Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Uniform polyhedron

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2011) |

In geometry, a uniform polyhedron has regular polygons as faces and is vertex-transitive—there is an isometry mapping any vertex onto any other. It follows that all vertices are congruent. Uniform polyhedra may be regular (if also face- and edge-transitive), quasi-regular (if also edge-transitive but not face-transitive), or semi-regular (if neither edge- nor face-transitive). The faces and vertices don't need to be convex, so many of the uniform polyhedra are also star polyhedra.

There are two infinite classes of uniform polyhedra, together with 75 other polyhedra. They are 2 infinite classes of prisms and antiprisms, the convex polyhedrons as in 5 Platonic solids and 13 Archimedean solids—2 quasiregular and 11 semiregular— the non-convex star polyhedra as in 4 Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra and 53 uniform star polyhedra—14 quasiregular and 39 semiregular. There are also many degenerate uniform polyhedra with pairs of edges that coincide, including one found by John Skilling called the great disnub dirhombidodecahedron, Skilling's figure.[1]

Dual polyhedra to uniform polyhedra are face-transitive (isohedral) and have regular vertex figures, and are generally classified in parallel with their dual (uniform) polyhedron. The dual of a regular polyhedron is regular, while the dual of an Archimedean solid is a Catalan solid.

The concept of uniform polyhedron is a special case of the concept of uniform polytope, which also applies to shapes in higher-dimensional (or lower-dimensional) space.

Definition

[edit]The Original Sin in the theory of polyhedra goes back to Euclid, and through Kepler, Poinsot, Cauchy and many others continues to afflict all the work on this topic (including that of the present author). It arises from the fact that the traditional usage of the term "regular polyhedra" was, and is, contrary to syntax and to logic: the words seem to imply that we are dealing, among the objects we call "polyhedra", with those special ones that deserve to be called "regular". But at each stage— Euclid, Kepler, Poinsot, Hess, Brückner, ... —the writers failed to define what are the "polyhedra" among which they are finding the "regular" ones.

Coxeter, Longuet-Higgins & Miller (1954) define uniform polyhedra to be vertex-transitive polyhedra with regular faces. They define a polyhedron to be a finite set of polygons such that each side of a polygon is a side of just one other polygon, such that no non-empty proper subset of the polygons has the same property. By a polygon they implicitly mean a polygon in 3-dimensional Euclidean space; these are allowed to be non-convex and intersecting each other.[2]

There are some generalizations of the concept of a uniform polyhedron. If the connectedness assumption is dropped, then we get uniform compounds, which can be split as a union of polyhedra, such as the compound of 5 cubes. If we drop the condition that the realization of the polyhedron is non-degenerate, then we get the so-called degenerate uniform polyhedra. These require a more general definition of polyhedra. Grünbaum (1994) gave a rather complicated definition of a polyhedron, while McMullen & Schulte (2002) gave a simpler and more general definition of a polyhedron: in their terminology, a polyhedron is a 2-dimensional abstract polytope with a non-degenerate 3-dimensional realization. Here an abstract polytope is a poset of its "faces" satisfying various condition, a realization is a function from its vertices to some space, and the realization is called non-degenerate if any two distinct faces of the abstract polytope have distinct realizations. Some of the ways they can be degenerate are as follows:

- Hidden faces. Some polyhedra have faces that are hidden, in the sense that no points of their interior can be seen from the outside. These are usually not counted as uniform polyhedra.

- Degenerate compounds. Some polyhedra have multiple edges and their faces are the faces of two or more polyhedra, though these are not compounds in the previous sense since the polyhedra share edges.

- Double covers. Some non-orientable polyhedra have double covers satisfying the definition of a uniform polyhedron. There double covers have doubled faces, edges and vertices. They are usually not counted as uniform polyhedra.

- Double faces. There are several polyhedra with doubled faces produced by Wythoff's construction. Most authors do not allow doubled faces and remove them as part of the construction.

- Double edges. Skilling's figure has the property that it has double edges (as in the degenerate uniform polyhedra) but its faces cannot be written as a union of two uniform polyhedra.

History

[edit]Regular convex polyhedra

[edit]- The Platonic solids date back to the classical Greeks and were studied by the Pythagoreans, Plato (c. 424 – 348 BC), Theaetetus (c. 417 BC – 369 BC), Timaeus of Locri (c. 420–380 BC), and Euclid (fl. 300 BC). The Etruscans discovered the regular dodecahedron before 500 BC.[3]

Nonregular uniform convex polyhedra

[edit]- The cuboctahedron was known by Plato.

- Archimedes (287 BC – 212 BC) discovered all of the 13 Archimedean solids. His original book on the subject was lost, but Pappus of Alexandria (c. 290 – c. 350 AD) mentioned Archimedes listed 13 polyhedra.

- Piero della Francesca (1415 – 1492) rediscovered the five truncations of the Platonic solids—truncated tetrahedron, truncated octahedron, truncated cube, truncated dodecahedron, and truncated icosahedron—and included illustrations and calculations of their metric properties in his book De quinque corporibus regularibus. He also discussed the cuboctahedron in a different book.[4]

- Luca Pacioli plagiarized Francesca's work in De divina proportione in 1509, adding the rhombicuboctahedron, calling it an icosihexahedron for its 26 faces, which was drawn by Leonardo da Vinci.

- Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) was the first to publish the complete list of Archimedean solids, in 1619. He also identified the infinite families of uniform prisms and antiprisms.

Regular star polyhedra

[edit]- Kepler (1619) discovered two of the regular Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra, the small stellated dodecahedron and great stellated dodecahedron.

- Louis Poinsot (1809) discovered the other two, the great dodecahedron and great icosahedron.

- The set of four was proven complete by Augustin-Louis Cauchy in 1813 and named by Arthur Cayley in 1859.

Other 53 nonregular star polyhedra

[edit]- Of the remaining 53, Edmund Hess (1878) discovered 2, Albert Badoureau (1881) discovered 36 more, and Pitsch (1881) independently discovered 18, of which 3 had not previously been discovered. Together these gave 41 polyhedra.

- The geometer H.S.M. Coxeter discovered the remaining twelve in collaboration with J. C. P. Miller (1930–1932) but did not publish. M.S. Longuet-Higgins and H.C. Longuet-Higgins independently discovered eleven of these. Lesavre and Mercier rediscovered five of them in 1947.

- Coxeter, Longuet-Higgins & Miller (1954) published the list of uniform polyhedra.

- Sopov (1970) proved their conjecture that the list was complete.

- In 1974, Magnus Wenninger published his book Polyhedron models, which lists all 75 nonprismatic uniform polyhedra, with many previously unpublished names given to them by Norman Johnson.

- Skilling (1975) independently proved the completeness and showed that if the definition of uniform polyhedron is relaxed to allow edges to coincide then there is just one extra possibility (the great disnub dirhombidodecahedron).

- In 1987, Edmond Bonan drew all the uniform polyhedra and their duals in 3D with a Turbo Pascal program called Polyca. Most of them were shown during the International Stereoscopic Union Congress held in 1993, at the Congress Theatre, Eastbourne, England; and again in 2005 at the Kursaal of Besançon, France.[5]

- In 1993, Zvi Har'El (1949–2008)[6] produced a complete kaleidoscopic construction of the uniform polyhedra and duals with a computer program called Kaleido and summarized it in a paper Uniform Solution for Uniform Polyhedra, counting figures 1-80.[7]

- Also in 1993, R. Mäder ported this Kaleido solution to Mathematica with a slightly different indexing system.[8]

- In 2002 Peter W. Messer discovered a minimal set of closed-form expressions for determining the main combinatorial and metrical quantities of any uniform polyhedron (and its dual) given only its Wythoff symbol.[9]

Uniform star polyhedra

[edit]

The 57 nonprismatic nonconvex forms, with exception of the great dirhombicosidodecahedron, are compiled by Wythoff constructions within Schwarz triangles.

