Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

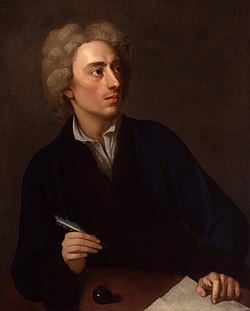

Alexander Pope

View on Wikipedia

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S.[1] – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature,[2] Pope is best known for his satirical and discursive poetry including An Essay on Criticism (1711), The Rape of the Lock (1712–1717), The Dunciad (1728–1743), and for his translations of Homer.

Key Information

Pope is often quoted in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, some of his verses having entered common parlance (e.g. "damning with faint praise" or "to err is human; to forgive, divine").

Life

[edit]Alexander Pope was born in London on 21 May 1688 during the year of the Glorious Revolution. His father Alexander Pope was a successful linen merchant in the Strand, London. His mother was Edith Turner, a daughter of William Turner, Esquire, of York. Both parents were Catholics.[3] His uncle-in-law was the miniature painter Samuel Cooper, through his mother's sister, Christiana. Pope's education was affected by the recently enacted Test Acts, a series of English penal laws that upheld the status of the established Church of England, banning Catholics from teaching, attending a university, voting, and holding public office on penalty of perpetual imprisonment. Pope was taught to read by his aunt and attended Twyford School circa 1698.[3] He also attended two Roman Catholic schools in London.[3] Such schools, though still illegal, were tolerated in some areas.[4]

In 1700 his family moved to a small estate at Popeswood, in Binfield, Berkshire, close to the royal Windsor Forest.[3] This was due to strong anti-Catholic sentiment and a statute preventing "Papists" from living within 10 miles (16 km) of London or Westminster.[5] Pope would later describe the countryside around the house in his poem Windsor Forest.[6] Pope's formal education ended at this time, and from then on, he mostly educated himself by reading the works of classical writers such as the satirists Horace and Juvenal, the epic poets Homer and Virgil, as well as English authors such as Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare and John Dryden.[3] He studied many languages, reading works by French, Italian, Latin, and Greek poets. After five years of study, Pope came into contact with figures from London literary society such as William Congreve, Samuel Garth and William Trumbull.[3][4]

At Binfield he made many important friends. One of them, John Caryll (the future dedicatee of The Rape of the Lock), was twenty years older than the poet and had made many acquaintances in the London literary world. He introduced the young Pope to the ageing playwright William Wycherley and to William Walsh, a minor poet, who helped Pope revise his first major work, The Pastorals. There, he met the Blount sisters, Teresa and Martha (Patty), in 1707. He remained close friends with Patty until his death, but his friendship with Teresa ended in 1722.[7]

From the age of 12 he suffered numerous health problems, including Pott disease, a form of tuberculosis that affects the spine, which deformed his body and stunted his growth, leaving him with a severe hunchback. His tuberculosis infection caused other health problems including respiratory difficulties, high fevers, inflamed eyes and abdominal pain.[3] He grew to a height of only 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 metres). Pope was already removed from society as a Catholic, and his poor health alienated him further. Although he never married, he had many female friends to whom he wrote witty letters, including Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. It has been alleged that his lifelong friend Martha Blount was his lover.[4][8][9][10] His friend William Cheselden said, according to Joseph Spence, "I could give a more particular account of Mr. Pope's health than perhaps any man. Cibber's slander (of carnosity) is false. He had been gay [happy], but left that way of life upon his acquaintance with Mrs. B."[11]

In May 1709, Pope's Pastorals was published in the sixth part of bookseller Jacob Tonson's Poetical Miscellanies. This earned Pope instant fame and was followed by An Essay on Criticism, published in May 1711, which was equally well received.

Around 1711, Pope made friends with Tory writers Jonathan Swift, Thomas Parnell and John Arbuthnot, who together formed the satirical Scriblerus Club. Its aim was to satirise ignorance and pedantry through the fictional scholar Martinus Scriblerus. He also made friends with Whig writers Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. In March 1713, Windsor Forest[6] was published to great acclaim.[4]

During Pope's friendship with Joseph Addison, he contributed to Addison's play Cato, as well as writing for The Guardian and The Spectator. Around this time, he began the work of translating the Iliad, which was a painstaking process – publication began in 1715 and did not end until 1720.[4]

In 1714 the political situation worsened with the death of Queen Anne and the disputed succession between the Hanoverians and the Jacobites, leading to the Jacobite rising of 1715. Though Pope, as a Catholic, might have been expected to have supported the Jacobites because of his religious and political affiliations, according to Maynard Mack, "where Pope himself stood on these matters can probably never be confidently known".[citation needed] These events led to an immediate downturn in the fortunes of the Tories, and Pope's friend Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, fled to France. This was added to by the Impeachment of the former Tory Chief Minister Lord Oxford.

Pope lived in his parents' house in Mawson Row, Chiswick, between 1716 and 1719; the red-brick building is now the Mawson Arms, commemorating him with a blue plaque.[12]

The money made from his translation of Homer allowed Pope to move in 1719 to a villa at Twickenham, where he created his now-famous grotto and gardens. The serendipitous discovery of a spring during the excavation of the subterranean retreat enabled it to be filled with the relaxing sound of trickling water, which would quietly echo around the chambers. Pope was said to have remarked, "Were it to have nymphs as well – it would be complete in everything." Although the house and gardens have long since been demolished, much of the grotto survives beneath Radnor House Independent Co-educational School.[8][13] The grotto has been restored and will open to the public for 30 weekends a year from 2023 under the auspices of Pope's Grotto Preservation Trust.[14]

Poetry

[edit]

An Essay on Criticism

[edit]An Essay on Criticism was first published anonymously on 15 May 1711. Pope began writing the poem early in his career and took about three years to finish it.

At the time the poem was published, its heroic couplet style was quite a new poetic form and Pope's work an ambitious attempt to identify and refine his own positions as a poet and critic. It was said to be a response to an ongoing debate on the question of whether poetry should be natural, or written according to predetermined artificial rules inherited from the classical past.[15]

The "essay" begins with a discussion of the standard rules that govern poetry, by which a critic passes judgement. Pope comments on the classical authors who dealt with such standards and the authority he believed should be accredited to them. He discusses the laws to which a critic should adhere while analysing poetry, pointing out the important function critics perform in aiding poets with their works, as opposed to simply attacking them.[16] The final section of An Essay on Criticism discusses the moral qualities and virtues inherent in an ideal critic, whom Pope claims is also the ideal man.

The Rape of the Lock

[edit]Pope's most famous poem is The Rape of the Lock, first published in 1712, with a revised version in 1714. A mock-epic, it satirises a high-society quarrel between Arabella Fermor (the "Belinda" of the poem) and Lord Petre, who had snipped a lock of hair from her head without permission. The satirical style is tempered, however, by a genuine, almost voyeuristic interest in the "beau-monde" (fashionable world) of 18th-century society.[17] The revised, extended version of the poem focuses more clearly on its true subject: the onset of acquisitive individualism and a society of conspicuous consumers. In the poem, purchased artefacts displace human agency and "trivial things" come to dominate.[18]

The Dunciad and Moral Essays

[edit]

Though The Dunciad first appeared anonymously in Dublin, its authorship was not in doubt. Pope pilloried a host of other "hacks", "scribblers" and "dunces" in addition to Theobald, and Maynard Mack has accordingly called its publication "in many ways the greatest act of folly in Pope's life". Though a masterpiece due to having become "one of the most challenging and distinctive works in the history of English poetry", writes Mack, "it bore bitter fruit. It brought the poet in his own time the hostility of its victims and their sympathizers, who pursued him implacably from then on with a few damaging truths and a host of slanders and lies."[19]

According to his half-sister Magdalen Rackett, some of Pope's targets were so enraged by The Dunciad that they threatened him physically. "My brother does not seem to know what fear is," she told Joseph Spence, explaining that Pope loved to walk alone, so went accompanied by his Great Dane Bounce, and for some time carried pistols in his pocket.[20] This first Dunciad, along with John Gay's The Beggar's Opera and Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, joined in a concerted propaganda assault against Robert Walpole's Whig ministry and the financial revolution it stabilised. Although Pope was a keen participant in the stock and money markets, he never missed a chance to satirise the personal, social and political effects of the new scheme of things. From The Rape of the Lock onwards, these satirical themes appear constantly in his work.

