Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ant colony optimization algorithms

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In computer science and operations research, the ant colony optimization algorithm (ACO) is a probabilistic technique for solving computational problems that can be reduced to finding good paths through graphs. Artificial ants represent multi-agent methods inspired by the behavior of real ants. The pheromone-based communication of biological ants is often the predominant paradigm used.[2] Combinations of artificial ants and local search algorithms have become a preferred method for numerous optimization tasks involving some sort of graph, e.g., vehicle routing and internet routing.

As an example, ant colony optimization[3] is a class of optimization algorithms modeled on the actions of an ant colony.[4] Artificial 'ants' (e.g. simulation agents) locate optimal solutions by moving through a parameter space representing all possible solutions. Real ants lay down pheromones to direct each other to resources while exploring their environment. The simulated 'ants' similarly record their positions and the quality of their solutions, so that in later simulation iterations more ants locate better solutions.[5] One variation on this approach is the bees algorithm, which is more analogous to the foraging patterns of the honey bee, another social insect.

This algorithm is a member of the ant colony algorithms family, in swarm intelligence methods, and it constitutes some metaheuristic optimizations. Initially proposed by Marco Dorigo in 1992 in his PhD thesis,[6][7] the first algorithm was aiming to search for an optimal path in a graph, based on the behavior of ants seeking a path between their colony and a source of food. The original idea has since diversified to solve a wider class of numerical problems, and as a result, several problems have emerged, drawing on various aspects of the behavior of ants. From a broader perspective, ACO performs a model-based search[8] and shares some similarities with estimation of distribution algorithms.

Overview

[edit]In the natural world, ants of some species (initially) wander randomly, and upon finding food return to their colony while laying down pheromone trails. If other ants find such a path, they are likely to stop travelling at random and instead follow the trail, returning and reinforcing it if they eventually find food (see Ant communication).[9]

Over time, however, the pheromone trail starts to evaporate, thus reducing its attractive strength. The more time it takes for an ant to travel down the path and back again, the more time the pheromones have to evaporate. A short path, by comparison, is marched over more frequently, and thus the pheromone density becomes higher on shorter paths than longer ones. Pheromone evaporation also has the advantage of avoiding the convergence to a locally optimal solution. If there were no evaporation at all, the paths chosen by the first ants would tend to be excessively attractive to the following ones. In that case, the exploration of the solution space would be constrained. The influence of pheromone evaporation in real ant systems is unclear, but it is very important in artificial systems.[10]

The overall result is that when one ant finds a good (i.e., short) path from the colony to a food source, other ants are more likely to follow that path, and positive feedback eventually leads to many ants following a single path. The idea of the ant colony algorithm is to mimic this behavior with "simulated ants" walking around the graph representing the problem to be solved.

Ambient networks of intelligent objects

[edit]New concepts are required since "intelligence" is no longer centralized but can be found throughout all minuscule objects. Anthropocentric concepts have been known to lead to the production of IT systems in which data processing, control units and calculating power are centralized. These centralized units have continually increased their performance and can be compared to the human brain. The model of the brain has become the ultimate vision of computers. Ambient networks of intelligent objects and, sooner or later, a new generation of information systems that are even more diffused and based on nanotechnology, will profoundly change this concept. Small devices that can be compared to insects do not possess a high intelligence on their own. Indeed, their intelligence can be classed as fairly limited. It is, for example, impossible to integrate a high performance calculator with the power to solve any kind of mathematical problem into a biochip that is implanted into the human body or integrated in an intelligent tag designed to trace commercial articles. However, once those objects are interconnected they develop a form of intelligence that can be compared to a colony of ants or bees. In the case of certain problems, this type of intelligence can be superior to the reasoning of a centralized system similar to the brain.[11]

Nature offers several examples of how minuscule organisms, if they all follow the same basic rule, can create a form of collective intelligence on the macroscopic level. Colonies of social insects perfectly illustrate this model which greatly differs from human societies. This model is based on the cooperation of independent units with simple and unpredictable behavior.[12] They move through their surrounding area to carry out certain tasks and only possess a very limited amount of information to do so. A colony of ants, for example, represents numerous qualities that can also be applied to a network of ambient objects. Colonies of ants have a very high capacity to adapt themselves to changes in the environment, as well as great strength in dealing with situations where one individual fails to carry out a given task. This kind of flexibility would also be very useful for mobile networks of objects which are perpetually developing. Parcels of information that move from a computer to a digital object behave in the same way as ants would do. They move through the network and pass from one node to the next with the objective of arriving at their final destination as quickly as possible.[13]

Artificial pheromone system

[edit]Pheromone-based communication is one of the most effective ways of communication which is widely observed in nature. Pheromone is used by social insects such as bees, ants and termites; both for inter-agent and agent-swarm communications. Due to its feasibility, artificial pheromones have been adopted in multi-robot and swarm robotic systems. Pheromone-based communication was implemented by different means such as chemical [14][15][16] or physical (RFID tags,[17] light,[18][19][20][21] sound[22]) ways. However, those implementations were not able to replicate all the aspects of pheromones as seen in nature.

Using projected light was presented in a 2007 IEEE paper by Garnier, Simon, et al. as an experimental setup to study pheromone-based communication with micro autonomous robots.[23] Another study presented a system in which pheromones were implemented via a horizontal LCD screen on which the robots moved, with the robots having downward facing light sensors to register the patterns beneath them.[24][25]

Algorithm and formula

[edit]In the ant colony optimization algorithms, an artificial ant is a simple computational agent that searches for good solutions to a given optimization problem. To apply an ant colony algorithm, the optimization problem needs to be converted into the problem of finding the shortest path on a weighted graph. In the first step of each iteration, each ant stochastically constructs a solution, i.e. the order in which the edges in the graph should be followed. In the second step, the paths found by the different ants are compared. The last step consists of updating the pheromone levels on each edge.

procedure ACO_MetaHeuristic is

while not terminated do

generateSolutions()

daemonActions()

pheromoneUpdate()

repeat

end procedure

Edge selection

[edit]Each ant needs to construct a solution to move through the graph. To select the next edge in its tour, an ant will consider the length of each edge available from its current position, as well as the corresponding pheromone level. At each step of the algorithm, each ant moves from a state to state , corresponding to a more complete intermediate solution. Thus, each ant computes a set of feasible expansions to its current state in each iteration, and moves to one of these in probability. For ant , the probability of moving from state to state depends on the combination of two values, the attractiveness of the move, as computed by some heuristic indicating the a priori desirability of that move and the trail level of the move, indicating how proficient it has been in the past to make that particular move. The trail level represents a posteriori indication of the desirability of that move.

In general, the th ant moves from state to state with probability

where is the amount of pheromone deposited for transition from state to , ≥ 0 is a parameter to control the influence of , is the desirability of state transition (a priori knowledge, typically , where is the distance) and ≥ 1 is a parameter to control the influence of . and represent the trail level and attractiveness for the other possible state transitions.

