7] Early disciples included Satyananda Saraswati, founder of Satyananda Yoga.[9][10]

In 1945, he created the Sivananda Ayurvedic Pharmacy, and organised the All-world Religions Federation.[7] He established the All-world Sadhus Federation in 1947 and the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy in 1948.[7] He called his yoga the Yoga of Synthesis, combining the Four Yogas of Hinduism (Karma Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, Jnana Yoga, Rāja Yoga), for action, devotion, knowledge, and meditation respectively.[11]

Sivananda travelled extensively on a major tour in 1950, and set up branches of the Divine Life Society throughout India. He vigorously promoted and disseminated his vision of yoga, adopting modern techniques to such an extent that he gained the nickname 'Swami Propagandananda'.[12][13] His Belgian devotee André Van Lysebeth wrote that his critics "disapproved of both his modern methods of diffusion and his propagation of yoga on such a grand scale to the general public", explaining that Sivananda was advocating a practice that everybody could do, combining "some asanas, a little pranayama, a little meditation and bhakti; well, a little of everything".[12][13]

The 9th All-India Divine Life Convention was held at Venkatagiri on March 16, 1957, which was presided by Sathya Sai Baba and attended by Satchidananda Saraswati and Swami Sadananda.[14]

Vegetarianism

[edit]Sivananda insisted on a strict lacto-vegetarian diet for moral and spiritual reasons, arguing that "meat-eating is highly deleterious to health".[15][16][17][18] Divine Life Society thus advocates a vegetarian diet.[18]

Mahasamadhi

[edit]Swami Sivananda died, described as entering Mahasamadhi, on 14 July 1963 beside the River Ganges at his Sivananda Ashram near Muni Ki Reti.[1]

Works

[edit]Sivananda wrote over 200 books on yoga.[19] Many of them are available free on the Divine Life Society's website.[20]

- Yogic Home Exercises. Easy Course of Physical Culture for Men & Women, Bombay, Taraporevala Sons & Co, 1944.

- Siva-Gita: an epistolary autobiography. The Sivananda Publication League. 1946.

- Principal Upanishads: with text, meaning notes and commentary. Yoga Vedanta Forest University, Divine Life Society. 1950.

- Raja Yoga: theory and practice. Yoga Vedanta Forest University, Divine Life Society. 1950.

- Inspiring songs and kirtans. Yoga-Vedanta Forest University. 1953.

- Music as yoga. The Yoga-Vedanta Forest University for the Sivananda Mahasamsthanam. 1956.

- Yoga of synthesis. Yoga-Vedanta Forest University. 1956.

- Story of my tour. Yoga-Vedanta Forest University. 1957.

- Sivananda-Kumudini Devi (1960). Sivananda's letters ro Sivananda-Kumudini Devi. Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy.

- India (1962). Lord Siva and his worship. Yoga-Vedanta forest academy, Divine life Society.

- Yoga practice, for developing and increasing physical, mental and spiritual powers. D.B. Taraporevala Sons. 1966.

- Fourteen lessons in raja yoga. Divine Life Society. 1970.

- Inspiring songs and sayings. The Divine Life Society. 1970.

- Yoga Vedanta dictionary. Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy. 1970.

- Kundalini yoga. Divine Life Society. 1971.

- The science of pranayama. Divine Life Society. 1971.

- Ten upanishads: with notes and commentary 8th ed. Divine Life Society. 1973.

- Sivananda vani: the cream of Sri Swami Sivananda's immortal, practical instructions on the yoga of synthesis in his own handwriting. Divine Life Society. 1978 [1957].

- Practice of yoga. The Divine Life Society. 1979.

- Autobiography of Swami Sivananda. Divine Life Society. 1980.

- Japa Yoga: a comprehensive treatise on mantra-sastra. Divine Life Society. 1981.

- Science of Yoga: Raja yoga; Jnana yoga; Concentration and meditation. Divine Life Society. 1981. ISBN 978-1465479358.

- Moksha gita. Divine Life Society. 1982 [1949].

