Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Crystal structure

View on Wikipedia

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material.[1] Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat along the principal directions of three-dimensional space in matter.

The smallest group of particles in a material that constitutes this repeating pattern is the unit cell of the structure. The unit cell completely reflects the symmetry and structure of the entire crystal, which is built up by repetitive translation of the unit cell along its principal axes. The translation vectors define the nodes of the Bravais lattice.

The lengths of principal axes/edges, of the unit cell and angles between them are lattice constants, also called lattice parameters or cell parameters. The symmetry properties of a crystal are described by the concept of space groups.[1] All possible symmetric arrangements of particles in three-dimensional space may be described by 230 space groups.

The crystal structure and symmetry play a critical role in determining many physical properties, such as cleavage, electronic band structure, and optical transparency.

Unit cell

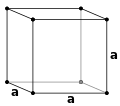

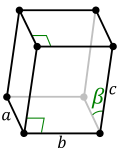

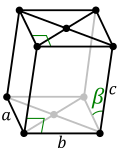

[edit]Crystal structure is described in terms of the geometry of the arrangement of particles in the unit cells. The unit cell is defined as the smallest repeating unit having the full symmetry of the crystal structure.[2] The geometry of the unit cell is defined as a parallelepiped, providing six lattice parameters taken as the lengths of the cell edges (a, b, c) and the angles between them (α, β, γ). The positions of particles inside the unit cell are described by the fractional coordinates (xi, yi, zi) along the cell edges, measured from a reference point. It is thus only necessary to report the coordinates of a smallest asymmetric subset of particles, called the crystallographic asymmetric unit. The asymmetric unit may be chosen so that it occupies the smallest physical space, which means that not all particles need to be physically located inside the boundaries given by the lattice parameters. All other particles of the unit cell are generated by the symmetry operations that characterize the symmetry of the unit cell. The collection of symmetry operations of the unit cell is expressed formally as the space group of the crystal structure.[3]

-

Simple cubic (P)

-

Body-centered cubic (I)

-

Face-centered cubic (F)

Miller indices

[edit]

Vectors and planes in a crystal lattice are described by the three-value Miller index notation. This syntax uses the indices h, k, and ℓ as directional parameters.[4]

By definition, the syntax (hkℓ) denotes a plane that intercepts the three points a1/h, a2/k, and a3/ℓ, or some multiple thereof. That is, the Miller indices are proportional to the inverses of the intercepts of the plane with the unit cell (in the basis of the lattice vectors). If one or more of the indices is zero, the planes do not intersect that axis (i.e., the intercept is "at infinity"). A plane containing a coordinate axis is translated to no longer contain that axis before its Miller indices are determined. The Miller indices for a plane are integers with no common factors. Negative indices are indicated with horizontal bars, as in (123). In an orthogonal coordinate system for a cubic cell, the Miller indices of a plane are the Cartesian components of a vector normal to the plane.

Considering only (hkℓ) planes intersecting one or more lattice points (the lattice planes), the distance d between adjacent lattice planes is related to the (shortest) reciprocal lattice vector orthogonal to the planes by the formula

Planes and directions

[edit]The crystallographic directions are geometric lines linking nodes (atoms, ions or molecules) of a crystal. Likewise, the crystallographic planes are geometric planes linking nodes. Some directions and planes have a higher density of nodes. These high-density planes influence the behaviour of the crystal as follows:[1]

- Optical properties: Refractive index is directly related to density (or periodic density fluctuations).

- Adsorption and reactivity: Physical adsorption and chemical reactions occur at or near surface atoms or molecules. These phenomena are thus sensitive to the density of nodes.

- Surface tension: The condensation of a material means that the atoms, ions or molecules are more stable if they are surrounded by other similar species. The surface tension of an interface thus varies according to the density on the surface.

- Microstructural defects: Pores and crystallites tend to have straight grain boundaries following higher density planes.

- Cleavage: This typically occurs preferentially parallel to higher density planes.

- Plastic deformation: Dislocation glide occurs preferentially parallel to higher density planes. The perturbation carried by the dislocation (Burgers vector) is along a dense direction. The shift of one node in a more dense direction requires a lesser distortion of the crystal lattice.

Some directions and planes are defined by symmetry of the crystal system. In monoclinic, trigonal, tetragonal, and hexagonal systems there is one unique axis (sometimes called the principal axis) which has higher rotational symmetry than the other two axes. The basal plane is the plane perpendicular to the principal axis in these crystal systems. For triclinic, orthorhombic, and cubic crystal systems the axis designation is arbitrary and there is no principal axis.

Cubic structures

[edit]For the special case of simple cubic crystals, the lattice vectors are orthogonal and of equal length (usually denoted a); similarly for the reciprocal lattice. So, in this common case, the Miller indices (ℓmn) and [ℓmn] both simply denote normals/directions in Cartesian coordinates. For cubic crystals with lattice constant a, the spacing d between adjacent (ℓmn) lattice planes is (from above):

Because of the symmetry of cubic crystals, it is possible to change the place and sign of the integers and have equivalent directions and planes:

- Coordinates in angle brackets such as ⟨100⟩ denote a family of directions that are equivalent due to symmetry operations, such as [100], [010], [001] or the negative of any of those directions.

- Coordinates in curly brackets or braces such as {100} denote a family of plane normals that are equivalent due to symmetry operations, much the way angle brackets denote a family of directions.

For face-centered cubic (fcc) and body-centered cubic (bcc) lattices, the primitive lattice vectors are not orthogonal. However, in these cases the Miller indices are conventionally defined relative to the lattice vectors of the cubic supercell and hence are again simply the Cartesian directions.

Interplanar spacing

[edit]The spacing d between adjacent (hkℓ) lattice planes is given by:[5][6]

- Cubic:

- Tetragonal:

- Hexagonal:

- Rhombohedral (primitive setting):

- Orthorhombic:

- Monoclinic:

- Triclinic:

Classification by symmetry

[edit]The defining property of a crystal is its inherent symmetry. Performing certain symmetry operations on the crystal lattice leaves it unchanged. All crystals have translational symmetry in three directions, but some have other symmetry elements as well. For example, rotating the crystal 180° about a certain axis may result in an atomic configuration that is identical to the original configuration; the crystal has twofold rotational symmetry about this axis. In addition to rotational symmetry, a crystal may have symmetry in the form of mirror planes, and also the so-called compound symmetries, which are a combination of translation and rotation or mirror symmetries. A full classification of a crystal is achieved when all inherent symmetries of the crystal are identified.[7]

Lattice systems

[edit]Lattice systems are a grouping of crystal structures according to the point groups of their lattice. All crystals fall into one of seven lattice systems. They are related to, but not the same as the seven crystal systems.

| Crystal family | Lattice system | Point group (Schönflies notation) |

14 Bravais lattices | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive (P) | Base-centered (S) | Body-centered (I) | Face-centered (F) | |||

| Triclinic (a) | Ci |

aP |

||||

| Monoclinic (m) | C2h |

mP |

mS |

|||

| Orthorhombic (o) | D2h |

oP |

oS |

oI |

oF | |

| Tetragonal (t) | D4h |

tP |

tI |

|||

| Hexagonal (h) | Rhombohedral | D3d |

hR |

|||

| Hexagonal | D6h |

hP |

||||

| Cubic (c) | Oh |

cP |

cI |

cF | ||

The most symmetric, the cubic or isometric system, has the symmetry of a cube, that is, it exhibits four threefold rotational axes oriented at 109.5° (the tetrahedral angle) with respect to each other. These threefold axes lie along the body diagonals of the cube. The other six lattice systems, are hexagonal, tetragonal, rhombohedral (often confused with the trigonal crystal system), orthorhombic, monoclinic and triclinic which is the least symmetrical as it possess only identity (E).

Bravais lattices

[edit]Bravais lattices, also referred to as space lattices, describe the geometric arrangement of the lattice points,[4] and therefore the translational symmetry of the crystal. The three dimensions of space afford 14 distinct Bravais lattices describing the translational symmetry. All crystalline materials recognized today, not including quasicrystals, fit in one of these arrangements. The fourteen three-dimensional lattices, classified by lattice system, are shown above.

The crystal structure consists of the same group of atoms, the basis, positioned around each and every lattice point. This group of atoms therefore repeats indefinitely in three dimensions according to the arrangement of one of the Bravais lattices. The characteristic rotation and mirror symmetries of the unit cell is described by its crystallographic point group.

