Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

2004 enlargement of the European Union

View on Wikipedia

| History of the European Union |

|---|

|

|

|

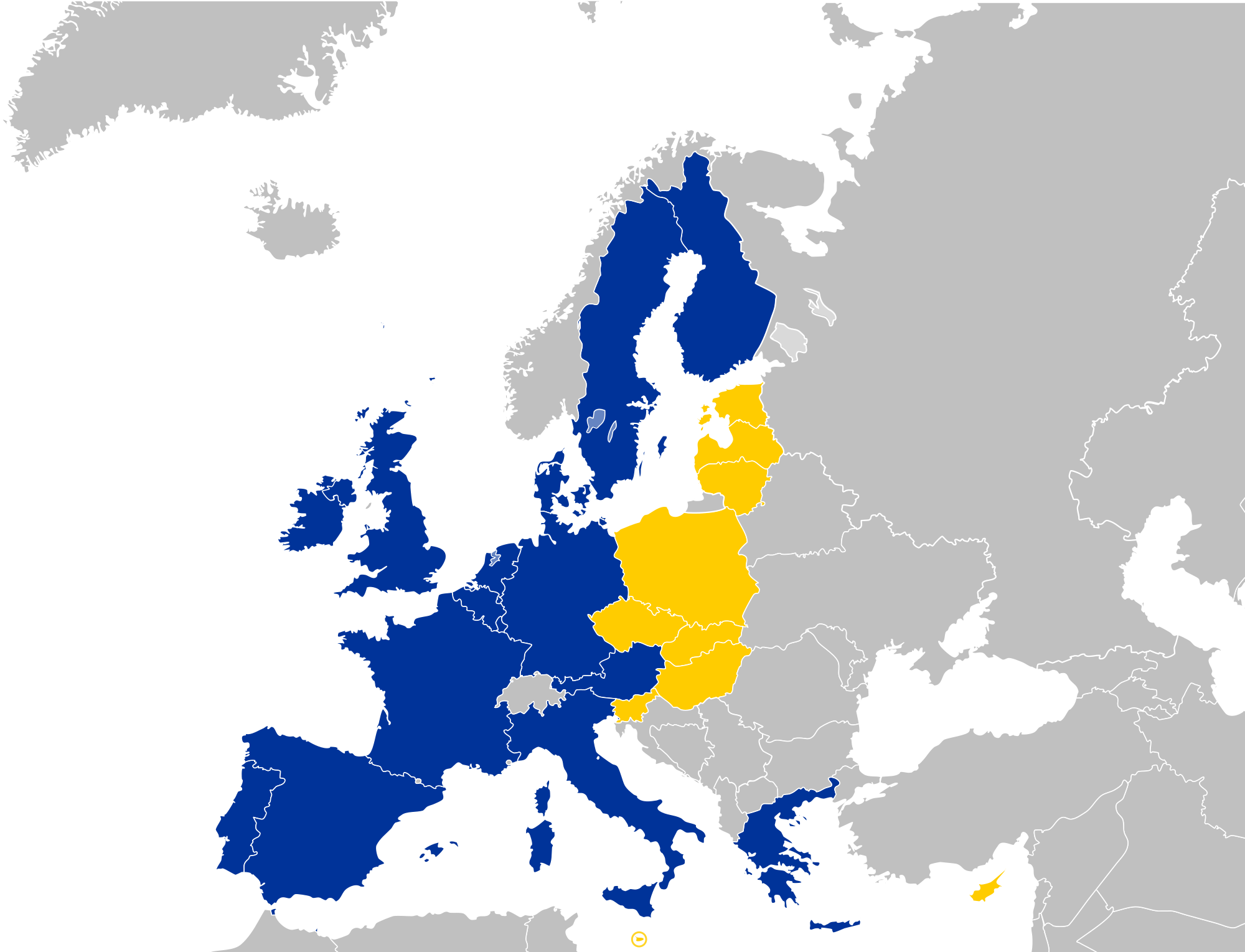

The largest enlargement of the European Union (EU), in terms of number of states and population, took place on 1 May 2004.

The simultaneous accessions concerned the following countries (sometimes referred to as the "A10" countries[1][2]): Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Seven of these were part of the former Eastern Bloc (of which three were from the former Soviet Union and four were and still are member states of the Central European alliance Visegrád Group). Slovenia was a non-aligned country prior to independence, and it was one of the former republics of Yugoslavia (together sometimes referred to as the "A8" countries), and the remaining two were Mediterranean island countries, both member states of the Commonwealth of Nations.

Part of the same wave of enlargement was the accession of Bulgaria and Romania in 2007, who were unable to join in 2004, but, according to the European Commission, constitute part of the fifth enlargement.

History

[edit]| Referendum results | |

|---|---|

77.3 / 100

| |

66.8 / 100

| |

83.8 / 100

| |

67.5 / 100

| |

91.1 / 100

| |

53.6 / 100

| |

77.6 / 100

| |

93.7 / 100

| |

89.6 / 100

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2011) |

Background

[edit]With the end of World War II in May 1945, Europe found itself divided between a capitalist Western Bloc and a communist Eastern Bloc, as well as Third World neutral countries. The European Economic Community (EEC) was created in 1957 between six countries within the Western Bloc and later expanded to twelve countries across Europe. European communist countries had a looser economic grouping with the USSR known as Comecon. To the south there was a non-aligned communist federated country – Yugoslavia.

