Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pressure ulcer

View on Wikipedia

| Pressure ulcer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Decubitus (plural: decubitūs), or decubitous ulcers, pressure injuries, pressure sores, bedsores |

| |

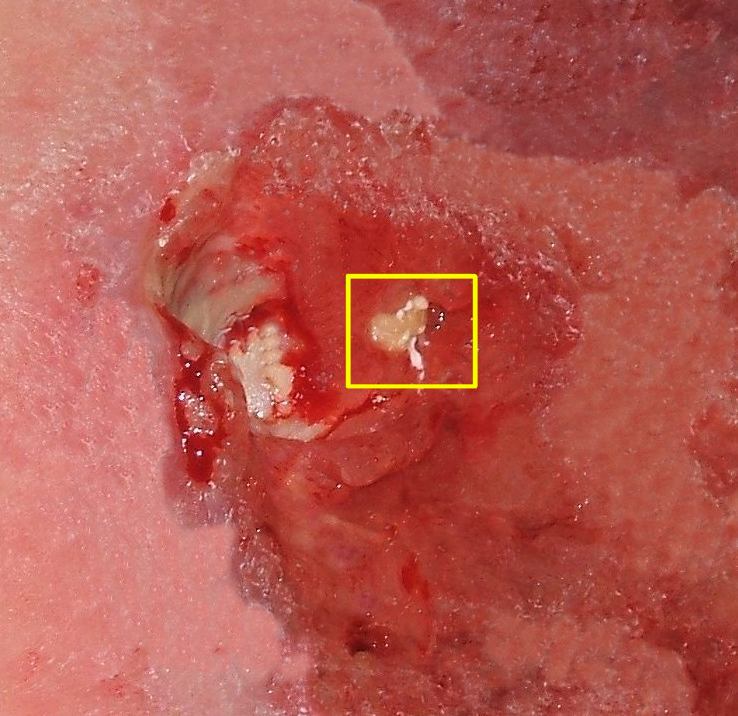

| Stage IV decubitus displaying the tuberosity of the ischium protruding through the tissue, and possible onset of osteomyelitis. | |

| Specialty | Plastic surgery |

| Complications | infection |

Pressure ulcers, also known as pressure sores, bed sores or pressure injuries, are localised damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue that usually occur over a bony prominence as a result of usually long-term pressure, or pressure in combination with shear or friction. The most common sites are the skin overlying the sacrum, coccyx, heels, and hips, though other sites can be affected, such as the elbows, knees, ankles, back of shoulders, or the back of the cranium.

Pressure ulcers occur due to pressure applied to soft tissue resulting in completely or partially obstructed blood flow to the soft tissue. Shear is also a cause, as it can pull on blood vessels that feed the skin. Pressure ulcers most commonly develop in individuals who are not moving about, such as those who are on chronic bedrest or consistently use a wheelchair. It is widely believed that other factors can influence the tolerance of skin for pressure and shear, thereby increasing the risk of pressure ulcer development. These factors are protein-calorie malnutrition, microclimate (skin wetness caused by sweating or incontinence), diseases that reduce blood flow to the skin, such as arteriosclerosis, or diseases that reduce the sensation in the skin, such as paralysis or neuropathy. The healing of pressure ulcers may be slowed by the age of the person, medical conditions (such as arteriosclerosis, diabetes or infection), smoking or medications such as anti-inflammatory drugs.

Although often prevented and treatable if detected early, pressure ulcers can be very difficult to prevent in critically ill people, frail elders, and individuals with impaired mobility such as wheelchair users (especially where spinal injury is involved). Primary prevention is to redistribute pressure by regularly turning the person. The benefit of turning to avoid further sores is well documented since at least the 19th century.[1] In addition to turning and re-positioning the person in the bed or wheelchair, eating a balanced diet with adequate protein[2] and keeping the skin free from exposure to urine and stool is important.[3]

The rate of pressure ulcers in hospital settings is high; the prevalence in European hospitals ranges from 8.3% to 23%, and the prevalence was 26% in Canadian healthcare settings from 1990 to 2003.[4] In 2013, there were 29,000 documented deaths from pressure ulcers globally, up from 14,000 deaths in 1990.[5]

The United States has tracked rates of pressure injury since the early 2000s. Whittington and Briones reported nationwide rates of pressure injuries in hospitals of 6% to 8%.[6] By the early 2010s, one study showed the rate of pressure injury had dropped to about 4.5% across the Medicare population following the introduction of the International Guideline for pressure injury prevention.[7] Padula and colleagues have witnessed a +29% uptick in pressure injury rates in recent years associated with the rollout of penalizing Medicare policies.[8]

Presentation

[edit]Complications

[edit]Pressure ulcers can trigger other ailments, cause considerable suffering, and can be expensive to treat. Some complications include autonomic dysreflexia, bladder distension, bone infection, pyarthrosis, sepsis, amyloidosis, anemia, urethral fistula, gangrene and very rarely malignant transformation (Marjolin's ulcer – secondary carcinomas in chronic wounds). Sores may recur if those with pressure ulcers do not follow recommended treatment or may instead develop seromas, hematomas, infections, or wound dehiscence. Paralyzed individuals are the most likely to have pressure sores recur. In some cases, complications from pressure sores can be life-threatening. The most common causes of fatality stem from kidney failure and amyloidosis. Pressure ulcers are also painful, with individuals of all ages and all stages of pressure ulcers reporting pain.[citation needed]

Cause

[edit]There are four mechanisms that contribute to pressure ulcer development:[9]

- External (interface) pressure applied over an area of the body, especially over the bony prominences can result in obstruction of the blood capillaries, which deprives tissues of oxygen and nutrients, causing ischemia (deficiency of blood in a particular area), hypoxia (inadequate amount of oxygen available to the cells), edema, inflammation, and, finally, necrosis and ulcer formation. Ulcers due to external pressure occur over the sacrum and coccyx, followed by the trochanter and the calcaneus (heel). In healthy individuals, ulcers caused by external pressure do not occur when the body is stationary, such as during sleep, as involuntary movements of the body frequently occur, allowing for repositioning and the relief of pressure.[10]

- Friction is damaging to the superficial blood vessels directly under the skin. It occurs when two surfaces rub against each other. The skin over the elbows can be injured due to friction. The back can also be injured when patients are pulled or slid over bed sheets while being moved up in bed or transferred onto a stretcher.

- Shearing is a separation of the skin from underlying tissues. When a patient is partially sitting up in bed, skin may stick to the sheet, making the skin susceptible to shearing in case underlying tissues move downward with the body toward the foot of the bed. This may also be possible on a patient who slides down while sitting in a chair.

- Moisture is also a common pressure ulcer culprit. Sweat, urine, feces, or excessive wound drainage can further exacerbate the damage done by pressure, friction, and shear. It can contribute to maceration of surrounding skin thus potentially expanding the deleterious effects of pressure ulcers.

Risk factors

[edit]There are over 100 risk factors for pressure ulcers.[11] Factors that may place a patient at risk include immobility, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, malnutrition, cerebral vascular accident and hypotension.[11][12] Other factors are age of 70 years and older, current smoking history, dry skin, low body mass index, urinary and fecal incontinence, physical restraints, malignancy, vasopressin prescription, and history of prior pressure injury development.[13]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Pressure ulcers may be caused by inadequate blood supply and resulting reperfusion injury when blood re-enters tissue. A simple example of a mild pressure sore may be experienced by healthy individuals while sitting in the same position for extended periods of time: the dull ache experienced is indicative of impeded blood flow to affected areas. Within 2 hours, this shortage of blood supply, called ischemia, may lead to tissue damage and cell death. The sore will initially start as a red, painful area. The other process of pressure ulcer development is seen when pressure is high enough to damage the cell membrane of muscle cells. The muscle cells die as a result and skin fed through blood vessels coming through the muscle die. This is the deep tissue injury form of pressure ulcers and begins as purple intact skin.[14]

According to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, pressure ulcers are one of the eight preventable iatrogenic illnesses. If a pressure ulcer is acquired in the hospital, the hospital will no longer receive reimbursement for the person's care. Hospitals spend about $27 billion annually for treatment of pressure injuries.[15] Whereas, the cost of pressure injury prevention is cost-effective, if not cost-saving, and would cost less than half the amount of resources to prevent compared to treat in health systems.[16]

Sites

[edit]

Common pressure sore sites include the skin over the coccyx, the sacrum, the ischia/ischium, the heels of the feet, over the heads of the long bones of the foot, buttocks, over the shoulder, and over the back of the head.[17]

Pressure reduction

[edit]Pressure must be removed from high risk body areas by frequent changes in position in bed or chair including turning side to side. Chair cushions and air mattresses should be used for immobile patients. Heels should be off of the bed.

