Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

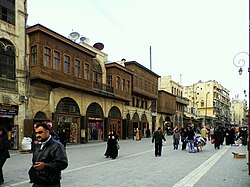

Pedestrian zone

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

Pedestrian zones (also known as auto-free zones and car-free zones, as pedestrian precincts in British English,[1] and as pedestrian malls in the United States and Australia) are areas of a city or town restricted to use by people on foot or human-powered transport such as bicycles, with non-emergency motor traffic not allowed. Converting a street or an area to pedestrian-only use is called pedestrianisation.

Pedestrianisation usually aims to provide better accessibility and mobility for pedestrians, to enhance the amount of shopping and other business activities in the area or to improve the attractiveness of the local environment in terms of aesthetics, air pollution, noise and crashes involving motor vehicles with pedestrians.[2] In some cases, motor traffic in surrounding areas increases, as it is displaced rather than replaced.[2] Nonetheless, pedestrianisation schemes are often associated with significant falls in local air and noise pollution[2] and in accidents, and frequently with increased retail turnover and increased property values locally.[3]

A car-free development generally implies a large-scale pedestrianised area that relies on modes of transport other than the car, while pedestrian zones may vary in size from a single square to entire districts, but with highly variable degrees of dependence on cars for their broader transport links.

Pedestrian zones have a great variety of approaches to human-powered vehicles such as bicycles, inline skates, skateboards and kick scooters. Some have a total ban on anything with wheels, others ban certain categories, others segregate the human-powered wheels from foot traffic, and others still have no rules at all. Many Middle Eastern kasbahs have no motorized traffic, but use donkey- or hand-carts to carry goods.

History

[edit]Origins in arcades

[edit]

The idea of separating pedestrians from wheeled traffic is an old one, dating back at least to the Renaissance.[4] However, the earliest modern implementation of the idea in cities seems to date from about 1800, when the first covered shopping arcade was opened in Paris.[4] Separated shopping arcades were constructed throughout Europe in the 19th century, precursors of modern shopping malls. A number of architects and city planners, including Joseph Paxton, Ebenezer Howard, and Clarence Stein, in the 19th and early 20th centuries proposed plans to separate pedestrians from traffic in various new developments.[5]

1920s–1970s

[edit]The first "pedestrianisation" of an existing street seems to have taken place "around 1929" in Essen, Germany. This was in Limbecker Straße, a very narrow shopping street that could not accommodate both vehicular and pedestrian traffic.[6] Two other German cities followed this model in the early 1930s, but the idea was not seen outside Germany.[4] Following the devastation of the Second World War a number of European cities implemented plans to pedestrianise city streets, although usually on a largely ad hoc basis, through the early 1950s, with little landscaping or planning.[4] By 1955 twenty-one German cities had closed at least one street to automobile traffic, although only four were "true" pedestrian streets, designed for the purpose.[4] At this time pedestrianisation was not seen as a traffic restraint policy, but rather as a complement[clarification needed] to customers who would arrive by car in a city centre.[4]

Pedestrianisation was also common in the United States during the 1950s and 60s as downtown businesses attempted to compete with new suburban shopping malls. However, most of these initiatives were not successful in the long term, and about 90% have been changed back to motorised areas.[7]

1980s–2010s

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2020) |

In the United States, several pedestrian zones in major tourist areas were successful, such as the renovation of the mall in Santa Monica on Los Angeles' Westside and its relaunch as the Third Street Promenade;[8] the creation of the covered, pedestrian Fremont Street Experience in Downtown Las Vegas;[9] the revival of East 4th Street in Downtown Cleveland;[10] and the new pedestrian zone created in the mid-2010s in New York City including along Broadway (the street) and around Times Square.[11]

COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, some cities pedestrianised more streets to encourage social distancing, and in many cases to provide more space for restaurants to serve food on extended patios. In the United States, New York City closed up to 100 miles (160 km) of streets to cars across the city.[12] In Madrid, Spain, the city pedestrianized 19 kilometres (12 miles) of streets and 235,000 square metres (58 acres) of spaces in total.[13] The COVID-19 pandemic also prompted proposals for radical change in the organisation of the city, in particular in Barcelona, such as the pedestrianisation of the whole city and an inversion of the concept of "sidewalk"; these were two elements of the Manifesto for the Reorganisation of the city, written by architecture and urban theorist Massimo Paolini and signed by 160 academics and 300 architects.[14][15][16]

Definitions and types

[edit]

A pedestrian zone is often limited in scope: for example, a single square or a few streets reserved for pedestrians, within a city where residents still largely get around in cars. A car-free town, city or region may be much larger.

Car free towns, cities and regions

[edit]

A car-free zone is different from a typical pedestrian zone, in that it implies a development largely predicated on modes of transport other than the car.[citation needed]

Examples

[edit]

A number of towns and cities in Europe have never allowed motor vehicles. Archetypal examples are:

- Venice, which occupies many islands in a lagoon, divided by and accessed from canals. Motor traffic stops at the car park at the head of the viaduct from the mainland, and water transport and walking take over from there. However, motor vehicles are allowed on the nearby Lido.

- Zermatt in the Swiss Alps. Most visitors reach Zermatt by a cog railway, and there are pedestrian-only streets, but there are also roads with motor vehicles.

Other examples are:

- Cinque Terre in Italy[citation needed]

- Ghent in Belgium: the pedestrian zone was extended in 2017[17] from 35 to more than 50 hectares (123 acres), one of the largest car-free areas in Europe.

- Pontevedra in Spain, an international model of pedestrianization, almost 50% of the city is pedestrianised.;[18][19]

- The Old Town of Rhodes, where many, if not most, of the streets are too steep and/or narrow for car traffic.[citation needed]

- Mount Athos, an autonomous monastic state under the sovereignty of Greece, does not permit automobiles on its territory. Trucks and work-related vehicles only are in use there.[citation needed]

- The medieval city of Mdina in Malta does not allow automobiles past the city walls. It is known as the "Silent City" because of the absence of motor traffic in the city.[citation needed]

- Sark, an island in the English Channel, is a car-free zone where only bicycles, carriages and tractors are used as transportation.

