Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Valentinianism

View on Wikipedia |

Valentinianism was one of the major Gnostic Christian movements. Founded by Valentinus (b. c. 100 CE – d. c. 165 CE)[1] in the 2nd century, its influence spread widely, not just within the Roman Empire but also from northwest Africa to Egypt through to Asia Minor and Syria in the east.[2] Later in the movement's history, it broke into Eastern and a Western schools.[further explanation needed] The Valentinian movement remained active until the 4th century, declining after Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which established Nicene Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire.[3]

No evidence exists that Valentinus was labeled a heretic during his lifetime. Irenaeus of Lyons, who was the first patristic source to describe Valentinus's teachings—though likely incompletely and with a bias toward the time's proto-orthodox Christianity—did not finish his apologetic work Against Heresies until the latter 2nd century, likely sometime after Valentinus's death.[4][5][6] The rapid growth of the Valentinian Gnostic movement—named eponymously after Valentinus—after his death prompted early Christian thought leaders, such as Irenaeus and later Hippolytus of Rome, to write apologetic works against Valentinus and Valentinianism, which conflicted with proto-orthodox theology.[5] Because the proto-orthodox camp's leadership encouraged the destruction of Gnostic texts writ large, most textual evidence regarding Valentinian theology and practice comes from its critics—particularly Irenaeus, who was highly focused on refuting Valentinianism.[7]

History

[edit]Valentinus was born in approximately 100 AD and died in Alexandria circa 180 AD.[8] According to the Christian scholar Epiphanius of Salamis, he was born in Egypt and schooled in Alexandria, where the Gnostic Basilides was teaching. However, Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215), another Christian scholar and teacher, reports that Valentinus was taught by Theudas, a disciple of the apostle Paul.[9] He was reputed to be an extremely eloquent man who possessed a great deal of charisma and had an innate ability to attract people.[10] He went to Rome some time between AD 136 and 140, in the time of Pope Hyginus, and had risen to the peak of his teaching career between AD 150 and 155, during the time of Pius.[11]

For some time in the mid-2nd century he was even a prominent and well-respected member of the proto-orthodox community in Rome. At one point during his career he had even hoped to attain the office of bishop, and apparently it was after he was passed over for the position that he broke from the Catholic Church.[9] Valentinus was said to have been a prolific writer; however, the only surviving remains of his work come from quotes that have been transmitted by Clement of Alexandria, Hippolytus and Marcellus of Ancyra. Most scholars also believe that Valentinus wrote the Gospel of Truth, one of the Nag Hammadi texts.[8]

Notable Valentinians included Heracleon (fl. ca. 175), Ptolemy, Florinus, Axionicus and Theodotus.

The Valentinian system

[edit]The theology that Irenaeus attributed to Valentinus is extremely complicated and difficult to follow. There is some skepticism among scholars that the system actually originated with him, and many believe that the system Irenaeus was counteracting was the construct of later Valentinians.

Synopsis

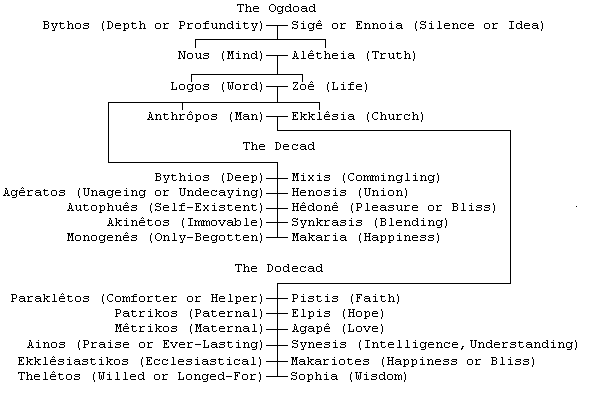

[edit]According to Irenaeus, the Valentinians believed that at the beginning there was a Pleroma (literally, a 'fullness'). At the centre of the Pleroma was the primal Father or Bythos, the beginning of all things who, after ages of silence and contemplation, emanated thirty Aeons, heavenly archetypes representing fifteen syzygies or sexually complementary pairs. Among them was Sophia. According to the symbolic narrative, Sophia's weakness, curiosity and passion led to her fall from the Pleroma and the creation of the world and man, both of which are flawed. Valentinians identified the god of the Old Testament to occasionally be the Demiurge,[12] the imperfect creator of the material world.