Adequate diet

[edit]Eating by mouth is preferred and intake of food and fluid should meet calorie, protein and fluid needs. Work with a dietician if needed. Supplements may be needed.

Biofilm

[edit]Biofilm is one of the most common reasons for delayed healing in pressure ulcers. Biofilm occurs rapidly in wounds and stalls healing by keeping the wound inflamed. Frequent debridement and antimicrobial dressings are needed to control the biofilm. Infection prevents the healing of pressure ulcers. Signs of pressure ulcer infection include slow or delayed healing and pale granulation tissue. Signs and symptoms of systemic infection include fever, pain, redness, swelling, warmth of the area, and purulent discharge. Additionally, infected wounds may have a gangrenous smell, be discolored, and may eventually produce more pus.[citation needed]

In order to eliminate this problem, it is imperative to apply antiseptics at once. Hydrogen peroxide (a near-universal toxin) is not recommended for this task as it increases inflammation and impedes healing.[18] Cleaning the open wound with hypochlorous acid is helpful. Dressings with cadexomer iodine, silver, or honey have been shown to penetrate bacterial biofilms. Systemic antibiotics are not recommended in treating local infection in a pressure ulcer, as it can lead to bacterial resistance. They are only recommended if there is evidence of advancing cellulitis, bony infection, or bacteria in the blood.[19]

Diagnosis

[edit]Classification

[edit]

The definitions of the pressure ulcer stages are revised periodically by the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP)[20] in the United States and the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) in Europe.[21] Different classification systems are used around the world, depending upon the health system, the health discipline and the purpose for the classifying (e.g. health care versus, prevalence studies versus funding.[22] Briefly, they are as follows:[23][24]

- Stage 1: Intact skin with non-blanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching; its color may differ from the surrounding area. The area differs in characteristics such as thickness and temperature as compared to adjacent tissue. Stage 1 may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. May indicate "at risk" persons (a heralding sign of risk).

- Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled blister. Presents as a shiny or dry shallow ulcer without slough or bruising. This stage should not be used to describe skin tears, tape burns, perineal dermatitis, maceration or excoriation.

- Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. Slough may be present but does not obscure the depth of tissue loss. May include undermining and tunneling. The depth of a stage 3 pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue and stage 3 ulcers can be shallow. In contrast, areas of significant adiposity can develop extremely deep stage 3 pressure ulcers. Bone/tendon is not visible or directly palpable.

- Stage 4: Full thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some parts of the wound bed. Often include undermining and tunneling. The depth of a stage 4 pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue and these ulcers can be shallow. Stage 4 ulcers can extend into muscle and/or supporting structures (e.g., fascia, tendon or joint capsule) making osteomyelitis likely to occur. Exposed bone/tendon is visible or directly palpable. In 2012, the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel stated that pressure ulcers with exposed cartilage are also classified as a stage 4.

- Unstageable: Full thickness tissue loss in which actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough (yellow, tan, gray, green or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown or black) in the wound bed. Until enough slough and/or eschar is removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth, and therefore stage, cannot be determined. Stable (dry, adherent, intact without erythema or fluctuance) eschar on the heels is normally protective and should not be removed.

- Deep Tissue Pressure Injury (formerly suspected deep tissue injury): Intact or non-intact skin with localized area of persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon, purple discoloration or epidermal separation revealing a dark wound bed or blood filled blister. Pain and temperature change[25][26][27][28][29][30][31] often precede skin color changes. Discoloration may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. This injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure and shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury, or may resolve without tissue loss. If necrotic tissue, subcutaneous tissue, granulation tissue, fascia, muscle or other underlying structures are visible, this indicates a full thickness pressure injury (Unstageable, Stage 3 or Stage 4). Do not use DTPI to describe vascular, traumatic, neuropathic, or dermatologic conditions.[32]

The term medical device related pressure ulcer refers to a cause rather than a classification. Pressure ulcers from a medical device are classified according to the same classification system being used for pressure ulcers arising from other causes, but the cause is usually noted. Pressure injury from medical devices on mucous membranes should not be staged.

Ischemic fasciitis

[edit]Ischemic fasciitis (IF) is a benign tumor in the class of fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors[33] that, like pressure ulcers, may develop in elderly, bed-ridden individuals.[34] These tumors commonly form in the subcutaneous tissues (i.e. lower most tissue layer of the skin) that overlie bony protuberances such as those in or around the hip, shoulder, greater trochanter of the femur, iliac crest, lumbar region, or scapular region.[35] IF tumors differ from pressure ulcers in that they typically do not have extensive ulcerations of the skin and on histopathological microscopic analysis lack evidence of acute inflammation as determined by the presence of various types of white blood cells.[36] These tumors are commonly treated by surgical removal.[37]

Prevention

[edit]There are various approaches that are used widely for preventing pressure ulcers.[38] Suggested approaches include modifications to bedding and mattresses, different support systems for taking pressure off of affected areas, airing of surfaces of the body, skin care, nutrition, and organizational modifications (for example, changing the care routines in hospitals or homes where people require extended bedrest).[38][39] Overall, unbiased clinical studies to determine the effectiveness of these types of interventions and to determine the most effective intervention are needed in order to best prevent pressure ulcers.[38][40][41][42][43]

Clinical guidelines for preventing pressure ulcers

[edit]Numerous evidence-based and expert consensus-based clinical guidelines have been to developed to help guide medical professionals internationally[22] and in specific countries including the UK.[44][45][46] The Standardized Pressure Injury Prevention Protocol (SPIPP) Checklist is a derivative of the International Guideline that was designed to facilitate consistent implementation of pressure injury prevention.[47] In 2022, United States Congress passed legislation updating the Military Construction and Veterans Affairs and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2015 (H.R. 4355) to establish the SPIPP Checklist as law that United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities should adhere to in order to keep patients safe from harm.

Risk assessment

[edit]Before turning and repositioning a person, a risk assessment tool is suggested to determine what is the best approach for preventing pressure ulcers in that person. Some of the most common risk assessment tools are the Braden Scale, Norton, or Waterlow tools. The type of risk assessment tool that is used, will depend on which hospital the patient is admitted to and the location. After the risk assessment tool is used, a plan will be developed for the patient individually to prevent Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries. This plan will consist of different turning and repositioning strategies. These risk assessment tools provide the nursing staff with a baseline for each patient regarding their individual risk for acquiring a pressure injury. Factors that contribute to these risk assessment tools are moisture, activity, and mobility. These factors are considered and scored using the scale being used, whether it be the Braden, Norton, or Waterlow scale. The numbers are then added up and based on that final number, a score will be given and appropriate measures will be taken to ensure that the patient is being properly repositioned. Unfortunately, this is not always completed in hospitals like it should be.[48]

Efforts in the United States and South Korea have sought to automate risk assessment and classification by training machine learning models on electronic health records.[49][50][51]

Redistribution of pressure

[edit]An important aspect of care for most people at risk for pressure ulcers and those with bedsores is the redistribution of pressure so that no pressure is applied to the pressure ulcer.[52] In the 1940s Ludwig Guttmann introduced a program of turning paraplegics every two hours thus allowing bedsores to heal. Previously such individuals had a two-year life-expectancy, normally succumbing to blood and skin infections. Guttmann had learned the technique from the work of Boston physician Donald Munro.[53] There is lack of evidence on prevention of pressure ulcer whether the patient is put in 30 degrees position or at the standard 90 degrees position.[54]

Nursing homes and hospitals usually set programs in place to avoid the development of pressure ulcers in those who are bedridden, such as using a routine time frame for turning and repositioning to reduce pressure. The frequency of turning and repositioning depends on the person's level of risk.[citation needed]

Various interventions have been developed to redistribute pressure including the use of different bed mattresses, support surfaces, and the use of static chairs.