Between 1989 and 1991, the Cold War between the two superpowers was coming to an end, with the USSR's influence over communist Europe collapsing. As the communist states began their transition to free market democracies, aligning to Euro-Atlantic integration, the question of enlargement into the continent was thrust onto the EEC's agenda.

Negotiations

[edit]The Phare strategy was launched soon after to adapt more the structure of the Central and Eastern European countries (Pays d'Europe Centrale et Orientale (PECO)) to the European Economic Community. One of the major tools of this strategy was the Regional Quality Assurance Program (Programme Régional d'Assurance Qualité (PRAQ)) which started in 1993 to help the PECO States implement the New Approach in their economy.[3]

The Acquis Communautaire contained 3,000 directives and some 100,000 pages in the Official Journal of the European Union to be transposed. It demanded a lot of administrative work and immense economic change, and raised major cultural problems – e.g. new legal concepts and language consistency problems.

Accession

[edit]Malta held a non-binding referendum on 8 March 2003; the narrow Yes vote prompted a snap election on 12 April 2003 fought on the same question and after which the pro-EU Nationalist Party retained its majority and declared a mandate for accession.

Poland held a referendum on 7 and 8 June 2003: [1] voting Yes by a wide margin of about 77.5% with a turnout of around 59%.

The Treaty of Accession 2003 was signed on 16 April 2003, at the Stoa of Attalus in Athens, Greece, between the then-EU members and the ten acceding countries. The text also amended the main EU treaties, including the Qualified Majority Voting of the Council of the European Union. The treaty was ratified on time and entered into force on 1 May 2004 amid ceremonies around Europe.

European leaders met in Dublin for fireworks and a flag-raising ceremony at Áras an Uachtaráin, the Irish presidential residence. At the same time, citizens across Ireland enjoyed a nationwide celebration styled as the Day of Welcomes. President Romano Prodi took part in celebrations on the Italian-Slovenian border at the divided town of Gorizia/Nova Gorica; at the German-Polish border, the EU flag was raised and Ode to Joy was sung; and there was a laser show in Malta, among the various other celebrations.[4]

Limerick, Ireland's third largest city, hosted Slovenia as one of ten cities and towns to individually welcome the ten accession countries. The then Slovenian Prime Minister Anton Rop was Guest Speaker at a business luncheon hosted by Limerick Chamber.

Progress

[edit]This page or section uses colour as the only way to convey important information. (July 2023) |

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2014) |

Event |

Czech Republic | Slovakia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU Association Agreement 1 negotiations start | 1990 | 1990 | |||||||||||||||

| EU Association Agreement signature | 4 October 1993 | 4 October 1993 | |||||||||||||||

| EU Association Agreement entry into force | 1 February 1995 | 1 February 1995 | |||||||||||||||

| Membership application submitted | 17 January 1996 | 27 June 1995 | |||||||||||||||

| Council asks Commission for opinion | 29 June 1996 | 17 July 1995 | |||||||||||||||

| Commission presents legislative questionnaire to applicant | Mar 1996 | Mar 1996 | |||||||||||||||

| Applicant responds to questionnaire | Jun 1997 | Jun 1997 | |||||||||||||||

| Commission prepares its opinion (and subsequent reports) | 15 July 1997 | 1997, 1998, 1999 | |||||||||||||||

| Commission recommends granting of candidate status | 15 July 1997 | 15 July 1997 | |||||||||||||||

| European Council grants candidate status to Applicant[5] | 12 December 1997 | 12 December 1997 | |||||||||||||||

| Commission recommends starting of negotiations | 15 July 1997 | 13 October 1999 | |||||||||||||||

| European Council sets negotiations start date | 12 December 1997[6] | 10 December 1999 | |||||||||||||||

| Membership negotiations start | 31 March 1998 | 15 February 2000 | |||||||||||||||

| Membership negotiations end | 13 December 2002 | 13 December 2002 | |||||||||||||||

| Accession Treaty signature | 16 April 2003 | 16 April 2003 | |||||||||||||||

| EU joining date | 1 May 2004 | 1 May 2004 | |||||||||||||||

| Acquis chapter | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Free Movement of Goods | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Freedom of Movement for Workers | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Right of Establishment & Freedom to provide Services | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Free Movement of Capital | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Public Procurement | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Company Law | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Intellectual Property Law | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 8. Competition Policy | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 9. Financial Services | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 10. Information Society & Media | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 11. Agriculture & Rural Development | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 12. Food safety, Veterinary & Phytosanitary Policy | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 13. Fisheries | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 14. Transport Policy | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 15. Energy | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 16. Taxation | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 17. Economic & Monetary Policy | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 18. Statistics | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 19. Social Policy & Employment | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 20. Enterprise & Industrial Policy | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 21. Trans-European Networks | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 22. Regional Policy & Coordination of Structural Instruments | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 23. Judiciary & Fundamental Rights | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 24. Justice, Freedom & Security | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 25. Science & Research | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 26. Education & Culture | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 27. Environment | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 28. Consumer & Health Protection | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 29. Customs Union | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 30. External Relations | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 31. Foreign, Security & Defence Policy | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 32. Financial Control | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 33. Financial & Budgetary Provisions | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 34. Institutions | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 35. Other Issues | x | x | |||||||||||||||

1 EU Association Agreement type: Europe Agreement for the states of the Fifth Enlargement.

| Situation of policy area at the start of membership negotiations according to the 1997 Opinions and 1999 Reports. | ||

|

s – screening of the chapter |

generally already applies the acquis

no major difficulties expected

further efforts needed

non-acquis chapter – nothing to adopt

|

considerable efforts needed

very hard to adopt

situation totally incompatible with EU acquis

|

Free movement issues

[edit]

As of May 2011, there are no longer any special restrictions on the free movement of citizens of these new member states.