- Samadhi yoga. The Divine Life Society. 1983.

- Yoga samhita. Divine Life Society. 1984.

- The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad: Sanskrit text, English translation, and commentary. Divine Life Society. 1985.

- Karma yoga. Divine Life Society. 1985. ISBN 978-0-949027-05-4.

- Bhakti yoga. Divine Life Society, Fremantle Branch. 1 January 1987. ISBN 978-0-949027-08-5.

- Lord Shanmukha and his worship. Divine Life Society. 1996. ISBN 978-81-7052-115-0.

- Raja Yoga. Kessinger Publishing. December 2005. ISBN 978-1-4253-5982-9.

- Life and Works of Swami Sivananda, by Sivānanda, Divine Life Society (W.A.). Fremantle Branch. Published by Divine Life Society, Fremantle Branch, 1985. ISBN 0-949027-04-9

- All About Hinduism

- Amrita Gita

- Bhagavad Gita (transliterated and translated by Sivananda, with chapter summaries)

- Brahma Sutras, 1949

- Conquest of Anger

- Conquest of Fear

- Easy Steps to Yoga

- Essence of Yoga

- God Exists

- A Great Guru and His Ideal Disciple (letters from Sivananda to Prananvananda)

- Guru-Bhakti Yoga

- Guru Tattva

- Gyana Jyoti, Wisdom Light, 1950

- Hindu Fasts & Festivals

- How to Become Rich, 1950

- How to Get Vairagya (Dispassion)

- Ideal of Married Life

- Karmas and Diseases

- Kingly Science Kingly Secret

- Life and Teachings of Lord Jesus

- Life and Teachings of Swami Sivananda, 1964

- Light, Power and Wisdom

- Lord Krishna, His Lilas and Teachings

- The Master Said... (1954 speech)

- May I Answer That?

- Mind, its Mysteries and Control, 1946

- Parables of Sivananda, 1955

- The Philosophy and Significance of Idol Worship

- Philosophy of Dreams

- Practical Ayurveda.

- Practical Lessons in Yoga

- Radio Talks, 1951

- Saints and Sages, 1951

- Satsanga and Svadhyaya

- Sayings of Swami Sivananda, 1947

- Self-Knowledge

- Sivananda Upanishad. A universal scripture in the Sage's own handwriting, (Vishnudevananda (ed.)) 1955

- Sixty-Three Nayanar Saints

- Swami Sivananda. His Life, Mission and Message, in pictures, 1953

- Temples in India

- Thought Power

- Thus Awakens Swami Sivananda

- Thus Inspires Swami Sivananda, 1962

- Thus Spake Sivananda

- Vedanta for Beginners

- Waves of Bliss, 1949

- What Becomes of the Soul After Death, 1950

- Yoga in Daily Life

- Yoga: Your Home Practice Companion. DK Publishing, 2018

Disciples

[edit]Sivananda's two chief acting organizational disciples were Chidananda Saraswati and Krishnananda Saraswati. Chidananda Saraswati was appointed president of the DLS by Sivananda in 1963 and served in this capacity until his death in 2008. Krishnananda Saraswati was appointed General Secretary by Sivananda in 1958 and served in this capacity until his death in 2001.

Disciples who went on to grow new organisations include:

- Chinmayananda Saraswati, founder of the Chinmaya Mission[21]

- Jyotirmayananda Saraswati, founder of Yoga Research Foundation, Miami, Florida, USA[22]

- Sahajananda Saraswati, Spiritual Head of Divine Life Society of South Africa[citation needed]

- Satchidananda Saraswati, founder of the Integral Yoga Institutes, around the world[23]

- Satyananda Saraswati, founder of Bihar School of Yoga[9]

- Sivananda Radha Saraswati, founder of Yasodhara Ashram, British Columbia, Canada[24]

- Venkatesananda Saraswati, inspirer of Ananda Kutir Ashrama in South Africa and Sivananda Ashram in Fremantle, Australia[citation needed]

- Vishnudevananda Saraswati, founder of the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ananthanarayan, Sri N. (1965). I Live to Serve – A Promise and A Fulfilment (PDF). Sivanandanagar, Tehri-Garhwal, U.A. India: Divine Life Society.