Support surfaces

[edit]The use of different types of mattresses including high density foam, surfaces with reactive fibers or gels in them, and surfaces that incorporate reactive water are sometimes suggested to redistribute pressure. The evidence supporting these interventions and whether they prevent new ulcers, increase the comfort level, or have other positive or more negative adverse effects is weak.[55][56] Many support surfaces redistribute pressure by immersing and/or enveloping the body into the surface. Some support surfaces, including antidecubitus mattresses and cushions, contain multiple air chambers that are alternately pumped.[57][58] Methods to standardize the products and evaluate the efficacy of these products have only been developed in recent years through the work of the S3I within NPUAP.[59]

There is some evidence that the use of foam mattresses is not as effective as support approaches that include alternating pressure air surfaces or reactive surfaces.[60][61] It is not clear if interventions that include a reactive air surface are more effective than reactive surfaces that include water or gel or other substrates.[62][63] In addition, the effectiveness of sheepskin overlays on top of mattresses is not clear.[38]

Evidence is uncertain regarding which support surfaces are most effective for pressure ulcer healing. While reactive air surfaces may promote healing more effectively than foam in some cases, the evidence is limited and inconsistent.[38]

Static chairs (as opposed to wheelchairs) have also been suggested for pressure redistribution.[64] Static chairs can include: standard hospital chairs; chairs with no cushions or manual/dynamic function; and chairs with integrated pressure redistributing surfaces and recline, rise or tilt functions. More research is needed to establish how effective pressure redistributing static chairs are for preventing pressure ulcers.[64]

For individuals with limited mobility, pressure shifting on a regular basis and using a wheelchair cushion featuring pressure relief components can help prevent pressure wounds.[65]

Nutrition

[edit]The benefits of nutritional interventions with various compositions for pressure ulcer prevention are uncertain.[66] The International Guideline on Pressure Injury Prevention and Treatment lists evidence-based recommendations for prevention of pressure injury and their treatment.[citation needed]

Organisational changes

[edit]There is some suggestion that organisational changes may reduce incidence of pressure ulcers, with healthcare professionals central to the prevention of pressure ulcers in both hospital[67] and community settings.[68] It is not clear from studies on the effectiveness of these approaches as to the best organisational change that would benefit those at risk of pressure ulcers including organisation of health services,[39] risk assessment tools,[69] wound care teams,[70] and education.[71][72] This is largely due to the lack of high-quality research in these areas.

Wound care and dressings

[edit]Caring for wounds and ulcers that have been started and the use of creams are also considerations in preventing worsening to ulcers and new primary ulcers. It is unclear if creams containing fatty acids are effective in reducing incidence of pressure ulcers compared to creams without fatty acids.[73] It is also unclear if silicone dressings reduce pressure ulcer incidence.[73] There is no evidence that massage reduces pressure ulcer incidence.[74] Controlling the heat and moisture levels of the skin surface, known as skin microclimate management, may also play a role in the prevention and control of pressure ulcers.[75] Skin care is also important because damaged skin does not tolerate pressure. However, skin that is damaged by exposure to urine or stool is not considered a pressure ulcer. These skin wounds should be classified as Incontinence Associated Dermatitis.[citation needed]

Treatment

[edit]Recommendations to treat pressure ulcers include the use of bed rest, pressure redistributing support surfaces, nutritional support, repositioning, wound care (e.g. debridement, wound dressings) and biophysical agents (e.g. electrical stimulation).[46] Reliable scientific evidence to support the use of many of these interventions, though, is lacking. More research is needed to assess how to best support the treatment of pressure ulcers, for example by repositioning.[40][76][42][43]

Debridement

[edit]Necrotic tissue should be removed in most pressure ulcers. The heel is an exception in many cases when the limb has an inadequate blood supply. Necrotic tissue is an ideal area for bacterial growth, which has the ability to greatly compromise wound healing. There are five ways to remove necrotic tissue.

- Autolytic debridement is the use of moist dressings to promote autolysis with the body's own enzymes and white blood cells. It is a slow process, but mostly painless, and is most effective in individuals with a properly functioning immune system.

- Biological debridement, or maggot debridement therapy, is the use of medical maggots to feed on necrotic tissue and therefore clean the wound of excess bacteria. Although this fell out of favor for many years, in January 2004, the FDA approved maggots as a live medical device.[77]

- Chemical debridement, or enzymatic debridement, is the use of prescribed enzymes that promote the removal of necrotic tissue.

- Mechanical debridement, is the use of debriding dressings, whirlpool or ultrasound for slough in a stable wound.

- Surgical debridement, or sharp debridement, is the fastest method, as it allows a surgeon to quickly remove dead tissue.

Dressings

[edit]It is not clear if one topical agent or dressing is better than another for treating pressure ulcers.[78] There is some evidence to suggest that protease-modulating dressings, foam dressings or collagenase ointment may be better at healing than gauze.[78] The wound dressing should be selected based on the wound and condition of the surrounding skin. There are some studies that indicate that antimicrobial products that stimulate the epithelization may improve the wound healing.[79] However, there is no international consensus on the selection of the dressings for pressure ulcers.[80] Evidence supporting the use of alginate dressings,[81] foam dressings,[82] and hydrogel dressings,[83] and the benefits of these dressings over other treatments is unclear.

Some guidelines for dressing are:[84]

| Condition | Cover dressing |

|---|---|

| None to moderate exudates | Gauze with tape or composite |

| Moderate to heavy exudates | Foam dressing with tape or composite |

| Frequent soiling | Hydrocolloid dressing, film or composite |

| Fragile skin | Stretch gauze or stretch net |

Other treatments

[edit]Other treatments include anabolic steroids,[85] medical grade honey,[86] negative pressure wound therapy,[87] phototherapy,[88] pressure relieving devices,[89] reconstructive surgery,[90] support surfaces,[91] ultrasound[92] and topical phenytoin.[93] There is little or no evidence to support or refute the benefits of most of these treatments compared to each other and placebo. It is not clear if electrical stimulation is an effective treatment for pressure ulcers.[94] In addition, the benefit of using systemic or topical antibiotics in the management of pressure ulcer is still unclear.[95] When selecting treatments, consideration should be given to patients' quality of life as well as the interventions' ease of use, reliability, and cost. The benefits of nutritional interventions with various compositions for pressure ulcer treatment are uncertain.[96]

Epidemiology

[edit]Each year, more than 2.5 million people in the United States develop pressure ulcers.[97] In acute care settings in the United States, the incidence of bedsores is 0.4% to 38%; within long-term care it is 2.2% to 23.9%, and in home care, it is 0% to 17%. Similarly, there is wide variation in prevalence: 10% to 18% in acute care, 2.3% to 28% in long-term care, and 0% to 29% in home care. There is a much higher rate of bedsores in intensive care units because of immunocompromised individuals, with 8% to 40% of those in the ICU developing bedsores.[98] However, pressure ulcer prevalence is highly dependent on the methodology used to collect the data. Using the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) methodology there are similar figures for pressure ulcers in acutely sick people in the hospital. There are differences across countries, but using this methodology, pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe was consistently high, from 8.3% (Italy) to 22.9% (Sweden).[99] A recent study in Jordan also showed a figure in this range.[100] Some research shows differences in pressure-ulcer detection among white and black residents in nursing homes.[101]

See also

[edit]- Perfusion – systemic biomechanics of blood delivery

References

[edit]- ^ Black JM, Edsberg LE, Baharestani MM, Langemo D, Goldberg M, McNichol L, et al. (February 2011). "Pressure ulcers: avoidable or unavoidable? Results of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Consensus Conference". Ostomy/Wound Management. 57 (2): 24–37. PMID 21350270.

- ^ Saghaleini SH, Dehghan K, Shadvar K, Sanaie S, Mahmoodpoor A, Ostadi Z (April 2018). "Pressure Ulcer and Nutrition". Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 22 (4): 283–289. doi:10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_277_17. PMC 5930532. PMID 29743767.

- ^ Boyko TV, Longaker MT, Yang GP (February 2018). "Review of the Current Management of Pressure Ulcers". Advances in Wound Care. 7 (2): 57–67. doi:10.1089/wound.2016.0697. PMC 5792240. PMID 29392094.

- ^ McInnes E, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SE, Dumville JC, Middleton V, Cullum N (September 2015). "Support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9) CD001735. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001735.pub5. PMC 7075275. PMID 26333288.

