Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Thermionic emission

View on Wikipedia

Thermionic emission is the liberation of charged particles from a hot electrode whose thermal energy gives some particles enough kinetic energy to escape the material's surface. The particles, sometimes called thermions in early literature, are now known to be ions or electrons. Thermal electron emission specifically refers to emission of electrons and occurs when thermal energy overcomes the material's work function.

After emission, an opposite charge of equal magnitude to the emitted charge is initially left behind in the emitting region. But if the emitter is connected to a battery, that remaining charge is neutralized by charge supplied by the battery as particles are emitted, so the emitter will have the same charge it had before emission. This facilitates additional emission to sustain an electric current. Thomas Edison in 1880 while inventing his light bulb noticed this current, so subsequent scientists referred to the current as the Edison effect, though it wasn't until after the 1897 discovery of the electron that scientists understood that electrons were emitted and why.

Thermionic emission is crucial to the operation of a variety of electronic devices and can be used for electricity generation (such as thermionic converters and electrodynamic tethers) or cooling. Thermionic vacuum tubes emit electrons from a hot cathode into an enclosed vacuum and may steer those emitted electrons with applied voltage. The hot cathode can be a metal filament, a coated metal filament, or a separate structure of metal or carbides or borides of transition metals. Vacuum emission from metals tends to become significant only for temperatures over 1,000 K (730 °C; 1,340 °F). Charge flow increases dramatically with temperature.

The term thermionic emission is now also used to refer to any thermally-excited charge emission process, even when the charge is emitted from one solid-state region into another.

History

[edit]Because the electron was not identified as a separate physical particle until the work of J. J. Thomson in 1897, the word "electron" was not used when discussing experiments that took place before this date.

The phenomenon was initially reported in 1853 by Edmond Becquerel.[1][2][3] It was observed again in 1873 by Frederick Guthrie in Britain.[4][5] While doing work on charged objects, Guthrie discovered that a red-hot iron sphere with a negative charge would lose its charge (by somehow discharging it into air). He also found that this did not happen if the sphere had a positive charge.[6] Other early contributors included Johann Wilhelm Hittorf (1869–1883),[7][8][9][10][11][12] Eugen Goldstein (1885),[13] and Julius Elster and Hans Friedrich Geitel (1882–1889).[14][15][16][17][18]

