Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

12 equal temperament

View on Wikipedia

12 equal temperament (12-ET)[a] is the musical system that divides the octave into 12 parts, all of which are equally tempered (equally spaced) on a logarithmic scale, with a ratio equal to the 12th root of 2 ( ≈ 1.05946). That resulting smallest interval, 1⁄12 the width of an octave, is called a semitone or half step.

Twelve-tone equal temperament is the most widespread system in music today. It has been the predominant tuning system of Western music, starting with classical music, since the 18th century, and Europe almost exclusively used approximations of it for millennia before that.[citation needed] It has also been used in other cultures.

In modern times, 12-ET is usually tuned relative to a standard pitch of 440 Hz, called A440, meaning one note, A4 (the A in the 4th octave of a typical 88-key piano), is tuned to 440 hertz and all other notes are defined as some multiple of semitones apart from it, either higher or lower in frequency. The standard pitch has not always been 440 Hz. It has varied and generally risen over the past few hundred years.[1]

History

[edit]The two figures frequently credited with the achievement of exact calculation of twelve-tone equal temperament are Zhu Zaiyu (also romanized as Chu-Tsaiyu, Chinese: 朱載堉) in 1584 and Simon Stevin in 1585. According to Fritz A. Kuttner, a critic of the theory,[2] it is known that "Chu-Tsaiyu presented a highly precise, simple and ingenious method for arithmetic calculation of equal temperament mono-chords in 1584" and that "Simon Stevin offered a mathematical definition of equal temperament plus a somewhat less precise computation of the corresponding numerical values in 1585 or later." The developments occurred independently.[3]

Kenneth Robinson attributes the invention of equal temperament to Zhu Zaiyu[4] and provides textual quotations as evidence.[5] Zhu Zaiyu is quoted as saying that, in a text dating from 1584, "I have founded a new system. I establish one foot as the number from which the others are to be extracted, and using proportions I extract them. Altogether one has to find the exact figures for the pitch-pipers in twelve operations."[5] Kuttner disagrees and remarks that his claim "cannot be considered correct without major qualifications."[2] Kuttner proposes that neither Zhu Zaiyu or Simon Stevin achieved equal temperament and that neither of the two should be treated as inventors.[3]

China

[edit]Early history

[edit]A complete set of bronze chime bells, among many musical instruments found in the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng (early Warring States, c. 5th century BCE in the Chinese Bronze Age), covers five full 7-note octaves in the key of C Major, including 12 note semi-tones in the middle of the range.[6]

An approximation for equal temperament was described by He Chengtian, a mathematician of the Southern and Northern Dynasties who lived from 370 to 447.[7] He came out with the earliest recorded approximate numerical sequence in relation to equal temperament in history: 900 849 802 758 715 677 638 601 570 536 509.5 479 450.[8]

Zhu Zaiyu

[edit]

Zhu Zaiyu (朱載堉), a prince of the Ming court, spent thirty years on research based on the equal temperament idea originally postulated by his father. He described his new pitch theory in his Fusion of Music and Calendar 律暦融通 published in 1580. This was followed by the publication of a detailed account of the new theory of the equal temperament with a precise numerical specification for 12-ET in his 5,000-page work Complete Compendium of Music and Pitch (Yuelü quan shu 樂律全書) in 1584.[9] An extended account is also given by Joseph Needham.[5] Zhu obtained his result mathematically by dividing the length of string and pipe successively by 12√2 ≈ 1.059463, and for pipe length by 24√2,[10] such that after twelve divisions (an octave) the length was divided by a factor of 2:

Similarly, after 84 divisions (7 octaves) the length was divided by a factor of 128:

Zhu Zaiyu has been credited as the first person to solve the equal temperament problem mathematically.[11] At least one researcher has proposed that Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit in China recorded this work in his personal journal[11][12] and may have transmitted the work back to Europe. (Standard resources on the topic make no mention of any such transfer.[13]) In 1620, Zhu's work was referenced by a European mathematician.[who?][12] Murray Barbour said, "The first known appearance in print of the correct figures for equal temperament was in China, where Prince Tsaiyü's brilliant solution remains an enigma."[14] The 19th-century German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz wrote in On the Sensations of Tone that a Chinese prince (see below) introduced a scale of seven notes, and that the division of the octave into twelve semitones was discovered in China.[15]

Zhu Zaiyu illustrated his equal temperament theory by the construction of a set of 36 bamboo tuning pipes ranging in 3 octaves, with instructions of the type of bamboo, color of paint, and detailed specification on their length and inner and outer diameters. He also constructed a 12-string tuning instrument, with a set of tuning pitch pipes hidden inside its bottom cavity. In 1890, Victor-Charles Mahillon, curator of the Conservatoire museum in Brussels, duplicated a set of pitch pipes according to Zhu Zaiyu's specification. He said that the Chinese theory of tones knew more about the length of pitch pipes than its Western counterpart, and that the set of pipes duplicated according to the Zaiyu data proved the accuracy of this theory.

Europe

[edit]

Early history

[edit]One of the earliest discussions of equal temperament occurs in the writing of Aristoxenus in the 4th century BC.[16]

Vincenzo Galilei (father of Galileo Galilei) was one of the first practical advocates of twelve-tone equal temperament. He composed a set of dance suites on each of the 12 notes of the chromatic scale in all the "transposition keys", and published also, in his 1584 "Fronimo", 24 + 1 ricercars.[17] He used the 18:17 ratio for fretting the lute (although some adjustment was necessary for pure octaves).[18]

Galilei's countryman and fellow lutenist Giacomo Gorzanis had written music based on equal temperament by 1567.[19] Gorzanis was not the only lutenist to explore all modes or keys: Francesco Spinacino wrote a "Recercare de tutti li Toni" (Ricercar in all the Tones) as early as 1507.[20] In the 17th century lutenist-composer John Wilson wrote a set of 30 preludes including 24 in all the major/minor keys.[21][22] Henricus Grammateus drew a close approximation to equal temperament in 1518. The first tuning rules in equal temperament were given by Giovani Maria Lanfranco in his "Scintille de musica".[23] Zarlino in his polemic with Galilei initially opposed equal temperament but eventually conceded to it in relation to the lute in his Sopplimenti musicali in 1588.

Simon Stevin

[edit]The first mention of equal temperament related to the twelfth root of two in the West appeared in Simon Stevin's manuscript Van De Spiegheling der singconst (c. 1605), published posthumously nearly three centuries later in 1884.[24] However, due to insufficient accuracy of his calculation, many of the chord length numbers he obtained were off by one or two units from the correct values.[13] As a result, the frequency ratios of Simon Stevin's chords has no unified ratio, but one ratio per tone, which is claimed by Gene Cho as incorrect.[25]

The following were Simon Stevin's chord length from Van de Spiegheling der singconst:[26]

| Tone | Chord 10000 from Simon Stevin | Ratio | Corrected chord |

|---|---|---|---|

| semitone | 9438 | 1.0595465 | 9438.7 |

| whole tone | 8909 | 1.0593781 | |

| tone and a half | 8404 | 1.0600904 | 8409 |

| ditone | 7936 | 1.0594758 | 7937 |

| ditone and a half | 7491 | 1.0594046 | 7491.5 |

| tritone | 7071 | 1.0593975 | 7071.1 |

| tritone and a half | 6674 | 1.0594845 | 6674.2 |

| four-tone | 6298 | 1.0597014 | 6299 |

| four-tone and a half | 5944 | 1.0595558 | 5946 |

| five-tone | 5611 | 1.0593477 | 5612.3 |

| five-tone and a half | 5296 | 1.0594788 | 5297.2 |

| full tone | 1.0592000 |

A generation later, French mathematician Marin Mersenne presented several equal tempered chord lengths obtained by Jean Beaugrand, Ismael Bouillaud, and Jean Galle.[27]

In 1630 Johann Faulhaber published a 100-cent monochord table, which contained several errors due to his use of logarithmic tables. He did not explain how he obtained his results.[28]

Baroque era

[edit]From 1450 to about 1800, plucked instrument players (lutenists and guitarists) generally favored equal temperament,[29] and the Brossard lute manuscript compiled in the last quarter of the 17th century contains a series of 18 preludes attributed to Bocquet written in all keys, including the last prelude, entitled Prélude sur tous les tons, which enharmonically modulates through all keys.[30][clarification needed] Angelo Michele Bartolotti published a series of passacaglias in all keys, with connecting enharmonically modulating passages. Among the 17th-century keyboard composers Girolamo Frescobaldi advocated equal temperament. Some theorists, such as Giuseppe Tartini, were opposed to the adoption of equal temperament; they felt that degrading the purity of each chord degraded the aesthetic appeal of music, although Andreas Werckmeister emphatically advocated equal temperament in his 1707 treatise published posthumously.[31]

