Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cimaruta

View on Wikipedia

The cimaruta ("chee-mah-roo-tah"; plural cimarute) is an Italian folk amulet or talisman, traditionally worn around the neck or hung above an infant's bed to ward off the evil eye (Italian: mal'occhio). Commonly made of silver, the amulet itself consists of several small apotropaic charms (some of which draw upon Christian symbolism), with each individual piece attached to what is supposed to represent a branch of rue—the flowering medicinal herb for which the whole talisman is named, "cimaruta" being a Neapolitan form of cima di ruta: Italian for "sprig of rue".[1]

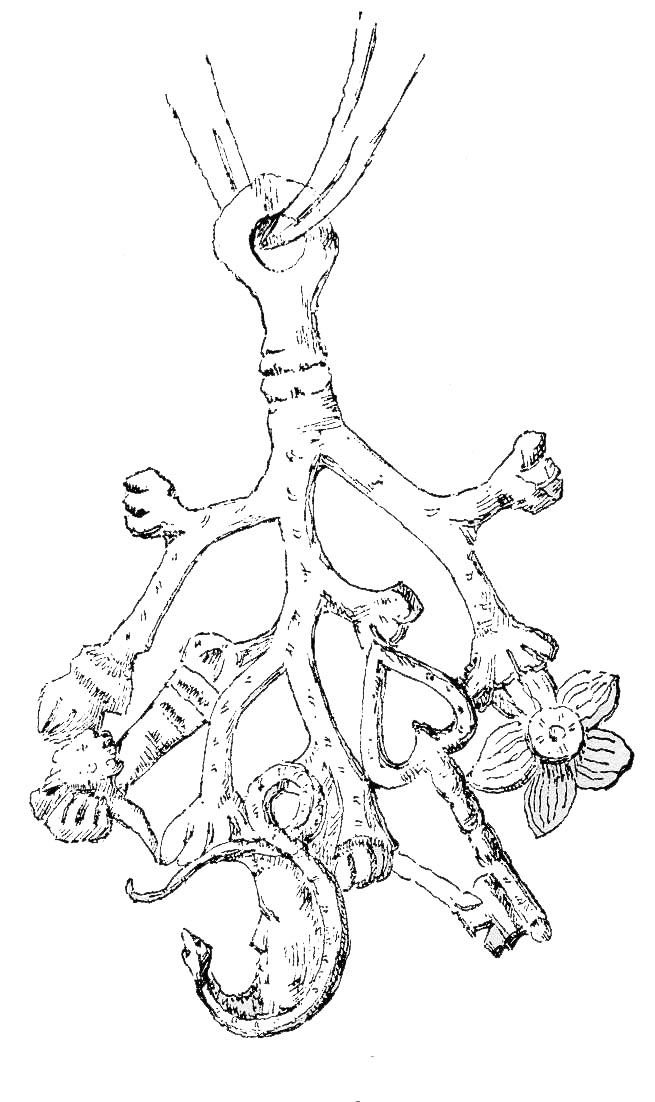

The component parts of the cimarute, which are particularly associated with Southern Italy, may differ by region of origin. From out of a central stalk of rue serving as its base, there radiate multiple branches which appear to blossom into various designs; the divergent branches "sprout" at their extremities such magical symbols as: a rose; a hand holding either a wand or a sword; a flaming heart; a fish; a crescent moon; a snake; an owl; a plumed medieval helmet; a vervain blossom; a dolphin; a cock; and an eagle. One cimaruta, for example, might bear the collective imagery of a key, dagger, blossom and moon. Most are double-sided and fairly large—some almost four inches in width.[2]

In Neopaganism

[edit]

Along with various other documented elements of regional magic traditions, the cimaruta is (alleged to be) in borrowed use amongst self-identified Italian-American witches. Some practitioners of the neopagan "religion of witchcraft" Stregoneria (or "Streghe") may consider it a remnant of a more ancient Italian magic tradition, such as that detailed by Charles Leland in his 1899 text Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches (which—apart from directly influencing the development of Stregheria—claimed the existence of an insular pagan witch-cult active in Italy).

Some modern versions of the cimaruta are cast in bronze or pewter.