- ^ Mensah GA, Roth GA, Sampson UK, Moran AE, Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, et al. (GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators) (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ Whittington KT, Briones R (Nov 2004). "National Prevalence and Incidence Study: 6-year sequential acute care data". Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 17 (9): 490–494. doi:10.1097/00129334-200411000-00016. PMID 15632743. S2CID 22039909.

- ^ Lyder CH, Wang Y, Metersky M, Curry M, Kliman R, Verzier NR, et al. (September 2012). "Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: results from the national Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System study". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 60 (9): 1603–1608. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04106.x. PMID 22985136. S2CID 26120917.

- ^ Padula WV, Black JM, Davidson PM, Kang SY, Pronovost PJ (June 2020). "Adverse Effects of the Medicare PSI-90 Hospital Penalty System on Revenue-Neutral Hospital-Acquired Conditions". Journal of Patient Safety. 16 (2): e97 – e102. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000517. hdl:10453/142988. PMID 30110019. S2CID 52001575.

- ^ Grey JE, Harding KG, Enoch S (February 2006). "Pressure ulcers". BMJ. 332 (7539): 472–475. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7539.472. PMC 1382548. PMID 16497764.

- ^ "Causes and prevention of pressure sores". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Retrieved 2025-10-03.

- ^ a b Lyder CH (January 2003). "Pressure ulcer prevention and management". JAMA. 289 (2): 223–226. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.223. PMID 12517234. S2CID 29969042.

- ^ Berlowitz DR, Wilking SV (November 1989). "Risk factors for pressure sores. A comparison of cross-sectional and cohort-derived data". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 37 (11): 1043–1050. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb06918.x. PMID 2809051. S2CID 26013510.

- ^ Padula WV, Gibbons RD, Pronovost PJ, Hedeker D, Mishra MK, Makic MB, et al. (April 2017). "Using clinical data to predict high-cost performance coding issues associated with pressure ulcers: a multilevel cohort model". Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 24 (e1): e95 – e102. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocw118. PMC 7651933. PMID 27539199.

- ^ Edsberg LE, Black JM, Goldberg M, McNichol L, Moore L, Sieggreen M (Nov 2016). "Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System". Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 43 (6): 585–597. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000281. PMC 5098472. PMID 27749790.

- ^ Padula WV, Delarmente BA (June 2019). "The national cost of hospital-acquired pressure injuries in the United States". International Wound Journal. 16 (3): 634–640. doi:10.1111/iwj.13071. PMC 7948545. PMID 30693644. S2CID 59338649.

- ^ Padula WV, Mishra MK, Makic MB, Sullivan PW (April 2011). "Improving the quality of pressure ulcer care with prevention: a cost-effectiveness analysis". Medical Care. 49 (4): 385–392. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820292b3. PMID 21368685. S2CID 205815239.

- ^ Bhat S (2013). Srb's Manual of Surgery (4 ed.). Jaypee Brother Medical Pub. p. 21. ISBN 978-93-5025-944-3.

- ^ "Dealing with Pressure Sores | Pressure Care". Airospring. 31 January 2017.

- ^ Bluestein D, Javaheri A (November 2008). "Pressure ulcers: prevention, evaluation, and management". American Family Physician. 78 (10): 1186–1194. PMID 19035067. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ "National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP)".

- ^ "European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel". EPUAP.

- ^ a b Haesler E, et al. (National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (U.S.), European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance) (2019). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline (3rd ed.). internationalguideline.com. ISBN 978-0-6480097-8-8.

- ^ Edsberg LE, Black JM, Goldberg M, McNichol L, Moore L, Sieggreen M (2016). "Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System". Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 43 (6): 585–597. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000281. PMC 5098472. PMID 27749790.

- ^ Haesler E (2014). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Quick reference guide (Second ed.). Perth, Western Australia: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (U.S.), European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. ISBN 978-0-9579343-6-8. OCLC 945954574.

- ^ Black J (September 2018). "Using thermography to assess pressure injuries in patients with dark skin". Nursing. 48 (9): 60–61. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000544232.97340.96. PMID 30134324. S2CID 52070950.

- ^ Holster M (April 2023). "Driving Outcomes and Improving Documentation with Long-Wave Infrared Thermography in a Long-term Acute Care Hospital". Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 36 (4): 189–193. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000912676.73372.a8. PMID 36790265. S2CID 256869477.

- ^ "Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline". www.internationalguideline.com. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Farid KJ, Winkelman C, Rizkala A, Jones K (August 2012). "Using temperature of pressure-related intact discolored areas of skin to detect deep tissue injury: an observational, retrospective, correlational study". Ostomy/Wound Management. 58 (8): 20–31. PMID 22879313.

- ^ Koerner S, Adams D, Harper SL, Black JM, Langemo DK (July 2019). "Use of Thermal Imaging to Identify Deep-Tissue Pressure Injury on Admission Reduces Clinical and Financial Burdens of Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries". Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 32 (7): 312–320. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000559613.83195.f9. PMC 6716560. PMID 31192867.

- ^ Bhargava A, Chanmugam A, Herman C (February 2014). "Heat transfer model for deep tissue injury: a step towards an early thermographic diagnostic capability". Diagnostic Pathology. 9 36. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-9-36. PMC 3996098. PMID 24555856.

- ^ Simman R, Angel C (February 2022). "Early Identification of Deep-Tissue Pressure Injury Using Long-Wave Infrared Thermography: A Blinded Prospective Cohort Study". Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 35 (2): 95–101. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000790448.22423.b0. PMID 34469910. S2CID 237388229.

- ^ Edsberg LE, Black JM, Goldberg M, McNichol L, Moore L, Sieggreen M (2016). "Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System". Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 43 (6): 585–597. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000281. PMC 5098472. PMID 27749790.

- ^ Sbaraglia M, Bellan E, Dei Tos AP (April 2021). "The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: news and perspectives". Pathologica. 113 (2): 70–84. doi:10.32074/1591-951X-213. PMC 8167394. PMID 33179614.

- ^ Fukunaga M (September 2001). "Atypical decubital fibroplasia with unusual histology". APMIS. 109 (9): 631–635. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0463.2001.d01-185.x. PMID 11878717. S2CID 29499215.

- ^ Montgomery EA, Meis JM, Mitchell MS, Enzinger FM (July 1992). "Atypical decubital fibroplasia. A distinctive fibroblastic pseudotumor occurring in debilitated patients". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 16 (7): 708–715. doi:10.1097/00000478-199207000-00009. PMID 1530110. S2CID 21116139.

- ^ Liegl B, Fletcher CD (October 2008). "Ischemic fasciitis: analysis of 44 cases indicating an inconsistent association with immobility or debilitation". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 32 (10): 1546–1552. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816be8db. PMID 18724246. S2CID 24664236.

- ^ Sakamoto A, Arai R, Okamoto T, Yamada Y, Yamakado H, Matsuda S (October 2018). "Ischemic Fasciitis of the Left Buttock in a 40-Year-Old Woman with Beta-Propeller Protein-Associated Neurodegeneration (BPAN)". The American Journal of Case Reports. 19: 1249–1252. doi:10.12659/AJCR.911300. PMC 6206622. PMID 30341275.

- ^ a b c d e Shi C, Dumville JC, Cullum N, Rhodes S, McInnes E, Goh EL, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (August 2021). "Beds, overlays and mattresses for preventing and treating pressure ulcers: an overview of Cochrane Reviews and network meta-analysis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (8) CD013761. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013761.pub2. PMC 8407250. PMID 34398473.

- ^ a b Joyce P, Moore ZE, Christie J (December 2018). "Organisation of health services for preventing and treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (12) CD012132. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012132.pub2. PMC 6516850. PMID 30536917.

- ^ a b Moore ZE, van Etten MT, Dumville JC (October 2016). "Bed rest for pressure ulcer healing in wheelchair users". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (10) CD011999. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011999.pub2. PMC 6457936. PMID 27748506.

- ^ Langer G, Wan CS, Fink A, Schwingshackl L, Schoberer D (February 2024). "Nutritional interventions for preventing and treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2024 (2) CD003216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003216.pub3. PMC 10860148. PMID 38345088.

- ^ a b Moore ZE, Cowman S (January 2015). "Repositioning for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD006898. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006898.pub4. PMC 7389249. PMID 25561248.

- ^ a b Moore ZE, Cowman S (March 2013). "Wound cleansing for pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (3) CD004983. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004983.pub3. PMC 7389880. PMID 23543538.