Crystal systems

[edit]A crystal system is a set of point groups in which the point groups themselves and their corresponding space groups are assigned to a lattice system. Of the 32 point groups that exist in three dimensions, most are assigned to only one lattice system, in which case the crystal system and lattice system both have the same name. However, five point groups are assigned to two lattice systems, rhombohedral and hexagonal, because both lattice systems exhibit threefold rotational symmetry. These point groups are assigned to the trigonal crystal system.

| Crystal family | Crystal system | Point group / Crystal class | Schönflies | Point symmetry | Order | Abstract group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| triclinic | pedial | C1 | enantiomorphic polar | 1 | trivial | |

| pinacoidal | Ci (S2) | centrosymmetric | 2 | cyclic | ||

| monoclinic | sphenoidal | C2 | enantiomorphic polar | 2 | cyclic | |

| domatic | Cs (C1h) | polar | 2 | cyclic | ||

| prismatic | C2h | centrosymmetric | 4 | Klein four | ||

| orthorhombic | rhombic-disphenoidal | D2 (V) | enantiomorphic | 4 | Klein four | |

| rhombic-pyramidal | C2v | polar | 4 | Klein four | ||

| rhombic-dipyramidal | D2h (Vh) | centrosymmetric | 8 | |||

| tetragonal | tetragonal-pyramidal | C4 | enantiomorphic polar | 4 | cyclic | |

| tetragonal-disphenoidal | S4 | non-centrosymmetric | 4 | cyclic | ||

| tetragonal-dipyramidal | C4h | centrosymmetric | 8 | |||

| tetragonal-trapezohedral | D4 | enantiomorphic | 8 | dihedral | ||

| ditetragonal-pyramidal | C4v | polar | 8 | dihedral | ||

| tetragonal-scalenohedral | D2d (Vd) | non-centrosymmetric | 8 | dihedral | ||

| ditetragonal-dipyramidal | D4h | centrosymmetric | 16 | |||

| hexagonal | trigonal | trigonal-pyramidal | C3 | enantiomorphic polar | 3 | cyclic |

| rhombohedral | C3i (S6) | centrosymmetric | 6 | cyclic | ||

| trigonal-trapezohedral | D3 | enantiomorphic | 6 | dihedral | ||

| ditrigonal-pyramidal | C3v | polar | 6 | dihedral | ||

| ditrigonal-scalenohedral | D3d | centrosymmetric | 12 | dihedral | ||

| hexagonal | hexagonal-pyramidal | C6 | enantiomorphic polar | 6 | cyclic | |

| trigonal-dipyramidal | C3h | non-centrosymmetric | 6 | cyclic | ||

| hexagonal-dipyramidal | C6h | centrosymmetric | 12 | |||

| hexagonal-trapezohedral | D6 | enantiomorphic | 12 | dihedral | ||

| dihexagonal-pyramidal | C6v | polar | 12 | dihedral | ||

| ditrigonal-dipyramidal | D3h | non-centrosymmetric | 12 | dihedral | ||

| dihexagonal-dipyramidal | D6h | centrosymmetric | 24 | |||

| cubic | tetartoidal | T | enantiomorphic | 12 | alternating | |

| diploidal | Th | centrosymmetric | 24 | |||

| gyroidal | O | enantiomorphic | 24 | symmetric | ||

| hextetrahedral | Td | non-centrosymmetric | 24 | symmetric | ||

| hexoctahedral | Oh | centrosymmetric | 48 | |||

In total there are seven crystal systems: triclinic, monoclinic, orthorhombic, tetragonal, trigonal, hexagonal, and cubic.

Point groups

[edit]The crystallographic point group or crystal class is the mathematical group comprising the symmetry operations that leave at least one point unmoved and that leave the appearance of the crystal structure unchanged. These symmetry operations include

- Reflection, which reflects the structure across a reflection plane

- Rotation, which rotates the structure a specified portion of a circle about a rotation axis

- Inversion, which changes the sign of the coordinate of each point with respect to a center of symmetry or inversion point

- Improper rotation, which consists of a rotation about an axis followed by an inversion.

Rotation axes (proper and improper), reflection planes, and centers of symmetry are collectively called symmetry elements. There are 32 possible crystal classes. Each one can be classified into one of the seven crystal systems.

Space groups

[edit]In addition to the operations of the point group, the space group of the crystal structure contains translational symmetry operations. These include:

- Pure translations, which move a point along a vector

- Screw axes, which rotate a point around an axis while translating parallel to the axis.[8]

- Glide planes, which reflect a point through a plane while translating it parallel to the plane.[8]

There are 230 distinct space groups.

Atomic coordination

[edit]By considering the arrangement of atoms relative to each other, their coordination numbers, interatomic distances, types of bonding, etc., it is possible to form a general view of the structures and alternative ways of visualizing them.[9]

Close packing

[edit]

The principles involved can be understood by considering the most efficient way of packing together equal-sized spheres and stacking close-packed atomic planes in three dimensions. For example, if plane A lies beneath plane B, there are two possible ways of placing an additional atom on top of layer B. If an additional layer were placed directly over plane A, this would give rise to the following series:

- ...ABABABAB...

This arrangement of atoms in a crystal structure is known as hexagonal close packing (hcp).

If, however, all three planes are staggered relative to each other and it is not until the fourth layer is positioned directly over plane A that the sequence is repeated, then the following sequence arises:

- ...ABCABCABC...

This type of structural arrangement is known as cubic close packing (ccp).

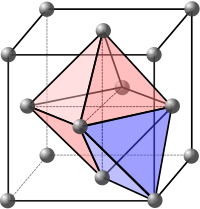

The unit cell of a ccp arrangement of atoms is the face-centered cubic (fcc) unit cell. This is not immediately obvious as the closely packed layers are parallel to the {111} planes of the fcc unit cell. There are four different orientations of the close-packed layers.

APF and CN

[edit]One important characteristic of a crystalline structure is its atomic packing factor (APF). This is calculated by assuming that all the atoms are identical spheres, with a radius large enough that each sphere abuts on the next. The atomic packing factor is the proportion of space filled by these spheres which can be worked out by calculating the total volume of the spheres and dividing by the volume of the cell as follows:

Another important characteristic of a crystalline structure is its coordination number (CN). This is the number of nearest neighbours of a central atom in the structure.

The APFs and CNs of the most common crystal structures are shown below:

| Crystal structure | Atomic packing factor | Coordination number (Geometry) |

|---|---|---|

| Diamond cubic | 0.34 | 4 (Tetrahedron) |

| Simple cubic | 0.52[10] | 6 (Octahedron) |

| Body-centered cubic (BCC) | 0.68[10] | 8 (Cube) |

| Face-centered cubic (FCC) | 0.74[10] | 12 (Cuboctahedron) |

| Hexagonal close-packed (HCP) | 0.74[10] | 12 (Triangular orthobicupola) |

The 74% packing efficiency of the FCC and HCP is the maximum density possible in unit cells constructed of spheres of only one size.

Interstitial sites

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2022) |

Interstitial sites refer to the empty spaces in between the atoms in the crystal lattice. These spaces can be filled by oppositely charged ions to form multi-element structures. They can also be filled by impurity atoms or self-interstitials to form interstitial defects.

Defects and impurities

[edit]Real crystals feature defects or irregularities in the ideal arrangements described above and it is these defects that critically determine many of the electrical and mechanical properties of real materials.

Impurities

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2022) |

When one atom substitutes for one of the principal atomic components within the crystal structure, alteration in the electrical and thermal properties of the material may ensue.[11] Impurities may also manifest as electron spin impurities in certain materials. Research on magnetic impurities demonstrates that substantial alteration of certain properties such as specific heat may be affected by small concentrations of an impurity, as for example impurities in semiconducting ferromagnetic alloys may lead to different properties as first predicted in the late 1960s.[12][13]

Dislocations

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2022) |

Dislocations in a crystal lattice are line defects that are associated with local stress fields. Dislocations allow shear at lower stress than that needed for a perfect crystal structure.[14] The local stress fields result in interactions between the dislocations which then result in strain hardening or cold working.

Grain boundaries

[edit]Grain boundaries are interfaces where crystals of different orientations meet.[4] A grain boundary is a single-phase interface, with crystals on each side of the boundary being identical except in orientation. The term "crystallite boundary" is sometimes, though rarely, used. Grain boundary areas contain those atoms that have been perturbed from their original lattice sites, dislocations, and impurities that have migrated to the lower energy grain boundary.