With their original accession to the EU, free movement of people between all 25 states would naturally have applied. However, due to concerns of mass migration from the new members to the old EU-15, some transitional restrictions were put in place. Mobility within the EU-15 (plus Cyprus) and within the new states (minus Cyprus) functioned as normal (although the new states had the right to impose restrictions on travel between them). Between the old and new states, transitional restrictions up to 1 May 2011 could be put in place, and EU workers still had a preferential right over non-EU workers in looking for jobs even if restrictions were placed upon their country. No restrictions were placed on Cyprus or Malta. The following restrictions were put in place by each country;[7]

- Austria and Germany: Restriction on free movement and to provide certain services. Work permits still needed for all countries. In Austria, to be employed the worker needs to have been employed for more than a year in his home country prior to accession. Germany had bilateral quotas which remained in force.

- Cyprus: No restrictions.

- Malta: No restrictions on its workers, but does have the right to migration into the country.

- Netherlands: Initially against restrictions, but tightened up its policies in early 2004 and said it would tighten its policies if more than 22,000 workers arrived per year.

- Finland: 2 years of transitional arrangements where a work permit would be granted only where a Finnish national cannot be found for the job. Does not apply to students, part-time workers, entrepreneurs, people living in Finland for non-work purposes, people who were already living in Finland for a year or people who would be entitled to work anyway if they were from a third country.

- Denmark: Two years where only full-time workers can get a work permit, if they had a residence permit. Workers did not get welfare but restrictions only apply to wage earners (all the EU-10 citizens can set up a business).

- France: Five years of restrictions depending on sector and region. Students, researchers, self-employed and service providers were exempt from the restrictions.

- Spain: Two years.

- Portugal: Two years, annual limit of 6,500.

- Sweden: No restrictions.

- Czech Republic and Slovakia: No restrictions.

- Poland: Reciprocal limits, only British and Irish citizens had free access. Countries with looser or tighter limits face similar limits in Poland.

- Belgium, Greece and Luxembourg: Two years.

- United Kingdom: Welfare restrictions only, registration needed.

- Ireland: No restrictions.

- Hungary: Reciprocal limits for seven years.

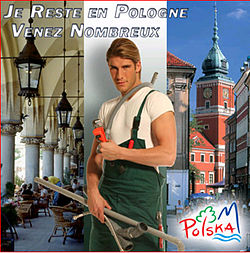

Despite the fears, migration within the EU concerns less than 2% of the population.[8] However, the migration did cause controversy in those countries which saw a noticeable influx, creating the image of a "Polish Plumber" in the EU, caricaturing the cheap manual labour from A8 countries making an imprint on the rest of the EU. The extent to which E8 immigration generated a lasting public backlash has been debated. Ten years after the enlargement, a study showed that increases in E8 migrants in Western Europe over the last ten years had been accompanied by a more widespread acknowledgement of the economic benefits of immigration.[9] Following the 2007 enlargement, most countries placed restrictions on the new states, including the most open in 2004 (Ireland and the United Kingdom) with only Sweden, Finland and the 2004 members (minus Malta and Hungary).[10] But by April 2008, these restrictions on the eight members had been dropped by all members except Germany and Austria.[11]

Remaining areas of inclusion

[edit]Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia became members on 1 May 2004, but some areas of cooperation in the European Union will apply to some of the EU member states at a later date. These are:

- Schengen Area (see Enlargement of the Schengen Area; Cyprus is still not a member of the Schengen Area)

- Eurozone (see Enlargement of the eurozone; Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland are still not members of the Eurozone)

New member states

[edit]Cyprus

[edit]

Since 1974 Cyprus has been divided between the Greek south (the Republic of Cyprus) and the northern areas under Turkish military occupation (the self-proclaimed Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus). The Republic of Cyprus is recognised as the sole legitimate government by every UN (and EU) member state except Turkey, while the northern occupied area is recognised only by Turkey.

Cyprus began talks to join the EU, which provided impetus to solve the dispute. With the agreement of the Annan Plan for Cyprus, it was hoped that the two communities would join the EU together as a single United Cyprus Republic. Turkish Cypriots supported the plan. However, in a referendum on 24 April 2004 the Greek Cypriots rejected the plan. Thus, a week later, the Republic of Cyprus joined the EU with political issues unresolved. Legally, as the northern republic is not recognised by the EU, the entire island excluding the British overseas territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia is a member of the EU as part of the Republic of Cyprus, though the de facto situation is that the Government is unable to extend its controls into the occupied areas.

Efforts to reunite the island continue as of 2022. European Union membership forced the country to suspend its membership in the Non-Aligned Movement with Government of Cyprus insisting on maintaining close ties with the NAM.[12]

Poland

[edit]

Accession of Poland to the European Union took place in May 2004. Poland had been negotiating with the EU since 1989.

With the fall of communism in 1989/1990 in Poland, Poland embarked on a series of reforms and changes in foreign policy, intending to join the EU and NATO. On 19 September 1989 Poland signed the agreement for trade and trade co-operation with the (then) European Community (EC). Polish intention to join the EU was expressed by Polish Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki in his speech in the European Parliament in February 1990 and in June 1991 by Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Krzysztof Skubiszewski in Sejm (Polish Parliament).