Edison effect

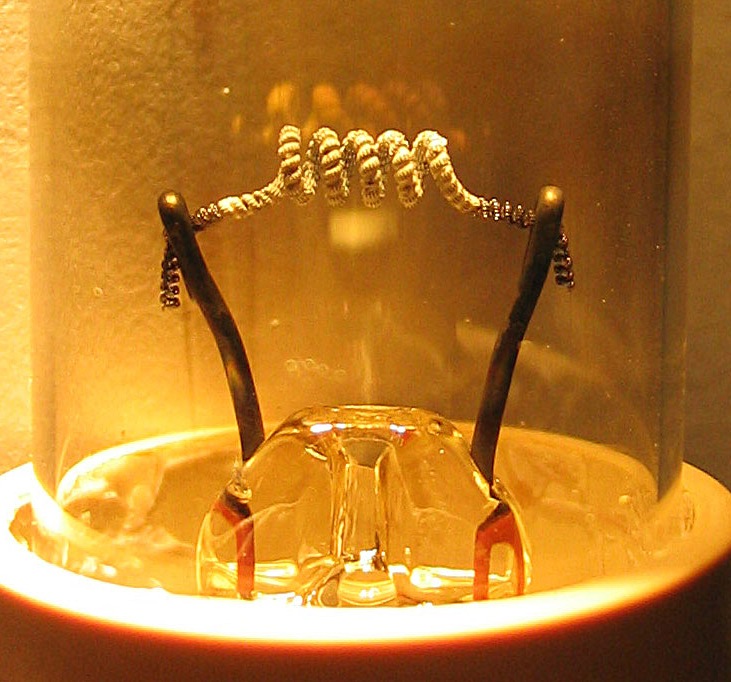

[edit]Thermionic emission was observed again by Thomas Edison in 1880 while his team was trying to discover the reason for breakage of carbonized bamboo filaments[19] and undesired blackening of the interior surface of the bulbs in his incandescent lamps. This blackening was carbon deposited from the filament and was darkest near the positive end of the filament loop, which apparently cast a light shadow on the glass, as if negatively-charged carbon emanated from the negative end and was attracted towards and sometimes absorbed by the positive end of the filament loop. This projected carbon was deemed "electrical carrying" and initially ascribed to an effect in Crookes tubes where negatively-charged cathode rays from ionized gas move from a negative to a positive electrode. To try to redirect the charged carbon particles to a separate electrode instead of the glass, Edison did a series of experiments (a first inconclusive one is in his notebook on 13 February 1880) such as the following successful one:[20]

This effect had many applications. Edison found that the current emitted by the hot filament increased rapidly with voltage, and filed a patent for a voltage-regulating device using the effect on 15 November 1883,[21] notably the first US patent for an electronic device. He found that sufficient current would pass through the device to operate a telegraph sounder, which was exhibited at the International Electrical Exhibition of 1884 in Philadelphia. Visiting British scientist William Preece received several bulbs from Edison to investigate. Preece's 1885 paper on them referred to the one-way current through the partial vacuum as the Edison effect,[22][23] although that term is occasionally used to refer to thermionic emission itself. British physicist John Ambrose Fleming, working for the British Wireless Telegraphy Company, discovered that the Edison effect could be used to detect radio waves. Fleming went on to develop a two-element thermionic vacuum tube diode called the Fleming valve (patented 16 November 1904).[24][25][26] Thermionic diodes can also be configured to convert a heat difference to electric power directly without moving parts as a device called a thermionic converter, a type of heat engine.

Richardson's law

[edit]Following J. J. Thomson's identification of the electron in 1897, the British physicist Owen Willans Richardson began work on the topic that he later called "thermionic emission". He received a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1928 "for his work on the thermionic phenomenon and especially for the discovery of the law named after him".

From band theory, there are one or two electrons per atom in a solid that are free to move from atom to atom. This is sometimes collectively referred to as a "sea of electrons". Their velocities follow a statistical distribution, rather than being uniform, and occasionally an electron will have enough velocity to exit the metal without being pulled back in. The minimum amount of energy needed for an electron to leave a surface is called the work function. The work function is characteristic of the material and for most metals is on the order of several electronvolts (eV). Thermionic currents can be increased by decreasing the work function. This often-desired goal can be achieved by applying various oxide coatings to the wire.

In 1901 Richardson published the results of his experiments: the current from a heated wire seemed to depend exponentially on the temperature of the wire with a mathematical form similar to the modified Arrhenius equation, .[27] Later, he proposed that the emission law should have the mathematical form[28]

where J is the emission current density, T is the temperature of the metal, W is the work function of the metal, k is the Boltzmann constant, and AG is a parameter discussed next.

In the period 1911 to 1930, as physical understanding of the behaviour of electrons in metals increased, various theoretical expressions (based on different physical assumptions) were put forward for AG, by Richardson, Saul Dushman, Ralph H. Fowler, Arnold Sommerfeld and Lothar Wolfgang Nordheim. Over 60 years later, there is still no consensus among interested theoreticians as to the exact expression of AG, but there is agreement that AG must be written in the form:

where λR is a material-specific correction factor that is typically of order 0.5, and A0 is a universal constant given by[29]

where and are the mass and charge of an electron, respectively, and is the Planck constant.

In fact, by about 1930 there was agreement that, due to the wave-like nature of electrons, some proportion rav of the outgoing electrons would be reflected as they reached the emitter surface, so the emission current density would be reduced, and λR would have the value 1 − rav. Thus, one sometimes sees the thermionic emission equation written in the form:

- .

However, a modern theoretical treatment by Modinos assumes that the band-structure of the emitting material must also be taken into account. This would introduce a second correction factor λB into λR, giving . Experimental values for the "generalized" coefficient AG are generally of the order of magnitude of A0, but do differ significantly as between different emitting materials, and can differ as between different crystallographic faces of the same material. At least qualitatively, these experimental differences can be explained as due to differences in the value of λR.