Treating a grain boundary geometrically as an interface of a single crystal cut into two parts, one of which is rotated, we see that there are five variables required to define a grain boundary. The first two numbers come from the unit vector that specifies a rotation axis. The third number designates the angle of rotation of the grain. The final two numbers specify the plane of the grain boundary (or a unit vector that is normal to this plane).[9]

Grain boundaries disrupt the motion of dislocations through a material, so reducing crystallite size is a common way to improve strength, as described by the Hall–Petch relationship. Since grain boundaries are defects in the crystal structure they tend to decrease the electrical and thermal conductivity of the material. The high interfacial energy and relatively weak bonding in most grain boundaries often makes them preferred sites for the onset of corrosion and for the precipitation of new phases from the solid. They are also important to many of the mechanisms of creep.[9]

Grain boundaries are in general only a few nanometers wide. In common materials, crystallites are large enough that grain boundaries account for a small fraction of the material. However, very small grain sizes are achievable. In nanocrystalline solids, grain boundaries become a significant volume fraction of the material, with profound effects on such properties as diffusion and plasticity. In the limit of small crystallites, as the volume fraction of grain boundaries approaches 100%, the material ceases to have any crystalline character, and thus becomes an amorphous solid.[9]

Prediction of structure

[edit]The difficulty of predicting stable crystal structures based on the knowledge of only the chemical composition has long been a stumbling block on the way to fully computational materials design. Now, with more powerful algorithms and high-performance computing, structures of medium complexity can be predicted using such approaches as evolutionary algorithms, random sampling, or metadynamics.

The crystal structures of simple ionic solids (e.g., NaCl or table salt) have long been rationalized in terms of Pauling's rules, first set out in 1929 by Linus Pauling, referred to by many since as the "father of the chemical bond".[15] Pauling also considered the nature of the interatomic forces in metals, and concluded that about half of the five d-orbitals in the transition metals are involved in bonding, with the remaining nonbonding d-orbitals being responsible for the magnetic properties. Pauling was therefore able to correlate the number of d-orbitals in bond formation with the bond length, as well as with many of the physical properties of the substance. He subsequently introduced the metallic orbital, an extra orbital necessary to permit uninhibited resonance of valence bonds among various electronic structures.[16]

In the resonating valence bond theory, the factors that determine the choice of one from among alternative crystal structures of a metal or intermetallic compound revolve around the energy of resonance of bonds among interatomic positions. It is clear that some modes of resonance would make larger contributions (be more mechanically stable than others), and that in particular a simple ratio of number of bonds to number of positions would be exceptional. The resulting principle is that a special stability is associated with the simplest ratios or "bond numbers": 1⁄2, 1⁄3, 2⁄3, 1⁄4, 3⁄4, etc. The choice of structure and the value of the axial ratio (which determines the relative bond lengths) are thus a result of the effort of an atom to use its valency in the formation of stable bonds with simple fractional bond numbers.[17][18]

After postulating a direct correlation between electron concentration and crystal structure in beta-phase alloys, Hume-Rothery analyzed the trends in melting points, compressibilities and bond lengths as a function of group number in the periodic table in order to establish a system of valencies of the transition elements in the metallic state. This treatment thus emphasized the increasing bond strength as a function of group number.[19] The operation of directional forces were emphasized in one article on the relation between bond hybrids and the metallic structures. The resulting correlation between electronic and crystalline structures is summarized by a single parameter, the weight of the d-electrons per hybridized metallic orbital. The "d-weight" calculates out to 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9 for the fcc, hcp and bcc structures respectively. The relationship between d-electrons and crystal structure thus becomes apparent.[20]

In crystal structure predictions/simulations, the periodicity is usually applied, since the system is imagined as being unlimited in all directions. Starting from a triclinic structure with no further symmetry property assumed, the system may be driven to show some additional symmetry properties by applying Newton's second law on particles in the unit cell and a recently developed dynamical equation for the system period vectors [21] (lattice parameters including angles), even if the system is subject to external stress.

Polymorphism

[edit]

Polymorphism is the occurrence of multiple crystalline forms of a material. It is found in many crystalline materials including polymers, minerals, and metals. According to Gibbs' rules of phase equilibria, these unique crystalline phases are dependent on intensive variables such as pressure and temperature. Polymorphism is related to allotropy, which refers to elemental solids. The complete morphology of a material is described by polymorphism and other variables such as crystal habit, amorphous fraction or crystallographic defects. Polymorphs have different stabilities and may spontaneously and irreversibly transform from a metastable form (or thermodynamically unstable form) to the stable form at a particular temperature.[22] They also exhibit different melting points, solubilities, and X-ray diffraction patterns.

One good example of this is the quartz form of silicon dioxide, or SiO2. In the vast majority of silicates, the Si atom shows tetrahedral coordination by 4 oxygens. All but one of the crystalline forms involve tetrahedral {SiO4} units linked together by shared vertices in different arrangements. In different minerals the tetrahedra show different degrees of networking and polymerization. For example, they occur singly, joined in pairs, in larger finite clusters including rings, in chains, double chains, sheets, and three-dimensional frameworks. The minerals are classified into groups based on these structures. In each of the 7 thermodynamically stable crystalline forms or polymorphs of crystalline quartz, only 2 out of 4 of each the edges of the {SiO4} tetrahedra are shared with others, yielding the net chemical formula for silica: SiO2.

Another example is elemental tin (Sn), which is malleable near ambient temperatures but is brittle when cooled. This change in mechanical properties due to existence of its two major allotropes, α- and β-tin. The two allotropes that are encountered at normal pressure and temperature, α-tin and β-tin, are more commonly known as gray tin and white tin respectively. Two more allotropes, γ and σ, exist at temperatures above 161 °C and pressures above several GPa.[23] White tin is metallic, and is the stable crystalline form at or above room temperature. Below 13.2 °C, tin exists in the gray form, which has a diamond cubic crystal structure, similar to diamond, silicon or germanium. Gray tin has no metallic properties at all, is a dull gray powdery material, and has few uses, other than a few specialized semiconductor applications.[24] Although the α–β transformation temperature of tin is nominally 13.2 °C, impurities (e.g. Al, Zn, etc.) lower the transition temperature well below 0 °C, and upon addition of Sb or Bi the transformation may not occur at all.[25]

Physical properties

[edit]Twenty of the 32 crystal classes are piezoelectric, and crystals belonging to one of these classes (point groups) display piezoelectricity. All piezoelectric classes lack inversion symmetry. Any material develops a dielectric polarization when an electric field is applied, but a substance that has such a natural charge separation even in the absence of a field is called a polar material. Whether or not a material is polar is determined solely by its crystal structure. Only ten of the 32 point groups are polar. All polar crystals are pyroelectric, so the ten polar crystal classes are sometimes referred to as the pyroelectric classes.

There are a few crystal structures, notably the perovskite structure, which exhibit ferroelectric behavior. This is analogous to ferromagnetism, in that, in the absence of an electric field during production, the ferroelectric crystal does not exhibit a polarization. Upon the application of an electric field of sufficient magnitude, the crystal becomes permanently polarized. This polarization can be reversed by a sufficiently large counter-charge, in the same way that a ferromagnet can be reversed. However, although they are called ferroelectrics, the effect is due to the crystal structure (not the presence of a ferrous metal).

See also

[edit]- Brillouin zone – a primitive cell in the reciprocal space lattice of a crystal

- Chemical crystallography before X-rays

- Crystal engineering

- Crystal growth – a major stage of a crystallization process

- Crystallographic database

- Fractional coordinates

- Frank–Kasper phases

- Hermann–Mauguin notation – a notation to represent symmetry in point groups, plane groups and space groups

- Laser-heated pedestal growth – a crystal growth technique

- Liquid crystal – a state of matter with properties of both conventional liquids and crystals

- Patterson function – a function used to solve the phase problem in X-ray crystallography

- Periodic table (crystal structure) – (for elements that are solid at standard temperature and pressure) gives the crystalline structure of the most thermodynamically stable form(s) in those conditions. In all other cases the structure given is for the element at its melting point.

- Primitive cell – a repeating unit formed by the vectors spanning the points of a lattice

- Seed crystal – a small piece of a single crystal used to initiate growth of a larger crystal

- Wigner–Seitz cell – a primitive cell of a crystal lattice with Voronoi decomposition applied

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hook, J.R.; Hall, H.E. (2010). Solid State Physics. Manchester Physics Series (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471928041.

