Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Baleen

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2025) |

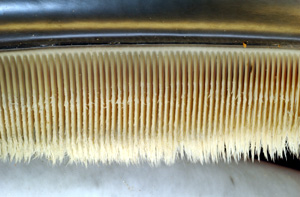

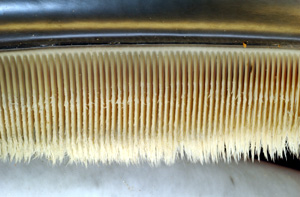

Baleens, also referred to as "Baleen plates", are triangular sheets of keratin that make up a filter-feeding system (the "Baleen rack") inside the mouth of baleen whales. The feeding process starts as the animal opens its mouth to take in water. The whale then pushes the water out through a rack of baleen plates, so as to retain (filter) what will serve as food for the whale. A baleen is similar to a bristle and consists of keratin, the same substance found in human fingernails, skin and hair.[citation needed] Some whales, such as the bowhead whale, have baleen of differing lengths. Other whales, such as the gray whale, only use one side of their baleen. These baleen bristles are arranged in plates across the upper jaw of whales.

Depending on the species, a baleen plate can be 0.5 to 3.5 m (1.6 to 11.5 ft) long, and weigh up to 90 kg (200 lb). Its hairy fringes are called baleen hair or whalebone hair. They are also called baleen bristles, which in sei whales are highly calcified, with calcification functioning to increase their stiffness.[1][2] Baleen plates are broader at the gumline (base). The plates have been compared to sieves or Venetian blinds.

As a material for various human uses, baleen is usually called whalebone, which is a misnomer.

Etymology

[edit]The word "baleen" derives from the Latin bālaena, related to the Greek phalaina – both of which mean "whale".

Evolution

[edit]The oldest true fossils of baleen are only 15 million years old because baleen rarely fossilizes, but scientists believe it originated considerably earlier than that.[3] This is indicated by baleen-related skull modifications being found in fossils from considerably earlier, including a buttress of bone in the upper jaw beneath the eyes, and loose lower jaw bones at the chin. Baleen is believed to have evolved around 30 million years ago, possibly from a hard, gummy upper jaw, like the one a Dall's porpoise has; it closely resembles baleen at the microscopic level. The initial evolution and radiation of baleen plates is believed to have occurred during Early Oligocene when Antarctica broke off from Gondwana and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current was formed, increasing productivity of ocean environments.[4] This occurred because the current kept warm ocean waters away from the area that is now Antarctica, producing steep gradients in temperature, salinity, light, and nutrients, where the warm water meets the cold.[5]

The transition from teeth to baleen is proposed to have occurred stepwise, from teeth to a hybrid to baleen. It is known that modern mysticetes have teeth initially and then develop baleen plate germs in utero, but lose their dentition and have only baleen during their juvenile years and adulthood. However, developing mysticetes do not produce tooth enamel because at some point this trait evolved to become a pseudogene. This is likely to have occurred about 28 million years ago and proves that dentition is an ancestral state of mysticetes. Using parsimony to study this and other ancestral characters suggests that the common ancestor of aetiocetids and edentulous mysticetes evolved lateral nutrient foramina, which are believed to have provided blood vessels and nerves a way to reach developing baleen. Further research suggests that the baleen of Aetiocetus was arranged in bundles between widely spaced teeth. If true, this combination of baleen and dentition in Aetiocetus would act as a transition state between odontocetes and mysticetes. This intermediate step is further supported by evidence of other changes that occurred with the evolution of baleen that make it possible for the organisms to survive using filter feeding, such as a change in skull structure and throat elasticity. It would be highly unlikely for all of these changes to occur at once. Therefore, it is proposed that Oligocene aetiocetids possess both ancestral and descendant character states regarding feeding strategies. This makes them mosaic taxa, showing that either baleen evolved before dentition was lost or that the traits for filter feeding originally evolved for other functions. It also shows that the evolution could have occurred gradually because the ancestral state was originally maintained. Therefore, the mosaic whales could have exploited new resources using filter feeding while not abandoning their previous prey strategies. The result of this stepwise transition is apparent in modern-day baleen whales, because of their enamel pseudogenes and their in utero development and reabsorbing of teeth.[3]

If it is true that many early baleen whales also had teeth, these were probably used only peripherally, or perhaps not at all (again like Dall's porpoise, which catches squid and fish by gripping them against its hard upper jaw). Intense research has been carried out to sort out the evolution and phylogenetic history of mysticetes, but much debate surrounds this issue.

Filter feeding

[edit]A whale's baleen plates play the most important role in its filter-feeding process. To feed, a baleen whale opens its mouth widely and scoops in dense shoals of prey (such as krill, copepods, small fish, and sometimes birds that happen to be near the shoals), together with large volumes of water. It then partly shuts its mouth and presses its tongue against its upper jaw, forcing the water to pass out sideways through the baleen, thus sieving out the prey, which it then swallows.

Mechanical properties

[edit]Whale baleen is the mostly mineralized keratin-based bio-material consisting of parallel plates suspended down the mouth of the whale. Baleen's mechanical properties of being strong and flexible made it a popular material for numerous applications requiring such a property (see Human uses section).

