Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

ATPase

View on Wikipedia| Adenosinetriphosphatase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 3.6.1.3 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9000-83-3 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| |||||||||

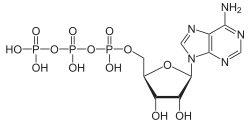

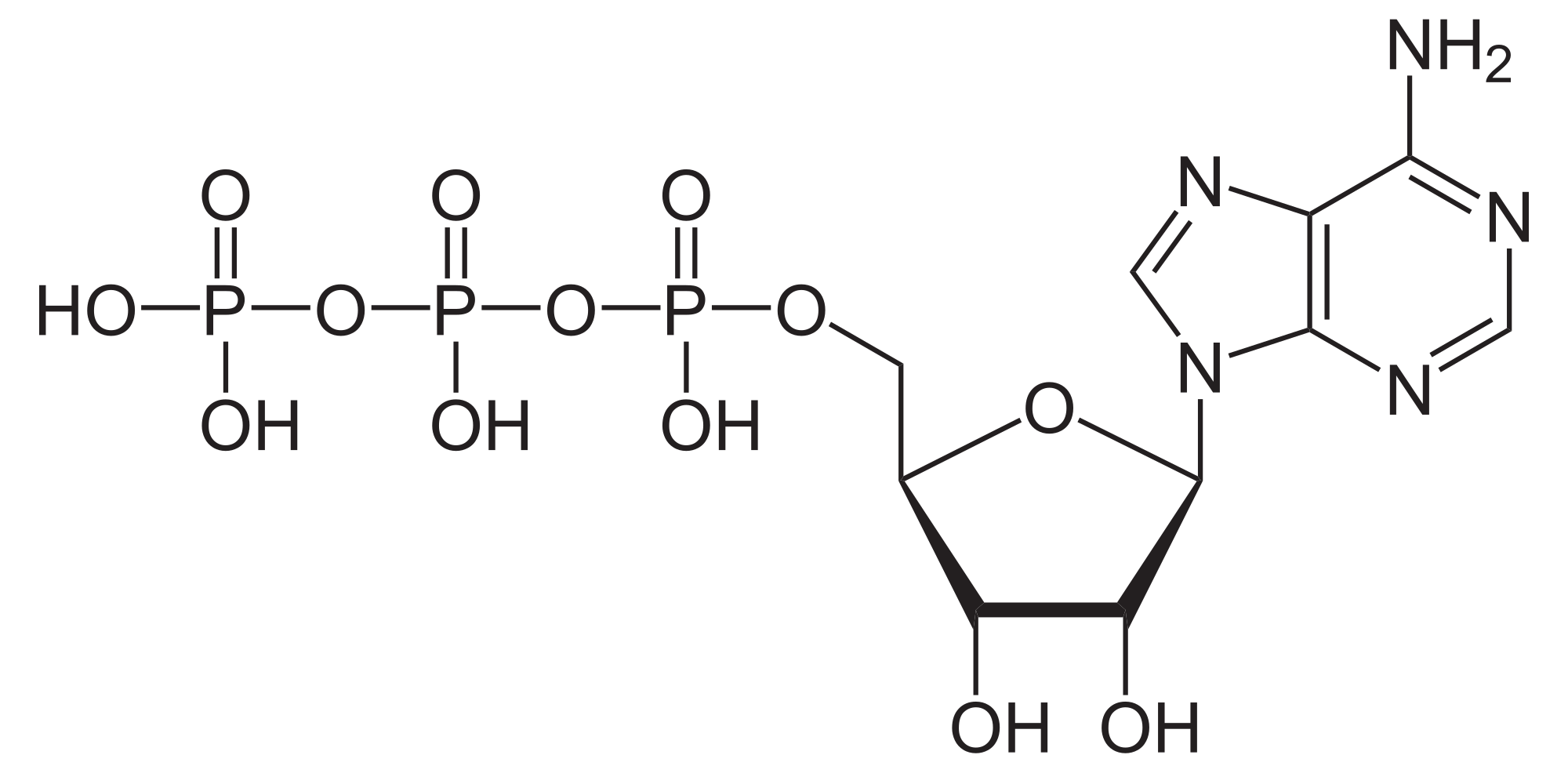

ATPases (EC 3.6.1.3, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, ATP hydrolase, adenosine triphosphatase) are a class of enzymes that catalyze the decomposition of ATP into ADP and a free phosphate ion[1][2][3][4][5][6] or the inverse reaction. This dephosphorylation reaction releases energy, which the enzyme (in most cases) harnesses to drive other chemical reactions that would not otherwise occur. This process is widely used in all known forms of life.

