Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

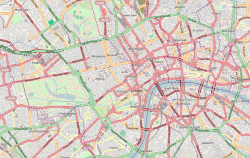

Sloane Square

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Sloane Square is a small hard-landscaped square on the boundaries of the central London[1] districts of Belgravia and Chelsea, located 1.8 miles (2.9 km) southwest of Charing Cross, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The area forms a boundary between the two largest aristocratic estates in London, the Grosvenor Estate and the Cadogan.[2][n 1] The square was formerly known as 'Hans Town', laid out in 1771 to a plan of by Henry Holland Snr. and Henry Holland Jnr. Both the square and Hans Town were named after Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), an Anglo-Irish doctor who, jointly with his appointed trustees, owned the land at the time.[3]

Location

[edit]The bulk of Chelsea, especially the east end more local to Sloane Square, is architecturally and economically similar to South Kensington, Belgravia, St James's, and Mayfair. The largely retail at ground floor Kings Road with its design and interior furnishing focus intersects at Sloane Square the residential, neatly corniced and dressed façades of Sloane Street leading from the Victoria Embankment promenade to the small district of Knightsbridge. On the northern side of the square is the Sloane Square Hotel.

- Exclusive housing hub

Estates on all sides are made up of ornate, luxuriously furnished private apartments set behind railings — a minority of these remain combined to form large townhouses, primarily in amongst those of rows of not more than four storeys. Gothic, classical and Edwardian architecture mix; the area has grown piecemeal, including in infill, under strict character and aesthetic demands of local urban planning. Elements of almost every street were reinstated, in similar style, after the London Blitz.

- Social analysis

In sociology, a small social class of London has since the 1980s been cast and to some extent outcast as Sloane Rangers or Sloanies, relatively young, underemployed and ostentatiously well-off members of the upper classes who linguistically have their own evolving lexicon, sloane(y) speak, spoken in received pronunciation. Some are heavily engaged investors in charities, new businesses and the arts, particularly with the influx of and integration with young, wealthy, foreign-born Chelsea residents. The endurance of this class is reflected in an occasional dramatic work or fly on the wall documentary such as Made in Chelsea.[4]

History

[edit]The square has two notable buildings. Peter Jones department store designed by Reginald Uren of the firm Slater Moberly and Uren in 1936 and now a Grade II* listed building on account of its early curtain wall and modernist aesthetic, pioneering in the UK for a department store.[5] The building was carefully restored 2003–2007 with internal upgrading in line with the original designs by John McAslan and Partners. This included making the three storey atrium full-height.[6] Peter Jones now operates as part of the employee-owned John Lewis chain.

The other is the Royal Court Theatre first opened in 1888 which has been important for avant-garde theatre since 1956 when it became the home of the English Stage Company.[7]

100m from the Square in Sloane Terrace, the former Christian Science Church[8] was built in 1907 and converted in 2002 for concert hall use as Cadogan Hall. It is now one of London's leading classical music venues.[9]

In 2005 revised landscaping of the square was proposed, involving a change to the road layout to make it more pedestrian friendly. One option was to create a central crossroads and two open spaces in front of Peter Jones and the Royal Court. The pedestrian area leading to Pavilion Road now houses the flagship stores of many luxury brands including Brora and Links of London. This option was put out to consultation, and the results in April 2007 showed that over 65% of respondents preferred a renovation of the existing square, so the crossroads plan has been shelved. Since then, independent proposals[10] have been put forward for the square.

A short walk down Kings Road from the Square is the National Army Museum.

Holy Trinity Sloane Street, the Church of England parish church of 1890 (50m north of the Square) is sometimes known as the "Cathedral of the Arts & Crafts Movement on account of its fine fittings. These include a complete set of windows by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, the most extensive he ever created.

Sloane Square Underground station (District and Circle lines) is at the south eastern corner of the square and the lines cross under the square to the north west. The River Westbourne is carried over the tube station platforms in plain view, in a circular iron aqueduct.

Fountain

[edit]

The Venus Fountain in the centre of the square was constructed in 1953, designed by sculptor Gilbert Ledward.[11][12][13] The fountain depicts Venus, and on the basin section of the fountain is a relief which depicts King Charles II and Nell Gwynn by the Thames,[13] which was used in relation to a house located close by that Nell Gwynn had used.[12]

In 2006, David Lammy put forward a proposal to have the fountain grade II listed,[12] which was successful.[13][14]

War memorial

[edit]

Also in the square, positioned slightly off-centre, is a stone cross that is known as Chelsea War Memorial. Made of Portland stone, and designed by an unknown architect, the cross has a capped head on a tapered shaft above a moulded three stage octagonal base. A large bronze sword is affixed to its west face. The cross is surmounted on a plinth which is inscribed with the following:

INVICTIS PAX

IN MEMORY OF THE

MEN AND WOMEN

OF CHELSEA

WHO GAVE

THEIR LIVES IN

THE GREAT WAR

MDCCCCXIV

MDCCCCVIII

AND

MCMXXXIX

MCMXLV

THEIR LIVES

FOR THEIR COUNTRY

THEIR SOULS TO THEIR GOD.

The monument has also been Grade II listed, since 2005.[15]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- References

- ^ "London's Places" (PDF). London Plan. Greater London Authority. 2011. p. 46. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Geograph:: Sloane Square [12 photos] in TQ2878". www.geograph.org.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ "Settlement and building: From 1680 to 1865, Hans Town: A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea". London: Victoria County History. 2004. pp. 47–51. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "OK, yo! Sloane-speak's gone street" The Daily Telegraph, Celia Walden. 17 July 2008

- ^ "PETER JONES STORE, Kensington and Chelsea - 1226626". Historic England. 7 November 1984. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Hunter, Will (April 2007). "Keeping up at Peter Jones | Features". www.building.co.uk. Building Magazine. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "ROYAL COURT THEATRE, Kensington and Chelsea - 1226628". Historic England. 28 June 1972. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "FIRST CHURCH OF CHRIST SCIENTIST, Kensington and Chelsea - 1226700". Historic England. 15 April 1969. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "Cadogan Hall". Archived from the original on 17 June 2012.

- ^ Richardbird.info, Independent proposal for improvement

- ^ "Sloane Square". www.gardenvisit.com. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ a b c "The Venus Fountain In Sloane Square Proposed For Listing". 27 July 2008. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008.

- ^ a b c 'Fountains of London' - Secret London

- ^ Historic England. "The Venus Fountain (1391739)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Sloane Square War Memorial (1391379)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- Notes

- ^ Emphasising their non-Anglo-Saxon surnames, these key longstanding freeholders of around Sloane Square have the counter-intuitive pronunciations /ˈɡroʊvənər/ GROH-vən-ər and /kəˈdʌɡən/ kə-DUG-ən.