Twelve-tone equal temperament took hold for a variety of reasons. It was a convenient fit for the existing keyboard design, and permitted total harmonic freedom with the burden of moderate impurity in every interval, particularly imperfect consonances. This allowed greater expression through enharmonic modulation, which became extremely important in the 18th century in music of such composers as Francesco Geminiani, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach, and Johann Gottfried Müthel.[citation needed] Twelve-tone equal temperament did have some disadvantages, such as imperfect thirds, but as Europe switched to equal temperament, it changed the music that it wrote in order to accommodate the system and minimize dissonance.[b]

The progress of equal temperament from the mid-18th century on is described with detail in quite a few modern scholarly publications: It was already the temperament of choice during the Classical era (second half of the 18th century),[citation needed] and it became standard during the Early Romantic era (first decade of the 19th century),[citation needed] except for organs that switched to it more gradually, completing only in the second decade of the 19th century. (In England, some cathedral organists and choirmasters held out against it even after that date; Samuel Sebastian Wesley, for instance, opposed it all along. He died in 1876.)[citation needed]

A precise equal temperament is possible using the 17th century Sabbatini method of splitting the octave first into three tempered major thirds.[32] This was also proposed by several writers during the Classical era. Tuning without beat rates but employing several checks, achieving virtually modern accuracy, was already done in the first decades of the 19th century.[33] Using beat rates, first proposed in 1749, became common after their diffusion by Helmholtz and Ellis in the second half of the 19th century.[34] The ultimate precision was available with 2 decimal tables published by White in 1917.[35]

It is in the environment of equal temperament that the new styles of symmetrical tonality and polytonality, atonal music such as that written with the twelve tone technique or serialism, and jazz (at least its piano component) developed and flourished.

Comparison of historical approximations of the semitone

[edit]| Year | Name | Ratio[36] | Cents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 | He Chengtian | 1.060070671 | 101.0 |

| 1580 | Vincenzo Galilei | 18:17 [1.058823529] | 99.0 |

| 1581 | Zhu Zaiyu | 1.059463094 | 100.0 |

| 1585 | Simon Stevin | 1.059546514 | 100.1 |

| 1630 | Marin Mersenne | 1.059322034 | 99.8 |

| 1630 | Johann Faulhaber | 1.059490385 | 100.0 |

Mathematical properties

[edit]

In twelve-tone equal temperament, which divides the octave into 12 equal parts, the width of a semitone, i.e. the frequency ratio of the interval between two adjacent notes, is the twelfth root of two:

This interval is divided into 100 cents.

Calculating absolute frequencies

[edit]To find the frequency, Pn, of a note in 12-ET, the following definition may be used:

In this formula Pn refers to the pitch, or frequency (usually in hertz), you are trying to find. Pa refers to the frequency of a reference pitch. n and a refer to numbers assigned to the desired pitch and the reference pitch, respectively. These two numbers are from a list of consecutive integers assigned to consecutive semitones. For example, A4 (the reference pitch) is the 49th key from the left end of a piano (tuned to 440 Hz), and C4 (middle C), and F#4 are the 40th and 46th key respectively. These numbers can be used to find the frequency of C4 and F#4:

Just intervals

[edit]

The intervals of 12-ET closely approximate some intervals in just intonation.[37]

By limit

[edit]12 ET is very accurate in the 3 limit, but as one increases prime limits to 11, it gradually gets worse by about a sixth of a semitone each time. Its eleventh and thirteenth harmonics are extremely inaccurate. 12 ET's seventeenth and nineteenth harmonics are almost as accurate as its third harmonic, but by this point, the prime limit has gotten too high to sound consonant to most people.[citation needed]

3 limit

[edit]12 ET has a very good approximation of the perfect fifth ( 3 /2) and its inversion, the perfect fourth ( 4 /3), especially for the division of the octave into a relatively small number of tones. Specifically, a just perfect fifth is only one fifty-first of a semitone sharper than the equally-tempered approximation. Because the major tone ( 9 /8) is simply two perfect fifths minus an octave, and its inversion, the Pythagorean minor seventh ( 16 /9), is simply two perfect fourths combined, they, for the most part, retain the accuracy of their predecessors; the error is doubled, but it remains small – so small, in fact, that humans cannot perceive it. One can continue to use fractions with higher powers of three, the next two being 27 /16 and 32 /27, but as the terms of the fractions grow larger, they become less pleasing to the ear.[citation needed]

5 limit

[edit]12 ET's approximation of the fifth harmonic ( 5 /4) is approximately one-seventh of a semitone off. Because intervals that are less than a quarter of a scale step off still sound in tune, other five-limit intervals in 12 ET, such as 5 /3 and 8 /5, have similarly sized errors. The major triad, therefore, sounds in tune as its frequency ratio is approximately 4:5:6, further, merged with its first inversion, and two sub-octave tonics, it is 1:2:3:4:5:6, all six lowest natural harmonics of the bass tone.[citation needed]

7 limit

[edit]12 ET's approximation of the seventh harmonic ( 7 /4) is about one-third of a semitone off. Because the error is greater than a quarter of a semitone, seven-limit intervals in 12 ET tend to sound out of tune. In the tritone fractions 7 /5 and 10 /7, the errors of the fifth and seventh harmonics partially cancel each other out so that the just fractions are within a quarter of a semitone of their equally-tempered equivalents.[citation needed]

11 and 13 limits

[edit]The eleventh harmonic ( 11 /8), at 551.32 cents, falls almost exactly halfway between the nearest two equally-tempered intervals in 12 ET and therefore is not approximated by either. In fact, 11 /8 is almost as far from any equally-tempered approximation as possible in 12 ET. The thirteenth harmonic ( 13 /8), at two-fifths of a semitone sharper than a minor sixth, is almost as inaccurate. Although this means that the fraction 13 /11 and also its inversion ( 22 /13) are accurately approximated (specifically, by three semitones), since the errors of the eleventh and thirteenth harmonics mostly cancel out, most people who are not familiar with quarter tones or microtonality will not be familiar with the eleventh and thirteenth harmonics. Similarly, while the error of the eleventh or thirteenth harmonic could be mostly canceled out by the error of the seventh harmonic, most Western musicians would not find the resulting fractions consonant since 12 ET does not approximate them accurately.[citation needed]

17 and 19 limits

[edit]The seventeenth harmonic ( 17 /16) is only about 5 cents sharper than one semitone in 12 ET. It can be combined with 12 ET's approximation of the third harmonic in order to yield 17 /12, which is, as the next Pell approximation after 7 /5, only about three cents away from the equally-tempered tritone (the square root of two), and 17 /9, which is only one cent away from 12 ET's major seventh. The nineteenth harmonic is only about 2.5 cents flatter than three of 12 ET's semitones, so it can likewise be combined with the third harmonic to yield 19 /12, which is about 4.5 cents flatter than an equally-tempered minor sixth, and 19 /18, which is about 6.5 cents flatter than a semitone. However, because 17 and 19 are rather large for consonant ratios and most people are unfamiliar with 17 limit and 19 limit intervals, 17 limit and 19 limit intervals are not useful for most purposes, so they can likely not be judged as playing a part in any consonances of 12 ET.[citation needed]

Table

[edit]In the following table the sizes of various just intervals are compared against their equal-tempered counterparts, given as a ratio as well as cents. Differences of less than six cents cannot be noticed by most people, and intervals that are more than a quarter of a step; which in this case is 25 cents, off sound out of tune.[citation needed]

| Number of half steps | Note going up from C | Exact value in 12-ET | Decimal value in 12-ET | Equally-tempered audio | Cents | Just intonation interval name | Just intonation interval fraction | Justly-intoned audio | Cents in just intonation | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | C | 20⁄12 = 1 | 1 | ⓘ | 0 | Unison | 1⁄1 = 1 | ⓘ | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | C♯ or D♭ | 21⁄12 = | 1.05946... | ⓘ | 100 | Septimal third tone | 28⁄27 = 1.03703... | ⓘ | 62.96 | −37.04 |

| Just chromatic semitone | 25⁄24 = 1.04166... | ⓘ | 70.67 | −29.33 | ||||||

| Undecimal semitone | 22⁄21 = 1.04761... | ⓘ | 80.54 | −19.46 | ||||||

| Septimal chromatic semitone | 21⁄ 20 = 1.05 | ⓘ | 84.47 | −15.53 | ||||||

| Novendecimal chromatic semitone | 20⁄ 19 = 1.05263... | ⓘ | 88.80 | −11.20 | ||||||

| Pythagorean diatonic semitone | 256⁄ 243 = 1.05349... | ⓘ | 90.22xwx | −9.78 | ||||||

| Larger chromatic semitone | 135⁄ 128 = 1.05468... | ⓘ | 92.18 | −7.82 | ||||||

| Novendecimal diatonic semitone | 19⁄ 18 = 1.05555... | ⓘ | 93.60 | −6.40 | ||||||

| Septadecimal chromatic semitone | 18⁄ 17 = 1.05882... | ⓘ | 98.95 | −1.05 | ||||||

