Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hallucination

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

| Hallucination | |

|---|---|

| |

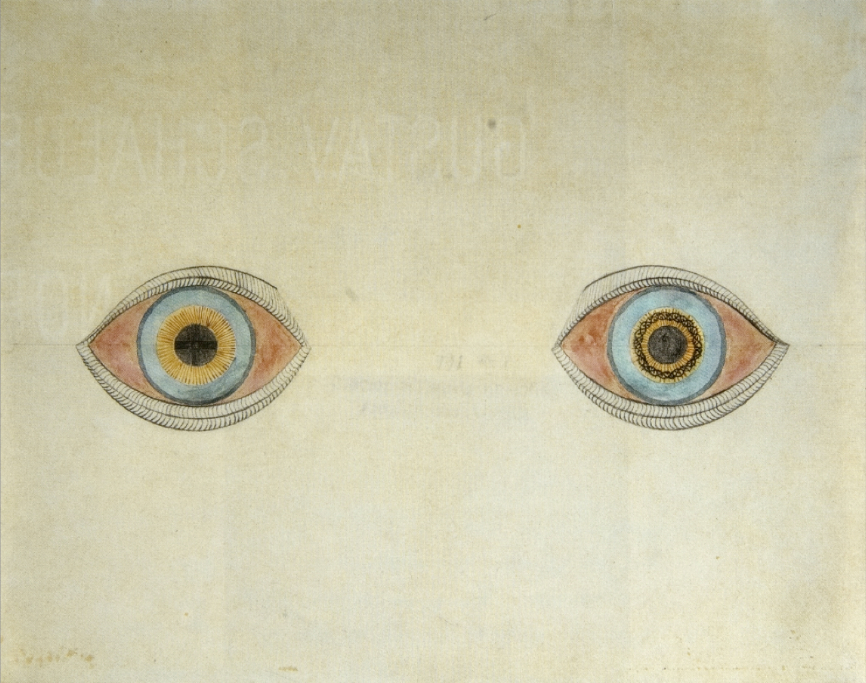

| My eyes at the moment of the apparitions by August Natterer, a German artist who created many drawings of his hallucinations | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Causes | Hypnagogia, Peduncular hallucinosis, Delirium tremens, Parkinson's disease, Delusion, Lewy body dementia, Charles Bonnet syndrome, hallucinogens, sensory deprivation, schizophrenia, psychedelics, sleep paralysis, drug intoxication or withdrawal, sleep deprivation, epilepsy, psychological stress, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, fever,[1] covert weaponry[2][3] |

| Treatment | Cognitive behavioral therapy[4] and metacognitive training[5] |

| Medication | Antipsychotic, AAP |

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external context stimulus that has the compelling sense of reality.[6] They are distinguishable from several related phenomena, such as dreaming (REM sleep), which does not involve wakefulness; pseudohallucination, which does not mimic real perception, and is accurately perceived as unreal; illusion, which involves distorted or misinterpreted real perception; and mental imagery, which does not mimic real perception, and is under voluntary control.[7] Hallucinations also differ from "delusional perceptions", in which a correctly sensed and interpreted stimulus (i.e., a real perception) is given some additional significance.[8]

Hallucinations can occur in any sensory modality—visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, proprioceptive, equilibrioceptive, nociceptive, thermoceptive and chronoceptive. Hallucinations are referred to as multimodal if multiple sensory modalities occur.[9][10]

A mild form of hallucination is known as a disturbance, and can occur in most of the senses above. These may be things like seeing movement in peripheral vision, or hearing faint noises or voices. Auditory hallucinations are very common in schizophrenia. They may be benevolent (telling the subject good things about themselves) or malicious (cursing the subject). 55% of auditory hallucinations are malicious in content,[11] for example, people talking about the subject, not speaking to them directly. Like auditory hallucinations, the source of the visual counterpart can also be behind the subject. This can produce a feeling of being looked or stared at, usually with malicious intent.[12][13] Frequently, auditory hallucinations and their visual counterpart are experienced by the subject together.[14]

Hypnagogic hallucinations and hypnopompic hallucinations are considered normal phenomena. Hypnagogic hallucinations can occur as one is falling asleep and hypnopompic hallucinations occur when one is waking up. Hallucinations can be associated with drug use (particularly deliriants), sleep deprivation, psychosis (including stress-related psychosis[15]), neurological disorders, and delirium tremens. Many hallucinations happen also during sleep paralysis.[16]

The word "hallucination" itself was introduced into the English language by the 17th-century physician Sir Thomas Browne in 1646 from the derivation of the Latin word alucinari meaning to wander in the mind. For Browne, hallucination means a sort of vision that is "depraved and receive[s] its objects erroneously".[17]

Classification

[edit]Hallucinations may be manifested in a variety of forms.[18] Various forms of hallucinations affect different senses, sometimes occurring simultaneously, creating multiple sensory hallucinations for those experiencing them.[9]

Auditory

[edit]Auditory hallucinations (also known as paracusia)[19] are the perception of sound without outside stimulus. Auditory hallucinations can be divided into elementary and complex, along with verbal and nonverbal. These hallucinations are the most common type of hallucination, with auditory verbal hallucinations being more common than nonverbal.[20][21] Elementary hallucinations are the perception of sounds such as hissing, whistling, an extended tone, and more.[22] In many cases, tinnitus is an elementary auditory hallucination.[21] However, some people who experience certain types of tinnitus, especially pulsatile tinnitus, are actually hearing the blood rushing through vessels near the ear. Because the auditory stimulus is present in this situation, it does not qualify it as a hallucination.[23]

Complex hallucinations are those of voices, music,[21] or other sounds that may or may not be clear, may or may not be familiar, and may be friendly, aggressive, or among other possibilities. A hallucination of a single individual person of one or more talking voices is particularly associated with psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, and hold special significance in diagnosing these conditions.[24]