On 19 May 1990 Poland started a procedure to begin negotiations for an association agreement and the negotiations officially began in December 1990. About a year later, on 16 December 1991 the European Union Association Agreement was signed by Poland. The Agreement came into force on 1 February 1994 (its III part on the mutual trade relations came into force earlier on 1 March 1992).

As a result of diplomatic interventions by the central European states of the Visegrád Group, the European Council decided at its Copenhagen summit in June 1993 that: "the associate member states from Central and Eastern Europe, if they so wish, will become members of the EU. To achieve this, however, they must fulfil the appropriate conditions." Those conditions (known as the Copenhagen criteria, or simply, membership criteria) were:

- That candidate countries achieve stable institutions that guarantee democracy, legality, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities.

- That candidate countries have a working market economy, capable of competing effectively on EU markets.

- That candidate countries are capable of accepting all the membership responsibilities, political, economic and monetary.

At the Luxembourg summit in 1997, the EU accepted the commission's opinion to invite Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia and Cyprus to start talks on their accession to the EU. The negotiation process started on 31 March 1998. Poland finished the accession negotiations in December 2002. Then, the Accession Treaty was signed in Athens on 16 April 2003 (Treaty of Accession 2003). After the ratification of that Treaty in the 2003 Polish European Union membership referendum, Poland and other 9 countries became the members of EU on 1 May 2004.

A8 countries

[edit]Eight of the 10 countries that joined the European Union during the 2004 enlargement are grouped together as the A8, sometimes also referred to as the EU8.[13] They are grouped separately from the other two states that joined Union in 2004, i.e. Cyprus and Malta, because of their relatively similar ex-Eastern block background, per capita income level, Human Development Index level, and most of all the geographical location in mainland Europe, where the two other states from aforementioned 2004 batch are Mediterranean isles.[14][15]

These countries are:

According to BBC News, a reason for grouping the A8 countries was an expectation that they would be the origin for a new wave of increased migration to wealthier European countries.[15] They initially proved to be the origin of a new wave of migration, with many citizens moving from these countries to other states within the EU, later giving a way to newer EU members, including Romania, Bulgaria, and increasing migration from southern Europe after the 2008 financial crisis. After Brexit, the attractiveness of United Kingdom, a market that used to hold the largest share in immigration from A8 states, sharply declined, and the number of EU citizens that left the UK reached new records.[16]

Impact

[edit]

| Member countries | Capital | Population | Area (km2) | GDP (billion US$) |

GDP per capita (US$) |

Languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicosia | 775,927 | 9,250 | 11.681 | 15,054 | Greek Turkish | |

| Prague | 10,246,178 | 78,866 | 105.248 | 10,272 | Czech | |

| Tallinn | 1,341,664 | 45,226 | 22.384 | 16,684 | Estonian | |

| Budapest | 10,032,375 | 93,030 | 102.183 | 10,185 | Hungarian | |

| Riga | 2,306,306 | 64,589 | 24.826 | 10,764 | Latvian | |

| Vilnius | 3,607,899 | 65,200 | 31.971 | 8,861 | Lithuanian | |

| Valletta | 396,851 | 316 | 5.097 | 12,843 | English Maltese | |

| Warsaw | 38,580,445 | 311,904 | 316.438 | 8,202 | Polish | |

| Bratislava | 5,423,567 | 49,036 | 42.800 | 7,810 | Slovak | |

| Ljubljana | 2,011,473 | 20,273 | 29.633 | 14,732 | Slovene | |

| Accession countries | 74,722,685 | 737,690 | 685.123 | 9,169 | 10 new | |

| Existing members (2004) | 381,781,620 | 3,367,154 | 7,711.871 | 20,200 | 12 | |

| EU25 (2004) | 456,504,305 (+19.57%) |

4,104,844 (+17.97%) |

8,396,994 (+8.88%) |

18,394 (−8.94%) |

22 |

| History of the European Union |

|---|

|

|

|

At 12 years after the enlargement, the EU was still "digesting" the change. The influx of new members had effectively put an end to the Franco-German engine behind the EU, as its relatively newer members, Poland and Sweden, set the policy agenda, for example Eastern Partnership. Despite fears of paralysis, the decision-making process had not been hampered by the new membership and if anything the legislative output of the institutions had increased, however justice and home affairs (which operates by unanimity) had suffered. In 2009 the Commission saw the enlargement as a success, but thought that until the enlargement was fully accepted by the public future enlargements would be slow in coming.[11] In 2012 data published by the Guardian showed that that process is complete.[17]

The internal impact has also been relevant. The arrival of additional members has put an additional stress on the governance of the Institutions, and increased significantly overheads (for example, through the multiplication of official languages). Furthermore, there is a division of staff, since the very same day of the enlargement was chosen to enact an in-depth reform of the Staff Regulation, which was intended to bring significant savings in administrative costs. As a result, employment conditions (career & retirement prospects) worsened for officials recruited after that date. Since by definition officials of the "new" Member States were recruited after the enlargement, these new conditions affected all of them (although they also affect nationals of the former 15 Member States who have been recruited after 1 May 2004).

Before the 2004 enlargement, the EU had twelve treaty languages: Danish, Dutch, English, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Irish, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Swedish. However, due to the 2004 enlargement, nine new official languages were added: Polish, Czech, Slovak, Slovene, Hungarian, Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian and Maltese.

