Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alveolar process

View on Wikipedia

| Alveolar process | |

|---|---|

Anterior (frontal) part of maxilla (white) and mandible (orange) cut away towards right (to depth of tooth roots, i.e. the alveolar region) | |

| Details | |

| System | Skeletal |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os alveolaris |

| MeSH | D000539 |

| TA98 | A02.1.12.035 |

| TA2 | 791 |

| FMA | 59487 52897, 59487 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The alveolar process (/ælˈviːələr, ˌælviˈoʊlər, ˈælviələr/)[1] is the portion of bone containing the tooth sockets on the jaw bones (in humans, the maxilla and the mandible). The alveolar process is covered by gums within the mouth, terminating roughly along the line of the mandibular canal. Partially comprising compact bone, it is penetrated by many small openings for blood vessels and connective fibres.

The bone is of clinical, phonetic and forensic significance.

Terminology

[edit]The term alveolar (/ælˈviːələr/) ('hollow') refers to the cavities of the tooth sockets, known as dental alveoli.[2] The alveolar process is also called the alveolar bone or alveolar ridge.[3]

In phonetics, the term refers more specifically to the ridges on the inside of the mouth which can be felt with the tongue, either on roof of the mouth between the upper teeth and the hard palate or on the bottom of the mouth behind the lower teeth.[4]

The curved portion of the process is referred to as the alveolar arch.[5] The alveolar bone proper, also called bundle bone, directly surrounds the teeth.[6]

The terms alveolar border, alveolar crest, and alveolar margin describe the extreme rim of the bone nearest to the crowns of the teeth.[7][8][9]

The part of alveolar bone between two adjacent teeth is known as the interdental septum (or interdental bone).The connected, supporting area of the jaw (delineated by the apexes of the roots of the teeth) is known as the basal bone.[10]

Structure

[edit]

On the maxilla, the alveolar process is a ridge on the inferior surface, making up the thickest part of the bone. On the mandible it is a ridge on the superior surface. The structures hold the teeth and are encased by gums as part of the oral cavity.[11] The alveolar process comprises cells and periosteum, also encompassing nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels.The alveolar crest terminates uniformly at about the neck of the teeth (within about 1 to 2 millimetres in a healthy specimen), while the alveolar process terminates along the line of the mandibular canal.[12]

The alveolar process proper encases the tooth sockets, and contains a lining of compact bone around the roots of the teeth, called the lamina dura. This is attached by the periodontal ligament (PDL) to the root cementum. Although the alveolar process is composed of compact bone, it may be called the cribriform plate because it contains numerous openings known as Volkmann's canals, which allow blood vessels to pass between the alveolar bone and the PDL. The alveolar bone proper is also called bundle bone because Sharpey fibers, part of the PDL, are inserted there. Sharpey fibers in alveolar bone proper are inserted at a right angle (just as with the cemental surface); they are fewer in number, but thicker in diameter than those found in cementum.[13]

The supporting alveolar bone consists of both cortical (compact) bone and trabecular bone. The cortical bone consists of plates on the facial and lingual surfaces of the alveolar bone. These cortical plates are usually about 1.5 to 3 mm thick over posterior teeth, but the thickness is highly variable around anterior teeth. The trabecular bone consists of cancellous bone that is located between the alveolar bone proper and the cortical plates.[14]

The alveolar structure is a dynamic tissue which provides the jawbone with some degree of flexibility and resilience for the embedded teeth as they encounter numerous multi-directional forces.[15][16]

Composition

[edit]Alveolar bone is 67% inorganic material, composed mainly of the minerals calcium and phosphate. The mineral salts it contains are mostly in the form of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals.[17] The remaining alveolar bone (33%) is organic material, consisting of 28% collagen (mostly type I) and 5% non-collagenous protein.[17]

The cellular component of bone consists of osteoblasts, osteocytes and osteoclasts.[17]

Clinical significance

[edit]Alveolar bone loss

[edit]