Intimate Glimpses into Gurudev Sivananda's Last Days Ë How the Holy Master Lived a Life of Unremitting Service to the Very End

- ^ Chetan, Mahesh (5 March 2017). "10 Most Inspiring Yoga Gurus of India". Indian Yoga Association. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Divine Life Society Britannica.com

- ^ McKean, Lise (1996). Divine enterprise: gurus and the Hindu Nationalist Movement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-226-56009-0. OCLC 32859823.

- ^ Morris, Brian (2006). Religion and anthropology: a critical introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-521-85241-8. OCLC 252536951.

- ^ "His Holiness Sri Swami Sivananda Saraswati Maharaj". Divine Life Society. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "H. H. Sri Swami Sivananda Saraswati". Divine Life Society. 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Swami Sivananda". Yoga Magazine (issue 18). February 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ a b Melton, J. Gordon (2010). "International Yoga Fellowship Movement". In Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (eds.). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). ABC-Clio. p. 1483. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

- ^ Aveling, Harry (1994). The Laughing Swamis: Australian Sannyasin Disciples of Swami Satyananda Saraswati and Osho Rajneesh. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 61. ISBN 978-8-12081-118-8.

- ^ Sivananda (29 May 2017). "Yoga of Synthesis".

- ^ a b Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga: the history of an embodied spiritual practice. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions. pp. 326–335. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5. OCLC 926062252.

- ^ a b Van Lysebeth, André (1981). "The Yogic Dynamo". Yoga (September 1981).

- ^ "8. From Cape to Kilanmarg". Sri Sathya Sai Speaks. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- ^ Rosen, Steven. (2011). Food for the Soul: Vegetarianism and Yoga Traditions. Praeger. p. 22. ISBN 978-0313397035

- ^ McGonigle, Andrew; Huy, Matthew. (2022). The Physiology of Yoga. Human Kinetics. p. 169. ISBN 978-1492599838

- ^ "Meat-Eating". sivanandaonline.org. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Vegetarianism". dlshq.org. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Swami Sivananda". Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- ^ "Download Books". The Divine Life Society. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- ^ "Chinmayananda: Indian spiritual thinker". www.britannica.com. 4 May 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "His Holiness Sri Swami Jyotirmayananda Saraswati Maharaj – The Divine Life Society". Retrieved 3 June 2024.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (21 August 2002). "Swami Satchidananda, Woodstock's Guru, Dies at 87". The New York Times.

- ^ Gates, Janice (2006). Yogini: Women Visionaries of the Yoga World. Mandala. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-1932771886.

- ^ Krishna, Gopala (1995). The Yogi: Portraits of Swami Vishnu-devananda. Yes International Publishers. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-936663-12-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Fornaro, Robert John (1969) Sivananda and the Divine Life Society: A Paradigm of the "secularism," "puritanism" and "cultural Dissimulation" of a Neo-Hindu Religious Society. Syracuse University.

- Ananthanarayanan, N. (1970) From Man to God-man: the inspiring life-story of Swami Sivananda, Indian Publ. Trading Corp.

- Gyan, Satish Chandra (1979) Swami Sivananda and the Divine Life Society: An Illustration of Revitalization Movement.