Economic impact

[edit]A 2021 study in the Journal of Political Economy found that the 2004 enlargement had aggregate beneficial economic effects on all groups in both the old and new member states. The largest winners were the new member states, in particular unskilled labor in the new member states.[18]

Political impact

[edit]A 2007 study in the journal Post-Soviet Affairs argued that the 2004 enlargement of the EU contributed to the consolidation of democracy in the new member states.[19] In 2009, Freie Universität Berlin political scientist Thomas Risse wrote, "there is a consensus in the literature on Eastern Europe that the EU membership perspective had a huge anchoring effects for the new democracies."[20]

See also

[edit]- Czech Republic and the euro

- Hungary and the euro

- Poland and the euro

- 1973 enlargement of the European Communities

- 1981 enlargement of the European Communities

- 1986 enlargement of the European Communities

- 1995 enlargement of the European Union

- 2007 enlargement of the European Union

- 2013 enlargement of the European Union

- Polexit

- Hungarian withdrawal from the European Union

- Visegrád Group

- Neutral and Non-Aligned European States

References

[edit]- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ White, Michael (21 July 2014). "Twenty years of Tony Blair: totting up the balance sheet". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ "EURLex – e50004 – EN – EUR-Lex". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ EU welcomes 10 new members, CNN 1 May 2004

- ^ See the 10th point of the Presidency Conclusions of the European Council in Luxembourg, 12–13 December 1997, European Council conclusions (1993–2003)

- ^ See the 11th point of the Presidency Conclusions of the European Council in Luxembourg, 12–13 December 1997, European Council conclusions (1993–2003)

- ^ EU-25: Member States grapple with the free labour market, Euractive 17 August 2004

- ^ "Who’s afraid of the EU’s Largest Enlargement? Report on the Impact of Bulgaria and Romania joining the union on Free Movement of People" (archived link), European Citizen Action Service 28 January 2008

- ^ Britons feel better about immigration when Eastern Europeans settle here, Anne-Marie Jeannet, The Times

- ^ EU free movement of labour map, BBC 28 July 2008

- ^ a b EU still 'digesting' 2004 enlargement five years on, EU observer

- ^ Ker-Lindsay, James (2010). "Shifting Alignments The External Orientations of Cyprus since Independence". The Cyprus Review. 22 (2): 67–74.

- ^ Marcel Tirpak. "Migration in EU8 countries" (PDF). Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Stack Exchange. "When the A8 (ex-Eastern Bloc) states acceded, was the process defined by treaty or by the Ordinary Legislative Process?". politics.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Who are the "A8 countries"?". BBC News. 24 April 2005. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Agnieszka Gehringer (9 January 2019). "Brexit: Lower Immigration = Lower Growth". Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Europe in numbers: who gives what in, who gets what out?". The Guardian. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Caliendo, Lorenzo; Parro, Fernando; Opromolla, Luca David; Sforza, Alessandro (2021). "Goods and Factor Market Integration: A Quantitative Assessment of the EU Enlargement". Journal of Political Economy. 129 (12): 3491–3545. doi:10.1086/716560. hdl:10419/171064. ISSN 0022-3808. S2CID 3349273.

- ^ Cameron, David (2007). "Post-Communist Democracy: The Impact of the European Union". Post-Soviet Affairs. 23 (3): 185–217. doi:10.2747/1060-586X.23.3.185. S2CID 18266807.

- ^ Magen, A.; Risse, T.; McFaul, M. (2009). Magen, Amichai; Risse, Thomas; McFaul, Michael A. (eds.). Promoting Democracy and the Rule of Law | SpringerLink. doi:10.1057/9780230244528. ISBN 978-1-349-30559-9.

External links

[edit]- Poland's way to EU Archived 27 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

2004 enlargement of the European Union

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context

Post-Cold War Motivations and Early Preparations

The collapse of communist regimes across Central and Eastern Europe in 1989, culminating in the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, created a geopolitical vacuum that the European Community (EC) viewed as an opportunity to extend its influence eastward. EC leaders prioritized stabilizing nascent democracies to prevent ethnic conflicts, nationalist revivals, or resurgent authoritarianism, as evidenced by early Balkan instabilities, while also aiming to secure the continent's eastern flanks against potential Russian interference.[9] [10] This approach reflected a causal understanding that economic interdependence and institutional ties could lock in reforms, reducing spillover risks from the region, including migration pressures and security threats to Western Europe.[11] Central and Eastern European governments, having shed Soviet domination, pursued EC integration to bolster internal transformations, attract investment, and obtain implicit security guarantees amid uncertainties like the Yugoslav wars starting in 1991.[12] Rather than rushing full membership, which would strain the EC's institutions and budgets, early EC policy emphasized preparatory association to support transition without immediate obligations.[13] By 1990, the EC had coordinated with G-24 donors for emergency aid, signaling commitment to reformist regimes in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia.[14] Key early mechanisms included the PHARE programme, approved by the EC Council in December 1989 and operational from January 1990, which allocated funds—initially €1 billion annually by the mid-1990s—for technical assistance in privatization, legal harmonization, and democratic institution-building, starting with Poland and Hungary before expanding to ten countries.[15] [16] Complementing this, Europe Agreements were signed on 16 December 1991 with Poland and Hungary, establishing political dialogue, gradual tariff reductions on industrial goods (phased over a decade), and commitments to approximate EC laws, with entry into force on 1 February 1994; analogous pacts followed in 1993 for Bulgaria, Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and the Baltic states.[17] These steps prioritized gradual market access over rapid enlargement, reflecting EC calculations that premature accession could undermine both applicant reforms and internal cohesion.[18]Copenhagen Criteria and Candidate Reforms