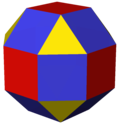

Convex forms by Wythoff construction

[edit]

The convex uniform polyhedra can be named by Wythoff construction operations on the regular form.

In more detail the convex uniform polyhedron are given below by their Wythoff construction within each symmetry group.

Within the Wythoff construction, there are repetitions created by lower symmetry forms. The cube is a regular polyhedron, and a square prism. The octahedron is a regular polyhedron, and a triangular antiprism. The octahedron is also a rectified tetrahedron. Many polyhedra are repeated from different construction sources, and are colored differently.

The Wythoff construction applies equally to uniform polyhedra and uniform tilings on the surface of a sphere, so images of both are given. The spherical tilings include the set of hosohedra and dihedra which are degenerate polyhedra.

These symmetry groups are formed from the reflectional point groups in three dimensions, each represented by a fundamental triangle (p q r), where p > 1, q > 1, r > 1 and 1/p + 1/q + 1/r < 1.

- Tetrahedral symmetry (3 3 2) – order 24

- Octahedral symmetry (4 3 2) – order 48

- Icosahedral symmetry (5 3 2) – order 120

- Dihedral symmetry (n 2 2), for n = 3,4,5,... – order 4n

The remaining nonreflective forms are constructed by alternation operations applied to the polyhedra with an even number of sides.

Along with the prisms and their dihedral symmetry, the spherical Wythoff construction process adds two regular classes which become degenerate as polyhedra : the dihedra and the hosohedra, the first having only two faces, and the second only two vertices. The truncation of the regular hosohedra creates the prisms.

Below the convex uniform polyhedra are indexed 1–18 for the nonprismatic forms as they are presented in the tables by symmetry form.

For the infinite set of prismatic forms, they are indexed in four families:

- Hosohedra H2... (only as spherical tilings)

- Dihedra D2... (only as spherical tilings)

- Prisms P3... (truncated hosohedra)

- Antiprisms A3... (snub prisms)

Summary tables

[edit]| Johnson name | Parent | Truncated | Rectified | Bitruncated (tr. dual) |

Birectified (dual) |

Cantellated | Omnitruncated (cantitruncated) |

Snub |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coxeter diagram | ||||||||

| Extended Schläfli symbol |

||||||||

| {p,q} | t{p,q} | r{p,q} | 2t{p,q} | 2r{p,q} | rr{p,q} | tr{p,q} | sr{p,q} | |

| t0{p,q} | t0,1{p,q} | t1{p,q} | t1,2{p,q} | t2{p,q} | t0,2{p,q} | t0,1,2{p,q} | ht0,1,2{p,q} | |

| Wythoff symbol (p q 2) |

q | p 2 | 2 q | p | 2 | p q | 2 p | q | p | q 2 | p q | 2 | p q 2 | | | p q 2 |

| Vertex figure | pq | q.2p.2p | (p.q)2 | p. 2q.2q | qp | p. 4.q.4 | 4.2p.2q | 3.3.p. 3.q |

| Tetrahedral (3 3 2) |

3.3.3 |

3.6.6 |

3.3.3.3 |

3.6.6 |

3.3.3 |

3.4.3.4 |

4.6.6 |

3.3.3.3.3 |

| Octahedral (4 3 2) |

4.4.4 |

3.8.8 |

3.4.3.4 |

4.6.6 |

3.3.3.3 |

3.4.4.4 |

4.6.8 |

3.3.3.3.4 |

| Icosahedral (5 3 2) |

5.5.5 |

3.10.10 |

3.5.3.5 |

5.6.6 |

3.3.3.3.3 |

3.4.5.4 |

4.6.10 |

3.3.3.3.5 |

And a sampling of dihedral symmetries:

(The sphere is not cut, only the tiling is cut.) (On a sphere, an edge is the arc of the great circle, the shortest way, between its two vertices. Hence, a digon whose vertices are not polar-opposite is flat: it looks like an edge.)

| (p 2 2) | Parent | Truncated | Rectified | Bitruncated (tr. dual) |

Birectified (dual) |

Cantellated | Omnitruncated (cantitruncated) |

Snub |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coxeter diagram | ||||||||

| Extended Schläfli symbol |

||||||||

| {p,2} | t{p,2} | r{p,2} | 2t{p,2} | 2r{p,2} | rr{p,2} | tr{p,2} | sr{p,2} | |

| t0{p,2} | t0,1{p,2} | t1{p,2} | t1,2{p,2} | t2{p,2} | t0,2{p,2} | t0,1,2{p,2} | ht0,1,2{p,2} | |

| Wythoff symbol | 2 | p 2 | 2 2 | p | 2 | p 2 | 2 p | 2 | p | 2 2 | p 2 | 2 | p 2 2 | | | p 2 2 |

| Vertex figure | p2 | 2.2p.2p | p. 2.p. 2 | p. 4.4 | 2p | p. 4.2.4 | 4.2p.4 | 3.3.3.p |

| Dihedral (2 2 2) |

{2,2} |

2.4.4 |

2.2.2.2 |

4.4.2 |

2.2 |

2.4.2.4 |

4.4.4 |

3.3.3.2 |

| Dihedral (3 2 2) |

3.3 |

2.6.6 |

2.3.2.3 |

4.4.3 |

2.2.2 |

2.4.3.4 |

4.4.6 |

3.3.3.3 |

| Dihedral (4 2 2) |

4.4 |

2.8.8 |  2.4.2.4 |

4.4.4 |

2.2.2.2 |

2.4.4.4 |

4.4.8 |

3.3.3.4 |

| Dihedral (5 2 2) |

5.5 |

2.10.10 |  2.5.2.5 |

4.4.5 |

2.2.2.2.2 |

2.4.5.4 |

4.4.10 |

3.3.3.5 |

| Dihedral (6 2 2) |

6.6 |

2.12.12 |

2.6.2.6 |

4.4.6 |

2.2.2.2.2.2 |

2.4.6.4 |

4.4.12 |

3.3.3.6 |

(3 3 2) Td tetrahedral symmetry

[edit]The tetrahedral symmetry of the sphere generates 5 uniform polyhedra, and a 6th form by a snub operation.

The tetrahedral symmetry is represented by a fundamental triangle with one vertex with two mirrors, and two vertices with three mirrors, represented by the symbol (3 3 2). It can also be represented by the Coxeter group A2 or [3,3], as well as a Coxeter diagram: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

There are 24 triangles, visible in the faces of the tetrakis hexahedron, and in the alternately colored triangles on a sphere:

| # | Name | Graph A3 |

Graph A2 |

Picture | Tiling | Vertex figure |

Coxeter and Schläfli symbols |

Face counts by position | Element counts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. 2 [3] (4) |