Man, the highest being in this material world, participates in both the spiritual and the material nature. The work of redemption consists in freeing the former from the latter. One needed to recognize the Father, the depth of all being, as the true source of divine power in order to achieve gnosis (knowledge).[13] The Valentinians believed that the attainment of this knowledge by the human individual had positive consequences within the universal order and contributed to restoring that order,[14] and that gnosis assists and complements faith, the key to salvation. Clement wrote that the Valentinians regarded Catholic Christians "as simple people to whom they attributed faith, while they think that gnosis is in themselves. Through the excellent seed that is to be found in them, they are by nature redeemed, and their gnosis is as far removed from faith as the spiritual from the physical".[15]

Aeons

[edit]The superstructure of the celestial system, the celestial world of Aeons, is summarized.[16] The Aeons are considered part of God, or the Monad, and belong to the purely ideal, noumenal, intelligible, or supersensible world; they are immaterial, they are hypostatic ideas. Together with the source from which they emanate they form the Pleroma. The transition from the immaterial to the material, from the noumenal to the sensible, is brought about by a flaw, or a passion, or a sin, in the female Aeon Sophia.

Epiphanius alleges that the Valentinians "set forth their thirty aeons in mythologic fashion, thinking that they conformed to the years of Jesus".[17] Of the eight celestial beings of the Ogdoad, four are peculiar to the Valentinian system. The third pair of Aeons, Logos and Zoe, occur only here, and the place of this pair is not firmly established, and occur sometimes before and sometimes after the fourth pair of Aeons, the Anthropos and the Ekklesia. We cannot be far wrong in suspecting that Valentinus was influenced by the prologue of the fourth Gospel (we also find the probably Johannine names Monogenes and Parakletos in the series of Aeons).[18]

Sophia

[edit]In Valentinianism, Sophia always stands absolutely at the center of the system, and in some sense she seems to represent the supreme female principle.

Sophia is the youngest of the Aeons. Observing the multitude of Aeons and the power of begetting them, she hurries back into the depth of the Father, and seeks to emulate him by producing offspring without assistance of her male half of the syzygy, but only projects an abortion, a formless substance. Upon this she is cast out of Pleroma and into the primal sub-stratum of matter.[19] In the Valentinian systems, the fall of Sophia appears in double guise. The higher Sophia still remains within the upper world after creating a disturbance, and after her expiation and repentance; but her premature offspring, Sophia Achamoth, is removed from the Pleroma, and becomes the heroine of the rest of the drama.[18] This fallen Sophia becomes a world creative power.

Sophia Achamoth, or "Lower Wisdom", the daughter of "Higher Wisdom", becomes the mother of the Demiurge, identified with the God of the Old Testament.

The Gnostics are children of Sophia; from her the heavenly seed, the divine spark, descended into this lower world, subject to the Heimarmene (destiny) and in the power of hostile spirits and powers; and all their sacraments and mysteries, their formulae and symbols, must be in order to find the way upwards, back to the highest heaven. This idea that the Gnostics know themselves to be in a hostile and evil world is reflected in the conception of Sophia. She became likewise a fallen Aeon, who has sunk down into the material world and seeks to free herself from it, receiving her liberation at the hands of a heavenly Redeemer, exactly like the Gnostics.[20]

Anthropos

[edit]The chief influence at work here seems to have been the idea of the celestial Anthropos (i.e. the Primal Man) – of whom the myth originally relates that he has sunk into matter and then raised himself up from it again – which appears in its simple form in individual Gnostic systems, e.g. in Poimandres (in the Corpus Hermeticum) and in Manichaeism.[20]

According to Valentinus,[21] the Anthropos no longer appears as the world-creative power sinking down into the material world, but as a celestial Aeon of the upper world, who stands in a clearly defined relationship to the fallen Aeon.[20] Adam was created in the name of Anthropos, and overawes the demons by the fear of the pre-existent man. This Anthropos is a cosmogonic element, pure mind as distinct from matter, mind conceived hypostatically as emanating from God and not yet darkened by contact with matter. This mind is considered as the reason of humanity, or humanity itself, as a personified idea, a category without corporeality, the human reason conceived as the World-Soul.[citation needed] It is possible that the role of the Anthropos is here transferred to Sophia Achamoth.[20]

It is also clear why the Ekklesia appears together with the Anthropos. With this is associated the community of the faithful and the redeemed, who are to share the same fate with him. Perfect gnosis (and thus the whole body of Gnostics) is connected with the Anthropos.[18][22]