The Copenhagen European Council, held on 21–22 June 1993, defined the essential criteria for European Union membership, subsequently known as the Copenhagen criteria. These stipulate that candidate countries must achieve stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights, and respect for and protection of minorities; possess a functioning market economy and the capacity to cope with competitive pressures and market forces inside the Union; and demonstrate the ability to assume the obligations of membership, including adherence to the aims of political, economic, and monetary union.[19] The criteria were reinforced at the Madrid European Council in December 1995, emphasizing the need for administrative capacity to implement the acquis communautaire.[20] In preparation for the 2004 enlargement, the ten candidate countries—Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia—pursued targeted reforms across political, economic, and legal domains to satisfy these standards. The European Commission assessed compliance through annual Regular Reports starting in 1998, which evaluated progress against the political criteria (emphasizing democratic consolidation post-communism in Central and Eastern Europe), economic transformation (including privatization and macroeconomic stabilization), and acquis alignment across 31 negotiation chapters encompassing over 80,000 pages of legislation.[21] By October 2002, the Commission concluded that Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Slovenia sufficiently met the Copenhagen criteria, enabling the conclusion of accession negotiations.[22] Political reforms focused on institutional stability and rule of law enhancements. In Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic—former communist states—governments enacted constitutional safeguards for judicial independence, electoral fairness, and minority rights, including Roma protections in Hungary and land restitution laws in Poland to address post-1989 transitions.[3] Anti-corruption agencies were established, such as Poland's Central Anticorruption Bureau in 2006 (building on pre-accession efforts), while Slovakia resolved concerns over media freedom and political interference following its 1998 democratic shift. Cyprus and Malta, as established democracies, emphasized governance continuity but reformed public administration for EU compatibility, with Malta amending its constitution in 2004 to prioritize EU law over conflicting national provisions.[23] Economic reforms prioritized market liberalization and competitiveness. Central and Eastern European candidates privatized state-owned enterprises—Poland divested over 8,000 firms between 1990 and 2003, generating $50 billion in revenue—while implementing fiscal discipline to reduce budget deficits below 3% of GDP as per Maastricht convergence.[3] The Czech Republic restructured its banking sector after 1990s crises, recapitalizing institutions and adopting EU competition rules; Estonia and the Baltic states pioneered flat-tax systems and currency board arrangements for stability. Malta liberalized its trade regime, reducing tariffs from an average 20% to EU levels, and Cyprus strengthened financial supervision amid banking sector growth. These measures, supported by EU pre-accession aid totaling €3.1 billion via PHARE and related programs from 1990–2003, enabled candidates to achieve average GDP growth of 4–6% annually in the late 1990s, fostering resilience to EU market integration.[23][21] Adoption of the acquis demanded legislative harmonization, with candidates transposing approximately 2,000 directives and negotiating transitional periods for sensitive sectors like agriculture and steel. Hungary closed the Chernobyl-style reactors at Paks by 2003 ahead of schedule, while Poland invested €20 billion in environmental upgrades to meet aquis standards on water and air quality. The prospect of membership accelerated these changes, validating the criteria's role in driving verifiable institutional convergence, though uneven implementation persisted in areas like judicial efficiency in some states.[3][22]Negotiation and Accession

Negotiation Phases and Key Agreements

The negotiation process for the 2004 enlargement of the European Union commenced following decisions by successive European Councils to initiate accession talks with applicant states from Central and Eastern Europe, Cyprus, and Malta. At the Luxembourg European Council on 12 and 13 December 1997, the EU launched a structured enlargement process based on the Copenhagen criteria established in 1993, which required candidates to achieve stable institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights, and a functioning market economy capable of withstanding competitive pressures.[24] The Council decided to open bilateral accession negotiations with six countries deemed most advanced in preparations: Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia.[22] These talks formally began on 31 March 1998, focusing on the transposition of the EU acquis communautaire across 31 policy chapters, including internal market rules, agriculture, and justice and home affairs.[22] A subsequent broadening occurred at the Helsinki European Council on 10 and 11 December 1999, which adopted an inclusive approach by granting candidate status to all remaining applicants meeting basic political conditions and deciding to launch negotiations with an additional six countries: Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, and Slovakia.[25] Negotiations with Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia, and Romania opened on 15 February 2000, while Bulgaria's talks started simultaneously; however, Bulgaria and Romania ultimately acceded in 2007 after further reforms.[22] This phase emphasized enhanced pre-accession strategies, including Accession Partnerships tailored to each candidate's priorities for legislative alignment, institution-building, and economic adaptation, monitored through the European Commission's annual Regular Reports assessing compliance with political, economic, and administrative criteria.[22] Negotiations progressed asymmetrically, with frontrunners like Estonia, Poland, and Slovenia closing most chapters by 2001, while laggards addressed rule-of-law deficits and corruption through targeted EU assistance via Phare and other programs totaling over €3 billion annually by 2002. The process concluded at the Copenhagen European Council on 12 and 13 December 2002, where leaders determined that Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia fulfilled the Copenhagen criteria, paving the way for their accession on 1 May 2004 subject to ratification.[26] Key agreements included transitional measures on agriculture funding, structural funds, and free movement of persons, negotiated to mitigate fiscal strains on existing members while committing new states to full acquis adoption by specified deadlines.[26] These outcomes were formalized in the Treaty of Accession signed on 16 April 2003 in Athens, which required unanimous ratification by all 25 prospective members.[22]Accession Treaty Signing and Ratification