In schizophrenia, voices are normally perceived coming from outside the person, but in dissociative disorders they are perceived as originating from within the person, commenting in their head instead of behind their back. Differential diagnosis between schizophrenia and dissociative disorders is challenging due to many overlapping symptoms, especially Schneiderian first rank symptoms such as hallucinations.[25] However, many people who do not have a diagnosable mental illness may sometimes hear voices as well.[26] One important example to consider when forming a differential diagnosis for a patient with paracusia is lateral temporal lobe epilepsy. Despite the tendency to associate hearing voices, or otherwise hallucinating, and psychosis with schizophrenia or other psychiatric illnesses, it is crucial to take into consideration that, even if a person does exhibit psychotic features, they do not necessarily have a psychiatric disorder on its own. Disorders such as Wilson's disease, various endocrine diseases, numerous metabolic disturbances, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, porphyria, sarcoidosis, and many others can present with psychosis.[27]

Musical hallucinations are also relatively common in terms of complex auditory hallucinations and may be the result of a wide range of causes ranging from hearing-loss (such as in musical ear syndrome, the auditory version of Charles Bonnet syndrome), lateral temporal lobe epilepsy,[28] arteriovenous malformation,[29] stroke, lesion, abscess, or tumor.[30]

The Hearing Voices Movement is a support and advocacy group for people who hallucinate voices, but do not otherwise show signs of mental illness or impairment.[31]

High caffeine consumption has been linked to an increase in likelihood of one experiencing auditory hallucinations.[32] A study conducted by the La Trobe University School of Psychological Sciences revealed that as few as five cups of coffee a day (approximately 500 mg of caffeine) could trigger the phenomenon.[33]

Visual

[edit]A visual hallucination is "the perception of an external visual stimulus where none exists".[34] A separate but related phenomenon is a visual illusion, which is a distortion of a real external stimulus. Visual hallucinations are classified as simple or complex:

- Simple visual hallucinations (SVH) are also referred to as non-formed visual hallucinations and elementary visual hallucinations. These terms refer to lights, colors, geometric shapes, and indiscrete objects. These can be further subdivided into phosphenes which are SVH without structure, and photopsias which are SVH with geometric structures.

- Complex visual hallucinations (CVH) are also referred to as formed visual hallucinations. CVHs are clear, lifelike images or scenes such as people, animals, objects, places, etc.

For example, one may report hallucinating a giraffe. A simple visual hallucination is an amorphous figure that may have a similar shape or color to a giraffe (looks like a giraffe), while a complex visual hallucination is a discrete, lifelike image that is, unmistakably, a giraffe.

Command

[edit]Command hallucinations are hallucinations in the form of commands; they appear to be from an external source, or can appear coming from the subject's head.[35] The contents of the hallucinations can range from the innocuous to commands to cause harm to the self or others.[35] Command hallucinations are often associated with schizophrenia. People experiencing command hallucinations may or may not comply with the hallucinated commands, depending on the circumstances. Compliance is more common for non-violent commands.[36]

Command hallucinations are sometimes used to defend a crime that has been committed, often homicides.[37] In essence, it is a voice that one hears and it tells the listener what to do. Sometimes the commands are quite benign directives such as "Stand up" or "Shut the door."[38] Whether it is a command for something simple or something that is a threat, it is still considered a "command hallucination." Some helpful questions that can assist one in determining if they may have this includes: "What are the voices telling you to do?", "When did your voices first start telling you to do things?", "Do you recognize the person who is telling you to harm yourself (or others)?", "Do you think you can resist doing what the voices are telling you to do?"[38]

Olfactory

[edit]Phantosmia (olfactory hallucinations), smelling an odor that is not actually there,[39] and parosmia (olfactory illusions), inhaling a real odor but perceiving it as different scent than remembered,[40] are distortions to the sense of smell (olfactory system), and in most cases, are not caused by anything serious and will usually go away on their own in time.[39] It can result from a range of conditions such as nasal infections, nasal polyps, dental problems, migraines, head injuries, seizures, strokes, or brain tumors.[39][41] Environmental exposures can sometimes cause it as well, such as smoking, exposure to certain types of chemicals (e.g., insecticides or solvents), or radiation treatment for head or neck cancer.[39] It can also be a symptom of certain mental disorders such as depression, bipolar disorder, intoxication, substance withdrawal, or psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia).[41] The perceived odors are usually unpleasant and commonly described as smelling burned, foul, spoiled, or rotten.[39]

Tactile

[edit]Tactile hallucinations are the illusion of tactile sensory input, simulating various types of pressure to the skin or other organs. One subtype of tactile hallucination, formication, is the sensation of insects crawling underneath the skin and is frequently associated with prolonged cocaine use.[42] However, formication may also be the result of normal hormonal changes such as menopause, or disorders such as peripheral neuropathy, high fevers, Lyme disease, skin cancer, and more.[42]

Gustatory

[edit]This type of hallucination is the perception of taste without a stimulus. These hallucinations, which are typically strange or unpleasant, are relatively common among individuals who have certain types of focal epilepsy, especially temporal lobe epilepsy. The regions of the brain responsible for gustatory hallucination in this case are the insula and the superior bank of the sylvian fissure.[43][44]

Sexual

[edit]Sexual hallucinations are the perception of erogenous or orgasmic stimuli. They may be unimodal or multimodal in nature and frequently involve sensation in the genital region, though it is not exclusive.[45] Frequent examples of sexual hallucinations include the sensation of being penetrated, experiencing orgasm, feeling as if one is being touched in an erogenous zone, sensing stimulation in the genitals, feeling the fondling of one's breasts or buttocks and tastes or smells related to sexual activity.[46] Visualizations of sexual content and auditory voices making sexually explicit remarks may sometimes be included in this classification. While it features components of other classifications, sexual hallucinations are distinct due to the orgasmic component and unique presentation.[47]