- ^ Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment and Prevention: Recommendations (PDF). London: Royal College of Nursing. 2001. ISBN 1-873853-74-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 8 October 2021.[page needed]

- ^ "Pressure Relief and Wound Care". Archived from the original on 2013-09-30. Independent Living (UK)

- ^ a b National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (2014). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide (PDF). Perth, Australia: Cambridge Media. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-9579343-6-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ Padula WV, Black JM (February 2019). "The Standardized Pressure Injury Prevention Protocol for improving nursing compliance with best practice guidelines". Journal of Clinical Nursing. 28 (3–4): 367–371. doi:10.1111/jocn.14691. PMID 30328652. S2CID 53524143.

- ^ Li Z, Marshall AP, Lin F, Ding Y, Chaboyer W (August 2022). "Pressure injury prevention practices among medical surgical nurses in a tertiary hospital: An observational and chart audit study". International Wound Journal. 19 (5): 1165–1179. doi:10.1111/iwj.13712. PMC 9284631. PMID 34729917.

- ^ Kaewprag P, Newton C, Vermillion B, Hyun S, Huang K, Machiraju R (July 2017). "Predictive models for pressure ulcers from intensive care unit electronic health records using Bayesian networks". BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 17 (Suppl 2) 65. doi:10.1186/s12911-017-0471-z. PMC 5506589. PMID 28699545.

- ^ Cramer EM, Seneviratne MG, Sharifi H, Ozturk A, Hernandez-Boussard T (September 2019). "Predicting the Incidence of Pressure Ulcers in the Intensive Care Unit Using Machine Learning". eGEMs. 7 (1): 49. doi:10.5334/egems.307. PMC 6729106. PMID 31534981.

- ^ Cho I, Park I, Kim E, Lee E, Bates DW (November 2013). "Using EHR data to predict hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a prospective study of a Bayesian Network model". International Journal of Medical Informatics. 82 (11): 1059–1067. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.06.012. PMID 23891086.

- ^ Reilly EF, Karakousis GC, Schrag SP, Stawicki SP (2007). "Pressure ulcers in the intensive care unit: The 'forgotten' enemy". OPUS 12 Scientist. 1 (2): 17–30.

- ^ Whitteridge D (2004). "Guttmann, Sir Ludwig (1899–1980)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Gillespie BM, Walker RM, Latimer SL, Thalib L, Whitty JA, McInnes E, et al. (June 2020). "Repositioning for pressure injury prevention in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6) CD009958. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009958.pub3. PMC 7265629. PMID 32484259.

- ^ Shi C, Dumville JC, Cullum N, Rhodes S, Jammali-Blasi A, McInnes E, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (May 2021). "Alternating pressure (active) air surfaces for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5) CD013620. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013620.pub2. PMC 8108044. PMID 33969911.

- ^ Shi C, Dumville JC, Cullum N, Rhodes S, Jammali-Blasi A, Ramsden V, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (May 2021). "Beds, overlays and mattresses for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5) CD013624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013624.pub2. PMC 8108042. PMID 33969896.

- ^ Guy H (December 2004). "Preventing pressure ulcers: choosing a mattress". Professional Nurse. 20 (4): 43–46. PMID 15624622.

- ^ "Antidecubitus Why?" (PDF). Antidecubitus Systems Matfresses Cushions. COMETE s.a.s. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ^ Bain DS, Ferguson-Pell M (2002). "Remote monitoring of sitting behavior of people with spinal cord injury". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 39 (4): 513–520. PMID 17638148.

- ^ Shi C, Dumville JC, Cullum N, Rhodes S, McInnes E, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (May 2021). "Foam surfaces for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5) CD013621. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013621.pub2. PMC 8179968. PMID 34097765.

- ^ Shi C, Dumville JC, Cullum N, Rhodes S, McInnes E, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (May 2021). "Alternative reactive support surfaces (non-foam and non-air-filled) for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5) CD013623. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013623.pub2. PMC 8179967. PMID 34097764.

- ^ Shi C, Dumville JC, Cullum N, Rhodes S, Leung V, McInnes E, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (May 2021). "Reactive air surfaces for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5) CD013622. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013622.pub2. PMC 8127698. PMID 33999463.

- ^ Shi C, Dumville JC, Cullum N, Rhodes S, McInnes E, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (May 2021). "Alternative reactive support surfaces (non-foam and non-air-filled) for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5) CD013623. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013623.pub2. PMC 8179967. PMID 34097764.

- ^ a b Stephens M, Bartley C, Dumville JC, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (February 2022). "Pressure redistributing static chairs for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (2) CD013644. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013644.pub2. PMC 8851035. PMID 35174477.

- ^ Brienza D, Kelsey S, Karg P, Allegretti A, Olson M, Schmeler M, et al. (December 2010). "A randomized clinical trial on preventing pressure ulcers with wheelchair seat cushions". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 58 (12): 2308–2314. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03168.x. PMC 3065866. PMID 21070197.

- ^ Langer G, Wan CS, Fink A, Schwingshackl L, Schoberer D, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (February 2024). "Nutritional interventions for preventing and treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2024 (2) CD003216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003216.pub3. PMC 10860148. PMID 38345088.

- ^ Khojastehfar S, Najafi Ghezeljeh T, Haghani S (May 2020). "Factors related to knowledge, attitude, and practice of nurses in intensive care unit in the area of pressure ulcer prevention: A multicenter study". Journal of Tissue Viability. 29 (2): 76–81. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2020.02.002. PMID 32061501. S2CID 211136134.

- ^ Heywood-Everett S, Henderson R, Webb C, Bland AR (July 2023). "Psychosocial factors impacting community-based pressure ulcer prevention: A systematic review" (PDF). International Journal of Nursing Studies. 146 104561. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104561. PMID 37542960. S2CID 259523857.

- ^ Moore ZE, Patton D (January 2019). "Risk assessment tools for the prevention of pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD006471. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006471.pub4. PMC 6354222. PMID 30702158.

- ^ Moore ZE, Webster J, Samuriwo R (September 2015). "Wound-care teams for preventing and treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9) CD011011. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011011.pub2. PMC 8627699. PMID 26373268.

- ^ Porter-Armstrong AP, Moore ZE, Bradbury I, McDonough S (May 2018). "Education of healthcare professionals for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (5) CD011620. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011620.pub2. PMC 6494581. PMID 29800486.

- ^ O'Connor T, Moore ZE, Patton D (February 2021). "Patient and lay carer education for preventing pressure ulceration in at-risk populations". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2) CD012006. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012006.pub2. PMC 8095034. PMID 33625741.

- ^ a b Patton D, Moore ZE, Boland F, Chaboyer WP, Latimer SL, Walker RM, et al. (December 2024). "Dressings and topical agents for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2024 (12) CD009362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009362.pub4. PMC 11613325. PMID 39625073.

- ^ Zhang Q, Sun Z, Yue J (June 2015). "Massage therapy for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (6) CD010518. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010518.pub2. PMC 9969327. PMID 26081072.

- ^ "Hill-Rom Clinical Resource Center". Archived from the original on 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- ^ Langer G, Fink A (June 2014). "Nutritional interventions for preventing and treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (6) CD003216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003216.pub2. PMC 9736772. PMID 24919719.

- ^ "510(k)s Final Decisions Rendered for January 2004: Device: Medical Maggots". FDA. Archived from the original on 2009-01-20. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- ^ a b Westby MJ, Dumville JC, Soares MO, Stubbs N, Norman G (June 2017). "Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6) CD011947. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011947.pub2. PMC 6481609. PMID 28639707.

- ^ Sipponen A, Jokinen JJ, Sipponen P, Papp A, Sarna S, Lohi J (May 2008). "Beneficial effect of resin salve in treatment of severe pressure ulcers: a prospective, randomized and controlled multicentre trial". The British Journal of Dermatology. 158 (5): 1055–1062. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08461.x. PMID 18284391. S2CID 12350060.

- ^ Westby MJ, Dumville JC, Soares MO, Stubbs N, Norman G (June 2017). "Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6) CD011947. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011947.pub2. PMC 6481609. PMID 28639707.

- ^ Dumville JC, Keogh SJ, Liu Z, Stubbs N, Walker RM, Fortnam M (May 2015). "Alginate dressings for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (5) CD011277. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011277.pub2. hdl:10072/81471. PMC 10555387. PMID 25994366.