- Gulangyu, an island off the coast of Xiamen in southeastern China. The only vehicles permitted are small electric buggies and electric government service vehicles.[citation needed]

To assist with transport from the car parks in at the edge of car-free cities, there are often bus stations, bicycle sharing stations, and the like.[citation needed]

Car-free development

[edit]The term car-free development implies a physical change: either built-up or changes to an existing built area.[citation needed]

In a 2010 publication co-authored by Steve Melia, car-free developments are defined as residential or mixed-use areas that typically provide an immediate environment devoid of vehicular traffic, offer little to no parking separated from the residence, and are designed to let residents live without car ownership.[20] This definition, which they distinguish from the more common "low car development", is based mainly on experience in North West Europe,[citation needed] where the movement for car-free development began.[citation needed] Within this definition, three types are identified: the Vauban model[21] (based on Vauban, Freiburg: it is not "carfree", but "parking-space-free" (German: stellplatzfrei) in some streets),[22] the limited access model,[23] and pedestrianised centres with residential populations.[23]

Limited access type

[edit]The more common form of carfree development involves some sort of physical barrier, which prevents motor vehicles from penetrating into a car-free interior. Melia et al.[24][failed verification] describe this as the "limited access" type. In some cases, such as Stellwerk 60 in Cologne, there is a removable barrier, controlled by a residents' organisation. In Amsterdam, Waterwijk is a 6-hectare (15-acre) neighborhood where cars may only access parking areas from the streets that form the edges of the neighborhood; all of the inner areas of the neighborhood are car-free. [25]

Temporary car-free streets

[edit]Many cities close certain streets to automobiles, typically on weekends and especially in warm weather, to provide more urban space for recreation, and to increase foot traffic to nearby businesses. Examples include Newbury Street in Boston, and Memorial Drive in Cambridge, Massachusetts (which is along a river).[citation needed] In some cases, popularity has resulted in streets being permanently closed to cars, including JFK Drive in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco; Griffith Drive in Griffith Park, Los Angeles; and Capel Street in Dublin.[26]

Reception

[edit]Benefits

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (July 2016) |

Several studies have been carried out on European carfree developments. The most comprehensive was conducted in 2000 by Jan Scheurer.[27] Other more recent studies have been made of specific car-free areas such as Vienna's Floridsdorf car-free development.[28]

Car-free developments see very low levels of car use and thus much less traffic on surrounding roads, high rates of walking and cycling, more independent movement and active play for children, and less land used for parking and roads, leaving more available for green or social space. The main benefits found for these developments are low atmospheric emissions, low road accident rates, better-built environmental conditions, and the encouragement of active modes.[citation needed]

Problems and criticism

[edit]

The main problems are related to parking management. Where parking is not controlled in the surrounding area, this often results in complaints from neighbours about overspill parking.[citation needed]

There were calls for traffic to be reinstated in Trafalgar Square, London, after pedestrianization caused noise nuisance for visitors to the National Gallery. The director of the gallery is reported to have blamed pedestrianization for the "trashing of a civic space".[29]

Local shopkeepers may be critical of the effect of pedestrianization on their businesses. Reduced through traffic can lead to fewer customers using local businesses, depending on the environment and the area's dependence on the through traffic.[30]

By region and country

[edit]Europe

[edit]

A large number of European towns and cities have made part of their centres car-free since the early 1960s. These are often accompanied by car parks on the edge of the pedestrianised zone, and, in the larger cases, park and ride schemes.[citation needed]

Armenia

[edit]Northern Avenue, located in the Kentron district of central Yerevan, is a large pedestrian avenue. The avenue was inaugurated in 2007 and is mainly home to residential buildings, offices, luxury shops and restaurants.[31]

Belgium

[edit]In Belgium, Brussels has implemented Europe's largest pedestrian zone (French: Le Piétonnier), in phases starting in 2015; this will cover 50 hectares (120 acres). The area covers much of the historic center within the Small Ring (the ring road built on the site of the 14th-century walls), including the Grand-Place/Grote Markt, the Place de Brouckère/De Brouckèreplein, the Boulevard Anspach/Anspachlaan, and the Place de la Bourse/Beursplein.[32][33]

Denmark

[edit]Central Copenhagen is one of the oldest and largest: it was converted from car traffic into a pedestrian zone in 1962 as an experiment, and is centered on Strøget, which is not a single street but a series of interconnected avenues which create a very large pedestrian zone, although it is crossed in places by streets with vehicular traffic. Most of these zones allow delivery trucks to service the businesses there during the early morning, and street-cleaning vehicles will usually go through these streets after most shops have closed for the night. It has grown in size from 15,800 square metres (3.9 acres) in 1962 to 95,750 square metres (23.66 acres) in 1996.[34]

Germany

[edit]A number of German islands ban or strictly limit the private use of motor vehicles. Heligoland, Hiddensee, and all but two of the East Frisian islands are car-free; Borkum and Norderney have car-free zones and strictly limit automobile use during the summer season and in certain areas, also forbidding travel at night. Some areas provide exceptions for police and emergency vehicles; Heligoland also bans bicycles.[35]

In the early 1980s, the Alternative Liste für Demokratie und Umweltschutz (which later became part of Alliance 90/The Greens) unsuccessfully campaigned to make West Berlin a car-free zone.[citation needed]

Netherlands

[edit]In the Netherlands, the inner city of Arnhem has a pedestrian zone (Dutch: voetgangersgebied) within the boundaries of the following streets and squares: Nieuwe Plein, Willemsplein, Gele Rijdersplein, Looierstraat, Velperbinnensingel, Koningsplein, St. Catharinaplaats, Beekstraat, Walburgstraat, Turfstraat, Kleine Oord, and Nieuwe Oeverstraat.[36]

Rotterdam's city center was almost completely destroyed by German bombing in May 1940.[37] The city decided to build a central shopping street, for pedestrians only, the Lijnbaan, which became Europe's first purpose-built pedestrian street.[37] The Lijnbaan served as a model for many other such streets in the early post-World War II era, such as Warsaw, Prague, Hamburg, and the UK's first pedestrianised shopping precinct in Stevenage in 1959.[37] Rotterdam has since expanded the pedestrian zone to other streets.[38] As of 2018, Rotterdam featured three different types of pedestrian zones: "pedestrian zones", "pedestrian zones, cycling permitted outside of shopping hours", and "pedestrian zones, cycling permitted 24/7".[38] Three exceptions to motor vehicles could apply to specific sections of these three zones, namely: "logistics allowed within window times (5 to 10:30 a.m)", "logistics allowed 24/7", and "commercial traffic allowed during market days".[38]

United Kingdom

[edit]In Britain, shopping streets primarily for pedestrians date back to the thirteenth century. A 1981 study found that many Victorian and later arcades continued to be used. A third of London's 168 precincts at that time had been built before 1939, as were a tenth of the 1,304 precincts in the U.K. as a whole.[39][40]

Early post-1945 new towns carried on the tradition of providing some traffic-free shopping streets. However, in the conversion of traditional shopping streets to pedestrian precincts, Britain started only in 1967 (versus Germany's first conversion in 1929, or the first in the U.S. in 1959). Since then growth was rapid, such that by 1980 a study found that most British towns and cities had a pedestrian shopping precinct; 1,304 in total.[39]

Turkey

[edit]In Istanbul, İstiklal Caddesi is a pedestrian street (except for a historic streetcar that runs along it) and a major tourist draw.[citation needed]

U.S. and Canada

[edit]