The regions of the brain responsible differ by the subsection of sexual hallucination. In orgasmic auras, the mesial temporal lobe, right amygdala and hippocampus are involved.[48][49] In males, genital specific sensations are related to the postcentral gyrus and arousal and ejaculation are linked to stimulation in the posterior frontal lobe.[50][51] In females, however, the hippocampus and amygdala are connected.[51][52] Limited studies have been done to understand the mechanism of action behind sexual hallucinations in epilepsy, substance use, and post-traumatic stress disorder etiologies.[47]

Somatic

[edit]Somatic hallucinations refer to an interoceptive sensory experience in the absence of stimulus. Somatic hallucinations can be broken down into further subcategories: general, algesic, kinesthetic, and cenesthopathic.[45][47]

- Cenesthopathic- Effecting the cenesthetic sensory modality, cenesthopathic hallucinations are a pathological alteration in the sense of bodily existence, caused by aberrant bodily sensations. Most often, cenesthopathic hallucinations will refer to sensation in the visceral organs. Therefore, it is also known as visceral hallucinations.[53][47] Manifestations are often subjective, hard to describe and unique to the sufferer. Common manifestations include pressure, burning, tickling, or tightening in various body systems.[54] While these hallucinations can be experienced by a variety of psychiatric and neurological disorder, cenesthopathic schizophrenia is recognized by the ICD as a subtype of schizophrenia marked by primarily cenesthopathic hallucinations and other body image aberrations.[55][47]

- Kinesthetic- Kinesthetic hallucinations, effecting the sensory modality of the same name, are the sensation of movement of the limbs or other body parts without actual movement.[56][47][54][53]

- Algesic- Algesic hallucinations, effecting the algesic sensory modality, refers to a perceived perception of pain.[47][54][53]

- General- General somatic hallucination refers to somatic hallucinations not otherwise categorized by the above subsections. Common examples include when an individual feels that their body is being mutilated, i.e. twisted, torn, or disemboweled. Other reported cases are invasion by animals in the person's internal organs, such as snakes in the stomach or frogs in the rectum. The general feeling that one's flesh is decomposing is also classified under this type of this hallucination.[47]

Multimodal

[edit]A hallucination involving sensory modalities is called multimodal, analogous to unimodal hallucinations which have only one sensory modality. The multiple sensory modalities can occur at the same time (simultaneously) or with a delay (serial), be related or unrelated to each other, and be consistent with reality (congruent) or not (incongruent).[9][10] For example, a person talking in a hallucination would be congruent with reality, but a cat talking would not be.

Multimodal hallucinations are correlated to poorer mental health outcomes, and are often experienced as feeling more real.[9]

Cause

[edit]Hallucinations can be caused by a number of factors.[3]

Hypnagogic hallucination

[edit]These hallucinations occur just before falling asleep and affect a high proportion of the population: in one survey 37% of the respondents experienced them twice a week.[57] The hallucinations can last from seconds to minutes; all the while, the subject usually remains aware of the true nature of the images. These may be associated with narcolepsy. Hypnagogic hallucinations are sometimes associated with brainstem abnormalities, but this is rare.[58]

Peduncular hallucinosis

[edit]Peduncular means pertaining to the peduncle, which is a neural tract running to and from the pons on the brain stem. These hallucinations usually occur in the evenings, but not during drowsiness, as in the case of hypnagogic hallucination. The subject is usually fully conscious and then can interact with the hallucinatory characters for extended periods of time. As in the case of hypnagogic hallucinations, insight into the nature of the images remains intact. The false images can occur in any part of the visual field, and are rarely polymodal.[58]

Delirium tremens

[edit]One of the more enigmatic forms of visual hallucination is the highly variable, possibly polymodal delirium tremens. It is associated with withdrawal in alcohol use disorder. Individuals with delirium tremens may be agitated and confused, especially in the later stages of this disease.[59] Insight is gradually reduced with the progression of this disorder. Sleep is disturbed and occurs for a shorter period of time, with rapid eye movement sleep.[60]

Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia

[edit]Parkinson's disease is linked with Lewy body dementia for their similar hallucinatory symptoms. Presence hallucinations can be an early indicator of cognitive decline in Parkinson's Disease.[61] The symptoms strike during the evening in any part of the visual field, and are rarely polymodal. The segue into hallucination may begin with illusions[62] where sensory perception is greatly distorted, but no novel sensory information is present. These typically last for several minutes, during which time the subject may be either conscious and normal or drowsy/inaccessible. Insight into these hallucinations is usually preserved and REM sleep is usually reduced. Parkinson's disease is usually associated with a degraded substantia nigra pars compacta, but recent evidence suggests that PD affects a number of sites in the brain. Some places of noted degradation include the median raphe nuclei, the noradrenergic parts of the locus coeruleus, and the cholinergic neurons in the parabrachial area and pedunculopontine nuclei of the tegmentum.[58]

Migraine coma

[edit]This type of hallucination is usually experienced during the recovery from a comatose state. The migraine coma can last for up to two days, and a state of depression is sometimes comorbid. The hallucinations occur during states of full consciousness, and insight into the hallucinatory nature of the images is preserved. It has been noted that ataxic lesions accompany the migraine coma.[58]

Migraine attacks

[edit]Migraine attacks may result in visual hallucinations including auras and in rarer cases, auditory hallucinations.[63]

Charles Bonnet syndrome

[edit]Charles Bonnet syndrome is the name given to visual hallucinations experienced by a partially or severely sight impaired person. The hallucinations can occur at any time and can distress people of any age, as they may not initially be aware that they are hallucinating. They may fear for their own mental health initially, which may delay them sharing with carers until they start to understand it themselves. The hallucinations can frighten and disconcert as to what is real and what is not. The hallucinations can sometimes be dispersed by eye movements, or by reasoned logic such as, "I can see fire but there is no smoke and there is no heat from it" or perhaps, "We have an infestation of rats but they have pink ribbons with a bell tied on their necks." Over elapsed months and years, the hallucinations may become more or less frequent with changes in ability to see. The length of time that the sight impaired person can have these hallucinations varies according to the underlying speed of eye deterioration. A differential diagnosis are ophthalmopathic hallucinations.[64]