- ^ Walker RM, Gillespie BM, Thalib L, Higgins NS, Whitty JA (October 2017). "Foam dressings for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (10) CD011332. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011332.pub2. PMC 6485618. PMID 29025198.

- ^ Dumville JC, Stubbs N, Keogh SJ, Walker RM, Liu Z (February 2015). Dumville JC (ed.). "Hydrogel dressings for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (2) CD011226. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011226. hdl:10072/81469. PMC 10767619. PMID 25914909.

- ^ DeMarco S. "Wound and Pressure Ulcer Management". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- ^ Naing C, Whittaker MA (June 2017). "Anabolic steroids for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (6) CD011375. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011375.pub2. PMC 6481474. PMID 28631809.

- ^ Papanikolaou GE, Gousios G, Cremers NA (March 2023). "Use of Medical-Grade Honey to Treat Clinically Infected Heel Pressure Ulcers in High-Risk Patients: A Prospective Case Series". Antibiotics. 12 (3): 605. doi:10.3390/antibiotics12030605. PMC 10044646. PMID 36978472.

- ^ Shi J, Gao Y, Tian J, Li J, Xu J, Mei F, et al. (May 2023). "Negative pressure wound therapy for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (5) CD011334. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011334.pub3. PMC 10218975. PMID 37232410.

- ^ Chen C, Hou WH, Chan ES, Yeh ML, Lo HL (July 2014). "Phototherapy for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (7) CD009224. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009224.pub2. PMC 11602825. PMID 25019295.

- ^ McGinnis E, Stubbs N (February 2014). "Pressure-relieving devices for treating heel pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (2) CD005485. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005485.pub3. PMC 10998287. PMID 24519736.

- ^ Norman G, Wong JK, Amin K, Dumville JC, Pramod S (October 2022). "Reconstructive surgery for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (10) CD012032. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012032.pub3. PMC 9562145. PMID 36228111.

- ^ McInnes E, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SE, Leung V (October 2018). "Support surfaces for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10) CD009490. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009490.pub2. PMC 6517160. PMID 30307602.

- ^ Baba-Akbari Sari A, Flemming K, Cullum NA, Wollina U (July 2006). "Therapeutic ultrasound for pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3) CD001275. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001275.pub2. PMID 16855964.

- ^ Hao XY, Li HL, Su H, Cai H, Guo TK, Liu R, et al. (February 2017). "Topical phenytoin for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (2) CD008251. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008251.pub2. PMC 6464402. PMID 28225152.

- ^ Arora M, Harvey LA, Glinsky JV, Nier L, Lavrencic L, Kifley A, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (January 2020). "Electrical stimulation for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD012196. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012196.pub2. PMC 6984413. PMID 31962369.

- ^ Norman G, Dumville JC, Moore ZE, Tanner J, Christie J, Goto S (April 2016). "Antibiotics and antiseptics for pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4) CD011586. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011586.pub2. PMC 6486293. PMID 27040598.

- ^ Langer G, Wan CS, Fink A, Schwingshackl L, Schoberer D, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (February 2024). "Nutritional interventions for preventing and treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2024 (2) CD003216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003216.pub3. PMC 10860148. PMID 38345088.

- ^ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. "Preventing Pressure Ulcers in Hospitals". Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ "Pressure ulcers in America: prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. An executive summary of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel monograph". Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 14 (4): 208–215. 2001. doi:10.1097/00129334-200107000-00015. PMID 11902346.

- ^ Vanderwee K, Clark M, Dealey C, Gunningberg L, Defloor T (April 2007). "Pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study". Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 13 (2): 227–235. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00684.x. PMID 17378869.

- ^ Anthony D, Papanikolaou P, Parboteeah S, Saleh M (November 2010). "Do risk assessment scales for pressure ulcers work?". Journal of Tissue Viability. 19 (4): 132–136. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2009.11.006. PMID 20036124.

- ^ Li Y, Yin J, Cai X, Temkin-Greener J, Mukamel DB (July 2011). "Association of race and sites of care with pressure ulcers in high-risk nursing home residents". JAMA. 306 (2): 179–186. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.942. PMC 4108174. PMID 21750295.

Further reading

[edit]- Lyder CH, Ayello EA (April 2008). "Pressure Ulcers: A Patient Safety Issue". In Hughes RG (ed.). Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Advances in Patient Safety. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). PMID 21328751.

- Qaseem A, Mir TP, Starkey M, Denberg TD (March 2015). "Risk assessment and prevention of pressure ulcers: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (5): 359–369. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.680.8432. doi:10.7326/M14-1567. PMID 25732278. S2CID 17794475.

External links

[edit] Media related to Pressure ulcers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pressure ulcers at Wikimedia Commons

Pressure ulcer

View on GrokipediaHistory and Terminology

Historical Recognition and Evolution

Pressure ulcers, also known as decubitus ulcers or bedsores, were first evidenced in ancient Egyptian mummies dating back approximately 5,000 years, indicating early recognition of tissue damage from prolonged immobilization.[9] In ancient Greece, Hippocrates (circa 460–370 BC) described sores developing in patients who lay in the same posture for extended periods, noting their difficulty to heal, and recommended treatments including warm water washes, vinegar sponging, excision, and poultice application.[10][11] These early observations linked the condition primarily to immobility in the infirm or paralyzed, such as those with paraplegia, but lacked a mechanistic understanding beyond surface-level associations.[12] During the Renaissance and into the 18th century, medical texts continued to document decubitus ulcers in bedridden patients, often viewing them as inevitable complications of chronic illness or injury, with treatments focusing on local care like cleaning and bandaging rather than prevention.[13] In the 19th century, French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot advanced classification by distinguishing acute decubitus (decubitus acutus, rapidly forming post-injury) from chronic forms, but attributed causation to central nervous system damage via "neurotrophic fibers" rather than mechanical pressure, deeming severe cases (decubitus ominosus) ominous and largely unavoidable.[14][15] This neurotrophic theory dominated, influencing perceptions that ulcers signaled poor prognosis in conditions like spinal cord injury, as observed in high incidences among paralyzed soldiers during the American Civil War.[16] The 20th century marked a pivotal evolution toward causal realism, emphasizing prolonged pressure-induced ischemia over neural trophism, with evidence from World War I spinal injury cases highlighting modifiable factors like positioning.[17] British nurse Doreen Norton’s 1950s research demonstrated that regular patient turning prevented ulcers, challenging inevitability and shifting focus to proactive interventions such as repositioning and support surfaces.[18] By the late 20th century, epidemiological studies confirmed prevalence rates of 3–11% in acute care and higher in long-term settings, underscoring prevention's role in reducing morbidity, with management evolving to include multidisciplinary approaches addressing shear, friction, and nutrition alongside pressure relief.[19][20] This progression reflected growing empirical validation of mechanical etiology, diminishing reliance on outdated neural theories.Terminology Shifts and Definitions

Historically, pressure ulcers have been referred to by various terms reflecting observed associations with patient positioning and tissue damage, including "bedsores," originating from their frequent occurrence in prolonged bed rest scenarios, and "decubitus ulcers," derived from the Latin term for lying down, emphasizing dependency on gravity and immobility.[21][22] Over time, "pressure sores" and "pressure ulcers" gained prominence to highlight the primary mechanical etiology of sustained pressure leading to ischemia, rather than solely positional factors.[1][23] In April 2016, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), now known as the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP), revised its terminology from "pressure ulcer" to "pressure injury" to encompass a broader spectrum of damage, including cases involving intact skin without ulceration, such as non-blanchable erythema indicative of early tissue injury.[24][25] This shift addressed limitations in the prior term "ulcer," which implied epithelial breakdown and an open wound, potentially underrepresenting closed injuries from pressure, shear, or friction over bony prominences or medical devices.[26][27] The current definition of a pressure injury, as adopted by the NPIAP, describes it as "localized damage to the skin and/or underlying soft tissue usually over a bony prominence or related to a medical or other device," which may manifest as intact skin, an open ulcer, or deeper tissue involvement and is often painful, with occurrence resulting from prolonged pressure-induced hypoperfusion.[28][29] While "pressure ulcer" remains in use, particularly in European contexts, "pressure injury" predominates in North America, Australia, and Asia for its precision in staging and clinical documentation, facilitating earlier detection and intervention.[30][31]Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Pressure ulcers typically present with localized damage to the skin and underlying tissues, often over bony prominences, manifesting as changes in skin integrity, color, temperature, or texture, along with possible pain or discomfort. Early signs include non-blanchable erythema (redness that persists upon pressure release), which may appear differently on darker skin tones as purple or maroon discoloration, accompanied by firmness, warmth, or coolness compared to adjacent areas.[1] Advanced stages involve tissue loss, ulceration, exudate, and potential infection indicators such as foul odor, increased drainage, swelling, or systemic symptoms like fever if sepsis develops.[2] Pain is common but may be absent in individuals with neuropathy or advanced disease. The National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) classifies pressure ulcers into stages based on depth of tissue damage, guiding symptom recognition:- Stage 1: Intact skin with a localized area of non-blanchable erythema; on darker skin, it may present as persistent purple or maroon discoloration or blood-filled blister due to underlying tissue damage. The area may feel boggy, firm, painful, or warmer/cooler than surrounding tissue.[1]