In 1731, Pope published his "Epistle to Burlington", on the subject of architecture, the first of four poems later grouped as the Moral Essays (1731–1735).[21] The epistle ridicules the bad taste of the aristocrat "Timon".[22] For example, the following are verses 99 and 100 of the Epistle:

At Timon's Villa let us paſs a day,

Where all cry out, "What ſums are thrown away!"[22]

Pope's foes claimed he was attacking the Duke of Chandos and his estate, Cannons. Though the charge was untrue, it did much damage to Pope.[citation needed]

There has been some speculation on a feud between Pope and Thomas Hearne, due in part to the character of Wormius in The Dunciad, who is seemingly based on Hearne.[23]

An Essay on Man

[edit]An Essay on Man is a philosophical poem in heroic couplets published between 1732 and 1734. Pope meant it as the centrepiece of a proposed system of ethics to be put forth in poetic form. It was a piece that he sought to make into a larger work, but he did not live to complete it.[24] It attempts to "vindicate the ways of God to Man", a variation on Milton's attempt in Paradise Lost to "justify the ways of God to Man" (1.26). It challenges as prideful an anthropocentric worldview. The poem is not solely Christian, however. It assumes that man has fallen and must seek his own salvation.[24]

Consisting of four epistles addressed to Lord Bolingbroke, it presents an idea of Pope's view of the Universe: no matter how imperfect, complex, inscrutable and disturbing the Universe may be, it functions in a rational fashion according to natural laws, so that the Universe as a whole is a perfect work of God, though to humans it appears to be evil and imperfect in many ways. Pope ascribes this to our limited mindset and intellectual capacity. He argues that humans must accept their position in the "Great Chain of Being", at a middle stage between the angels and the beasts of the world. Accomplish this and we potentially could lead happy and virtuous lives.[24]

The poem is an affirmative statement of faith: life seems chaotic and confusing to man in the centre of it, but according to Pope it is truly divinely ordered. In Pope's world, God exists and is what he centres the Universe around as an ordered structure. The limited intelligence of man can only take in tiny portions of this order and experience only partial truths, hence man must rely on hope, which then leads to faith. Man must be aware of his existence in the Universe and what he brings to it in terms of riches, power and fame. Pope proclaims that man's duty is to strive to be good, regardless of other situations.[25][failed verification]

Later life and works

[edit]FATHER of all! in every age,

In every clime adored,

By saint, by savage, and by sage,

Jehovah, Jove, or Lord!

If I am right, thy grace impart

Still in the right to stay;

If I am wrong, O, teach my heart

To find that better way!

Save me alike from foolish pride,

Or impious discontent,

At aught thy wisdom has denied,

Or aught thy goodness lent.

Teach me to feel another's woe,

To hide the fault I see;

That mercy I to others show,

That mercy show to me.

Mean though I am, not wholly so,

Since quickened by thy breath;

O, lead me wheresoe'er I go,

Through this day's life or death!

To thee, whose temple is all space,

Whose altar, earth, sea, skies!

One chorus let all Being raise!

All Nature's incense rise!

The Imitations of Horace that followed (1733–1738) were written in the popular Augustan form of an "imitation" of a classical poet, not so much a translation of his works as an updating with contemporary references. Pope used the model of Horace to satirise life under George II, especially what he saw as the widespread corruption tainting the country under Walpole's influence and the poor quality of the court's artistic taste. Pope added as an introduction to Imitations a wholly original poem that reviews his own literary career and includes famous portraits of Lord Hervey ("Sporus"), Thomas Hay, 9th Earl of Kinnoull ("Balbus") and Addison ("Atticus").

In 1738 came "The Universal Prayer".[27]

Among the younger poets whose work Pope admired was Joseph Thurston.[28] After 1738, Pope himself wrote little. He toyed with the idea of composing a patriotic epic in blank verse called Brutus, but only the opening lines survive. His major work in those years was to revise and expand his masterpiece, The Dunciad. Book Four appeared in 1742 and a full revision of the whole poem the following year. Here Pope replaced the "hero" Lewis Theobald with the Poet Laureate, Colley Cibber as "king of dunces". However, the real focus of the revised poem is Walpole and his works. By now Pope's health, which had never been good, was failing. When told by his physician, on the morning of his death, that he was better, Pope replied: "Here am I, dying of a hundred good symptoms."[29][30] He died at his villa surrounded by friends on 30 May 1744, about eleven o'clock at night. On the previous day, 29 May 1744, Pope had called for a priest and received the Last Rites of the Catholic Church. He was buried in the nave of St Mary's Church, Twickenham.

Translations and editions

[edit]The Iliad

[edit]Pope had been fascinated by Homer since childhood. In 1713, he announced plans to publish a translation of the Iliad. The work would be available by subscription, with one volume appearing every year over six years. Pope secured a revolutionary deal with the publisher Bernard Lintot, which earned him 200 guineas (£210) a volume, a vast sum at the time.

His Iliad translation appeared between 1715 and 1720. It was acclaimed by Samuel Johnson as "a performance which no age or nation could hope to equal". Conversely, the classical scholar Richard Bentley wrote: "It is a pretty poem, Mr. Pope, but you must not call it Homer."[31]

The Odyssey

[edit]

Encouraged by the success of the Iliad, Bernard Lintot published Pope's five-volume translation of Homer's Odyssey in 1725–1726.[32] For this Pope collaborated with William Broome and Elijah Fenton: Broome translated eight books (2, 6, 8, 11, 12, 16, 18, 23), Fenton four (1, 4, 19, 20) and Pope the remaining twelve. Broome provided the annotations.[33] Pope tried to conceal the extent of the collaboration, but the secret leaked out.[34] It did some damage to Pope's reputation for a time, but not to his profits.[35] Leslie Stephen considered Pope's portion of the Odyssey inferior to his version of the Iliad, given that Pope had put more effort into the earlier work – to which, in any case, his style was better suited.[36]

Shakespeare's works

[edit]In this period, Pope was employed by the publisher Jacob Tonson to produce an opulent new edition of Shakespeare.[37] When it appeared in 1725, it silently regularised Shakespeare's metre and rewrote his verse in several places. Pope also removed about 1,560 lines of Shakespeare's material, arguing that some appealed to him more than others.[37] In 1726, the lawyer, poet and pantomime-deviser Lewis Theobald published a scathing pamphlet called Shakespeare Restored, which catalogued the errors in Pope's work and suggested several revisions to the text. This enraged Pope, wherefore Theobald became the main target of Pope's Dunciad.[38]

The second edition of Pope's Shakespeare appeared in 1728.[37] Apart from some minor revisions to the preface, it seems that Pope had little to do with it. Most later 18th-century editors of Shakespeare dismissed Pope's creatively motivated approach to textual criticism. Pope's preface continued to be highly rated. It was suggested that Shakespeare's texts were thoroughly contaminated by actors' interpolations and they would influence editors for most of the 18th century.

Spirit, skill and satire

[edit]Pope's poetic career testifies to an indomitable spirit despite disadvantages of health and circumstance. The poet and his family were Catholics and so fell subject to the prohibitive Test Acts, which hampered their co-religionists after the abdication of James II. One of these banned them from living within ten miles of London, another from attending public school or university. So except for a few spurious Catholic schools, Pope was largely self-educated. He was taught to read by his aunt and became a book lover, reading in French, Italian, Latin and Greek and discovering Homer at the age of six. In 1700, when only twelve years of age, he wrote his poem Ode on Solitude.[39][40] As a child Pope survived once being trampled by a cow, but when he was 12 he began struggling with tuberculosis of the spine (Pott disease), which restricted his growth, so that he was only 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 metres) tall as an adult. He also suffered from crippling headaches.