Pheromone update

[edit]Trails are usually updated when all ants have completed their solution, increasing or decreasing the level of trails corresponding to moves that were part of "good" or "bad" solutions, respectively. An example of a global pheromone updating rule is now

where is the amount of pheromone deposited for a state transition , is the pheromone evaporation coefficient, is the number of ants and is the amount of pheromone deposited by th ant, typically given for a TSP problem (with moves corresponding to arcs of the graph) by

where is the cost of the th ant's tour (typically length) and is a constant.

Common extensions

[edit]Here are some of the most popular variations of ACO algorithms.

Ant system (AS)

[edit]The ant system is the first ACO algorithm. This algorithm corresponds to the one presented above. It was developed by Dorigo.[26]

Ant colony system (ACS)

[edit]In the ant colony system algorithm, the original ant system was modified in three aspects:

- The edge selection is biased towards exploitation (i.e. favoring the probability of selecting the shortest edges with a large amount of pheromone);

- While building a solution, ants change the pheromone level of the edges they are selecting by applying a local pheromone updating rule;

- At the end of each iteration, only the best ant is allowed to update the trails by applying a modified global pheromone updating rule.[27]

Elitist ant system

[edit]In this algorithm, the global best solution deposits pheromone on its trail after every iteration (even if this trail has not been revisited), along with all the other ants. The elitist strategy has as its objective directing the search of all ants to construct a solution to contain links of the current best route.

Max-min ant system (MMAS)

[edit]This algorithm controls the maximum and minimum pheromone amounts on each trail. Only the global best tour or the iteration best tour are allowed to add pheromone to its trail. To avoid stagnation of the search algorithm, the range of possible pheromone amounts on each trail is limited to an interval [τmax,τmin]. All edges are initialized to τmax to force a higher exploration of solutions. The trails are reinitialized to τmax when nearing stagnation.[28]

Rank-based ant system (ASrank)

[edit]All solutions are ranked according to their length. Only a fixed number of the best ants in this iteration are allowed to update their trials. The amount of pheromone deposited is weighted for each solution, such that solutions with shorter paths deposit more pheromone than the solutions with longer paths.

Parallel ant colony optimization (PACO)

[edit]An ant colony system (ACS) with communication strategies is developed. The artificial ants are partitioned into several groups. Seven communication methods for updating the pheromone level between groups in ACS are proposed and work on the traveling salesman problem. [29]

Continuous orthogonal ant colony (COAC)

[edit]The pheromone deposit mechanism of COAC is to enable ants to search for solutions collaboratively and effectively. By using an orthogonal design method, ants in the feasible domain can explore their chosen regions rapidly and efficiently, with enhanced global search capability and accuracy. The orthogonal design method and the adaptive radius adjustment method can also be extended to other optimization algorithms for delivering wider advantages in solving practical problems.[30]

Recursive ant colony optimization

[edit]It is a recursive form of ant system which divides the whole search domain into several sub-domains and solves the objective on these subdomains.[31] The results from all the subdomains are compared and the best few of them are promoted for the next level. The subdomains corresponding to the selected results are further subdivided and the process is repeated until an output of desired precision is obtained. This method has been tested on ill-posed geophysical inversion problems and works well.[32]

Convergence

[edit]For some versions of the algorithm, it is possible to prove that it is convergent (i.e., it is able to find the global optimum in finite time). The first evidence of convergence for an ant colony algorithm was made in 2000, the graph-based ant system algorithm, and later on for the ACS and MMAS algorithms. Like most metaheuristics, it is very difficult to estimate the theoretical speed of convergence. A performance analysis of a continuous ant colony algorithm with respect to its various parameters (edge selection strategy, distance measure metric, and pheromone evaporation rate) showed that its performance and rate of convergence are sensitive to the chosen parameter values, and especially to the value of the pheromone evaporation rate.[33] In 2004, Zlochin and his colleagues[8] showed that ACO-type algorithms are closely related to stochastic gradient descent, Cross-entropy method and estimation of distribution algorithm. They proposed an umbrella term "Model-based search" to describe this class of metaheuristics.

Applications

[edit]

Ant colony optimization algorithms have been applied to many combinatorial optimization problems, ranging from quadratic assignment to protein folding or routing vehicles and a lot of derived methods have been adapted to dynamic problems in real variables, stochastic problems, multi-targets and parallel implementations. It has also been used to produce near-optimal solutions to the travelling salesman problem. They have an advantage over simulated annealing and genetic algorithm approaches of similar problems when the graph may change dynamically; the ant colony algorithm can be run continuously and adapt to changes in real time. This is of interest in network routing and urban transportation systems.

The first ACO algorithm was called the ant system[26] and it was aimed to solve the travelling salesman problem, in which the goal is to find the shortest round-trip to link a series of cities. The general algorithm is relatively simple and based on a set of ants, each making one of the possible round-trips along the cities. At each stage, the ant chooses to move from one city to another according to some rules:

- It must visit each city exactly once;

- A distant city has less chance of being chosen (the visibility);

- The more intense the pheromone trail laid out on an edge between two cities, the greater the probability that that edge will be chosen;

- Having completed its journey, the ant deposits more pheromones on all edges it traversed, if the journey is short;

- After each iteration, trails of pheromones evaporate.

Scheduling problem

[edit]- Sequential ordering problem (SOP) [34]

- Job-shop scheduling problem (JSP)[35]

- Open-shop scheduling problem (OSP)[36][37]

- Permutation flow shop problem (PFSP)[38]

- Single machine total tardiness problem (SMTTP)[39]

- Single machine total weighted tardiness problem (SMTWTP)[40][41][42]

- Resource-constrained project scheduling problem (RCPSP)[43]

- Group-shop scheduling problem (GSP)[44]

- Single-machine total tardiness problem with sequence dependent setup times (SMTTPDST)[45]

- Multistage flowshop scheduling problem (MFSP) with sequence dependent setup/changeover times[46]

- Assembly sequence planning (ASP) problems[47]

Vehicle routing problem

[edit]- Capacitated vehicle routing problem (CVRP)[48][49][50]

- Multi-depot vehicle routing problem (MDVRP)[51]

- Period vehicle routing problem (PVRP)[52]

- Split delivery vehicle routing problem (SDVRP)[53]

- Stochastic vehicle routing problem (SVRP)[54]

- Vehicle routing problem with pick-up and delivery (VRPPD)[55][56]

- Vehicle routing problem with time windows (VRPTW)[57][58][59][60]

- Time dependent vehicle routing problem with time windows (TDVRPTW)[61]

- Vehicle routing problem with time windows and multiple service workers (VRPTWMS)

Assignment problem

[edit]- Quadratic assignment problem (QAP)[62]

- Generalized assignment problem (GAP)[63][64]

- Frequency assignment problem (FAP)[65]

- Redundancy allocation problem (RAP)[66]

Set problem

[edit]- Set cover problem (SCP)[67][68]

- Partition problem (SPP)[69]