The Treaty of Accession 2003, formalizing the entry of ten new member states—Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia—was signed on 16 April 2003 in Athens, Greece, by representatives of the then-15 European Union member states and the ten acceding countries.[27][28] The ceremony occurred at the foot of the Acropolis, symbolizing the integration of Central and Eastern European nations into the EU framework following the conclusion of accession negotiations at the Copenhagen European Council in December 2002.[27] The treaty text, comprising adaptations to existing EU treaties and specific protocols for the new members, was approved unanimously by the European Council and by a large majority in the European Parliament prior to signing.[28] Ratification proceeded in parallel across the 25 states, requiring approval according to each country's constitutional procedures, including parliamentary votes in existing members and a mix of referendums and parliamentary approvals in acceding states.[29] Nine acceding countries—Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and the Czech Republic—conducted national referendums between March and September 2003, all passing with majorities exceeding 50% (e.g., 77% in Lithuania on 10–11 May, 66.8% in Poland on 7–8 June, and 53.5% in Malta on 8 March despite a narrow margin).[30] Cyprus ratified via parliamentary vote without a referendum, reflecting its unicameral legislature's consensus on accession despite ongoing internal divisions.[30] Existing EU members primarily ratified through national parliaments, with no referendums required in most cases, though Denmark and Ireland considered but ultimately handled via legislative processes.[31] The process encountered minimal delays, as pre-accession reforms and transitional safeguards in the treaty addressed concerns over economic disparities and institutional readiness.[29] All 25 ratifications were completed by April 2004, enabling the treaty to enter into force on 1 May 2004, marking the EU's expansion to 25 members.[27] This timeline adhered to the Copenhagen summit's target, with the European Commission verifying compliance throughout.[30]Role of Transitional Arrangements

Transitional arrangements in the 2004 enlargement of the European Union consisted of temporary derogations from immediate full application of the acquis communautaire, primarily targeting the free movement of workers to mitigate anticipated economic disruptions from wage and living standard disparities between acceding states and existing members. These provisions, embedded in the Treaty of Accession signed on 16 April 2003, permitted the EU-15 states to impose restrictions for up to seven years, structured in three phases: an initial two-year period (1 May 2004 to 30 April 2006), followed by an optional three-year extension subject to Commission review, and a final optional two-year period contingent on serious labor market disturbances.[32] The arrangements applied mainly to the eight Central and Eastern European acceders (EU-8: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia), while Cyprus and Malta were granted immediate unrestricted access due to smaller populations and perceived lower migration pressures.[33] The primary rationale for these measures stemmed from concerns over potential mass labor inflows, with acceding states exhibiting GDP per capita levels 40-60% below the EU-15 average and unemployment rates often exceeding 10%, raising fears of wage suppression, increased welfare claims, and sectoral overload in host economies, particularly in border states like Germany and Austria.[34] Only Ireland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom opted out of restrictions, enabling immediate access and subsequently absorbing over 1 million migrants from the EU-8 by 2007, whereas the remaining EU-12 enforced quotas, labor market tests, or priority for nationals, with Germany maintaining controls until 2011 citing ongoing disparities.[35] Periodic reviews, mandated every two to three years, allowed for early liberalization if no disturbances materialized, though extensions were common amid political pressures, such as pre-election anxieties in several EU-15 states.[32] Beyond labor mobility, transitional rules addressed secondary issues like property acquisition by non-nationals and certain public procurement thresholds, but these were less contentious and phased out more rapidly.[36] Overall, the arrangements played a pivotal role in securing ratification of the accession treaty by assuaging domestic opposition in EU-15 legislatures, where surveys indicated 40-50% public apprehension toward enlargement-driven migration, thereby enabling the geopolitical and economic unification of post-communist states without derailing the process. Empirical assessments post-accession revealed limited net fiscal burdens in restricting states and positive remittances to origin countries (e.g., Poland received €4 billion annually by 2007), validating the phased approach's utility in managing asymmetric integration shocks.[33][37]Profiles of New Member States

Central and Eastern European Acceders

The Central and Eastern European acceders in the 2004 enlargement included eight post-communist states: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. These nations, which had transitioned from Soviet-era or satellite communist systems after 1989–1991, sought EU membership to secure democratic stability, foster market-oriented reforms, and integrate into Western economic structures following the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and Comecon.[38] Negotiations for their accession opened in March 1998, building on Europe Agreements signed in the early 1990s that established association and trade preferences.[39] All eight states ratified accession treaties signed on 16 April 2003, joining the EU on 1 May 2004 after fulfilling the Copenhagen criteria through legislative harmonization, institutional strengthening, and economic liberalization.[1] Prior to accession, these countries demonstrated varying degrees of economic convergence with the EU-15 average. In 2003, GDP per capita (in purchasing power standards) stood at 73% for the Czech Republic, 76% for Slovenia, 62% for Hungary, 50% for Estonia and Poland, 49% for Lithuania and Slovakia, and 41% for Latvia.[38] Reforms emphasized privatization of state-owned enterprises, fiscal stabilization, and adoption of competition policies to establish functioning market economies capable of withstanding competitive pressures.[3] Politically, they anchored transitions via constitutional democracies and referendums approving membership, such as Estonia's September 2003 vote with 66.9% in favor at over 63% turnout, and the Czech Republic's June 2003 referendum yielding 77% approval.[40][41] Poland, the largest by population at approximately 38 million, represented over half the new entrants' populace, amplifying its influence.[42] Subregional groupings highlighted diverse paths: the Visegrád countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia) focused on industrial restructuring and foreign investment attraction, while Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) prioritized rapid liberalization and IT sector growth amid proximity to Russia. Slovenia, emerging from Yugoslav dissolution, emphasized export-led manufacturing. These states collectively added about 66 million citizens, shifting the EU's center eastward and necessitating transitional measures for agriculture and labor markets.[43] Accession demanded alignment with over 80,000 pages of the acquis, spurring judiciary independence, anti-corruption measures, and minority rights protections, though implementation challenges persisted in areas like public administration.[3]Mediterranean Acceders: Cyprus and Malta