Canada

[edit]Some Canadian examples are the Sparks Street Mall area of Ottawa, the Distillery District in Toronto, Scarth Street Mall in Regina, Stephen Avenue Mall in Calgary (with certain areas open to parking for permit holders) and part of Prince Arthur Street and the Gay Village in Montreal. Algonquin and Ward's Islands, parts of the Toronto Islands group, are also car-free zones for all 700 residents. Since summer 2004, Toronto has also been experimenting with "Pedestrian Sundays"[1] in its busy Kensington Market. Granville Mall in Halifax, Nova Scotia was a run-down section of buildings on Granville Street built in the 1840s that was restored in the late 1970s. The area was then closed off to vehicles.[citation needed]

United States

[edit]Downtown pedestrian zones

[edit]In the United States, these zones are commonly called pedestrian malls or pedestrian streets and today are relatively rare, with a few notable exceptions. In 1959, Kalamazoo was the first American city to implement a "pedestrian mall" in its downtown core.[41] This became a method that some cities applied for their downtowns to compete with the growing suburban shopping malls of the time. In the 1960s and 70s, over 200 towns in the United States adopted this approach.[41]

The Downtown Mall in Charlottesville, VA is one of the longest pedestrian malls in the United States, created in 1976 and spanning nine city blocks.[42] A number of streets and malls in New York City are now pedestrian-only, including 6½ Avenue, Fulton Street, parts of Broadway, and a block of 25th Street.[43]

A portion of Third Street in Santa Monica in Greater Los Angeles was converted into a pedestrian mall in the 1960s to become what is now the Third Street Promenade, a very popular shopping district located just a few blocks from the beach and Santa Monica Pier.[citation needed]

Lincoln Road in Miami Beach, which had previously been a shopping street with traffic, was converted into a pedestrian only street in 1960. The designer was Morris Lapidus. Lincoln Road Mall is now one of the main attractions in Miami Beach.[citation needed]

The idea of exclusive pedestrian zones lost popularity through the 1980s and into the 1990s and results were generally disappointing, but are enjoying a renaissance with the 1989 renovation and relaunch of the Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica, California,[8] the 1994-5 Fremont Street Experience in Las Vegas and recent pedestrianization of various streets in New York City.[9] These pedestrian zones were more closely tied to the success of retail than in Europe, and by the 1980s, most did not succeed competing with ever more elaborate enclosed malls. Almost all of this generation of pedestrian malls built from 1959 through to the 1970s, have disappeared, or were shrunk down in the 1990s at the request of the retailers. Half of Kalamazoo's pedestrian mall[when?] has been converted into a regular street with auto traffic, though with wide sidewalks.[44]

Outside large cities

[edit]

Mackinac Island, between the upper and lower peninsulas of Michigan, banned horseless carriages in 1896, making it auto-free. The original ban still stands, except for emergency vehicles.[45] Travel on the island is largely by foot, bicycle, or horse-drawn carriage. An 8-mile (13 km) road, M-185 rings the island, and numerous roads cover the interior. M-185 is the only highway in the United States without motorized vehicles.[citation needed] Fire Island in Suffolk County, New York is pedestrianised east of the Fire Island Lighthouse and west of Smith Point County Park (with the exception of emergency vehicles).[citation needed]

Supai, Arizona, located within the Havasupai Indian Reservation is entirely car-free, the only community in the United States where mail is still carried out by mule. Supai is located eight miles from the nearest road, and is accessible only by foot, horse/mule, or helicopter.[citation needed]

Culdesac Tempe, a 17-acre (0.069 square kilometers) car-free district in Tempe, Arizona, is intended to be the nation's first market-rate rental apartment district to ban its tenants from owning cars. Bikes and emergency vehicles are allowed. It has received significant investments from executives at Lyft and Opendoor.[46][47]

Latin America

[edit]Argentina

[edit]

Argentina's big cities, Córdoba, Mendoza and Rosario, have lively pedestrianised street centers (Spanish: peatonales) combined with town squares and parks which are crowded with people walking at every hour of the day and night.[citation needed]

In Buenos Aires, some stretches of Calle Florida have been pedestrianised since 1913,[48] which makes it one of the oldest car-free thoroughfares in the world today. Pedestrianised Florida, Lavalle and other streets contribute to a vibrant shopping and restaurant scene where street performers and tango dancers abound, streets are crossed with vehicular traffic at chamfered corners.[citation needed]

Brazil

[edit]

Paquetá Island in Rio de Janeiro is auto-free. The only cars allowed on the island are police and ambulance vehicles. In Rio de Janeiro, the roads beside the beaches are auto-free on Sundays and holidays.[citation needed]

Downtown Rio de Janeiro, Ouvidor Street, over almost its entire length, has been continually a pedestrian space since the mid-nineteenth century when not even carts or carriages were allowed. And the Saara District, also downtown, consists of some dozen or more blocks of colonial streets, off-limits to cars, and crowded with daytime shoppers. Likewise, many of the city's hillside favelas are effectively pedestrian zones as the streets are too narrow and/or steep for automobiles.[citation needed]

Eixo Rodoviário, in Brasília, which is 13 kilometers long and 30 meters wide and is an arterial road connecting the center of that city from both southward and northward wings of Brasília, perpendicular to the well known Eixo Monumental (Monumental Axis in English), is auto-free on Sundays and holidays.[citation needed]

Rua XV de Novembro (15 November Street) in Curitiba is one of the first major pedestrian streets in Brazil.[citation needed]

Chile

[edit]Chile has many large pedestrian streets. An example is Paseo Ahumada and Paseo Estado in Santiago, Paseo Barros Arana in Concepción and Calle Valparaíso in Viña del Mar.[citation needed]

Colombia

[edit]

During his 1998–2001 term, the former Bogotá mayor, U.S.-born Enrique Peñalosa, created several pedestrian streets, plazas and bike paths integrated with a new bus rapid transit system.[citation needed]

The historic center of Cartagena closes some streets to cars during certain hours.[citation needed]

In downtown Armenia, Colombia there is a large pedestrian street where several boutiques are located.[citation needed]

Santa Marta also has permanent pedestrian zones in the historic center around the Cathedral Basílica of Santa Marta.[citation needed]

Mexico

[edit]

The Historic center of Mexico City has 12 pedestrian streets including Madero Street, and as of 30 June 2020, is expanding the number to 42 pedestrian streets.[49] Génova is a busy pedestrian street in the Zona Rosa as is Plaza Garibaldi downtown, where mariachis play.[citation needed]

The old city of Guanajuato is largely pedestrian. The steep and/or narrow side streets were never accessible by cars and most other streets were pedestrianized in the 1960s after through traffic was moved to a system of former flood control tunnels that was no longer necessary due to a new dam.[50]

Playa del Carmen has a pedestrian mall, Quinta Avenida, ("Fifth Avenue") that stretches 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) and receives 4 million visitors annually with hundreds of shops and restaurants.[citation needed]

Peru

[edit]

Jirón de La Unión in Lima is a traditional pedestrian street located in the Historic Centre of Lima, part of the capital of Peru.[citation needed]

In the city of Arequipa, Mercaderes is also a considerably large pedestrian street.[51] Also, recently three of the four streets surrounding the city's main square or "Plaza de Armas" were also made pedestrian.[52]