- Swami Venkatesānanda (1985) Sivananda: Biography of a Modern Sage Archived 27 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Divine Life Society. ISBN 0-949027-01-4

External links

[edit]Sivananda Saraswati

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Family Background

Sivananda Saraswati was born as Kuppuswami on September 8, 1887, in the small village of Pattamadai in the Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu, India, during the early hours of the morning under the ascendant star Bharani.[5] He was the third and youngest son of P. S. Vengu Iyer and Srimati Parvati Ammal, both of whom came from an orthodox Brahmin family with deep roots in Hindu traditions.[7] His father, Vengu Iyer, served as a tahsildar—a revenue inspector—for the Ettiapuram Estate and was a devout Hindu known for his regular ceremonial worship and virtuous life; he traced his ancestry to the renowned 16th-century philosopher and saint Appayya Dikshitar.[8] Vengu Iyer's piety created a home environment filled with daily rituals, which young Kuppuswami actively participated in by assisting his father. His mother, Parvati Ammal, was equally pious and played a key role in nurturing his initial spiritual sensitivities through her own religious devotion and emphasis on selfless service.[9] Raised in this spiritually charged atmosphere, Kuppuswami experienced the vibrant traditions of Hinduism from an early age, including participation in local Hindu festivals, frequent visits to nearby temples, and introductory lessons in Sanskrit to understand basic scriptural concepts.[9] These exposures instilled a sense of reverence for divine forms and cultural heritage. Early indicators of his spiritual disposition appeared in his selfless nature—such as sharing treats with friends—and his budding devotion to Lord Krishna, whom he adored through singing bhajans and enacting playful scenes from Krishna's lilas inspired by the Bhagavata Purana.[9]Education and Medical Career

Sivananda Saraswati, born Kuppuswamy, received his early education at the Rajah's High School in Ettayapuram, Tamil Nadu, where he consistently excelled academically, topping his class and earning prizes annually for his outstanding performance.[5] He demonstrated remarkable talents beyond studies, including proficiency in singing, debating, and sports, while also engaging in social service activities such as lecturing on epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata to fellow students.[5] After completing his First Arts Examination with distinction from Madras University, he pursued medical studies at the Medical School in Tanjore, where his commitment to service continued; he organized medical conferences and launched a journal titled Ambrosia to disseminate health knowledge.[5] Kuppuswamy graduated with flying colors in 1913, earning recognition as a gold medalist and the title of "Doctor."[5] Following his graduation, Kuppuswamy embarked on a professional career as a medical officer in British Malaya (present-day Malaysia), serving from 1913 to 1923 in the government's medical department, primarily at rubber estates.[10] In this role, he provided extensive care to plantation workers, including native laborers and coolies, often treating them free of charge despite the demanding conditions.[5] His duties frequently involved combating outbreaks, such as plague epidemics, requiring him to travel across estates and confront widespread human suffering, from physical ailments to socioeconomic hardships among the impoverished communities.[5] These experiences profoundly impacted him, exposing the limitations of material pursuits and igniting an inner quest for deeper meaning, leading him to study philosophy, adopt vegetarianism, and incorporate yoga practices into his routine.[11] By 1923, persistent health issues, including rheumatism contracted during his rigorous work, combined with an intensifying spiritual aspiration, prompted Kuppuswamy to resign from his position and return to India.[5] This transition marked the culmination of his secular career, as the stark realities of suffering he witnessed abroad fostered a growing detachment from worldly ambitions and a turn toward spiritual exploration.[12]Spiritual Initiation