| Seventeenth harmonic | 17⁄ 16 = 1.0625... | ⓘ | 104.96 | +4.96 | ||||||

| Just diatonic semitone | 16⁄ 15 = 1.06666... | ⓘ | 111.73 | +11.73 | ||||||

| Pythagorean chromatic semitone | 2187⁄ 2048 = 1.06787... | ⓘ | 113.69 | +13.69 | ||||||

| Septimal diatonic semitone | 15⁄ 14 = 1.07142... | ⓘ | 119.44 | +19.44 | ||||||

| Lesser tridecimal 2/3-tone | 14⁄ 13 = 1.07692... | ⓘ | 128.30 | +28.30 | ||||||

| Major diatonic semitone | 27⁄ 25 = 1.08 | ⓘ | 133.24 | +33.24 | ||||||

| 2 | D | 2 2⁄ 12 = | 1.12246... | ⓘ | 200 | Pythagorean diminished third | 65536⁄ 59049 = 1.10985... | ⓘ | 180.45 | −19.55 |

| Minor tone | 10⁄ 9 = 1.11111... | ⓘ | 182.40 | −17.60 | ||||||

| Major tone | 9⁄ 8 = 1.125 | ⓘ | 203.91 | +3.91 | ||||||

| Septimal whole tone | 8⁄ 7 = 1.14285... | ⓘ | 231.17 | +31.17 | ||||||

| 3 | D♯ or E♭ | 2 3⁄ 12 = | 1.18920... | ⓘ | 300 | Septimal minor third | 7⁄ 6 = 1.16666... | ⓘ | 266.87 | −33.13 |

| Tridecimal minor third | 13⁄ 11 = 1.18181... | ⓘ | 289.21 | −10.79 | ||||||

| Pythagorean minor third | 32⁄ 27 = 1.18518... | ⓘ | 294.13 | −5.87 | ||||||

| Nineteenth harmonic | 19⁄ 16 = 1.1875 | ⓘ | 297.51 | −2.49 | ||||||

| Just minor third | 6⁄ 5 = 1.2 | ⓘ | 315.64 | +15.64 | ||||||

| Pythagorean augmented second | 19683⁄ 16384 = 1.20135... | ⓘ | 317.60 | +17.60 | ||||||

| 4 | E | 2 4⁄ 12 = | 1.25992... | ⓘ | 400 | Pythagorean diminished fourth | 8192⁄ 6561 = 1.24859... | ⓘ | 384.36 | −15.64 |

| Just major third | 5⁄ 4 = 1.25 | ⓘ | 386.31 | −13.69 | ||||||

| Pythagorean major third | 81⁄ 64 = 1.265625 | ⓘ | 407.82 | +7.82 | ||||||

| Undecimal major third | 14⁄ 11 = 1.27272... | ⓘ | 417.51 | +17.51 | ||||||

| Septimal major third | 9⁄ 7 = 1.28571... | ⓘ | 435.08 | +35.08 | ||||||

| 5 | F | 2 5⁄ 12 = | 1.33484... | ⓘ | 500 | Just perfect fourth | 4⁄ 3 = 1.33333... | ⓘ | 498.04 | −1.96 |

| Pythagorean augmented third | 177147⁄ 131072 = 1.35152... | ⓘ | 521.51 | +21.51 | ||||||

| 6 | F♯ or G♭ | 2 6⁄ 12 = | 1.41421... | ⓘ | 600 | Classic augmented fourth | 25⁄ 18 = 1.38888... | ⓘ | 568.72 | −31.28 |

| Huygens' tritone | 7⁄ 5 = 1.4 | ⓘ | 582.51 | −17.49 | ||||||

| Pythagorean diminished fifth | 1024⁄ 729 = 1.40466... | ⓘ | 588.27 | −11.73 | ||||||

| Just augmented fourth | 45⁄ 32 = 1.40625 | ⓘ | 590.22 | −9.78 | ||||||

| Just diminished fifth | 64⁄ 45 = 1.42222... | ⓘ | 609.78 | +9.78 | ||||||

| Pythagorean augmented fourth | 729⁄ 512 = 1.42382... | ⓘ | 611.73 | +11.73 | ||||||

| Euler's tritone | 10⁄ 7 = 1.42857... | ⓘ | 617.49 | +17.49 | ||||||

| Classic diminished fifth | 36⁄ 25 = 1.44 | ⓘ | 631.28 | +31.28 | ||||||

| 7 | G | 2 7⁄ 12 = | 1.49830... | ⓘ | 700 | Pythagorean diminished sixth | 262144⁄ 177147 = 1.47981... | ⓘ | 678.49 | −21.51 |

| Just perfect fifth | 3⁄ 2 = 1.5 | ⓘ | 701.96 | +1.96 | ||||||

| 8 | G♯ or A♭ | 2 8⁄ 12 = | 1.58740... | ⓘ | 800 | Septimal minor sixth | 14⁄ 9 = 1.55555... | ⓘ | 764.92 | −35.08 |

| Undecimal minor sixth | 11⁄ 7 = 1.57142... | ⓘ | 782.49 | −17.51 | ||||||

| Pythagorean minor sixth | 128⁄ 81 = 1.58024... | ⓘ | 792.18 | −7.82 | ||||||

| Just minor sixth | 8⁄ 5 = 1.6 | ⓘ | 813.69 | +13.69 | ||||||

| Pythagorean augmented fifth | 6561⁄ 4096 = 1.60180... | ⓘ | 815.64 | +15.64 | ||||||

| 9 | A | 2 9⁄ 12 = | 1.68179... | ⓘ | 900 | Pythagorean diminished seventh | 32768⁄ 19683 = 1.66478... | ⓘ | 882.40 | −17.60 |

| Just major sixth | 5⁄ 3 = 1.66666... | ⓘ | 884.36 | −15.64 | ||||||

| Nineteenth subharmonic | 32⁄ 19 = 1.68421... | ⓘ | 902.49 | +2.49 | ||||||

| Pythagorean major sixth | 27⁄ 16 = 1.6875 | ⓘ | 905.87 | +5.87 | ||||||

| Septimal major sixth | 12⁄ 7 = 1.71428... | ⓘ | 933.13 | +33.13 | ||||||

| 10 | A♯ or B♭ | 2 10⁄ 12 = | 1.78179... | ⓘ | 1000 | Harmonic seventh | 7⁄ 4 = 1.75 | ⓘ | 968.83 | −31.17 |

| Pythagorean minor seventh | 16⁄ 9 = 1.77777... | ⓘ | 996.09 | −3.91 | ||||||

| Large minor seventh | 9⁄ 5 = 1.8 | ⓘ | 1017.60 | +17.60 | ||||||

| Pythagorean augmented sixth | 59049⁄ 32768 = 1.80203... | ⓘ | 1019.55 | +19.55 | ||||||

| 11 | B | 2 11⁄ 12 = | 1.88774... | ⓘ | 1100 | Tridecimal neutral seventh | 13⁄ 7 = 1.85714... | ⓘ | 1071.70 | −28.30 |

| Pythagorean diminished octave | 4096⁄ 2187 = 1.87288... | ⓘ | 1086.31 | −13.69 | ||||||

| Just major seventh | 15⁄ 8 = 1.875 | ⓘ | 1088.27 | −11.73 | ||||||

| Seventeenth subharmonic | 32⁄ 17 = 1.88235... | ⓘ | 1095.04 | −4.96 | ||||||

| Pythagorean major seventh | 243⁄ 128 = 1.89843... | ⓘ | 1109.78 | +9.78 | ||||||

| Septimal major seventh | 27⁄ 14 = 1.92857... | ⓘ | 1137.04 | +37.04 | ||||||

| 12 | C | 2 12⁄ 12 = 2 | 2 | ⓘ | 1200 | Octave | 2⁄ 1 = 2 | ⓘ | 1200.00 | 0 |

Commas

[edit]12-ET tempers out several commas, meaning that there are several fractions close to 1 /1 that are treated as 1 /1 by 12-ET due to its mapping of different fractions to the same equally-tempered interval. For example, 729/512 ( 36 /29) and 1024 /729 ( 210 /36) are each mapped to the tritone, so they are treated as nominally the same interval; therefore, their quotient, 531441/ 524288 ( 312 /219) is mapped to/treated as unison. This is the Pythagorean comma, and it is 12-ET's only 3-limit comma. However, as one increases the prime limit and includes more intervals, the number of commas increases. 12-ET's most important five-limit comma is 81/ 80 (34/ 24 × 51 ), which is known as the syntonic comma and is the factor between Pythagorean thirds and sixths and their just counterparts. 12-ET's other 5-limit commas include:

- Schisma: 32805/ 32768 = 38 × 51 /215 = (531441/ 524288 )1 × (81/ 80 )−1

- Diaschisma: 2048/ 2025 = 211/ 34 × 52 = (531441/ 524288 )−1 × (81/ 80 )2

- Lesser diesis: 128/ 125 = 27 /53 = (531441/ 524288 )−1 × (81/ 80 )3

- Greater diesis: 648/ 625 = 23 × 34 /54=(531441/ 524288 )−1 × (81/ 80 )4

One of the 7-limit commas that 12-ET tempers out is the septimal kleisma, which is equal to 225/ 224 , or 32×52 /25×71. 12-ET's other 7-limit commas include:

- Septimal semicomma: 126/ 125 = 21 × 32 × 71 /53 = (81/ 80 )1 × (225/ 224 )−1

- Archytas' comma: 64/ 63 = 26/ 32 × 71 = (531441/ 524288 )−1 × (81/ 80 )2 × (225/ 224 )1

- Septimal quarter tone: 36/ 35 = 22 × 32 /51 ×v71 = (531441/ 524288 )−1 × (81/80)3 × (225/ 224 )1

- Jubilisma: 50/ 49 = 21 × 52 /72 = (531441/ 524288 )−1 × (81/ 80 )2 × (225/ 224 )2

Scale diagram

[edit]

| Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B♭ major | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | G | A | 2 | C𝄫 major | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F𝄫 | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | 14 | |

| F major | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E | 1 | G𝄫 major | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | 13 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C major | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | 0 (no sharps or flats) | D𝄫 major | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | 12 | |

| G major | G | A | B | C | D | E | F♯ | 1 | A𝄫 major | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | 11 | |

| D major | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C♯ | 2 | E𝄫 major | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | 10 | |

| A major | A | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G♯ | 3 | B𝄫 major | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | 9 | |

| E major | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | D♯ | 4 | F♭ major | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | 8 | |

| B major | B | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | 5 | C♭ major | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | 7 | |

| F♯ major | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | 6 | G♭ major | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F | 6 | |

| C♯ major | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | 7 | D♭ major | D♭ | E♭ | F | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C | 5 | |

| G♯ major | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | 8 | A♭ major | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G | 4 | |

| D♯ major | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | 9 | E♭ major | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | D | 3 | |

| A♯ major | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | 10 | B♭ major | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | G | A | 2 | |

| E♯ major | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | 11 | F major | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E | 1 | |

| B♯ major | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | 12 | C major | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | 0 (no flats or sharps) | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F𝄪 major | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | 13 | G major | G | A | B | C | D | E | F♯ | 1 | |

| C𝄪 major | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B𝄪 | 14 | D major | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C♯ | 2 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C Dorian | C | D | E♭ | F | G | A | B♭ | 2 | D𝄫 Dorian | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F𝄫 | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | 14 | |

| G Dorian | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E | F | 1 | A𝄫 Dorian | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | 13 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D Dorian | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | 0 (no sharps or flats) | E𝄫 Dorian | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | 12 | |

| A Dorian | A | B | C | D | E | F♯ | G | 1 | B𝄫 Dorian | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | 11 | |

| E Dorian | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C♯ | D | 2 | F♭ Dorian | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | 10 | |

| B Dorian | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | 3 | C♭ Dorian | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | 9 | |

| F♯ Dorian | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | D♯ | E | 4 | G♭ Dorian | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | 8 | |

| C♯ Dorian | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B | 5 | D♭ Dorian | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | 7 | |

| G♯ Dorian | G♯ | A♯ | B | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | 6 | A♭ Dorian | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F | G♭ | 6 | |

| D♯ Dorian | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | 7 | E♭ Dorian | E♭ | F | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | 5 | |

| A♯ Dorian | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | 8 | B♭ Dorian | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | 4 | |

| E♯ Dorian | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | 9 | F Dorian | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | 3 | |

| B♯ Dorian | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | 10 | C Dorian | C | D | E♭ | F | G | A | B♭ | 2 | |

| F𝄪 Dorian | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | 11 | G Dorian | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E | F | 1 | |

| C𝄪 Dorian | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | 12 | D Dorian | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | 0 (no flats or sharps) | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G𝄪 Dorian | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | 13 | A Dorian | A | B | C | D | E | F♯ | G | 1 | |

| D𝄪 Dorian | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B𝄪 | C𝄪 | 14 | E Dorian | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C♯ | D | 2 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D Phrygian | D | E♭ | F | G | A | B♭ | C | 2 | E𝄫 Phrygian | E𝄫 | F𝄫 | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | 14 | |

| A Phrygian | A | B♭ | C | D | E | F | G | 1 | B𝄫 Phrygian | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | 13 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E Phrygian | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | 0 (no sharps or flats) | F♭ Phrygian | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | 12 | |

| B Phrygian | B | C | D | E | F♯ | G | A | 1 | C♭ Phrygian | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | 11 | |

| F♯ Phrygian | F♯ | G | A | B | C♯ | D | E | 2 | G♭ Phrygian | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | 10 | |

| C♯ Phrygian | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | 3 | D♭ Phrygian | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | 9 | |

| G♯ Phrygian | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | 4 | A♭ Phrygian | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | 8 | |

| D♯ Phrygian | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B | C♯ | 5 | E♭ Phrygian | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | 7 | |

| A♯ Phrygian | A♯ | B | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | 6 | B♭ Phrygian | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F | G♭ | A♭ | 6 | |

| E♯ Phrygian | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | 7 | F Phrygian | F | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | 5 | |

| B♯ Phrygian | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | 8 | C Phrygian | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | 4 | |

| F𝄪 Phrygian | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | 9 | G Phrygian | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | 3 | |

| C𝄪 Phrygian | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | 10 | D Phrygian | D | E♭ | F | G | A | B♭ | C | 2 | |

| G𝄪 Phrygian | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | 11 | A Phrygian | A | B♭ | C | D | E | F | G | 1 | |

| D𝄪 Phrygian | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | 12 | E Phrygian | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | 0 (no flats or sharps) | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A𝄪 Phrygian | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | 13 | B Phrygian | B | C | D | E | F♯ | G | A | 1 | |

| E𝄪 Phrygian | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B𝄪 | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | 14 | F♯ Phrygian | F♯ | G | A | B | C♯ | D | E | 2 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E♭ Lydian | E♭ | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | 2 | F𝄫 Lydian | F𝄫 | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | 14 | |

| B♭ Lydian | B♭ | C | D | E | F | G | A | 1 | C𝄫 Lydian | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | 13 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F Lydian | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | 0 (no sharps or flats) | G𝄫 Lydian | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | 12 | |

| C Lydian | C | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | 1 | D𝄫 Lydian | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | 11 | |

| G Lydian | G | A | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | 2 | A𝄫 Lydian | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | 10 | |

| D Lydian | D | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | 3 | E𝄫 Lydian | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | 9 | |

| A Lydian | A | B | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | 4 | B𝄫 Lydian | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | 8 | |

| E Lydian | E | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B | C♯ | D♯ | 5 | F♭ Lydian | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | 7 | |

| B Lydian | B | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | 6 | C♭ Lydian | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | 6 | |

| F♯ Lydian | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | 7 | G♭ Lydian | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | 5 | |

| C♯ Lydian | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | 8 | D♭ Lydian | D♭ | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | 4 | |

| G♯ Lydian | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | 9 | A♭ Lydian | A♭ | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | G | 3 | |

| D♯ Lydian | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | 10 | E♭ Lydian | E♭ | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | 2 | |

| A♯ Lydian | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | 11 | B♭ Lydian | B♭ | C | D | E | F | G | A | 1 | |

| E♯ Lydian | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | 12 | F Lydian | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | 0 (no flats or sharps) | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B♯ Lydian | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | 13 | C Lydian | C | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | 1 | |

| F𝄪 Lydian | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B𝄪 | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | 14 | G Lydian | G | A | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | 2 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F Mixolydian | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | 2 | G𝄫 Mixolydian | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F𝄫 | 14 | |

| C Mixolydian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B♭ | 1 | D𝄫 Mixolydian | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | 13 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G Mixolydian | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | 0 (no sharps or flats) | A𝄫 Mixolydian | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | 12 | |

| D Mixolydian | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C | 1 | E𝄫 Mixolydian | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | 11 | |

| A Mixolydian | A | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G | 2 | B𝄫 Mixolydian | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | 10 | |

| E Mixolydian | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | D | 3 | F♭ Mixolydian | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | 9 | |

| B Mixolydian | B | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | 4 | C♭ Mixolydian | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | 8 | |

| F♯ Mixolydian | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B | C♯ | D♯ | E | 5 | G♭ Mixolydian | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | 7 | |

| C♯ Mixolydian | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B | 6 | D♭ Mixolydian | D♭ | E♭ | F | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | 6 | |

| G♯ Mixolydian | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | 7 | A♭ Mixolydian | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G♭ | 5 | |

| D♯ Mixolydian | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | 8 | E♭ Mixolydian | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | 4 | |

| A♯ Mixolydian | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | 9 | B♭ Mixolydian | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | 3 | |

| E♯ Mixolydian | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | 10 | F Mixolydian | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | 2 | |

| B♯ Mixolydian | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | 11 | C Mixolydian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B♭ | 1 | |

| F𝄪 Mixolydian | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | 12 | G Mixolydian | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | 0 (no flats or sharps) | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C𝄪 Mixolydian | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | 13 | D Mixolydian | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C | 1 | ||