South and East Asia

[edit]

Mainland China

[edit]Nanjing Road in Shanghai is perhaps the most well-known pedestrian zone in mainland China. Wangfujing is a famous tourist and retail oriented pedestrian zone in Beijing. Chunxilu in Chengdu is the most well known in western China. Dongmen is the busiest business zone in Shenzhen. Zhongyang Street is a historical large pedestrian street in Harbin.[citation needed]

Hong Kong

[edit]

In Hong Kong, since 2000, the government has been implementing full-time or part-time pedestrian streets in a number of areas, including Causeway Bay, Central, Wan Chai, Mong Kok, and Tsim Sha Tsui.[53] The most popular pedestrian street is Sai Yeung Choi Street. It was converted into a pedestrian street in 2003. From December 2008 to May 2009, there were three acid attacks during which corrosive liquids were placed in plastic bottles and thrown from the roof of apartments down onto the street.[citation needed]

India

[edit]Vehicles have been banned in the town of Matheran, in Maharashtra, India since the time it was discovered in 1854.[54]

In India, a citizens' initiative in Goa state, has made 18 June Road, Panjim's main shopping boulevard a Non-Motorised Zone[55](NoMoZo). The road is converted into a NoMoZo for half a day on one Sunday every month.[citation needed]

In Pune, Maharashtra, similar efforts have been made to convert M.G. Road (a.k.a. Main Street) into an open-air mall. The project in question aimed to create a so-called "Walking Plaza".[56]

In May 2019, the North Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) made the busy Ajmal Khan Road in Karol Bagh pedestrian-only.[57]

Church Street in Bangalore went through a pedestrianization process [58]

Japan

[edit]Pedestrian zones in Japan are called hokōsha tengoku (歩行者天国, literally "pedestrian heaven").[citation needed] Clis Road, in Sendai, Japan, is a covered pedestrian mall, as is Hondōri in Hiroshima.[citation needed] Several major streets in Tokyo are closed to vehicles during weekends.[citation needed] One particular temporary hokōsha tengoku in Akihabara was cancelled after the Akihabara massacre in which a man rammed a truck into the pedestrian traffic and subsequently stabbed more than 12 people.[citation needed]

South Korea

[edit]Insadong in Seoul, South Korea has a large pedestrian zone (Insadong-gil) during certain hours.[citation needed]

Also in South Korea, in 2013, in the Haenggun-dong neighbourhood of Suwon, streets were closed to cars as a month-long car-free experiment while the city hosted the EcoMobility World Festival. Instead of cars, residents used non-motorized vehicles provided by the festival organizers.[59] The experiment was not unopposed; however, on balance it was considered a success. Following the festival, the city embarked on discussions about adopting the practice on a permanent basis.[60]

Taiwan

[edit]Ximending in Wanhua District, Taipei is a neighbourhood and shopping district. It was the first pedestrian zone in Taiwan.[61] The district is very popular in Taiwan. In central Taiwan, Yizhong Street is one of the most popular pedestrian shopping area in Taichung. In Southern Taiwan, the most famous pedestrian shopping area is Shinkuchan in Kaohsiung.

Thailand

[edit]In Thailand, some small streets (soi) in Bangkok are designed to be all-time closed to automobile traffic, the city's famous shopping streets of Sampheng Lane in Chinatown and Wang Lang Market nearby to Siriraj Hospital, are the most popular for both local and tourists shopping streets. Additionally the city has built long skywalk systems. Walking Street, Pattaya is also closed to auto traffic. Night markets are routinely closed to auto traffic.[citation needed]

Vietnam

[edit]Huế in Vietnam has made 3 roads into pedestrians-only on weekend nights.[62] Also, Hanoi has opened an Old Quarter Walking Street on weekend nights.[63] Ho Chi Minh City also changed Nguyễn Huệ street into pedestrian zone.[citation needed]

Middle East and North Africa

[edit]North Africa contains some of the largest auto-free areas in the world. Fes-al-Bali, a medina of Fes, Morocco, with its population of 156,000, may be the world's largest contiguous completely carfree area, and the medinas of Cairo, Tunis, Casablanca, Meknes, Essaouira, and Tangier are quite extensive.[citation needed]

In Israel, Tel Aviv has a pedestrian mall, near Nahalat Binyamin Street.[64][65] Ben Yehuda Street in Jerusalem is a pedestrian mall.[66]

Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]

In Australia, as in the US, these zones are commonly called pedestrian malls and in most cases comprise only one street. Most pedestrian streets were created in the late 1970s and 1980s, the first being City Walk, Garema Place in Canberra in 1971. Of 58 pedestrian streets created in Australia in the last quarter of the 20th century, 48 remain today, ten having re-introduced car access between 1990 and 2004.[67] All capital cities in Australia have at least one pedestrian street of which most central are: George Street, Pitt Street Mall and Martin Place in Sydney, Bourke Street Mall in Melbourne, Queen Street Mall and Brunswick Street Mall in Brisbane, Rundle Mall in Adelaide, Hay Street and Murray Street Malls in Perth, Elizabeth Street Mall in Hobart, City Walk in Canberra, and Smith Street in Darwin. Many other mid-sized and regional Australian cities also feature pedestrian malls, examples include Rooke Street Devonport Langtree Avenue Mildura, Cavill Avenue Surfers Paradise, Bridge Street Ballarat, Nicholas Street Ipswich, Hargreaves Street Bendigo, Maude Street Shepparton and Little Mallop Street Geelong.[citation needed]

Empirical studies by Jan Gehl indicate an increase of pedestrian traffic as result of public domain improvements in the centres of Melbourne with 39% increase between 1994 and 2004[68] and Perth with 13% increase between 1993 and 2009.[69]

Most intensive pedestrian traffic flows on a summer weekday have been recorded in Bourke Street Mall Melbourne with 81,000 pedestrians (2004),[68] Rundle Mall Adelaide with 61,360 pedestrians (2002), Pitt Street Mall Sydney with 58,140 (2007) and Murray Street Mall Perth with 48,350 pedestrians (2009).[69]

Rottnest Island off Perth is car-free, only allowing vehicles for essential services. Bicycles are the main form of transport on the island; they can be hired or brought over on the ferry.[citation needed]

In Melbourne's north-eastern suburbs, there have been many proposals to make the Doncaster Hill development area a pedestrian zone. If the proposals are passed, the zone could be one of the largest in the world, by area.[citation needed]

New Zealand

[edit]

Wellington's Cuba Street became the first pedestrian-only street in New Zealand when in 1965 the Wellington tramway lines were removed and the street was closed off to auto traffic, and after public pressure to keep it closed to automobiles, part of the street was pedestrianised in 1969 and reopened as Cuba Mall.[70][71]