The Republic of Cyprus and Malta, small Mediterranean island states, acceded to the European Union on 1 May 2004 as part of the fifth enlargement wave, increasing the EU's membership from 15 to 25 states.[29] Both nations had applied for membership in July 1990, but their paths diverged due to domestic politics and geopolitical constraints.[44] Cyprus, with a population of approximately 650,000 in the government-controlled areas, faced unique challenges stemming from the island's division since Turkey's 1974 military intervention, which left the northern third under Turkish Cypriot administration.[45] Malta, with around 400,000 inhabitants, navigated internal partisan divides over integration.[46] Accession for both required alignment with the Copenhagen criteria, including stable democratic institutions, rule of law, human rights protections, and a functioning market economy capable of withstanding competitive pressures.[23] For Cyprus, negotiations commenced in November 1998 alongside five Central European candidates, focusing on adapting its legal framework to the EU acquis communautaire.[47] The European Commission assessed that Cyprus fulfilled the political criteria by 2002, with stable institutions despite the ongoing division.[48] Economic alignment progressed, though the island's economy, reliant on services, tourism, and shipping, required adjustments for competition. A key precondition involved the failed UN-mediated Annan Plan for reunification, put to simultaneous referendums on 24 April 2004: 75.83% of Greek Cypriots rejected it, while 64.9% of Turkish Cypriots approved.[49] [50] Despite this, the Treaty of Accession applied fully to areas controlled by the Republic of Cyprus, with the acquis suspended indefinitely in the north, rendering it de jure but not de facto EU territory there.[51] This arrangement preserved Cyprus's membership while isolating the effects of non-compliance in the occupied areas.[52] Malta's accession process was marked by political volatility. After initial application, the Labour government froze negotiations in 1996, resuming them in 1998 under the pro-EU Nationalist Party.[53] Negotiations opened formally in February 2000, concluding by December 2002 after reforms in public administration, judiciary independence, and market liberalization to meet Copenhagen standards.[23] A non-binding referendum on 8 March 2003 saw 53.74% vote in favor of membership, though turnout was 91%.[53] Opponents, led by the Labour Party, contested the result's decisiveness, prompting a snap general election on 12 April 2003, where Nationalists secured a narrow victory, confirming the path to accession.[54] Malta's economy, dominated by tourism, financial services, and manufacturing, benefited from transitional safeguards on property acquisition and fisheries, reflecting its small-scale vulnerabilities.[55] Both states signed the Accession Treaty on 16 April 2003 in Athens, ratifying it domestically before the 1 May 2004 entry.[1] Cyprus's entry amid unresolved division highlighted the EU's prioritization of the internationally recognized Republic's compliance over full territorial unification, while Malta's demonstrated the role of electoral mandates in overcoming Euroskepticism.[56] These accessions added strategic Mediterranean outposts, enhancing the EU's southern flank without immediate northern Cyprus integration.[57]Immediate Integration Dynamics

Implementation of Free Movement

The 2004 Treaty of Accession permitted existing European Union member states (EU-15) to impose transitional arrangements restricting free movement of workers from the eight Central and Eastern European new members (EU-8: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia) for up to seven years, with mandatory reviews after two and five years to assess labor market impacts and potential easing.[33] These measures aimed to mitigate anticipated surges in migration that could strain social systems or depress wages in higher-income states, though Cyprus and Malta faced no such labor restrictions for their citizens.[33] Ireland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom opted for immediate full access without transitional barriers, enabling unrestricted entry for work purposes from May 1, 2004.[33] The remaining twelve EU-15 states enacted varying restrictions, often requiring work permits, quotas, or priority for domestic workers, with durations tied to economic disparity thresholds between origin and host countries.[58] For instance, Germany and Austria applied the full seven-year period initially, citing proximity and large wage gaps, while others like the Netherlands and Denmark imposed shorter two-year limits before lifting.[36] Safeguard clauses allowed temporary reimposition if "serious disturbances" arose, though none were activated post-2004.[34] The United Kingdom implemented a Worker Registration Scheme to track EU-8 migrants accessing employment or benefits, excluding self-employed and initially limiting in-work benefits for the first year.[59]| EU-15 State | Transitional Policy for EU-8 Workers |

|---|---|

| Ireland | Full immediate access[33] |

| Sweden | Full immediate access[33] |

| United Kingdom | Full immediate access with registration scheme[33][59] |

| Others (e.g., Germany, France, etc.) | Restrictions up to 7 years, with phased reviews[33][58] |