Pos. 1 [2] (6) |

Pos. 0 [3] (4) |

Faces | Edges | Vertices | ||||||||

| 1 | Tetrahedron |

|

|

|

|

|

{3,3} |

{3} |

4 | 6 | 4 | ||

| [1] | Birectified tetrahedron (same as tetrahedron) |

|

|

|

|

t2{3,3}={3,3} |

{3} |

4 | 6 | 4 | |||

| 2 | Rectified tetrahedron Tetratetrahedron (same as octahedron) |

|

|

|

|

t1{3,3}=r{3,3} |

{3} |

{3} |

8 | 12 | 6 | ||

| 3 | Truncated tetrahedron |

|

|

|

|

t0,1{3,3}=t{3,3} |

{6} |

{3} |

8 | 18 | 12 | ||

| [3] | Bitruncated tetrahedron (same as truncated tetrahedron) |

|

|

|

t1,2{3,3}=t{3,3} |

{3} |

{6} |

8 | 18 | 12 | |||

| 4 | Cantellated tetrahedron Rhombitetratetrahedron (same as cuboctahedron) |

|

|

|

|

t0,2{3,3}=rr{3,3} |

{3} |

{4} |

{3} |

14 | 24 | 12 | |

| 5 | Omnitruncated tetrahedron Truncated tetratetrahedron (same as truncated octahedron) |

|

|

|

|

|

t0,1,2{3,3}=tr{3,3} |

{6} |

{4} |

{6} |

14 | 36 | 24 |

| 6 | Snub tetratetrahedron (same as icosahedron) |

|

|

|

|

sr{3,3} |

{3} |

2 {3} |

{3} |

20 | 30 | 12 | |

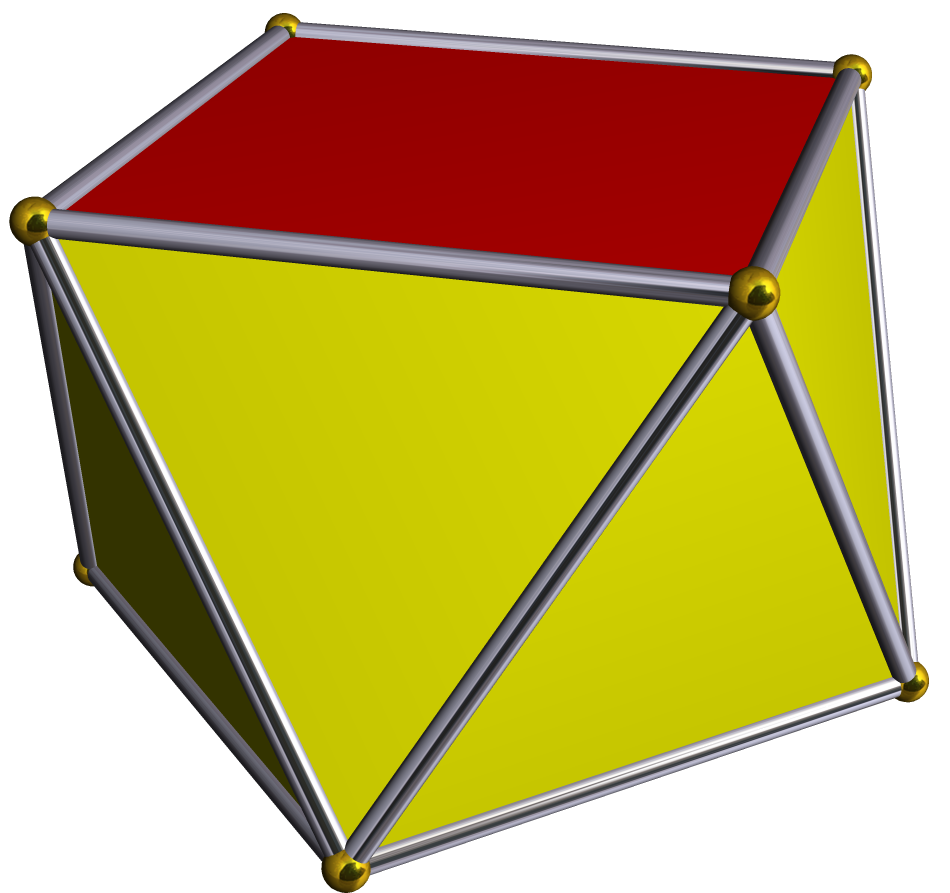

(4 3 2) Oh octahedral symmetry

[edit]The octahedral symmetry of the sphere generates 7 uniform polyhedra, and a 7 more by alternation. Six of these forms are repeated from the tetrahedral symmetry table above.

The octahedral symmetry is represented by a fundamental triangle (4 3 2) counting the mirrors at each vertex. It can also be represented by the Coxeter group B2 or [4,3], as well as a Coxeter diagram: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

There are 48 triangles, visible in the faces of the disdyakis dodecahedron, and in the alternately colored triangles on a sphere:

| # | Name | Graph B3 |

Graph B2 |

Picture | Tiling | Vertex figure |

Coxeter and Schläfli symbols |

Face counts by position | Element counts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. 2 [4] (6) |

Pos. 1 [2] (12) |

Pos. 0 [3] (8) |

Faces | Edges | Vertices | ||||||||

| 7 | Cube |

|

|

|

{4,3} |

{4} |

6 | 12 | 8 | ||||

| [2] | Octahedron |

|

|

|

|

|

{3,4} |

{3} |

8 | 12 | 6 | ||

| [4] | Rectified cube Rectified octahedron (Cuboctahedron) |

|

|

|

{4,3} |

{4} |

{3} |

14 | 24 | 12 | |||

| 8 | Truncated cube |

|

|

|

|

|

t0,1{4,3}=t{4,3} |

{8} |

{3} |

14 | 36 | 24 | |

| [5] | Truncated octahedron |

|

|

|

|

t0,1{3,4}=t{3,4} |

{4} |

{6} |

14 | 36 | 24 | ||

| 9 | Cantellated cube Cantellated octahedron Rhombicuboctahedron |

|

|

|

|

|

t0,2{4,3}=rr{4,3} |

{4} |

{4} |

{3} |

26 | 48 | 24 |

| 10 | Omnitruncated cube Omnitruncated octahedron Truncated cuboctahedron |

|

|

|

|

t0,1,2{4,3}=tr{4,3} |

{8} |

{4} |

{6} |

26 | 72 | 48 | |

| [6] | Snub octahedron (same as Icosahedron) |

|

|

|

|

= s{3,4}=sr{3,3} |

{3} |

{3} |

20 | 30 | 12 | ||

| [1] | Half cube (same as Tetrahedron) |

|

|

|

|

= h{4,3}={3,3} |

1/2 {3} |

4 | 6 | 4 | |||

| [2] | Cantic cube (same as Truncated tetrahedron) |

|

|

|

= h2{4,3}=t{3,3} |

1/2 {6} |

1/2 {3} |

8 | 18 | 12 | |||

| [4] | (same as Cuboctahedron) |

|

|

|

|

= rr{3,3} |

14 | 24 | 12 | ||||

| [5] | (same as Truncated octahedron) |

|

|

|

|

|

= tr{3,3} |

14 | 36 | 24 | |||

| [9] | Cantic snub octahedron (same as Rhombicuboctahedron) |

|

|

|

|

|

s2{3,4}=rr{3,4} |

26 | 48 | 24 | |||

| 11 | Snub cuboctahedron |

|

|

sr{4,3} |

{4} |

2 {3} |

{3} |

38 | 60 | 24 | |||

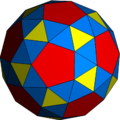

(5 3 2) Ih icosahedral symmetry

[edit]The icosahedral symmetry of the sphere generates 7 uniform polyhedra, and a 1 more by alternation. Only one is repeated from the tetrahedral and octahedral symmetry table above.