Bone is lost through the process of resorption which involves osteoclasts breaking down the hard tissue of bone. A key indication of resorption is when scalloped erosion occurs. This is also known as Howship's lacuna.[18] The resorption phase lasts as long as the lifespan of the osteoclast which is around 8 to 10 days. After this resorption phase, the osteoclast can continue resorbing surfaces in another cycle or carry out apoptosis. A repair phase follows the resorption phase which lasts over 3 months. In patients with periodontal disease, inflammation lasts longer and during the repair phase, resorption may override any bone formation. This results in a net loss of alveolar bone.[19]

Alveolar bone loss is closely associated with periodontal disease. Periodontal disease involves the inflammation of the gingiva or gums or gingivitis. Studies in osteoimmunology have proposed 2 models for alveolar bone loss. One model states that inflammation is triggered by a periodontal pathogen which activates the acquired immune system to inhibit bone coupling by limiting new bone formation after resorption.[20] Another model states that cytokinesis may inhibit the differentiation of osteoblasts from their precursors, therefore limiting bone formation. This results in a net loss of alveolar bone.[21]

Developmental disturbances

[edit]The developmental disturbance of anodontia (or hypodontia, if only one tooth), in which tooth germs are congenitally absent, may affect the development of the alveolar processes. This occurrence can prevent the alveolar processes of either the maxillae or the mandible from developing. Proper development is impossible because the alveolar unit of each dental arch must form in response to the tooth germs in the area.[22]

Pathology

[edit]After extraction of a tooth, the clot in the alveolus fills in with immature bone, which later is remodeled into mature secondary bone. Disturbance of the blood clot can cause alveolar osteitis, commonly referred to as "dry socket". With the partial or total loss of teeth, the alveolar process undergoes resorption. The underlying basal bone of the body of the maxilla or mandible remains less affected, however, because it does not need the presence of teeth to remain viable. The loss of alveolar bone, coupled with attrition of the teeth, causes a loss of height of the lower third of the vertical dimension of the face when the teeth are in maximum intercuspation. The extent of this loss is determined based on clinical judgment using the Golden Proportions.[23]

The density of the alveolar bone in a given area also determines the route that dental infection takes with abscess formation, as well as the efficacy of local infiltration during the use of local anesthesia. In addition, the differences in alveolar process density determine the easiest and most convenient areas of bony fracture to be used, if needed during tooth extraction of impacted teeth. During chronic periodontal disease that has affected the periodontium (periodontitis), localized bone tissue is also lost. The radiographic integrity of the lamina dura is important in detecting pathologic lesions. It appears uniformly radiopaque (or lighter).[24]

Alveolar bone grafting

[edit]

Alveolar bone grafting in the mixed dentition is an essential part of the reconstructive journey for cleft lip and cleft palate patients. The reconstruction of the alveolar cleft can provide both aesthetic and practical advantages to the patient.[25] Alveolar bone grafting can also bring about the following benefits: stabilisation of the maxillary arch; aid of eruption of the canine and sometimes lateral incisor eruption; offering bony support to the teeth lying next to the cleft; elevate the alar base of the nose; aid sealing of oro-nasal fistula; permit insertion of a titanium fixture in the grafted region and achieve good periodontal conditions within and next to the cleft.[26] The timing of the alveolar bone grafting takes into consideration both eruption of the canine and lateral incisor. The optimal time for bone grafting surgery is when a thin shell of bone still covers the soon erupting lateral incisor or canine tooth close to the cleft.[26]

- Primary bone grafting: Primary bone grafting is believed to: eliminate bone deficiency, stabilize pre-maxilla, synthesize new bone matrix for eruption of teeth in the cleft area and augment the alar base. However, the early bone grafting procedure is abandoned in most cleft lip and palate centres around the world due to many disadvantages, including serious growth disturbances of the middle third of the facial skeleton. The operative technique that involves the vomero-premaxillary suture was found to inhibit maxillary growth.[26]