Christ

[edit]Sophia conceives a passion for the First Father himself, or rather, under pretext of love she seeks to draw near to the unattainable Bythos, the Unknowable, and to comprehend his greatness. She brings forth, through her longing for that higher being, an Aeon who is higher and purer than herself, and at once rises into the celestial Aeons. Christ has pity on the abortive substance born of Sophia and gives it essence and form, whereupon Sophia tries to rise again to the Father, but in vain. In the enigmatic figure of Christ we again find hidden the original conception of the Primal Man, who sinks down into matter but rises again.[18]

In the fully developed Ptolemaean system we find a kindred conception, but with a slight difference. Here Christ and Sophia appear as a syzygy, with Christ representing the higher and Sophia the lower element. When this world has been born from Sophia in consequence of her passion, two Aeons, Nous (mind) and Aletheia (truth), by command of the Father, produce two new Aeons, Christ and the Holy Ghost; these restore order in the Pleroma, and in consequence all Aeons combine their best and most wonderful qualities to produce a new Aeon (Jesus, Logos, Soter, or Christ), the "First Fruits" whom they offer to the Father. And this celestial redeemer-Aeon now enters into a marriage with the fallen Aeon; they are the "bride and bridegroom". It is boldly stated in the exposition in Hippolytus' Philosophumena that they produce between them 70 celestial angels.[23]

This myth can be connected with the historic Jesus of Nazareth by further relating that Christ, having been united to the Sophia, descends into the earthly Jesus, the son of Mary.[20]

Horos

[edit]A figure entirely peculiar to Valentinian Gnostic thought is that of Horos (the Limiter). The name is perhaps an echo of the Egyptian Horus.[18][24]

The task of Horos is to separate the fallen Aeons from the upper world of Aeons. At the same time he becomes a kind of world-creative power, who in this capacity helps to construct an ordered world out of Sophia and her passions. He is also called Stauros (cross), and we frequently meet with references to the figure of Stauros. Speculations about the Stauros are older than Christianity, and a Platonic conception may have been at work here. Plato had already stated that the World-Soul revealed itself in the form of the letter chi (Χ), by which he meant that figure described in the heavens by the intersecting orbits of the sun and the planetary ecliptic. Since through this double orbit all the movements of the heavenly powers are determined, so all "becoming" and all life depend on it, and thus we can understand the statement that the World-Soul appears in the form of a Χ, or a cross.[18]

The cross can also stand for the wondrous Aeon on whom depends the ordering and life of the world, and thus Horos-Stauros appears here as the first redeemer of Sophia from her passions, and as the orderer of the creation of the world which now begins. Naturally, then, the figure of Horos-Stauros was often assimilated to that of the Christian Redeemer.[18] We possibly find echoes of this in the Gospel of Peter, where the Cross itself is depicted as speaking and even floating out of the tomb.[citation needed]

Monism

[edit]Peculiarly Valentinian is the above-mentioned derivation of the material world from the passions of Sophia. Whether this already formed part of the original system of Valentinus is questionable, but at any rate it plays a prominent part in the Valentinian school, and consequently appears with the most diverse variations in the account given by Irenaeus. By it is effected the comparative monism of the Valentinian system, and the dualism of the conception of two separate worlds of light and darkness is overcome:[18]

This collection [of passions] … was the substance of the matter from which this world was formed. From [her desire of] returning [to him who gave her life], every soul belonging to this world, and that of the Demiurge himself, derived its origin. All other things owed their beginning to her terror and sorrow. For from her tears all that is of a liquid nature was formed; from her smile all that is lucent; and from her grief and perplexity all the corporeal elements of the world.[25]

Demiurge

[edit]This derivation of the material world from the passions of the fallen Sophia is next affected by an older theory, which probably occupied an important place in the main Valentinian system. According to this theory the son of Sophia, whom she forms on the model of the Christ who has disappeared in the Pleroma, becomes the Demiurge, who with his angels now appears as the real-world creative power.[18]

According to the older conception, he was an evil and malicious offspring of his mother, who has already been deprived of any particle of light.[21][failed verification] In the Valentinian systems, the Demiurge was the offspring of a union of Sophia Achamoth with matter, and appears as the fruit of Sophia's repentance and conversion.[18] But as Achamoth herself was only the daughter of Sophia, the last of the thirty Aeons, the Demiurge was distant by many emanations from the Supreme God. The Demiurge in creating this world out of Chaos was unconsciously influenced for good by Christ; and the universe, to the surprise even of its Maker, became almost perfect. The Demiurge regretted even its slight imperfection, and as he thought himself the Supreme God, he attempted to remedy this by sending a Messiah. To this Messiah, however, was actually united Christ the Saviour, who redeemed men.