- ^ West, Anthony R. (1999). Basic Solid State Chemistry (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-471-98756-7.

- ^ International Tables for Crystallography (2006). Volume A, Space-group symmetry.

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia of Physics (2nd Edition), R.G. Lerner, G.L. Trigg, VHC publishers, 1991, ISBN (Verlagsgesellschaft) 3-527-26954-1, ISBN (VHC Inc.) 0-89573-752-3

- ^ "4. Direct and reciprocal lattices". CSIC Dept de Cristalografia y Biologia Estructural. 6 Apr 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ Edington, J. W. (1975). Electron Diffraction in the Electron Microscope. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-02595-4. ISBN 978-0-333-18292-5.

- ^ Ashcroft, N.; Mermin, D. (1976). "Chapter 7". Solid State Physics. Brooks/Cole (Thomson Learning, Inc.). ISBN 978-0030493461.

- ^ a b Donald E. Sands (1994). "§4-2 Screw axes and §4-3 Glide planes". Introduction to Crystallography (Reprint of WA Benjamin corrected 1975 ed.). Courier-Dover. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0486678399.

- ^ a b c d Parker, C.B., ed. (1994). McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0070514003.

- ^ a b c d Ellis, Arthur B.; et al. (1995). Teaching General Chemistry: A Materials Science Companion (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. ISBN 084122725X.

- ^ Kallay, Nikola (2000). Interfacial Dynamics. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0824700065.

- ^ Hogan, C. M. (1969). "Density of States of an Insulating Ferromagnetic Alloy". Physical Review. 188 (2): 870–874. Bibcode:1969PhRv..188..870H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.188.870.

- ^ Zhang, X. Y.; Suhl, H (1985). "Spin-wave-related period doublings and chaos under transverse pumping". Physical Review A. 32 (4): 2530–2533. Bibcode:1985PhRvA..32.2530Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.32.2530. PMID 9896377.

- ^ Courtney, Thomas (2000). Mechanical Behavior of Materials. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-57766-425-3.

- ^ L. Pauling (1929). "The principles determining the structure of complex ionic crystals". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 51 (4): 1010–1026. Bibcode:1929JAChS..51.1010P. doi:10.1021/ja01379a006.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1938). "The Nature of the Interatomic Forces in Metals". Physical Review. 54 (11): 899–904. Bibcode:1938PhRv...54..899P. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.54.899.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1947). "Atomic Radii and Interatomic Distances in Metals". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 69 (3): 542–553. Bibcode:1947JAChS..69..542P. doi:10.1021/ja01195a024.

- ^ Pauling, L. (1949). "A Resonating-Valence-Bond Theory of Metals and Intermetallic Compounds". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 196 (1046): 343–362. Bibcode:1949RSPSA.196..343P. doi:10.1098/rspa.1949.0032.

- ^ Hume-rothery, W.; Irving, H. M.; Williams, R. J. P. (1951). "The Valencies of the Transition Elements in the Metallic State". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 208 (1095): 431. Bibcode:1951RSPSA.208..431H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1951.0172. S2CID 95981632.

- ^ Altmann, S. L.; Coulson, C. A.; Hume-Rothery, W. (1957). "On the Relation between Bond Hybrids and the Metallic Structures". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 240 (1221): 145. Bibcode:1957RSPSA.240..145A. doi:10.1098/rspa.1957.0073. S2CID 94113118.

- ^ Liu, Gang (2015). "Dynamical equations for the period vectors in a periodic system under constant external stress". Can. J. Phys. 93 (9): 974–978. arXiv:cond-mat/0209372. Bibcode:2015CaJPh..93..974L. doi:10.1139/cjp-2014-0518. S2CID 54966950.

- ^ Hanaor, Dorian A. H.; Sorrell, Charles C. (2011). "Review of the anatase to rutile phase transformation". Journal of Materials Science. 46 (4): 855–874. Bibcode:2011JMatS..46..855H. doi:10.1007/s10853-010-5113-0. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_60954.

- ^ Molodets, A. M.; Nabatov, S. S. (2000). "Thermodynamic Potentials, Diagram of State, and Phase Transitions of Tin on Shock Compression". High Temperature. 38 (5): 715–721. Bibcode:2000HTemp..38..715M. doi:10.1007/BF02755923. S2CID 120417927.

- ^ Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Tin". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 793–800. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- ^ Schwartz, Mel (2002). "Tin and Alloys, Properties". Encyclopedia of Materials, Parts and Finishes (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-56676-661-6.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Crystal structures at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Crystal structures at Wikimedia Commons

- The internal structure of crystals... Crystallography for beginners

- Different types of crystal structure

- Appendix A from the manual for Atoms, software for XAFS

- Intro to Minerals: Crystal Class and System

- Introduction to Crystallography and Mineral Crystal Systems

- Crystal planes and Miller indices

- Interactive 3D Crystal models

- Specific Crystal 3D models

- Crystallography Open Database (with more than 140,000 crystal structures)

Crystal structure

View on GrokipediaBasic Elements

Unit cell

In crystallography, the unit cell is defined as the smallest volume element of a crystal lattice that contains all the structural information necessary to describe the entire crystal, such that repeating this volume by pure translations fills the space without gaps or overlaps.[8] This parallelepiped-shaped building block serves as the fundamental repeating unit, encapsulating the positions of atoms, ions, or molecules relative to lattice points.[9] Unit cells are classified as primitive or non-primitive based on the number of lattice points they contain. A primitive unit cell, also known as a simple unit cell, includes exactly one lattice point and has the minimal volume required to represent the lattice translations.[10] In contrast, non-primitive unit cells, such as body-centered (with two lattice points) or face-centered (with four lattice points), contain additional lattice points at internal positions like the body center or face centers, resulting in larger volumes but often higher symmetry for practical description.[11] For example, the body-centered cubic structure features a lattice point at each corner and one at the cube's center, while the face-centered cubic adds points at the centers of each face.[10] The geometry of a unit cell is characterized by three lattice constants—, , and , representing the lengths of the edges along the three crystallographic axes—and three interaxial angles— (between edges and ), (between and ), and (between and ).[10] These parameters fully define the shape and size of the unit cell, varying across crystal systems; for instance, in the cubic system, and , forming a cube with equal edges and right angles.[8] In the hexagonal system, , with and , resulting in a hexagonal prism.[12] Visualizations of these often depict the cubic unit cell as a symmetric cube with atoms at corners (and possibly centers for non-primitive types), and the hexagonal unit cell as a taller prism with three equivalent basal edges forming 120° angles.[8][12] Through translational symmetry, identical unit cells are repeated infinitely in three dimensions along the lattice vectors, generating the complete crystal lattice as an extended periodic array.[9] This repetition ensures that every point in the crystal can be reached by integer combinations of the unit cell's defining vectors, preserving the structural integrity across the material.[10]Crystal lattice

A crystal lattice is defined as an infinite, periodic array of discrete points in three-dimensional space, where each point represents the position of a unit cell that repeats translationally to fill the entire volume without gaps or overlaps.[13] This arrangement captures the long-range order inherent to crystalline solids, distinguishing them from amorphous materials by their repeating translational symmetry. The periodicity of the crystal lattice is mathematically described by three primitive lattice vectors, conventionally denoted as , , and , which are non-coplanar and connect a lattice point to its nearest neighbors along the three independent directions.[14] Any lattice point can then be reached by integer linear combinations of these vectors: , where , , and are integers. These vectors define the fundamental translations that preserve the lattice structure, ensuring that the environment around every lattice point is identical.[15] The reciprocal lattice provides a dual representation in momentum space, constructed from basis vectors , , and that satisfy (with as the Kronecker delta), ensuring orthogonality to pairs of direct lattice vectors. Reciprocal lattice points correspond to wavevectors where plane waves exhibit the same periodicity as the direct lattice, making it indispensable for analyzing diffraction phenomena, as scattering intensities peak at these points in experiments like X-ray diffraction. In qualitative terms, direct space describes the real-space positions and arrangements of atoms within the crystal, while reciprocal space captures the Fourier transform of this density, relating spatial frequencies to scattering angles and enabling the interpretation of diffraction patterns as a map of the lattice's periodicity.[16] For instance, in a simple cubic lattice with lattice constant , the direct lattice vectors are , , , yielding lattice points at coordinates for integers . The corresponding reciprocal lattice is also simple cubic but scaled by , with points at for integers .[17]Indexing and Geometry