Considerable confusion exists in the literature of this area because: (1) many sources do not distinguish between AG and A0, but just use the symbol A (and sometimes the name "Richardson constant") indiscriminately; (2) equations with and without the correction factor here denoted by λR are both given the same name; and (3) a variety of names exist for these equations, including "Richardson equation", "Dushman's equation", "Richardson–Dushman equation" and "Richardson–Laue–Dushman equation". In the literature, the elementary equation is sometimes given in circumstances where the generalized equation would be more appropriate, and this in itself can cause confusion. To avoid misunderstandings, the meaning of any "A-like" symbol should always be explicitly defined in terms of the more fundamental quantities involved.

Because of the exponential function, the current increases rapidly with temperature when kT is less than W.[further explanation needed] (For essentially every material, melting occurs well before kT = W.)

The thermionic emission law has been recently revised for 2D materials in various models.[30][31][32]

Schottky emission

[edit]

In electron emission devices, especially electron guns, the thermionic electron emitter will be biased negative relative to its surroundings. This creates an electric field of magnitude E at the emitter surface. Without the field, the surface barrier seen by an escaping Fermi-level electron has height W equal to the local work-function. The electric field lowers the surface barrier by an amount ΔW, and increases the emission current. This is known as the Schottky effect (named for Walter H. Schottky) or field enhanced thermionic emission. It can be modeled by a simple modification of the Richardson equation, by replacing W by (W − ΔW). This gives the equation[33][34]

where ε0 is the electric constant (also called the vacuum permittivity).

Electron emission that takes place in the field-and-temperature-regime where this modified equation applies is often called Schottky emission. This equation is relatively accurate for electric field strengths lower than about 108 V⋅m−1. For electric field strengths higher than 108 V⋅m−1, so-called Fowler–Nordheim (FN) tunneling begins to contribute significant emission current. In this regime, the combined effects of field-enhanced thermionic and field emission can be modeled by the Murphy-Good equation for thermo-field (T-F) emission.[35] At even higher fields, FN tunneling becomes the dominant electron emission mechanism, and the emitter operates in the so-called "cold field electron emission (CFE)" regime.

Thermionic emission can also be enhanced by interaction with other forms of excitation such as light.[36] For example, excited Cesium (Cs) vapors in thermionic converters form clusters of Cs-Rydberg matter which yield a decrease of collector emitting work function from 1.5 eV to 1.0–0.7 eV. Due to long-lived nature of Rydberg matter this low work function remains low which essentially increases the low-temperature converter's efficiency.[37]

Photon-enhanced thermionic emission

[edit]Photon-enhanced thermionic emission (PETE) is a process developed by scientists at Stanford University that harnesses both the light and heat of the sun to generate electricity and increases the efficiency of solar power production by more than twice the current levels. The device developed for the process reaches peak efficiency above 200 °C, while most silicon solar cells become inert after reaching 100 °C. Such devices work best in parabolic dish collectors, which reach temperatures up to 800 °C. Although the team used a gallium nitride semiconductor in its proof-of-concept device, it claims that the use of gallium arsenide can increase the device's efficiency to 55–60 percent, nearly triple that of existing systems,[38][39] and 12–17 percent more than existing 43 percent multi-junction solar cells.[40][41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Becquerel, Edmond (1853). "Reserches sur la conductibilité électrique des gaz à des températures élevées" [Researches on the electrical conductivity of gases at high temperatures]. Comptes Rendus (in French). 37: 20–24.

- Extract translated into English: Becquerel, E. (1853). "Researches on the electrical conductivity of gases at high temperatures". Philosophical Magazine. 4th series. 6: 456–457.

- ^ Paxton, William Francis (18 April 2013). Thermionic Electron Emission Properties of Nitrogen-Incorporated Polycrystalline Diamond Films (PDF) (PhD dissertation). Vanderbilt University. hdl:1803/11438. Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ "Thermionic power converter". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- ^ Guthrie, Frederick (October 1873). "On a relation between heat and static electricity". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 4th. 46 (306): 257–266. doi:10.1080/14786447308640935. Archived from the original on 2018-01-13.

