Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Touch piece

View on Wikipedia

A touch piece is a coin or medal believed to cure disease, bring good luck, influence people's behaviour, carry out a specific practical action, etc.

What most touch pieces have in common is that they have to be touched or in close physical contact for the 'power' concerned to be obtained and/or transferred. Once this is achieved, the power is assumed to be permanently present in the coin, which effectively becomes an amulet.

Cure of diseases by coins

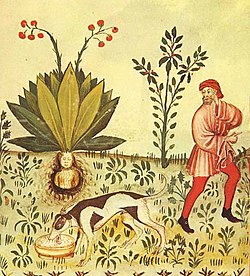

[edit]Coins which had been given at Holy Communion could be rubbed on parts of the body suffering from rheumatism and it was thought that they would effect a cure. Medallions or medalets showing the "Devil defeated" were specially minted in Britain and distributed amongst the poor in the belief that they would reduce disease and sickness.[1] The tradition of touch pieces goes back to the time of Ancient Rome, when the Emperor Vespasian (69–79 AD) gave coins to the sick at a ceremony known as "the touching".[2]

Many touch piece coins were treasured by the recipients and sometimes remained in the possession of families for many generations, as in the case of the "Lee Penny" obtained by Sir Simon Lockhart from the Holy Land whilst on a crusade. This coin, an Edward I groat, still held by the family, has a triangular stone of a dark red colour set into it. The coin is kept in a gold box given by Queen Victoria to General Lockhart.[3] It can supposedly cure rabies, haemorrhage, and various animal ailments. The coin was exempted from the Church of Scotland's prohibition on charms and was lent to the citizens of Newcastle during the reign of King Charles I to protect them from the plague. A sum of between £1,000 and £6,000 was pledged for its return.[4]

The legend of the Lee Penny gave rise to Sir Walter Scott's novel The Talisman. The amulet was placed in water, which was then drunk to provide the cure. No money was ever taken for its use.[5] In 1629 Isobel Young, burned as a witch later that same year,[6] sought to borrow the stone to cure cattle. The family of Lockart of Lee would not lend the stone in its silver setting; however, they gave flagons of water in which the coin had been steeped.[7]

Healing of the King's or Queen's Evil

[edit]

Persons of royal blood were thought to have the "God-given" power of healing this condition by touch, and sovereigns of England and France practised this power to cure sufferers of scrofula, meaning "Swine Evil", as it was common in pigs,[8] a form of tuberculosis of the bones and lymph nodes, commonly known as the "King's or Queen's Evil"[9] or "Morbus Regius". In France it was called the Mal De Roi.[5] William the Lion, King of Scotland is recorded in 1206 as curing a case of scrofula by his touching and blessing a child who had the ailment.[10] Charles I touched around 100 people shortly after his coronation at Holyrood in 1633.[11] Rarely fatal, the disease was naturally given to spontaneously cure itself after lengthy periods of remission. Many miraculous cures were recorded, and failures were put down to a lack of faith in the sufferer. The original Book of Common Prayer of the Anglican Church contained this ceremony. The divine power of kings was believed to be descended from Edward the Confessor, who, according to some legends, received it from Saint Remigius.

The custom lasted from the time of Edward the Confessor until Anne's reign, although her predecessor, William III refused to believe in the tradition and did not practice the ceremony. James II and James Francis Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender, performed the ceremony. Charles Edward Stuart, the "Young Pretender", is known to have carried out the rite in 1745 at Glamis Castle during the time of his rebellion against George II and also in France after his exile. Finally, Henry Benedict Stuart, the brother of Charles, performed the ceremony until his death in 1807. All the Jacobite Stuarts produced special touch-piece medalets, with a variety of designs and inscriptions. They are found in gold, silver and even lead.[12]

Robert II of France was the first to practise the ritual in the 11th century.[5] Henry IV of France is reported as often touching and healing as many as 1,500 individuals at a time. No record survives of the first four Norman kings' attempting to cure by touching; however, there are records of Henry II of England doing so. Mary I of England performed the ceremony[13] and her half-sister, Elizabeth I, cured all "ranks and degrees". William Tooker published a book on the subject, titled Charisma; sive Donum Sanationis.

Queen Anne, amongst many others, touched the 2-year-old infant Samuel Johnson in 1712 to no effect, for although he eventually recovered, he was left badly scarred and blind in one eye.[14] He wore the medal around his neck all of his life and it is now preserved in the British Museum.[15] It was believed that if the touch piece was not worn then the condition would return. Queen Anne last performed the ceremony on 14 April 1714.[16] George I put an end to the practice as being "too Catholic", but the kings of France continued the custom until 1825. William of Malmesbury[17] describes the ceremony in his Chronicle of the Kings of England (1120) and Shakespeare describes the practice in Macbeth.

The gold Angel coins, which were first struck in Britain in 1465 and later dates, particularly of the reigns of James I and Charles I, are often found officially pierced in the centre, as illustrated in Coins of England 2001[18] to be used as touch pieces. The sovereigns of the House of Stuart used the ceremony to help bolster the belief in the "Divine Right of Kings".[19] Charles I indeed issued Angels almost exclusively as touch pieces to the point where intact specimens are hard to come by.[20] He was the first monarch to perform the ceremony in Scotland at Holyrood Palace on 18 June 1633. The size of the hole may indicate the amount of gold taken in payment by the jeweller or the mint for the work of piercing or punching and the provision of a ribbon or silk string.[12]

The cure was usually more of a "laying on of hands" by the monarch and the Angel coin or medalet, etc., although touched by the monarch, was seen as a receipt or talisman of the potential of the monarch's healing power. Originally the king had paid for the support of the sufferer until he had recovered or died. The move to the gift of a gold coin touch piece may represent the compromise payment when the custom of "room and board" support by the king ceased.[5] Coffee in the 18th and early 19th centuries was thought to be a relief, but not a cure for scrofula.