Focal epilepsy

[edit]Visual hallucinations due to focal seizures differ depending on the region of the brain where the seizure occurs. For example, visual hallucinations during occipital lobe seizures are typically visions of brightly colored, geometric shapes that may move across the visual field, multiply, or form concentric rings and generally persist from a few seconds to a few minutes. They are usually unilateral and localized to one part of the visual field on the contralateral side of the seizure focus, typically the temporal field. However, unilateral visions moving horizontally across the visual field begin on the contralateral side and move toward the ipsilateral side.[43][65]

Temporal lobe seizures, on the other hand, can produce complex visual hallucinations of people, scenes, animals, and more as well as distortions of visual perception. Complex hallucinations may appear to be real or unreal, may or may not be distorted with respect to size, and may seem disturbing or affable, among other variables. One rare but notable type of hallucination is heautoscopy, a hallucination of a mirror image of one's self. These "other selves" may be perfectly still or performing complex tasks, may be an image of a younger self or the present self, and tend to be briefly present. Complex hallucinations are a relatively uncommon finding in temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Rarely, they may occur during occipital focal seizures or in parietal lobe seizures.[43]

Distortions in visual perception during a temporal lobe seizure may include size distortion (micropsia or macropsia), distorted perception of movement (where moving objects may appear to be moving very slowly or to be perfectly still), a sense that surfaces such as ceilings and even entire horizons are moving farther away in a fashion similar to the dolly zoom effect, and other illusions.[66] Even when consciousness is impaired, insight into the hallucination or illusion is typically preserved.[67]

Drug-induced hallucination

[edit]Drug-induced hallucinations are caused by hallucinogens, dissociatives, and deliriants, including many drugs with anticholinergic actions and certain stimulants, which are known to cause visual and auditory hallucinations. Some psychedelics such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin can cause hallucinations that range in the spectrum of mild to intense.[citation needed]

Hallucinations, pseudohallucinations, or intensification of pareidolia, particularly auditory, are known side effects of opioids to different degrees—it may be associated with the absolute degree of agonism or antagonism of especially the kappa opioid receptor, sigma receptors, delta opioid receptor and the NMDA receptors or the overall receptor activation profile as synthetic opioids like those of the pentazocine, levorphanol, fentanyl, pethidine, methadone and some other families are more associated with this side effect than natural opioids like morphine and codeine and semi-synthetics like hydromorphone, amongst which there also appears to be a stronger correlation with the relative analgesic strength. Three opioids, Cyclazocine (a benzormorphan opioid/pentazocine relative) and two levorphanol-related morphinan opioids, Cyclorphan and Dextrorphan are classified as hallucinogens, and Dextromethorphan as a dissociative.[68][69][70] These drugs also can induce sleep (relating to hypnagogic hallucinations) and especially the pethidines have atropine-like anticholinergic activity, which was possibly also a limiting factor in the use, the psychotomimetic side effects of potentiating morphine, oxycodone, and other opioids with scopolamine (respectively in the Twilight Sleep technique and the combination drug Skophedal, which was eukodal (oxycodone), scopolamine and ephedrine, called the "wonder drug of the 1930s" after its invention in Germany in 1928, but only rarely specially compounded today) (q.q.v.).[71]

Sensory deprivation hallucination

[edit]Hallucinations can be caused by sensory deprivation when it occurs for prolonged periods of time, and almost always occurs in the modality being deprived (visual for blindfolded/darkness, auditory for muffled conditions, etc.)[72]

Experimentally-induced hallucinations

[edit]Anomalous experiences, such as so-called benign hallucinations, may occur in a person in a state of good mental and physical health, even in the apparent absence of a transient trigger factor such as fatigue, intoxication or sensory deprivation.

The evidence for this statement has been accumulating for more than a century. Studies of benign hallucinatory experiences go back to 1886 and the early work of the Society for Psychical Research,[73][74] which suggested approximately 10% of the population had experienced at least one hallucinatory episode in the course of their life. More recent studies have validated these findings; the precise incidence found varies with the nature of the episode and the criteria of "hallucination" adopted, but the basic finding is now well-supported.[75]

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity

[edit]There is tentative evidence of a relationship with non-celiac gluten sensitivity, the so-called "gluten psychosis".[76]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Dopaminergic and serotonergic hallucinations

[edit]It has been reported that in serotonergic hallucinations, the person maintains an awareness that they are hallucinating, unlike dopaminergic hallucinations.[16]

Neuroanatomy

[edit]Hallucinations are associated with structural and functional abnormalities in primary and secondary sensory cortices. Reduced grey matter in regions of the superior temporal gyrus/middle temporal gyrus, including Broca's area, is associated with auditory hallucinations as a trait, while acute hallucinations are associated with increased activity in the same regions along with the hippocampus, parahippocampus, and the right hemispheric homologue of Broca's area in the inferior frontal gyrus.[77] Grey and white matter abnormalities in visual regions are associated with hallucinations in diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, further supporting the notion of dysfunction in sensory regions underlying hallucinations.[78]

One proposed model of hallucinations posits that over-activity in sensory regions, which is normally attributed to internal sources via feedforward networks to the inferior frontal gyrus, is interpreted as originating externally due to abnormal connectivity or functionality of the feedforward network.[77] This is supported by cognitive studies of those with hallucinations, who have demonstrated abnormal attribution of self generated stimuli.[79]