- Weight constrained graph tree partition problem (WCGTPP)[70]

- Arc-weighted l-cardinality tree problem (AWlCTP)[71]

- Multiple knapsack problem (MKP)[72]

- Maximum independent set problem (MIS)[73]

Device sizing problem in nanoelectronics physical design

[edit]- Ant colony optimization (ACO) based optimization of 45 nm CMOS-based sense amplifier circuit could converge to optimal solutions in very minimal time.[74]

- Ant colony optimization (ACO) based reversible circuit synthesis could improve efficiency significantly.[75]

Antennas optimization and synthesis

[edit]

To optimize the form of antennas, ant colony algorithms can be used. As example can be considered antennas RFID-tags based on ant colony algorithms (ACO),[77] loopback and unloopback vibrators 10×10[76]

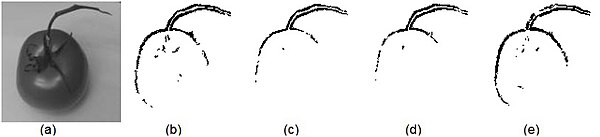

Image processing

[edit]The ACO algorithm is used in image processing for image edge detection and edge linking.[78][79]

- Edge detection:

The graph here is the 2-D image and the ants traverse from one pixel depositing pheromone. The movement of ants from one pixel to another is directed by the local variation of the image's intensity values. This movement causes the highest density of the pheromone to be deposited at the edges.

The following are the steps involved in edge detection using ACO:[80][81][82]

Step 1: Initialization. Randomly place ants on the image where . Pheromone matrix are initialized with a random value. The major challenge in the initialization process is determining the heuristic matrix.

There are various methods to determine the heuristic matrix. For the below example the heuristic matrix was calculated based on the local statistics: the local statistics at the pixel position .

where is the image of size ,

is a normalization factor, and

can be calculated using the following functions:

The parameter in each of above functions adjusts the functions' respective shapes.

Step 2: Construction process. The ant's movement is based on 4-connected pixels or 8-connected pixels. The probability with which the ant moves is given by the probability equation

Step 3 and step 5: Update process. The pheromone matrix is updated twice. in step 3 the trail of the ant (given by ) is updated where as in step 5 the evaporation rate of the trail is updated which is given by:

- ,

where is the pheromone decay coefficient

Step 7: Decision process. Once the K ants have moved a fixed distance L for N iteration, the decision whether it is an edge or not is based on the threshold T on the pheromone matrix τ. Threshold for the below example is calculated based on Otsu's method.

Image edge detected using ACO: The images below are generated using different functions given by the equation (1) to (4).[83]

- Edge linking:[84] ACO has also proven effective in edge linking algorithms.

Other applications

[edit]- Bankruptcy prediction[85]

- Classification[35]

- Connection-oriented network routing[86]

- Connectionless network routing[87][88]

- Data mining[35][89][90][91]

- Discounted cash flows in project scheduling[92]

- Distributed information retrieval[93][94]

- Energy and electricity network design[95]

- Grid workflow scheduling problem[96]

- Inhibitory peptide design for protein protein interactions[97]

- Intelligent testing system[98]

- Power electronic circuit design[99]

- Protein folding[100][101][102]

- System identification[103][104]

Definition difficulty

[edit]

With an ACO algorithm, the shortest path in a graph, between two points A and B, is built from a combination of several paths.[105] It is not easy to give a precise definition of what algorithm is or is not an ant colony, because the definition may vary according to the authors and uses. Broadly speaking, ant colony algorithms are regarded as populated metaheuristics with each solution represented by an ant moving in the search space.[106] Ants mark the best solutions and take account of previous markings to optimize their search. They can be seen as probabilistic multi-agent algorithms using a probability distribution to make the transition between each iteration.[107] In their versions for combinatorial problems, they use an iterative construction of solutions.[108] According to some authors, the thing which distinguishes ACO algorithms from other relatives (such as algorithms to estimate the distribution or particle swarm optimization) is precisely their constructive aspect. In combinatorial problems, it is possible that the best solution eventually be found, even though no ant would prove effective. Thus, in the example of the travelling salesman problem, it is not necessary that an ant actually travels the shortest route: the shortest route can be built from the strongest segments of the best solutions. However, this definition can be problematic in the case of problems in real variables, where no structure of 'neighbours' exists. The collective behaviour of social insects remains a source of inspiration for researchers. The wide variety of algorithms (for optimization or not) seeking self-organization in biological systems has led to the concept of "swarm intelligence",[11] which is a very general framework in which ant colony algorithms fit.

Stigmergy algorithms

[edit]There is in practice a large number of algorithms claiming to be "ant colonies", without always sharing the general framework of optimization by canonical ant colonies.[109] In practice, the use of an exchange of information between ants via the environment (a principle called "stigmergy") is deemed enough for an algorithm to belong to the class of ant colony algorithms. This principle has led some authors to create the term "value" to organize methods and behavior based on search of food, sorting larvae, division of labour and cooperative transportation.[110]

Related methods

[edit]- Genetic algorithms (GA)

- These maintain a pool of solutions rather than just one. The process of finding superior solutions mimics that of evolution, with solutions being combined or mutated to alter the pool of solutions, with solutions of inferior quality being discarded.

- Estimation of distribution algorithm (EDA)

- An evolutionary algorithm that substitutes traditional reproduction operators by model-guided operators. Such models are learned from the population by employing machine learning techniques and represented as probabilistic graphical models, from which new solutions can be sampled[111][112] or generated from guided-crossover.[113][114]

- Simulated annealing (SA)

- A related global optimization technique which traverses the search space by generating neighboring solutions of the current solution. A superior neighbor is always accepted. An inferior neighbor is accepted probabilistically based on the difference in quality and a temperature parameter. The temperature parameter is modified as the algorithm progresses to alter the nature of the search.

- Reactive search optimization

- Focuses on combining machine learning with optimization, by adding an internal feedback loop to self-tune the free parameters of an algorithm to the characteristics of the problem, of the instance, and of the local situation around the current solution.

- Tabu search (TS)

- Similar to simulated annealing in that both traverse the solution space by testing mutations of an individual solution. While simulated annealing generates only one mutated solution, tabu search generates many mutated solutions and moves to the solution with the lowest fitness of those generated. To prevent cycling and encourage greater movement through the solution space, a tabu list is maintained of partial or complete solutions. It is forbidden to move to a solution that contains elements of the tabu list, which is updated as the solution traverses the solution space.

- Artificial immune system (AIS)

- Modeled on vertebrate immune systems.

- Particle swarm optimization (PSO)

- A swarm intelligence method.

- Intelligent water drops (IWD)

- A swarm-based optimization algorithm based on natural water drops flowing in rivers

- Gravitational search algorithm (GSA)

- A swarm intelligence method.

- Ant colony clustering method (ACCM)

- A method that make use of clustering approach, extending the ACO.

- Stochastic diffusion search (SDS)

- An agent-based probabilistic global search and optimization technique best suited to problems where the objective function can be decomposed into multiple independent partial-functions.

