Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

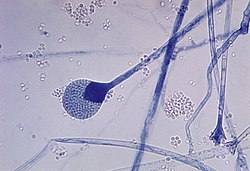

Sporangium

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

A sporangium (from Late Latin, from Ancient Greek σπορά (sporá) 'seed' and ἀγγεῖον (angeîon) 'vessel'; pl.: sporangia)[1] is an enclosure in which spores are formed.[2] It can be composed of a single cell or can be multicellular. Virtually all plants, fungi, and many other groups form sporangia at some point in their life cycle. Sporangia can produce spores by mitosis, but in land plants and many fungi, sporangia produce genetically distinct haploid spores by meiosis.

Fungi

[edit]

In some phyla of fungi, the sporangium plays a role in asexual reproduction, and may play an indirect role in sexual reproduction. The sporangium forms on the sporangiophore and contains haploid nuclei and cytoplasm.[3] Spores are formed in the sporangiophore by encasing each haploid nucleus and cytoplasm in a tough outer membrane. During asexual reproduction, these spores are dispersed via wind and germinate into haploid hyphae.[4]

Although sexual reproduction in fungi varies between phyla, for some fungi the sporangium plays an indirect role in sexual reproduction. For Zygomycota, sexual reproduction occurs when the haploid hyphae from two individuals join to form a zygosporangium in response to unfavorable conditions. The haploid nuclei within the zygosporangium then fuse into diploid nuclei.[5] When conditions improve, the zygosporangium germinates, undergoes meiosis and produces a sporangium, which releases spores.

Land plants

[edit]

In mosses, liverworts and hornworts, an unbranched sporophyte produces a single sporangium, which may be quite complex morphologically. Most non-vascular plants, as well as many lycophytes and most ferns,[clarification needed] are homosporous (only one kind of spore is produced). Some lycophytes, such as the Selaginellaceae and Isoetaceae,[7]: 7 the extinct Lepidodendrales,[8] and ferns, such as the Marsileaceae and Salviniaceae are heterosporous (two kinds of spores are produced).[7]: 18 These plants produce both microspores and megaspores, which give rise to gametophytes that are functionally male or female, respectively. Most heterosporous plants there are two kinds of sporangia, termed microsporangia and megasporangia.

Sporangia can be terminal (on the tips) or lateral (placed along the side) of stems or associated with leaves. In ferns, sporangia are typically found on the abaxial surface (underside) of the leaf and are densely aggregated into clusters called sori. Sori may be covered by a structure called an indusium. Some ferns have their sporangia scattered along reduced leaf segments or along (or just in from) the margin of the leaf. Lycophytes, in contrast, bear their sporangia on the adaxial surface (the upper side) of leaves or laterally on stems. Leaves that bear sporangia are called sporophylls. If the plant is heterosporous, the sporangia-bearing leaves are distinguished as either microsporophylls or megasporophylls. In seed plants, sporangia are typically located within strobili or flowers.

Cycads form their microsporangia on microsporophylls which are aggregated into strobili. Megasporangia are formed into ovules, which are borne on megasporophylls, which are aggregated into strobili on separate plants (all cycads are dioecious). Conifers typically bear their microsporangia on microsporophylls aggregated into papery pollen strobili, and the ovules, are located on modified stem axes forming compound ovuliferous cone scales. Flowering plants contain microsporangia in the anthers of stamens (typically four microsporangia per anther) and megasporangia inside ovules inside ovaries. In all seed plants, spores are produced by meiosis and develop into gametophytes while still inside the sporangium. The microspores become microgametophytes (pollen). The megaspores become megagametophytes (embryo sacs).[citation needed]

Eusporangia and leptosporangia

[edit]Categorized based on developmental sequence, eusporangia and leptosporangia are differentiated in the vascular plants.

- In a leptosporangium, found only in leptosporangiate ferns, development involves a single initial cell that becomes the stalk, wall, and spores within the sporangium. There are around 64 spores in a leptosporangium.

- In a eusporangium, characteristic of all other vascular plants and some primitive ferns, the initials are in a layer (i.e., more than one). A eusporangium is larger (hence contain more spores), and its wall is multi-layered. Although the wall may be stretched and damaged, resulting in only one cell-layer remaining.

Synangium

[edit]A cluster of sporangia that have become fused in development is called a synangium (pl. synangia). This structure is most prominent in Psilotum and Marattiaceae such as Christensenia, Danaea and Marattia.

Internal structures

[edit]A columella (pl. columellae) is a sterile (non-reproductive) structure that extends into and supports the sporangium of some species. In fungi, the columella, which may be branched or unbranched, may be of fungal or host origin. Secotium species have a simple, unbranched columella, while in Gymnoglossum species, the columella is branched. In some Geastrum species, the columella appears as an extension of the stalk into the spore mass (gleba).[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "sporangium". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020.

- ^ Rost, Thomas L.; et al. (2006). Plant Biology (2nd ed.). Thompson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 9780495013938.

- ^ "Fungi". Leaving Certificate Biology. 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Life History and Ecology of the Fungi". University of California Museum of Paleontology.

- ^ Webster, John; Weber, Roland (2007). Introduction to Fungi (3 ed.). Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80739-5. OCLC 74942051.

- ^ "Life Cycle of a Moss - Infographic". STEM Lounge. 2018-09-13. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- ^ a b Stace, C. A. (2019). New Flora of the British Isles (4th ed.). Middlewood Green, Suffolk, U.K.: C & M Logistics. ISBN 978-1-5272-2630-2.

- ^ Stewart, W.N.; Rothwell, G.W. (1993). Paleobotany and the Evolution of Plants (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38294-6.

- ^ Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi (10th ed.). Wallingford: CABI. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.