The Angel coin was favoured at these ceremonies because it has on the obverse an image of St. Michael slaying the Devil represented as a dragon (actually a heraldic Wyvern).[21] St. Michael, especially venerated for his role as captain of the heavenly host that drove Satan out of Heaven, was also associated with the casting out of devils and thus was regarded as a guardian of the sick.[22]

The monarch him/herself hung these touch piece amulets around the necks of sufferers. In later years Charles II only touched the medalet as he unsurprisingly disliked touching diseased people directly. He "touched" 92,107 people in the 21 years from 1661 to 1682, performing the function 8,500 times in 1682 alone.[8]

After these coins ceased to be minted in 1634, Charles II had holed gold medalets specially produced by the mint with a similar design of good defeating evil.[9][22] An example of a medalet in the British Museum has a hand descending from a cloud towards four heads, with "He touched them" around the margin, and on the other side a rose and thistle, with "And they were healed."

Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary for 13 April 1661: "To Whitehall to the Banquet House and there saw the King heale, the first time that ever I saw him do it — which he did with great gravity; and it seemed to me to be an ugly office and a simple one."[23] John Evelyn also refers to the ceremony in his Diary on the dates of 6 July 1660 and 28 March 1684.[24]

John Wain in his biography of Dr. Samuel Johnson writes that Johnson was taken by his mother as a small child to London, where after standing in a long line with many others, he was in turn subject to this ritual from Queen Anne.

Unsurprisingly the system was open to abuse and numerous attempts were made to ensure that only the deserving cases got the gold coin, because others would simply sell it.[25]

Luck and coins

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Good luck coins

[edit]

In many countries it was believed that coins with holes in them would bring good luck. This belief could link to a similar superstition linked to stones or pebbles which had holes, often called "Adder Stones" and hung around the neck. Carrying a coin bearing the date of one's birth is purportedly "lucky". In Austria any coin found during a rainstorm is especially lucky, because it is said to have dropped from Heaven. European charms often require silver coins to be used, which are engraved with marks such as an "X" or are bent. These actions personalize the coin, making it uniquely special for the owner. The lucky "sixpence" is a well-known example in Great Britain.

Holy Sacrament communion coins were thought to acquire curative powers over various ailments, especially rheumatism and epilepsy. Such otherwise normal coins, which had been offered at communion, were purchased from the priest for 12 or 13 pennies. The coin was then punched through and worn around the neck of the sick person, or made into a ring.[26]

Gonzalez-Wippler records that if money is left with a mandrake root it will double in quantity overnight. She also stated that the way to ensure the future wealth of a baby is to put part of the child's umbilical cord in a bag together with a few coins. Lucky coins are lucky charms which are carried around attract wealth and good luck, whilst many, often silver coins, attached to bracelets multiply the effect as well as create a noise which scares away evil spirits.[27] Bathing with a penny wrapped in a washcloth brings good fortune at Beltane or the Winter Solstice in Celtic Mythology. Chinese "Money Frogs" or "Money Toads", often with a coin in their mouths, bring food, luck and prosperity.

A Celtic belief is that at the full moon any silver coins on one's person should be jingled or turned over to prevent bad luck, also the silver coins would increase as the moon grew in size.[28] A wish to a new moon could also be made, but not as seen through glass, jingling coins at the same time.[29] American silver "Mercury" dimes, especially with a leap year date, are especially lucky. Gamblers' charms are often these dimes, Mercury being the Roman god who ruled the crossroads, games of chance, etc. Although these dimes actually figure the head of Liberty, people commonly mistake it for Mercury. A silver dime worn at the throat will supposedly turn black if someone tries to poison the wearer's food or drink. American "Indian Head" cents are worn as amulets to ward off evil or negative spirits. In Spain a bride places a silver coin from her father in one shoe and a gold coin from her mother in the other. This will ensure that she will never want for anything. Silver coins were placed in Christmas puddings and birthday cakes to bring good luck and wealth.[28] A variation on this custom was that in some families each member added a coin to the pudding bowl, making a wish as they did so. If their coin turned up in their bowl it's said their wish was sure to come true. In Greece, a coin is added to vasilopita, a bread baked in honor of the feast day of St. Basil the Great. At midnight the sign of the cross is etched with a knife across the cake, to bless the house and bring good luck for the new year. A piece is sliced for each member of the family and any visitors present at the time, and the person who gets the slice with the coin will receive good luck, and often a gift.

In Japan the five-yen coin is considered lucky because "five yen" in Japanese is go en, which is a homophone with go-en (御縁), en being a word for causal connection or relationship, and "go" being a respectful prefix. Therefore, they are often used at shrines as well as the first money put into a new wallet.