In the year 1709, Pope showcased his precocious metrical skill with the publication of Pastorals, his first major poems. They earned him instant fame. By the age of 23, he had written An Essay on Criticism, released in 1711. A kind of poetic manifesto in the vein of Horace's Ars Poetica, it met with enthusiastic attention and won Pope a wider circle of prominent friends, notably Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, who had recently begun to collaborate on the influential The Spectator. The critic John Dennis, having found an ironic and veiled portrait of himself, was outraged by what he saw as the impudence of a younger author. Dennis hated Pope for the rest of his life, and save for a temporary reconciliation, dedicated his efforts to insulting him in print, to which Pope retaliated in kind, making Dennis the butt of much satire.

A folio containing a collection of his poems appeared in 1717, along with two new ones about the passion of love: Verses to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady and the famous proto-romantic poem Eloisa to Abelard. Though Pope never married, about this time he became strongly attached to Lady M. Montagu, whom he indirectly referenced in his popular Eloisa to Abelard, and to Martha Blount, with whom his friendship continued through his life.

As a satirist, Pope made his share of enemies as critics, politicians and certain other prominent figures felt the sting of his sharp-witted satires. Some were so virulent that Pope even carried pistols while walking his dog. In 1738 and thenceforth, Pope composed relatively little. He began having ideas for a patriotic epic in blank verse titled Brutus, but mainly revised and expanded his Dunciad. Book Four appeared in 1742; and a complete revision of the whole in the year that followed. At this time Lewis Theobald was replaced with the Poet Laureate Colley Cibber as "king of dunces", but his real target remained the Whig politician Robert Walpole.

Reception

[edit]By the mid-18th century, new fashions in poetry emerged. A decade after Pope's death, Joseph Warton claimed that Pope's style was not the most excellent form of the art. The Romantic movement that rose to prominence in early 19th-century England was more ambivalent about his work. Though Lord Byron identified Pope as one of his chief influences – believing his own scathing satire of contemporary English literature English Bards and Scotch Reviewers to be a continuance of Pope's tradition – William Wordsworth found Pope's style too decadent to represent the human condition.[4] George Gilfillan in an 1856 study called Pope's talent "a rose peering into the summer air, fine, rather than powerful".[41]

Pope's reputation revived in the 20th century. His work was full of references to the people and places of his time, which aided people's understanding of the past. The post-war period stressed the power of Pope's poetry, recognising that Pope's immersion in Christian and Biblical culture lent depth to his poetry. For example, Maynard Mack, in the late 20th-century, argued that Pope's moral vision demanded as much respect as his technical excellence. Between 1953 and 1967 the definitive Twickenham edition of Pope's poems appeared in ten volumes, including an index volume.[4]

Works

[edit]Major works

[edit]- 1709: Pastorals

- 1711: An Essay on Criticism[42]

- 1712: Messiah (from the Book of Isaiah, and later translated into Latin by Samuel Johnson)

- 1712: The Rape of the Lock (enlarged in 1714)[42]

- 1713: Windsor Forest[6][42]

- 1715: The Temple of Fame: A Vision[43]

- 1717: Eloisa to Abelard[42]

- 1717: Three Hours After Marriage, with others

- 1717: Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady[42]

- 1728: Peri Bathous, Or the Art of Sinking in Poetry

- 1728: The Dunciad[42]

- 1731–1735: Moral Essays

- 1733–1734: Essay on Man[42]

- 1735: Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot

Translations and editions

[edit]- 1715–1720: Translation of the Iliad[42]

- 1723–1725: The Works of Shakespear, in Six Volumes

- 1725–1726: Translation of the Odyssey[42]

Other works

[edit]- 1700: Ode on Solitude

- 1713: Ode for Musick[44]

- 1715: A Key to the Lock

- 1717: The Court Ballad[45]

- 1717: Ode for Music on St. Cecilia's Day

- 1731: An Epistle to the Right Honourable Richard Earl of Burlington[46]

- 1733: The Impertinent, or A Visit to the Court[47]

- 1736: Bounce to Fop[48]

- 1737: The First Ode of the Fourth Book of Horace[49]

- 1738: The First Epistle of the First Book of Horace[50]

Editions

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Goldsmith, Netta Murray (2002), Alexander Pope: The Evolution of a Poet, p. 17: "Alexander Pope was born on Monday 21 May 1688 at 6.45 pm when England was on the brink of a revolution." This date in the Gregorian calendar is a Friday. The equivalent New Style date is 31 May.

- ^ "Alexander Pope". Poetry Foundation. 29 April 2021. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Erskine-Hill, Howard (2004). "Pope, Alexander (1688–1744)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22526 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g "Alexander Pope", Literature Online biography (Chadwyck-Healey: Cambridge, 2000). (subscription required)

- ^ "An Act to prevent and avoid dangers which may grow by Popish Recusants" (3 Jas. 1. c. 4). For details, see Catholic Encyclopedia, "Penal Laws Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ a b c Pope, Alexander. Windsor-Forest Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Rumbold, Valerie (1989). Women's Place in Pope's World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 33, 48, 128. ISBN 978-0-521-36308-2.

- ^ a b Gordon, Ian (24 January 2002). "An Epistle to a Lady (Moral Essay II)". The Literary Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ "Martha Blount". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ The Life of Alexander Pope, by Robert Carruthers, 1857, with a corrupted and badly scanned version available from Internet Archive, or as an even worse 23MB PDF. For reference to his relationship with Martha Blount and her sister, see pp. 64–68 (p. 89 ff. of the PDF). In particular, discussion of the controversy over whether the relationship was sexual is described in some detail on pp. 76–78.

- ^ Zachary Cope (1953) William Cheselden, 1688–1752. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone, p. 89.

- ^ Clegg, Gillian. "Chiswick History". People: Alexander Pope. chiswickhistory.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ London Evening Standard, 2 November 2010.

- ^ Fox, Robin Lane (23 July 2021). "The secrets and lights of Alexander Pope's Twickenham grotto". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Pat (2006). The Major Works. Oxford University Press. pp. 17–39. ISBN 019920361X.

- ^ Baines, Paul (2001). The Complete Critical Guide to Alexander Pope. Routledge Publishing. pp. 67–90.

- ^ "from the London School of Journalism". Archived from the original on 31 May 2008.

- ^ Colin Nicholson (1994). Writing and the Rise of Finance: Capital Satires of the Early Eighteenth Century, Cambridge.

- ^ Maynard Mack (1985). Alexander Pope: A Life. W. W. Norton & Company, and Yale University Press, pp. 472–473. ISBN 0393305295

- ^ Joseph Spence. Observations, Anecdotes, and Characters of Books and Men, Collected from the Conversation of Mr. Pope (1820), p. 38 Archived 2 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Moral Essays". Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ a b Alexander Pope. Moral Essays Archived 21 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, p. 82

- ^ Rogers, Pat (2004). The Alexander Pope encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-06153-X. OCLC 607099760.

- ^ a b c Nuttal, Anthony (1984). Pope's Essay on Man. Allen & Unwin. pp. 3–15, 167–188. ISBN 9780048000170.

- ^ Cassirer, Ernst (1944). An Essay on Man; an introduction to a philosophy of human culture. Yale University Press.ISBN 9780300000344

- ^ A Library of Poetry and Song: Being Choice Selections from The Best Poets. With An Introduction by William Cullen Bryant, New York, J. B. Ford and Company, 1871, pp. 269-270.

- ^ McKeown, Trevor W. "Alexander Pope 'Universal Prayer'". bcy.ca. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2007. Full-text Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Also at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ James Sambrook (2004) "Thurston, Josephlocked (1704–1732)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/70938

- ^ Ruffhead, Owen (1769). The Life of Alexander Pope; With a Critical Essay on His Writings and Genius. p. 475.

- ^ Dyce, Alexander (1863). The Poetical Works of Alexander Pope, with a Life, by A. Dyce. p. cxxxi.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel (1791). The Lives of the Most Eminent Poets with Critical Observations on their Works. Vol. IV. London: Printed for J. Rivington & Sons, and 39 others. p. 193. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Homer (1725–1726). The Odyssey of Homer. Translated by Alexander Pope; William Broome & Elijah Fenton (1st ed.). London: Bernard Lintot.

- ^ Fenton, Elijah (1796). The poetical works of Elijah Fenton with the life of the author. Printed for, and under the direction of, G. Cawthorn, British Library, Strand. p. 7. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ Fraser, George (1978). Alexander Pope. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 9780710089908.