The icosahedral symmetry is represented by a fundamental triangle (5 3 2) counting the mirrors at each vertex. It can also be represented by the Coxeter group G2 or [5,3], as well as a Coxeter diagram: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

There are 120 triangles, visible in the faces of the disdyakis triacontahedron, and in the alternately colored triangles on a sphere:

| # | Name | Graph (A2) [6] |

Graph (H3) [10] |

Picture | Tiling | Vertex figure |

Coxeter and Schläfli symbols |

Face counts by position | Element counts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. 2 [5] (12) |

Pos. 1 [2] (30) |

Pos. 0 [3] (20) |

Faces | Edges | Vertices | ||||||||

| 12 | Dodecahedron |

|

|

|

|

{5,3} |

{5} |

12 | 30 | 20 | |||

| [6] | Icosahedron |

|

|

|

|

|

{3,5} |

{3} |

20 | 30 | 12 | ||

| 13 | Rectified dodecahedron Rectified icosahedron Icosidodecahedron |

|

|

|

t1{5,3}=r{5,3} |

{5} |

{3} |

32 | 60 | 30 | |||

| 14 | Truncated dodecahedron |

|

|

|

t0,1{5,3}=t{5,3} |

{10} |

{3} |

32 | 90 | 60 | |||

| 15 | Truncated icosahedron |

|

|

|

|

t0,1{3,5}=t{3,5} |

{5} |

{6} |

32 | 90 | 60 | ||

| 16 | Cantellated dodecahedron Cantellated icosahedron Rhombicosidodecahedron |

|

|

|

t0,2{5,3}=rr{5,3} |

{5} |

{4} |

{3} |

62 | 120 | 60 | ||

| 17 | Omnitruncated dodecahedron Omnitruncated icosahedron Truncated icosidodecahedron |

|

|

|

|

|

t0,1,2{5,3}=tr{5,3} |

{10} |

{4} |

{6} |

62 | 180 | 120 |

| 18 | Snub icosidodecahedron |

|

|

|

sr{5,3} |

{5} |

2 {3} |

{3} |

92 | 150 | 60 | ||

(p 2 2) Prismatic [p,2], I2(p) family (Dph dihedral symmetry)

[edit]The dihedral symmetry of the sphere generates two infinite sets of uniform polyhedra, prisms and antiprisms, and two more infinite set of degenerate polyhedra, the hosohedra and dihedra which exist as tilings on the sphere.

The dihedral symmetry is represented by a fundamental triangle (p 2 2) counting the mirrors at each vertex. It can also be represented by the Coxeter group I2(p) or [n,2], as well as a prismatic Coxeter diagram: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

Below are the first five dihedral symmetries: D2 ... D6. The dihedral symmetry Dp has order 4n, represented the faces of a bipyramid, and on the sphere as an equator line on the longitude, and n equally-spaced lines of longitude.

(2 2 2) Dihedral symmetry

[edit]There are 8 fundamental triangles, visible in the faces of the square bipyramid (Octahedron) and alternately colored triangles on a sphere:

| # | Name | Picture | Tiling | Vertex figure |

Coxeter and Schläfli symbols |

Face counts by position | Element counts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. 2 [2] (2) |

Pos. 1 [2] (2) |

Pos. 0 [2] (2) |

Faces | Edges | Vertices | ||||||

| D2 H2 |

Digonal dihedron, digonal hosohedron |

|

{2,2} |

{2} |

2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| D4 | Truncated digonal dihedron (same as square dihedron) |

|

t{2,2}={4,2} |

{4} |

2 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| P4 [7] |

Omnitruncated digonal dihedron (same as cube) |

|

|

|

t0,1,2{2,2}=tr{2,2} |

{4} |

{4} |

{4} |

6 | 12 | 8 |

| A2 [1] |

Snub digonal dihedron (same as tetrahedron) |

|

|

|

sr{2,2} |

2 {3} |

4 | 6 | 4 | ||

(3 2 2) D3h dihedral symmetry

[edit]There are 12 fundamental triangles, visible in the faces of the hexagonal bipyramid and alternately colored triangles on a sphere:

| # | Name | Picture | Tiling | Vertex figure |

Coxeter and Schläfli symbols |

Face counts by position | Element counts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. 2 [3] (2) |

Pos. 1 [2] (3) |

Pos. 0 [2] (3) |

Faces | Edges | Vertices | ||||||

| D3 | Trigonal dihedron |

|

{3,2} |

{3} |

2 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| H3 | Trigonal hosohedron |

|

{2,3} |

{2} |

3 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| D6 | Truncated trigonal dihedron (same as hexagonal dihedron) |

|

t{3,2} |

{6} |

2 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| P3 | Truncated trigonal hosohedron (Triangular prism) |

|

|

|

t{2,3} |

{3} |

{4} |

5 | 9 | 6 | |

| P6 | Omnitruncated trigonal dihedron (Hexagonal prism) |

|

|

|

t0,1,2{2,3}=tr{2,3} |

{6} |

{4} |

{4} |

8 | 18 | 12 |

| A3 [2] |

Snub trigonal dihedron (same as Triangular antiprism) (same as octahedron) |

|

|

|

sr{2,3} |

{3} |

2 {3} |

8 | 12 | 6 | |

| P3 | Cantic snub trigonal dihedron (Triangular prism) |

|

|

|

s2{2,3}=t{2,3} |

5 | 9 | 6 | |||

(4 2 2) D4h dihedral symmetry

[edit]There are 16 fundamental triangles, visible in the faces of the octagonal bipyramid and alternately colored triangles on a sphere:

| # | Name | Picture | Tiling | Vertex figure |

Coxeter and Schläfli symbols |

Face counts by position | Element counts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. 2 [4] (2) |

Pos. 1 [2] (4) |

Pos. 0 [2] (4) |

Faces | Edges | Vertices | ||||||

| D4 | square dihedron |

|

{4,2} |

{4} |

2 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| H4 | square hosohedron |

|

{2,4} |

{2} |

4 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| D8 | Truncated square dihedron (same as octagonal dihedron) |

t{4,2} |

{8} |

2 | 8 | 8 | |||||

| P4 [7] |

Truncated square hosohedron (Cube) |

|

|

|

t{2,4} |

{4} |

{4} |

6 | 12 | 8 | |

| D8 | Omnitruncated square dihedron (Octagonal prism) |

|

t0,1,2{2,4}=tr{2,4} |

{8} |

{4} |

{4} |

10 | 24 | 16 | ||

| A4 | Snub square dihedron (Square antiprism) |

|

|

|

sr{2,4} |

{4} |

2 {3} |

10 | 16 | 8 | |

| P4 [7] |

Cantic snub square dihedron (Cube) |

|

|

|

s2{4,2}=t{2,4} |

6 | 12 | 8 | |||

| A2 [1] |

Snub square hosohedron (Digonal antiprism) (Tetrahedron) |

|

|

|

s{2,4}=sr{2,2} |

4 | 6 | 4 | |||

(5 2 2) D5h dihedral symmetry

[edit]There are 20 fundamental triangles, visible in the faces of the decagonal bipyramid and alternately colored triangles on a sphere:

| # | Name | Picture | Tiling | Vertex figure |

Coxeter and Schläfli symbols |

Face counts by position | Element counts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. 2 [5] (2) |

Pos. 1 [2] (5) |

Pos. 0 [2] (5) |

Faces | Edges | Vertices | ||||||

| D5 | Pentagonal dihedron |

|

{5,2} |

{5} |

2 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| H5 | Pentagonal hosohedron |

|

{2,5} |

{2} |

5 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| D10 | Truncated pentagonal dihedron (same as decagonal dihedron) |

t{5,2} |

{10} |

2 | 10 | 10 | |||||

| P5 | Truncated pentagonal hosohedron (same as pentagonal prism) |

|

|

|

t{2,5} |

{5} |

{4} |

7 | 15 | 10 | |

| P10 | Omnitruncated pentagonal dihedron (Decagonal prism) |

|

|

t0,1,2{2,5}=tr{2,5} |

{10} |

{4} |

{4} |

12 | 30 | 20 | |

| A5 | Snub pentagonal dihedron (Pentagonal antiprism) |

|

|

|

sr{2,5} |

{5} |

2 {3} |

12 | 20 | 10 | |

| P5 | Cantic snub pentagonal dihedron (Pentagonal prism) |

|

|

|

s2{5,2}=t{2,5} |

7 | 15 | 10 | |||

(6 2 2) D6h dihedral symmetry

[edit]There are 24 fundamental triangles, visible in the faces of the dodecagonal bipyramid and alternately colored triangles on a sphere.