In ancient Rome "good luck" coins were in common circulation. "Votive pieces", for example, were struck by new emperors, promising peace for a set number of years. Citizens would hold such coins in their hand when making a wish or petitioning the gods.[26]

Coins bearing religious symbols are often seen as lucky; for instance, the Mogul emperor Akbar's rupees carry words from the Islamic faith, and in India the Ramatanka shows the Hindu god Rama, his wife, Sita, his brother and the monkey god, Hanuman. Gold ducats issued in the name of the mid-18th century Doge Loredano of Venice bore an image of Christ and were issued to be worn as pendants by pilgrims. The Shinto religion has a shrine called Zeniariai-Benten where followers wash their money in the spring water at certain times of year to ensure that it doubles in quantity. In Roman times, sailors placed coins under the masts of their ships to ensure the protection of the gods from the wrath of the sea.[2]

A rare example of a "Wish Tree" exists near Ardmaddy House in Argyll, Scotland. The tree is a hawthorn, a species traditionally linked with fertility, as in "May Blossom." The trunk and branches are covered with hundreds of coins which have been driven through the bark and into the wood. The local tradition is that a wish will be granted for each of the coins so treated.[30] Many pubs, such as the "Punch Bowl" in Askham, near Penrith in Cumbria have old beams with splits in them where coins are forced "for luck."

In some countries, finding a coin on the ground, then keeping it is considered to provide the finder with good luck for the rest of the day, a belief reflected in the adage "Find a penny, pick it up, all day long you'll have good luck'.[31] Variants of this superstition include good luck only being given to the finder if the coin is found face up, or bad luck being given to the finder if the coin is picked up when it was lying face down.

Another local custom at Askham is the throwing of coins from the nearby bridge onto a boulder that lies just below the water level of the river. Getting the coin to land on the rock gives the thrower "good luck." Obvious connections exist with water generally and the practice of throwing in coins to seek favours of the water spirits. The Lady's Well in Kilmaurs, Scotland, is a typical wishing well. At St. Cuby's Well (SX224 564) in Cornwall the legend was that if anyone did not leave an offering of money then they would be followed home by Piskies in the shape of flying moths, embodying the spirits of the dead.[32] At Loch na Gaire in Sutherland, Scotland, it was the tradition to throw coins into the waters to ensure that the waters kept their healing properties.[33]

A "Black Saxpence" in Scots, is a sixpence, supposed by the credulous to be received from the devil, as a pledge of an engagement to be his, soul and body. It is always of a black colour, as not being legal currency; but it is said to possess this singular virtue, that the person who keeps it constantly in his pocket, how much soever he spend, will always find another sixpence beside it.

A Devonian superstition is that carrying crooked coins is good luck and keeps the devil away.[34]

In an example of a modern lucky coin custom, a Canadian sports official secretly embedded a loonie (CAD $1 coin) in the ice of the hockey rink at the 2002 Winter Olympics. Both the Canadian men's and women's hockey teams went on to win gold medals. Canadians have gone on to hide coins in rinks in several subsequent international competitions, and in the foundations of the buildings for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. The Royal Canadian Mint has produced a "lucky loonie" commemorative coin for each Winter Olympics since 2002.

Bad luck coins

[edit]In Ireland it is thought to be bad luck to give money away on a Monday.

The 1932 silver yuan coin from China showed a junk, rays of sunshine and a flock of birds. These were seen as symbolising Japan (the rising sun) and its fighter planes (the birds) invading China. The coin was re-issued in 1933 without the sun or the birds.

The "Godless" florin featured a young Queen Victoria but omitted the customary inscriptions Dei Gratia (by the grace of god) as well as Fidei Defensor (defender of the faith), and was regarded as bringing bad luck.

Finding money was bad luck in some cultures and the curse could only be removed by giving away the money.[2]

It is considered bad luck to have an empty pocket, for even a "crooked coin" keeps the devil away.[35]

Love tokens

[edit]

The bent coin as a love token may be derived from the well-recorded practice of bending a coin when making a vow to a saint, such as vowing to give it to the saint's shrine if the saint would intercede to cure a sick human, animal, etc. Bending a coin when one person made a vow to another was another practice which arose from this.[36]

Protection against evil

[edit]It was believed that the gift of second sight came from the devil; as protection, a silver coin was used to make a cross above the palm of a Gypsy fortune-teller, thus dispelling any evil. In Japan, Korea and Indonesia, coins were made tied together to form sword shapes which were thought to terrify, and therefore ward off, evil spirits. They were also hung above the beds of sick people to drive off the malevolent spirits who were responsible for the illness.[28]

Curse coins

[edit]In 2007 a lead "coin-based" curse on a Roman emperor was found by a metal detector user in Lincolnshire. The 1,650-year-old curse was an act of treason, blasphemy and criminal defacement of the imperial coinage. The perpetrator had cursed the emperor Valens by hammering a coin with his image into lead, then folding the lead over his face. Thousands of ordinary lead cursing charms exist with written inscriptions and a small hole for suspending them.[37]

Touch pieces that influence behaviour

[edit]Coins placed on the eyes of the dead, if briefly dropped into the drink of a husband or wife, would "blind" them to any infidelities that the partner might be involved in.[1]

Also, some groups say that if a penny is thrown into a person's drink, they must "down" the rest of it.[citation needed]

Coins carrying out a specific practical action

[edit]

In Germany, since Medieval times, it was believed that a silver coin with a Sator square engraved on it will put out a fire if thrown into the conflagration.[citation needed] Coins were placed on the eyes of a corpse to prevent them from opening and also in Greek mythology as payment for the ferryman who would carry the dead person across the River Styx into Hades.[28] In the 17th century coins bearing an engraving of St. George were carried by soldiers as a protection against injury following a lucky escape when a bullet hit such a coin and the soldier remained uninjured (Coins of the World).[citation needed] Some of the gold coins of Edward III carry the cryptic legend: IHS MEDIVM ILLORVM IBAT ("But Jesus passing through the midst of them, went his way" – St'Luke IV. 30). According to Sir John Mandeville, this was a spell against the power of thieves.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Waring, Philippa (1987). The Dictionary of Omens & Superstitions. Treasure Press. ISBN 1-85051-009-1

- ^ a b c Coins of the World. De Agostini (2000).