Some such enzymes are integral membrane proteins (anchored within biological membranes), and move solutes across the membrane, typically against their concentration gradient. These are called transmembrane ATPases.

Functions

[edit]

Transmembrane ATPases import metabolites necessary for cell metabolism and export toxins, wastes, and solutes that can hinder cellular processes. An important example is the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ATPase) that maintains the cell membrane potential. Another example is the hydrogen potassium ATPase (H+/K+ATPase or gastric proton pump) that acidifies the contents of the stomach. ATPase is genetically conserved in animals; therefore, cardenolides which are toxic steroids produced by plants that act on ATPases, make general and effective animal toxins that act dose dependently.[7]

Besides exchangers, other categories of transmembrane ATPase include co-transporters and pumps (however, some exchangers are also pumps). Some of these, like the Na+/K+ATPase, cause a net flow of charge, but others do not. These are called electrogenic transporters and electroneutral transporters, respectively.[8] Genetic variants in ATPases result in a wide spectrum of human diseases, from prenatal to later onset disease.[9][10]

Structure

[edit]The Walker motifs are a telltale protein sequence motif for nucleotide binding and hydrolysis. Beyond this broad function, the Walker motifs can be found in almost all natural ATPases, with the notable exception of tyrosine kinases.[11] The Walker motifs commonly form a Beta sheet-turn-Alpha helix that is self-organized as a Nest (protein structural motif). This is thought to be because modern ATPases evolved from small NTP-binding peptides that had to be self-organized.[12]

Protein design has been able to replicate the ATPase function (weakly) without using natural ATPase sequences or structures. Importantly, while all natural ATPases have some beta-sheet structure, the designed "Alternative ATPase" lacks beta sheet structure, demonstrating that this life-essential function is possible with sequences and structures not found in nature.[13]

Mechanism

[edit]ATPase (also called FoF1-ATP Synthase) is a charge-transferring complex that catalyzes ATP to perform ATP synthesis by moving ions through the membrane.[14]

The coupling of ATP hydrolysis and transport is a chemical reaction in which a fixed number of solute molecules are transported for each ATP molecule hydrolyzed; for the Na+/K+ exchanger, this is three Na+ ions out of the cell and two K+ ions inside per ATP molecule hydrolyzed.

Transmembrane ATPases make use of ATP's chemical potential energy by performing mechanical work: they transport solutes in the opposite direction of their thermodynamically preferred direction of movement—that is, from the side of the membrane with low concentration to the side with high concentration. This process is referred to as active transport.

For instance, inhibiting vesicular H+-ATPases would result in a rise in the pH within vesicles and a drop in the pH of the cytoplasm.

All of the ATPases share a common basic structure. Each rotary ATPase is composed of two major components: Fo/A0/V0 and F1/A1/V1. They are connected by 1-3 stalks to maintain stability, control rotation, and prevent them from rotating in the other direction. One stalk is utilized to transmit torque.[15] The number of peripheral stalks is dependent on the type of ATPase: F-ATPases have one, A-ATPases have two, and V-ATPases have three. The F1 catalytic domain is located on the N-side (negative-side) of the membrane and is involved in the synthesis and degradation of ATP and is involved in oxidative phosphorylation. The Fo transmembrane domain is involved in the movement of ions across the membrane.[14]

The bacterial FoF1-ATPase consists of the soluble F1 domain and the transmembrane Fo domain, which is composed of several subunits with varying stoichiometry. There are two subunits, γ, and ε, that form the central stalk and they are linked to Fo. Fo contains a c-subunit oligomer in the shape of a ring (c-ring). The α subunit is close to the subunit b2 and makes up the stalk that connects the transmembrane subunits to the α3β3 and δ subunits. F-ATP synthases are identical in appearance and function except for the mitochondrial FoF1-ATP synthase, which contains 7-9 additional subunits.[14]