Miller indices

Miller indices are a symbolic notation system used in crystallography to designate the orientation of planes and directions within a crystal lattice relative to the unit cell axes. This system was introduced in 1839 by the British mineralogist and crystallographer William Hallowes Miller in his work A Treatise on Crystallography, providing a concise way to describe lattice features using small integers derived from geometric intercepts. The notation facilitates the analysis of crystal symmetry and structure without requiring detailed coordinate descriptions, making it essential for identifying specific atomic arrangements in materials.[12][18] For crystal planes, the Miller indices are denoted as (hkl), where h, k, and l are integers representing the reciprocals of the fractional intercepts that the plane makes with the crystallographic axes a, b, and c, respectively, scaled to the smallest integers by clearing fractions. To determine the indices, one identifies the intercepts of the plane on the axes (in units of the lattice parameters); takes the reciprocals; and multiplies through by the least common multiple of the denominators to obtain whole numbers, with the lowest values preferred. If a plane is parallel to an axis, the intercept is infinite, resulting in a zero index for that component (e.g., a plane parallel to the b- and c-axes has k = 0 and l = 0). Planes with negative intercepts are indicated by placing a bar over the index (e.g., (\bar{1}00)). The notation {hkl} refers to a family of equivalent planes related by the crystal's symmetry operations. For instance, in a cubic lattice, the (100) plane corresponds to a face of the unit cell parallel to the yz-plane, intersecting the a-axis at one unit length while being parallel to the others.[12][18] Directions in the crystal lattice are specified using Miller indices in the form [uvw], where u, v, and w are the smallest integers proportional to the components of the direction vector along the a, b, and c axes, respectively. Unlike planes, direction indices are not based on reciprocals but directly on the lattice vector coordinates, often reduced to the lowest terms. Negative directions are denoted with bars (e.g., [\bar{1}10]). The notationCrystal planes and directions

Crystal planes in a crystal structure are defined as families of parallel planes that pass through the lattice points, representing sets of atomic layers stacked in a repeating manner. These planes are fundamental to understanding the geometric arrangement of atoms within the lattice, as they delineate the layers where atoms are densely packed or exhibit specific bonding characteristics. In face-centered cubic (FCC) lattices, for instance, the {111} family of planes consists of close-packed atomic layers that form equilateral triangular arrangements, contributing to the high density and stability of these structures.[20][21] Crystal directions, in contrast, refer to straight lines that connect lattice points along specific vectors within the crystal lattice, defining pathways for atomic alignment or movement. These directions often coincide with the shortest lattice vectors or high-symmetry axes, influencing processes such as atomic diffusion or dislocation motion. In plastic deformation, slip directions are particular crystallographic directions along which dislocations glide, typically the close-packed directions like <110> in FCC crystals, enabling shear without bond breaking in other orientations.[22][23][24] Due to the symmetry of the crystal lattice, multiple planes and directions that are equivalent under rotational or reflection operations form families, denoted by curly braces {} for planes and angle brackets <> for directions. In cubic crystals, the <100> family includes all directions equivalent to [25], such as and , which point along the principal axes and exhibit identical physical properties due to the lattice's isotropic symmetry in these orientations.[20][22][26] Crystal planes and directions play a critical role in determining material properties, such as cleavage, where crystals fracture preferentially along planes of weak atomic bonding, like the {100} planes in some ionic crystals, resulting in smooth, flat surfaces. Similarly, during crystal growth, facets often develop perpendicular to low-index directions or along specific planes with minimal surface energy, influencing the overall morphology of the crystal. In hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structures, the basal plane, denoted as (0001), serves as a prominent example of a close-packed layer that governs anisotropic growth and deformation behaviors in materials like magnesium or zinc.[27][20][28]Interplanar spacing

Interplanar spacing, denoted as , represents the perpendicular distance between successive parallel crystal planes characterized by Miller indices . These planes are defined by their intercepts on the lattice axes, and the spacing provides a key geometric parameter for understanding crystal periodicity and diffraction behavior. The concept arises from the arrangement of atoms in the lattice, where parallel planes of atoms scatter waves constructively under specific conditions. In fractional coordinates (where positions are expressed relative to the lattice vectors), the equation for planes is (with integer for lattice planes). The general formula for interplanar spacing is , where is the reciprocal lattice vector, with reciprocal basis vectors defined such that (or 1 in some conventions). The magnitude is computed using the metric tensor of the reciprocal lattice, which accounts for the angles between direct lattice vectors. This reciprocal formulation is universal and simplifies calculations for diffraction, as is perpendicular to the planes by construction.[14] For crystal systems with orthogonal axes (cubic, tetragonal, orthorhombic), where all angles are 90° but edge lengths may differ, the formula simplifies to . In the cubic system, where , it further simplifies to . In the hexagonal system, accounting for the sixfold symmetry and ratio with , the expression is . These formulas enable precise computation of spacings from known lattice dimensions.[29][30] A primary application of interplanar spacing lies in X-ray diffraction, where Bragg's law relates it to observable diffraction angles: , with as the diffraction order, the X-ray wavelength, and the incidence angle. This equation allows experimental determination of from measured peak positions, facilitating crystal structure analysis without deriving the full interference conditions here.[31] Interplanar spacing is influenced by external factors that modify lattice parameters. Lattice strain, arising from mechanical deformation or defects, can compress or expand planes, shifting and thus diffraction peaks. Temperature effects occur via thermal expansion, where increasing heat causes lattice parameters to grow, enlarging proportionally; for instance, coefficients of thermal expansion quantify this change per degree Kelvin.[32][33] As an example, consider sodium chloride (NaCl), which adopts a face-centered cubic structure with lattice parameter Å. For the (111) planes, Å, illustrating how the formula yields atomic-scale distances relevant to ionic bonding and diffraction studies.[34]Symmetry Classification

Bravais lattices

A Bravais lattice is defined as an infinite array of discrete points in three-dimensional space where each point has an identical environment, generated solely by translational symmetry. These lattices represent the distinct ways to arrange points such that no two are equivalent except through pure translations, ensuring the lattice cannot be reduced to a simpler form by redefining the unit cell. In 1850, French physicist and crystallographer Auguste Bravais systematically enumerated these unique arrangements, identifying exactly 14 Bravais lattices in three dimensions.[35] The criteria for uniqueness among Bravais lattices emphasize that additional lattice points within the conventional unit cell must arise only from translations of the primitive vectors; any extraneous points would imply either a smaller primitive cell or a different lattice type, violating the minimal description. This leads to four primary centering types: primitive (P), where lattice points are only at the corners; base-centered (C), with additional points at the centers of two opposite faces; body-centered (I), with a point at the body center; and face-centered (F), with points at the centers of all six faces. These centering variations, combined with the geometric constraints of the lattice systems, yield the 14 distinct types.[35][36] The 14 Bravais lattices are classified within seven crystal systems, each defined by specific relationships among the unit cell parameters (lattice constants a, b, c and angles α, β, γ). For instance, the cubic system features equal lengths and right angles (a = b = c, α = β = γ = 90°), while the tetragonal system has a = b ≠ c and α = β = γ = 90°. Representative examples include the primitive cubic lattice in the cubic system and the body-centered tetragonal lattice in the tetragonal system. The full classification is summarized below:| Crystal System | Bravais Lattice Types | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | Primitive (P) | No symmetry constraints; a ≠ b ≠ c, α ≠ β ≠ γ. |

| Monoclinic | Primitive (P), Base-centered (C) | One right angle; a ≠ b ≠ c, α = γ = 90°, β ≠ 90°. |

| Orthorhombic | Primitive (P), Base-centered (C), Body-centered (I), Face-centered (F) | Three right angles; a ≠ b ≠ c, α = β = γ = 90°. |

| Tetragonal | Primitive (P), Body-centered (I) | Two equal lengths with right angles; a = b ≠ c, α = β = γ = 90°. |

| Trigonal (Rhombohedral) | Primitive (R) | a = b = c, α = β = γ ≠ 90°. |

| Hexagonal | Primitive (P) | a = b ≠ c, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°. |

| Cubic | Primitive (P), Body-centered (I), Face-centered (F) | a = b = c, α = β = γ = 90°. |