- ^ Leighton, John M. (1840?). Strath-Clutha or the Beauties of the Clyde. Glasgow. p. 24.

- ^ Westwood, Jennifer and Kingshill, Sophia (2009). The Lore of Scotland. A guide to Scottish Legends. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-905211-62-3 p. 192

- ^ a b c d Coin News, April 2005. Token Publishing. ISSN 0958-1391. pp. 29–32.

- ^ "Broadside account concerning trials and executions for 'Witchcraft, Adultery, Fornication, &c. &c.'". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1885). Domestic Annals of Scotland. Edinburgh: W & R Chambers. pp. 233–234.

- ^ a b Coin News, January 1999. Token Publishing. ISSN 0958-1391. pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b Bradley, Howard W. (1978). A Handbook of Coins of the British Isles. Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7091-6747-4. p. 165.

- ^ Dalrymple, Sir David (1776). Annals of Scotland. London: J. Murray. pp. 300–301.

- ^ Daniel, William S. (1852), History of The Abbey and Palace of Holyrood. Edinburgh: Duncan Anderson. p. 117.

- ^ a b Coin News, May 2005. Token Publishing. ISSN 0958-1391. pp. 36–38.

- ^ Ross, Josephine (1979). The Tudors. London: Arctus. p. 118.

- ^ Coin News, December 2003. Token Publishing. ISSN 0958-1391. pp. 50–51.

- ^ "medal | British Museum".

- ^ Werrett, Simon (2000). "Healing the Nation's Wounds: Royal Ritual and Experimental Philosophy in Restoration England". History of Science. 38 (4): 377–399. Bibcode:2000HisSc..38..377W. doi:10.1177/007327530003800402. S2CID 161821600.

- ^ William of Malmesbury, (1815). Chronicle of the Kings of England, J. A. Giles (ed.), trans. John Sharpe. London: George Bell and Sons, 1904.

- ^ Coins of England and the United Kingdom. (2001). 36th Edition. Spink. ISBN 1-902040-36-8.

- ^ McKay, James and Mussell, John W. (eds.) (2001). The Coin Yearbook 2001. Token Publishing. ISBN 1-870192-36-2. p. 112.

- ^ Sutherland, C.H.V. (1982). English Coinage 600–1900. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-0731-X. P. 164.

- ^ Lobel, Richard; Davidson, Mark; Hailstone, Allan and Calligas, Eleni (1999). Coincraft's 1999 Standard catalogue of English and UK Coins 1066 to Date. Coincraft. ISBN 0-9526228-6-6. p. 153.

- ^ a b Seaby, Peter (1985). The Story of British Coinage. Seaby. ISBN 0-900652-74-8 p. 119.

- ^ Latham, Robert (ed.) (1985). The Illustrated Pepys. Extracts from the Diary. Bell & Hyman. ISBN 0-7135-1328-4. p. 30.

- ^ a b Chamberlain, C. C. (1963). The Teach Yourself Guide to Numismatics: An A.B.C. of coins and coin collecting. English Universities Press. pp. 4, 166.

- ^ Roud, Steven (2003). The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland. Penguin Books. p. 395.

- ^ a b Coin News. Pub. Token. ISSN 0958-1391. July 2005. p. 40.

- ^ Gonzalez-Wippler, Migene (2001). The Complete Book of Amulets and Talismans. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 0-87542-287-X.

- ^ a b c d Coin News. Pub. Token. ISSN 0958-1391. July 2002. pp. 43–45.

- ^ Griffith, M.J.S. (1970). Oral communication to Griffith, Roger S. Ll.

- ^ Rodger, Donald, Stokes, John & Ogilve, James (2006). Heritage Trees of Scotland. The Tree Council. p. 87. ISBN 0-904853-03-9.

- ^ "Penny Superstition". Psychic Library. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Straffon, Cherly (1998). Fentynyow Kernow. In Search of Cornwall's Holy Wells. Pub. Meyn Mamvro. p. 25 ISBN 0-9518859-5-2.

- ^ Beare, Beryl (1996), Scotland. Myths & Legends. Pub. Parragon, Avonmouth. p. 66 ISBN 0-7525-1694-9.

- ^ Hewett, Sarah (1900). Nummits and Crummits. Devonshire Customs, Characteristics and Folk-lore. Pub. Thomas Burleigh. p. 51.

- ^ Hewett, Sarah (1900). Nummits and Crummits. Devonshire Customs, Characteristics and Folk-lore. Pub. Thomas Burleigh. p. 52.

- ^ Coin News. Pub. Token. ISSN 0958-1391. July 1998. p. 29.

- ^ "Roman Curse Coin". Retrieved 2009-11-12.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 6.

