Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stotra

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

Stotra (Sanskrit: स्तोत्र) is a Sanskrit word that means "ode, eulogy or a hymn of praise."[1][2] It is a literary genre of Indian religious texts designed to be melodically sung, in contrast to a shastra which is composed to be recited.[1] 'Stotra' derives from 'stu' meaning 'to praise' [3]

A stotra can be a prayer, a description, or a conversation, but always with a poetic structure. It may be a simple poem expressing praise and personal devotion to a deity for example, or poems with embedded spiritual and philosophical doctrines.[4]

A common feature of most stotras other than Nama stotras is the repetition of a line at the end of every verse. For example, the last line of every verse in the Mahiṣāsura Mardinī Stotra ends in "Jaya Jaya Hē Mahiṣāsura-mardini Ramyakapardini śailasute."

Many stotra hymns praise aspects of the divine, such as Devi, Shiva, or Vishnu. Relating to word "stuti", coming from the same Sanskrit root stu- ("to praise"), and basically both mean "praise". Notable stotras are Shiva Tandava Stotram in praise of Shiva and Rama Raksha Stotra, a prayer for protection to Rama.

Stotras are a type of popular devotional literature. Among the early texts with Stotras are by Kuresha,[clarification needed] which combine Ramanuja's Vedantic ideas on qualified monism about Atman and Brahman (ultimate, unchanging reality), with temple practices.[4] Stotras are key in Hindu rituals and blessings.[5]

Etymology and definition

[edit]Stotra comes from the Sanskrit root stu- which means "to praise, eulogize or laud" combined with the ṣṭran suffix.[4] Literally, the term refers to "poems of praise".[6] The earliest trace of stotras are Vedic, particularly in the Samaveda.[6]

The genre of stotras spans from refined, personal works of poetic phrase such as kavya to impersonal lists of a deity's names (nama-stotras) that can function like mantras through repetition. Historically linked to Vedic hymns and other lyrical poetry, stotras appear in many South Asian traditions, including Buddhism, Jainism, Shaivism, and Vaishnavism, and are often included in larger works like the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and various Puranas and Tantras.[7]

Example

[edit]

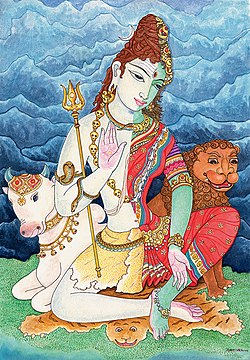

The following is a Peterson translation of a Stotra by the Tamil poet Appar for Ardhanarishvara, the Hindu concept of a god who incorporates both the masculine and the feminine as inseparable halves.[8]

An earring of bright new gold one ear,

a coiled conch shell sways on the other,

On one side he chants the Vedic melodies,

on the other, he gently smiles,

Matted hair adorned with sweet konrai blossoms on one half of his head,

and a woman's curls on the other, he comes.

The one the nature of his form, the other of hers,

And both are the very essence of his beauty.

— Appar, Ardhanarishvara Stotra, [8]

Nama-stotra

[edit]The nama-stotra is based on chanting a litany of names for a deity. The Sahasranama, a type of nama-stotra, is a litany of a thousand names for a particular deity. Sahasranama means "1000 names"; Sahasra means 1000 and nama means names. For example, Vishnu Sahasranama means 1000 names of Vishnu.[9] Other nama-stotras may include 100 or 108 epithets of the deity. According to Hinduism, the names of God are valuable tools for devotion.

Notable stotras

[edit]Stotras for Siva

[edit]- Śiva Tāṇḍava Stotra

- Śiva Mahimna Stotra

- Panchākṣara Stotra

- Nataraja Stotra

- Asitakṛtam Śivastotram

- Dakshinamūrti Stotra

Stotras for Devi

[edit]- Mahiṣāsura Mardinī Stotra

- Aṣṭalakshmī Stotra

- Agasti Lakshmi Stotra

- Annapūrṇa Stotra

- Radha Sahasranama Stotra[10][11]

- Lalita Sahasranama Stotra

- Bala Tripurasundari Sahasranama Stotra[12][13]

- Bhavani Sahasranama Stotra[14][15][16]

- Dakaradi Sridurga Sahasranama Stotra

- Durga Sahasranama Stotra[17]

- Gayathri Sahasranama Stotra[18]

- Kali Sahasranama Stotra[19][20]

- Kalika Sahasranama Stotra[21][22]

- Lalitarahasya Sahasranama Stotra

- Lakshmi Sahasranama Stotra[23][24]

- Minakshi Sahasranama Stotra

- Parvati Sahasranama Stotra[25][26]