- ^ Guthrie, Frederick (February 13, 1873). "On a new relation between heat and electricity". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 21 (139–147): 168–169. doi:10.1098/rspl.1872.0037. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ Richardson, O. W. (2003). Thermionic Emission from Hot Bodies. Wexford College Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-929148-10-3. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31.

- ^ Hittorf, W. (1869). "Ueber die Electricitätsleitung der Gase" [On electrical conduction of gases]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 2nd series (in German). 136 (1): 1–31. Bibcode:1869AnP...212....1H. doi:10.1002/andp.18692120102.

- ^ Hittorf, W. (1869). "Ueber die Electricitätsleitung der Gase" [On electrical conduction of gases]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 2nd series (in German). 136 (2): 197–234. Bibcode:1869AnP...212..197H. doi:10.1002/andp.18692120203.

- ^ Hittorf, W. (1874). "Ueber die Electricitätsleitung der Gase" [On electrical conduction of gases]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie (in German). Jubalband (anniversary volume): 430–445. Archived from the original on 2018-01-13.

- ^ Hittorf, W. (1879). "Ueber die Electricitätsleitung der Gase" [On electrical conduction of gases]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 3rd series (in German). 7 (8): 553–631. Bibcode:1879AnP...243..553H. doi:10.1002/andp.18792430804.

- ^ Hittorf, W. (1883). "Ueber die Electricitätsleitung der Gase" [On electrical conduction of gases]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 3rd series (in German). 20 (12): 705–755. doi:10.1002/andp.18832561214.

- ^ Hittorf, W. (1884). "Ueber die Electricitätsleitung der Gase" [On electrical conduction of gases]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 3rd series (in German). 21 (1): 90–139. Bibcode:1884AnP...257...90H. doi:10.1002/andp.18842570105.

- ^ E. Goldstein (1885) "Ueber electrische Leitung in Vacuum" Archived 2018-01-13 at the Wayback Machine (On electric conduction in vacuum) Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 3rd series, 24: 79–92.

- ^ Elster and Geitel (1882) "Ueber die Electricität der Flamme" (On the electricity of flames), Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 3rd series, 16: 193–222.

- ^ Elster and Geitel (1883) "Ueber Electricitätserregung beim Contact von Gasen und glühenden Körpern" (On the generation of electricity by the contact of gases and incandescent bodies), Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 3rd series, 19: 588–624.

- ^ Elster and Geitel (1885) "Ueber die unipolare Leitung erhitzter Gase" (On the unipolar conductivity of heated gases") Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 3rd series, 26: 1–9.

- ^ Elster and Geitel (1887) "Ueber die Electrisirung der Gase durch glühende Körper" (On the electrification of gases by incandescent bodies") Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 3rd series, 31: 109–127.

- ^ Elster and Geitel (1889) "Ueber die Electricitätserregung beim Contact verdünnter Gase mit galvanisch glühenden Drähten" (On the generation of electricity by contact of rarefied gas with electrically heated wires) Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 3rd series, 37: 315–329.

- ^ "How Japanese Bamboo Helped Edison Make The Light Bulb". www.amusingplanet.com. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ Johnson, J. B. (1960-12-01). "Contribution of Thomas A. Edison to Thermionics". American Journal of Physics. 28 (9): 763–773. Bibcode:1960AmJPh..28..763J. doi:10.1119/1.1935997. ISSN 0002-9505.

- ^ US 307031, Edison, Thomas A., "Electrical indicator", published 1884-10-21

- ^ Preece, William Henry (1885). "On a peculiar behaviour of glow lamps when raised to high incandescence". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 38 (235–238): 219–230. doi:10.1098/rspl.1884.0093. Archived from the original on 2014-06-26. Preece coins the term the "Edison effect" on page 229.

- ^ Josephson, M. (1959). Edison. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-033046-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Provisional specification for a thermionic valve was lodged on November 16, 1904. In this document, Fleming coined the British term "valve" for what in North America is called a "vacuum tube": "The means I employ for this purpose consists in the insertion in the circuit of the alternating current of an appliance which permits only the passage of electric current in one direction and constitutes therefore an electrical valve."