- [1] Laying on of Hands

- The 'Lee Penny' at Electric Scotland

- Dr Johnson's Touch piece

- [2] The Lucky Coin

Touch piece

View on GrokipediaHistorical Origins

Ancient Precedents

In ancient Lydia, circa 600 BC, the world's earliest coinage emerged under kings like Alyattes, consisting of electrum staters stamped with a lion's head motif symbolizing royal strength and authority. These coins, weighing approximately 4.7 grams and featuring punch marks for authentication, facilitated standardized trade while embodying the sovereign's power, often interpreted as divinely sanctioned due to the region's wealth and the kings' legendary prosperity under Croesus.[8][9] Although lacking explicit ritual use for healing, Lydian coinage established coins as tangible extensions of monarchical legitimacy, a foundation for later associations between numismatic objects and supernatural or authoritative efficacy. Roman practices advanced this symbolic role, with coins frequently employed as votive offerings in rituals seeking divine intervention for health and prosperity. Deposited in temples, sacred springs, and during ceremonies, they invoked deities like Asclepius or Salus, especially amid epidemics, as evidenced by issues struck with healing iconography such as the goddess Salus extending her hand or serpents symbolizing renewal.[10] Emperors propagated such beliefs through coinage promising pax (peace) and salus (health), like Vespasian's aurei depicting Pax with an olive branch or caduceus, distributed empire-wide to affirm restorative imperial benevolence.[11] A direct precursor to formalized touch rituals appears under Emperor Vespasian (r. 69–79 AD), who conducted public healings in Alexandria, restoring sight to the blind by spittle and mobility to the lame by foot-touch, as corroborated by Tacitus, Suetonius, and Dio Cassius. During these ceremonies, Vespasian distributed coins to the afflicted, linking the emperor's purported thaumaturgic power—framed within Egyptian and imperial cult traditions—to the tokens themselves, prefiguring the transfer of curative virtue via royal contact.[12][13][14] This practice, distinct from mere almsgiving, underscored coins as conduits for the ruler's salubrious aura, though primary accounts emphasize the touch over the numismatic element.Development in Medieval Europe

The royal touch for scrofula, a tuberculous condition of the lymph nodes known as the "King's Evil," was first attributed to Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066) in England, where hagiographic accounts described him healing afflicted subjects through physical contact followed by provision of alms for their upkeep until recovery, framing the monarch as a divinely sanctioned healer akin to biblical kings.[15][2] This rite integrated Christian sacramental theology with monarchical authority, positing the king's anointing at coronation as conferring miraculous powers derived from God, thereby reinforcing political legitimacy amid feudal fragmentation.[16] Early iterations involved distributing ordinary coins or silver as charitable tokens post-touch, serving both practical support and symbolic reinforcement of the king's role as a conduit for divine grace, with recipients often wearing them as protective talismans against relapse.[17] By the late fifteenth century, under Henry VII (r. 1485–1509), the practice shifted toward dedicated gold angels—noble coins valued at 6s 8d, featuring the Archangel Michael spearing a dragon on the obverse to evoke triumph over sin and disease—pierced for suspension and explicitly touched during ceremonies to imbue them with curative potency.[1][18] These specialized pieces symbolized doctrinal purity and royal piety, evolving coinage from mere currency into ritual artifacts that extended the touch's efficacy beyond the immediate rite. Parallel developments occurred on the Continent, particularly in France, where Capetian kings from Philip I (r. 1060–1108) onward claimed similar thaumaturgic abilities for scrofula by the eleventh century, often distributing medals or coins in healing rituals tied to sacred monarchy, though English numismatic survivals provide more direct evidence of medieval integration.[19][20] This convergence underscored a broader medieval synthesis of relic veneration and regnal power, where touched objects blurred lines between ecclesiastical miracles and secular governance.The Royal Touch Tradition

Ceremony for Healing Scrofula

The ceremony for healing scrofula, a form of tuberculous lymphadenitis known historically as the King's Evil, centered on the monarch's ritual laying of hands on the swollen cervical lymph nodes of patients, predicated on the divine right of kings to channel God's curative power.[15][2] Public sessions were scheduled around major Christian holy days, including Easter, Whitsun, Michaelmas, and Christmas, allowing hundreds or thousands of subjects to approach the sovereign in formal gatherings often held in royal chapels or palaces.[21] Prior to participation, prospective patients underwent vetting by royal surgeons, who diagnosed scrofula and consulted records to exclude prior attendees, preventing fraudulent claims; admission was facilitated by official tickets issued to verified sufferers.[22][23] In the ritual itself, following prayers or a service, the monarch touched the afflicted areas directly, invoking the healing authority derived from biblical precedents of laying on hands for recovery.[16] Afterward, each patient received an angel coin pressed into their hand or hung around the neck as a talisman to sustain the touch's purported virtue against relapse.[15] Under Charles II, these events scaled dramatically post-Restoration, with the king touching thousands annually—such as 6,725 individuals in 1660 and around 4,000 per year thereafter—eyewitnessed by contemporaries like Samuel Pepys, who recorded observing the procedure amid crowds at Whitehall.[24][25][26] Over his reign, Charles II reportedly laid hands on approximately 100,000 scrofula patients, underscoring the ceremony's logistical demands and public faith in monarchical thaumaturgy despite emerging medical skepticism.[22][21]Evolution Across English Monarchs