History

[edit]

Chronology of ant colony optimization algorithms.

- 1959, Pierre-Paul Grassé invented the theory of stigmergy to explain the behavior of nest building in termites;[115]

- 1983, Deneubourg and his colleagues studied the collective behavior of ants;[116]

- 1988, and Moyson Manderick have an article on self-organization among ants;[117]

- 1989, the work of Goss, Aron, Deneubourg and Pasteels on the collective behavior of Argentine ants, which will give the idea of ant colony optimization algorithms;[118]

- 1989, implementation of a model of behavior for food by Ebling and his colleagues;[119]

- 1991, M. Dorigo proposed the ant system in his doctoral thesis (which was published in 1992[7]). A technical report extracted from the thesis and co-authored by V. Maniezzo and A. Colorni[120] was published five years later;[26]

- 1994, Appleby and Steward of British Telecommunications Plc published the first application to telecommunications networks[121]

- 1995, Gambardella and Dorigo proposed ant-q,[122] the preliminary version of ant colony system as first extension of ant system;.[26]

- 1996, Gambardella and Dorigo proposed ant colony system [123]

- 1996, publication of the article on ant system;[26]

- 1997, Dorigo and Gambardella proposed ant colony system hybridized with local search;[27]

- 1997, Schoonderwoerd and his colleagues published an improved application to telecommunication networks;[124]

- 1998, Dorigo launches first conference dedicated to the ACO algorithms;[125]

- 1998, Stützle proposes initial parallel implementations;[126]

- 1999, Gambardella, Taillard and Agazzi proposed macs-vrptw, first multi ant colony system applied to vehicle routing problems with time windows,[57]

- 1999, Bonabeau, Dorigo and Theraulaz publish a book dealing mainly with artificial ants[127]

- 2000, special issue of the Future Generation Computer Systems journal on ant algorithms[128]

- 2000, Hoos and Stützle invent the max-min ant system;[28]

- 2000, first applications to the scheduling, scheduling sequence and the satisfaction of constraints;

- 2000, Gutjahr provides the first evidence of convergence for an algorithm of ant colonies[129]

- 2001, the first use of COA algorithms by companies (Eurobios and AntOptima);

- 2001, Iredi and his colleagues published the first multi-objective algorithm[130]

- 2002, first applications in the design of schedule, Bayesian networks;

- 2002, Bianchi and her colleagues suggested the first algorithm for stochastic problem;[131]

- 2004, Dorigo and Stützle publish the Ant Colony Optimization book with MIT Press [132]

- 2004, Zlochin and Dorigo show that some algorithms are equivalent to the stochastic gradient descent, the cross-entropy method and algorithms to estimate distribution[8]

- 2005, first applications to protein folding problems.

- 2012, Prabhakar and colleagues publish research relating to the operation of individual ants communicating in tandem without pheromones, mirroring the principles of computer network organization. The communication model has been compared to the Transmission Control Protocol.[133]

- 2016, first application to peptide sequence design.[97]

- 2017, successful integration of the multi-criteria decision-making method PROMETHEE into the ACO algorithm (HUMANT algorithm).[134]

References

[edit]- ^ Waldner, Jean-Baptiste (2008). Nanocomputers and Swarm Intelligence. London: ISTE John Wiley & Sons. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-84704-002-2.

- ^ Monmarché Nicolas; Guinand Frédéric; Siarry Patrick (2010). Artificial Ants. Wiley-ISTE. ISBN 978-1-84821-194-0.

- ^ M. Dorigo; L. M. Gambardella (1997). "Learning Approach to the Traveling Salesman Problem". IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation. 1 (1): 214. doi:10.1109/4235.585892.

- ^ Birattari, M.; Pellegrini, P.; Dorigo, M. (2007). "On the Invariance of Ant Colony Optimization". IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation. 11 (6). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): 732–742. doi:10.1109/tevc.2007.892762. ISSN 1941-0026. S2CID 1591891.

- ^ Ant Colony Optimization by Marco Dorigo and Thomas Stützle, MIT Press, 2004. ISBN 0-262-04219-3

- ^ A. Colorni, M. Dorigo et V. Maniezzo, Distributed Optimization by Ant Colonies, actes de la première conférence européenne sur la vie artificielle, Paris, France, Elsevier Publishing, 134-142, 1991.

- ^ a b M. Dorigo, Optimization, Learning and Natural Algorithms, PhD thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Italy, 1992.

- ^ a b c M. Zlochin, M. Birattari, N. Meuleau, et M. Dorigo, Model-based search for combinatorial optimization: A critical survey, Annals of Operations Research, vol. 131, pp. 373-395, 2004.

- ^ Fladerer, Johannes-Paul; Kurzmann, Ernst (November 2019). WISDOM OF THE MANY: how to create self -organisation and how to use collective... intelligence in companies and in society from mana. BOOKS ON DEMAND. ISBN 978-3-7504-2242-1.

- ^ Marco Dorigo and Thomas Stützle, Ant Colony Optimization, p.12. 2004.

- ^ a b Waldner, Jean-Baptiste (2008). Nanocomputers and Swarm Intelligence. London: ISTE John Wiley & Sons. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-84704-002-2.

- ^ Waldner, Jean-Baptiste (2007). Inventer l'Ordinateur du XXIème Siècle. London: Hermes Science. pp. 259–265. ISBN 978-2-7462-1516-0.

- ^ Waldner, Jean-Baptiste (2008). Nanocomputers and Swarm Intelligence. London: ISTE John Wiley & Sons. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-84704-002-2.

- ^ Lima, Danielli A., and Gina MB Oliveira. "A cellular automata ant memory model of foraging in a swarm of robots." Applied Mathematical Modelling 47, 2017: 551-572.

- ^ Russell, R. Andrew. "Ant trails-an example for robots to follow?." Robotics and Automation, 1999. Proceedings. 1999 IEEE International Conference on. Vol. 4. IEEE, 1999.

- ^ Fujisawa, Ryusuke, et al. "Designing pheromone communication in swarm robotics: Group foraging behavior mediated by chemical substance." Swarm Intelligence 8.3 (2014): 227-246.

- ^ Sakakibara, Toshiki, and Daisuke Kurabayashi. "Artificial pheromone system using rfid for navigation of autonomous robots." Journal of Bionic Engineering 4.4 (2007): 245-253.

- ^ Arvin, Farshad, et al. "Investigation of cue-based aggregation in static and dynamic environments with a mobile robot swarm." Adaptive Behavior (2016): 1-17.

- ^ Farshad Arvin, et al. "Imitation of honeybee aggregation with collective behavior of swarm robots." International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems 4.4 (2011): 739-748.

- ^ Schmickl, Thomas, et al. "Get in touch: cooperative decision making based on robot-to-robot collisions." Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 18.1 (2009): 133-155.