Renunciation and Sannyasa

In 1924, Kuppuswami Iyer, disillusioned with his medical career despite its successes, felt an irresistible pull toward spiritual renunciation. After returning to India from British Malaya, he undertook a pilgrimage to holy sites including Varanasi, Nasik, and others, before arriving in Rishikesh.[13][1] There, he encountered Swami Vishwananda Saraswati, a revered monk from the Sringeri Math, who provided initial spiritual guidance and discerned his readiness for monastic life.[9] This meeting marked a turning point, inspiring Iyer to fully commit to sannyasa. On June 1, 1924, at Swarg Ashram in Rishikesh on the banks of the Ganga, Swami Vishwananda formally initiated him into the Dashnami Sannyasa order of Adi Shankaracharya through the sacred Viraja Homa ritual.[13] Upon initiation, he adopted the monastic name Swami Sivananda Saraswati, symbolizing his new identity as a renunciate in the Saraswati branch of the order.[9] The guru's brief but profound interaction—lasting only a day—imparted essential instructions on austerity and devotion, after which Swami Vishwananda departed, leaving the new sannyasin to pursue his path independently.[14] With this initiation, Swami Sivananda completely renounced his professional life, distributing his remaining possessions and wealth to the needy, and embraced the rigorous ascetic lifestyle of a wandering monk.[13] He discarded all worldly attachments, including clothing and belongings, accepting only an ochre robe, and sustained himself through madhukari—the traditional practice of begging alms from seven households daily to maintain humility and detachment.[15] This mendicant existence, free from material dependencies, allowed him to focus entirely on inner transformation amid the Himalayan solitude. In the years immediately following his sannyasa, Swami Sivananda immersed himself in intense sadhana along the banks of the Ganga and in remote Himalayan retreats.[9] His daily routine centered on japa (repetitive chanting of divine names, particularly "Om Namo Bhagavate Vasudevaya"), prolonged meditation on the Supreme Reality, and selfless service to passing sadhus, pilgrims, and the infirm, whom he assisted with medical knowledge from his past life without seeking reward.[13] These practices, conducted in silence and seclusion, cultivated profound spiritual experiences, purifying his mind and fostering a state of egoless devotion.[16]Settlement in Rishikesh

In 1924, Swami Sivananda Saraswati arrived in Rishikesh on May 8, drawn to the Himalayan foothills for deeper spiritual pursuit after his renunciation. He settled at Swargashram, a modest colony of huts on the right bank of the Ganges River, embracing a life of simplicity in a small kutir that served as his initial abode.[5] There, he immersed himself in austere living, focusing on self-discipline and detachment from worldly comforts amid the serene yet challenging environment of the sacred site.[9] Initially adopting the role of a wandering monk, Sivananda roamed the vicinity, practicing intense tapasya and engaging in solitary reflection before gradually anchoring himself at Swargashram. His daily routine was marked by rigorous discipline: rising at 4 a.m. to plunge into the icy Ganges for japa and kirtan while standing waist-deep in the waters, followed by extended periods of meditation exceeding twelve hours daily.[9] He balanced this with acts of service, visiting the huts of the sick in Swargashram to provide free medical aid using his prior knowledge as a physician, and teaching small groups of spiritual seekers through informal sessions on devotion and self-realization. Over time, he expanded his kutir to accommodate a growing number of disciples who sought his guidance, transforming it into a nascent center for spiritual instruction.[5] Sivananda's encounters with local sadhus enriched his practice and broadened his influence; he frequently interacted with these ascetics, exchanging insights on yogic disciplines and scriptural wisdom during communal gatherings. These interactions led to the early dissemination of his knowledge through heartfelt talks, where he expounded on the lives of saints and core principles of yoga, attracting earnest aspirants to his humble setup and laying the groundwork for communal spiritual life in Rishikesh.[5]Teachings and Philosophy