Author Raven Grimassi in his book The Cimaruta: And Other Magical Charms From Old Italy (2012) discusses the charm as a sign of membership in the "Society of Diana" which he refers to as an organization of witches. Grimassi argues that the Cimaruta was originally a witchcraft charm used by witches that was later arrogated by Italian Folk Magic, and that Christian symbols were then added to the original Pagan symbols.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Cimaruta, Sirene, Tablets", from The Evil Eye (1895) by Frederick Thomas Elworthy (at sacred-texts.com)

- ^ Donald C. Watts (2007). Dictionary of Plant Lore. Academic Press. pp. 74, 332. ISBN 978-0080546025.

- Günther, R. T. (1905). "The Cimaruta: Its Structure and Development". Folk-lore. 16 (2). Folklore Society: 132–161. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1905.9719445. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- Grimassi, Raven (2012). The Cimaruta: And Other Magical Charms from Old Italy. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1479114009.

External links

[edit]Cimaruta

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Origins

Etymology

The term cimaruta derives from the Neapolitan dialect phrase cima di ruta, literally translating to "sprig" or "top" of rue, referring to a branch-like form mimicking the herb Ruta graveolens.[2][5] This nomenclature highlights the amulet's foundational link to the plant, which has been employed in Southern Italian folk remedies for its purported medicinal and protective qualities.[6] Linguistically, the word is embedded in Southern Italian dialects, particularly those of Campania, where "ruta" stems directly from the Latin rūta, itself borrowed from Ancient Greek ῥυτή (rhutḗ), denoting the bitter-tasting herb known for its aromatic and therapeutic properties.[7][8] The emphasis on the plant's symbolic role underscores the amulet's origins in herbal traditions that blend utility with superstition. In regional contexts across Campania and broader Southern Italy, the name has remained largely consistent, preserving its Neapolitan roots.[5]Historical Origins

The cimaruta's roots trace back to ancient Italic traditions, with possible antecedents in Etruscan, Roman, and Phoenician practices where rue (Ruta graveolens) played a central role in rituals for purification and protection.[2] Archaeological evidence includes an Iron Age Etruscan bronze amulet from the Bologna Museum, depicting a form resembling the cimaruta's branched structure, suggesting early use as a protective charm.[2] In Roman antiquity, rue was valued for its apotropaic properties against fascination and the evil eye, as noted by Pliny the Elder, who described its application in medicinal and ritual contexts to ward off 84 ailments, including spiritual afflictions.[2] This herb's association with lunar deities further linked it to protective rites, predating the amulet's formalized design.[4] The cimaruta emerged as a distinct folk amulet in Southern Italy, particularly in Naples and Campania, likely evolving from earlier pagan practices during or before the Renaissance, though its core form appears rooted in pre-Christian customs. Nineteenth-century ethnographies document its prevalence among lower classes in Naples, where it was worn by infants to avert the evil eye, as observed by travelers in the late 1800s.[2] Frederick Thomas Elworthy's 1895 study describes it as a composite charm derived from a simple rue sprig, adapted over time from ancient handheld protections into metal talismans.[2] Evidence from folk collections in the region highlights its continuity from medieval folk practices, blending herbal lore with symbolic additions.[4] Influenced by pagan Italic religions, the cimaruta drew from goddess worship, especially the cult of Diana Triformis—encompassing Diana, Hecate, and Proserpina—with its three-branched rue form symbolizing their threefold aspects of heaven, earth, and underworld.[2] Keys, associated with Hecate as guardian of thresholds, and other elements like crescents reflect these pre-Christian ties, as seen in Roman literary references to rue in Diana's sacred rites.[2] Christian syncretism later incorporated such pagan motifs, adapting them into broader protective amulets without fully erasing their Italic origins, a process evident in evolving designs from the medieval period onward.[4] Regional variations in origin stories center on Naples and Campania, where archaeological finds like third-century B.C. Greek vases from Capua depict similar protective motifs, supporting local development from ancient Italic bases.[2] Folk collections reveal distinct Neapolitan silver versions marked from the eighteenth century, contrasting with simpler rustic forms in provincial areas, underscoring the amulet's adaptation across Southern Italian communities.[4]Design and Symbolism