| G𝄪 Mixolydian | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B𝄪 | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | 14 | A Mixolydian | A | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G | 2 | ||

| Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G minor | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | 2 | A𝄫 minor | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F𝄫 | G𝄫 | 14 | |

| D minor | D | E | F | G | A | B♭ | C | 1 | E𝄫 minor | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | 13 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A minor | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | 0 (no sharps or flats) | B𝄫 minor | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | 12 | |

| E minor | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C | D | 1 | F♭ minor | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | 11 | |

| B minor | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G | A | 2 | C♭ minor | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | 10 | |

| F♯ minor | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | D | E | 3 | G♭ minor | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | 9 | |

| C♯ minor | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | 4 | D♭ minor | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | 8 | |

| G♯ minor | G♯ | A♯ | B | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | 5 | A♭ minor | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | 7 | |

| D♯ minor | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B | C♯ | 6 | E♭ minor | E♭ | F | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | 6 | |

| A♯ minor | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | 7 | B♭ minor | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G♭ | A♭ | 5 | |

| E♯ minor | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | 8 | F minor | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | 4 | |

| B♯ minor | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | 9 | C minor | C | D | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | 3 | |

| F𝄪 minor | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | 10 | G minor | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | 2 | |

| C𝄪 minor | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | 11 | D minor | D | E | F | G | A | B♭ | C | 1 | |

| G𝄪 minor | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | 12 | A minor | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | 0 (no flats or sharps) | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D𝄪 minor | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | 13 | E minor | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C | D | 1 | |

| A𝄪 minor | A𝄪 | B𝄪 | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | 14 | B minor | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G | A | 2 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Locrian | A | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | G | 2 | B𝄫 Locrian | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F𝄫 | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | 14 | |

| E Locrian | E | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | 1 | F♭ Locrian | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C𝄫 | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | 13 | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of flats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B Locrian | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | 0 (no sharps or flats) | C♭ Locrian | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | G𝄫 | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | 12 | |

| F♯ Locrian | F♯ | G | A | B | C | D | E | 1 | G♭ Locrian | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | D𝄫 | E𝄫 | F♭ | 11 | |

| C♯ Locrian | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | 2 | D♭ Locrian | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | A𝄫 | B𝄫 | C♭ | 10 | |

| G♯ Locrian | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | 3 | A♭ Locrian | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | E𝄫 | F♭ | G♭ | 9 | |

| D♯ Locrian | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | 4 | E♭ Locrian | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B𝄫 | C♭ | D♭ | 8 | |

| A♯ Locrian | A♯ | B | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | 5 | B♭ Locrian | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | 7 | |

| E♯ Locrian | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | B | C♯ | D♯ | 6 | F Locrian | F | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | C♭ | D♭ | E♭ | 6 | |

| B♯ Locrian | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ | 7 | C Locrian | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ | 5 | |

| F𝄪 Locrian | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | 8 | G Locrian | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | 4 | |

| C𝄪 Locrian | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | 9 | D Locrian | D | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | 3 | |

| G𝄪 Locrian | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | D♯ | E♯ | F𝄪 | 10 | A Locrian | A | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | F | G | 2 | |

| D𝄪 Locrian | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A♯ | B♯ | C𝄪 | 11 | E Locrian | E | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | 1 | |

| A𝄪 Locrian | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E♯ | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | 12 | B Locrian | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | 0 (no flats or sharps) | |

| Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | Key signature | Scale | Number of sharps | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E𝄪 Locrian | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | B♯ | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | 13 | F♯ Locrian | F♯ | G | A | B | C | D | E | 1 | |

| B𝄪 Locrian | B𝄪 | C𝄪 | D𝄪 | E𝄪 | F𝄪 | G𝄪 | A𝄪 | 14 | C♯ Locrian | C♯ | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | 2 | |

Similar tuning systems

[edit]Historically, multiple tuning systems have been used that can be seen as slight variations of 12-TEDO, with twelve notes per octave but with some variation among interval sizes so that the notes are not quite equally-spaced. One example of this a three-limit scale where equally-tempered perfect fifths of 700 cents are replaced with justly-intoned perfect fifths of 701.955 cents. Because the two intervals differ by less than 2 cents, or 1⁄600 of an octave, the two scales are very similar. In fact, the Chinese developed 3-limit just intonation at least a century before He Chengtian created the sequence of 12-TEDO.[38] Likewise, Pythagorean tuning, which was developed by ancient Greeks, was the predominant system in Europe until during the Renaissance, when Europeans realized that dissonant intervals such as 81⁄64[39] could be made more consonant by tempering them to simpler ratios like 5⁄4, resulting in Europe developing a series of meantone temperaments that slightly modified the interval sizes but could still be viewed as an approximate of 12-TEDO. Due to meantone temperaments' tendency to concentrate error onto one enharmonic perfect fifth, making it very dissonant, European music theorists, such as Andreas Werckmeister, Johann Philipp Kirnberger, Francesco Antonio Vallotti, and Thomas Young, created various well temperaments with the goal of dividing up the commas in order to reduce the dissonance of the worst-affected intervals. Werckmeister and Kirnberger were each dissatisfied with his first temperament and therefore created multiple temperaments, the latter temperaments more closely approximating equal temperament than the former temperaments. Likewise, Europe as a whole gradually transitioned from meantone and well temperaments to 12-TEDO, the system that it still uses today.

Subsets

[edit]While some types of music, such as serialism, use all twelve notes of 12-TEDO, most music only uses notes from a particular subset of 12-TEDO known as a scale. Many different types of scales exist.

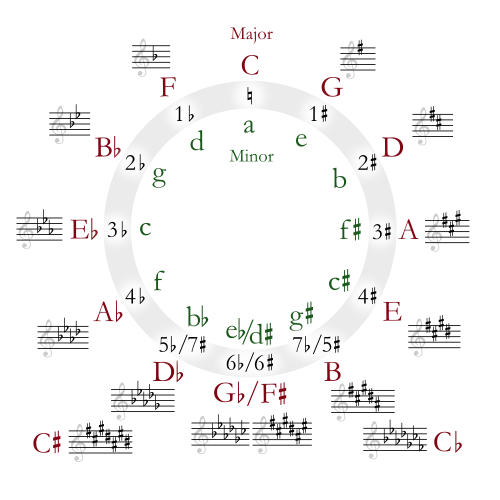

The most popular type of scale in 12-TEDO is meantone. Meantone refers to any scale where all of its notes are consecutive on the circle of fifths. Meantone scales of different sizes exist, and some meantone scales used include five-note meantone, seven-note meantone, and nine-note meantone. Meantone is present in the design of Western instruments. For example, the keys of a piano and its predecessors are structured so that the white keys form a seven-note meantone scale and the black keys form a five-note meantone scale. Another example is that guitars and other string instruments with at least five strings are typically tuned so that their open strings form a five-note meantone scale.

Other scales used in 12-TEDO include the ascending melodic minor scale, the harmonic minor, the harmonic major, the diminished scale, and the in scale.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Also known as twelve-tone equal temperament (12-TET), 12-tone equal division of the octave (12-TEDO), 12 equal division of 2/1 (12-ED2), 12 equal division of the octave (12-EDO); informally abbreviated to twelve equal or referred to as equal temperament without qualification in Western countries.

- ^ It is probably not an accident that as tuning in European music became increasingly close to 12ET, the style of the music changed so that the defects of 12ET appeared less evident, though it should be borne in mind that in actual performance these are often reduced by the tuning adaptations of the performers.[citation needed]

Citations

[edit]- ^ von Helmholtz & Ellis 1885, pp. 493–511.

- ^ a b Kuttner 1975, p. 163.

- ^ a b Kuttner 1975, p. 200.

- ^ Robinson 1980, p. vii: Chu-Tsaiyu the first formulator of the mathematics of "equal temperament" anywhere in the world

- ^ a b c Needham, Ling & Robinson 1962, p. 221.

- ^ Kwang-chih Chang, Pingfang Xu & Liancheng Lu 2005, p. 140.

- ^ Goodman, Howard L.; Lien, Y. Edmund (April 2009). "A Third Century AD Chinese System of Di-Flute Temperament: Matching Ancient Pitch-Standards and Confronting Modal Practice". The Galpin Society Journal. 62. Galpin Society: 7. JSTOR 20753625.

- ^ Barbour 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Hart 1998.

- ^ Needham & Ronan 1978, p. 385.

- ^ a b Cho 2010.

- ^ a b Lienhard 1997.

- ^ a b Christensen 2002, p. 205.

- ^ Barbour 2004, p. 7.

- ^ von Helmholtz & Ellis 1885, p. 258.

- ^ True 2018, pp. 61–74.

- ^ Galilei 1584, pp. 80–89.

- ^ Barbour 2004, p. 8.

- ^ de Gorzanis 1981.

- ^ "Spinacino 1507a: Thematic Index". Appalachian State University. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ Wilson 1997.

- ^ Jorgens 1986.