Disruptions in thalamocortical circuitry may underlie the observed top down and bottom up dysfunction.[80] Thalamocortical circuits, composed of projections between thalamic and cortical neurons and adjacent interneurons, underlie certain electrophysical characteristics (gamma oscillations) that are associated with sensory processing. Cortical inputs to thalamic neurons enable attentional modulation of sensory neurons. Dysfunction in sensory afferents, and abnormal cortical input may result in pre-existing expectations modulating sensory experience, potentially resulting in the generation of hallucinations. Hallucinations are associated with less accurate sensory processing, and more intense stimuli with less interference are necessary for accurate processing and the appearance of gamma oscillations (called "gamma synchrony"). Hallucinations are also associated with the absence of reduction in P50 amplitude in response to the presentation of a second stimuli after an initial stimulus; this is thought to represent failure to gate sensory stimuli, and can be exacerbated by dopamine release agents.[81]

Abnormal assignment of salience to stimuli may be one mechanism of hallucinations. Dysfunctional dopamine signaling may lead to abnormal top down regulation of sensory processing, allowing expectations to distort sensory input.[82]

Treatments

[edit]There are few treatments for many types of hallucinations. However, for those hallucinations caused by mental disease, a psychologist or psychiatrist should be consulted, and treatment will be based on the observations of those doctors. Antipsychotic and atypical antipsychotic medication may also be utilized to treat the illness if the symptoms are severe and cause significant distress.[83] For other causes of hallucinations there is no factual evidence to support any one treatment is scientifically tested and proven. However, abstaining from hallucinogenic drugs, stimulant drugs, managing stress levels, living healthily, and getting plenty of sleep can help reduce the prevalence of hallucinations. In all cases of hallucinations, medical attention should be sought out and informed of one's specific symptoms. Meta-analyses show that cognitive behavioral therapy[4] and metacognitive training[5] can also reduce the severity of hallucinations. Furthermore, there are recovery movements all around the world that advocate for individuals with schizophrenia or voice-hearers (individuals that hear voices). The Hearing Voices Movement,[84][circular reference] starting in Europe, aims to[neutrality is disputed] utilize knowledge and experience of voice hearers combined with experts in disorders such as schizophrenia, such as psychiatrists.

Epidemiology

[edit]Prevalence of hallucinations varies depending on underlying medical conditions,[85][9] which sensory modalities are affected,[10] age[86][85] and culture.[87] As of 2022,[update] auditory hallucinations are the most well studied and most common sensory modality of hallucinations, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 9.6%.[86] Children and adolescents have been found to experience similar rates (12.7% and 12.4% respectively) which occur mostly during late childhood and adolescence. In this group, hallucinations are not necessarily indicative of later psychopathology and are recognized to occur on a continuum which includes normal, transient hallucinatory phenomena.[88] However, hallucinations become increasingly associated with psychopathology in late adolescence.[88]

The prevalence of hallucinations in adults and those over 60 is comparatively lower (with rates of 5.8% and 4.8% respectively).[86][85] For those with schizophrenia, the lifetime prevalence of hallucinations is 80%[9] and the estimated prevalence of visual hallucinations is 27%, compared to 79% for auditory hallucinations.[9] A 2019 study suggested 16.2% of adults with hearing impairment experience hallucinations, with prevalence rising to 24% in the most hearing impaired group.[89]

A risk factor for multimodal hallucinations is prior experience of unimodal hallucinations.[9] In 90% cases of psychosis, a visual hallucination occurs in combination with another sensory modality, most often being auditory or somatic.[9] In schizophrenia, multimodal hallucinations are twice as common as unimodal ones.[9]

A 2015 review of 55 publications from 1962 to 2014 found 16–28.6% of those experiencing hallucinations report at least some religious content in them,[90]: 415 along with 20–60% reporting some religious content in delusions.[90]: 415 There is some evidence for delusions being a risk factor for religious hallucinations, with and 61.7% of people having experienced any delusion and 75.9% of those having experienced a religious delusion found to also experience hallucinations.[90]: 421

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Adamis D, Treloar A, Martin FC, Macdonald AJ (December 2007). "A brief review of the history of delirium as a mental disorder". History of Psychiatry. 18 (72 Pt 4): 459–69. doi:10.1177/0957154X07076467. hdl:2262/51619. PMID 18590023. S2CID 24424207.

- ^ Burke M (4 February 2019). "Russian Navy has new weapon that makes targets hallucinate, vomit: Report". The Hill.

- ^ a b Patterson C, Procter N (2023-05-24). "Hallucinations in the movies tend to be about chaos, violence and mental distress. But they can be positive too". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2023-05-28. Retrieved 2023-05-28.

- ^ a b Turner DT, Burger S, Smit F, Valmaggia LR, van der Gaag M (March 2020). "What Constitutes Sufficient Evidence for Case Formulation-Driven CBT for Psychosis? Cumulative Meta-analysis of the Effect on Hallucinations and Delusions". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (5): 1072–1085. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa045. PMC 7505201. PMID 32221536.

- ^ a b Penney D, Sauvé G, Mendelson D, Thibaudeau É, Moritz S, Lepage M (March 2022). "Immediate and Sustained Outcomes and Moderators Associated With Metacognitive Training for Psychosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry. 79 (5): 417–429. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0277. PMC 8943641. PMID 35320347.

- ^ El-Mallakh RS, Walker KL (2010). "Hallucinations, Psuedohallucinations, and Parahallucinations". Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 73 (1): 34–42. doi:10.1521/psyc.2010.73.1.34. PMID 20235616. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ Chiu LP (1989). "Differential diagnosis and management of hallucinations" (PDF). Journal of the Hong Kong Medical Association. t 41 (3): 292–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- ^ Adámek P, Langová V, Horáček J (2022-03-21). "Early-stage visual perception impairment in schizophrenia, bottom-up and back again". Schizophrenia. 8 (1): 27. doi:10.1038/s41537-022-00237-9. ISSN 2754-6993. PMC 8938488. PMID 35314712.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Montagnese M, Leptourgos P, Fernyhough C, Waters F, Larøi F, Jardri R, et al. (January 2021). "A Review of Multimodal Hallucinations: Categorization, Assessment, Theoretical Perspectives, and Clinical Recommendations". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 47 (1): 237–248. doi:10.31219/osf.io/zebxv. PMC 7825001. PMID 32772114. S2CID 243338891.