Physical Description

The cimaruta amulet is typically crafted from silver, a material chosen for its traditional associations with lunar protection and durability in folk artifacts.[4] Historical examples, such as those from Etruscan or ancient Italian contexts, have been made from bronze, while modern reproductions may occasionally use pewter or other alloys for affordability, though silver remains the standard for authenticity.[4][9] Structurally, the amulet takes the form of a stylized sprig of rue, featuring a central stalk that branches into three to five main arms arranged in a fan-like or cross-shaped pattern, often measuring approximately 3 inches in length and 2 inches in width to ensure compactness for personal wear or suspension.[4][9] The branches terminate in swellings resembling buds or seed pods, with additional charms—such as crescents, hands, or keys—attached via loops or integrated directly into the design, creating a double-sided, symmetrical composition suitable for hanging as a necklace or from an infant's bed.[4][10] Examples from museum collections, like a 19th-century silver piece in the Victoria and Albert Museum, illustrate this flat, branch-like form with a maximum height of 5 cm and depth of 0.2 cm, emphasizing its lightweight and portable nature.[9] In terms of construction, traditional cimaruta are hand-forged or cast in Italian workshops, with branches hammered or carved for detail and charms soldered or looped onto the framework, as seen in 18th-century silver artifacts from southern Italy.[4][10] Modern manufacturing often employs stamping techniques for the base metal, followed by the attachment of pre-molded symbolic elements, allowing for efficient production while preserving the amulet's intricate, organic silhouette; a suspension loop or hook is commonly incorporated at the top for practical wearability.[4]Symbolic Elements

The cimaruta's core motif is a stylized sprig of rue (Ruta graveolens), a herb long associated with warding off malice and the evil eye due to its bitter scent and reputed ability to counteract poisonous influences or spells.[2] The rue leaves themselves serve as the foundational apotropaic element, symbolizing protection and grace, with the amulet's branches extending from this central form to bear additional charms that amplify its magical potency.[1] These branches typically feature 3 to 7 charms, arranged symmetrically to balance and enhance the amulet's protective energies, often reflecting a triadic structure honoring the lunar goddess Diana in her threefold aspects as Selene (heavenly), Artemis (earthly), and Proserpina (underworldly).[2] Common symbols include:- Crescent moon: Representing Diana's lunar influence and her role as protector during childbirth, it counters malevolent gazes by invoking celestial safeguarding.[1]

- Key: Symbolizing unlocking secrets, fertility, or access to hidden realms, often with a heart-shaped bow alluding to phallic potency and Diana as opener of heaven's gates.[2]

- Hand (mano fico): Depicting the fig gesture to repel evil through insult or deflection, a direct counter to the evil eye's power.[4]

- Dagger or sword: Embodying defense and Diana as the huntress (Venatrix), used to symbolically strike down threats.[2]

- Fish: Signifying abundance and Diana-Proserpina's maritime aspects, or sometimes a horn for prosperity.[2]

- Snake: Linked to wisdom, renewal, and Proserpina's chthonic domain, often coiled around the crescent moon for transformative protection.[2]

- Flower (often rue or artemisia): Representing herbal magic and purification, as these plants were used in ancient rites for exorcism and healing.[1]

Cultural and Historical Significance

In Italian Folklore

In Southern Italian folklore, the cimaruta serves as a protective amulet deeply embedded in domestic rituals, particularly for safeguarding vulnerable family members. It is traditionally hung over cradles or worn around the neck of newborns to shield them from malocchio, the evil eye believed to cause misfortune or illness to infants.[11] Women also employ the cimaruta during pregnancy and childbirth, valuing its association with rue—a plant symbolizing fertility and safe delivery—to promote health and ease labor pains in everyday household practices.[11] The charm frequently integrates with other folk protections in Neapolitan and Campanian customs, where it is paired alongside cornicello horns or strands of garlic to amplify warding against negative influences. These combinations reflect a layered approach in traditional homes, with the cimaruta's branching rue form complementing the horn's phallic symbolism and garlic's purifying properties during rituals like blessing new arrivals or securing doorways.[5] Oral traditions in Southern Italy weave the cimaruta into tales of the "Old Religion," portraying it as a guardian rooted in pre-Christian beliefs, where the rue's bitter aroma is thought to repel malevolent spirits that threaten household harmony. Such stories emphasize its role in preserving family well-being through simple acts, like anointing the amulet with oil while reciting protective phrases to invoke ancestral safeguards.[5] Regionally, the cimaruta holds strong prevalence in areas like Abruzzo and Calabria, where variations include localized incantations spoken during its crafting or placement, often invoking blessings for prosperity and protection tailored to rural family life. In these communities, silversmiths inscribe personal motifs or adapt the charm's branches to local herbs, ensuring it aligns with distinct folk practices while maintaining its core apotropaic function.[11]Protection Against the Evil Eye