The tradition of the royal touch, accompanied by the distribution of specially prepared gold coins such as angels, persisted without significant alteration from the reign of Elizabeth I into that of James I (1603–1625), reflecting continuity in the assertion of monarchical divine authority amid religious and political transitions.[1] James I upheld the practice, issuing gold touch pieces that have surfaced in contemporary archaeological contexts, including a rare example unearthed in Cornwall in June 2025, highlighting the enduring material legacy of Jacobean-era ceremonies.[27] Under Charles I (1625–1649), economic pressures from the English Civil War prompted adaptations, with gold shortages leading to the substitution of silver coins as touch pieces to sustain the healing rituals despite wartime constraints on royal resources.[1] The Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 under Charles II (1660–1685) marked a resurgence, as the king leveraged the touch to reinforce legitimacy, conducting ceremonies that drew thousands annually—peaking at nearly 100,000 touches over his reign—and commissioning the Royal Mint to produce dedicated gold medals from 1664/5 onward, enabling broader distribution than prior bespoke adaptations.[2][23] The practice waned in the early 18th century, with Queen Anne (1702–1714) as the final English monarch to perform it; she reintroduced formalized touchings with issued gold pieces but conducted the last recorded ceremony on 27 April 1714, shortly before her death, as Enlightenment-era rationalism eroded belief in royal healing powers and diminished the political utility of such rites.[2][15]Varieties and Attributed Powers

Medicinal and Curative Applications

Touch pieces were predominantly employed in rituals aimed at curing scrofula, a form of tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis manifesting as swollen lymph nodes in the neck, through the monarch's touch combined with the distribution of specially prepared coins as amulets.[2] In these ceremonies, English sovereigns from Edward the Confessor onward laid hands on sufferers, often making the sign of the cross over the affected areas, before presenting pierced gold angels—depicting the Archangel Michael slaying a dragon—as talismans to be worn on a ribbon around the neck for ongoing protective and curative efficacy.[28] These coins, such as those issued under Henry VIII between 1543 and 1547, were believed to retain the healing virtue imparted by the royal contact, with patients instructed to keep them close to the skin.[29] Historical records document numerous anecdotal testimonies of successful healings attributed to this practice, including claims of rapid resolution of scrofulous swellings following the touch and amulet use, as recounted in contemporary accounts of royal ceremonies where thousands sought relief annually.[16] For instance, during the reigns of Tudor and Stuart monarchs, diarists and court observers noted instances where patients reportedly experienced marked improvement or full recovery, fueling the persistence of the tradition despite the absence of controlled verification.[1] However, archival evidence from healing sessions, such as those under Charles II, implies frequent non-resolutions, with many recipients returning untreated or the condition progressing, as routine cures were not universally proclaimed and demand persisted unabated.[5] Beyond scrofula, folk applications of touch pieces extended to other maladies like epilepsy, where worn coins were credited with averting seizures in popular belief, though such uses lacked the formalized royal endorsement and evidentiary basis confined to the king's evil.[28] These extensions reflect broader amuletic traditions but remained ancillary to the primary curative claim against tubercular lymphadenopathy, with no systematic royal rituals documented for alternative diseases.[2]Protective and Apotropaic Uses

Touch pieces, consecrated through the monarch's ritual touch, extended beyond curative functions to serve as apotropaic devices against supernatural perils, including evil spirits and witchcraft. Worn as pendants—often pierced for ribbon suspension—these coins were believed to harness the sovereign's divinely sanctioned power to repel malevolent influences, preventing affliction rather than remedying it. Historical records from the 17th century onward document recipients, such as writer Samuel Johnson, who retained and wore touch pieces lifelong for sustained safeguarding.[30][31] This protective role drew from broader traditions of coinage as wards, where precious metals like gold and silver, coupled with Christian motifs such as the Archangel Michael slaying a dragon on Angel touch pieces, were thought inherently antagonistic to demonic forces. In medieval England, silver coins were specifically invoked to counter witchcraft, with their purity symbolizing resistance to corruption by evil. Touch pieces amplified this through royal consecration, distinguishing them as potent talismans; for instance, during the Restoration, Charles II's issues were carried or buried in homes to shield against misfortune attributed to supernatural agency.[32][33] Archaeological evidence supports such uses, with intentionally holed or modified coins found in medieval deposits, interpreted as enhancements for apotropaic efficacy by enabling wear or ritual placement. While not exclusively touch pieces, this practice paralleled their adaptation, where piercing not only facilitated adornment but ritually "activated" the coin's defensive properties against curses or spectral harms. Beliefs in "reversing" curse-bearing coins—through bending or marking to neutralize spells—occasionally incorporated monarch-touched examples, leveraging the touch's presumed exorcistic potency to invert malevolent intent.[34][33]Tokens for Luck, Love, and Influence

Touch pieces extended beyond curative uses in folklore to attributions of conferring good or bad luck, with specific examples tied to monarchs like Charles II (reigned 1660–1685), whose angel coins were regarded as particularly auspicious for fortune due to their association with restoration-era prosperity and royal favor.[35] These coins, often retained as heirlooms, were believed to attract health, wealth, and general good fortune when carried or worn, reflecting broader superstitious views of royal-imparted objects as talismans against misfortune.[36] Certain dates or types, such as those minted during periods of perceived royal strength, amplified this reputation, though empirical evidence for such effects remains absent, attributable instead to confirmation bias in anecdotal reports.[35] In relational contexts, touch pieces were adapted as love tokens through engraving or gifting, leveraging their perceived inherent power to symbolize enduring affection and fidelity. Historical records from the 18th and 19th centuries document silver or gold touch pieces modified with initials, hearts, or vows, worn as pendants or exchanged in courtship, where the royal touch purportedly enhanced the token's efficacy in binding emotions or ensuring loyalty. This practice merged numismatic value with sentimental engraving traditions, prevalent among the poor and middling sorts, though primarily driven by cultural custom rather than verified causal influence on relationships.[37] Rarer attributions involved "influence" pieces intended to sway behavior, such as promoting obedience or persuasion, rooted in folklore claims of the coins' residual royal authority extending to interpersonal dynamics.[38] Period texts describe these as charms gifted to induce compliance or favor, but such uses lack substantiation beyond testimonial accounts, likely reflecting placebo-like expectations rather than objective effects. Misuse for harm, including curse coins aimed at ill will, appears minimally documented, with ethical concerns in contemporary writings distinguishing defensive from malevolent applications, though primary evidence prioritizes benign superstitious intents over deliberate malice.Notable Examples and Artifacts