- ^ GB 190424850, Fleming, John Ambrose, "Improvements in instruments for detecting and measuring alternating electric currents", published 1905-09-21

- ^ US 803684, Fleming, John Ambrose, "Instrument for converting alternating electric currents into continuous currents", published 1905-11-07

- ^ O. W. Richardson (1901). "On the negative radiation from hot platinum". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 11: 286–295.

- ^ While the empirical data favoured both the and forms, Richardson preferred the latter, stating that it was theoretically better founded.Owen Willans Richardson (1921). The emission of electricity from hot bodies, 2nd edition. pp. 63–64.

- ^ Crowell, C. R. (1965). "The Richardson constant for thermionic emission in Schottky barrier diodes". Solid-State Electronics. 8 (4): 395–399. Bibcode:1965SSEle...8..395C. doi:10.1016/0038-1101(65)90116-4.

- ^ S. J. Liang and L. K. Ang (January 2015). "Electron Thermionic Emission from Graphene and a Thermionic Energy Converter". Physical Review Applied. 3 (1) 014002. arXiv:1501.05056. Bibcode:2015PhRvP...3a4002L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.3.014002. S2CID 55920889.

- ^ Y. S. Ang, H. Y. Yang and L. K. Ang (August 2018). "Universal scaling in nanoscale lateral Schottky heterostructures". Physical Review Letters. 121 (5) 056802. arXiv:1803.01771. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.056802. PMID 30118283. S2CID 206314695.

- ^ Y. S. Ang, Xueyi Chen, Chuan Tan and L. K. Ang (July 2019). "Generalized high-energy thermionic electron injection at graphene interface". Physical Review Applied. 12 (1) 014057. arXiv:1907.07393. Bibcode:2019PhRvP..12a4057A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.12.014057. S2CID 197430947.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kiziroglou, M. E.; Li, X.; Zhukov, A. A.; De Groot, P. A. J.; De Groot, C. H. (2008). "Thermionic field emission at electrodeposited Ni-Si Schottky barriers" (PDF). Solid-State Electronics. 52 (7): 1032–1038. Bibcode:2008SSEle..52.1032K. doi:10.1016/j.sse.2008.03.002.

- ^ Orloff, J. (2008). "Schottky emission". Handbook of Charged Particle Optics (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-4200-4554-3. Archived from the original on 2017-01-17.

- ^ Murphy, E. L.; Good, G. H. (1956). "Thermionic Emission, Field Emission, and the Transition Region". Physical Review. 102 (6): 1464–1473. Bibcode:1956PhRv..102.1464M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.102.1464.

- ^ Mal'Shukov, A. G.; Chao, K. A. (2001). "Opto-Thermionic Refrigeration in Semiconductor Heterostructures". Physical Review Letters. 86 (24): 5570–5573. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.5570M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.5570. PMID 11415303.

- ^ Svensson, R.; Holmlid, L. (1992). "Very low work function surfaces from condensed excited states: Rydber matter of cesium". Surface Science. 269/270: 695–699. Bibcode:1992SurSc.269..695S. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(92)91335-9.

- ^ Bergeron, L. (2 August 2010). "New solar energy conversion process discovered by Stanford engineers could revamp solar power production". Stanford Report. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ^ Schwede, J. W.; et al. (2010). "Photon-enhanced thermionic emission for solar concentrator systems". Nature Materials. 9 (9): 762–767. Bibcode:2010NatMa...9..762S. doi:10.1038/nmat2814. PMID 20676086.

- ^ Green, M. A.; Emery, K.; Hishikawa, Y.; Warta, W. (2011). "Solar cell efficiency tables (version 37)". Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications. 19 (1): 84. doi:10.1002/pip.1088. S2CID 97915368.

- ^ Ang, Yee Sin; Ang, L. K. (2016). "Current-Temperature Scaling for a Schottky Interface with Nonparabolic Energy Dispersion". Physical Review Applied. 6 (3) 034013. arXiv:1609.00460. Bibcode:2016PhRvP...6c4013A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.6.034013. S2CID 119221695.