- Secondary bone grafting: Secondary bone grafting, also referred to as bone grafting in the mixed dentition, became a well-established procedure after abandoning primary bone grafting. The prerequisites include precise timing, operating technique, and acceptably vascularized soft tissue. The advantages of primary bone grafting, which are allowing tooth eruption through the grafted bone, are retained. Furthermore, secondary bone grafting stabilizes the maxillary arch, thus enhancing the conditions for prosthodontic treatment such as crowns, bridges and implants. It also aids eruption of teeth, boosting the amount of bony tissue on the alveolar crest, permitting orthodontic treatment. Bony support to teeth adjacent to the cleft is a pre-requisite for orthodontic closure of the teeth in the cleft region. Hence, better hygienic conditions will be achieved which helps to lessen formation of caries and periodontal inflammation. Speech problems caused by irregular positioning of articulators, or leakage of air via the oronasal communication, may also be improved. Secondary bone grafting can also be used to augment the alar base of the nose to achieve symmetry with the non-cleft side, thereby enhancing facial appearance.[26]

- Late secondary bone grafting: Bone grafting has a lower success rate when performed after canine has erupted as compared to before the eruption. It has been found that the possibility for orthodontic closure of the cleft in the dental arch is smaller in patients grafted before canine eruption than those after the canine eruption. The surgical procedure includes drilling of several small openings through the cortical layer into the cancellous layer, facilitating growth of blood vessels into the graft.[26]

Congenital epulis

[edit]Congenital epulis is a rare, benign mesenchymal tumour which usually presents at birth.[citation needed] It can be found growing on the alveolar ridge of newborns, presenting as non-ulcerated, pedunculated, reddish pink masses of varying sizes and numbers.[27] Congenital epulis can occur in either of the alveolar ridges, but they are found three times more frequently on the maxillary alveolar ridge than on the mandibular alveolar ridge. They also more commonly present in females compared to males.[27]

Dentistry

[edit]

The alveolar ridge is an area of particular interest in dentistry, as preservation of the ridges results in a higher success rate of therapeutic dental treatments.[28]

Grafting materials

[edit]Grafting is an effective technique to reduce the inevitable changes in dimension of the alveolar ridge after tooth extraction.[29] The type of grafting material is important as different materials are more effective than others in maintaining the alveolar ridge.[30]

No biomaterial can prevent alveolar bone loss entirely after extraction, however, there are five grafting materials with the greatest efficacy in height resorption prevention; three of which are xenograft materials (Gen-Os, Apatos, and MP3), one a platelet concentrate (A-PRF) and one composed of A-PRF and the allograft material AlloOss combined.[31][30]

For the best outcomes with respect to horizontal alveolar ridge preservation, application of a xenogenic (non-living bone material from another species) or allogenic grafting material (bone donated by another human) surrounded by a resorbable collagen membrane or sponge is ideal.[32] These membranes promote wound healing, osteogenesis and have a high biocompatibility.[33] Other reliable options for surgeons may include Bio-Oss and Bio-Oss Coll, primarily due to the strong scientific evidence behind their efficacy and recorded successful outcomes particularly in lateral ridge augmentation surgery.[30] L-PRF is also preferred in many clinical situations because of its low cost of preparation.[30]

Dental implants

[edit]

As the rate of tooth loss in the population increases either due to early extraction, trauma, or other systemic diseases, the use of implant therapy has increased as a form of tooth replacement therapy.[29][34] Dental implants are a way to replace missing teeth, as they consist of a titanium surgical component that is placed in the alveolar ridge of the jawbone.[35] The implant then acts as a prosthetic device that can hold either a crown, bridge, or denture on its external surface.[35] For the implant placement to be successful, there needs to be enough alveolar bone to support and stabilize the dental implant.[35] It has been determined that many factors can contribute to the loss of both the vertical and horizontal height of the alveolar bone.[36] These factors can include resorption of the bone after tooth removal (affecting the quality and quantity of the bone), the presence of periodontal disease, the age and gender of the patient, smoking habits, the presence of other systemic diseases, and oral hygiene habits.[37] Although dental implants tend to have a high success rate, of about 99%,[38] studies show that if an implant were to fail, it occurs more often in the front portion of the upper jaw.[39] More research is required to determine why this occurs, but it has been theorized that the alveolar bone in the upper jaw has a thinner cortical plate and lower bone density than that of the lower jaw.[39] As bone loss in the alveolar ridge becomes an increasing problem for the success of dental implants, research has been focused on the development of new surgical techniques and biomaterials that can be used to either maintain current bone levels, or to stimulate the growth of new alveolar bone through osteogenesis.[40][41][42]