Creation of Man

[edit]With the doctrine of the creation of the world is connected the subject of the creation of man. According to it, the world-creating angels – not one, but many – create man, but the seed of the spirit comes into their creature without their knowledge, by the agency of a higher celestial Aeon, and they are then terrified by the faculty of speech by which their creature rises above them and try to destroy him.[18]

It is significant that Valentinus himself is credited with having written a treatise upon the threefold nature of man,[26] who is represented as at once spiritual, psychical, and material. In accordance with this there also arise three classes of men: the pneumatici, the psychici, and the hylici.[18] This doctrine dates at least as far back as Plato's Republic.

- The first, the material, will return to the grossness of matter and finally be consumed by fire.

- The second, or psychical, together with the Demiurge as their master, will enter a middle state, neither heaven (Pleroma) nor hell (matter).

- The third, the purely spiritual men will be completely freed from the influence of the Demiurge and together with the Saviour and Achamoth, his spouse, will enter the Pleroma divested of body and soul.

However, it is not a unanimous belief that material or psychical people were hopeless. Some have argued from the existent sources that humans could reincarnate in any of the three times, therefore a material or psychical person might have the chance to reborn in a future lifetime as a spiritual one.[27]

We also find ideas that emphasize the distinction between the soma psychikon and the soma pneumatikon:

Perfect redemption is the cognition itself of the ineffable greatness: for since through ignorance came about the defect … the whole system springing from ignorance is dissolved in gnosis. Therefore gnosis is the redemption of the inner man; and it is not of the body, for the body is corruptible; nor is it psychical, for even the soul is a product of the defect and it is a lodging to the spirit: pneumatic (spiritual) therefore also must be redemption itself. Through gnosis, then, is redeemed the inner, spiritual man: so that to us suffices the gnosis of universal being: and this is the true redemption.[28]

Soteriology

[edit]Salvation is not merely individual redemption of each human soul; it is a cosmic process. It is the return of all things to what they were before the flaw in the sphere of the Aeons brought matter into existence and imprisoned some part of the Divine Light into the evil Hyle (matter). This setting free of the light sparks is the process of salvation; when all light shall have left Hyle, it will be burnt up and destroyed.

In Valentinianism the process is extraordinarily elaborate, and we find here developed particularly clearly the myth of the heavenly marriage.[29] This myth, as we shall see more fully below, and as may be mentioned here, is of great significance for the practical piety of the Valentinian Gnostics. It is the chief idea of their pious practices mystically to repeat the experience of this celestial union of the Saviour with Sophia. In this respect, consequently, the myth underwent yet wider development. Just as the Saviour is the bridegroom of Sophia, so the heavenly angels, who sometimes appear as the sons of the Saviour and Sophia, sometimes as the escort of the Saviour, are the males betrothed to the souls of the Gnostics, which are looked upon as feminine. Thus every Gnostic had her unfallen counterpart standing in the presence of God, and the object of a pious life was to bring about and experience this inner union with the celestial abstract personage. This leads us straight to the sacramental ideas of this branch of Gnosticism (see below). And it also explains the expression used of the Gnostics in Irenaeus,[30] that they always meditate upon the secret of the heavenly union (the Syzygia).[23]

"The final consummation of all things will take place when all that is spiritual has been formed and perfected by gnosis."[31]

Gnosis

[edit]The central point of the piety of Valentinus seems to have been that mystical contemplation of God; in a letter preserved in Clement of Alexandria,[32] he sets forth that the soul of man is like an inn, which is inhabited by many evil spirits.