- ^ "Scintille de musica", (Brescia, 1533), p. 132

- ^ Cohen 1987, pp. 471–488.

- ^ Cho 2003, p. 223.

- ^ Cho 2003, p. 222.

- ^ Christensen 2002, p. 207.

- ^ Christensen 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Lindley, Mark. Lutes, Viols, Temperaments. ISBN 978-0-521-28883-5

- ^ Vm7 6214

- ^ Andreas Werckmeister (1707), Musicalische Paradoxal-Discourse

- ^ Di Veroli 2009, pp. 140, 142 and 256.

- ^ Moody 2003.

- ^ von Helmholtz & Ellis 1885, p. 548.

- ^ White, William Braid (1946) [1917]. Piano Tuning and Allied Arts (5th enlarged ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Tuners Supply Co. p. 68.

- ^ Barbour 2004, pp. 55–78.

- ^ Partch 1979, p. 134.

- ^ Needham, Ling & Robinson 1962, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 56.

Sources

[edit]- Barbour, James Murray (2004). Tuning and Temperament: A Historical Survey. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-43406-3.

- Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn (2003). Music in Theory and Practice. Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294261-3.

- Cho, Gene J. (2003). The Discovery of Musical Equal Temperament in China and Europe in the Sixteenth Century. E. Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-6941-9.

- Cho, Gene J. (2010). "The Significance of the Discovery of the Musical Equal Temperament in the Cultural History". Journal of Xinghai Conservatory of Music. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- Christensen, Thomas (2002). The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62371-1.

- Cohen, H. Floris (1987). "Simon Stevin's equal division of the octave". Annals of Science. 44 (5). Informa UK Limited: 471–488. doi:10.1080/00033798700200311. ISSN 0003-3790.

- de Gorzanis, G. (1981). Intabolatura di liuto: I-III. Intabolatura di liuto: I-III (in Italian). Minkoff. ISBN 978-2-8266-0721-2.

- Di Veroli, Claudio (2009). Unequal Temperaments: Theory, History and Practice (2nd ed.). Bray, Ireland: Bray Baroque.

- Galilei, Vincenzo (1584). Il Fronimo. Venice: Girolamo Scotto.

- Hart, Roger (1998), Quantifying Ritual: Political Cosmology, Courtly Music, and Precision Mathematics in Seventeenth-Century China, Departments of History and Asian Studies, University of Texas, Austin, archived from the original on 2012-03-05, retrieved 2012-03-20

- Jorgens, Elise Bickford (1986). English Song, 1600-1675: Facsimiles of Twenty-six Manuscripts and an Edition of the Texts. Garland. ISBN 9780824082314.

- Kuttner, Fritz A. (May 1975). "Prince Chu Tsai-Yü's Life and Work: A Re-Evaluation of His Contribution to Equal Temperament Theory" (PDF). Ethnomusicology. 19 (2): 163–206. doi:10.2307/850355. JSTOR 850355.

- Kwang-chih Chang; Pingfang Xu; Liancheng Lu (2005). "The eastern Zhou and the growth of regionalism". The Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective. Xu Pingfang, Shao Wangping, Zhang Zhongpei, Wang Renxiang. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09382-7.

- Lienhard, John H. (1997). "Equal Temperament". The Engines of Our Ingenuity. University of Houston. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- Moody, Richard (February 2003). "Early Equal Temperament, An Aural Perspective: Claude Montal 1836". Piano Technicians Journal. Kansas City.

- Needham, Joseph; Ling, Wang; Robinson, Kenneth G. (1962). Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 4 - Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05802-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Needham, Joseph; Ronan, Colin A. (1978). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 4 - Part 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Partch, Harry (1979). Genesis of a Music (2nd ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80106-X.

- Robinson, Kenneth (1980). A Critical Study of Chu Tsai-yü's Contribution to the Theory of Equal Temperament in Chinese Music. Volume 9 of Sinologica Coloniensia. Wiesbaden: Steiner. ISBN 978-3-515-02732-8.

- Sethares, William A. (2005). Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale (2nd ed.). London: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 1-85233-797-4.

- True, Timothy (2018). "The Battle Between Impeccable Intonation and Maximized Modulation". Musical Offerings. 9 (2): 61–74. doi:10.15385/jmo.2018.9.2.2.

- von Helmholtz, Hermann; Ellis, Alexander J. (1885). On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green.

- Wilson, John (1997). "Thirty preludes in all (24) keys for lute [DP 49]". The Diapason Press. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Duffin, Ross W. How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and Why You Should Care). W.W. Norton & Company, 2007.

- Jorgensen, Owen. Tuning. Michigan State University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-87013-290-3

- Khramov, Mykhaylo. "Approximation of 5-limit just intonation. Computer MIDI Modeling in Negative Systems of Equal Divisions of the Octave", Proceedings of the International Conference SIGMAP-2008[permanent dead link], 26–29 July 2008, Porto, pp. 181–184, ISBN 978-989-8111-60-9

- Surjodiningrat, W., Sudarjana, P.J., and Susanto, A. (1972) Tone measurements of outstanding Javanese gamelans in Jogjakarta and Surakarta, Gadjah Mada University Press, Jogjakarta 1972. Cited on https://web.archive.org/web/20050127000731/http://web.telia.com/~u57011259/pelog_main.htm. Retrieved May 19, 2006.

- Stewart, P. J. (2006) "From Galaxy to Galaxy: Music of the Spheres" [1]

- Sensations of Tone a foundational work on acoustics and the perception of sound by Hermann von Helmholtz. Especially Appendix XX: Additions by the Translator, pages 430–556, (pdf pages 451–577)]

External links

[edit]- Xenharmonic wiki on EDOs vs. Equal Temperaments

- Huygens-Fokker Foundation Centre for Microtonal Music

- A.Orlandini: Music Acoustics

- "Temperament" from A supplement to Mr. Chambers's cyclopædia (1753)

- Barbieri, Patrizio. Enharmonic instruments and music, 1470–1900 Archived 2009-02-15 at the Wayback Machine. (2008) Latina, Il Levante Libreria Editrice

- Fractal Microtonal Music, Jim Kukula.

- All existing 18th century quotes on J.S. Bach and temperament

- Dominic Eckersley: "Rosetta Revisited: Bach's Very Ordinary Temperament"

- Well Temperaments, based on the Werckmeister Definition

- FAVORED CARDINALITIES OF SCALES by PETER BUCH

12 equal temperament

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and characteristics

12 equal temperament (12-TET), also known as twelve-tone equal temperament, is a musical tuning system that divides each octave into 12 equal semitones, with each semitone corresponding to a frequency ratio of (approximately 1.05946).[4][5] This uniform division ensures that the interval between any two adjacent notes is identical throughout the scale, creating a consistent logarithmic spacing of pitches.[6] A key characteristic of 12-TET is its enablement of modulation across all 12 major and 12 minor keys without requiring retuning, as enharmonic equivalents (such as C♯ and D♭) are tuned to the same pitch.[7] This contrasts with unequal tuning systems like meantone temperament, which favor certain consonant intervals in specific keys but introduce discrepancies when shifting to distant keys.[8] In 12-TET, the equal steps support chromatic harmony by allowing smooth transitions between any notes, facilitating complex progressions and transpositions that are essential in modern composition.[9] 12-TET's advantages include its versatility for polyphonic music and ease of transposition, making it the standard tuning for fixed-pitch Western instruments such as the piano, which uses this system to play scales in all keys, and the guitar, with its 12 frets per octave tuned equally.[10] The resulting chromatic scale comprises the 12 pitches: C, C♯/D♭, D, D♯/E♭, E, F, F♯/G♭, G, G♯/A♭, A, A♯/B♭, and B, forming the foundation for the Western tonal system.[11] Unlike just intonation, which uses simple integer ratios for pure consonances in limited contexts, 12-TET approximates these intervals to prioritize overall key flexibility.[12]Interval structure and notation