- ^ a b c Dudley R, Aynsworth C, Cheetham R, McCarthy-Jones S, Collerton D (November 2018). "Prevalence and characteristics of multi-modal hallucinations in people with psychosis who experience visual hallucinations". Psychiatry Research. 269: 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.032. PMID 30145297. S2CID 52092886.

- ^ Waters F (30 December 2014). "Auditory Hallucinations in Adult Populations". Psychiatric Times. Vol 31 No 12. 31 (12). Archived from the original on 2022-06-07. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- ^ "The Sense of Being Stared At -- Part 1: Is it Real or Illusory?".

- ^ "Auditory Hallucinations". clevelandclinic.org.

- ^ Waters F, Collerton D, Ffytche DH, Jardri R, Pins D, Dudley R, et al. (July 2014). "Visual hallucinations in the psychosis spectrum and comparative information from neurodegenerative disorders and eye disease". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 40 (4): S233 – S245. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu036. PMC 4141306. PMID 24936084.

- ^ Prateek Varshney, Santosh Kumar Chaturvedi: Stress related and stress induced psychosis

- ^ a b Jalal B (November 2018). "The neuropharmacology of sleep paralysis hallucinations: serotonin 2A activation and a novel therapeutic drug". Psychopharmacology. 235 (11): 3083–3091. doi:10.1007/s00213-018-5042-1. PMC 6208952. PMID 30288594.

- ^ Browne T (1646). "XVIII: That Moles are blinde and have no eyes". Pseudodoxia Epidemica. Vol. III.

- ^ Chen E, Berrios GE (1996). "Recognition of hallucinations: a new multidimensional model and methodology". Psychopathology. 29 (1): 54–63. doi:10.1159/000284972. PMID 8711076.

- ^ "Paracusia". thefreedictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S (2014). Abnormal Psychology (6e ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 283.

- ^ a b c "Auditory Hallucinations: Causes, Symptoms, Types & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 2024-01-01. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

- ^ "Mental State Examination 3 – Perception and Mood – Pathologia". Archived from the original on 2024-01-01. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

- ^ Tracy D, Shergill S (2013-04-26). "Mechanisms Underlying Auditory Hallucinations—Understanding Perception without Stimulus". Brain Sciences. 3 (2): 642–669. doi:10.3390/brainsci3020642. ISSN 2076-3425. PMC 4061847. PMID 24961419.

- ^ Chaudhury S (2010). "Hallucinations: Clinical aspects and management". Industrial Psychiatry Journal. 19 (1): 5–12. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.77625. ISSN 0972-6748. PMC 3105559. PMID 21694785.

- ^ Shibayama M (2011). "[Differential diagnosis between dissociative disorders and schizophrenia]". Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi = Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica. 113 (9): 906–911. PMID 22117396.

- ^ Thompson A (September 15, 2006). "Hearing Voices: Some People Like It". LiveScience.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ^ Endres D, Matysik M, Feige B, Venhoff N, Schweizer T, Michel M, et al. (2020-09-14). "Diagnosing Organic Causes of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: Findings from a One-Year Cohort of the Freiburg Diagnostic Protocol in Psychosis (FDPP)". Diagnostics. 10 (9): 691. doi:10.3390/diagnostics10090691. ISSN 2075-4418. PMC 7555162. PMID 32937787.

- ^ Engmann B, Reuter M (2009). "Melodiewahrnehmung ohne äußeren Reiz: Halluzination oder Epilepsie? Ein Fallbericht" [Spontaneous perception of melodies: Hallucination or epilepsy?]. Nervenheilkunde (in German). 28 (4): 217–221. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1628605.

- ^ Ozsarac M, Aksay E, Kiyan S, Unek O, Gulec FF (July 2012). "De novo cerebral arteriovenous malformation: Pink Floyd's song "Brick in the Wall" as a warning sign". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 43 (1): e17 – e20. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.05.035. PMID 19682829.

- ^ "Rare Hallucinations Make Music In The Mind". ScienceDaily.com. August 9, 2000. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ^ Schaefer B, Boumans J, van Os J, van Weeghel J (2021-04-21). "Emerging Processes Within Peer-Support Hearing Voices Groups: A Qualitative Study in the Dutch Context". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12 647969. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.647969. PMC 8098806. PMID 33967856.

- ^ Fiegl A. "Caffeine Linked to Hallucinations". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 2024-01-01. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

- ^ "Too Much Coffee Can Make You Hear Things That Are Not There". Medical News Today. 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-03-11.

- ^ Pelak V. "Approach to the patient with visual hallucinations". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ^ a b Beck-Sander A, Birchwood M, Chadwick P (February 1997). "Acting on command hallucinations: a cognitive approach". The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 36 (1): 139–148. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01237.x. PMID 9051285.

- ^ Lee TM, Chong SA, Chan YH, Sathyadevan G (December 2004). "Command hallucinations among Asian patients with schizophrenia". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 49 (12): 838–842. doi:10.1177/070674370404901207. PMID 15679207.

- ^ Knoll JL, Resnick PJ (February 2008). "Insanity Defense Evaluations: Toward a Model for Evidence-Based Practice". Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 8 (1): 92–110. doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhm024.

- ^ a b Shea SC. "Uncovering Command Hallucinations". raining Institute for Suicide Assessment. Archived from the original on 2014-01-02.

- ^ a b c d e HealthUnlocked (2014), "Phantosmia (Smelling Odours That Aren't There)", NHS Choices, archived from the original on 2 August 2016, retrieved 6 August 2016

- ^ Hong SC, Holbrook EH, Leopold DA, Hummel T (June 2012). "Distorted olfactory perception: a systematic review". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 132 (S1): S27 – S31. doi:10.3109/00016489.2012.659759. PMID 22582778. S2CID 207416134.