But when the Father, who alone is good, looks down and around him, then the soul is hallowed and lies in full light, and so he who has such a heart as this is to be called happy, for he shall behold God.[33]

But this contemplation of God, as Valentinus declares, closely and deliberately following the doctrines of the Church and with him the compiler of the Gospel of John, is accomplished through the revelation of the Son. This mystic also discusses a vision which is preserved in the Philosophumena of Hippolytus:[33]

Valentinus … had seen an infant child lately born; and questioning (this child), he proceeded to inquire who it might be. And (the child) replied, saying that he himself is the Logos, and then subjoined a sort of tragic legend...[34]

With celestial enthusiasm Valentinus here surveys and depicts the heavenly world of Aeons, and its connection with the lower world. Exalted joy of battle and a valiant courage breathe forth in the sermon in which Valentinus addresses the faithful:

Ye are from the beginning immortal and children of eternal life, and desire to divide death amongst you like a prey, in order to destroy it and utterly to annihilate it, that thus death may die in you and through you, for if ye dissolve the world, and are not yourselves dissolved, then are ye lords over creation and over all that passes away.[33][35]

Sacraments

[edit]The authorities for the sacramental practices of the Valentinians are preserved especially in the accounts of the Marcosians given in Irenaeus i. 13 and 20, and in the last section of Clement of Alexandria's Excerpta ex Theodoto.[33]

In almost all the sacramental prayers of the Gnostics handed down to us by Irenaeus, the Mother is the object of the invocation. There are moreover various figures in the fully developed system of the Valentinians who are in the Gnostic's mind when he calls upon the Mother; sometimes it is the fallen Achamoth, sometimes the higher Sophia abiding in the celestial world, sometimes Aletheia, the consort of the supreme heavenly father, but it is always the same idea, the Mother, on whom the faith of the Gnostics is fixed. Thus a baptismal confession of faith of the Gnostics[36] runs:

In the name of the unknown Father of all, by Aletheia, the Mother of all, by the name which descended upon Jesus.[33]

Bridal Chamber

[edit]

The chief sacrament of the Valentinians seems to have been that of the bridal chamber (nymphon).[33] The Gospel of Philip, a probable Valentinian text, reads:

There were three buildings specifically for sacrifice in Jerusalem. The one facing the west was called "The Holy". Another, facing south, was called "The Holy of the Holy". The third, facing east, was called "The Holy of the Holies", the place where only the high priest enters. Baptism is "the Holy" building. Redemption is the "Holy of the Holy". "The Holy of the Holies" is the bridal chamber. Baptism includes the resurrection and the redemption; the redemption (takes place) in the bridal chamber.

As Sophia was united with the Saviour, her bridegroom, so the faithful would experience a union with their angel in the Pleroma (cf. the "Higher Self" or "Holy Guardian Angel"). The ritual of this sacrament is briefly indicated: "A few of them prepare a bridal chamber and in it go through a form of consecration, employing certain fixed formulae, which are repeated over the person to be initiated, and stating that a spiritual marriage is to be performed after the pattern of the higher Syzygia."[36] Through a fortunate chance, a liturgical formula which was used at this sacrament appears to be preserved, though in a garbled form and in an entirely different connection, the author seeming to have been uncertain as to its original meaning. It runs:

I will confer my favor upon thee, for the father of all sees thine angel ever before his face ... we must now become as one; receive now this grace from me and through me; deck thyself as a bride who awaits her bridegroom, that thou mayest become as I am, and I as thou art. Let the seed of light descend into thy bridal chamber; receive the bridegroom and give place to him, and open thine arms to embrace him. Behold, grace has descended upon thee.[37][38]

Baptism

[edit]Besides this the Gnostics already practiced baptism, using the same form in all essentials as that of the Christian Church. The name given to baptism, at least among certain bodies, was apolytrosis (liberation); the baptismal formulae have been mentioned above.[37]

The Gnostics are baptized in the mysterious name which also descended upon Jesus at his baptism.[clarification needed] The angels of the Gnostics have also had to be baptized in this name, in order to bring about redemption for themselves and the souls belonging to them.[37][39]

In the baptismal formulae the sacred name of the Redeemer is mentioned over and over again. In one of the formulae occur the words: "I would enjoy thy name, Saviour of Truth." The concluding formula of the baptismal ceremony is: "Peace over all upon whom the Name rests."[36] This name pronounced at baptism over the faithful has above all the significance that the name will protect the soul in its ascent through the heavens, conduct it safely through all hostile powers to the lower heavens, and procure it access to Horos, who frightens back the lower souls by his magic word.[39] And for this life also baptism, in consequence of the pronouncing of the protecting name over the baptized person, accomplishes his liberation from the lower daemonic powers. Before baptism the Heimarmene is supreme, but after baptism the soul is free from her.[37][40]

According to Jorunn J. Buckley, a Mandaean baptismal formula was adopted by Valentinian Gnostics in Rome and Alexandria in the 2nd century CE.[41]: 109

Death

[edit]