- ^ Garnier, Simon, et al. "Do ants need to estimate the geometrical properties of trail bifurcations to find an efficient route? A swarm robotics test bed." PLoS Comput Biol 9.3 (2013): e1002903.

- ^ Arvin, Farshad, et al. "Cue-based aggregation with a mobile robot swarm: a novel fuzzy-based method." Adaptive Behavior 22.3 (2014): 189-206.

- ^ Garnier, Simon, et al. "Alice in pheromone land: An experimental setup for the study of ant-like robots." 2007 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium. IEEE, 2007.

- ^ Farshad Arvin et al. "COSΦ: artificial pheromone system for robotic swarms research." IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 2015.

- ^ Krajník, Tomáš, et al. "A practical multirobot localization system Archived 2019-10-16 at the Wayback Machine." Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 76.3-4 (2014): 539-562.

- ^ a b c d e M. Dorigo, V. Maniezzo, et A. Colorni, Ant system: optimization by a colony of cooperating agents, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics--Part B, volume 26, numéro 1, pages 29-41, 1996.

- ^ a b M. Dorigo et L.M. Gambardella, Ant Colony System : A Cooperative Learning Approach to the Traveling Salesman Problem, IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, volume 1, numéro 1, pages 53-66, 1997.

- ^ a b T. Stützle et H.H. Hoos, MAX MIN Ant System, Future Generation Computer Systems, volume 16, pages 889-914, 2000

- ^ Chu S C, Roddick J F, Pan J S. Ant colony system with communication strategies[J]. Information sciences, 2004, 167(1-4): 63-76.

- ^ X Hu, J Zhang, and Y Li (2008). Orthogonal methods based ant colony search for solving continuous optimization problems. Journal of Computer Science and Technology, 23(1), pp.2-18.

- ^ Gupta, D.K.; Arora, Y.; Singh, U.K.; Gupta, J.P., "Recursive Ant Colony Optimization for estimation of parameters of a function", 1st International Conference on Recent Advances in Information Technology (RAIT), vol., no., pp. 448-454, 15–17 March 2012

- ^ Gupta, D.K.; Gupta, J.P.; Arora, Y.; Shankar, U., "Recursive ant colony optimization: a new technique for the estimation of function parameters from geophysical field data Archived 2019-12-21 at the Wayback Machine," Near Surface Geophysics, vol. 11, no. 3, pp.325-339

- ^ V.K.Ojha, A. Abraham and V. Snasel, ACO for Continuous Function Optimization: A Performance Analysis, 14th International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications (ISDA), Japan, Page 145 - 150, 2017, 978-1-4799-7938-7/14 2014 IEEE.

- ^ L.M. Gambardella, M. Dorigo, "An Ant Colony System Hybridized with a New Local Search for the Sequential Ordering Problem", INFORMS Journal on Computing, vol.12(3), pp. 237-255, 2000.

- ^ a b c D. Martens, M. De Backer, R. Haesen, J. Vanthienen, M. Snoeck, B. Baesens, Classification with Ant Colony Optimization, IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, volume 11, number 5, pages 651—665, 2007.

- ^ B. Pfahring, "Multi-agent search for open scheduling: adapting the Ant-Q formalism," Technical report TR-96-09, 1996.

- ^ C. Blem, "Beam-ACO, Hybridizing ant colony optimization with beam search. An application to open shop scheduling," Technical report TR/IRIDIA/2003-17, 2003.

- ^ T. Stützle, "An ant approach to the flow shop problem," Technical report AIDA-97-07, 1997.

- ^ A. Bauer, B. Bullnheimer, R. F. Hartl and C. Strauss, "Minimizing total tardiness on a single machine using ant colony optimization," Central European Journal for Operations Research and Economics, vol.8, no.2, pp.125-141, 2000.

- ^ M. den Besten, "Ants for the single machine total weighted tardiness problem," Master's thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2000.

- ^ M, den Bseten, T. Stützle and M. Dorigo, "Ant colony optimization for the total weighted tardiness problem," Proceedings of PPSN-VI, Sixth International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, vol. 1917 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp.611-620, 2000.

- ^ D. Merkle and M. Middendorf, "An ant algorithm with a new pheromone evaluation rule for total tardiness problems," Real World Applications of Evolutionary Computing, vol. 1803 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp.287-296, 2000.

- ^ D. Merkle, M. Middendorf and H. Schmeck, "Ant colony optimization for resource-constrained project scheduling," Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO 2000), pp.893-900, 2000.

- ^ C. Blum, "ACO applied to group shop scheduling: a case study on intensification and diversification[dead link]," Proceedings of ANTS 2002, vol. 2463 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp.14-27, 2002.

- ^ C. Gagné, W. L. Price and M. Gravel, "Comparing an ACO algorithm with other heuristics for the single machine scheduling problem with sequence-dependent setup times," Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol.53, pp.895-906, 2002.

- ^ A. V. Donati, V. Darley, B. Ramachandran, "An Ant-Bidding Algorithm for Multistage Flowshop Scheduling Problem: Optimization and Phase Transitions", book chapter in Advances in Metaheuristics for Hard Optimization, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-72959-4, pp.111-138, 2008.

- ^ Han, Z., Wang, Y. & Tian, D. Ant colony optimization for assembly sequence planning based on parameters optimization. Front. Mech. Eng. 16, 393–409 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11465-020-0613-3

- ^ Toth, Paolo; Vigo, Daniele (2002). "Models, relaxations and exact approaches for the capacitated vehicle routing problem". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 123 (1–3): 487–512. doi:10.1016/S0166-218X(01)00351-1.

- ^ J. M. Belenguer, and E. Benavent, "A cutting plane algorithm for capacitated arc routing problem," Computers & Operations Research, vol.30, no.5, pp.705-728, 2003.

- ^ T. K. Ralphs, "Parallel branch and cut for capacitated vehicle routing," Parallel Computing, vol.29, pp.607-629, 2003.

- ^ Salhi, S.; Sari, M. (1997). "A multi-level composite heuristic for the multi-depot vehicle fleet mix problem". European Journal of Operational Research. 103: 95–112. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(96)00253-6.

- ^ Angelelli, Enrico; Speranza, Maria Grazia (2002). "The periodic vehicle routing problem with intermediate facilities". European Journal of Operational Research. 137 (2): 233–247. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(01)00206-5.

- ^ Ho, Sin C.; Haugland, Dag (2002). "A Tabu Search Heuristic for the Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows and Split Deliveries". Computers and Operations Research. 31 (12): 1947–1964. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.8.7096. doi:10.1016/S0305-0548(03)00155-2.

- ^ Secomandi, Nicola. "Comparing neuro-dynamic programming algorithms for the vehicle routing problem with stochastic demands". Computers & Operations Research: 2000. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.392.4034.

- ^ W. P. Nanry and J. W. Barnes, "Solving the pickup and delivery problem with time windows using reactive tabu search," Transportation Research Part B, vol.34, no. 2, pp.107-121, 2000.