Lattice systems

Lattice systems classify the possible geometries of crystal lattices into seven distinct categories, determined by the constraints on the unit cell's edge lengths , , and the angles between them (between and ), (between and ), and (between and ). This classification arises from the requirement that the lattice must be periodic and translationally symmetric, with the systems reflecting increasing levels of metric symmetry from the lowest in triclinic to the highest in cubic. The grouping enables systematic analysis of crystal structures without considering full rotational symmetries, focusing solely on the metric relations that define distances and angles within the lattice./07%3A_Molecular_and_Solid_State_Structure/7.01%3A_Crystal_Structure) The seven lattice systems, along with their parameter constraints, are summarized in the following table:| Lattice System | Number of Bravais Lattices | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | arbitrary | 1 (primitive) | |||||

| Monoclinic | arbitrary | 2 (primitive, base-centered) | |||||

| Orthorhombic | arbitrary | 4 (primitive, base-centered, body-centered, face-centered) | |||||

| Tetragonal | arbitrary | 2 (primitive, body-centered) | |||||

| Trigonal (Rhombohedral) | 1 (rhombohedral) | ||||||

| Hexagonal | arbitrary | 1 (primitive) | |||||

| Cubic | 3 (primitive, body-centered, face-centered) |

Crystal systems

Crystal systems represent a fundamental classification in crystallography, grouping the 32 point groups into seven categories based on the overall symmetry compatible with the underlying lattice geometry. These systems—triclinic, monoclinic, orthorhombic, tetragonal, trigonal (or rhombohedral), hexagonal, and cubic—define the possible macroscopic symmetries of crystals by integrating rotational and reflection symmetries from point groups with the metric constraints of the lattice. Unlike lattice systems, which focus solely on geometric parameters like axis lengths and angles, crystal systems emphasize the full symmetry repertoire, ensuring that only point groups whose operations preserve the lattice are assigned to each category.[39][40] Each crystal system corresponds directly to one of the seven lattice systems, but restricts inclusion to point groups that align with the lattice's metric symmetry, creating a mapping that excludes incompatible symmetries. For instance, the orthorhombic lattice system (with three mutually perpendicular axes of unequal length) maps to the orthorhombic crystal system, which accommodates point groups like 222, mm2, and mmm, all of which respect the 90° angles and distinct axis lengths. Similarly, the cubic lattice system aligns with the cubic crystal system, incorporating high-symmetry point groups such as 23, m3, 432, \bar{4}3m, and m\bar{3}m, where operations like threefold and fourfold rotations are feasible due to equal axes and right angles. This mapping ensures that the symmetry elements do not distort the lattice, with lower-symmetry point groups fitting into higher-symmetry systems if their operations are subgroups.[41][40] Holohedry refers to the point group exhibiting the maximal symmetry within each crystal system, representing the "complete" form that includes all possible symmetry operations allowed by the lattice. For the cubic system, the holohedral group is m\bar{3}m (also denoted 4/m \bar{3} 2/m), featuring inversion, mirror planes, and multiple rotation axes, as seen in structures like halite (NaCl). In the triclinic system, the holohedry is simply \bar{1}, limited to inversion without rotations or mirrors, reflecting the absence of higher symmetries. These holohedral forms serve as benchmarks, with other point groups in the system being hemihedral or merohedral subgroups that omit certain operations.[42][40] Illustrative examples highlight the diversity: the isometric (cubic) crystal system demonstrates maximal isotropy, with equal lattice parameters (a = b = c) and α = β = γ = 90°, enabling highly symmetric minerals like diamond (point group 4/m \bar{3} 2/m) or pyrite (point group \bar{4} 3 m). Conversely, the anorthic (triclinic) system lacks any symmetry constraints beyond the lattice, with arbitrary parameters (a ≠ b ≠ c, α ≠ β ≠ γ ≠ 90°), as in turquoise (point group 1) or microcline (point group \bar{1}), where even basic rotations are absent. These extremes underscore how crystal systems encapsulate both geometric and symmetric aspects./07%3A_Molecular_and_Solid_State_Structure/7.01%3A_Crystal_Structure)[41] Transitions between crystal systems arise from subtle variations in lattice parameters or symmetry-breaking during phase changes, reclassifying structures when parameters deviate from defining thresholds. For example, a cubic system (a = b = c, all angles 90°) may shift to tetragonal if one axis elongates slightly (a = b ≠ c, angles 90°), reducing the point group from m\bar{3}m to 4/mmm, as observed in some perovskites under pressure. Similarly, orthorhombic symmetry can distort to monoclinic by tilting one angle away from 90°, lowering the holohedry from mmm to 2/m; such changes often occur in temperature-driven phase transitions, where thermal expansion or atomic displacements break higher symmetries while preserving lower ones. These transitions illustrate the continuum of symmetry in crystals, governed by energetic stability.[43][44]Point groups

Point groups in crystallography refer to the finite collections of symmetry operations—rotations, reflections, and inversions—that map a crystal lattice onto itself when performed around a fixed point, preserving the overall periodicity of the structure. These groups describe the external symmetry of crystals without involving translations, focusing solely on operations that leave a central point invariant. The possible rotation axes are limited to 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 6-fold due to compatibility with translational symmetry in three dimensions./02%3A_Rotational_Symmetry/2.04%3A_Crystallographic_Point_Groups) The fundamental symmetry elements comprising these point groups include the identity operation (which leaves the lattice unchanged), proper rotations about principal axes (denoted as n-fold, where n = 1, 2, 3, 4, or 6), mirror planes (perpendicular or parallel to axes), the inversion center (which maps each point to its opposite through the origin), and improper rotoinversions (combinations of rotation and inversion). For instance, a 2-fold rotation reverses direction by 180 degrees, while a mirror plane reflects across its surface. These elements combine in specific ways to form closed groups under composition, ensuring all operations are consistent with lattice invariance.[40][45] There are exactly 32 crystallographic point groups, arising from the permissible combinations of these elements that align with the seven crystal systems. They are denoted using two primary notations: the Schoenflies system (common in molecular spectroscopy, e.g., D_{4h} for a group with a 4-fold axis, horizontal mirrors, and dihedral planes) and the international (Hermann-Mauguin) system (standard in crystallography, e.g., 4/mmm for the same group, indicating a 4-fold axis with mirrors and dihedral planes). Examples include the trivial group 1 (or C_1, no symmetry beyond identity) in the triclinic system and the highly symmetric O_h (or m\bar{3}m) in the cubic system, which incorporates 48 operations including 3-fold, 4-fold, and 2-fold axes along multiple directions.[42][46] These 32 point groups are distributed across the crystal systems as follows: 2 in triclinic (1, \bar{1}), 3 in monoclinic (2, m, 2/m), 3 in orthorhombic (222, mm2, mmm), 7 in tetragonal (4, \bar{4}, 4/m, 422, 4mm, \bar{4}2m, 4/mmm), 5 in trigonal (3, \bar{3}, 32, 3m, \bar{3}m), 7 in hexagonal (6, \bar{6}, 6/m, 622, 6mm, \bar{6}m2, 6/mmm), and 5 in cubic (23, m\bar{3}, 432, \bar{4}3m, m\bar{3}m). This distribution reflects the increasing symmetry constraints from lower (triclinic) to higher (cubic) systems, with cubic hosting the highest symmetry groups. For clarity, the groups can be summarized in the following table, using international notation with representative Schoenflies equivalents:| Crystal System | Number of Point Groups | Examples (International / Schoenflies) |

|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | 2 | 1 / C_1, \bar{1} / C_i |

| Monoclinic | 3 | 2 / C_2, m / C_s, 2/m / C_{2h} |

| Orthorhombic | 3 | 222 / D_2, mm2 / C_{2v}, mmm / D_{2h} |

| Tetragonal | 7 | 4 / C_4, 4mm / C_{4v}, 4/mmm / D_{4h} |

| Trigonal | 5 | 3 / C_3, 3m / C_{3v}, \bar{3}m / D_{3d} |

| Hexagonal | 7 | 6 / C_6, 6mm / C_{6v}, 6/mmm / D_{6h} |

| Cubic | 5 | 23 / T, 432 / O, m\bar{3}m / O_h |

Space groups

Space groups represent the complete set of symmetries for periodic crystal structures in three dimensions, extending the 32 crystallographic point groups by incorporating lattice translations along with nonsymmorphic operations such as screw axes and glide planes. These elements allow the symmetry operations to fill space while maintaining the periodic arrangement of atoms. There are exactly 230 distinct space groups, enumerated and classified in the International Tables for Crystallography.[50] Of these, 73 are symmorphic space groups, which combine point group operations with pure lattice translations without fractional shifts, whereas the remaining 157 are nonsymmorphic, featuring screw axes (rotations combined with partial translations parallel to the axis) or glide planes (reflections combined with partial translations parallel to the plane)./03:_Space_Groups/3.04:_Group_Properties) Space groups are denoted using the Hermann–Mauguin symbol, as standardized in the International Tables for Crystallography, which specifies the lattice type, principal axes, and any nonsymmorphic elements.[50] For instance, the symbol P2₁/c describes a primitive (P) monoclinic lattice with a twofold screw axis (2₁) and a glide plane (c) perpendicular to the b-axis, reflecting combined rotational and translational symmetries. The distribution of the 230 space groups varies by crystal system, reflecting the increasing constraints on symmetry as metric parameters become more equal:| Crystal System | Number of Space Groups |