The electrochemical potential is what causes the c-ring to rotate in a clockwise direction for ATP synthesis. This causes the central stalk and the catalytic domain to change shape. Rotating the c-ring causes three ATP molecules to be made, which then causes H+ to move from the P-side (positive-side) of the membrane to the N-side (negative-side) of the membrane. The counterclockwise rotation of the c-ring is driven by ATP hydrolysis and ions move from the N-side to the P-side, which helps to build up electrochemical potential.[14]

Transmembrane ATP synthases

[edit]The ATP synthase of mitochondria and chloroplasts is an anabolic enzyme that harnesses the energy of a transmembrane proton gradient as an energy source for adding an inorganic phosphate group to a molecule of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to form a molecule of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

This enzyme works when a proton moves down the concentration gradient, giving the enzyme a spinning motion. This unique spinning motion bonds ADP and P together to create ATP.

ATP synthase can also function in reverse, that is, use energy released by ATP hydrolysis to pump protons against their electrochemical gradient.

Classification

[edit]There are different types of ATPases, which can differ in function (ATP synthesis and/or hydrolysis), structure (F-, V- and A-ATPases contain rotary motors) and in the type of ions they transport.

- Rotary ATPases[16][17]

- F-ATPases (F1FO-ATPases) in mitochondria, chloroplasts and bacterial plasma membranes are the prime producers of ATP, using the proton gradient generated by oxidative phosphorylation (mitochondria) or photosynthesis (chloroplasts).[18]

- F-ATPases lacking a delta/OSCP subunit move sodium ions instead. They are proposed to be called N-ATPases, since they seem to form a distinct group that is further apart from usual F-ATPases than A-ATPases are from V-ATPases.[19]

- V-ATPases (V1VO-ATPases) are primarily found in eukaryotic vacuoles, catalysing ATP hydrolysis to transport solutes and lower pH in organelles like proton pump of lysosome.

- A-ATPases (A1AO-ATPases) are found in Archaea and some extremophilic bacteria. They are arranged like V-ATPases, but function like F-ATPases mainly as ATP synthases.

- Many homologs that are not necessarily rotaty exist. See ATP synthase § Evolution.

- F-ATPases (F1FO-ATPases) in mitochondria, chloroplasts and bacterial plasma membranes are the prime producers of ATP, using the proton gradient generated by oxidative phosphorylation (mitochondria) or photosynthesis (chloroplasts).[18]

- P-ATPases (E1E2-ATPases) are found in bacteria, fungi and in eukaryotic plasma membranes and organelles, and function to transport a variety of different ions across membranes.

- E-ATPases are cell-surface enzymes that hydrolyze a range of NTPs, including extracellular ATP. Examples include ecto-ATPases, CD39s, and ecto-ATP/Dases, all of which are members of a "GDA1 CD39" superfamily.[20]

- AAA proteins are a family of ring-shaped P-loop NTPases.

P-ATPase

[edit]P-ATPases (sometime known as E1-E2 ATPases) are found in bacteria and also in eukaryotic plasma membranes and organelles. Its name is due to short time attachment of inorganic phosphate at the aspartate residues at the time of activation. Function of P-ATPase is to transport a variety of different compounds, like ions and phospholipids, across a membrane using ATP hydrolysis for energy. There are many different classes of P-ATPases, which transports a specific type of ion. P-ATPases may be composed of one or two polypeptides, and can usually take two main conformations, E1 and E2.

Human genes

[edit]- Na+/K+ transporting: ATP1A1, ATP1A2, ATP1A3, ATP1A4, ATP1B1, ATP1B2, ATP1B3, ATP1B4

- Ca2+ transporting: ATP2A1, ATP2A2, ATP2A3, ATP2B1, ATP2B2, ATP2B3, ATP2B4, ATP2C1, ATP2C2

- H+/K+ exchanging: ATP4A

- H+ transporting, mitochondrial: ATP5A1, ATP5B, ATP5C1, ATP5C2, ATP5D, ATP5E, ATP5F1, ATP5MC1, ATP5G2, ATP5G3, ATP5H, ATP5I, ATP5J, ATP5J2, ATP5L, ATP5L2, ATP5O, ATP5S, MT-ATP6, MT-ATP8