- ^ Damrosch, Leopold (1987). The Imaginative World of Alexander Pope. University of California Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780520059757.

- ^ Stephen, Sir Leslie (1880). Alexander Pope. Harper & Brothers. pp. 80.

- ^ a b c "Preface to Shakespeare, 1725, Alexander Pope". ShakespeareBrasileiro. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "Lewis Theobald" Archived 14 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Genetic studies of genius by Lewis Madison Terman Stanford University Press, 1925 OCLC: 194203

- ^ "Personhood, Poethood, and Pope: Johnson's Life of Pope and the Search for the Man Behind the Author" by Mannheimer, Katherine. Eighteenth-Century Studies - Volume 40, Number 4, Summer 2007, pp. 631-649 MUSE Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ George Gilfillan (1856) "The Genius and Poetry of Pope", The Poetical Works of Alexander Pope, Vol. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cox, Michael, editor, The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-860634-6

- ^ Alexander Pope (1715) The Temple of Fame: A Vision. London: Printed for Bernard Lintott. Print.

- ^ Pope, Alexander. ODE FOR MUSICK. Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. The Court Ballad Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. Epistle to Richard Earl of Burlington Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. The IMPERTINENT, or A Visit to the COURT. A SATYR. Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. Bounce to Fop Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. THE FIRST ODE OF THE FOURTH BOOK OF HORACE. Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. THE FIRST EPISTLE OF THE FIRST BOOK OF HORACE. Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

Bibliography

[edit]- "The Author as Editor: Congreve and Pope in Context."The Book Collector 41 (no 1) Spring, 1992:9-27.

- Davis, Herbert, ed. (1966). Poetical Works. Oxford Standard Authors. London: Oxford U.P.

- Mack, Maynard (1985). Alexander Pope. A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rogers, Pat (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Alexander Pope. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tillotson, Geoffrey (2nd ed. 1950). On the Poetry of Pope. Oxford, at the Clarendon Press.

- Tillotson, Geoffrey (1958). Pope and Human Nature. Oxford, at the Clarendon Press.

External links

[edit]- Alexander Pope at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

- Works by Alexander Pope at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Alexander Pope at the Internet Archive

- Works by Alexander Pope at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- John Wilkes and Alexander Pope – UK Parliament Living Heritage

- Lennox, Patrick Joseph (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12.

- Minto, William; Bryant, Margaret (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). pp. 82–87.

- BBC audio file. In Our Time, radio 4 discussion of Pope.

- University of Toronto "Representative Poetry Online" page on Pope

- Pope's Grave

- The Twickenham Museum Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Pope's Grotto Preservation Trust

- Richmond Libraries' Local Studies Collection. Local History. Accessed 2010-10-19

- "Archival material relating to Alexander Pope". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Alexander Pope at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Images relating to Alexander Pope Archived 31 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine at the English Heritage Archive

- Blue Plaque at 110 Chiswick Lane South, Chiswick, London W4 2LR

Alexander Pope

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Family

Alexander Pope was born on 21 May 1688 in London to Catholic parents of modest mercantile means.[6] His father, also named Alexander Pope (1646–1717), had worked as a linen merchant in Lombard Street before retiring early on the proceeds of his trade, reportedly amassing around £20,000; the elder Pope's background traced to respectable but unremarkable Protestant ancestry in Sussex, with a conversion to Catholicism later in life. Pope's mother, Edith Turner (1643–1733), was the daughter of William Turner, a merchant and alderman of York, and came from a large family of at least seventeen children; she had previously been wed to a Mr. Rackett, by whom she had a daughter, making Pope an only child in his parents' second marriage but with a half-sister, Magdalen Rackett.[7] [8] The family's adherence to Roman Catholicism placed them under legal disabilities in post-Revolution England, where Catholics faced restrictions on property ownership, education, and residence near London; these constraints prompted the Popes to relocate from the city around 1690 to Kensington or Hammersmith, and later to a small estate at Binfield in Windsor Forest by 1700, seeking rural seclusion and proximity to fellow Catholic gentry.[1] The elder Pope, described as quiet and devout, devoted his later years to managing family finances and a small property, while Edith Pope, illiterate but memorably sharp-witted, maintained a close, protective bond with her son, outliving him by a decade and inheriting his estate. This Catholic merchant milieu, insulated from aristocratic pretensions yet financially secure, shaped Pope's early worldview amid the era's sectarian tensions, with no evidence of noble lineage despite occasional later claims by the poet himself.Health and Physical Deformities

Alexander Pope contracted a severe spinal ailment around the age of 12, shortly after his family's relocation from London to Binfield in 1700.[9] This condition, widely attributed to Pott's disease—a form of tuberculous spondylitis affecting the vertebrae—resulted in progressive kyphosis, or hunchback, and stunted his growth to an adult height of 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 meters).[10][11] While some historical analyses propose alternative etiologies such as trauma or congenital spinal weakness, the tubercular origin aligns with contemporary medical understanding of the era's prevalent bone tuberculosis, which eroded vertebral structures and caused angular deformities.[10][12] The deformity impaired Pope's posture and mobility, rendering his torso disproportionately elongated relative to his limbs, a characteristic noted by contemporaries and later physicians.[13] Accompanying symptoms included chronic respiratory distress from restricted thoracic expansion, recurrent migraines, fevers, and impaired vision, which compounded his physical frailty and necessitated frequent medical interventions, including orthopedic supports.[13][14] These afflictions persisted lifelong, exacerbating vulnerabilities to secondary infections and contributing to his self-described "long disease, my life" in correspondence.[13] Despite such debilities, Pope's intellect remained undiminished, though the condition fueled satirical attacks from rivals who mocked his appearance as emblematic of moral or intellectual flaws.[12]Religious Upbringing and Restrictions

Alexander Pope was born on 21 May 1688 to devout Catholic parents in London: his father, Alexander Pope Sr. (1646–1717), a linen merchant who had converted from Protestantism, and his mother, Edith Turner (c. 1643–1733), the daughter of Catholic converts from clerical families.[15][3] The family's adherence to Roman Catholicism placed them under severe legal disabilities in England following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which installed Protestant monarchs William III and Mary II and intensified anti-Catholic penal laws.[16] These statutes, building on earlier Elizabethan and Restoration-era restrictions, prohibited Catholics from inheriting or purchasing land exceeding certain limits, practicing law or medicine, serving in public office, voting, or educating children in public institutions, with penalties including fines, imprisonment, or property confiscation for violations.[17][16] Pope's early education was profoundly shaped by these prohibitions, as Catholics were excluded from Oxford, Cambridge, and grammar schools established under Protestant oversight.[18] From around age 6 to 12, he attended clandestine Catholic seminaries—first at Twyford School near Winchester, then briefly at St. Mary's Catholic boarding school in Hyde Park Corner—where he studied Latin and Greek under priests, but his formal schooling ceased early due to health issues and the precarious legality of such institutions.[19] Thereafter, Pope pursued self-directed learning at home, mastering French, Italian, and classical languages through private tutors, family resources, and personal diligence, compensating for the absence of university access.[19][3] The family's 1700 relocation to Binfield, Windsor Forest, partly reflected strategies to evade urban scrutiny and property restrictions, as Pope Sr. retired from trade around 1710 and later moved to Chiswick and Twickenham, adhering to faith amid ongoing disenfranchisement.[16] These constraints fostered Pope's lifelong Catholic identity, which he maintained without public recantation despite social and professional marginalization; he faced exclusion from literary patronage tied to establishment figures and navigated suspicions during events like the 1715 Jacobite rising, though evidence shows no direct involvement in plots.[15][20] Penal laws persisted until partial relief in 1778, but for Pope, they reinforced a sense of alienation, evident in his poetry's themes of exile and moral independence, while precluding conventional career paths and compelling reliance on writing for livelihood.[16][20]Literary Career