Articulation

[edit]Consonants whose constriction is made with the tongue tip or blade touching or reaching for the alveolar ridge are called alveolar consonants. Examples of alveolar consonants in English are, for instance, [t], [d], [s], [z], [n], [l] like in the words tight, dawn, silly, zoo, nasty and lurid. There are exceptions to this however, such as speakers of the New York accent who pronounce [t] and [d] at the back of their top teeth (dental stops). When pronouncing these sounds the tongue touches ([t], [d], [n]), or nearly touches ([s], [z]) the upper alveolar ridge, which can also be referred to as gum ridge. In many other languages, consonants transcribed with these letters are articulated slightly differently, and are often described as dental consonants. In many languages consonants are articulated with the tongue touching or close to the upper alveolar ridge. The former are called alveolar plosives (such as [t] and [d]), and the latter alveolar fricatives (such as [s] and [ʃ]) or (such as [z] and [ʒ]).

In culture

[edit]Other than a maxillar bridge made of gold, part of a mandible with teeth—which had been burned and broken around the alveolar process—was the only physical evidence used to confirm Adolf Hitler's death in 1945. Historians such as Anton Joachimsthaler assert that the remainder of the body was burnt to near-ashes,[43][44][45] but this is scientifically doubtful.[46][47][48] Additionally, according to a purported Soviet autopsy report, the alveolar process was missing from the charred maxilla of the body presumed to belong to Eva Braun.[49]

Gallery

[edit]-

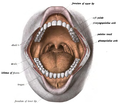

In the oral cavity, the alveolar processes are covered by gums.

-

How the roots of the teeth, gums, and alveolar bone are related

-

3D animation showing placement of teeth in human skull

-

Hitler's mandibular remains were sundered at the alveolar process.

-

Eroded alveolar process of the archaic human Homo heidelbergensis

References

[edit]- ^ Wells JC (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 9781405881180.

- ^ "alveolar | Origin and meaning of alveolar". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 198

- ^ Phonetics at the Encyclopædia Britannica Accessed: 12 September 2018.

- ^ Sazonova, O.; Vovk, O.; Hordiichuk, D.; Ikramov, V. (February 2019). "Anatomical Features Of The Maxillary Alveolar Arch In Adulthood". Georgian Medical News (287): 111–114. ISSN 1512-0112. PMID 30958300.

- ^ Araujo M, Lindhe J (2003). "The Edentulous Alveolar Ridge.". In Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang NP (eds.). Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry (5th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard. pp. 53–63.

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 199

- ^ "Alveolar border". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "margin". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 199-202

- ^ Walker, William B. (1990), Walker, H. Kenneth; Hall, W. Dallas; Hurst, J. Willis (eds.), "The Oral Cavity and Associated Structures", Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.), Boston: Butterworths, ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4, PMID 21250078, retrieved 30 August 2021

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 199

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 207

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 198-202

- ^ Monje A, Chan HL, Galindo-Moreno P, Elnayef B, Suarez-Lopez del Amo F, Wang F, Wang HL (November 2015). "Alveolar Bone Architecture: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Periodontology. 86 (11): 1231–1248. doi:10.1902/jop.2015.150263. hdl:2027.42/141748. PMID 26177631.

- ^ MacBeth N, Trullenque-Eriksson A, Donos N, Mardas N (August 2017). "Hard and soft tissue changes following alveolar ridge preservation: a systematic review". Clinical Oral Implants Research. 28 (8): 982–1004. doi:10.1111/clr.12911. PMID 27458031. S2CID 27295301.

- ^ a b c Bathla, Shalu (2017). Textbook of Periodontics (1st ed.). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-9386261731. OCLC 971599883.

- ^ Bar-Shavit Z (December 2007). "The osteoclast: a multinucleated, hematopoietic-origin, bone-resorbing osteoimmune cell". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 102 (5): 1130–9. doi:10.1002/jcb.21553. PMID 17955494. S2CID 21096888.