- ^ R. Bent and P.V. Hentenryck, "A two-stage hybrid algorithm for pickup and delivery vehicle routing problems with time windows," Computers & Operations Research, vol.33, no.4, pp.875-893, 2003.

- ^ a b L.M. Gambardella, E. Taillard, G. Agazzi, "MACS-VRPTW: A Multiple Ant Colony System for Vehicle Routing Problems with Time Windows", In D. Corne, M. Dorigo and F. Glover, editors, New Ideas in Optimization, McGraw-Hill, London, UK, pp. 63-76, 1999.

- ^ Bachem, A.; Hochstättler, W.; Malich, M. (1996). "The simulated trading heuristic for solving vehicle routing problems". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 65 (1–3): 47–72. doi:10.1016/0166-218X(95)00027-O.

- ^ Hong, Sung-Chul; Park, Yang-Byung (1999). "A heuristic for bi-objective vehicle routing with time window constraints". International Journal of Production Economics. 62 (3): 249–258. doi:10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00250-3.

- ^ Russell, Robert A.; Chiang, Wen-Chyuan (2006). "Scatter search for the vehicle routing problem with time windows". European Journal of Operational Research. 169 (2): 606–622. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2004.08.018.

- ^ A. V. Donati, R. Montemanni, N. Casagrande, A. E. Rizzoli, L. M. Gambardella, "Time Dependent Vehicle Routing Problem with a Multi Ant Colony System", European Journal of Operational Research, vol.185, no.3, pp.1174–1191, 2008.

- ^ Stützle, Thomas (1997). "MAX-MIN Ant System for Quadratic Assignment Problems". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.47.5167.

• Stützle, Thomas (July 1997). MAX-MIN Ant System for Quadratic Assignment Problems (Technical report). TU Darmstadt, Germany: FG Intellektik. AIDA–97–4. - ^ R. Lourenço and D. Serra "Adaptive search heuristics for the generalized assignment problem," Mathware & soft computing, vol.9, no.2-3, 2002.

- ^ M. Yagiura, T. Ibaraki and F. Glover, "An ejection chain approach for the generalized assignment problem," INFORMS Journal on Computing, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 133–151, 2004.

- ^ K. I. Aardal, S. P. M. van Hoesel, A. M. C. A. Koster, C. Mannino and Antonio. Sassano, "Models and solution techniques for the frequency assignment problem," A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research, vol.1, no.4, pp.261-317, 2001.

- ^ Y. C. Liang and A. E. Smith, "An ant colony optimization algorithm for the redundancy allocation problem (RAP)[permanent dead link]," IEEE Transactions on Reliability, vol.53, no.3, pp.417-423, 2004.

- ^ G. Leguizamon and Z. Michalewicz, "A new version of ant system for subset problems," Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation(CEC 99), vol.2, pp.1458-1464, 1999.

- ^ R. Hadji, M. Rahoual, E. Talbi and V. Bachelet "Ant colonies for the set covering problem," Abstract proceedings of ANTS2000, pp.63-66, 2000.

- ^ V Maniezzo and M Milandri, "An ant-based framework for very strongly constrained problems," Proceedings of ANTS2000, pp.222-227, 2002.

- ^ R. Cordone and F. Maffioli,"Colored Ant System and local search to design local telecommunication networks[dead link]," Applications of Evolutionary Computing: Proceedings of Evo Workshops, vol.2037, pp.60-69, 2001.

- ^ C. Blum and M.J. Blesa, "Metaheuristics for the edge-weighted k-cardinality tree problem," Technical Report TR/IRIDIA/2003-02, IRIDIA, 2003.

- ^ S. Fidanova, "ACO algorithm for MKP using various heuristic information", Numerical Methods and Applications, vol.2542, pp.438-444, 2003.

- ^ G. Leguizamon, Z. Michalewicz and Martin Schutz, "An ant system for the maximum independent set problem," Proceedings of the 2001 Argentinian Congress on Computer Science, vol.2, pp.1027-1040, 2001.

- ^ O. Okobiah, S. P. Mohanty, and E. Kougianos, "Ordinary Kriging Metamodel-Assisted Ant Colony Algorithm for Fast Analog Design Optimization Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine", in Proceedings of the 13th IEEE International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), pp. 458--463, 2012.

- ^ M. Sarkar, P. Ghosal, and S. P. Mohanty, "Reversible Circuit Synthesis Using ACO and SA based Quinne-McCluskey Method Archived July 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine", in Proceedings of the 56th IEEE International Midwest Symposium on Circuits & Systems (MWSCAS), 2013, pp. 416--419.

- ^ a b c Ermolaev S.Y., Slyusar V.I. Antenna synthesis based on the ant colony optimization algorithm.// Proc. ICATT'2009, Lviv, Ukraine 6 - 9 Octobre, 2009. - Pages 298 - 300 [1]

- ^ Marcus Randall, Andrew Lewis, Amir Galehdar, David Thiel. Using Ant Colony Optimisation to Improve the Efficiency of Small Meander Line RFID Antennas.// In 3rd IEEE International e-Science and Grid Computing Conference [2], 2007

- ^ S. Meshoul and M Batouche, "Ant colony system with extremal dynamics for point matching and pose estimation," Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, vol.3, pp.823-826, 2002.

- ^ H. Nezamabadi-pour, S. Saryazdi, and E. Rashedi, "Edge detection using ant algorithms", Soft Computing, vol. 10, no.7, pp. 623-628, 2006.

- ^ Tian, Jing; Yu, Weiyu; Xie, Shengli (2008). "An ant colony optimization algorithm for image edge detection". 2008 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence). pp. 751–756. doi:10.1109/CEC.2008.4630880. ISBN 978-1-4244-1822-0. S2CID 1782195.

- ^ Gupta, Charu; Gupta, Sunanda. "Edge Detection of an Image based on Ant ColonyOptimization Technique".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jevtić, A.; Quintanilla-Dominguez, J.; Cortina-Januchs, M.G.; Andina, D. (2009). "Edge detection using ant colony search algorithm and multiscale contrast enhancement". 2009 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics. pp. 2193–2198. doi:10.1109/ICSMC.2009.5345922. ISBN 978-1-4244-2793-2. S2CID 11654036.

- ^ "File Exchange – Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)". MATLAB Central. 21 July 2023.

- ^ Jevtić, A.; Melgar, I.; Andina, D. (2009). "Ant based edge linking algorithm". 2009 35th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics. 35th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics, 3–5 November 2009. IECON '09. pp. 3353–3358. doi:10.1109/IECON.2009.5415195. ISBN 978-1-4244-4648-3. S2CID 34664559.

- ^ Zhang, Y. (2013). "A Rule-Based Model for Bankruptcy Prediction Based on an Improved Genetic Ant Colony Algorithm". Mathematical Problems in Engineering. 2013 753251. doi:10.1155/2013/753251.

- ^ G. D. Caro and M. Dorigo, "Extending AntNet for best-effort quality-of-service routing," Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Ant Colony Optimization (ANTS'98), 1998.