| # | Name | Picture | Tiling | Vertex figure |

Coxeter and Schläfli symbols |

Face counts by position | Element counts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. 2 [6] (2) |

Pos. 1 [2] (6) |

Pos. 0 [2] (6) |

Faces | Edges | Vertices | ||||||

| D6 | Hexagonal dihedron |

|

{6,2} |

{6} |

2 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| H6 | Hexagonal hosohedron |

|

{2,6} |

{2} |

6 | 6 | 2 | ||||

| D12 | Truncated hexagonal dihedron (same as dodecagonal dihedron) |

|

t{6,2} |

{12} |

2 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| H6 | Truncated hexagonal hosohedron (same as hexagonal prism) |

|

|

|

t{2,6} |

{6} |

{4} |

8 | 18 | 12 | |

| P12 | Omnitruncated hexagonal dihedron (Dodecagonal prism) |

|

|

|

t0,1,2{2,6}=tr{2,6} |

{12} |

{4} |

{4} |

14 | 36 | 24 |

| A6 | Snub hexagonal dihedron (Hexagonal antiprism) |

|

|

|

sr{2,6} |

{6} |

2 {3} |

14 | 24 | 12 | |

| P3 | Cantic hexagonal dihedron (Triangular prism) |

|

|

|

h2{6,2}=t{2,3} |

5 | 9 | 6 | |||

| P6 | Cantic snub hexagonal dihedron (Hexagonal prism) |

|

|

|

s2{6,2}=t{2,6} |

8 | 18 | 12 | |||

| A3 [2] |

Snub hexagonal hosohedron (same as Triangular antiprism) (same as octahedron) |

|

|

|

s{2,6}=sr{2,3} |

8 | 12 | 6 | |||

Wythoff construction operators

[edit]| Operation | Symbol | Coxeter diagram |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | {p,q} t0{p,q} |

Any regular polyhedron or tiling | |

| Rectified (r) | r{p,q} t1{p,q} |

The edges are fully truncated into single points. The polyhedron now has the combined faces of the parent and dual. Polyhedra are named by the number of sides of the two regular forms: {p,q} and {q,p}, like cuboctahedron for r{4,3} between a cube and octahedron. | |

| Birectified (2r) (also dual) |

2r{p,q} t2{p,q} |

| |

| Truncated (t) | t{p,q} t0,1{p,q} |

Each original vertex is cut off, with a new face filling the gap. Truncation has a degree of freedom, which has one solution that creates a uniform truncated polyhedron. The polyhedron has its original faces doubled in sides, and contains the faces of the dual.

| |

| Bitruncated (2t) (also truncated dual) |

2t{p,q} t1,2{p,q} |

A bitruncation can be seen as the truncation of the dual. A bitruncated cube is a truncated octahedron. | |

| Cantellated (rr) (Also expanded) |

rr{p,q} | In addition to vertex truncation, each original edge is beveled with new rectangular faces appearing in their place. A uniform cantellation is halfway between both the parent and dual forms. A cantellated polyhedron is named as a rhombi-r{p,q}, like rhombicuboctahedron for rr{4,3}.

| |

| Cantitruncated (tr) (Also omnitruncated) |

tr{p,q} t0,1,2{p,q} |

The truncation and cantellation operations are applied together to create an omnitruncated form which has the parent's faces doubled in sides, the dual's faces doubled in sides, and squares where the original edges existed. |

| Operation | Symbol | Coxeter diagram |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Snub rectified (sr) | sr{p,q} | The alternated cantitruncated. All the original faces end up with half as many sides, and the squares degenerate into edges. Since the omnitruncated forms have 3 faces/vertex, new triangles are formed. Usually these alternated faceting forms are slightly deformed thereafter in order to end again as uniform polyhedra. The possibility of the latter variation depends on the degree of freedom.

| |

| Snub (s) | s{p,2q} | Alternated truncation | |

| Cantic snub (s2) | s2{p,2q} | ||

| Alternated cantellation (hrr) | hrr{2p,2q} | Only possible in uniform tilings (infinite polyhedra), alternation of For example, | |

| Half (h) | h{2p,q} | Alternation of | |

| Cantic (h2) | h2{2p,q} | Same as | |

| Half rectified (hr) | hr{2p,2q} | Only possible in uniform tilings (infinite polyhedra), alternation of For example, | |

| Quarter (q) | q{2p,2q} | Only possible in uniform tilings (infinite polyhedra), same as For example, |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Diudea (2018), p. https://books.google.com/books?id=p_06DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA40 40].

- ^ Coxeter, Longuet-Higgins & Miller (1954).

- ^ Regular Polytopes, p.13

- ^ Piero della Francesca's Polyhedra

- ^ Edmond Bonan, "Polyèdres Eastbourne 1993", Stéréo-Club Français 1993

- ^ Dr. Zvi Har'El (December 14, 1949 – February 2, 2008) and International Jules Verne Studies - A Tribute

- ^ Har'el, Zvi (1993). "Uniform Solution for Uniform Polyhedra" (PDF). Geometriae Dedicata. 47: 57–110. doi:10.1007/BF01263494. Zvi Har'El, Kaleido software, Images, dual images

- ^ Mäder, R. E. Uniform Polyhedra. Mathematica J. 3, 48-57, 1993. [1]

- ^ Messer, Peter W. (2002). "Closed-Form Expressions for Uniform Polyhedra and Their Duals". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 27 (3): 353–375. doi:10.1007/s00454-001-0078-2.

References

[edit]- Brückner, M. Vielecke und vielflache. Theorie und geschichte.. Leipzig, Germany: Teubner, 1900. [2]

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald; Longuet-Higgins, M. S.; Miller, J. C. P. (1954). "Uniform polyhedra" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 246 (916): 401–450. Bibcode:1954RSPTA.246..401C. doi:10.1098/rsta.1954.0003. ISSN 0080-4614. JSTOR 91532. MR 0062446. S2CID 202575183.

- Diudea, M. V. (2018), Multi-shell Polyhedral Clusters, Carbon Materials: Chemistry and Physics, vol. 10, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64123-2, ISBN 978-3-319-64123-2

- Grünbaum, B. (1994), "Polyhedra with Hollow Faces", in Tibor Bisztriczky; Peter McMullen; Rolf Schneider; et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Polytopes: Abstract, Convex and Computational, Springer, pp. 43–70, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0924-6_3, ISBN 978-94-010-4398-4

- McMullen, Peter; Schulte, Egon (2002), Abstract Regular Polytopes, Cambridge University Press

- Skilling, J. (1975). "The complete set of uniform polyhedra". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 278 (1278): 111–135. Bibcode:1975RSPTA.278..111S. doi:10.1098/rsta.1975.0022. ISSN 0080-4614. JSTOR 74475. MR 0365333. S2CID 122634260.

- Sopov, S. P. (1970). "A proof of the completeness on the list of elementary homogeneous polyhedra". Ukrainskiui Geometricheskiui Sbornik (8): 139–156. MR 0326550.

- Wenninger, Magnus (1974). Polyhedron Models. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09859-5.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Uniform Polyhedron". MathWorld.