With baptism was also connected the anointing with oil, and hence we can also understand the death sacrament occurring among some Valentinians consisting in an anointing with a mixture of oil and water.[28] This death sacrament has naturally the express object of assuring the soul the way to the highest heaven "so that the soul may be intangible and invisible to the higher mights and powers".[28] In this connection we also find a few formulae which are entrusted to the faithful, so that their souls may pronounce them on their journey upwards. One of these formulae runs:

I am a son from the Father – the Father who had a pre-existence, and a son in Him who is pre-existent. I have come to behold all things, both those which belong to myself and others, although, strictly speaking, they do not belong to others, but to Achamoth, who is female in nature, and made these things for herself. For I derive being from Him who is pre-existent, and I come again to my own place whence I went forth…[42]

Another formula is appended, in which there is a distinction in the invocation between the higher and lower Sophia. Another prayer of the same style is to be found in Irenaeus i. 13, and it is expressly stated that after prayer is pronounced the Mother throws the Homeric helmet (cf. the Tarnhelm) over the faithful soul, and so makes him invisible to the mights and powers which surround and attack him.[37]

Reaction

[edit]On the other hand, a reaction took place here and there against the sacramental rites. A pure piety, rising above mere sacramentalism, breathes in the words of the Gnostics preserved in Excerpta ex Theodoto, 78, 2:

But not baptism alone sets us free, but knowledge (gnosis): who we were, what we have become, where we were, whither we have sunk, whither we hasten, whence we are redeemed, what is birth and what rebirth.[37]

Relationship with the Church

[edit]The distinction between the human and divine Saviour was a major point of contention between the Valentinians and the Church. Valentinus separated Christ into three figures; the spiritual, the psychical, and the material. Each of the three Christ figures had its own meaning and purpose.[43] They acknowledged that Christ suffered and died, but believed that "in his incarnation, Christ transcended human nature so that he could prevail over death by divine power".[44] These beliefs are what caused Irenaeus to say of the Valentinians, "Certainly they confess with their tongues the one Jesus Christ, but in their minds they divide him."[45] In one passage in the account of Irenaeus, it is directly stated that the redeemer assumed a psychical body to redeem the psychical, for the spiritual already belong by nature to the celestial world and no longer require any historical redemption, while the material is incapable of redemption,[31] as "flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God; neither doth corruption inherit incorruption".[46]

Many Valentinian traditions and practices also clashed with those of the Church. They often met at unauthorized gatherings and rejected ecclesiastical authority, based on their belief that they were all equal. Members of the movement took turns administering sacraments, as well as preaching.[47] Among the Valentinians, women were considered to be equal, or at least nearly equal to men. There were female prophets, teachers, healers, evangelists and even priests, which was very different from the Church's view of women at the time.[48] Valentinians held normal jobs, got married and raised children just like Christians; however they regarded these pursuits as being less important than gnosis, which was to be achieved individually.[49] The beliefs of the Valentinians were much more oriented towards the individual than the group, and salvation was not seen as being universal, as it was in the Church.

The main disagreements between the Valentinians and the Church were in the notions that God and the creator were two separate entities, the idea that the creator was flawed and formed man and Earth out of ignorance and confusion, and the separation of Christ's human form and divine form. Church authorities believed that Valentinian theology was "a wickedly casuistic way of subverting their authority and thereby threatening the ecclesiastical order with anarchy."[47] The practices and rituals of the Valentinians were also different from those of the Christian Church; however they considered themselves to be Christians and not pagans or heretics. By referring to themselves as Christians they worsened their relationship with the Church, who viewed them not only as heretics, but as rivals.[50]

Although the Valentinians publicly professed their faith in one God, "in their own private meetings they insisted on discriminating between the popular image of God – as master, king, lord, creator, and judge – and what that image represented: God understood as the ultimate source of all being."[51] Aside from the Church fathers, however, "the majority of Christians did not recognize the followers of Valentinus as heretics. Most could not tell the difference between Valentinian and orthodox teaching."[51] This was partially because Valentinus used many books that now belong to the Old and New Testaments as a basis for interpretation in his own writing. He based his work on proto-orthodox Christian canon instead of on Gnostic scripture, and his style was similar to that of early Christian works. In this way, Valentinus tried to bridge the gap between Gnostic religion and early Catholicism.[52] By attempting to bridge this gap, however, Valentinus and his followers became the proverbial wolves in sheep's clothing. "The apparent similarity with orthodox teaching only made this heresy more dangerous – like poison disguised as milk."[51] Valentinian Gnosticism was "the most influential and sophisticated form of Gnostic teaching, and by far the most threatening to the church."[51]