New Zealand's second-largest city, Christchurch, made its main shopping streets (Cashel & High Street) pedestrian-only in 1982 and created City Mall, also commonly known as Cashel Mall. The concept was first proposed in 1965, around the same time Wellington proposed Cuba Street's pedestrianisation. After the success of Cuba Mall in Wellington, Christchurch decided to continue with the plans. In 1976 the Bridge of Remembrance was pedestrianised, and eventually in August 1982 the entire City Mall was pedestrianised and fully opened to the public.[70] The area was repaved in the late 2000s and again after the Christchurch Earthquakes in 2010 & 2011.[72]

Queenstown has made most of its town centre a pedestrian zone with the lower part of Ballarat Street converted in the 1970s and turned into Queenstown Mall. Most recently, Lower Beach Street has been partially pedestrianised with now only one-way traffic for cars.[73][74]

Auckland's Lower Queen Street was pedestrianised in 2020.[75][76]

Town Centre–style pedestrian malls rose in popularity in the 1970 & 1980s, springing up around New Zealand after the success of Cuba Mall. Many, however, have since fallen into disrepair and abandonment and are now classified as Dead malls, including Bishopdale Village Mall, Otara Town Centre, and New Brighton Mall. Pedestrian malls are still being built, however much more scarcely and now are usually called Town Centres and have parking on the outskirts, including Rolleston Fields, The Sands Town Centre, and The Landing Wigram.[77][78][79]

A proposal has been made for a pedestrian priority community near Papakura in Auckland. The community would be called Sunfield and cost $4 Billion NZD to build. It is designed to have 4,400 homes and is projected to decrease normal car usage by 90% compared to typical suburbs.[80] It has run into challenges after the project being rejected by Kāinga Ora for fast-tracking following Covid-19; construction authorities took Kāinga Ora to court over the matter.[81][82]

See also

[edit]- Carfree city

- Car-free days

- Car-free movement

- Footpath

- Jan Gehl

- List of car-free places

- Mobility transition

- Living street – Traffic calming in spaces shared between road users

- Pedestrian village – Urban planning for mixed-use areas prioritising pedestrians

- Principles of intelligent urbanism

- Street hierarchy – Urban planning restricting through traffic of automobiles

- Street reclamation – Changing streets to focus on non-car use

- Transit mall – Urban street reserved for public transit, bicycles, and pedestrians

- Urban vitality

References

[edit]- ^ "Pedestrian precinct - Definition, meaning & more - Collins Dictionary". Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Chiquetto, Sergio (1997). "The Environmental Impacts from the Implementation of a Pedestrianization Scheme". Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 2 (2): 133–146. Bibcode:1997TRPD....2..133C. doi:10.1016/S1361-9209(96)00016-8.

- ^ Castillo-Manzano, José; Lopez-Valpuesta, Lourdes; Asencio-Flores, Juan P. (2014). "Extending pedestrianization processes outside the old city center; conflict and benefits in the case of the city of Seville". Habitat International. 44: 194–201. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.06.005. hdl:11441/148812.

- ^ a b c d e f Hall, Peter; Hass-Klau, Carmen (1985). Can Rail Save the City? The impacts of rapid transit and pedestrianisation on British and German cities. Aldershot: Gower Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 978-0566009471.

- ^ Hall, Peter; Hass-Klau, Carmen (1985). Can Rail Save the City? The impacts of rapid transit and pedestrianisation on British and German cities. Aldershot: Gower Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 978-0566009471.

- ^ "Video: Älteste Fußgängerzone Deutschlands wird 90 und befindet sich in Essen - Lokalzeit Ruhr - Sendungen A-Z - Video - Mediathek - WDR". Archived from the original on 22 October 2017.

- ^ Judge, Cole. "The Experiment of American Pedestrian Malls: Trends Analysis, Necessary Indicators for Success and Recommendations for Fresno's Fulton Mall" (PDF). Fresno Future. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ a b Pojani, Dorina (2008). "Santa Monica's Third Street Promenade: the failure and resurgence of a downtown pedestrian mall". Urban Design International. 13 (3): 141–155. doi:10.1057/udi.2008.8. S2CID 108994768.

- ^ a b Pedestrian zones in cities, National Urban League, 2020

- ^ Nickoloff, Annie (22 April 2021). "Exploring East 4th Street: 16 restaurants, shops and venues in the downtown neighborhood". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Torossian, Ronn (14 May 2014). "New York For New Yorkers". New York Observer.

- ^ Spivack, Caroline (27 April 2020). "New York will open up to 100 miles of streets to pedestrians: The move will help New Yorkers socially distance amid the coronavirus pandemic". Curbed.

- ^ Domingo, Marta (7 May 2020). "Madrid peatonalizará 29 calles los fines de semana y festivos y abrirá los parques de los distritos mañana". ABC Madrid.

- ^ Paolini, Massimo (20 April 2020). "Manifesto for the Reorganisation of the City after COVID19". Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Argemí, Anna (8 May 2020). "Por una Barcelona menos mercantilizada y más humana" (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Maiztegui, Belén (18 June 2020). "Manifiesto por la reorganización de la ciudad tras el COVID-19" (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Alleen koppigaards kunnen zo'n circulatieplan doorvoeren". VRT. 1 April 2017.

- ^ "'For me, this is paradise': life in the Spanish city that banned cars". The Guardian. 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ "Pontevedra - How To Ban Cars Downtown". Mike looks at the map. 19 November 2018. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ Melia 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Melia 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Melia 2010, p. 25–26.

- ^ a b Melia 2010, p. 26.

- ^ "WTPP Index - Main Index". Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "Het GWL-terrein: Nederlands eerste duurzame wijk" [The Amsterdam Waterworks Site: The Netherlands' First Sustainable Neighborhood]. GWL Terrein (in Dutch). Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Tu, Maylin (5 December 2022). "These Cities' Car-Free Streets Are Here to Stay". Reasons to be Cheerful. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Scheurer, J. (2001) Urban Ecology, Innovations in Housing Policy and the Future of Cities: Towards Sustainability in Neighbourhood CommunitiesThesis (PhD), Murdoch University Institute of Sustainable Transport.

- ^ Ornetzeder, M., Hertwich, E.G., Hubacek, K., Korytarova, K. and Haas, W. (2008) The environmental effect of car-free housing: A case in Vienna. Ecological Economics 65 (3), 516-530.

- ^ "Trafalgar Square is being trashed, says gallery chief". London Evening Standard. ES London. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ "'They're going to ruin us with the pedestrianization'". WalesOnline. Media Wales. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ "Yerevan Remade: The Case of the Northern Avenue". Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Project. Pedestrian Zone, Brussels city website". Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Feargus (1 May 2019). "In Car-Choked Brussels, the Pedestrians Are Winning". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Reclaiming city streets for people: Chaos or quality of life" (PDF). European Union, Directorate General of the Environment: 16. 13 March 2024.