- Uniform Solution for Uniform Polyhedra

- The Uniform Polyhedra

- Virtual Polyhedra Uniform Polyhedra

- Uniform polyhedron gallery Archived 2016-10-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Uniform Polyhedron -- from Wolfram MathWorld Has a visual chart of all 75

Uniform polyhedron

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A uniform polyhedron is a three-dimensional geometric figure bounded by regular polygonal faces, where all edges are of equal length and all vertices are symmetrically equivalent under the polyhedron's symmetry group.[1] This equivalence means the symmetry group acts transitively on the vertices, ensuring that each vertex is surrounded by the same arrangement of faces, known as the vertex figure.[4] The faces may include star polygons (polygrams) in non-convex cases, but they must all be regular and meet edge-to-edge.[1] Vertex-transitivity implies that there exists an isometry of the polyhedron mapping any vertex to any other, preserving the local configuration of incident faces and edges.[1] This property guarantees that the polyhedron has a high degree of symmetry, with all vertices congruent and the vertex figures identical across the structure.[5] Consequently, the polyhedron can be inscribed in a sphere, with all vertices lying on its surface and the geometric center at the sphere's origin.[1] In contrast to regular polyhedra, such as the Platonic solids, where all faces are congruent identical regular polygons, uniform polyhedra permit a variety of regular polygonal face types as long as the arrangement at each vertex remains uniform.[5] For instance, the cube is a regular uniform polyhedron with all square faces, while the truncated tetrahedron is a non-regular convex uniform polyhedron featuring a mix of regular triangles and hexagons meeting three triangles and one hexagon at each vertex.[1] Formally, uniform polyhedra realize vertex-transitive (and typically edge-transitive) tilings of the sphere by regular polygons, where the tiling's symmetry ensures all vertices are indistinguishable and the faces form an isohedral covering in the dual sense.[1]Key Properties

Uniform polyhedra are characterized by having all faces as regular polygons, either convex or star polygons (polygrams), with every edge of equal length. This ensures a high degree of symmetry, where the arrangement of faces around each vertex is identical. The regularity of the faces contributes to the polyhedron's uniform edge lengths, distinguishing them from more general polyhedra where faces may vary in shape or size.[1] A key feature is the vertex configuration, denoted by a sequence of integers in parentheses representing the number of sides of the regular polygons meeting at each vertex in cyclic order. For example, the cuboctahedron has the vertex configuration (3.4.3.4), indicating alternating triangles and squares around each vertex. This notation encapsulates the local geometry at vertices, highlighting the isogonal nature—meaning all vertices are equivalent under the polyhedron's symmetry group. Convex uniform polyhedra satisfy the Euler characteristic χ = V - E + F = 2. For star polyhedra, the generalized form is d_v V - E + d_f F = 2D, where d_v is the vertex density, d_f the face density, and D the overall density, reflecting their spherical topology adjusted for self-intersections.[1] For star polyhedra, the overall density D measures the degree of self-intersection as the number of times the surface covers the underlying sphere. Face density d_f is the density of the individual regular star polygon faces, and vertex density d_v is the density of the vertex figures. The pentagrammic faces {5/2} of the great stellated dodecahedron, for instance, have a face density of 2. Vertex density d_v is the density of the vertex figure and contributes to the generalized Euler formula. Uniform polyhedra are isogonal by definition, and their duals are isohedral, meaning face-transitive with all faces equivalent under symmetry.[1]Historical Development

Ancient and Early Modern Contributions

The earliest known discussions of uniform polyhedra, specifically the five regular convex polyhedra now called Platonic solids, appear in ancient Greek philosophy and mathematics. In his dialogue Timaeus (c. 360 BCE), Plato described these solids—the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron—as the fundamental building blocks of the cosmos, associating the first four with the classical elements of fire, earth, air, and water, while assigning the dodecahedron to the universe itself.[6][7] These five Platonic solids were the only uniform polyhedra recognized in antiquity, with their regularity defined by identical regular polygonal faces and equivalent vertices.[8] Euclid formalized the mathematical foundations of these solids in his Elements (c. 300 BCE), particularly in Books XI–XIII, where he provided rigorous proofs of their existence, constructions within a sphere, and demonstrations that no other regular convex polyhedra are possible beyond these five.[9] Euclid's approach emphasized their geometric properties, such as the equality of faces, edges, and vertex figures, establishing a systematic basis for uniformity that influenced subsequent polyhedral studies.[10] During the early modern period, interest in non-regular uniform polyhedra emerged. In Harmonices Mundi (1619), Johannes Kepler expanded beyond the Platonic solids by identifying and describing 13 convex uniform polyhedra with regular faces but irregular vertex configurations, including the rhombicuboctahedron and snub cube, which he illustrated and analyzed in relation to cosmic harmony.[11][12] Kepler's work marked a key advancement in recognizing semiregular forms as a distinct class.[13] René Descartes contributed further in his unpublished manuscript De solidorum elementis (c. 1630s), where he attempted an early enumeration of polyhedra, deriving a formula relating vertices, faces, and angles—later recognized as a precursor to Euler's formula—and listing several Archimedean solids among convex polyhedra.[14][15] Descartes' efforts highlighted the challenges of systematic classification but laid groundwork for later enumerations by focusing on general polyhedral properties.[14]Modern Classifications and Expansions

In the early 19th century, Louis Poinsot extended the study of regular polyhedra by discovering two additional regular star polyhedra—the great dodecahedron and great icosahedron—in addition to the two identified by Kepler two centuries earlier, thereby completing the set of four Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra.[2] These non-convex forms maintained regular polygonal faces and vertex figures but introduced intersecting faces, challenging prior notions of regularity confined to convex Platonic solids.[2] Augustin-Louis Cauchy advanced the classification in 1812–1813 by proving the completeness of the four Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra as the only regular star polyhedra and by analyzing vertex figures to ensure consistent arrangement of regular faces around each vertex.[16] This approach shifted focus from mere facial regularity to holistic symmetry, providing a rigorous framework that encompassed both convex and star polyhedra.[16] By 1876, Edmund Hess conducted a systematic enumeration of convex uniform polyhedra beyond the Platonic solids, identifying 13 Archimedean solids characterized by regular polygonal faces of more than one type meeting identically at each vertex.[2] Hess's catalog highlighted these semi-regular forms, bridging the gap between the five Platonic solids and more complex configurations.[2] In 1881, Albert Badoureau identified 37 nonconvex uniform polyhedra, and Johann Pitsch discovered additional ones, bringing the total of known nonconvex examples to 41.[2] In the mid-20th century, H.S.M. Coxeter, building on earlier work from the 1930s in which he and J.C.P. Miller discovered the remaining 12 nonconvex uniform polyhedra, introduced the Wythoff construction as a generative method for uniform polyhedra using reflections in spherical triangles, leading to a comprehensive enumeration in collaboration with M.S. Longuet-Higgins and J.C.P. Miller.[2] Their 1954 catalog listed 75 finite uniform polyhedra, comprising the 5 Platonic solids, 13 Archimedean solids, 4 Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra, and 53 non-prismatic star polyhedra.[2] This enumeration was later proven complete in 1975 by John Skilling.[3] Twentieth-century expansions further incorporated infinite families of uniform prisms and antiprisms, as detailed by Coxeter and Miller, where regular n-gonal bases extend indefinitely along a prism axis or twist in antiprismatic fashion, maintaining vertex-transitivity for all n ≥ 3.[2] These families generalized finite forms to Euclidean space, emphasizing the boundless nature of uniform structures under prismatic symmetries.[2]Types of Uniform Polyhedra