Texts

[edit]Valentinian works are named in reference to the bishop and teacher Valentinus. Circa 153 AD, Valentinus developed a complex cosmology outside the Sethian tradition. At one point he was close to being appointed the Bishop of Rome of what is now the Roman Catholic Church. Works attributed to his school are listed below, and fragmentary pieces directly linked to him are noted with an asterisk:

- The Divine Word Present in the Infant (Fragment A) *

- On the Three Natures (Fragment B) *

- Adam's Faculty of Speech (Fragment C) *

- To Agathopous: Jesus' Digestive System (Fragment D) *

- Annihilation of the Realm of Death (Fragment F) *

- On Friends: The Source of Common Wisdom (Fragment G) *

- Epistle on Attachments (Fragment H) *

- Summer Harvest *

- The Gospel of Truth *

- Tripartite Tractate

- Ptolemy's Version of the Gnostic Myth

- Prayer of the Apostle Paul

- Ptolemy's Epistle to Flora

- Treatise on the Resurrection (Epistle to Rheginus)

- Gospel of Philip

- A Valentinian Exposition

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Valentinus". EBSCO Information Services, Inc. Retrieved May 15, 2025.

- ^ Green 1985, 244[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Green 1985, 245[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Lyons, Irenaeus of (2012-03-28). Against Heresies. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4536-2460-9.

- ^ a b "Valentinus – early and medieval christian heresy". University of Oregon WordPress Hosting – Educational blogs from our community. May 31, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2025.

- ^ Marina, Marko (October 18, 2023). "Was Valentinus an Ancient Heretic or a True Christian?". Early Christian Texts. Retrieved May 15, 2025.

- ^ Wilson 1958, 133

- ^ a b Holroyd 1994, 32

- ^ a b Roukema 1998, 129

- ^ Churton 1987, 53

- ^ Filoramo 1990, 166

- ^ Goodrick-Clarke 2002, 182

- ^ Pagels 1979, 37

- ^ Holroyd 1994, 37

- ^ Roukema 1998, 130

- ^ Bousset 1911, pp. 853–854.

- ^ Mead 1903, 396.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bousset 1911, p. 854.

- ^ Irenaeus i. 29

- ^ a b c d e Bousset 1911, p. 853.

- ^ a b Irenaeus i. 29, 30

- ^ Irenaeus i. 29, 3

- ^ a b Bousset 1911, pp. 854–855.

- ^ Horus, according to Francis Legge, generally appeared in Alexandria "with hawk's head and human body dressed in the cuirass and boots of a Roman gendarme or stationarius, which would be appropriate enough for a sentinel or guard." Legge 1914, 105.

- ^ Irenaeus i. 4, 2

- ^ Schwartz, A porien, i. 292

- ^ Dina Ripsman Eylon, Reincarnation in Jewish mysticism and gnosticism, Edwin Mellen Press, 2003

- ^ a b c Irenaeus i. 21, 4

- ^ Irenaeus i. 30

- ^ Irenaeus i. 6, 4

- ^ a b Irenaeus i. 6, 1

- ^ Clemens Stromata ii. 20, 114

- ^ a b c d e f Bousset 1911, p. 855.

- ^ Hippolytus Philosophumena 6, 37

- ^ Clemens iv. 13, 91

- ^ a b c Irenaeus i. 21, 3

- ^ a b c d e f Bousset 1911, p. 856.

- ^ Irenaeus i. 13, 3,6

- ^ a b Excerpta ex Theodoto, 22

- ^ Excerpta ex Theodoto. 77

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2010). Turning the Tables on Jesus: The Mandaean View. In Horsley, Richard (March 2010). Christian Origins. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451416640.(pp94-111). Minneapolis: Fortress Press

- ^ Irenaeus i. 21, 5

- ^ Rudolph 1977, 166

- ^ Pagels 1979, 96

- ^ Rudolph 1977, 155

- ^ 1 Corinthians 15:50

- ^ a b Holroyd 1994, 33

- ^ Pagels 1979, 60

- ^ Pagels 1979, 146

- ^ Rudolph 1977, 206

- ^ a b c d Pagels 1979, 32

- ^ Layton (ed.) 1987, xxii

Bibliography

[edit]- Bermejo, Fernando (1998). La escisión imposible. Lectura del gnosticismo valentiniano. Salamanca: Publicaciones Universidad Pontificia.