External links

[edit]- How vacuum tubes really work with a section on thermionic emission, with equations, john-a-harper.com.

- Thermionic Phenomena and the Laws which Govern Them, Owen Richardson's Nobel lecture on thermionics. nobelprize.org. December 12, 1929. (PDF)

- Derivations of thermionic emission equations from an undergraduate lab Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine, csbsju.edu.

Thermionic emission

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Mechanism

Thermionic emission is the thermally driven release of electrons from the surface of a material, typically a metal or semiconductor, into a surrounding vacuum or low-pressure environment when the provided thermal energy surpasses the material's work function—the binding energy that holds electrons to the solid. This phenomenon occurs primarily at elevated temperatures, enabling applications such as electron sources in vacuum tubes and energy conversion devices.[4][3] The underlying mechanism stems from the statistical distribution of electron energies within the material, governed by Fermi-Dirac statistics, which describe the occupancy of quantum states near the Fermi level. Heating the material increases the average kinetic energy of electrons, effectively widening the energy distribution and populating the high-energy tail with more electrons possessing sufficient energy to overcome the work function barrier at the surface. Upon reaching the surface, these electrons face an image charge potential that slightly lowers the effective barrier, but only those with perpendicular kinetic energy components exceeding the work function escape into the vacuum without reflection.[4][5] Key parameters influencing thermionic emission include the work function φ (typically measured in electron volts, eV), which varies by material and surface orientation, and the operating temperature T (in Kelvin), which determines the thermal energy scale k_B T, where k_B is the Boltzmann constant. For instance, tungsten, a widely used cathode material due to its high melting point and stability, exhibits a work function of approximately 4.5 eV for polycrystalline surfaces. The emission current density depends strongly on these factors, showing an exponential increase with rising temperature as more electrons gain the requisite energy to surmount the barrier. This qualitative temperature dependence underpins the process's sensitivity to heating, with practical emission often requiring temperatures above 1000 K.[6][7][8]Comparison to Other Emission Processes

Thermionic emission, which relies on thermal excitation to liberate electrons from a material's surface, differs fundamentally from other electron emission processes in its energy source and operational requirements. Photoelectric emission, also known as photoemission, occurs when photons with energy exceeding the material's work function eject electrons, requiring no heat but a specific threshold frequency of light. Field emission involves quantum tunneling of electrons through the surface barrier under a strong applied electric field, enabling operation at ambient temperatures without thermal input. Secondary emission, in contrast, is induced by the impact of high-energy particles such as electrons or ions on the surface, producing multiple secondary electrons per incident particle. These mechanisms are classified based on the primary excitation source: thermal for thermionic, photonic for photoelectric, electrical for field, and kinetic for secondary.[9][10] A primary distinction lies in the environmental conditions needed for emission. Thermionic emission demands elevated temperatures, typically above 1000 K (often exceeding 1200°C for practical cathodes), to provide electrons with sufficient kinetic energy to surmount the work function barrier of 3–5 eV, but it requires no external light or electric field. Photoelectric emission operates at room temperature and depends solely on incident light wavelength, with quantum efficiency varying by material (e.g., higher for alkali-coated surfaces). Field emission functions at low temperatures but necessitates intense electric fields on the order of 3 × 10^7 V/cm to distort the potential barrier, often using sharp emitters like carbon nanotubes. Secondary emission also occurs at ambient conditions, triggered by primary particle energies typically in the keV range, yielding gains of 1–10 secondary electrons per incident particle. Schottky emission represents a hybrid, combining thermal activation with moderate field enhancement to lower the effective barrier.[9][10][11]| Emission Type | Energy Source | Temperature Requirement | External Input | Typical Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermionic | Heat | >1000 K | None | 0.01–10 A/cm² |

| Photoelectric | Photons | Ambient | Light (> threshold frequency) | 10^{-6}–10^{-3} A/cm² |

| Field | Electric field | Ambient | High field (>10^7 V/cm) | Up to 10^4 A/cm² (pulsed) |

| Secondary | Particle impact | Ambient | Primary beam (keV energies) | Yield: 1–10 electrons per incident |