- H+ transporting, lysosomal: ATP6AP1, ATP6AP2, ATP6V1A, ATP6V1B1, ATP6V1B2, ATP6V1C1, ATP6V1C2, ATP6V1D, ATP6V1E1, ATP6V1E2, ATP6V1F, ATP6V1G1, ATP6V1G2, ATP6V1G3, ATP6V1H, ATP6V0A1, ATP6V0A2, ATP6V0A4, ATP6V0B, ATP6V0C, ATP6V0D1, ATP6V0D2, ATP6V0E

- Cu2+ transporting: ATP7A, ATP7B

- Class I, type 8: ATP8A1, ATP8B1, ATP8B2, ATP8B3, ATP8B4

- Class II, type 9: ATP9A, ATP9B

- Class V, type 10: ATP10A, ATP10B, ATP10D

- Class VI, type 11: ATP11A, ATP11B, ATP11C

- H+/K+ transporting, nongastric: ATP12A

- type 13: ATP13A1, ATP13A2, ATP13A3, ATP13A4, ATP13A5

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Geider K, Hoffmann-Berling H (1981). "Proteins controlling the helical structure of DNA". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 50: 233–60. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.001313. PMID 6267987.

- ^ Kielley WW (1961). "Myosin adenosine triphosphatase". In Boyer PD, Lardy H, Myrbäck K (eds.). The Enzymes. Vol. 5 (2nd ed.). New York: Academic Press. pp. 159–168.

- ^ Martin SS, Senior AE (November 1980). "Membrane adenosine triphosphatase activities in rat pancreas". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 602 (2): 401–18. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(80)90320-x. PMID 6252965.

- ^ Njus D, Knoth J, Zallakian M (1981). "Proton-linked transport in chromaffin granules". Current Topics in Bioenergetics. 11: 107–147. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-152511-8.50010-4.

- ^ Riley MV, Peters MI (June 1981). "The localization of the anion-sensitive ATPase activity in corneal endothelium". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 644 (2): 251–6. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(81)90382-5. PMID 6114746.

- ^ Tjian R (1981). "Regulation of Viral Transcription and DNA Replication by the SV40 Large T Antigen". Initiation Signals in Viral Gene Expression. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 93. pp. 5–24. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-68123-3_2. ISBN 978-3-642-68125-7. PMID 6269805.

- ^ Dobler S, Dalla S, Wagschal V, Agrawal AA (August 2012). "Community-wide convergent evolution in insect adaptation to toxic cardenolides by substitutions in the Na,K-ATPase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (32): 13040–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1202111109. PMC 3420205. PMID 22826239.

- ^ "3.2: Transport in Membranes". Biology LibreTexts. 21 January 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Smith, Richard S.; Florio, Marta; Akula, Shyam K.; Neil, Jennifer E.; Wang, Yidi; Hill, R. Sean; Goldman, Melissa; Mullally, Christopher D.; Reed, Nora; Bello-Espinosa, Luis; Flores-Sarnat, Laura; Monteiro, Fabiola Paoli; Erasmo, Casella B.; Pinto e Vairo, Filippo; Morava, Eva; Barkovich, A. James; Gonzalez-Heydrich, Joseph; Brownstein, Catherine A.; McCarroll, Steven A.; Walsh, Christopher A. (22 June 2021). "Early role for a Na + ,K + -ATPase ( ATP1A3 ) in brain development". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (25). doi:10.1073/pnas.2023333118. PMC 8237684. PMID 34161264.

- ^ Brashear, Allison; Sweadner, Kathleen J.; Haq, Ihtsham; Napoli, Eleonora; Ozelius, Laurie (1993). "ATP1A3-Related Disorder". GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301294. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020.

- ^ Walker JE, Saraste M, Runswick MJ, Gay NJ (1982). "Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold". EMBO J. 1 (8): 945–51. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. PMC 553140. PMID 6329717.

- ^ Romero Romero ML, Yang F, Lin YR, Toth-Petroczy A, Berezovsky IN, Goncearenco A, et al. (December 2018). "Simple yet functional phosphate-loop proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (51): E11943 – E11950. Bibcode:2018PNAS..11511943R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1812400115. PMC 6304952. PMID 30504143.