The concept of malocchio, or the evil eye, in Italian folklore refers to an involuntary or intentional curse believed to emanate from a person's gaze, causing misfortune, illness, or even death, with children being particularly vulnerable due to their perceived innocence and fragility.[12] This belief posits that envy or admiration can unwittingly transmit harmful energy, leading to symptoms such as unexplained fatigue, headaches, or sudden bad luck, often diagnosed through traditional methods like dropping olive oil into water to observe its dispersion pattern.[13] The cimaruta serves as a primary apotropaic amulet against this threat, traditionally worn by infants or hung above their beds to safeguard them from such malevolent influences.[1] The cimaruta's protective mechanism draws on the symbolic properties of rue (Ruta graveolens), whose inherent bitterness is thought to counteract the "sweetness" of envious glances, while the amulet's combined charms are believed to absorb, reflect, or deflect negative energy directed at the wearer.[2] In practice, the amulet is activated through rituals such as anointing it with olive oil—often blessed—to imbue it with purifying properties, or reciting protective prayers to invoke its power, ensuring it forms a barrier against the malocchio's insidious effects.[14] These practices emphasize the amulet's role not just as a passive talisman but as an active participant in warding off harm, particularly in regions like Naples and Abruzzi where high infant mortality was historically attributed to such curses amid poor living conditions.[1] Historical accounts from the 19th and early 20th centuries document the cimaruta's perceived efficacy in countering the evil eye, often used in tandem with diagnostic rituals like the oil-in-water test to confirm and mitigate affliction.[2] Frederick Thomas Elworthy's 1895 study describes its application among Neapolitan families, where the amulet's prophylactic qualities were credited with averting misfortune, drawing on ancient precedents traceable to Etruscan artifacts.[2] This efficacy was rooted in community testimonies rather than empirical evidence, highlighting its cultural persistence as a trusted defense.[13] The cimaruta embodies syncretic elements, blending pagan herbalism—such as rue's ancient associations with protection and the lunar goddess Diana—with Catholic invocations, where prayers to saints like the Madonna del Parto are recited alongside references to pre-Christian deities to amplify its spiritual potency.[2] This fusion reflects broader Italian folk traditions that integrate indigenous pagan roots with Christian rites, allowing the amulet to serve as a bridge between old herbal lore and formalized religious safeguards against the malocchio.[14]Association with Witchcraft and Religion

In Traditional Stregoneria

In traditional Italian folk magic practices, including elements of Stregoneria (vernacular witchcraft), the cimaruta served as a protective talisman against malevolent forces, such as the evil eye and witchcraft. Crafted to resemble a sprig of rue (Ruta graveolens), an herb revered for its apotropaic properties, the amulet incorporated symbolic elements believed to invoke protection in rituals for healing and warding. It was used in southern Italian regions like Campania and Calabria, where vernacular magic blended with folk healing traditions.[14] Charles G. Leland's 1899 work Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches provided the first scholarly documentation of the "Society of Diana," portrayed as a clandestine network of witches preserving ancient pagan rites centered on the goddess Diana and her daughter Aradia. While Leland's text, drawn from accounts by an informant named Maddalena, emphasizes incantations and spells without direct reference to the cimaruta, it established Stregoneria as a structured tradition of resistance against ecclesiastical oppression, later inspiring associations of the amulet with this society as a marker of initiatory knowledge.[15] However, scholarly perspectives emphasize that the cimaruta originated as a broader folk amulet for protection against the evil eye and witchcraft, rather than a specific tool of organized witch traditions.[16] [17] In the context of historical persecution, including the Inquisition's activities that waned by the early 18th century with informal accusations lingering into the mid-18th century, folk amulets like the cimaruta sometimes incorporated Christian motifs, such as saints or crosses, to blend into everyday Catholic life.[14][18]In Neopaganism