- ^ a b Leopold D (September 2002). "Distortion of olfactory perception: diagnosis and treatment". Chemical Senses. 27 (7): 611–615. doi:10.1093/chemse/27.7.611. PMID 12200340.

- ^ a b Berrios GE (April 1982). "Tactile hallucinations: conceptual and historical aspects". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 45 (4): 285–293. doi:10.1136/jnnp.45.4.285. PMC 491362. PMID 7042917.

- ^ a b c Panayiotopoulos CP (2010). A Clinical Guide to Epileptic Syndromes and their Treatment. doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-644-5. ISBN 978-1-84628-643-8.[page needed]

- ^ Barker P (1997). Assessment in psychiatric and mental health nursing: in search of the whole person. Cheltenham, UK: Stanley Thornes Publishers. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-7487-3174-9.

- ^ a b Blom JD, Mangoenkarso E (9 May 2018). "Sexual Hallucinations in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders and Their Relation With Childhood Trauma". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 9: 193. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00193. PMC 5954108. PMID 29867612.

- ^ Akhtar S, Thomson JA (April 1980). "Schizophrenia and sexuality: a review and a report of twelve unusual cases--part I". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 41 (4): 134–142. PMID 7364736.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Blom JD (2024). "The Diagnostic Spectrum of Sexual Hallucinations". Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 32 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000388. hdl:1887/3730958. PMC 11449261. PMID 38181099.

- ^ Penfield W, Rasmussen T. The cerebral cortex of man: a clinical study of localization of function. London: Macmillan, 1950.[page needed]

- ^ Janszky J, Ebner A, Szupera Z, Schulz R, Hollo A, Szücs A, et al. (September 2004). "Orgasmic aura—a report of seven cases". Seizure. 13 (6): 441–444. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2003.09.005. PMID 15276150.

- ^ Sem-Jacobsen CW. Depth-electrographic stimulation of the human brain and behavior. Toronto: Ryerson, 1968.[page needed]

- ^ a b Surbeck W, Bouthillier A, Nguyen DK (2013). "Bilateral cortical representation of orgasmic ecstasy localized by depth electrodes". Epilepsy & Behavior Case Reports. 1: 62–65. doi:10.1016/j.ebcr.2013.03.002. PMC 4150648. PMID 25667829.

- ^ Chaton L, Chochoi M, Reyns N, Lopes R, Derambure P, Szurhaj W (December 2018). "Localization of an epileptic orgasmic feeling to the right amygdala, using intracranial electrodes". Cortex. 109: 347–351. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2018.07.013. PMID 30126613.

- ^ a b c Lim A, Hoek HW, Deen ML, Blom JD, Bruggeman R, Cahn W, et al. (October 2016). "Prevalence and classification of hallucinations in multiple sensory modalities in schizophrenia spectrum disorders". Schizophrenia Research. 176 (2–3): 493–499. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.010. PMID 27349814.

- ^ a b c Bilder RM (August 2013). "The Neuroscience of Hallucinations". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 28 (5): 511–512. doi:10.1093/arclin/act029.

- ^ Jenkins G, Röhricht F (2007). "From Cenesthesias to Cenesthopathic Schizophrenia: A Historical and Phenomenological Review". Psychopathology. 40 (5): 361–368. doi:10.1159/000106314. PMID 17657136.

- ^ Moreno FC, Barea MV (April 2021). "A first psychotic episode with kinesthetic hallucinations. Report of a case". European Psychiatry. 64 (S1): S795. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2101. PMC 9479843.

- ^ Ohayon MM, Priest RG, Caulet M, Guilleminault C (October 1996). "Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations: pathological phenomena?". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (4): 459–467. doi:10.1192/bjp.169.4.459. PMID 8894197. S2CID 3086394.

- ^ a b c d Manford M, Andermann F (October 1998). "Complex visual hallucinations. Clinical and neurobiological insights". Brain. 121 ( Pt 10) (10): 1819–1840. doi:10.1093/brain/121.10.1819. PMID 9798740.

- ^ Rahman A, Paul M (2023). "Delirium Tremens". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29489272. Archived from the original on 2023-12-04. Retrieved 2024-01-08.

- ^ Grover S, Ghosh A (December 2018). "Delirium Tremens: Assessment and Management". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 8 (4): 460–470. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2018.04.012. PMC 6286444. PMID 30564004.

- ^ Franchina P (2023-06-30). "Presence Hallucinations as an Early Indicator of Cognitive Decline in Parkinson's Disease". American Parkinson Disease Association. Retrieved 2024-07-27.

- ^ Derr D (14 February 2006). "Marilyn and Me". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-09-26.

- ^ Zegar A (2022-12-15). "Migraine Doctor Rice Village 77005". Rice Emergency Room. Retrieved 2024-07-27.

- ^ Engmann B (2008). "Phosphene und Photopsien – Okzipitallappeninfarkt oder Reizdeprivation?" [Phosphenes and photopsias - ischaemic origin or sensorial deprivation? - Case history]. Zeitschrift für Neuropsychologie (in German). 19 (1): 7–13. doi:10.1024/1016-264X.19.1.7.

- ^ Teeple RC, Caplan JP, Stern TA (2009). "Visual hallucinations: differential diagnosis and treatment". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 11 (1): 26–32. doi:10.4088/PCC.08r00673. PMC 2660156. PMID 19333408.

- ^ Bien CG, Benninger FO, Urbach H, Schramm J, Kurthen M, Elger CE (February 2000). "Localizing value of epileptic visual auras". Brain. 123 ( Pt 2) (2): 244–253. doi:10.1093/brain/123.2.244. PMID 10648433.

- ^ Teeple RC, Caplan JP, Stern TA (2009-02-15). "Visual Hallucinations: Differential Diagnosis and Treatment". The Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 11 (1): 26–32. doi:10.4088/PCC.08r00673. ISSN 1523-5998. PMC 2660156. PMID 19333408.