- ^ Wang M, Hecht MH (August 2020). "A Completely De Novo ATPase from Combinatorial Protein Design". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 142 (36): 15230–15234. Bibcode:2020JAChS.14215230W. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c02954. PMID 32833456.

- ^ a b c d Calisto F, Sousa FM, Sena FV, Refojo PN, Pereira MM (February 2021). "Mechanisms of Energy Transduction by Charge Translocating Membrane Proteins". Chemical Reviews. 121 (3): 1804–1844. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00830. PMID 33398986.

- ^ Hahn A, Parey K, Bublitz M, Mills DJ, Zickermann V, Vonck J, et al. (August 2016). "Structure of a Complete ATP Synthase Dimer Reveals the Molecular Basis of Inner Mitochondrial Membrane Morphology". Molecular Cell. 63 (3): 445–456. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.037. PMC 4980432. PMID 27373333.

- ^ Stewart AG, Laming EM, Sobti M, Stock D (April 2014). "Rotary ATPases--dynamic molecular machines". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 25: 40–8. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2013.11.013. PMID 24878343.

- ^ Kühlbrandt W, Davies KM (January 2016). "Rotary ATPases: A New Twist to an Ancient Machine". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 41 (1): 106–116. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2015.10.006. PMID 26671611.

- ^ Watanabe R, Noji H (April 2013). "Chemomechanical coupling mechanism of F(1)-ATPase: catalysis and torque generation". FEBS Letters. 587 (8): 1030–1035. Bibcode:2013FEBSL.587.1030W. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.063. PMID 23395605.

- ^ Dibrova DV, Galperin MY, Mulkidjanian AY (June 2010). "Characterization of the N-ATPase, a distinct, laterally transferred Na+-translocating form of the bacterial F-type membrane ATPase". Bioinformatics. 26 (12): 1473–1476. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq234. PMC 2881411. PMID 20472544.

- ^ Knowles AF (March 2011). "The GDA1_CD39 superfamily: NTPDases with diverse functions". Purinergic Signalling. 7 (1): 21–45. doi:10.1007/s11302-010-9214-7. PMC 3083126. PMID 21484095.

External links

[edit]- "ATP synthase - a splendid molecular machine"

- ATPase at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Electron microscopy structures of ATPases from the EM Data Bank(EMDB)

ATPase

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Nomenclature

ATPases are a diverse family of enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi), releasing free energy that drives various cellular processes:This enzymatic activity is classified primarily under the Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers 3.6.3.- for ATP hydrolases acting on acid anhydrides without translocation and 7.1.2.- for certain proton-translocating ATPases, reflecting updates in the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB) nomenclature to account for their roles in ion transport.[5] The nomenclature of ATPases derives from their functional role as ATP phosphohydrolases, with the general Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry number 9000-83-3 assigned to adenosine triphosphatase.[6] Specific subtypes are denoted by letters indicating structural and mechanistic features, such as P-type (phosphorylating) ATPases, F-type (factor-dependent) ATPases, V-type (vacuolar) ATPases, and A-type (archaeal) ATPases, each linked to dedicated entries in biochemical databases like BRENDA and KEGG for detailed annotation and pathway integration.[7] These classifications facilitate the organization of the superfamily based on shared catalytic domains and transport capabilities. A key distinction exists between ATPases and ATP synthases: while ATPases predominantly hydrolyze ATP to perform work such as ion pumping or mechanical motion, ATP synthases—often reversible F-type ATPases—can operate in the opposite direction, synthesizing ATP from ADP and Pi using a proton motive force across membranes.[8] This reversibility highlights the bidirectional potential of certain rotary ATPases but underscores that ATPases are defined by their hydrolysis-dominant function in most physiological contexts.[9] ATPases exhibit remarkable evolutionary conservation, with homologs present across all domains of life, from prokaryotes like bacteria and archaea to eukaryotes, reflecting their ancient origin and essential role in energy homeostasis predating the last universal common ancestor.[10] This broad distribution is evidenced by phylogenetic analyses of core subunits, which trace rotary mechanisms back over 3.5 billion years.[11]