The Angel Coin and Derivatives

The Angel coin, a gold piece valued at 6s 8d, was introduced by Edward IV in 1465 as a derivative of the earlier noble, drawing inspiration from the French angelot.[36] Its obverse depicted the Archangel Michael spearing a dragon, symbolizing the triumph of good over evil, which aligned with the royal touch's purported power to conquer scrofula, interpreted as the "king's evil" akin to demonic affliction.[5] This imagery evoked St. Michael's role as a healer and protector against disease in medieval lore, reinforcing the coin's talismanic role when presented during healing ceremonies.[5] Angels were routinely pierced for suspension as pendants, allowing recipients to wear them as ongoing amulets post-touching, which contributed to their elevated survival rate compared to circulating currency due to preserved talismanic significance.[1] Numismatic records document this adaptation, with examples from Edward IV onward showing consistent perforations for ribbon attachment during rituals.[5] Derivatives persisted under subsequent monarchs, such as Mary I (1553–1558), whose Angels retained the St. Michael motif and were pierced for use in touching ceremonies, as evidenced by surviving specimens in catalogs of the British Numismatic Society.[5] These variants maintained the archetypal design's lineage, evolving minimally while serving the same symbolic function in royal numismatics until the tradition's decline.[36]Special Issues from the Restoration Period

Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Charles II reinstated the royal touch for scrofula, prompting the minting of purpose-made gold touchpieces from 1664/65 at the Tower of London Mint under engraver John Roettiers. These 22-carat milled pieces initially weighed 54.3 grains (yielding 106 per troy pound), reducing to 30 grains in August 1684 amid fiscal considerations; the obverse bore a sailing ship with the legend "CAROLVS II D G MAG BRI FR ET HIB REX," while the reverse depicted St. Michael vanquishing the dragon inscribed "SOLI DEO GLORIA." The inaugural striking produced approximately 6,700 pieces, with overall output totaling around 105,000 to supply the over 100,000 subjects touched across his 25-year reign, often at multiple annual sessions like Easter and Whitsun.[5][39] James II continued the tradition upon his 1685 accession, issuing comparable 22-carat gold touchpieces of 30 grains, updating the obverse to "IACOBVS II D G MAG BRI FR ET HIB REX" but reusing Charles II's reverse design and dies; initial distributions drew from Charles's surplus stock. Production averaged about 12,000 pieces annually, including 14,364 in the first documented year (1686/87), reflecting intensified ceremonies without fixed session limits and touching thousands before his 1688 deposition ended Restoration-era mintings. These bespoke emissions, struck en masse yet lost to attrition through piercing, wear, and dispersal, survive in scant numbers today; intact specimens command premium auction prices, such as thousands of pounds for verified examples, underscoring their dual numismatic and thaumaturgic provenance.[5][41]

Empirical Evaluation and Skepticism

Medical Understanding of Scrofula

Scrofula, also known as tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis, is a form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis characterized by infection of the cervical lymph nodes primarily caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with Mycobacterium bovis as a less common etiology in regions where unpasteurized dairy is consumed.[42][43] The pathology involves hematogenous or lymphatic spread from a primary pulmonary focus, leading to granulomatous inflammation, caseation necrosis, and enlargement of neck lymph nodes, which may progress to abscess formation, suppuration, and sinus tract development if untreated.[44][45] In the pre-antibiotic era, the condition often manifested as chronic, indolent swelling observable as painless or tender masses in the neck, with potential for spontaneous resolution in some cases due to the host's immune containment of the infection, though progression to disseminated disease or secondary bacterial superinfection could result in significant morbidity or mortality.[46][22] Prior to the establishment of germ theory in the late 19th century, diagnosis relied solely on clinical observation of persistent lymphadenopathy, without microbiological confirmation or understanding of the infectious etiology; swellings were noted for their resemblance to a brood sow's ("scrofula" deriving from Latin scrofa), and differentiation from other inflammatory or neoplastic processes was rudimentary, often based on chronicity and lack of acute suppuration.[43] Louis Pasteur's experiments in the 1860s laid foundational work for germ theory by demonstrating microbial causation in fermentation and disease, but the specific identification of M. tuberculosis as the pathogen awaited Robert Koch's 1882 isolation and staining of the bacillus from tuberculous lesions.[47][48] This bacteriological breakthrough shifted comprehension from humoral imbalances or constitutional weaknesses—prevalent in medieval and early modern medical thought—to a causal infectious model, explaining why historical attributions of cure to non-causal interventions like royal touch coincided with the disease's variable natural history rather than any therapeutic effect.[22] Contemporary management contrasts sharply with historical outcomes, employing multi-drug antitubercular regimens such as isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 6-9 months, achieving cure rates exceeding 90% in drug-susceptible cases, alongside surgical excision for persistent nodes or complications.[49] Empirical studies confirm that spontaneous remissions, observed in up to 20-30% of untreated pediatric cases due to immune-mediated quiescence, could mimic recovery and fuel non-etiological explanations, but no evidence links physical contact or ritual to altered disease progression beyond placebo or coincidence.[22][46] In resource-limited settings today, scrofula remains a marker of underlying TB endemicity, with diagnosis now integrating fine-needle aspiration cytology, acid-fast bacilli smears, culture, and nucleic acid amplification tests for confirmatory precision.[50]Rational Critiques and Alternative Explanations