Early Publications and Influences

Pope's initial foray into print came with his Pastorals, a set of four eclogues published in Jacob Tonson's Poetical Miscellanies: The Sixth Part in May 1709.[1] Written in heroic couplets, these poems idealized rural life through seasonal vignettes—January, Summer, Autumn, and Winter—and marked his debut as a practitioner of neoclassical forms, earning notice for their polished diction and musicality despite his youth of 21.[6] The work's inclusion in a prominent anthology alongside pieces by Ambrose Philips sparked a literary rivalry, with Pope's more ornate style contrasting Philips's simpler "Dorick" mode, as later debated in periodicals.[6] The following year, in 1711, Pope anonymously released An Essay on Criticism, a 744-line didactic poem composed over several years and printed by subscription on May 15.[6] This verse essay codified rules for poetic judgment, emphasizing imitation of nature, classical models, and restraint against excess, with lines like "True Wit is Nature to advantage dress'd" encapsulating its Horatian balance of instruction and delight.[1] Though it provoked hostility from established critics such as John Dennis, who decried its presumptuousness in a pamphlet, the poem solidified Pope's standing in London literary circles by demonstrating his mastery of rhyme and argument.[6] Pope's early style was shaped by intensive self-study of classical texts in Latin and Greek, begun in childhood despite formal education barriers from his Catholic faith.[21] He drew directly from Virgil for pastoral and georgic structures, Homer for epic scope, Horace for satirical epistles, Ovid for metamorphic narratives, and Quintilian for rhetorical principles, adapting these to English verse.[21][1] Contemporaneous English influences included John Dryden, whose heroic couplets and translations Pope refined for greater concision and wit, as seen in his emulation of Dryden's Mac Flecknoe for mock-heroic potential.[1] He also absorbed elements from native forebears—Chaucer's moral acuity, Spenser's allegorical richness, Milton's sublime diction, Shakespeare's dramatic vitality, and Donne's metaphysical conceits—fusing them into a neoclassical synthesis that prioritized order, decorum, and empirical observation over romantic effusion.[21] This foundation, honed through imitation and translation exercises, enabled Pope's rapid ascent, as evidenced by Windsor-Forest (1713), a georgic tribute to the Treaty of Utrecht and rural harmony, which extended his classical borrowings into political topography.[6]Breakthrough Works

An Essay on Criticism, published anonymously on 15 May 1711 when Pope was 23, established his reputation as a poet and critic through its verse epistle in heroic couplets, distilling principles of literary judgment drawn from classical sources like Horace and Boileau.[22][23] The work's aphoristic lines, such as "To err is human, to forgive divine," encapsulated neoclassical ideals of balance, decorum, and the unity of sound and sense, earning immediate praise for its precocity and polish from figures in London's literary circles.[18] Its reception propelled Pope into prominence, with critics noting its maturity despite the author's youth and lack of formal education, signaling his command of satire and moral insight.[24] Building on this success, The Rape of the Lock, first issued in two cantos in May 1712 and expanded to five in 1714, solidified Pope's fame with a mock-heroic satire on a trivial society scandal involving the surreptitious cutting of a lock of hair from Arabella Fermor.[18] Drawing from Homer and Virgil for epic machinery—supernatural sylphs guarding female virtue—the poem lampooned aristocratic vanities, consumerism, and gender frivolities while reconciling the feuding families at its core.[25] Its witty deflation of heroic conventions and vivid tableau of 18th-century toilette rituals garnered widespread acclaim, positioning Pope as a master of light verse capable of profound social commentary and boosting subscriptions for his future projects.[1] By 1714, these works had transformed Pope from an obscure Catholic outsider into a central figure in Augustan literature, attracting patrons and rivals alike.[2]Homer Translations and Financial Independence

In 1713, at age 25, Alexander Pope contracted with publisher Bernard Lintot to translate Homer's Iliad into English heroic couplets, a project that spanned 1715 to 1720 across six volumes published via subscription.[26] This innovative model secured around 750 special subscribers initially, with broader participation yielding Pope approximately £5,000 in earnings, equivalent to substantial wealth for the era and marking a pioneering success in author-driven publishing.[26][27] These proceeds enabled Pope to lease a villa in Twickenham in 1719, establishing a retreat that symbolized his emerging autonomy from financial dependence on patrons or lesser commissions.[26] Building on the Iliad's acclaim, Pope undertook the Odyssey translation from 1725 to 1726, collaborating with William Broome and Elijah Fenton for portions while retaining primary oversight and profits; this effort further capitalized on subscription enthusiasm, reinforcing his economic security.[28] The combined revenues from both Homeric works, totaling over £10,000, afforded Pope lifelong financial independence, allowing withdrawal from exhaustive translation labors to pursue original satire and philosophy unencumbered by pecuniary pressures.[29] This self-sustained status, rare for poets of his time amid Catholic disabilities limiting institutional support, underscored the causal link between his translational enterprise and personal liberty.[26]Major Works

An Essay on Criticism

An Essay on Criticism is a didactic poem composed by Alexander Pope around 1709 and first published anonymously in London on 15 May 1711 by printer Bernard Lintot.[30] Written in heroic couplets, the work spans 744 lines across three parts and serves as a verse essay articulating principles of sound literary criticism and poetic composition.[31] Pope, then in his early twenties, aimed to instruct aspiring critics on avoiding common pitfalls while advocating adherence to classical rules derived from nature and antiquity.[32] The poem's first part (lines 1–200) outlines ideal critic qualities, stressing the need for humility, extensive learning, and balance between wit and judgment to discern true art that mirrors nature's order.[33] Pope warns against superficial knowledge, famously stating, "A little learning is a dang'rous thing; / Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring," to highlight how partial education leads to erroneous judgments.[30] Influences include Horace's Ars Poetica, Aristotle's Poetics, and Nicolas Boileau's L'Art poétique (1674), which Pope adapts to English neoclassical tastes by prioritizing imitation of the ancients while allowing for modern application.[32] In the second part (lines 201–559), he catalogs critics' faults—such as pedantry, envy, and affectation—arguing these stem from personal vices rather than objective flaws in works, and urges self-examination to "Follow Nature, as she leads."[34] The third part (lines 560–744) shifts to positive prescriptions for critics and poets alike, advocating rules not as rigid constraints but as guides to achieve harmony, with lines like "True Wit is Nature to advantage dress'd, / What oft was thought, but ne'er so well express'd" encapsulating the neoclassical ideal of refined expression.[30] Pope emphasizes forgiveness in judgment—"To err is human, to forgive divine"—while critiquing innovation untethered from tradition.[33] Upon publication, the poem received acclaim for its epigrammatic polish and received multiple editions by 1713, cementing Pope's reputation as a master of satire and versification amid the Augustan era's emphasis on decorum.[31] Scholarly analyses note its role in defending hierarchical literary standards against emerging empiricist challenges, though some contemporaries viewed its prescriptions as overly prescriptive.[35]The Rape of the Lock

The Rape of the Lock originated as a response to a minor social scandal among English Catholic aristocracy in 1711, when 21-year-old Robert, Lord Petre, clandestinely cut a lock of hair from the head of Arabella Fermor during a gathering, igniting a prolonged family feud between the Petres and Fermors.[36][25] Alexander Pope, a mutual acquaintance and fellow Catholic facing his own societal restrictions, was encouraged by family friend John Caryll to compose a light verse reconciling the parties through humor rather than reproach.[25][37] The poem debuted anonymously in a two-canto form in May 1712, included in Bernard Lintot's Miscellaneous Poems and Translations, a collection of contemporary works that helped circulate Pope's early efforts despite his youth—he was 23 at publication.[38] Pope revised and expanded it to five cantos by 1714, releasing the version under his own name with added supernatural elements, including the dedication to Arabella Fermor (as "Belinda"), which Lintot printed to capitalize on the poem's growing popularity.[39] This iteration, spanning 794 lines in heroic couplets, solidified its status as Pope's breakthrough satirical work.[38] Employing mock-heroic conventions, the poem parodies epic structures from Homer and Virgil—invoking muses, divine interventions, and battle scenes—to trivialize upper-class vanities, with "rape" denoting seizure rather than violation, emphasizing the lock's theft as a pseudo-epic outrage.[37] Pope introduces airy "sylphs" as guardian spirits (drawn from Rosicrucian lore outlined in a prefatory letter), who flit invisibly to protect Belinda's chastity amid courtship rituals, contrasting their ethereal fragility with human pettiness.[25] The narrative unfolds across cantos depicting Belinda's elaborate morning toilette as heroic arming, a tense ombre card game symbolizing amorous combat, the Baron's (Petre's analogue) scissors-aided theft amid a mock battle of beaux and belles, and the lock's cosmic apotheosis into a star.[39][37] Central themes target the superficiality and moral vacuity of early 18th-century polite society, satirizing female vanity through Belinda's obsession with beauty aids and male gallantry reduced to predatory trifling, while questioning the era's gender imbalances where women's honor hinges on minutiae like hair.[37] Pope critiques aristocratic idleness and commodified courtship, elevating card-table disputes to Iliadic wars to expose how trivial disputes eclipse substantive ethics, yet he tempers outright condemnation with witty detachment, preserving social order's facade.[36] The sylphs underscore causal fragility: unseen forces govern human folly, but intervention fails against willful excess, reflecting Pope's deterministic view of hierarchy and restraint.[25] Upon release, the poem garnered acclaim for its inventive burlesque, forging Pope's reputation as a master versifier amid Augustan neoclassicism, though some contemporaries missed its reconciling intent, viewing it as perpetuating gossip.[38] Its enduring appeal lies in precise couplet machinery—rhymed iambic pentameter enabling epigrammatic satire—and enduring dissection of modernity's polite hypocrisies, influencing later mock-epics while highlighting Pope's skill in distilling empirical social observation into universal ridicule.[39]The Dunciad