- ^ G.D. Caro and M. Dorigo "AntNet: a mobile agents approach to adaptive routing[permanent dead link]," Proceedings of the Thirty-First Hawaii International Conference on System Science, vol.7, pp.74-83, 1998.

- ^ G. D. Caro and M. Dorigo, "Two ant colony algorithms for best-effort routing in datagram networks," Proceedings of the Tenth IASTED International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Computing and Systems (PDCS'98), pp.541-546, 1998.

- ^ D. Martens, B. Baesens, T. Fawcett "Editorial Survey: Swarm Intelligence for Data Mining," Machine Learning, volume 82, number 1, pp. 1-42, 2011

- ^ R. S. Parpinelli, H. S. Lopes and A. A Freitas, "An ant colony algorithm for classification rule discovery," Data Mining: A heuristic Approach, pp.191-209, 2002.

- ^ R. S. Parpinelli, H. S. Lopes and A. A Freitas, "Data mining with an ant colony optimization algorithm[dead link]," IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, vol.6, no.4, pp.321-332, 2002.

- ^ W. N. Chen, J. ZHANG and H. Chung, "Optimizing Discounted Cash Flows in Project Scheduling--An Ant Colony Optimization Approach", IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics--Part C: Applications and Reviews Vol.40 No.5 pp.64-77, Jan. 2010.

- ^ D. Picard, A. Revel, M. Cord, "An Application of Swarm Intelligence to Distributed Image Retrieval", Information Sciences, 2010

- ^ D. Picard, M. Cord, A. Revel, "Image Retrieval over Networks : Active Learning using Ant Algorithm", IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 1356--1365 - nov 2008

- ^ Warner, Lars; Vogel, Ute (2008). Optimization of energy supply networks using ant colony optimization (PDF). Environmental Informatics and Industrial Ecology — 22nd International Conference on Informatics for Environmental Protection. Aachen, Germany: Shaker Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8322-7313-2. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- ^ W. N. Chen and J. ZHANG "Ant Colony Optimization Approach to Grid Workflow Scheduling Problem with Various QoS Requirements", IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics--Part C: Applications and Reviews, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp.29-43, Jan 2009.

- ^ a b Zaidman, Daniel; Wolfson, Haim J. (2016-08-01). "PinaColada: peptide–inhibitor ant colony ad-hoc design algorithm". Bioinformatics. 32 (15): 2289–2296. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btw133. ISSN 1367-4803. PMID 27153578.

- ^ Xiao. M.Hu, J. ZHANG, and H. Chung, "An Intelligent Testing System Embedded with an Ant Colony Optimization Based Test Composition Method", IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics--Part C: Applications and Reviews, Vol. 39, No. 6, pp. 659-669, Dec 2009.

- ^ J. ZHANG, H. Chung, W. L. Lo, and T. Huang, "Extended Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm for Power Electronic Circuit Design", IEEE Transactions on Power Electronic. Vol. 24, No.1, pp.147-162, Jan 2009.

- ^ X. M. Hu, J. ZHANG, J. Xiao and Y. Li, "Protein Folding in Hydrophobic-Polar Lattice Model: A Flexible Ant- Colony Optimization Approach ", Protein and Peptide Letters, Volume 15, Number 5, 2008, Pp. 469-477.

- ^ A. Shmygelska, R. A. Hernández and H. H. Hoos, "An ant colony optimization algorithm for the 2D HP protein folding problem[dead link]," Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Ant Algorithms/ANTS 2002, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol.2463, pp.40-52, 2002.

- ^ M. Nardelli; L. Tedesco; A. Bechini (March 2013). "Cross-lattice behavior of general ACO folding for proteins in the HP model". SAC '13: Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing. pp. 1320–1327. doi:10.1145/2480362.2480611. ISBN 978-1-4503-1656-9. S2CID 1216890.

- ^ L. Wang and Q. D. Wu, "Linear system parameters identification based on ant system algorithm," Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Control Applications, pp. 401-406, 2001.

- ^ K. C. Abbaspour, R. Schulin, M. T. Van Genuchten, "Estimating unsaturated soil hydraulic parameters using ant colony optimization," Advances In Water Resources, vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 827-841, 2001.

- ^ Shmygelska, Alena; Hoos, Holger H. (2005). "An ant colony optimisation algorithm for the 2D and 3D hydrophobic polar protein folding problem". BMC Bioinformatics. 6: 30. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-6-30. PMC 555464. PMID 15710037.

- ^ Fred W. Glover, Gary A. Kochenberger, Handbook of Metaheuristics, [3], Springer (2003)

- ^ "Ciad-Lab |" (PDF).

- ^ WJ Gutjahr, ACO algorithms with guaranteed convergence to the optimal solution, [4][permanent dead link], (2002)

- ^ Santpal Singh Dhillon, Ant Routing, Searching and Topology Estimation Algorithms for Ad Hoc Networks, [5], IOS Press, (2008)

- ^ A. Ajith; G. Crina; R. Vitorino (éditeurs), Stigmergic Optimization, Studies in Computational Intelligence, volume 31, 299 pages, 2006. ISBN 978-3-540-34689-0

- ^ Pelikan, Martin; Goldberg, David E.; Cantú-Paz, Erick (July 1999). "BOA: The Bayesian Optimization Algorithm". GECCO'99: Proceedings of the 1st Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation - Volume 1. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. pp. 525–532. ISBN 978-1-55860-611-1.

- ^ Pelikan, Martin (2005). Hierarchical Bayesian optimization algorithm: toward a new generation of evolutionary algorithms (1st ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-23774-7.

- ^ Thierens, Dirk (11 September 2010). "The Linkage Tree Genetic Algorithm". Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, PPSN XI. pp. 264–273. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15844-5_27. ISBN 978-3-642-15843-8. S2CID 28648829.

- ^ Martins, Jean P.; Fonseca, Carlos M.; Delbem, Alexandre C. B. (25 December 2014). "On the performance of linkage-tree genetic algorithms for the multidimensional knapsack problem". Neurocomputing. 146: 17–29. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2014.04.069.

- ^ P.-P. Grassé, La reconstruction du nid et les coordinations inter-individuelles chez Belicositermes natalensis et Cubitermes sp. La théorie de la Stigmergie : Essai d'interprétation du comportement des termites constructeurs, Insectes Sociaux, numéro 6, p. 41-80, 1959.

- ^ J.L. Denebourg, J.M. Pasteels et J.C. Verhaeghe, Probabilistic Behaviour in Ants : a Strategy of Errors?, Journal of Theoretical Biology, numéro 105, 1983.

- ^ F. Moyson, B. Manderick, The collective behaviour of Ants : an Example of Self-Organization in Massive Parallelism, Actes de AAAI Spring Symposium on Parallel Models of Intelligence, Stanford, Californie, 1988.