Core Spiritual Principles

Swami Sivananda Saraswati's spiritual philosophy was firmly rooted in Advaita Vedanta, the non-dualistic school of thought that posits the ultimate reality as Brahman, an undivided consciousness underlying all existence, with the individual self (Atman) being identical to this universal essence. He emphasized self-realization as the supreme goal, achieved through the dissolution of the ego, which he described as the false sense of separateness that veils true knowledge. This realization, according to Sivananda, liberates the seeker from illusion (maya) and reveals the oneness of all life, integrating profound metaphysical insight with everyday ethical conduct.[17] Central to his teachings were the four classical paths of yoga, which he advocated as complementary approaches suitable to different temperaments, ultimately converging toward the same divine realization. Jnana Yoga, the path of knowledge, involves intellectual inquiry into the nature of the self through study of scriptures like the Upanishads and discrimination between the real and unreal, leading to direct intuitive apprehension of non-duality. Bhakti Yoga, the path of devotion, fosters surrender to the divine through love, prayer, and worship, transcending personal ego by seeing God in all beings. Karma Yoga, the path of selfless action, teaches performing duties without attachment to results, purifying the heart and mind while serving humanity as an expression of divine will. Raja Yoga, the path of meditation, employs concentration and control of the mind to attain inner stillness and union with the infinite, as outlined in Patanjali's Yoga Sutras. Sivananda's integral yoga synthesized these paths, urging practitioners to balance action, devotion, knowledge, and meditation for holistic spiritual growth.[18] A hallmark of Sivananda's philosophy was the oneness of all religions, viewing them as diverse rivers flowing to the same ocean of truth, with non-essential differences arising from cultural contexts rather than core principles. He proclaimed, "All religions are one. They teach a divine life," and respected prophets and saints across faiths, encouraging followers to practice their own religion sincerely while embracing universal love and service. This inclusive vision rejected sectarianism, promoting a practical spirituality accessible to all without barriers of caste, creed, or ritualistic formalism, which he criticized as outdated social constructs hindering true devotion. His motto, "Serve, Love, Give, Purify, Meditate, Realize", encapsulated this approach: serving others dissolves ego, love cultivates devotion, giving fosters detachment, purification prepares the mind, meditation deepens insight, and realization attains liberation.[19][20][21] Sivananda strongly advocated vegetarianism as an essential ethical and spiritual discipline, intrinsically linked to ahimsa (non-violence), which he regarded as the foundation of all yogic practices. He taught that abstaining from meat purifies the body and mind, preventing the influx of tamasic (dull) qualities that obstruct spiritual progress, and aligns the practitioner with compassion for all sentient beings as manifestations of the divine. "The first step in spiritual advancement is the giving up of meat diet," he stated, emphasizing that such a sattvic (pure) diet enhances clarity for meditation and self-realization while embodying non-violence in daily life. This principle extended his Advaita teachings into practical ethics, making spirituality a lived reality rather than abstract doctrine.[22]Yoga System and Practices

His teachings inspired the development of a holistic yoga system known as Sivananda Yoga, which integrates physical postures (asanas), breathing exercises (pranayama), and purification techniques (kriyas) to promote overall health and spiritual growth. This approach emphasizes balanced practice to cultivate physical vitality, mental clarity, and inner peace, drawing from classical Hatha Yoga traditions while making them accessible to modern practitioners. The system is structured around the Five Points of Yoga—Proper Exercise (asanas), Proper Breathing (pranayama), Proper Relaxation, Proper Diet, and Positive Thinking with Meditation—which provide a comprehensive framework for integral spiritual development.[23][24] Central to Sivananda Yoga is a sequence of 12 basic asanas designed to exercise every major part of the body, targeting flexibility, strength, balance, and the stimulation of energy centers (chakras). These include Sirsasana (headstand) for brain nourishment, Sarvangasana (shoulderstand) for thyroid stimulation, Halasana (plough) for spinal health, Matsyasana (fish) for throat opening, Paschimottanasana (seated forward bend) for hamstring and back stretching, Bhujangasana (cobra) for abdominal toning, Salabhasana (locust) for lower back strengthening, Dhanurasana (bow) for full spine activation, Ardha Matsyendrasana (half spinal twist) for detoxification, Kakasana (crow) for arm balance, Padahastasana (standing forward bend) for leg and spine elongation, and Trikonasana (triangle) for side stretching and balance. Performed in a specific order, these asanas are intended to open energy channels, remove blockages, and foster holistic well-being when practiced regularly under guidance. Pranayama techniques, such as Kapalabhati (skull shining breath) for lung purification and Anulom Vilom (alternate nostril breathing) for nervous system balance, complement the asanas by regulating prana (life force), while kriyas like Neti (nasal cleansing) and Dhauti (digestive tract purification) from the shatkarmas support internal cleansing to enhance the efficacy of the entire system.[23][25][26] As a foundation for these physical and meditative practices, Sivananda stressed ethical and lifestyle preparations encapsulated in his motto "Serve, Love, Give," which encourages selfless service, universal love, and generosity to purify the mind and heart before advancing into yoga techniques. He advocated a sattvic diet—consisting of fresh fruits, vegetables, grains, and dairy—to promote mental purity and sustain energy for practice, while avoiding stimulating or heavy foods that could disturb equilibrium. Celibacy (brahmacharya), or conservation of vital energy through moderated or abstinent sexual life, was deemed essential for amplifying willpower, memory, and spiritual progress, as it prevents dissipation of ojas (vital essence) needed for higher yoga attainments.[27][28][29] In his teachings on kundalini awakening, Sivananda emphasized a gradual, balanced approach through integrated asana, pranayama, and meditation, warning against forceful methods that could lead to physical or mental imbalance. He described kundalini as dormant cosmic energy at the base of the spine, which rises safely along the sushumna nadi (central channel) when supported by ethical living and steady sadhana, ultimately leading to self-realization without extremes. This practical framework, rooted in Vedantic non-dualism, simplified ancient texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika for laypeople by distilling complex rituals into daily routines adaptable to contemporary life. Sivananda's system significantly influenced modern Hatha Yoga by prioritizing accessibility and integration over esoteric complexity, inspiring global teachers to adopt simplified sequences that democratized yoga for health and spirituality rather than elite asceticism alone.[30][31]Divine Life Society