The Dunciad is a mock-heroic satirical poem by Alexander Pope that lampoons the proliferation of dullness, hack writing, and literary mediocrity in early 18th-century England. Initially published anonymously on May 28, 1728, as The Dunciad: An Heroic Poem in three books, it presents the goddess Dulness—personifying intellectual and artistic vacuity—as reigning over a chaotic realm of inept authors, critics, and publishers who compete in absurd contests to crown a "king of dunces."[40][41] The poem employs heroic couplets and parodies classical epics like Virgil's Aeneid and Milton's Paradise Lost, inverting epic grandeur to depict games of folly such as producing bad verse or pedantic scholarship, culminating in Dulness's triumph over wit and reason.[1] Pope composed the work amid personal feuds, particularly targeting Lewis Theobald, who had criticized Pope's 1726 edition of Shakespeare in Shakespeare Restored (1712), positioning Theobald as the initial "hero" (renamed Tibbald) and son of Dulness.[42] Other prominent targets include playwright Colley Cibber (later elevated to hero), bookseller Edmund Curll, poet laureate Elkanah Settle, and a host of minor scribblers, opera promoters, and pseudo-scholars, whom Pope catalogs in footnotes to amplify the ridicule.[42] The satire extends beyond individuals to critique broader cultural decay, portraying London as a hub of commercialized trash literature that erodes classical standards and promotes superficiality over substance.[43] A 1729 edition, The Dunciad Variorum, expanded the original with mock-scholarly annotations mimicking pedantic commentary traditions, further deriding the targets through fabricated "variations" and prolegomena attributed to the fictional Martinus Scriblerus.[44] Pope revised the poem extensively in response to events, publishing The New Dunciad in 1742 as a single fourth book and integrating it into a complete four-book version in 1743, where Cibber supplanted Theobald as the dunce king to reflect Cibber's perceived embodiment of theatrical vulgarity and court favoritism.[45][1] These variants, produced over 15 years, reflect Pope's evolving assault on modernity's "entropy of literature," with the final iteration warning of Dulness's universal engulfment in a prophecy of cultural apocalypse.[46]An Essay on Man and Moral Essays

An Essay on Man (1733–1734) is a philosophical poem composed in heroic couplets, divided into four epistles that explore humanity's position within the divine order of the universe.[47] The work posits that apparent imperfections in creation serve a greater harmony, encapsulated in the line "Whatever is, is right," reflecting an optimistic view of providence where partial evil contributes to universal good.[48] Pope draws on rationalist ideas akin to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz's principle of the "best of all possible worlds," though direct influence remains debated among scholars, with some attributing parallels to shared Enlightenment themes rather than explicit borrowing.[49] Initially published anonymously, the poem gained wide readership across Europe, prompting translations and early admiration from figures like Voltaire, who later critiqued its optimism in Candide (1759) amid reflections on real-world suffering.[50] The Moral Essays, a series of four verse epistles published between 1731 and 1735, address ethical and social conduct through satirical observation, later unified under that title by editor William Warburton in 1751.[51] Epistle IV, "To Richard Earl of Burlington" (1731), critiques architectural taste and extravagance, advocating balanced aesthetics rooted in nature and utility.[52] Epistle III, "To Allen Lord Bathurst" (1732), examines the moral use of riches, warning against avarice and excess while praising stewardship that benefits society.[51] Epistle I, "To C. Lord Cobham" (1734), analyzes human character formation, attributing virtues and vices to innate dispositions interacting with environment, and employs irony to dissect inconsistencies in moral judgment.[53] Epistle II, "Of the Characters of Women" (1735), satirizes feminine foibles like vanity and caprice, using hyperbolic wit to probe gender-specific ethical lapses without descending into outright misogyny, as Pope targets universal human folly.[54] Collectively, these works exemplify Pope's neoclassical commitment to order and reason in ethics, blending Horatian satire with empirical observation of vice to promote self-knowledge and hierarchical virtue.[55] Critics note the essays' resistance to abstract moralizing, favoring concrete examples drawn from contemporary society to illustrate causal links between passion, habit, and moral outcome.[53] While some modern analyses highlight ironic undercurrents that question rigid ethical norms, period reception valued their defense of traditional values against emerging sentimentalism.[56]Philosophical and Political Views

Defense of Hierarchy and Order

In An Essay on Man (1733–1734), Alexander Pope defended hierarchy as an intrinsic feature of divine creation, encapsulated in the concept of the Great Chain of Being, a continuous scale descending from God through spiritual and material entities to the inert. This structure ensures universal order by assigning each being a fixed position, where deviation invites discord: "Vast chain of being! which from God began, / Natures ethereal, human, Angel, Man, / Beast, Bird, Fish, Insect, what no Eye can see, / No Glass can reach! from Infinite to thee, / From thee to Nothing."[57] Pope contended that human pride in questioning this arrangement—such as probing God's motives—disrupts the chain's integrity, as partial knowledge cannot comprehend the whole design, rendering such inquiries futile and presumptuous.[58] Pope extended this metaphysical hierarchy to human faculties and society, arguing that reason's limits necessitate acceptance of subordinate roles for harmony. In Epistle II, he delineates internal hierarchies—instincts below passions, passions below reason—warning that inverting them breeds vice, as "The bliss of man (could pride that blessing find) / Is not to act or think beyond mankind."[59] Causally, he linked ordered hierarchies to empirical stability: just as natural subordination prevents chaos among species, human societies thrive under analogous structures, where "self-love" propels individuals toward mutual dependence rather than isolated anarchy.[57] In Epistle III, Pope applied this to politics and social relations, portraying the universe as "one system" of interconnected society mirroring divine order, with governments arising to enforce hierarchies that curb innate selfishness. He favored rule by natural superiors—the wise and virtuous—over egalitarian experiments, observing that "Forms of Government" succeed when aligned with inherent inequalities, as "Whate'er is best administered is best," prioritizing functional hierarchy over ideological uniformity.[60] This stance reflected Pope's empirical realism, drawn from historical precedents where rigid orders preserved civility against the "rude" equality of primitive states, though he acknowledged corruption could pervert even sound structures.[61] Critics later deemed such views regressive for resisting meritocratic flux, yet Pope grounded them in observable causal chains: hierarchy fosters coordination, while its erosion invites factional strife, as evidenced in contemporary English upheavals.[62]Critique of Modernity and Progressivism