- Stage 2: Partial-thickness skin loss of the epidermis and/or dermis, appearing as a shallow open ulcer with a red-pink wound bed without slough, or an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Pain and tenderness are often present.[1]

- Stage 3: Full-thickness skin loss with visible subcutaneous fat, potentially undermining or tunneling; granulation tissue may be present, with slough not obscuring the depth. The ulcer extends into but not through underlying fascia, often with moderate to large exudate and associated pain.[1]

- Stage 4: Full-thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon, or muscle; slough or eschar may be present, and the wound may include undermining, tunneling, or epithelial islands. Dead tissue, infection signs, and severe pain are common unless masked by neuropathy.[1]

Complications

Infection represents the primary complication of pressure ulcers, particularly in stages 3 and 4, where necrotic tissue and disrupted skin barriers facilitate bacterial invasion by pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and anaerobes.[1] Local progression often manifests as cellulitis, abscesses, undermining, sinus tracts, or fistulas, exacerbating tissue destruction and delaying healing. Osteomyelitis, a bone infection underlying the ulcer, develops in approximately one-third of stage IV cases, commonly affecting the sacrum, ischium, or trochanter due to contiguous spread from soft tissue necrosis.[32] Diagnosis typically requires imaging like MRI or bone biopsy, as clinical signs alone are unreliable.[33] Systemic complications arise when infection disseminates, leading to bacteremia, sepsis, endocarditis, meningitis, or septic arthritis. Septicemia accounts for 39.7% of pressure ulcer-associated deaths, with nearly 80% occurring in individuals aged 75 years or older.[34] Untreated osteomyelitis heightens risks of chronic bone necrosis and recurrent sepsis, potentially necessitating amputation in extremity ulcers.[35] Mortality is markedly elevated; hospitalized elderly patients with pressure injuries exhibit a 6-month mortality rate of 77%, compared to 18% in those without.[36] In septic shock cohorts, pressure ulcers independently raise 28-day mortality risk by 30% after covariate adjustment.[37] Rare but severe sequelae include Marjolin's ulcer, a squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic wounds, and amyloidosis from prolonged inflammation. Myiasis (maggot infestation) can also occur in neglected pressure ulcers, where untreated necrosis, bacterial infection, poor hygiene, and immobility in unsanitary conditions facilitate fly egg-laying in open wounds, leading to larval tissue infestation.[38] Complications prolong hospital stays by an average of 5-10 days and inflate costs by thousands per case, driven by intensive antimicrobial therapy, debridement, and reconstructive surgery.[39] Early intervention mitigates these risks, as advanced ulcers correlate with two-fold higher overall mortality odds.[36]Etiology and Risk Factors

Primary Causes

Pressure ulcers develop primarily from sustained extrinsic mechanical forces that impair tissue perfusion and cause cellular deformation, most commonly prolonged pressure over bony prominences such as the sacrum, ischial tuberosities, greater trochanters of the hips, and heels.[1] These sites are particularly vulnerable in individuals with prolonged immobility, such as bedridden patients or wheelchair users, where sustained pressure in lying or sitting positions impairs circulation in the hip region and sacral area. This pressure compresses underlying microvasculature, exceeding the capillary closing pressure (typically 15-32 mmHg), leading to ischemia and subsequent tissue necrosis if unrelieved for periods as short as 2 hours in vulnerable individuals. Experimental studies confirm that interface pressures above 60 mmHg for over 2 hours disrupt oxidative metabolism in muscle cells before skin involvement, explaining the depth of injury often observed.[40] Shear stress, a parallel force acting on tissues during sliding or repositioning, exacerbates ischemia by elongating and distorting blood vessels, reducing their lumen and promoting thrombosis even at lower perpendicular pressures.[1] Superficial shear contributes to epidermal stripping, while deeper shear strains, often reaching 1000-2000 Pa in supine positions, predominantly drive full-thickness injuries by combining with pressure to collapse perforating vessels.[40] Friction, generated by skin-surface dragging, causes direct superficial trauma and indirectly amplifies shear, though it rarely penetrates beyond the dermis without concurrent pressure. Moisture from incontinence or perspiration macerates the stratum corneum, reducing its tensile strength and increasing susceptibility to frictional damage, but it functions more as an aggravating factor than a standalone cause.[1] Ischemia-reperfusion cycles upon pressure relief further contribute via oxidative stress and inflammation, perpetuating damage in recurrent episodes, as evidenced in animal models showing histological changes akin to deep tissue injury.[41] These mechanical etiologies underscore that pressure ulcers are not solely ischemic but involve multifaceted tissue distortion, with prevention targeting load redistribution to maintain perfusion above critical thresholds.[40]Modifiable and Non-Modifiable Risk Factors

Non-modifiable risk factors for pressure ulcers encompass intrinsic patient characteristics that cannot be readily altered, such as advanced age, which correlates with dermal thinning, reduced collagen content, and diminished subcutaneous fat, thereby decreasing tissue resilience to sustained pressure.[42][43] Diabetes mellitus represents another key non-modifiable factor, as hyperglycemia impairs microcirculation, neuropathy reduces sensory feedback, and delayed healing exacerbates tissue breakdown under ischemic conditions.[44][45] Chronic conditions like peripheral vascular disease and a history of prior pressure ulcers further elevate susceptibility by compromising baseline perfusion and indicating inherent tissue vulnerability.[46][47] Modifiable risk factors involve extrinsic or behavioral elements amenable to intervention, including limited mobility and immobility, which concentrate pressure on bony prominences and can be mitigated through regular repositioning and support surfaces.[48][49] Inadequate nutritional status and hydration, such as hypoalbuminemia, protein deficiency, or dehydration from insufficient fluid intake, hinders collagen synthesis and immune response, but can be addressed via dietary supplementation and monitoring.[48] Excessive moisture from incontinence or perspiration softens the stratum corneum, increasing shear susceptibility, while interventions like barrier creams and absorbent products reduce this risk.[49] Low hemoglobin levels and vasopressor use, often linked to acute illness, impair oxygen delivery but may be optimized through transfusion or hemodynamic management where feasible.[50]| Category | Examples | Key Mechanisms | Potential Interventions (for Modifiable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Modifiable | Advanced age (>75 years), diabetes, vascular disease, prior ulcers | Reduced tissue tolerance, neuropathy, poor perfusion | None directly; focus on monitoring |

| Modifiable | Immobility, malnutrition/dehydration, incontinence, low BMI | Pressure concentration, impaired healing, skin maceration | Repositioning, nutrition therapy, moisture management |