In 12 equal temperament (12-TET), the fundamental interval is the semitone, which divides the octave into 12 equal parts, each measuring exactly 100 cents.[13] The cent is a logarithmic unit of pitch interval where the octave spans 1200 cents, making the semitone the smallest standardized step in this system.[14] Diatonic intervals, which form the basis of common scales and modes, are constructed by stacking whole steps (two semitones, or 200 cents) and half steps (one semitone, or 100 cents).[15] Standard interval names in 12-TET correspond to specific numbers of semitones from the unison (0 semitones), emphasizing their role in harmonic and melodic structures. The following table summarizes the principal simple intervals up to the octave:| Semitones | Interval Name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Minor second |

| 2 | Major second |

| 3 | Minor third |

| 4 | Major third |

| 5 | Perfect fourth |

| 6 | Tritone (augmented fourth or diminished fifth) |

| 7 | Perfect fifth |

| 8 | Minor sixth |

| 9 | Major sixth |

| 10 | Minor seventh |

| 11 | Major seventh |

| 12 | Octave (perfect octave) |

Historical development

Origins in China

The origins of 12 equal temperament trace back to ancient Chinese music theory, where the division of the octave into 12 pitches, known as the lü (律), emerged as a foundational concept by the 3rd century BCE. This system, described in texts such as the Guanzi, utilized 12 bamboo pipes of graduated lengths to generate a chromatic series of tones for ceremonial and court music, approximating semitone intervals through empirical adjustments rather than precise equality. These lü pipes served as standards for tuning instruments and were integral to cosmological theories linking music to harmony in the universe.[19] Archaeological evidence further supports the early recognition of a 12-tone chromatic scale in pre-Han artifacts, with significant findings from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (circa 433 BCE) revealing a set of 65 bronze bells spanning over three octaves and tuned to all 12 semitones within an octave, as confirmed by modern acoustic analysis and inscriptions detailing pitch relationships. Recent studies, including digital recreations of these bells, indicate that ancient Chinese metallurgists achieved near-equal divisions through iterative casting techniques, predating mathematical formalization and demonstrating practical implementation in ritual ensembles during the Warring States period. Such discoveries highlight the chromatic framework's role in elite musical practices, with similar bell sets from the early Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) continuing these traditions.[20] A pivotal advancement occurred in the Ming dynasty with Prince Zhu Zaiyu (1536–1611), who in 1584 published the first exact mathematical formulation of 12-tone equal temperament in his treatise New Theory of Musical Tuning (Lüxue xinshuo), predating European adoption by over a century. Zhu employed a geometric progression—effectively the geometric mean of frequency ratios—to divide the octave into 12 equal semitones, calculating pipe lengths with high precision (e.g., deriving the semitone ratio as the 12th root of 2) and constructing a set of 36 bamboo pipes across three octaves to demonstrate the system. This innovation resolved inconsistencies in traditional lü tuning, which had accumulated errors from cyclic fifths, and was motivated by Zhu's studies of the guqin zither, where he sought consistent intonation across transpositions.[21] In cultural context, the 12-lü framework underpinned court music and instruments like the guqin, where players approximated semitones via string bends and node positions, while bamboo tubes provided portable standards for ensemble tuning in imperial rituals. Zhu's equal temperament, though theoretically advanced, saw limited immediate adoption due to entrenched just intonation practices but influenced later Chinese musicology and instrument design.[22]Development in Europe

In medieval Europe, musical tuning systems approximated the structure of what would later become 12 equal temperament through Pythagorean tuning, which divided the octave into intervals based primarily on pure fifths (3:2 ratio, approximately 702 cents) and produced a diatonic semitone of about 90 cents.[23] This system, inherited from ancient Greek traditions and widely used in Gregorian chant and early polyphony, allowed for consonant fifths and fourths but resulted in dissonant thirds and limited modulation due to the Pythagorean comma (about 23.5 cents), making enharmonic equivalents unequal.[24] By the late 15th century, as polyphonic music increasingly emphasized tertian harmonies, organ builders and theorists transitioned to meantone temperaments, which tempered the fifth slightly narrower (to around 696.6 cents in quarter-comma meantone) to achieve purer major thirds (5:4 ratio, 386 cents).[25] This innovation, first documented by Pietro Aaron in 1523, facilitated better chordal music in common keys but still featured unequal semitones—a small chromatic one of about 76 cents and a larger diatonic one of 117 cents—restricting full chromatic usage.[26] The mathematical foundation for true 12 equal temperament emerged in the late 16th century with Dutch mathematician Simon Stevin, who in his 1585 treatise Van de Spiegheling der Singconst described dividing the octave into 12 equal parts using logarithmic principles, yielding a semitone ratio of the 12th root of 2 (approximately 100 cents).[27] Stevin's work, though unpublished until the 19th century, provided the first precise European formulation of equal division, independent of practical instrument constraints and contrasting with earlier approximations that prioritized just intervals over uniformity.[28] During the Baroque era, equal temperament gained practical adoption among composers and instrument makers, enabling exploration of all 24 major and minor keys without retuning. Johann Sebastian Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier (1722) exemplified this shift, demonstrating preludes and fugues in every key on a keyboard tuned to a well-tempered system—likely close to equal temperament—that allowed seamless modulation and chromatic passages, marking a pivotal step toward its dominance in Western music.[29] By the late 18th century, equal temperament had become standard in France and Germany for keyboard instruments, with full adoption in England by the early 19th century as pianos proliferated.[29] Historical tuning systems approximated the equal semitone unevenly, as shown in the table below for representative small semitones (in cents, where 1200 cents = one octave):| System | Small Semitone (cents) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pythagorean | 90 | Diatonic limma (256:243 ratio); used in medieval monody.[23] |

| Quarter-Comma Meantone | 76 | Chromatic semitone; common in 16th-17th century organs for pure thirds.[26] |

| 12 Equal Temperament | 100 | Uniform across all; enables full chromaticism.[30] |

Mathematical principles

Frequency ratios and calculations

In 12 equal temperament (12-TET), the frequency of a pitch is calculated relative to a reference frequency using the formula , where is the frequency of the reference pitch (typically A4), and is the number of semitones above or below the reference (positive for ascending, negative for descending).[33] This exponential relationship ensures that each semitone multiplies the previous frequency by the constant twelfth root of 2, approximately 1.05946, dividing the octave (a 2:1 frequency ratio) into 12 equal logarithmic steps.[34] For example, to find the frequency of C4 assuming A4 = 440 Hz, note that C4 is 9 semitones below A4 (). Substituting into the formula gives Hz.[33] This calculation exemplifies how 12-TET pitches are derived systematically from the reference, enabling consistent transposition across the chromatic scale. The reference pitch for A4 has evolved through standardization efforts to facilitate international consistency in performance and instrument manufacturing. In 1859, France established A=435 Hz as a legal standard (diapason normal) to reconcile varying regional pitches, which had risen from around A=422 Hz in the 18th century to as high as A=450 Hz in some 19th-century contexts due to larger concert halls and brighter instrument timbres.[35] By 1939, an international conference in London recommended A=440 Hz, balancing orchestral preferences and electronic broadcasting needs, a standard reaffirmed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO 16) in 1955 and 1975.[35] In digital synthesis, 12-TET implementations can incorporate microtonal deviations for expressive tuning beyond strict equal temperament, particularly through post-2020 advancements in MIDI protocols. MIDI 2.0, officially released in 2020 with detailed specifications updated through 2023, introduces per-note pitch bend messages at 32-bit resolution, allowing individual notes to deviate from 12-TET intervals without affecting polyphony, thus supporting microtonal scales in software synthesizers and hardware.[36] This extends earlier MIDI Tuning Standard (MTS) approaches by enabling precise, real-time tuning adjustments in digital audio workstations.[37]Logarithmic basis and equal division

The octave in 12 equal temperament is defined by a frequency ratio of 2:1, representing the perceptual interval between a note and its double in frequency.[38] Human pitch perception follows a logarithmic scale, where intervals are proportional to the logarithm of frequency ratios rather than linear differences in frequency.[13] This logarithmic basis aligns with psychoacoustic models, as the just noticeable difference in pitch corresponds to a small percentage change in frequency, approximately 0.4% or 5 cents near middle frequencies.[13] To quantify intervals on this scale, the unit of cents is used, where one octave equals 1200 cents, introduced by mathematician Alexander J. Ellis in 1880 as a logarithmic measure.[8] The cent value of an interval with frequency ratio is given by allowing additive arithmetic for musical intervals despite their multiplicative frequency nature. In 12 equal temperament, the octave is divided into 12 equal steps, each a semitone with ratio , corresponding to exactly 100 cents per semitone.[38] This derivation follows from octave, or cents, ensuring uniform spacing in the logarithmic domain.[8] The choice of 12 divisions arises from its close approximation to the circle of fifths in just intonation, where seven perfect fifths (each ratio 3:2) span nearly four octaves, but extending to 12 fifths better closes the chromatic scale.[39] Mathematically, this stems from the continued fraction approximation of by the rational , implying modulo the octave, with an error of the Pythagorean comma (approximately 23.46 cents).[39] In 12 equal temperament, each fifth is set to exactly 700 cents (seven semitones), so 12 such fifths total 8400 cents, precisely seven octaves (7 × 1200 cents), achieving exact closure.[40] This requires tempering each just fifth (701.955 cents) down by about 1.955 cents, distributing the comma evenly to enable modulation through all keys without cumulative error.[40]Relation to just intonation