- Churton, Tobias (1987). The Gnostics. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson Limited.

- Filoramo, Giovanni (1990). A History of Gnosticism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Limited.

- Green, Henry A. (1985). The Economic and Social Origins of Gnosticism. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

- Harvey, William Wigan (1857). Sancti Irenaei. Vol. I. Typis Academicis.

- Holroyd, Stuart (1994). The Elements of Gnosticism. Dorset: Element Books Limited.

- Layton, Bentley, ed. (1987). The Gnostic Scriptures. New York: Doubleday.

- Legge, Francis (1914). Forerunners and Rivals of Christianity. New York: University Books. p. 105.

- Markschies, Christoph (2020). Valentinianism: new studies. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-41481-5. OCLC 1120784980.

- Mead, G.R.S (1903). Did Jesus Live 100 B.C.?. London: The Theosophical Publishing Society.

- Mead, G.R.S (1906). Thrice Greatest Hermes: Studies in Hellenistic Theosophy and Gnosis. Vol. I. London and Benares: The Theosophical Publishing Society.

- Pagels, Elaine (1979). The Gnostic Gospels. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780394502786.

- Roukema, Riemer (1998). Gnosis and Faith in Early Christianity. Harrisburg: Trinity Press International.

- Rudolph, Kurt (1977). Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism. San Francisco: Harper and Row Publishers.

- Thomassen, Einar (2005). The Spiritual Seed: The Church of the Valentinians. Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies. Brill Academic Publishers.

- Tite, Philip (2009). Valentinian ethics and paraenetic discourse: determining the social function of moral exhortation in Valentinian Christianity. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-2852-7. OCLC 593295838.

- Wilson, Robert McLachlan (1958). The Gnostic Problem. London: A.R. Mowbray & Co. Limited.

- Wilson, Robert McLachlan (1980). "Valentianism and the Gospel of Truth". In Layton, Bentley (ed.). The Rediscovery of Gnosticism. Leiden. pp. 133–45.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bousset, Wilhelm (1911). "Valentinus and the Valentinians". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 852–857. Bousset's article contains a detailed survey of the classical authorities writing on the topic, some of which is replicated here in footnotes.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Valentinus and Valentinians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Valentinus and Valentinians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

[edit]- Bousset, Wilhelm (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). pp. 852–857.

- Valentinus and the Valentinian Tradition – Comprehensive collection of material on Valentinian mythology, theology and tradition (from the Gnosis Archive website).

- Patristic Material on Valentinus – Complete collection of patristic sources mentioning Valentinus.

- Valentinus – A Gnostic for All Seasons Introductory essay by Stephan A. Hoeller (from the Gnosis Archive website).

Valentinianism

View on GrokipediaValentinianism was one of the most widespread and intellectually sophisticated branches of Gnostic Christianity in the second century CE, centered on a mythological framework of divine emanations from an unknowable Father, where the lowest aeon, Sophia, through her misguided desire, precipitated the formation of the flawed material cosmos under a subordinate creator.[1][2] This system, articulated by its founder Valentinus, distinguished three human types—hylic (material), psychic (soul-endowed), and pneumatic (spiritual)—with salvation reserved primarily for the pneumatics via gnosis, an intuitive knowledge awakening the divine spark within to reunite with the pleroma, the realm of fullness.[1][3] Valentinus, born around 100 CE in Phrebonis, Egypt, and educated in Alexandria under teachers linked to apostolic traditions, relocated to Rome circa 136 CE, where he developed and disseminated his teachings, nearly securing the bishopric in 143 CE amid a competitive ecclesiastical environment.[4][2] His followers, including figures like Ptolemy and Heracleon, elaborated the doctrine into varied subsystems, integrating it with mainstream Christian practices such as baptism and ethical norms derived from the Sermon on the Mount, while viewing sin as ignorance rather than willful transgression.[1][3] Though preserved largely through critical accounts by opponents like Irenaeus—whose reconstructions, while polemical, align substantially with primary texts recovered from Nag Hammadi—Valentinianism exerted enduring influence across the Roman Empire, from Gaul to Mesopotamia, persisting into the fifth century and shaping esoteric interpretations of scripture and cosmology.[2][3] Its emphasis on allegorical myth over literalism and accommodation of diverse believers highlighted early Christianity's pluralism, even as emerging orthodoxy marginalized it as heresy, suppressing texts until modern discoveries confirmed its depth and adaptability.[1][2]