Pathophysiology

Core Mechanisms

Prolonged mechanical pressure on soft tissues overlying bony prominences is the primary initiator of pressure ulcer formation, compressing microvasculature and impeding blood flow, which leads to localized ischemia and tissue hypoxia. Capillary closing pressure typically occurs at around 32 mmHg, beyond which nutrient delivery ceases and metabolic waste accumulates, triggering anaerobic metabolism and cellular acidosis within 2-4 hours of sustained exposure.[51][1] Shear forces, arising from the sliding or dragging of tissues parallel to the skin surface, exacerbate ischemia by elongating and distorting blood vessels, particularly in deeper tissues where muscle layers are vulnerable to deformation. Unlike perpendicular pressure, shear amplifies strain on vessel walls, reducing tolerance to even moderate loads and contributing to earlier onset of hypoperfusion; studies indicate that combined pressure and shear can halve the time to ischemia compared to pressure alone.[40][52] Upon intermittent relief of pressure, reperfusion paradoxically induces further damage through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which overwhelm antioxidant defenses and activate inflammatory cascades, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) that degrade extracellular matrix and collagen. This oxidative stress and protease activity propagate necrosis from muscle toward the skin surface in deep tissue injuries, often manifesting as purple or maroon discoloration before epidermal breakdown.[53][54] Direct cellular deformation from sustained strain also induces mechanotransductive signaling, promoting apoptosis via pathways like caspase activation, independent of ischemia in some models, though evidence suggests this synergizes with hypoxic effects to lower the pressure threshold for injury. Friction, while more superficial, abrades the stratum corneum and exposes underlying dermis to shear, but its role is secondary to pressure and shear in full-thickness ulcers.[51][52]Tissue-Specific Vulnerabilities and Sites

Pressure ulcers predominantly develop over bony prominences where soft tissues, including skin, subcutaneous fat, and muscle, are subjected to sustained mechanical compression between the bone and an external surface, leading to localized ischemia. The sacrum represents the most frequent site, accounting for approximately 30-40% of cases in hospitalized patients, followed by the heels, which are particularly vulnerable due to limited soft tissue coverage. Other common locations include the ischial tuberosities, greater trochanters, elbows, and occiput, with distribution varying by patient positioning—supine patients more often affected at the sacrum and heels, while seated individuals experience higher incidence at the ischia.[55][2][1] Among affected tissues, skeletal muscle exhibits greater susceptibility to pressure-induced damage than overlying skin, as evidenced by experimental models demonstrating initial pathologic changes in muscle after periods of ischemia that spare superficial layers. This vulnerability arises from muscle's higher metabolic demand, with oxygen consumption rates up to 20 times that of skin under normal conditions, rendering it less tolerant to capillary occlusion pressures exceeding 32 mmHg, which halt nutritive blood flow. Subcutaneous fat provides some cushioning but offers minimal protection in areas of thin coverage, while direct deformation and shear forces exacerbate deep tissue injury by distorting cellular structures and impairing microcirculation independently of overt pressure.[56][57][58] In clinical observations, damage often propagates from muscle to skin, with necrosis visible superficially only after deeper tissues have undergone hours of hypoxia, underscoring the importance of monitoring at-risk sites for early signs like induration or warmth prior to ulceration. Factors such as tissue microclimate, including moisture and temperature, further modulate vulnerability by altering friction and perfusion, though mechanical loading remains the primary causal driver across sites.[1][59]Secondary Contributors

Shear forces and friction act as secondary mechanical contributors, distorting tissue layers and vessels parallel to the skin surface, which compounds ischemic damage by further occluding microcirculation and promoting superficial epidermal stripping.[24] Shear, generated during patient repositioning or slouching, can tear capillaries and reduce tissue tolerance to pressure, leading to deeper ulceration even at lower compressive loads.[60] Friction exacerbates this by abrading the stratum corneum, increasing vulnerability to infection and shear propagation into subcutaneous layers.[1] Moisture from sources such as urinary or fecal incontinence macerates the skin, reducing its tensile strength and amplifying friction and shear effects, thereby accelerating breakdown over bony prominences.[24] This hydration alters the skin's barrier function, facilitating microbial invasion and inflammatory escalation beyond primary ischemia.[60] Reperfusion injury upon pressure relief introduces oxidative stress via reactive oxygen species, endothelial dysfunction, and neutrophil activation, enlarging the necrotic zone and transitioning acute damage to chronic non-healing wounds.[24] [1] Inflammatory mediators, including cytokines like TNF-alpha and IL-6 released in response to hypoxic cell death, sustain a catabolic state that impairs collagen synthesis and angiogenesis, perpetuating tissue destruction independently of ongoing mechanical insult.[1] These cascades can be intensified by comorbidities such as malnutrition or vascular insufficiency, which diminish reparative capacity at the cellular level.[24]Diagnosis

Clinical Assessment

Clinical assessment of pressure ulcers, also known as pressure injuries, relies primarily on history-taking and physical examination to identify the presence, extent, and potential complications of the lesion, with diagnosis confirmed through observable tissue damage rather than routine imaging or laboratory tests unless infection or deeper involvement is suspected.[1] High-risk areas such as the sacrum, heels, ischial tuberosities, and greater trochanters should be systematically inspected, as these bony prominences are prone to sustained pressure leading to ischemia.[1] Assessment should occur upon admission, after episodes of hemodynamic instability, and with any change in condition, emphasizing early detection of non-blanchable erythema indicative of stage 1 injury.[61] Patient history includes evaluating the duration and degree of immobility, such as from paraplegia, stroke, or prolonged hospitalization, alongside comorbidities like diabetes, malnutrition, or vascular insufficiency that exacerbate tissue vulnerability.[1] Inquire about symptom progression, including changes in ulcer size, presence of exudate or foul odor suggesting infection, and associated pain, which may signal deeper involvement despite limited sensory perception in some patients.[1] Nutritional and hydration status, cognitive function, and recent interventions like surgery or sedation are also documented, as deficits in these areas correlate with delayed healing and higher ulcer severity.[1] Physical examination entails measuring the ulcer's length, width, and depth using standardized techniques, such as probing with a sterile swab to detect undermining, tunneling, or sinus tracts, while noting the character of the wound bed (e.g., necrotic eschar, granulation tissue, or slough).[1] Surrounding intact skin is evaluated for erythema, warmth, induration, hardness, swelling, or clinical infection signs, with muscle tissue potentially appearing ischemic prior to overt skin breakdown, complicating depth gauging.[62][1] Drainage type and volume are assessed, alongside palpation for fluctuance or crepitus indicating abscess or gas-forming infection.[62] Pain assessment, using validated scales like the Numeric Rating Scale, is integral, particularly in patients with intact sensation, as escalating pain may precede visible deterioration.[1] While risk scales such as the Braden Scale (scoring sensory perception, mobility, activity, moisture, nutrition, and friction/shear, with scores ≤18 indicating elevated risk) inform overall evaluation, clinical judgment supersedes tool outputs for confirming ulcer presence and guiding staging.[1] Suspected deep tissue or systemic involvement warrants adjunctive tests like wound cultures or radiographs, but these are not routine for initial clinical diagnosis.[1]Classification Systems

The primary classification system for pressure injuries is the international staging framework developed collaboratively by the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP), the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA), with the 2016 revision by NPIAP updating terminology from "pressure ulcer" to "pressure injury" and refining categories to reflect tissue damage depth.[25][63] This system categorizes injuries into six distinct stages based on observable clinical features, such as extent of skin and tissue loss, presence of slough or eschar, and underlying damage indicators, facilitating standardized assessment, communication among clinicians, and guidance for treatment escalation.[63] Staging requires cleansing of the wound bed for accurate visualization and should account for variations in presentation, including challenges in detecting early signs on darker skin tones through non-visual cues like temperature, firmness, or pain.[25][63]| Stage/Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 Pressure Injury | Intact skin with non-blanchable erythema over a bony prominence or related to a device, often painful, firm, soft, warmer, or cooler than adjacent tissue; may appear as persistent red, blue, or purple hues in darker skin tones.[25][63] |

| Stage 2 Pressure Injury | Partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer or intact/ruptured serum-filled blister; wound bed appears pink/red and moist, without slough.[25][63] |

| Stage 3 Pressure Injury | Full-thickness skin loss with damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue, extending to but not through underlying fascia; subcutaneous fat may be visible, with possible undermining, tunneling, slough, or granulation tissue.[25][63] |

| Stage 4 Pressure Injury | Full-thickness skin and tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon, or muscle; slough or eschar may be present, often with undermining and tunneling, and possible osteomyelitis or systemic infection.[25][63] |

| Unstageable Pressure Injury | Full-thickness skin and tissue loss obscured by slough, eschar, or adherent devitalized tissue, preventing depth assessment until debridement occurs (except dry heel eschar, which may be left intact).[25][63] |

| Deep Tissue Pressure Injury | Persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon, or purple discoloration, or blood-filled blister due to underlying muscle or soft tissue damage, often over bony prominences; may evolve rapidly to more severe stages.[25][63] |

Differential Considerations