Convex Uniform Polyhedra

Convex uniform polyhedra represent the non-intersecting subset of uniform polyhedra, characterized by their realization as bounded convex bodies in three-dimensional Euclidean space. These polyhedra feature regular polygonal faces and identical vertex figures, ensuring vertex-transitivity, while maintaining a density of 1 and positive orientation without self-intersections. They encompass both a finite collection of 18 distinct forms and infinite families parameterized by the number of sides in their bases.[2] The finite convex uniform polyhedra consist of the five Platonic solids and the thirteen Archimedean solids. Platonic solids are the regular polyhedra where all faces are congruent regular polygons and all vertices are equivalent, including the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron. Archimedean solids, in contrast, are vertex-transitive convex polyhedra composed of regular polygonal faces of two or more types, arranged identically at each vertex; examples include the truncated cube, which has eight triangular and six octagonal faces, and the icosidodecahedron, featuring twenty triangles and twelve pentagons. These 18 polyhedra were systematically classified as the complete set of finite convex uniforms excluding prismatic families.[2] Beyond the finite cases, convex uniform polyhedra include infinite families of uniform prisms and antiprisms, defined for any integer . A uniform prism consists of two parallel regular -gonal bases connected by rectangular lateral faces, with triangular lateral faces in the limiting case of yielding the triangular prism. Uniform antiprisms feature two parallel regular -gonal bases rotated relative to each other and connected by equilateral triangular lateral faces, providing a twisted variant that generalizes to higher ; notably, the triangular antiprism coincides with the octahedron, one of the Platonic solids. These families extend the convex uniforms indefinitely while preserving the core properties of regularity in faces and vertex equivalence.[2] The convexity of these polyhedra ensures they can be embedded in Euclidean space as solid objects with well-defined interiors, free from the self-intersections that characterize star polyhedra, and their density of 1 reflects the single-layered enclosure of space around any interior point. This structural integrity underpins their applications in geometry, crystallography, and architecture, where the balance of symmetry and diversity in face types allows for robust tiling and modeling.[2]Uniform Star Polyhedra

Uniform star polyhedra represent the non-convex subset of uniform polyhedra, distinguished by their self-intersecting faces or edges, which allow for regular polygonal or star polygonal components arranged uniformly around each vertex. These structures deviate from convex forms by permitting intersections that create more complex geometries, often resulting in densities greater than 1—a measure generalizing the winding number to quantify how many times the polyhedral surface encloses the interior space. For instance, in star polyhedra, a line from the center to infinity may intersect the surface multiple times, reflecting the retrogressive or overlapping nature of faces. This self-intersection enables higher topological complexity, such as effective genus greater than 0, while maintaining vertex-transitivity and regular face edges.[1][2] The most prominent uniform star polyhedra are the four regular ones, collectively termed the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra, identified by Johannes Kepler in 1619 and fully recognized by Louis Poinsot in 1810. These include the small stellated dodecahedron ({5/2, 5}), composed of 12 intersecting pentagrams with five meeting at each vertex and a density of 3; the great dodecahedron ({5, 5/2}), featuring 12 intersecting pentagons and also density 3; the great icosahedron ({3, 5/2}), with 20 intersecting triangles and density 7; and the great stellated dodecahedron ({5/2, 3}), made of 12 pentagrams with density 7. Each exemplifies how fractional Schläfli symbols denote star polygon faces, leading to intersections where face planes cross through the interior, yet preserving icosahedral symmetry.[17][18][19][20] In addition to these regular cases, 53 non-regular uniform star polyhedra exist, encompassing quasiregular forms, stellations of Platonic solids, and other non-regular forms with mixed regular and star faces. Examples include the great truncated dodecahedron, which combines decagonal and pentagrammic faces in an intersecting arrangement, and the octahemioctahedron, featuring hemispherical intersections of triangles and hexagons. These non-regular stars often exhibit varied intersection types, such as face-to-face crossings or edge retrogrades, where vertex figures wind oppositely to the faces. The complete enumeration of these 57 finite non-prismatic uniform star polyhedra was established through systematic symmetry analysis in the 20th century, contrasting sharply with the 18 convex uniform polyhedra by introducing self-intersections that enhance geometric density and visual depth without violating uniformity.[2][21]Construction Methods

Wythoff Construction

The Wythoff construction provides a systematic method for generating uniform polyhedra through the symmetries of a kaleidoscope defined by three mirrors meeting at angles , , and , where , , and are rational numbers greater than 1. This approach, utilizing the Wythoff symbol , positions an initial point at the incenter of the corresponding Schwarz triangle in the fundamental domain of the Coxeter group, and repeated reflections across the mirrors produce the complete set of vertices for the polyhedron.[22] The resulting polyhedron is vertex-transitive with regular polygonal faces, encompassing both convex and star varieties depending on the parameters. In this construction, the original vertex is placed at coordinates within the Coxeter group's representation, aligned with one of the symmetry axes, and the full vertex set is obtained by applying the group's reflection operations, which correspond to the mirrors of the kaleidoscope. This reflective process ensures that all vertices are equivalent under the symmetry group, yielding a uniform polyhedron whose faces and vertex figures are determined by the branching angles of the Schwarz triangle. For uniform polyhedra, the parameters , , and are such that , leading to spherical geometry and finite polyhedra; fractions in parameters allow for star polygons with density greater than 1. Infinite Euclidean families like prisms and antiprisms arise when the sum equals 1, while hyperbolic tilings (sum <1) generate infinite non-uniform structures.[22][23][2] Representative examples illustrate the notation's application: the Wythoff symbol generates the regular icosahedron, a convex Platonic solid with 20 triangular faces and vertex configuration , while produces the small stellated dodecahedron, a nonconvex Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron featuring 12 pentagrammic faces with density 3 and vertex configuration .[22][24][18] These constructions highlight how integer parameters with the bar after the first number yield convex forms like Platonic solids, and specific placements with fractions introduce star polygons through intersecting faces. The Wythoff construction is complete for the finite uniform polyhedra, systematically generating all 75 such polyhedra using the appropriate Schwarz triangles and mirror activations, excluding only infinite prismatic families. This method unifies the production of Platonic solids, Archimedean solids, prisms, antiprisms, and nonconvex stars under a single kaleidoscopic framework.[22][2]Kaleidoscopic Generation

Kaleidoscopic generation of uniform polyhedra relies on the action of finite Coxeter reflection groups, which are discrete groups generated by reflections across a set of planes that intersect to form a triangular fundamental domain known as a Schwarz triangle. These groups, such as the tetrahedral, octahedral, or icosahedral symmetries, are defined by their Coxeter diagrams, where edges represent the dihedral angles between adjacent reflection planes, with being positive integers determining the group's structure. The fundamental domain is the spherical triangle bounded by these planes, with vertex angles , , and for the corresponding face types in the uniform polyhedron.[25][22] To generate the vertices, a seed point is selected within or on the boundary of the fundamental domain, typically equidistant from a subset of the reflection planes corresponding to the vertex figure. The full set of vertices is then obtained by applying the entire group action—comprising all compositions of reflections—to this seed point, producing the orbit where is the Coxeter group and is the seed. This transitive action on the vertex set ensures that the resulting polyhedron is vertex-transitive, meaning all vertices are equivalent under the symmetry group.[25][22] The kaleidoscopic process guarantees isogonal symmetry for uniform polyhedra, as the regular faces meet at each vertex in the same configuration, with the reflections preserving edge lengths and face regularity across the orbit. For finite uniform polyhedra, the reflection planes tile the sphere, yielding bounded convex or star polyhedra like the Platonic solids. In contrast, infinite families, such as uniform prisms and antiprisms, arise from Euclidean tilings generated by affine Coxeter groups, where the fundamental domain tiles the plane instead of the sphere, leading to unbounded structures with translational symmetries.[25][22] Vertex coordinates are computed by solving for the seed point's position in the fundamental domain, often using iterative methods that satisfy angle sum conditions around the vertex, such as for face angles and for vertex density . These solutions employ ring or belt methods, which decompose the coordinate system into concentric rings or belts of vertices perpendicular to a symmetry axis, allowing exact algebraic positioning via relations like for side lengths. The full coordinates are then obtained by applying the group generators to propagate the seed across the orbit.[22]Enumeration and Symmetry