The absence of randomized controlled trials or systematic comparative studies in the pre-modern era renders claims of efficacy for touch pieces unverifiable, with anecdotal successes more plausibly explained by the placebo response—wherein belief in the treatment induces subjective symptom relief—or statistical phenomena such as regression to the mean and spontaneous remission, common in fluctuating conditions like scrofula.[22] Reported cure rates did not demonstrably exceed baseline recovery expectations from natural disease progression, as contemporary surgical observations indicated variable outcomes independent of ritual intervention.[51] English surgeon William Beckett, in his 1722 treatise A Free and Impartial Enquiry into the Antiquity and Efficacy of Touching for the Cure of the King's Evil, dissected historical precedents and medical records, concluding that the royal touch conferred no advantages over conventional remedies or inaction, attributing purported miracles to confirmation bias and selective reporting of favorable cases.[52] Beckett's analysis highlighted inconsistencies in cure attributions, noting that similar healing anecdotes appeared in non-royal contexts, undermining the uniqueness of monarchical or coin-mediated intervention.[53] Enlightenment-era rationalism further delegitimized the practice, fostering widespread doubt as empirical methods supplanted faith-based assertions; by the early 18th century, figures like physician Richard Blackmore echoed Beckett in dismissing the touch as superstitious, contributing to its abandonment under the Hanoverians starting with George I's 1714 accession.[54][51] This shift reflected broader causal scrutiny, where monarchical legitimacy increasingly derived from constitutional and institutional sources rather than purported thaumaturgic powers.[22] Sociologically, touch pieces functioned as psychological palliatives in a medically primitive context, alleviating despair through ritual participation and communal validation while bolstering absolutist ideology by linking the sovereign's persona to divine favor, independent of therapeutic outcomes.[54] Such mechanisms persisted amid evidentiary voids, prioritizing symbolic cohesion over falsifiable claims, until scientific paradigms rendered them obsolete.[51]Collectibility and Contemporary Relevance

Numismatic Significance

Touch pieces represent a niche but valued segment of British numismatics, prized for their limited production runs, distinct modifications such as piercing for suspension, and association with specific royal issuers from the 16th to 18th centuries. Their scarcity—stemming from ceremonial distribution rather than mass minting—elevates them beyond standard coinage, with collectors seeking examples that demonstrate authentic period use through edge wear and suspension holes. Scholarly classification, as detailed in the British Numismatic Journal, identifies approximately a dozen primary types excluding die variants, encompassing gold Angels under Henry VII through silver pieces under Queen Anne, providing a structured framework for attribution and study.[17] Market value derives substantially from provenance and condition, with premiums accruing to pieces verifiably linked to early issuers like James I, where handling wear paradoxically serves as evidence of historical authenticity despite reducing modern grading scores. A pierced gold Angel of James I (second coinage), marked with a mullet and exhibiting characteristic use-wear, realized £8,500 at auction, reflecting demand for such rarities among institutional and private collectors. Later examples, such as James II gold touch pieces, have fetched £2,500 or more in comparable sales, underscoring a tiered valuation favoring pre-Restoration issues.[55][56] The gold content in earlier types, like Angels valued at around 10 shillings nominally but far exceeding melt value today, coupled with intense collector interest, exposes touch pieces to forgery risks, including altered contemporary coins or fabricated replicas mimicking suspension features and patina. Authentication thus relies on metallurgical analysis, die studies, and provenance documentation from reputable auction houses to mitigate these vulnerabilities, as generic visual inspections often fail against sophisticated counterfeits targeting high-value numismatic items.[55][57]Recent Archaeological Finds

In June 2025, metal detectorists unearthed a rare gold touch piece from the reign of King James II (r. 1685–1688) in Cornwall, accompanied by a post-medieval engraved posy ring inscribed with romantic verse.[27][58] The touch piece, featuring the traditional depiction of St. Michael vanquishing the dragon, was confirmed as over 300 years old through expert assessment, highlighting the persistence of royal healing rituals into the late Stuart period.[27] Such discoveries are typically recorded via the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which documents public finds to aid archaeological research and prevent illicit trade.[59] Metal detectorists have also recovered silver coins adapted for use as touch pieces, including a pierced 1679 Charles II threepence modified to align the central figure of St. Michael when viewed through the hole, indicative of its role as a wearable talisman post-touching ceremony.[1] Examination of these artifacts often reveals smoothed edges or suspension holes from prolonged handling and wear, consistent with folk medicinal practices rather than mere currency circulation.[1] These post-2000 recoveries, primarily from rural fields via responsible detecting, demonstrate touch pieces' widespread dispersal beyond urban or courtly settings, implying monarchs distributed them to common supplicants during peripatetic healing sessions and challenging prior assumptions of primarily elite or institutional retention.[60][59] The geographic scatter in England suggests patterns tied to royal progresses, with implications for mapping 17th-century belief in the king's touch across socioeconomic strata.[1]References

- https://www.britnumsoc.[org](/page/.org)/publications/Digital%20BNJ/pdfs/1979_BNJ_49_11.pdf