The basic structure of the whale baleen has been described as a tubular structure with a hollow medulla (inner core) enclosed by a tubular layer with a diameter varying from 60 to 900 micrometres, which had approximately 2.7 times higher calcium content than the outer solid shell. The elastic modulus in the longitudinal direction and the transverse direction are 270 megapascals (MPa) and 200 MPa, respectively. This difference in the elastic moduli could[clarification needed] be attributed to the way the sandwiched tubular structures are packed together.

Hydrated versus dry whale baleen also exhibit significantly different parallel and perpendicular compressive stress to compressive strain response. Although parallel loading for both hydrated and dry samples exhibit higher stress response (about 20 MPa and 140 MPa at 0.07 strain for hydrated and dry samples respectively) than that for perpendicular loading, hydration drastically reduced the compressive response.[6]

Crack formation is also different for both the transverse and longitudinal orientation. For the transverse direction, cracks are redirected along the tubules, which enhances the baleen's resistance to fracture and once the crack enters the tubule it is then directed along the weaker interface rather than penetrating through either the tubule or lamellae.

Human uses

[edit]

People formerly used baleen (usually referred to as "whalebone") for making numerous items where flexibility and strength were required, including baskets, backscratchers, collar stiffeners, buggy whips, parasol ribs, switches, crinoline petticoats, farthingales, busks, and corset stays,[7] but also pieces of armour.[8] It was commonly used to crease paper; its flexibility kept it from damaging the paper. It was also occasionally used in cable-backed bows. Synthetic materials are now usually used for similar purposes, especially plastic and fiberglass. Baleen was also used by Dutch cabinetmakers for the production of pressed reliefs.[9]

In the United States, the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972 makes it illegal "for any person to transport, purchase, sell, export, or offer to purchase, sell, or export any marine mammal or marine mammal product".[10]

See also

[edit]- John Henry Devereux, a South Carolina architect who used whale jaw bones to adorn the largest mansion on Sullivan's Island

References

[edit]- ^ Fudge, Douglas S.; Szewciw, Lawrence J.; Schwalb, Astrid N. (2009). "Morphology and Development of Blue Whale Baleen: An Annotated Translation of Tycho Tullberg's Classic 1883 Paper" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 35 (2): 226–52. doi:10.1578/AM.35.2.2009.226.

- ^ Szewciw, L. J.; De Kerckhove, D. G.; Grime, G. W.; Fudge, D. S. (2010). "Calcification provides mechanical reinforcement to whale baleen -keratin" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1694): 2597–605. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0399. PMC 2982044. PMID 20392736. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-25.

- ^ a b Deméré, Thomas; Michael R. McGowen; Annalisa Berta; John Gatesy (September 2007). "Morphological and Molecular Evidence for a Stepwise Evolutionary Transition from Teeth to Baleen in Mysticete Whales". Systematic Biology. 57 (1): 15–37. doi:10.1080/10635150701884632. PMID 18266181.

- ^ Marx, Felix G. (19 February 2010). "Climate, critters and cetaceans: cenozoic drivers of the evolution of modern whales" (PDF). Science. 327 (5968): 993–996. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..993M. doi:10.1126/science.1185581. PMID 20167785. S2CID 21797084.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Erich M.G. (15 August 2006). "A bizarre new toothed mysticete (Cetacea) from Australia and the early evolution of baleen whales". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1604): 2955–2963. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3664. PMC 1639514. PMID 17015308.

- ^ Wang, Bin; Sullivan, Tarah N.; Pissarenko, Andrei; Zaheri, Alireza; Espinosa, Horacio D.; Meyers, Marc A. (19 November 2018). "Lessons from the Ocean: Whale Baleen Fracture Resistance". Advanced Materials. 31 (3) 1804574. doi:10.1002/adma.201804574. PMID 30450716.

- ^ Sarah A. Bendall, "Whalebone and the Wardrobe of Elizabeth I: Whaling and the Making of Aristocratic Fashions in Sixteenth Century Europe", Apparence(s), 11 (2022). doi:10.4000/apparences.3653

- ^ Lee Raye, "Evidence for the use of whale-baleen products in medieval Powys, Wales", Medieval Animal Data Network (blog on Hypotheses.org), June, 26th, 2014. online

- ^ BREEBAART, Iskander; VAN GERVEN, Gert (2013). "Pressed baleen and fan-shaped ripple mouldings by Herman Doomer". Eleventh International Symposium on Wood and Furniture Conservation Amsterdam 9–10 November 2012. Amsterdam. Stichting Ebenist: 62–74.

- ^ Fisheries, NOAA (2021-04-27). "Marine Mammal Protection Act | NOAA Fisheries". NOAA. Retrieved 2021-05-08.

Further reading

[edit]- St. Aubin, D. J.; Stinson, R. H.; Geraci, J. R. (1984). "Aspects of the structure and composition of baleen, and some effects of exposure to petroleum hydrocarbons" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 62 (2): 193–8. doi:10.1139/z84-032.

- Meredith, Robert W.; Gatesy, John; Cheng, Joyce; Springer, Mark S. (2010). "Pseudogenization of the tooth gene enamelysin (MMP20) in the common ancestor of extant baleen whales". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1708): 993–1002. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1280. PMC 3049022. PMID 20861053.

- "How baleen whales lost a gene and their teeth". Thoughtomics. Archived from the original on 2011-03-22.

External links

[edit]- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.