Approximations of consonant intervals

12 equal temperament (12-TET) approximates various consonant intervals from just intonation, where intervals are defined by simple integer frequency ratios, by dividing the octave into 12 equal semitones of 100 cents each. These approximations vary in accuracy depending on the prime limit of the just intervals considered, with lower limits (using smaller primes like 2 and 3) generally yielding closer matches to 12-TET than higher limits (introducing primes like 7, 11, or 17). The deviations, measured in cents, highlight how 12-TET tempers intervals to enable modulation across all keys while introducing small dissonances in pure consonant approximations. In 3-limit just intonation, which uses only the primes 2 and 3 (Pythagorean tuning), the perfect fifth (3:2, 701.96 cents) is approximated by 7 semitones (700 cents), resulting in a deviation of -1.96 cents (12-TET slightly flat). The perfect fourth (4:3, 498.04 cents) aligns with 5 semitones (500 cents), deviating by +1.96 cents (slightly sharp). However, the major third (81:64, 407.82 cents) is approximated by 4 semitones (400 cents), with a deviation of -7.82 cents (flat), which can sound relatively tense compared to narrower just versions. Expanding to 5-limit just intonation, incorporating the prime 5, yields better approximations for triadic intervals central to Western harmony. The major third (5:4, 386.31 cents) is close to 4 semitones (400 cents), deviating by +13.69 cents (sharp). The minor third (6:5, 315.64 cents) approximates 3 semitones (300 cents), with a -15.64 cents deviation (flat). The perfect fifth remains nearly identical at -1.96 cents, while the major sixth (5:3, 884.36 cents) deviates +15.64 cents from 9 semitones (900 cents, sharp). For 7-limit just intonation, introducing the prime 7 adds septimal intervals like the harmonic seventh (7:4, 968.83 cents), which 12-TET approximates with 10 semitones (1000 cents), resulting in a -31.17 cents deviation (flat). Other 7-limit intervals, such as the supermajor second (8:7, 231.17 cents), deviate significantly from 2 semitones (200 cents) by +31.17 cents (sharp). Higher limits like 11- and 13-limit introduce further consonant possibilities, while 17- and 19-limit offer exotic small intervals like the septendecimal comma (17:16, 104.96 cents) approximate the semitone (100 cents) with a +4.96 cents deviation (sharp), and the undecimal minor third (19:16, 297.46 cents) is close to 3 semitones (300 cents), -2.54 cents (flat). The following table summarizes key approximations, focusing on representative consonant intervals by limit:| Prime Limit | Just Ratio | Just Cents | 12-TET Semitones | 12-TET Cents | Error (Cents) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 3:2 (fifth) | 701.96 | 7 | 700 | -1.96 |

| 3 | 81:64 (major third) | 407.82 | 4 | 400 | -7.82 |

| 5 | 5:4 (major third) | 386.31 | 4 | 400 | +13.69 |

| 5 | 6:5 (minor third) | 315.64 | 3 | 300 | -15.64 |

| 7 | 7:4 (harmonic seventh) | 968.83 | 10 | 1000 | -31.17 |

| 17 | 17:16 (septendecimal semitone) | 104.96 | 1 | 100 | +4.96 |

Tempering and comma resolutions

In 12 equal temperament (12-TET), tempering involves systematically adjusting intervals from their just intonation ratios to distribute discrepancies evenly across the octave, thereby resolving small intervals known as commas that would otherwise prevent the closure of the circle of fifths. A key example is the syntonic comma, with a ratio of and a size of approximately 21.506 cents, which arises as the difference between the Pythagorean major third () and the just major third (). This comma is tempered out in 12-TET by narrowing each perfect fifth from its just ratio of (approximately 701.955 cents) to exactly 700 cents, such that four such tempered fifths yield a major third of 400 cents, effectively eliminating the syntonic comma across key modulations.[41][42] The Pythagorean comma, defined by the ratio and measuring about 23.46 cents, represents the primary discrepancy in pure fifths: twelve just fifths exceed seven octaves by this amount, failing to close the chromatic circle. 12-TET resolves this by dividing the octave into twelve equal semitones of 100 cents each, making twelve tempered fifths (7 × 1200 = 8400 cents) exactly equivalent to seven octaves without remainder, thus tempering out the Pythagorean comma entirely and enabling seamless progression through all twelve keys.[43][41] Other small intervals, such as the schisma (ratio , approximately 1.954 cents), are also effectively tempered out in 12-TET, as the system's equal division approximates the tempering of this comma to near-unison across the scale. This occurs because the 1.955-cent flattening of each fifth aligns closely with one-twelfth of the Pythagorean comma, which is nearly identical to the schisma, distributing the adjustment evenly rather than concentrating it in specific "wolf" intervals as in unequal temperaments. As a result, 12-TET achieves enharmonic equivalence, where notes like F♯ and G♭ occupy the identical pitch class, facilitating fluid chromaticism and modulation without tuning inconsistencies.[42][44][45]Scales and modes

Major and minor scales

In 12 equal temperament, the major scale, also known as the Ionian mode, is constructed using the step pattern of whole-whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half, where a whole step spans two semitones and a half step spans one semitone. This results in seven distinct pitches within an octave, with cumulative semitone intervals from the tonic of 0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 12. For instance, the C major scale comprises the notes C (tonic), D (supertonic), E (mediant), F (subdominant), G (dominant), A (submediant), and B (leading tone), returning to C.[46][4][47] Key intervals in the major scale include the major second (2 semitones), major third (4 semitones), perfect fourth (5 semitones), perfect fifth (7 semitones), major sixth (9 semitones), and major seventh (11 semitones), providing the characteristic bright and stable sound. These scale degrees serve functional roles in harmony, with the tonic establishing the key center, the dominant creating tension resolved back to the tonic, and the leading tone (major seventh) pulling strongly toward resolution.[48] The natural minor scale, or Aeolian mode, follows the pattern whole-half-whole-whole-half-whole-whole, yielding cumulative semitone intervals of 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, and 12 from the tonic. An example is the A minor scale: A (tonic), B (supertonic), C (mediant), D (subdominant), E (dominant), F (submediant), G (subtonic), and A.[49] This scale features a minor third (3 semitones), minor sixth (8 semitones), and minor seventh (10 semitones), contributing to its melancholic quality, while sharing the same key signature as its relative major (e.g., A minor and C major both use no sharps or flats).[47] To construct major and minor scales in other keys, accidentals (sharps or flats) are applied according to key signatures, which are determined by the circle of fifths in 12 equal temperament. Progressing clockwise adds one sharp per fifth (e.g., G major has one sharp, F♯), while counterclockwise adds one flat (e.g., F major has one flat, B♭); this system enables smooth modulation across all 12 major and 12 minor keys without retuning.[50]Modal variants

In 12 equal temperament (12-TET), the seven diatonic modes are derived from the major scale by rotating the starting point, creating variations in the sequence of whole steps (W, two semitones) and half steps (H, one semitone) while maintaining the same set of pitches within an octave.[51] These modes—Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian—provide distinct tonal flavors through their interval patterns, all fitting seamlessly into the 12 semitone framework.[52] The Ionian mode corresponds to the major scale, while the Aeolian mode aligns with the natural minor scale.[53] The interval patterns for each mode, starting from the tonic, are as follows:| Mode | Pattern |

|---|---|

| Ionian | W-W-H-W-W-W-H |

| Dorian | W-H-W-W-W-H-W |

| Phrygian | H-W-W-W-H-W-W |

| Lydian | W-W-W-H-W-W-H |

| Mixolydian | W-W-H-W-W-H-W |

| Aeolian | W-H-W-W-H-W-W |

| Locrian | H-W-W-H-W-W-W |

![{\textstyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f276a910a28604e3b8afd8ba62a4678a37193480)

![{\displaystyle \left({\sqrt[{12}]{2}}\right)^{12}=2}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1f0e94dc870dfc2af0eb35a7b362eb3776054719)

![{\displaystyle \left({\sqrt[{12}]{2}}\right)^{84}=2^{7}=128}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/efc85da07cabc4f33cc3fc965e9ef6e74361e7c7)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2}}=2^{\frac {1}{12}}\approx 1.059463}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/232c2beab28b1c46c328080d982595d9ef196e08)

![{\displaystyle P_{n}=P_{a}\left({\sqrt[{12}]{2}}\right)^{(n-a)}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3381e111c79f7e16a073bbe05c6cabeaba2ff79a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{alignedat}{3}P_{40}&=440\left({\sqrt[{12}]{2}}\right)^{(40-49)}&&\approx 261.626\ \mathrm {Hz} \\P_{46}&=440\left({\sqrt[{12}]{2}}\right)^{(46-49)}&&\approx 369.994\ \mathrm {Hz} \end{alignedat}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9b2cc77efb874655e7633d236cfd2c9f7e5b8229)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bc835f27425fb3140e1f75a5faa35b1e8b9efc35)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{6}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2fd2e90711da1208f1bf08c8992ab44739cb9c57)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{4}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9aa163183b2c3828db27e22253d454a643a4c936)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9ca071ab504481c2bb76081aacb03f5519930710)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{32}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9744b1d14b93f31471a1ad0e7176cbd2e42f1a9)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{128}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7fe1257282e06f592d5b60e9ce503586594b865c)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{4}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5eb5da5142ec773ea1ba79813278a00c8d9ee202)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{4}]{8}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/675096532680297bc0b8e3ef793ed8b9271f628e)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{6}]{32}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e75f5ed7285d717db47b68736ff2e37df9f71737)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2048}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/744decb84a19d221e7ce8df0ec3d315384fdd5ef)