In Neopaganism, the cimaruta has been revived and adapted primarily within Stregheria, a modern reconstruction of Italian witchcraft, where it serves as a central emblem of the tradition's pagan heritage. Promoted by influential figures such as Raven Grimassi in his 2012 publication The Cimaruta: And Other Magical Charms From Old Italy, the amulet is positioned as a key symbol in Italian pagan reconstructionism, often interpreted as representing devotion to the goddess Diana and her cult.[19] Grimassi emphasizes its role in invoking protection and spiritual connection to pre-Christian deities, aligning it with Stregheria's efforts to reclaim ancient Italic spiritual practices.[20] Symbolic reinterpretation in Neopagan contexts focuses on restoring the cimaruta's perceived pre-Christian purity by emphasizing pagan elements and stripping away later Christian overlays, such as sacred heart motifs that were incorporated during the medieval period. Core symbols like the crescent moon (for Diana), the key (for Hecate), and the serpent (for Proserpina) are highlighted to evoke the triple aspect of the goddess, facilitating protection, invocation, and ritual empowerment.[20] In Stregheria initiations and altar setups, the cimaruta is employed to channel these energies, underscoring its function as a talisman for spiritual safeguarding and connection to the divine feminine.[19] Among Italian-American Neopagan communities, the cimaruta is commonly worn during rituals to embody membership in the "Old Religion," drawing on the narrative of ancient witch cults preserved in Charles Godfrey Leland's 1899 Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches, which portrays Diana as the central deity of Italian sorcery.[2] Practitioners integrate it into ceremonies for warding negativity and honoring ancestral pagan lineages, particularly in diaspora groups seeking cultural reconnection. However, debates persist regarding the cimaruta's authenticity as an exclusive witchcraft symbol; some scholars argue it originated as a broader folk magic amulet for protection against the evil eye, rather than a specific marker of organized witch traditions, viewing Neopagan claims as a romanticized reconstruction.[16] This perspective highlights its vernacular roots in Italian popular culture over specialized occult use.[17]Modern Usage

Contemporary Reproductions

In contemporary practice, cimaruta reproductions have largely transitioned to mass-produced forms using casting and stamping techniques, facilitating broader accessibility for tourists and general consumers. These items are typically crafted from silver or tin, materials chosen for their durability and traditional associations with protection.[4] Inferior stamped versions in silver predominate in modern manufacturing, often lacking the intricacy of historical pieces, while cast or hammered examples preserve more artisanal quality.[4] In southern Italian regions like Calabria, amulets incorporating the cimaruta motif continue to be fashioned from silver or tin as part of indigenous healing traditions.[21] Design adaptations in these reproductions frequently simplify the classic rue sprig structure for integration into jewelry, such as pendants and earrings, enhancing wearability as everyday accessories. Some versions feature stylized elements or substitute traditional symbols with hearts or other motifs to appeal to wider audiences, reflecting a degeneration from earlier elaborate forms.[4] Handmade artisanal cimaruta from Italian jewelers, such as those in Naples, retain closer fidelity to historical designs through lost-wax casting or hand-hammering.[22] Contemporary cimaruta are often worn as fashion statements or hung in homes for general spiritual safeguarding, with adaptations to modern aesthetics. Their use in Wiccan and Neopagan contexts is covered in the article's section on associations with witchcraft and religion. The global spread of the cimaruta accelerated among Italian diaspora communities and occult enthusiasts during the late 20th-century Neopagan revival, influencing international occult markets.[17][23]Collectibility and Commercial Availability

The cimaruta holds significant appeal in the antique market, particularly for 18th- and 19th-century silver examples originating from regions like Naples, where they were crafted as protective amulets. These pieces, often featuring intricate engravings and symbolic branches, are valued between $200 and $500 or more as of 2025, depending on condition, silver purity, and provenance, with rarer specimens from reputable auctions fetching higher prices.[24][25] For instance, a 19th-century silver cimaruta described as a post-medieval witch charm has appeared in auction listings, highlighting their collectible status among folk art enthusiasts.[24] In the broader commercial landscape, modern cimaruta reproductions are widely available online and in specialty shops, typically priced from $10 to $100 as of 2025 for silver-plated or sterling silver versions, with increased popularity on platforms like Amazon and Etsy. Occult and pagan supply stores provide similar items starting at around $13 for basic designs.[26][27] Authentic replicas from Italian artisans, including those inspired by Neapolitan traditions, can be found through brands like Fratelli Coppini, often sold for $80 to $120 in online marketplaces or specialty jewelers.[28][29] Several factors influence the value of cimaruta items in both antique and commercial contexts, including the rarity of regional variants such as those from Abruzzo, which may feature unique local engravings or motifs, as well as overall silver content and craftsmanship details. The growing interest from Neopagan communities has boosted demand, elevating prices for well-preserved or symbolically detailed pieces.[30] Examples held in institutions like the Science Museum Group underscore their historical rarity and cultural worth.[31] Ethical considerations are paramount when acquiring cimaruta, as modern reproductions must be distinguished from originals to avoid overpaying for fakes prevalent in Italian tourist markets. Buyers are advised to purchase from verified dealers or auction houses to ensure authenticity, as counterfeit versions often lack hallmarks or quality materials.[32]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ruta