- Saraswati Sahasranama Stotra[27][28][29]

- Sita Sahasranama Stotra[30][31]

- Sodasi Rajarajeswari Sahasranama Stotra[32]

- Syamala Sahasranama Stotra[33]

Stotras for Vishnu & avatara

[edit]- Hayagrīva Stotra

- Hari Stotra

- Vishnu Sahasranama Stotra

- Narasimha Kavacham Stotra

- Rāma Raksha Stotra

- Venkatesa Sahasranama Stotra

- Santanagopala Sahasranama Stotra

- Rakaradi Srirama Sahasranama Stotra

- Makaradi Srirama Sahasranama Stotra

- Lakshminarasimha Sahasranama Stotra

- Kakaradi Krishna Sahasranama Stotra

Stotras for other Gods & Goddesses

[edit]- Māruti Stotra

- Anjaneya Sahasranama Stotra[34]

- Surya Sahasranama Stotra[35][36]

- Sanaischara Sahasranama[37]

General / Philosophical Stotras

[edit]- Dvādaśa Stotra by Madhvacharya

- Mohamudgara Stotra (Bhaja Govindam) by Sankaracharya

Jainism

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Monier Williams, Monier Williams' Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Article on Stotra

- ^ Apte 1965, p. 1005.

- ^ "Stotra". Hindupedia, the Hindu Encyclopedia. 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2025-05-07.

- ^ a b c Nancy Ann Nayar (1992). Poetry as Theology: The Śrīvaiṣṇava Stotra in the Age of Rāmānuja. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. ix–xi. ISBN 978-3447032551.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (2024-09-20). "Stotra: Significance and symbolism". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 2025-05-07.

- ^ a b Nancy Ann Nayar (1992). Poetry as Theology: The Śrīvaiṣṇava Stotra in the Age of Rāmānuja. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-3447032551.

- ^ Stainton, Hamsa (2019). Poetry as prayer in the Sanskrit hymns of Kashmir. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-0-19-088982-1.

- ^ a b Ellen Goldberg (2012). Lord Who Is Half Woman, The: Ardhanarisvara in Indian and Feminist Perspective. State University of New York Press. pp. 91–96. ISBN 978-0791488850.

- ^ Vishnu Sahasranamam on Hindupedia, the Online Hindu Encyclopedia

- ^ Rita Thyagarajan, Sri Radha Sahasranama

- ^ Yaśodā Kumāra Dāsa, Sri Radha Sahasranama Stotram

- ^ https://stotranidhi.com/en/sri-bala-sahasranama-stotram-in-english/

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_2rAk3gBCA

- ^ Durga Lal Sharma Raj Purohit Kishtavad, Bhavani Sahasranama Stavaraj

- ^ Shri Bhavani Sahasra Nam Stotram,Chaukhamba Sanskrit Pratisthan, Delhi

- ^ Swami Nirdosha, Bhavani Sahasranama Stotram

- ^ Durga Sahasranama Stotram chanting in Sanskrit

- ^ Bengaluru Sister, Sri Gayathri Sahasranama

- ^ https://www.astromantra.com/kali-sahastranaam/?srsltid=AfmBOor4itdS10UECCOIfMIvPBCle2nRnV1H1o3L5docM4hmBTUen92f

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LauyKyOjeos

- ^ Stotranidhi.com

- ^ Kalika Sahasranama Stotra (From Kalika Kulasarvasva)

- ^ Lakshmi Sahasranama Stotram, translated by P.R.Ramachander

- ^ Lakshmi Sahasranama Stotram with lyrics

- ^ Shri Parvati Sahasranama Stotram in Sanskrit

- ^ Koushik K, Parvati Sahasranama from Kurma Purana

- ^ Sarasvati Sahasra Nama Stotram

- ^ Essence of Skanda Purana by Kamakoti Peetham

- ^ Prema Rangarajen, Saraswati Sahasranama Stotram

- ^ Prem Prakesh Dubey, Sri Sita Sahasranama Stotram

- ^ Anika Aggarwal, Sri Sita Sahasranama Stotram with lyrics

- ^ Shri Rajarajeswari Sahasranama Stotram chanting

- ^ Shri Syamala Sahasranama Chants by Dr.R.Thiagarajan

- ^ Tangirala Lakshmi Murty, Sri Hanuman, Anjaneya Sahasranamam

- ^ Rajalakshmee Sanjay, Surya Sahasranama

- ^ Surya Sahassthranaam by Rattan Mohan Sharma

- ^ Shri Sanaischara Sahasranama, Chants by Dr.R.Thiagarajan

Bibliography

[edit]- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965), The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (Fourth revised and enlarged ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-0567-4