- ^ "§ 50 Straßenverkehrs-Ordnung". www.gesetze-im-internet.de. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Verordening ontheffingen berijden voetgangersgebied binnenstad Arnhem 2004" [2004 Regulation on exemptions for driving in the pedestrian zone in the inner city of Arnhem]. repository.officiele-overheidspublicaties.nl (in Dutch). 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Renate van der Zee (19 September 2018). "Walk the Lijnbaan: decline and rebirth on Europe's first pedestrianised street". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Overzichtskaart voetgangers- en venstertijdgebieden Centrum Rotterdam" [Overview map of pedestrian and window areas in the centre of Rotterdam] (PDF). Rotterdam city government website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ a b Roberts, J (1981). Pedestrian Precincts in Britain.

- ^ Harrison, Brian (9 September 2011). Finding a Role?: The United Kingdom 1970–1990. Oxford University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-19-254399-8.

- ^ a b Robertson, Kent (1990). "The Status of Pedestrian Malls in American Downtowns". Urban Affairs Quarterly. 26 (2): 250–273. doi:10.1177/004208169002600206. S2CID 154847964.

- ^ "City of Charlottesville Downtown Mall Schematic Design Report" (PDF). Wallace Roberts & Todd LLC. May 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ "Public Plazas". NYC DOT. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Feriel, Cédric (29 May 2013). "Pedestrians, cars and the city". Metropolitics (From opposition to cohabitation).

- ^ "History". Mackinac Island. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Ryan (22 June 2020). "Introducing Culdesac". Medium. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Dougherty, Conor (31 October 2020). "The Capital of Sprawl Gets a Radically Car-Free Neighborhood". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ (in Spanish) Calle Florida History: www.buenosaires.com Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Conoce cuales modificaciones en las calles peatonales de la CDMX” (“Here are the changes in pedestrian streets in Mexico City”), Imagen Radio News, June 30, 2020

- ^ "Some Urban Observations From My Mexico Vacation". Streetsblog. 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Calle Mercaderes - Arequipa, Región Arequipa - Opiniones y fotos - TripAdvisor". Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "Arequipa: Hoy la plaza de armas es solo para los peatones". 21 June 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ Hong Kong Transport Department Website, Transport Department

- ^ Dey, J (19 May 1999). "MMRDA questions council's new designs on Matheran". Mumbai: The Indian Express. Express News. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Down To Earth: Walk this way

- ^ "MG Road walking plaza will be back". The Times of India. November 2011. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "After pedestrianisation, Karol Bagh market area gets park-and-ride facility". Business Standard India. Press Trust of India. 10 October 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Reddy, Y Maheswara (14 April 2023). "Nightmare on Church Street". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ Strother, Jason (30 September 2013). "Locals applaud car-free month in Korean city". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ "Report presents legacy of car-free neighborhood". EcoMobility world Festival 2013. ICLEI. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ "Ximending: A Shopper's Heaven with a Dash of Tradition and Trendiness". Kaohsiung Travel. 11 December 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Vietnam's Hue City formally opens 3 walking streets". October 2017.

- ^ "Hanoi Walking Street - Silkpath". Archived from the original on 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Nachalat Binyamin Market". Touristisrael.com. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ "Nachalat Binyamin Pedestrian Mall". Visit-tel-aviv.com. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ "Ben Yehuda Street". Gojerusalem.com. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Australian Outdoor Pedestrian Mall Survey 2006

- ^ a b Melbourne 'Places for People' Archived 14 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b City of Perth - Public Spaces Public Life Archived 19 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Streets, avenues and pedestrian spaces". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Cuba Street has time on its side". Wellington City Council. 16 September 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Moore, Martin; Heather, Ben (29 October 2011). "Christchurch's City Mall re-opens". Stuff. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Cars to give way to bikes, pedestrians as Lower Beach opens for Xmas". Crux. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Roxburgh, Tracey (23 August 2016). "Street may be pedestrian mall permanently". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Jacobson, Adam (4 October 2017). "Pedestrian-dominated space revealed for lower Queen St". Stuff. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Lower Queen Street pedestrian mall". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Rolleston Fields forever". Metropol. 17 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Auckland's small town of Drury to get a brand new town centre". Summit Homes. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "'Four times the size of Bayfair': Plans for $1b Pāpāmoa East town centre revealed". The New Zealand Herald. 5 December 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Fonseka, Dileepa (31 December 2022). "Winton's $4b Sunfield development: Why efforts to remove red tape are proving so difficult". Stuff. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "5000-home development rejected by Housing Minister for fast-track treatment". The New Zealand Herald. 23 November 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Kāinga Ora hits back over anti-competition claims". Newsroom. 19 December 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Melia, Steve (2010). "Carfree, low-car – What's the Difference?" (PDF). World Transport Policy and Practice 16. 16 (2). Eco-Logica Ltd.: 24–32. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

Pedestrian zone

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Classifications

Core Definition and Principles

A pedestrian zone, also known as a pedestrian precinct or car-free zone, is a public urban space where motor vehicle access is prohibited or severely limited, reserving the area primarily for pedestrians, cyclists, and occasionally other non-motorized uses such as delivery vehicles during restricted hours.[1] This designation transforms streets or plazas into shared environments that prioritize human-scale interactions over vehicular throughput, often featuring widened sidewalks, street furniture, and landscaping to accommodate walking, lingering, and social activities.[12] Such zones emerged as responses to post-World War II urban congestion, with the core intent of reclaiming street space from automobiles to foster safer and more livable city centers.[13] The foundational principles of pedestrian zones emphasize safety through the elimination of vehicle-pedestrian conflicts, which empirical data from implemented zones show reduces injury rates by up to 90% compared to adjacent trafficked streets.[1] Environmentally, these areas lower local air pollution and noise by curtailing exhaust emissions and engine sounds, contributing to measurable improvements in urban air quality metrics in cities like Copenhagen and Freiburg.[14] Economically, the design promotes retail and hospitality vitality by increasing foot traffic and dwell times, with studies indicating average sales uplifts of 20-30% in pedestrianized commercial districts due to enhanced accessibility and ambiance.[15] Accessibility remains a guiding tenet, requiring integration with surrounding transit networks and provisions for diverse users, including those with disabilities, to ensure equitable use without isolating the zone from broader urban mobility.[16] Implementation principles stress clear demarcation via signage, bollards, or paving changes to enforce restrictions, alongside allowances for essential services like emergency access and timed freight deliveries to balance functionality with the car-free ethos.[17] These zones operate on the causal premise that prioritizing non-motorized movement directly enhances social cohesion and public health by encouraging physical activity and reducing sedentary travel patterns.[18]Types and Variations