Founding and Organizational Growth

Swami Sivananda Saraswati founded the Divine Life Society in 1936 in Rishikesh, India, beginning with a small, dilapidated kutir on the banks of the Ganges River as a center for spiritual dissemination and selfless service.[5] The organization was registered as a trust that same year, with its primary objectives centered on spreading spiritual knowledge through teachings on yoga, Vedanta, and divine life practices to uplift humanity.[5] From these humble origins, the Society rapidly expanded under Sivananda's guidance, evolving into a global network that attracted seekers from diverse backgrounds and established branches across India and beyond.[32] Sivananda played a pivotal role in directing the Society's organizational growth, overseeing the launch of key initiatives that fueled its development. He initiated the monthly journal The Divine Life in September 1938 to propagate his teachings widely, and later established the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy Press in 1951 to handle the increasing volume of publications, which eventually numbered over 300 books on spiritual topics.[5] Additionally, he organized extensive tours, including a major All-India and Ceylon tour in 1950 that inspired the creation of numerous branches throughout the country and stirred a nationwide spiritual awakening.[32] To foster deeper training, Sivananda founded the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy in 1948, which served as a hub for intensive spiritual camps and programs aimed at practical sadhana.[5] The Society's international outreach began gaining momentum in the 1950s, marked by events like the World Parliament of Religions convened by Sivananda in 1953 at Sivanandashram, which drew participants from various faiths and laid groundwork for global expansion.[5] By the time of Sivananda's passing in 1963, the Divine Life Society had grown into a robust international entity with branches and members worldwide, continuing to expand thereafter under his successors while maintaining its core mission.[32]Key Activities and Institutions