- ^ Philias R, Garant PR (2003). Oral cells and tissues. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0867154290. OCLC 51892824.

- ^ Leone CW, Bokhadhoor H, Kuo D, Desta T, Yang J, Siqueira MF, et al. (April 2006). "Immunization enhances inflammation and tissue destruction in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis". Infection and Immunity. 74 (4): 2286–92. doi:10.1128/IAI.74.4.2286-2292.2006. PMC 1418897. PMID 16552059.

- ^ Graves DT, Li J, Cochran DL (February 2011). "Inflammation and uncoupling as mechanisms of periodontal bone loss". Journal of Dental Research. 90 (2): 143–53. doi:10.1177/0022034510385236. PMC 3144100. PMID 21135192.

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 199

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 203-204

- ^ Fehrenbach and Popowics, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Elsevier, 2026, page 199

- ^ Coots BK (November 2012). "Alveolar bone grafting: past, present, and new horizons". Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 26 (4): 178–83. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333887. PMC 3706037. PMID 24179451.

- ^ a b c d e Lilja J (October 2009). "Alveolar bone grafting". Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 42 Suppl (3): S110-5. doi:10.4103/0970-0358.57200. PMC 2825060. PMID 19884665.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons License.

- ^ a b Gan J, Shi C, Liu S, Tian X, Wang X, Ma X, Gao P (May 2021). "Multiple congenital granular cell tumours of the maxilla and mandible: a rare case report and review of the literature". Translational Pediatrics. 10 (5): 1386–1392. doi:10.21037/tp-21-32. PMC 8192993. PMID 34189098.

- ^ Willenbacher M, Al-Nawas B, Berres M, Kämmerer PW, Schiegnitz E (December 2016). "The Effects of Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Meta-Analysis". Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research. 18 (6): 1248–1268. doi:10.1111/cid.12364. PMID 26132885.

- ^ a b Avila-Ortiz G, Elangovan S, Kramer KW, Blanchette D, Dawson DV (October 2014). "Effect of alveolar ridge preservation after tooth extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Dental Research. 93 (10): 950–958. doi:10.1177/0022034514541127. PMC 4293706. PMID 24966231.

- ^ a b c d Canellas JV, Soares BN, Ritto FG, Vettore MV, Vidigal Júnior GM, Fischer RG, Medeiros PJ (November 2021). "What grafting materials produce greater alveolar ridge preservation after tooth extraction? A systematic review and network meta-analysis". Journal of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 49 (11): 1064–1071. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2021.06.005. hdl:11250/3134049. PMID 34176715. S2CID 235659457.

- ^ Stumbras A, Kuliesius P, Januzis G, Juodzbalys G (January 2019). "Alveolar Ridge Preservation after Tooth Extraction Using Different Bone Graft Materials and Autologous Platelet Concentrates: a Systematic Review". Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Research. 10 (1): e2. doi:10.5037/jomr.2019.10102. PMC 6498816. PMID 31069040.

- ^ Avila-Ortiz G, Chambrone L, Vignoletti F (June 2019). "Effect of alveolar ridge preservation interventions following tooth extraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 46 (Suppl 21): 195–223. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13057. PMID 30623987. S2CID 58649044.

- ^ Sbricoli L, Guazzo R, Annunziata M, Gobbato L, Bressan E, Nastri L (February 2020). "Selection of Collagen Membranes for Bone Regeneration: A Literature Review". Materials. 13 (3): 786. Bibcode:2020Mate...13..786S. doi:10.3390/ma13030786. PMC 7040903. PMID 32050433.

- ^ Khalifa AK, Wada M, Ikebe K, Maeda Y (December 2016). "To what extent residual alveolar ridge can be preserved by implant? A systematic review". International Journal of Implant Dentistry. 2 (1) 22. doi:10.1186/s40729-016-0057-z. PMC 5120622. PMID 27878769.