Tetrahedral and Octahedral Symmetries

The tetrahedral symmetry group Td, of order 24, is the full point group of the regular tetrahedron, consisting of rotations (subgroup A4 of order 12) and reflections. This symmetry produces 4 uniform polyhedra, all vertex-transitive with regular faces. These include the convex regular tetrahedron and truncated tetrahedron, as well as two non-convex hemipolyhedra. The Wythoff construction, using the fundamental Schwarz triangle with angles π/2, π/3, π/3, generates these polyhedra by placing a generating point in the triangle and reflecting to form the vertex figure.[1][23] The following table lists the uniform polyhedra under Td symmetry, with their Wythoff symbols and vertex configurations:| Wythoff symbol | Name | Vertex configuration |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2 3 | Regular tetrahedron | (3.3.3) |

| 2 3 | 3 | Truncated tetrahedron | (3.6.6) |

| 3/2 3 | 3 | Octahemioctahedron | (3.3/2.3/2) |

| 3/2 3 | 2 | Tetrahemihexahedron | (3.4.3/2) |

| Wythoff symbol | Name | Vertex configuration |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 2 3 | Regular octahedron | (3.3.3.3) |

| 3 | 2 4 | Cube | (4.4.4) |

| 2 | 3 4 | Cuboctahedron | (3.4.3.4) |

| 3 4 | 2 | Rhombicuboctahedron | (3.4.4.4) |

| | 2 3 4 | Snub cube | (3.3.3.3.4) |

| 2 3 4 | | Truncated cuboctahedron | (4.6.8) |

| 2 3 | 4 | Truncated cube | (3.8.8) |

| 2 4 | 3 | Truncated octahedron | (4.6.6) |

Icosahedral and Dihedral Symmetries

Uniform polyhedra exhibiting icosahedral symmetry belong to the full icosahedral rotation group of order 120, which includes reflections. This symmetry generates 51 distinct uniform polyhedra, encompassing both convex Archimedean solids and non-convex star polyhedra, all sharing the same vertex configuration under the group's action.[1] These include the regular dodecahedron and icosahedron, quasiregular icosidodecahedron, truncated and rhombicosidodecahedral forms, as well as stellated variants like the small stellated dodecahedron and snub dodecahedron. The icosahedral group is associated with the Coxeter diagram , reflecting its geometric construction via mirrors.[27] The following table summarizes selected uniform polyhedra under icosahedral symmetry (out of 51 total), including their Wythoff symbols and topological densities (where defined; density measures the winding of faces around a vertex, with 1 indicating convex). For a complete list, see MathWorld.[27][1]| Wythoff Symbol | Name | Density |

|---|---|---|

| Icosahedron | 1 | |

| Dodecahedron | 1 | |

| Icosidodecahedron | 1 | |

| Truncated icosahedron | 1 | |

| Truncated dodecahedron | 1 | |

| Rhombicosidodecahedron | 1 | |

| Truncated icosidodecahedron | 1 | |

| Snub dodecahedron | 1 | |

| Small ditrigonal icosidodecahedron | 2 | |

| Small icosicosidodecahedron | 2 | |

| Small snub icosicosidodecahedron | 2 | |

| Small dodecicosidodecahedron | 2 | |

| Small stellated dodecahedron | 3 | |

| Great dodecahedron | 3 | |

| Dodecadodecahedron | 3 | |

| Truncated great dodecahedron | 3 | |

| Rhombidodecadodecahedron | 3 | |

| Small rhombidodecahedron | 3 | |

| Snub dodecadodecahedron | 3 | |

| Ditrigonal dodecadodecahedron | 4 | |

| Great ditrigonal dodecicosidodecahedron | 4 | |

| Small ditrigonal dodecicosidodecahedron | 4 | |

| Icosidodecadodecahedron | 4 | |

| Icositruncated dodecadodecahedron | 4 | |

| Snub icosidodecadodecahedron | 4 |

| Wythoff Symbol | Name | Density | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Triangular prism | 1 | |

| 4 | Square prism (cube) | 1 | |

| 5 | Pentagonal prism | 1 | |

| 6 | Hexagonal prism | 1 |

Infinite Uniform Families

Prismatic Uniform Polyhedra

Prismatic uniform polyhedra form an infinite family of convex uniform polyhedra known as uniform n-gonal prisms, constructed by connecting two parallel regular n-gonal bases with n square lateral faces, where n ≥ 3. The cube, a Platonic solid, is included as the square prism (n=4).[28] Each vertex is surrounded by two squares and one n-gon, yielding the vertex configuration (4.4.n). For n=3, the triangular prism has two equilateral triangular bases and three square sides, while for n=4, it is the cube itself, with six square faces and vertex configuration (4.4.4).[28] These polyhedra exhibit dihedral symmetry of type D_{nh}, characterized by an n-fold principal rotation axis, n twofold axes perpendicular to it, and horizontal reflection planes.[29] The Wythoff symbol for a uniform n-gonal prism is 2 n | 2, reflecting its generation from a right-angled spherical triangle with angles π/2, π/n, and π/2 via the kaleidoscopic construction.[30] All such prisms are convex, as the regular bases and perpendicular square sides ensure no internal angles exceed 180 degrees.[28] The volume V of a uniform n-gonal prism with side length s and height h (distance between bases) is given by derived from the area of the regular n-gonal base multiplied by the height. For uniform prisms, h = s to ensure square lateral faces.[31]Antiprismatic Uniform Polyhedra

Antiprismatic uniform polyhedra form an infinite family characterized by their twisted prismatic geometry, where two parallel regular n-gonal bases (for n ≥ 3) are rotated relative to each other by an angle of π/n and connected by 2n equilateral triangular faces. The regular octahedron, a Platonic solid, is included as the uniform triangular antiprism (n=3).[32] This rotation distinguishes them from prismatic uniform polyhedra, resulting in a structure where each vertex meets four equilateral triangles and one n-gon, yielding the vertex configuration (3.3.3.3.n). These polyhedra exhibit dihedral symmetry of type D_{nd}, with order 4n, incorporating n-fold rotational symmetry along the axis joining the bases, n twofold rotation axes perpendicular to the principal axis, and additional improper rotations including n dihedral mirror planes. For odd n, the symmetry group includes an inversion center, ensuring the structures remain achiral overall. The Wythoff symbols for these uniform antiprisms are | 2 2 n for the standard density-1 forms, while alternates such as crossed antiprisms (with higher density) are represented by | 2 2 n/2.[22][32] All faces of uniform antiprisms are regular polygons, satisfying the condition for uniformity with identical vertices under the symmetry group. Chiral variants, known as snub antiprisms, arise from further operations that introduce handedness, lacking reflection symmetry and existing in left- and right-handed enantiomorphs; these are particularly notable for preserving the twisted topology while enhancing triangular face density. The volume of a uniform n-gonal antiprism with edge length is given by which for n=3 recovers the octahedron's volume .[33]References

- https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Definition:Uniform_Polyhedron