Pope's satire targeted the intellectual pretensions and cultural shifts of early modern England, particularly the erosion of classical standards by commercialism and superficial innovation. In An Essay on Criticism (1711), he derided modern critics who reject the ancients they once emulated, likening them to "'pothecaries" who "taught the art" only to wield it against their masters, emphasizing that true judgment derives from humble adherence to established rules rather than presumptuous novelty.[63] This reflects his broader neoclassical insistence on imitating antiquity's proven forms over unchecked experimentation, which he saw as breeding disorder in poetry and criticism.[61] The Dunciad (1728, expanded 1742–1743) extended this critique to the burgeoning literary marketplace, portraying the goddess Dulness enthroning "dunces"—mediocre writers, journalists, and publishers—as harbingers of cultural decline. Pope lambasted Grub Street's hack productions and the rise of ephemeral print culture, which prioritized quantity and popularity over merit, foreseeing a "flood" of ignorance submerging taste and learning in London's fog-shrouded chaos.[42][41] Through mock-epic grandeur, he indicted modern education's emphasis on rote pedantry and sensationalism, arguing it fostered dullness triumphant over wit and order.[64] In An Essay on Man (1733–1734), Pope philosophically countered progressive faith in human perfectibility, positing a divinely ordained "Great Chain of Being" where each rank serves the whole, and disruptions via rational hubris yield only partial, misguided reforms. The dictum "Whatever is, is right" underscores acceptance of hierarchical reality over utopian reconfiguration, implicitly rebuking Enlightenment optimism that presumed reason could supplant tradition or providence. His Tory allegiance reinforced this, viewing Whig-era commercial expansion and social flux as corrosive to moral and aesthetic stability, favoring instead the enduring verities of nature and antiquity.[65]Religious Temperament and Deism Debunked

Alexander Pope was born on May 21, 1688, to devout Roman Catholic parents in London, a context marked by severe anti-Catholic legislation following the Glorious Revolution, which dethroned the Catholic King James II and imposed restrictions barring Catholics from public office, education, and residence near London.[15] Despite these Penal Laws, Pope adhered to Catholicism throughout his life, educating himself privately after being denied access to Protestant schools and universities, and his family relocated to Windsor Forest to comply with residency prohibitions.[1] His father, a linen merchant who retired early to avoid commerce tainted by Protestant associations, exemplified this commitment by converting substantial assets into property to evade inheritance taxes targeting Catholic estates.[15] Pope's religious practice remained consistent with Catholic orthodoxy; he received the last sacraments on his deathbed on May 30, 1744, affirming lifelong fidelity amid biographical accounts portraying him as a man of "religious temper," though not ostentatiously devout in public due to legal perils.[66] Early works like the 1712 eclogue Messiah explicitly drew on Christian prophecy from Isaiah, rendering messianic themes in pastoral verse to celebrate Christ's advent, countering secular literary trends with sacred intent.[66] Such compositions reflect a temperament rooted in revealed religion rather than rationalist abstraction, as Pope navigated England's confessional hostilities that rendered open Catholic devotion risky, yet he never apostatized despite incentives from Whig patronage networks favoring Protestant conformity. Claims of Deism in Pope's worldview, often inferred from the optimistic cosmology in An Essay on Man (1733–1734), misalign with his corpus and biography; the poem's theodicy, echoing Milton's justification of divine ways amid evil, presupposes human fallenness and the necessity of salvation through grace, incompatible with Deism's rejection of revelation and miracles.[67] Pope explicitly satirized Deist figures—Anthony Collins, Bernard Mandeville, and Thomas Woolston—in The Dunciad (1728, expanded 1742–1743), portraying their freethinking as dullness corrupting learning and piety, thereby defending hierarchical order under providential Christianity against mechanistic irreligion.[68] While Essay on Man's emphasis on partial knowledge and cosmic harmony invited Deist readings by contemporaries like Voltaire, who praised its "optimism" yet overlooked its Christian anthropology of original sin, Pope's intent—as gleaned from correspondence and revisions under Bolingbroke's influence, which he moderated toward orthodoxy—vindicated a personal God active in creation, not the absentee clockmaker of Deism.[62] Biographers attributing Deist leanings, such as those citing Pope's aversion to "theological dogmatism," conflate his poetic advocacy for "simple piety" with rejection of ecclesiastical forms, ignoring his sustained Catholic identity amid empirical pressures that would have eased via public recantation—none of which occurred.[69] Causal analysis reveals no doctrinal shift: Pope's satires targeted enthusiasm and skepticism alike, preserving a balanced Anglican-Catholic synthesis tolerant of mystery yet anchored in scripture and tradition, debunking Deist ascriptions as projections from Enlightenment biases favoring rationalism over confessional fidelity.[68] His temperament thus embodied resilient orthodoxy, prioritizing empirical adherence to inherited faith over fashionable irreligion.Satire, Feuds, and Controversies

Targets and Methods of Satire

Pope's satires primarily targeted the follies of contemporary society and the mediocrity of literary production, using his verse to dissect vanity, dullness, and cultural decline with surgical precision. In works such as The Rape of the Lock (initially published in two cantos in 1712 and expanded to five in 1714), he lampooned the aristocratic obsession with superficiality and honor, exemplified by the real-life quarrel between Arabella Fermor, whose lock of hair was severed by Lord Petre in 1711, and the ensuing family rift.[1] This incident served as a microcosm for broader critiques of elite society's disproportionate emphasis on trivial disputes over genuine moral or intellectual pursuits.[70] In The Dunciad (first published in three books in 1728, with revisions in 1729 and a fourth book added in 1742), Pope shifted focus to literary and intellectual targets, portraying an "empire of dullness" ruled by inept writers, critics, and publishers whom he branded as "dunces." Specific individuals included Lewis Theobald, the original "king of the dunces" in early editions for his Shakespeare editions and attacks on Pope; Colley Cibber, substituted in 1743 as poet laureate and emblem of tasteless populism; and figures like John Dennis, Laurence Eusden, and bookseller Edmund Curll, derided for plagiarism, bombast, and commercial exploitation of lowbrow culture.[1] [42] These attacks extended to broader groups, such as Grub Street hacks and Whig propagandists, whom Pope held responsible for eroding classical standards of wit and reason in favor of irrationality and misrule.[42] Pope's methods blended Horatian lightness with Juvenalian severity, employing the mock-epic form to inflate absurd subjects with the grandeur of classical models like Homer and Virgil, thereby exposing their inherent ridiculousness through contrast.[1] He wielded heroic couplets—closed, rhymed iambic pentameter lines—for their capacity to deliver epigrammatic wit via antithesis, zeugma, and unexpected turns, as in The Rape of the Lock's supernatural interventions (sylphs guarding Belinda) that parody epic divine machinery while highlighting human vanity.[1] In The Dunciad, techniques included burlesque games mimicking Olympic contests but devoted to nonsense, allegorical imagery of owls and crabs symbolizing stupidity and retreat, and self-parodic variorum footnotes that mimicked scholarly editions to mock the pedantry of his targets.[42] Irony and hyperbole amplified personal allusions, transforming satire into a weapon that not only ridiculed but also defended neoclassical ideals of order against encroaching chaos.[1]Literary Enemies and Personal Attacks

Pope's satirical writings frequently featured personal attacks on literary rivals, critics, and public figures he deemed emblematic of cultural decline, blending professional critique with barbed characterizations of their vices, appearances, and motivations. In The Dunciad (1728, expanded 1742–1743), he cataloged over a hundred "dunces"—hack writers, publishers, and poets—through exhaustive footnotes that exposed their failings, such as plagiarism, incompetence, and venality.[71] These assaults, often anonymous or veiled in allegory, provoked retaliations but solidified Pope's role as a defender of poetic merit against mediocrity.[71] A key target was Joseph Addison, with whom Pope initially collaborated on Cato (1713) and shared Whig literary circles. Tensions escalated during Pope's Iliad translation (1715–1720), when Addison's associates promoted Thomas Tickell's rival version, fueling Pope's suspicions of sabotage. In Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot (1735), Pope depicted Addison as "Atticus" (lines 193–214), a once-admired essayist turned "judge severe" whose subtle malice "wounds with a touch that's scarcely felt or seen, / Till scorch'd to nighest nothing," critiquing his pride and clique-driven infallibility.[72][73] Colley Cibber, appointed Poet Laureate in 1730 despite his comedic plays and perceived literary lightness, embodied for Pope the triumph of dullness over genius. Pope elevated him to "hero" in the 1743 Dunciad edition, replacing earlier protagonist Lewis Theobald and portraying Cibber as enthroned by the Goddess Dulness to rule over hackneyed verse. Cibber countered in A Letter from Mr. Cibber to Mr. Pope (1742), mocking Pope's "little spiteful heart" and physical frailty while defending his own public success as evidence against duncehood.[74][71] Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, an early correspondent and possible romantic interest, became "Sappho" in Pope's satires after their friendship fractured around 1722, amid mutual accusations of plagiarism and betrayal. In Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot (lines 89–96), Pope alluded to her indifference and lampooning habits, while earlier verses (1727) implied moral laxity; The Dunciad further coded her as a promiscuous figure. Montagu retaliated with anonymous verses ridiculing Pope's deformities and unrequited advances.[71] Other attacks included Lord John Hervey as "Sporus" in Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot (lines 305–333), a "painted child of dirt" evoking effeminacy and courtly servility, and critic John Dennis, whom Pope lampooned as early as 1708 for hypocritical taste. These feuds, rooted in rivalries over patronage and standards, invited personal barbs—enemies assailed Pope's hunchback and Catholicism—yet his verses prioritized exposing what he saw as intellectual corruption over mere revenge.[71][72]Responses to Critics and Unauthorized Publications