- ^ "Fentanyl (Transdermal Route) Side Effects - Mayo Clinic". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2018-04-24. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ "Talwin Injection - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". Archived from the original on 2018-04-24. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ "Prescription Drugs That Can Cause Hallucinations". azcentral.com. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ Trauner R, Obwegeser H (July 1957). "The surgical correction of mandibular prognathism and retrognathia with consideration of genioplasty. I. Surgical procedures to correct mandibular prognathism and reshaping of the chin". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 10 (7): 677–89, contd. doi:10.1016/S0030-4220(57)80063-2. PMID 13441284.

- ^ Mason OJ, Brady F (October 2009). "The psychotomimetic effects of short-term sensory deprivation". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 197 (10): 783–785. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b9760b. PMID 19829208. S2CID 23079468.

- ^ Gurney E, Myers FW, Podmore F (1886). Phantasms of the Living, Vols. I and II. London: Trubner and Co.

- ^ Sidgwick E, Johnson A, et al. (1894). "Report on the Census of Hallucinations". Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research. X. London.

- ^ Slade PD, Bentall RP (1988). Sensory Deception: a scientific analysis of hallucination. London: Croom Helm.

- ^ Losurdo G, Principi M, Iannone A, Amoruso A, Ierardi E, Di Leo A, et al. (April 2018). "Extra-intestinal manifestations of non-celiac gluten sensitivity: An expanding paradigm". World Journal of Gastroenterology (Review). 24 (14): 1521–1530. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i14.1521. PMC 5897856. PMID 29662290.

- ^ a b Brown GG, Thompson WK (2010). "Functional Brain Imaging in Schizophrenia: Selected Results and Methods". Behavioral Neurobiology of Schizophrenia and Its Treatment. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 4. pp. 181–214. doi:10.1007/7854_2010_54. ISBN 978-3-642-13716-7. PMID 21312401.

- ^ El Haj M, Roche J, Jardri R, Kapogiannis D, Gallouj K, Antoine P (December 2017). "Clinical and neurocognitive aspects of hallucinations in Alzheimer's disease". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 83: 713–720. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.021. PMC 5565710. PMID 28235545.

- ^ Boksa P (July 2009). "On the neurobiology of hallucinations". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 34 (4): 260–262. PMC 2702442. PMID 19568476.

- ^ Kumar S, Soren S, Chaudhury S (July 2009). "Hallucinations: Etiology and clinical implications". Industrial Psychiatry Journal. 18 (2): 119–126. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.62273. PMC 2996210. PMID 21180490.

- ^ Behrendt RP (May 2006). "Dysregulation of thalamic sensory "transmission" in schizophrenia: neurochemical vulnerability to hallucinations". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 20 (3): 356–372. doi:10.1177/0269881105057696. PMID 16174672. S2CID 17104995.

- ^ Aleman A, Vercammon A. "The Bottom Up and Top Down Components of Hallucinatory Phenomenon". In Jardri R, Cachia A, Pins D, Thomas P (eds.). The Neuroscience of Hallucinations. Springer.

- ^ "Hallucinations: Definition, Causes, Treatment & Types". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 2024-01-08. Retrieved 2024-01-08.

- ^ Wikipedia contributors (February 2024). "Hearing Voices Movement". Archived from the original on 2023-11-28. Retrieved 2024-03-03.

- ^ a b c de Leede-Smith S, Barkus E (2013). "A comprehensive review of auditory verbal hallucinations: lifetime prevalence, correlates and mechanisms in healthy and clinical individuals". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 7: 367. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00367. PMC 3712258. PMID 23882203.

- ^ a b c Maijer K, Begemann MJ, Palmen SJ, Leucht S, Sommer IE (April 2018). "Auditory hallucinations across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Psychological Medicine. 48 (6): 879–888. doi:10.1017/s0033291717002367. PMID 28956518. S2CID 3820537.

- ^ Bunevičius P, Stompe R, Adomaitienė T, Vaškelytė V, Kupčinskas JJ, Stakišaitis L, et al. (2008-09-08). The impact of personal religiosity and culture on the content of delusions and hallucinations in schizophrenia. Lithuanian Academic Libraries Network (LABT). OCLC 654554799.

- ^ a b Maijer K, Hayward M, Fernyhough C, Calkins ME, Debbané M, Jardri R, et al. (2019-02-01). "Hallucinations in Children and Adolescents: An Updated Review and Practical Recommendations for Clinicians". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 45 (45 Suppl 1): S5 – S23. doi:10.1093/schbul/sby119. ISSN 1745-1701. PMC 6357982. PMID 30715540.

- ^ Linszen MM, van Zanten GA, Teunisse RJ, Brouwer RM, Scheltens P, Sommer IE (January 2019). "Auditory hallucinations in adults with hearing impairment: a large prevalence study" (PDF). Psychological Medicine. 49 (1): 132–139. doi:10.1017/S0033291718000594. PMID 29554989.

- ^ a b c Cook CC (June 2015). "Religious psychopathology: The prevalence of religious content of delusions and hallucinations in mental disorder". The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 61 (4): 404–425. doi:10.1177/0020764015573089. PMC 4440877. PMID 25770205.

Further reading

[edit]- Johnson FH (1978). The Anatomy of Hallucinations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. ISBN 0-88229-155-6.

- Slade PD, Bentall RP (1988). Sensory Deception: A Scientific Analysis of Hallucination. London Sydney: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7099-3961-2.

- Aleman A, Larøi F (2008). Hallucinations: The Science of Idiosyncratic Perception. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-4338-0311-6.

- Sacks OW (2012). Hallucinations (1. American ed.). New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-95724-5.

External links

[edit]- Hearing Voices Network

- "Anthropology and Hallucinations; chapter from The Making of Religion". psychanalyse-paris.com. November 4, 2006. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- Hallucination: A Normal Phenomenon?

- Geometric visual hallucinations, Euclidean symmetry and the functional architecture of striate cortex