Pedestrian zones encompass a range of configurations distinguished by the extent of vehicular restriction, scale, and permitted uses. Full pedestrian malls, also known as exclusive pedestrian streets, ban non-emergency motor vehicles entirely, dedicating the space solely to foot traffic, bicycles, and occasional service access; these often feature in commercial districts to enhance retail vitality and safety, with examples including the Church Street Marketplace in Burlington, Vermont, operational since 1981, and the Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica, California, permanently closed to traffic since 1989 after initial trials.[11] [11] Semi-malls represent a partial variation, permitting limited one-way vehicular traffic alongside pedestrians to balance accessibility and priority, typically in linear urban corridors where full closure might disrupt logistics.[19] Transit malls integrate public transportation into pedestrian-dominated spaces, reserving roadways primarily for buses or light rail while prohibiting private vehicles, thereby supporting high-volume transit ridership and pedestrian activity; notable implementations include Nicollet Mall in Minneapolis, Minnesota, established in 1967 as one of the earliest examples, where cross-streets allow limited pedestrian crossings.[20] Shared spaces, or woonerfs—originating in the Netherlands in the 1970s—blur distinctions between roadways and sidewalks through uniform paving, traffic calming, and speed limits capped at walking pace (typically 20 km/h or less), prioritizing pedestrians and cyclists over vehicles to foster social interaction and reduce dominance of cars.[21] [22] These designs eliminate curbs and signage to encourage mutual vigilance among users, as applied in residential or mixed-use streets globally.[21] Larger-scale variations include superblocks, which enclose multiple blocks to restrict through-traffic while allowing localized vehicle access at reduced speeds, exemplified by Barcelona's Poblenou superblock implemented in 2016, part of a plan for 503 such units to minimize emissions and reclaim public space.[11] Temporary or periodic zones offer flexible implementations, closing streets full-time for events or recurring cycles, such as Bogotá's Ciclovía program, which has blocked 76 miles of roads every Sunday and holiday since 1974 to promote recreation.[11] Part-time pedestrian zones, operational during peak hours or seasons, provide adaptability, as in New York City's 14th Street busway, restricted to non-private vehicles from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. since 2019.[11] [23] Across these types, accommodations for human-powered transport like bicycles vary, with some zones enforcing total motor exclusion and others integrating shared paths for inclusivity.[23] ![De Lijnbaan pedestrian mall, Rotterdam]float-rightHistorical Development

Early Precursors and Arcades

Early precursors to dedicated pedestrian zones trace back to ancient urban designs where public spaces prioritized foot traffic, such as the Greek agoras and Roman forums, which functioned as vehicle-free gathering and market areas amid broader street networks shared with carts and animals.[24] In medieval European towns, narrow market streets and squares often restricted wheeled vehicles to facilitate trade and social interaction, though enforcement was informal and horse-drawn transport persisted.[25] These arrangements reflected practical necessities of dense urban life rather than deliberate policy, with pedestrians dominating due to the absence of motorized vehicles. The 19th-century emergence of covered shopping arcades marked a deliberate innovation in pedestrian-exclusive spaces, combining architectural shelter with retail focus to exclude carriages and promote leisurely walking. Originating in Paris during the late 18th century, approximately 150 such passages couverts were constructed by 1850, featuring glass-vaulted ceilings, mosaic floors, and lined boutiques accessible only on foot.[26] Exemplars include the Passage des Panoramas, opened in 1799 as one of the earliest, and Galerie Vivienne, completed in 1823, which provided weather-protected promenades amid Haussmann-era urban growth.[27] In Britain, arcades proliferated soon after, with the Royal Opera Arcade (1815–1817) as the first purpose-built example, followed by the Burlington Arcade in London (1819), a 1,000-foot-long passageway enforced as pedestrian-only by beadles to maintain order and exclusivity.[28] These structures spread across Europe and to North America, such as the Cleveland Arcade (1890), influencing modern malls by prioritizing controlled, vehicle-free environments that enhanced commerce and pedestrian comfort.[29] Arcades thus prefigured 20th-century pedestrian zones by institutionalizing separation of retail from street traffic, driven by speculative investment and bourgeois leisure demands rather than traffic safety concerns.[30]Mid-20th Century Origins

The mid-20th century origins of modern pedestrian zones emerged in post-World War II Europe, driven by urban reconstruction efforts and growing concerns over automobile dominance in city centers. Devastated by wartime bombing, many European cities prioritized pedestrian-friendly designs to revitalize commercial districts while accommodating rising vehicle traffic. Rotterdam's Lijnbaan, developed after the 1940 Blitz destroyed its pre-war shopping area, exemplified this shift.[31][32] Opened on October 24, 1953, the Lijnbaan became Europe's first purpose-built pedestrian shopping precinct, spanning approximately 460 meters with low-rise buildings featuring colorful facades, overhanging roofs for shelter, and adjacent service lanes for deliveries and parking to minimize vehicular intrusion into the walking area. Architects J.H. van den Broek and J.B. Bakema designed it under the "friendship principle," emphasizing human-scale spaces with integrated greenery, benches, and public art to foster social interaction amid the era's modernist urban planning. This car-free zone contrasted sharply with prevailing car-oriented developments, addressing pedestrian safety and accessibility in dense urban settings.[31][33] The Lijnbaan's success, attracting over 100 shops and boosting local commerce, inspired subsequent pedestrian initiatives across Europe, including promenades in Warsaw, Prague, and Hamburg by the late 1950s, as well as the UK's Stevenage town center. It reflected broader mid-century trends in traffic separation, influenced by engineers like Sweden's Carl Benzén, who advocated for pedestrian precincts to reduce accidents amid surging car ownership—from 1.5 million vehicles in the UK in 1938 to over 5 million by 1960. While isolated pedestrian restrictions existed earlier, such as in 1930s Germany, the Lijnbaan pioneered comprehensive, integrated zoning that prioritized empirical urban functionality over vehicular throughput.[31][34]Late 20th to Early 21st Century Expansion

During the 1970s and 1980s, European cities pursued extensive pedestrianization as part of broader urban revitalization efforts amid rising car ownership and congestion. In Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, major centers such as Vienna, Munich, and Zurich established initial pedestrian zones in the 1970s, followed by substantial enlargements that integrated larger networks prioritizing walking and public transit over vehicles; by the 1990s, these expansions correlated with modal shifts, including a decline in car commuting from 5.5% growth in the 1970s to 1.4% in the 1990s.[35] Leading German cities like Aachen and Bonn developed interconnected pedestrian precincts totaling 4 to 9 kilometers by the decade's end, often converting high-traffic commercial streets to enhance retail viability and reduce emissions.[36] In Scandinavia, Copenhagen incrementally expanded its pedestrian areas from 1962 onward, adding significant segments in 1968, 1973, 1988, 1992, and culminating in 100,000 square meters of car-free space by 2000, which supported a pedestrian mode share exceeding 40% in the city center.[37] Similar trends emerged across Britain, where pedestrian precincts proliferated rapidly post-1960s, with most towns implementing shopping-oriented zones by 1980 to counter suburban retail flight; these initiatives, numbering over 1,000 nationwide, emphasized hardscaping and seating to boost foot traffic in declining high streets.[38] Empirical assessments from the period indicated these zones often increased pedestrian volumes by 20-50% in converted areas, though long-term retail impacts varied due to competition from out-of-town malls.[39] Contrastingly, in the United States, late-20th-century expansions peaked earlier in the 1970s with over 200 new downtown pedestrian malls created since the 1960s, aiming to revive post-industrial cores like those in Syracuse (1981) and Kalamazoo (1959, expanded 1970s); however, by the mid-1990s, economic underperformance led over 100 cities to partially reopen streets to traffic, reflecting challenges in sustaining viability without sufficient density or transit integration.[40] Into the early 2000s, global adoption accelerated selectively, with European models influencing Latin American cases like Mexico City's Centro Histórico, where 3 kilometers of streets pedestrianized in 2008 yielded a 30% rise in commercial activity alongside sharp drops in crime.[41] In Asia, efforts remained sporadic and often temporary, as high-density contexts like Hong Kong prioritized vehicular flow, limiting permanent expansions despite pilot closures in the 1980s-2000s that failed to scale due to enforcement issues and business resistance.[42] Overall, this era's growth totaled thousands of kilometers worldwide, concentrated in Europe, driven by evidence of safety gains—such as 90% reductions in accidents in converted zones—but tempered by site-specific failures where pedestrianization overlooked local economic dependencies on cars.[37][40]Post-COVID and Recent Trends