|---|---|

| Triclinic | 2 |

| Monoclinic | 13 |

| Orthorhombic | 59 |

| Tetragonal | 68 |

| Trigonal | 25 |

| Hexagonal | 27 |

| Cubic | 36 |

Atomic Coordination

Close packing

Close packing represents the most efficient geometric arrangement of identical spheres, maximizing space utilization in crystal structures by minimizing voids between them. This arrangement begins with a two-dimensional hexagonal layer, where each sphere contacts six neighbors, forming a close-packed plane. Subsequent layers are stacked by placing spheres in the tetrahedral depressions—triangular voids formed by three spheres in the underlying layer—resulting in three possible positions labeled A, B, and C, depending on their lateral offset relative to the first layer. The specific stacking sequence of these layers defines distinct three-dimensional structures. Hexagonal close packing (HCP) follows an ABAB... pattern, with the third layer aligning directly above the first (A position), repeating every two layers to yield a hexagonal symmetry. Cubic close packing (CCP), equivalent to the face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice, employs an ABCABC... sequence, where each successive layer occupies a new position, producing cubic symmetry after three layers. Both HCP and CCP achieve identical maximum density for equal spheres.[53] Many elemental metals adopt these close-packed structures due to their simple metallic bonding. For instance, copper (Cu) crystallizes in the FCC arrangement, while magnesium (Mg) forms an HCP structure.[54] In these packings, the nestled spheres create inherent voids: octahedral sites, coordinated by six surrounding spheres, and tetrahedral sites, bounded by four. Each close-packed unit contains one octahedral void and two tetrahedral voids per sphere, providing potential spaces within the otherwise dense array.[55] Both HCP and FCC exhibit the highest atomic packing factor among elemental crystal structures, serving as a benchmark for density.[56]Atomic packing factor and coordination number

The atomic packing factor (APF), also known as packing efficiency, quantifies the fraction of the unit cell volume occupied by the atoms in a crystal structure, assuming hard-sphere atoms that touch along the closest-packed directions. It is calculated as the total volume of atoms within the unit cell divided by the volume of the unit cell itself.[57] The coordination number (CN) represents the number of nearest-neighbor atoms surrounding a given atom in the lattice, providing insight into the local atomic environment and stability.[58] These metrics are fundamental for understanding density and bonding in crystalline materials, with higher APF and CN generally indicating denser packing and stronger metallic or ionic interactions.[59] For the simple cubic (SC) structure, the APF is derived as follows: the unit cell contains 1 atom (contributed by 8 corners × 1/8), with lattice parameter where is the atomic radius, since atoms touch along the edge. The volume of the atom is , and the unit cell volume is . Thus, [60] The CN in SC is 6, corresponding to the six nearest neighbors along the three orthogonal axes.[58] In the body-centered cubic (BCC) structure, 2 atoms occupy the unit cell (8 corners × 1/8 + 1 center), and atoms touch along the body diagonal, giving since the diagonal length is . The total atomic volume is , and the unit cell volume is . Substituting yields [56] The CN for BCC is 8, with the eight nearest neighbors equivalently located along the body-diagonal directions.[58] The face-centered cubic (FCC) structure, along with hexagonal close-packed (HCP), achieves the maximum APF for spherical atoms. It has 4 atoms per unit cell (8 corners × 1/8 + 6 faces × 1/2), with atoms touching along the face diagonal, so as the diagonal is . The total atomic volume is , and the unit cell volume is . Thus, [60] The CN in FCC and HCP is 12, reflecting the close-packed arrangement where each atom has twelve nearest neighbors in the plane and adjacent layers.[58] This highest APF value is realized in close-packed structures like FCC and HCP.[59] A correlation exists between CN and APF: structures with higher CN, such as FCC (CN=12, APF=0.74) versus BCC (CN=8, APF=0.68) or SC (CN=6, APF=0.52), exhibit greater packing efficiency due to more optimal spatial filling by nearest neighbors.[61] In ionic crystals, such as sodium chloride (NaCl) adopting the rock salt structure, both Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions have a CN of 6, forming an FCC-like arrangement of anions with cations in octahedral sites, resulting in a balanced packing suited to their radius ratio.[62]Interstitial sites

In crystal lattices, interstitial sites are voids or gaps between the primary atoms that can accommodate smaller atoms or ions without significantly distorting the structure. These sites are particularly prominent in close-packed structures such as face-centered cubic (FCC) and hexagonal close-packed (HCP), where they arise from the efficient arrangement of spheres./08%3A_Ionic_and_Covalent_Solids_-_Structures/8.02%3A_Close-packing_and_Interstitial_Sites) The two primary types of interstitial sites in close-packed lattices are tetrahedral and octahedral. A tetrahedral site is surrounded by four host atoms arranged at the corners of a tetrahedron, providing 4-fold coordination to any inserted atom. In contrast, an octahedral site is bounded by six host atoms in an octahedral geometry, offering 6-fold coordination./08%3A_Ionic_and_Covalent_Solids_-_Structures/8.02%3A_Close-packing_and_Interstitial_Sites)[63] The size of these sites is characterized by the radius ratio, defined as the maximum radius of an interstitial atom () relative to the host atom radius () that can fit without overlap. For tetrahedral sites in FCC and HCP structures, this ratio is 0.225, while for octahedral sites, it is 0.414. These ratios determine stable insertion: smaller interstitial atoms, such as hydrogen, preferentially occupy tetrahedral sites due to the tighter fit (e.g., radius ratio ≈0.2 for H in many metals), whereas larger ones like carbon favor octahedral sites.[64][65] In close-packed structures, the number of interstitial sites per host atom is fixed: there are two tetrahedral sites and one octahedral site per atom. For an FCC unit cell with four atoms, this corresponds to eight tetrahedral sites and four octahedral sites. Similarly, HCP structures exhibit the same ratio per atom./08%3A_Ionic_and_Covalent_Solids_-_Structures/8.02%3A_Close-packing_and_Interstitial_Sites) Geometrically, in the FCC unit cell, octahedral sites are located at the body center () and at the centers of each edge (e.g., ), while tetrahedral sites occupy positions along the body diagonals, such as and equivalent sites. These coordinates reflect the symmetry of the lattice and ensure the sites are equidistant from surrounding atoms.[63][66] Practical examples illustrate the role of these sites. In austenitic steel, carbon atoms occupy octahedral interstitial sites in the FCC iron lattice, enabling solid solution strengthening up to about 2 wt% carbon. For hydrogen storage, metals like aluminum and certain transition metal alloys accommodate hydrogen in tetrahedral sites, as seen in interstitial hydrides where the small hydrogen radius (≈0.37 Å) fits the 0.225 ratio relative to typical host atoms (e.g., Al at 1.43 Å).[67]Crystal Defects