- ^ a b c Motamedian SR, Khojaste M, Khojasteh A (January–June 2016). "Success rate of implants placed in autogenous bone blocks versus allogenic bone blocks: A systematic literature review". Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery. 6 (1): 78–90. doi:10.4103/2231-0746.186143. PMC 4979349. PMID 27563613.

- ^ Zhang X, Li Y, Ge Z, Zhao H, Miao L, Pan Y (January 2020). "The dimension and morphology of alveolar bone at maxillary anterior teeth in periodontitis: a retrospective analysis-using CBCT". International Journal of Oral Science. 12 (1) 4. doi:10.1038/s41368-019-0071-0. PMC 6957679. PMID 31932579.

- ^ Kuć J, Sierpińska T, Gołębiewska M (2017). "Alveolar ridge atrophy related to facial morphology in edentulous patients". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 12: 1481–1494. doi:10.2147/CIA.S140791. PMC 5602450. PMID 28979109.

- ^ Makowiecki A, Hadzik J, Błaszczyszyn A, Gedrange T, Dominiak M (May 2019). "An evaluation of superhydrophilic surfaces of dental implants - a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Oral Health. 19 (1) 79. doi:10.1186/s12903-019-0767-8. PMC 6509828. PMID 31077190.

- ^ a b Fouda AA (June 2020). "The impact of the alveolar bone sites on early implant failure: a systematic review with meta-analysis". Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 46 (3): 162–173. doi:10.5125/jkaoms.2020.46.3.162. PMC 7338630. PMID 32606277.

- ^ Pérez-Sayáns M, Martínez-Martín JM, Chamorro-Petronacci C, Gallas-Torreira M, Marichalar-Mendía X, García-García A (November 2018). "20 years of alveolar distraction: A systematic review of the literature". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 23 (6): e742 – e751. doi:10.4317/medoral.22645. PMC 6261008. PMID 30341270.

- ^ Strauss FJ, Stähli A, Gruber R (October 2018). "The use of platelet-rich fibrin to enhance the outcomes of implant therapy: A systematic review". Clinical Oral Implants Research. 29 (Suppl 18): 6–19. doi:10.1111/clr.13275. PMC 6221166. PMID 30306698.

- ^ Keestra JA, Barry O, Jong L, Wahl G (2016). "Long-term effects of vertical bone augmentation: a systematic review". Journal of Applied Oral Science. 24 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1590/1678-775720150357. PMC 4775004. PMID 27008252.

- ^ Joachimsthaler, Anton (1998) [1996]. The Last Days of Hitler. London: Arms & Armour Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-85409-465-0.

- ^ Bezymenski, Lev (1968). The Death of Adolf Hitler (1st ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. p. 45.

- ^ Charlier, Philippe; Weil, Raphael; Rainsard, P.; Poupon, Joël; Brisard, J.C. (1 May 2018). "The remains of Adolf Hitler: A biomedical analysis and definitive identification". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 54: e10 – e12. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2018.05.014. PMID 29779904. S2CID 29159362.

- ^ Benecke, Mark (12 December 2022) [2003]. "The Hunt for Hitler's Teeth". Bizarre. Retrieved 4 March 2024 – via Dr. Mark Benecke.

- ^ Castillo, Rafael Fernández; Ubelaker, Douglas H.; Acosta, José Antonio Lorente; Cañadas de la Fuente, Guillermo A. (10 March 2013). "Effects of temperature on bone tissue. Histological study of the changes in the bone matrix". Forensic Science International. 226 (1): 33–37. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.11.012. hdl:10481/91826. ISSN 0379-0738.

- ^ Thompson, Tim; Gowland, Rebecca. "What Happens to Human Bodies When They Are Burned?". Durham University. Retrieved 9 May 2024 – via FutureLearn.

- ^ Bezymenski, Lev (1968). The Death of Adolf Hitler (1st ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. p. 111.

Sources

[edit]- Fehrenbach, MJ; Popowics, T (2026). Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy. Elsevier. ISBN 9780443104244.

External links

[edit]- Photo of model at Waynesburg College skeleton/alveolarprocess

- "Anatomy diagram: 34256.000-1". Roche Lexicon – illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012.

- Diagram at case.edu