Under the aegis of the Divine Life Society, Swami Sivananda Saraswati established the Sivananda Ashram in 1936 at Muni Ki Reti, Rishikesh, as the headquarters and a central spiritual retreat for seekers, pilgrims, and residents pursuing yoga and Vedanta practices.[33] This ashram evolved into a multifaceted hub integrating spiritual training, selfless service, and cultural preservation, accommodating hundreds of visitors annually while fostering an environment for meditation and self-discipline.[34] In 1948, Sivananda founded the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy as a dedicated department of the Society to provide systematic instruction in yoga, Vedanta, and Indian spiritual traditions, with regular classes commencing on July 3 of that year to train both resident aspirants and external participants.[35] Complementing these efforts, the Society's publications wing, known as the Sivananda Publication League, was developed to disseminate Sivananda's teachings globally, producing over 300 books authored by him on yoga, Vedanta, health, and spirituality, alongside monthly periodicals in English and Hindi distributed free or at nominal cost.[32] Key activities included the Annual Sadhana Weeks, intensive spiritual camps held at the ashram during Sivananda's lifetime and continuing thereafter, drawing hundreds for immersive sessions on meditation, yoga, and ethical living to promote personal rejuvenation.[33] Sivananda personally undertook extensive spiritual tours, notably a major 1950 journey across India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), where he delivered discourses on universal peace and Hindu philosophy, igniting widespread spiritual interest and establishing numerous Society branches.[32] To advance integrated health, the Society operated free medical dispensaries through the Sivananda Charitable Hospital, offering year-round treatment to the public, including periodical relief camps and specialized leprosy care for approximately 200 patients, beginning as a modest clinic in the ashram.[33] The Divine Life Society expanded internationally with branches in India and abroad, including the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centers, which replicate core programs in yoga instruction and spiritual education across multiple countries.[32] Humanitarian initiatives emphasized women's education and support for vulnerable groups, providing free schooling and facilities to around 1,000 underprivileged students from primary to postgraduate levels, with dedicated efforts like the Sivananda Homes for orphaned and needy children, including an all-girls facility managed by the Society's trustees.[33] Additional welfare programs encompassed the Annapurna Annakshetra, a daily free meal service feeding about 600 individuals, alongside broader relief work for disaster-affected communities and the elderly.[33] Environmental stewardship was reflected in the ashram's forested setting, which Sivananda preserved as a sacred space for spiritual practice, though specific conservation projects were integrated into the Society's service-oriented ethos rather than standalone initiatives.[34]Literary Works

Major Publications

Swami Sivananda Saraswati authored more than 200 books on subjects ranging from yoga practices to Vedanta philosophy and spiritual ethics, all disseminated primarily through the Divine Life Society Press established after the society's founding in 1936. Many of these works are compilations of his lectures, articles, and letters compiled by disciples and the Divine Life Society.[36] His literary output began in the late 1920s with handwritten notes and articles shared among spiritual seekers in Rishikesh, transitioning to formal printed publications by 1929.[37] These works, characterized by straightforward prose, aimed to render ancient Indian spiritual wisdom accessible to lay readers worldwide, emphasizing practical application over esoteric theory.[38] The early books focused on the integral paths of yoga, with subsequent volumes expanding into comprehensive treatises on devotion, knowledge, and selfless service. Many have been translated into over a dozen languages, including Hindi, Tamil, German, French, and Spanish, facilitating their distribution through Divine Life Society branches globally.[39] Below is a selection of his major publications, highlighting key titles with brief synopses of their content and significance in his oeuvre:- Practice of Yoga (1929): Sivananda's inaugural printed book, introducing the foundational principles and techniques of yoga for beginners, marking the start of his systematic dissemination of yogic science.[40]

- Practice of Karma Yoga (1930): Explores selfless action as a path to spiritual liberation, detailing how daily duties can be transformed into divine service without attachment to results.[18]

- Practice of Bhakti Yoga (1931): Outlines devotion to God through prayer, chanting, and surrender, presenting bhakti as an accessible route to divine union for householders and ascetics alike.

- Practice of Jnana Yoga (1932): Discusses the path of knowledge and self-inquiry, drawing on Advaita Vedanta to guide readers toward realizing the non-dual nature of reality.

- Practice of Raja Yoga (1933): A guide to Patanjali's Yoga Sutras, covering meditation, concentration, and ethical restraints to achieve mental mastery and samadhi.

- Bliss Divine (1937): A collection of essays on the purpose of human life, blending philosophy, ethics, and practical spirituality to inspire inner peace and divine realization.[41]

- Kundalini Yoga (1939, compiled edition): Describes the awakening of spiritual energy through chakras and pranayama, cautioning on safe practices while elucidating esoteric aspects of tantric yoga.

- All About Hinduism (1947): An encyclopedic overview of Hindu scriptures, rituals, deities, and sects, serving as an introductory text to foster interfaith understanding and cultural preservation.

- The Science of Pranayama (1950, compiled): Systematically explains breath control techniques, their physiological and spiritual benefits, and integration with asanas for health and enlightenment.