Point defects and impurities

Point defects are localized disruptions in the crystal lattice confined to one or a few atomic sites, contrasting with extended defects like lines or planes. These include intrinsic defects such as vacancies and interstitials, as well as extrinsic defects from impurities. They arise due to thermal fluctuations, irradiation, or intentional addition during synthesis, influencing mechanical, electrical, and optical properties of materials. Vacancies represent the simplest intrinsic point defect, where an atom or ion is absent from its regular lattice position, creating a void. In elemental crystals like metals, a single vacancy suffices, but in ionic compounds, charge balance requires paired cation and anion vacancies to avoid net charge, known as a Schottky defect. Schottky defects predominate in crystals with similar ion sizes, such as NaCl, where both Na⁺ and Cl⁻ vacancies form to maintain electroneutrality. The formation of these defects involves breaking bonds and rearranging neighboring atoms, typically requiring energies on the order of 1-2 eV per vacancy pair.[68] Frenkel defects, another intrinsic type prevalent in ionic crystals with significant size disparity between cations and anions, involve a cation displacing to an interstitial site, leaving a vacancy behind. This maintains overall charge neutrality without requiring surface incorporation. Common in compounds like AgBr or ZnS, Frenkel defects enhance ionic conductivity by facilitating ion hopping. Unlike Schottky defects, they do not alter the total number of lattice sites but redistribute ions.[69] Interstitial defects occur when an extra atom occupies a position between regular lattice sites, often in open structures like close-packed metals. These can be self-interstitials from host atoms or foreign interstitial impurities, such as carbon in iron, which occupies octahedral or tetrahedral voids. Interstitials distort the lattice more severely than vacancies due to bond compression, leading to higher formation energies, typically 3-5 eV. In ionic crystals, interstitials must pair with vacancies to preserve neutrality, as in Frenkel defects.[70][71] Substitutional impurities replace host atoms at lattice sites, forming solid solutions up to certain limits determined by atomic size mismatch (Hume-Rothery rules) and solubility. For instance, phosphorus atoms substituting silicon in semiconductors create n-type material by donating an extra valence electron to the conduction band, enabling controlled electrical conductivity. Dopants like phosphorus are introduced at concentrations around 10^{15}-10^{18} cm^{-3}, far exceeding thermal defect levels, to tailor device performance. Solid solution limits, often below 1-10 at.% for many systems, prevent phase separation and maintain single-crystal integrity.[72] The equilibrium concentration of point defects follows the Boltzmann distribution, approximately , where is the defect formation energy, is Boltzmann's constant, and is temperature; this yields extremely low intrinsic concentrations (e.g., ~10^{-17} at room temperature for typical eV), that rise exponentially with heat treatment. Point defects profoundly affect properties: vacancies and interstitials mediate diffusion, while impurities enable doping for semiconductors. Color centers, such as the F-center in NaCl—an electron trapped in a Cl⁻ vacancy—absorb visible light, imparting yellow coloration to the otherwise transparent crystal upon irradiation. In oxides like TiO₂ or ZrO₂, oxygen vacancies act as electron donors, enhancing n-type conductivity and catalytic activity by creating localized states in the bandgap.[73][74][75]Line defects: dislocations

Line defects, known as dislocations, are one-dimensional imperfections in the crystal lattice that extend along lines and play a crucial role in enabling plastic deformation at stresses far below the theoretical shear strength of perfect crystals.[76] These defects were first proposed independently by G.I. Taylor, E. Orowan, and M. Polanyi in 1934 to explain the observed low yield stresses in metals, where slip occurs along specific crystal planes and directions known as slip systems.[77] Dislocations distort the lattice locally, creating long-range elastic strain fields that interact with each other and with applied stresses, facilitating shear without breaking atomic bonds across the entire plane. Dislocations are classified into three main types based on the orientation of their line direction relative to the Burgers vector, a vector that quantifies the magnitude and direction of the lattice distortion: edge, screw, and mixed. An edge dislocation arises from the insertion or omission of an extra half-plane of atoms, resulting in a Burgers vector perpendicular to the dislocation line; this creates compressive strain above the line and tensile strain below it in the slip plane.[76] A screw dislocation, in contrast, involves a shear displacement where the Burgers vector is parallel to the dislocation line, producing a helical distortion that allows the dislocation to propagate perpendicular to the shear direction. Mixed dislocations combine characteristics of both, with the Burgers vector at an intermediate angle to the line direction, and are the most common form observed in deformed crystals.[77] The Burgers vector b is formally defined through the Burgers circuit: a closed loop drawn around the dislocation line in the actual distorted lattice fails to close in a perfect reference lattice, and the closure failure vector is b, given by b = ∮ dl, where the integral is taken along the circuit. In crystalline materials, b is typically a lattice translation vector, such as a/2⟨110⟩ in face-centered cubic metals, ensuring the distortion is consistent with the periodicity of the lattice and minimizing the energy of the defect.[76] This vector not only characterizes the type of dislocation but also determines the slip system along which it moves, linking the defect directly to the crystal's symmetry. Dislocation density, denoted ρ and measured in lines per unit area (typically in cm⁻²), varies widely depending on processing and deformation history, ranging from about 10⁶ cm⁻² in well-annealed metals to 10¹² cm⁻² in heavily deformed ones.[78] Annealing treatments reduce ρ by promoting annihilation of dislocations with opposite Burgers vectors and rearrangement into lower-energy configurations, such as subgrain boundaries, thereby softening the material.[79] Dislocations move primarily through two mechanisms: glide and climb, both driven by resolved shear stresses but differing in atomic processes. Glide is a conservative motion where the dislocation translates in its slip plane without changing the number of atoms, occurring via shear of atomic planes and controlled by the Peierls stress—the intrinsic lattice resistance arising from the periodic potential that dislocations must overcome. This stress, first calculated by R. Peierls in 1940 using a sinusoidal potential model, is exponentially sensitive to the dislocation core width and typically low in metals (on the order of G/1000, where G is the shear modulus), enabling room-temperature plasticity. Climb, a non-conservative process requiring diffusion of vacancies or interstitials, allows motion perpendicular to the slip plane and is thermally activated, becoming significant at high temperatures. In metals, dislocations are responsible for work hardening, where plastic deformation increases strength through multiplication (e.g., via Frank-Read sources) and interactions that create tangles and forests, impeding further glide and raising the flow stress proportionally to √ρ. For instance, in face-centered cubic copper, initial densities around 10⁷ cm⁻² rise to 10¹¹ cm⁻² after cold working, leading to significant hardening before recovery processes dominate during annealing.[78]Planar defects: grain boundaries

Grain boundaries are two-dimensional interfaces that separate adjacent crystalline regions, or grains, within a polycrystalline material, arising from variations in crystallographic orientation during solidification or deformation. These planar defects play a crucial role in determining the mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties of materials by influencing dislocation motion and atomic transport. In metals and ceramics, grain boundaries typically span thicknesses of a few atomic layers and can exhibit periodic or disordered atomic arrangements depending on the degree of misorientation between the grains.[80] Grain boundaries are classified into low-angle and high-angle types based on the misorientation angle θ between the adjacent lattices. Low-angle grain boundaries, with θ < 15°, consist of ordered arrays of dislocations that accommodate the small rotational mismatch, as described by the dislocation model developed by Read and Shockley. High-angle grain boundaries, with θ > 15°, feature more disordered structures resembling an amorphous interphase, lacking long-range periodicity and often exhibiting higher defect densities. Tilt grain boundaries, which involve rotation about an axis perpendicular to the boundary plane, are modeled as arrays of edge dislocations, while twist grain boundaries, involving rotation about an axis normal to the boundary plane, are composed of screw dislocation networks. These models highlight how dislocations serve as building blocks for low-angle boundaries, linking them conceptually to line defects within grains.[81][82] The energy of grain boundaries, a key thermodynamic property, typically ranges from 0.1 to 1 J/m² in metals, reflecting the disruption to atomic bonding at the interface. For low-angle boundaries, the Read-Shockley equation quantifies this energy as where γ is the boundary energy, γ₀ is a constant related to dislocation core energy, θ is the misorientation angle in radians, and A is a material-dependent parameter. This logarithmic dependence predicts lower energies for small θ, aligning with experimental observations in materials like aluminum and copper. High-angle boundaries generally have higher, more constant energies due to their disordered nature.[83][81] Grain boundaries significantly affect material behavior by serving as fast diffusion paths for atoms and vacancies, accelerating processes like creep and sintering compared to bulk diffusion. They also act as preferential sites for precipitation of second phases, which can enhance or degrade properties depending on the precipitate type. In terms of mechanical strengthening, grain boundaries impede dislocation glide, leading to the Hall-Petch relationship, where yield strength σ_y increases with decreasing grain size d as σ_y = σ_0 + k d^{-1/2}, with σ_0 and k as material constants; this effect is prominent in polycrystalline metals like steel and titanium.[84][85] Prominent examples of grain boundaries occur in polycrystalline metals, such as aluminum alloys used in aerospace applications, where they form networks that control fatigue resistance. Triple junctions, the points where three grain boundaries meet, introduce additional complexity, often exhibiting dihedral angles governed by energy balance and serving as nucleation sites for recrystallization or intergranular fracture in materials like nickel-based superalloys.[86][87]Structure Determination and Prediction

Experimental methods for structure determination