Pope frequently countered literary detractors through satirical verse rather than direct rebuttals, incorporating their attacks into works that amplified his defense while ridiculing their motives.[32] In 1711, following the publication of An Essay on Criticism, playwright and critic John Dennis lambasted the poem as derivative and Pope personally for his physical deformities, stemming from a perceived slight in the essay referencing Dennis's unsuccessful tragedy Appius and Virginia.[75] Pope retaliated indirectly by portraying Dennis as a "false critic" in subsequent satires, including the 1728 Dunciad, where Dennis appears as a champion of dullness, his rants on "enthusiasm" twisted to exemplify pedantic folly.[76] This approach exemplified Pope's strategy of transforming personal animosities into broader critiques of intellectual pretension, evidenced by Dennis's repeated public assaults from 1711 to 1717, which Pope absorbed into his evolving canon without stooping to prose polemics.[77] The publisher Edmund Curll posed a distinct threat through unauthorized editions and fabrications, prompting Pope's rare recourse to legal measures. Curll, notorious for pirating works and issuing spurious content, released an illicit collection of Pope's private letters in March 1735, obtained via forgery and theft from associates, which distorted Pope's views and fueled scandals.[78] In response, Pope swiftly compiled and published an authorized edition of his correspondence in June 1737, selectively editing letters to preserve his reputation and philosophical consistency, thereby preempting further distortions.[79] Curll's provocations extended to satirical pamphlets against Pope, including fake deathbed confessions, which Pope lampooned in the 1728 Dunciad as emblematic of Grub Street hackery.[80] The culmination of Pope's feud with Curll occurred in the 1741 lawsuit Pope v. Curll, where Pope sought an injunction against Curll's publication of the stolen letters, arguing that authors retained perpetual property rights over their writings irrespective of manuscript ownership.[81] The Court of Chancery granted a temporary injunction on March 4, 1741, recognizing letters as literary compositions subject to the author's control, a ruling that advanced perpetual copyright principles for unpublished works, though it did not fully resolve ownership of copies held by recipients.[82] This legal victory underscored Pope's vigilance against commercial exploitation, contrasting his satirical responses to critics with assertive protection of his intellectual output amid an era of lax publishing ethics.[83]Later Years

Twickenham Period and Health Decline

In 1719, following the death of his father, Alexander Pope relocated to Twickenham, a village west of London along the Thames, where he leased riverside properties from local landowner Thomas Vernon and resided for the remainder of his life.[84] He acquired a modest villa on five acres of land, which he progressively enlarged and adorned with terraced gardens descending to the river, incorporating classical landscaping principles influenced by his studies of antiquity.[85] Central to the estate was Pope's Grotto, constructed around 1720 as a tunnel under the adjacent road linking the villa to the Thames; designed as a nymphaeum—a decorative imitation cavern—it featured shells, minerals, and mirrors to create optical illusions and served as a repository for curiosities, reflecting Pope's aesthetic and intellectual pursuits.[86] Pope's mother, Edith, accompanied him to Twickenham and lived with him until her death on June 7, 1733, at age 93; the period was marked by frequent visits from literary friends including Jonathan Swift, John Gay, and members of the Scriblerus Club, fostering a hub of intellectual exchange amid his ongoing satirical and philosophical writings.[19] Despite this social vibrancy, Pope's health, compromised since childhood by spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease), which stunted his growth to approximately 4 feet 6 inches and caused chronic pain and deformity, began a marked decline in his later Twickenham years.[1] [9] Respiratory difficulties, asthma, and abdominal issues exacerbated by his tubercular infection intensified, compounded by high fevers and progressive frailty that confined him increasingly to his home.[13] In his final years, signs of heart failure emerged, likely precipitated by long-term pulmonary strain, leading to his death on May 30, 1744, at age 56; contemporaries noted his reliance on opiates for pain management, though the precise terminal event involved acute respiratory failure.[13] [87]Final Works and Death

In the early 1740s, Pope focused on completing and refining his satirical masterpiece, The Dunciad. He added a fourth book in 1742 and published the final edition in four books in October 1743, presenting a comprehensive assault on literary dullness and cultural decay, with Colley Cibber recast as the hero of dulness.[1][3] This edition included extensive notes and revisions, solidifying the poem's structure as a mock-epic prophecy of intellectual decline.[1] Pope also undertook revisions of his earlier works, preparing materials for a collected edition of his poetry, though he did not live to see it finalized. His output diminished due to intensifying health issues, including chronic respiratory problems and the effects of lifelong spinal tuberculosis that had stunted his growth and caused persistent pain.[1][3] Pope died on May 30, 1744, at his villa in Twickenham, aged 56, succumbing to dropsy (edema) and acute asthma amid his ongoing physical frailties.[1] He was buried in the garden of St. Mary's Church, Twickenham, with an epitaph he composed: "Here rests Sir Alexander Pope, Knight of the Holy Roman Empire."[3] His friend William Warburton later edited and published the collected works, incorporating Pope's final revisions.[1]Reception and Legacy

Contemporary Acclaim and Enemies

Pope's early works, including An Essay on Criticism (1711), garnered widespread acclaim for their wit, precision, and defense of neoclassical principles, establishing him as a preeminent poet by his early twenties.[1] The poem's maxims, such as "A little learning is a dangerous thing," circulated broadly in literary circles, influencing critics and poets alike for their encapsulation of taste and judgment.[88] His translations of Homer's Iliad (1715–1720) and Odyssey (1725–1726) achieved commercial triumph, netting him approximately £8,000—equivalent to over a million pounds today—through subscription models that drew support from aristocracy and intellectuals, affirming his status as a cultural arbiter.[89] Admirers included luminaries of the Scriblerus Club, such as Jonathan Swift, John Gay, John Arbuthnot, and Thomas Parnell, who valued his satirical acuity and Tory-aligned critiques of corruption; Swift, in particular, praised Pope's moral incisiveness in private correspondence, viewing him as a kindred spirit in combating intellectual dullness.[90] This acclaim coexisted with fierce enmities fueled by Pope's unsparing satires, which targeted publishers, critics, and hacks he deemed threats to literary standards. The Dunciad (1728, expanded 1742–1743) crowned Colley Cibber as "king of dunces" and excoriated figures like Lewis Theobald for shoddy scholarship, provoking retaliatory pamphlets and legal threats that intensified personal vendettas.[42] Enemies exploited Pope's physical deformities—resulting from childhood tuberculosis, leaving him hunchbacked and frail—to mock him viciously; Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Lord Hervey co-authored Verses Addressed to the Imitator of Horace (1733), deriding him as a "spider" and "hump," while Cibber capitalized on the feud for publicity.[91] Such attacks, often from Whig-aligned writers resentful of his Tory sympathies and independence, underscored a polarized reception: Pope's partisans hailed his defenses of meritocracy, but detractors, numbering in the dozens of published rebuttals, accused him of malice and elitism, amplifying his isolation despite patronage from figures like Bolingbroke.[92] This duality—veneration for his craft alongside vilification for his combats—defined his era's literary landscape, where personal animosities intertwined with aesthetic debates.[90]Romantic-Era Decline and Biases