- ^ S. Goss, S. Aron, J.-L. Deneubourg et J.-M. Pasteels, Self-organized shortcuts in the Argentine ant, Naturwissenschaften, volume 76, pages 579-581, 1989

- ^ M. Ebling, M. Di Loreto, M. Presley, F. Wieland, et D. Jefferson,An Ant Foraging Model Implemented on the Time Warp Operating System, Proceedings of the SCS Multiconference on Distributed Simulation, 1989

- ^ Dorigo M., V. Maniezzo et A. Colorni, Positive feedback as a search strategy, rapport technique numéro 91-016, Dip. Elettronica, Politecnico di Milano, Italy, 1991

- ^ Appleby, S. & Steward, S. Mobile software agents for control in telecommunications networks, BT Technol. J., 12(2):104–113, April 1994

- ^ L.M. Gambardella and M. Dorigo, "Ant-Q: a reinforcement learning approach to the traveling salesman problem", Proceedings of ML-95, Twelfth International Conference on Machine Learning, A. Prieditis and S. Russell (Eds.), Morgan Kaufmann, pp. 252–260, 1995

- ^ L.M. Gambardella and M. Dorigo, "Solving Symmetric and Asymmetric TSPs by Ant Colonies", Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Evolutionary Computation, ICEC96, Nagoya, Japan, May 20–22, pp. 622-627, 1996;

- ^ R. Schoonderwoerd, O. Holland, J. Bruten et L. Rothkrantz, Ant-based load balancing in telecommunication networks, Adaptive Behaviour, volume 5, numéro 2, pages 169-207, 1997

- ^ M. Dorigo, ANTS' 98, From Ant Colonies to Artificial Ants : First International Workshop on Ant Colony Optimization, ANTS 98, Bruxelles, Belgique, octobre 1998.

- ^ T. Stützle, Parallelization Strategies for Ant Colony Optimization, Proceedings of PPSN-V, Fifth International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, Springer-Verlag, volume 1498, pages 722-731, 1998.

- ^ É. Bonabeau, M. Dorigo et G. Theraulaz, Swarm intelligence, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- ^ M. Dorigo, G. Di Caro et T. Stützle, Special issue on "Ant Algorithms[dead link]", Future Generation Computer Systems, volume 16, numéro 8, 2000

- ^ W.J. Gutjahr, A graph-based Ant System and its convergence, Future Generation Computer Systems, volume 16, pages 873-888, 2000.

- ^ S. Iredi, D. Merkle et M. Middendorf, Bi-Criterion Optimization with Multi Colony Ant Algorithms, Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization, First International Conference (EMO'01), Zurich, Springer Verlag, pages 359-372, 2001.

- ^ L. Bianchi, L.M. Gambardella et M.Dorigo, An ant colony optimization approach to the probabilistic traveling salesman problem, PPSN-VII, Seventh International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer Verlag, Berlin, Allemagne, 2002.

- ^ M. Dorigo and T. Stützle, Ant Colony Optimization, MIT Press, 2004.

- ^ B. Prabhakar, K. N. Dektar, D. M. Gordon, "The regulation of ant colony foraging activity without spatial information ", PLOS Computational Biology, 2012. URL: http://www.ploscompbiol.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pcbi.1002670

- ^ Mladineo, Marko; Veza, Ivica; Gjeldum, Nikola (2017). "Solving partner selection problem in cyber-physical production networks using the HUMANT algorithm". International Journal of Production Research. 55 (9): 2506–2521. doi:10.1080/00207543.2016.1234084. S2CID 114390939.

Publications (selected)

[edit]- M. Dorigo, 1992. Optimization, Learning and Natural Algorithms, PhD thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Italy.

- M. Dorigo, V. Maniezzo & A. Colorni, 1996. "Ant System: Optimization by a Colony of Cooperating Agents", IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics–Part B, 26 (1): 29–41.

- M. Dorigo & L. M. Gambardella, 1997. "Ant Colony System: A Cooperative Learning Approach to the Traveling Salesman Problem". IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 1 (1): 53–66.

- M. Dorigo, G. Di Caro & L. M. Gambardella, 1999. "Ant Algorithms for Discrete Optimization Archived 2018-10-06 at the Wayback Machine". Artificial Life, 5 (2): 137–172.

- E. Bonabeau, M. Dorigo et G. Theraulaz, 1999. Swarm Intelligence: From Natural to Artificial Systems, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513159-2

- M. Dorigo & T. Stützle, 2004. Ant Colony Optimization, MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-04219-3

- M. Dorigo, 2007. "Ant Colony Optimization". Scholarpedia.

- C. Blum, 2005 "Ant colony optimization: Introduction and recent trends". Physics of Life Reviews, 2: 353-373

- M. Dorigo, M. Birattari & T. Stützle, 2006 Ant Colony Optimization: Artificial Ants as a Computational Intelligence Technique. TR/IRIDIA/2006-023

- Mohd Murtadha Mohamad,"Articulated Robots Motion Planning Using Foraging Ant Strategy", Journal of Information Technology - Special Issues in Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 20, No. 4 pp. 163–181, December 2008, ISSN 0128-3790.

- N. Monmarché, F. Guinand & P. Siarry (eds), "Artificial Ants", August 2010 Hardback 576 pp. ISBN 978-1-84821-194-0.

- A. Kazharov, V. Kureichik, 2010. "Ant colony optimization algorithms for solving transportation problems", Journal of Computer and Systems Sciences International, Vol. 49. No. 1. pp. 30–43.

- C-M. Pintea, 2014, Advances in Bio-inspired Computing for Combinatorial Optimization Problem, Springer ISBN 978-3-642-40178-7

- K. Saleem, N. Fisal, M. A. Baharudin, A. A. Ahmed, S. Hafizah and S. Kamilah, "Ant colony inspired self-optimized routing protocol based on cross layer architecture for wireless sensor networks", WSEAS Trans. Commun., vol. 9, no. 10, pp. 669–678, 2010. ISBN 978-960-474-200-4

- K. Saleem and N. Fisal, "Enhanced Ant Colony algorithm for self-optimized data assured routing in wireless sensor networks", Networks (ICON) 2012 18th IEEE International Conference on, pp. 422–427. ISBN 978-1-4673-4523-1

- Abolmaali S, Roodposhti FR. Portfolio Optimization Using Ant Colony Method a Case Study on Tehran Stock Exchange. Journal of Accounting. 2018 Mar;8(1).

External links

[edit]- Scholarpedia Ant Colony Optimization page

- Ant Colony Optimization Home Page

- "Ant Colony Optimization" - Russian scientific and research community

- AntSim - Simulation of Ant Colony Algorithms

- MIDACO-Solver General purpose optimization software based on ant colony optimization (Matlab, Excel, VBA, C/C++, R, C#, Java, Fortran and Python)

- University of Kaiserslautern, Germany, AG Wehn: Ant Colony Optimization Applet Visualization of Traveling Salesman solved by ant system with numerous options and parameters (Java Applet)

- Ant algorithm simulation (Java Applet)

- Java Ant Colony System Framework

- Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm Implementation (Python Notebook)