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted rapid experimentation with pedestrian zones globally, as cities closed streets to vehicles starting in early 2020 to enable social distancing, outdoor exercise, and support for struggling retail sectors through expanded al fresco dining and foot traffic areas. In the United States, at least 97 municipalities implemented temporary commercial pedestrian streets during this period, often justified by public health needs and observed increases in pedestrian activity where vehicular access was restricted.[43] These measures drew on tactical urbanism principles, allowing quick assessments of public space reconfiguration without long-term commitments.[44] Post-restrictions, a subset of these initiatives transitioned to permanence or expansion, reflecting trends toward enhanced urban resilience and walkability. New York City's Open Streets program, launched in 2020, scaled up significantly by 2025, with official evaluations documenting shifts in program size, geographic reach, and management practices over five years.[45] At least nine U.S. cities retained robust shared streets frameworks, incorporating pedestrian and cyclist enhancements based on traffic data showing sustained usage.[46] In Europe, Paris integrated pandemic-era closures into broader pedestrianization strategies, emphasizing adaptability in urban design as evidenced in literature reviews of post-2020 interventions.[47] Globally, a geospatial database of pandemic-induced street experiments highlights over 1,000 such sites, with analytical trends indicating selective permanence where empirical data supported safety and mobility gains.[48] However, economic outcomes have proven mixed, tempering enthusiasm for widespread adoption. Surveys and interviews across U.S. cities found negligible average effects on business revenues from pedestrian street conversions, though some restaurants reported gains from heightened foot traffic; pseudo-control analyses confirmed uncertainty in net benefits.[49][50] Recent developments from 2023 onward include localized backlashes and partial reversals, particularly in the UK where low-traffic neighborhoods—often overlapping with pedestrian priorities—faced resident opposition over diverted congestion, leading to dismantlement in several areas by 2024.[51] Despite this, overarching trends favor integration into planning for active travel and public health, with U.S. pedestrian fatalities declining 4.3% in 2024 amid sustained infrastructure investments, though still elevated above pre-pandemic baselines.[52]Design and Implementation

Urban Planning and Infrastructure

Urban planning for pedestrian zones emphasizes prioritizing foot traffic over vehicles, integrating zones into existing city grids through connectivity to surrounding streets and public transit hubs. Designs typically feature wide pathways, often 12 to 18 meters across, to accommodate high volumes of pedestrians without congestion, as exemplified by Rotterdam's Lijnbaan, which widened former 9-meter traffic streets into car-free promenades post-World War II reconstruction.[32] Infrastructure boundaries employ physical barriers like bollards, raised curbs, or planters to prevent unauthorized vehicle entry while allowing controlled access for deliveries and emergencies, ensuring seamless separation from motor traffic.[53] Core infrastructure elements include durable surfacing materials such as concrete pavers or granite setts, selected for their resistance to wear from constant footfall and weather exposure, often incorporating permeable options to manage stormwater runoff and reduce urban heat islands. Lighting fixtures, commonly LED-based for energy efficiency, are positioned at 3-5 meter heights along paths to enhance visibility and safety during evening hours, with designs minimizing light pollution and glare.[54] Public amenities like benches, shade trees, and waste receptacles are strategically placed to promote prolonged stays and comfort, adhering to guidelines that allocate space for frontage zones (for utilities and landscaping) and clear through-zones for unobstructed movement, typically maintaining 6-20 foot sidewalk widths in adjacent areas.[55] Integration with broader infrastructure involves linking zones to mass transit systems, such as bus stops or metro entrances within 200-400 meters, and providing peripheral parking facilities to mitigate displacement of vehicles, as seen in early implementations where zones were buffered by multi-level garages. Maintenance protocols focus on regular cleaning and repairs to sustain usability, with empirical planning drawing from standards like those in AASHTO's pedestrian facilities guide, which stress safety, comfort, and demand-responsive scaling based on projected daily pedestrian volumes exceeding 10,000 in commercial cores.[56] These elements collectively support causal linkages between design quality and usage rates, evidenced by sustained vitality in zones like Lijnbaan since its 1953 opening.[31]Policy Frameworks and Enforcement

Policy frameworks for pedestrian zones are typically established at the municipal or local government level through zoning ordinances, traffic regulation acts, and urban planning designations that prohibit or restrict vehicular access to designated areas. In the United States, cities enact specific ordinances to create pedestrian malls or zones, such as Jersey City's 2020 ordinance for the Exchange Place Pedestrian Mall, which authorizes closures for enhanced pedestrian movement and safety while allowing limited uses under municipal oversight.[57] Similarly, overlay zones target pedestrian mobility by integrating mixed-use development with vehicle restrictions, as seen in various U.S. localities adapting zoning to prioritize walking over driving.[58] In Europe, frameworks vary by nation but often stem from national traffic codes enabling local prohibitions; for instance, Germany's road traffic regulations (StVO) support Fußgängerzonen in most towns over 50,000 residents, with Berlin enacting a dedicated Pedestrian Law in 2021 to mandate walkability improvements and zone designations.[59][60] The United Kingdom relies on the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, empowering local authorities to designate pedestrian priority zones via traffic orders, though full car-free status requires explicit legal prohibition of vehicles.[61] Enforcement relies on a combination of physical infrastructure, signage, and regulatory measures to deter unauthorized vehicles while accommodating essential access like deliveries. Fixed barriers such as bollards and railings physically block entry points, often supplemented by retractable systems for timed service vehicle permits, as implemented in many European and U.S. cities to balance commerce with pedestrian priority.[62] Clear signage, including mandatory symbols under national standards (e.g., G7 in the Netherlands for pedestrian zones), warns drivers of prohibitions, with violations typically incurring fines enforced by local police or traffic wardens. In the European Union, Urban Vehicle Access Regulations (UVARs) facilitate enforcement of pedestrian areas through emission-based or time-restricted controls, with cities like Milan using automated camera systems in limited traffic zones to issue fines for non-compliance, achieving high detection rates without constant patrols.[63][64] U.S. enforcement often involves high-visibility policing under local codes, targeting right-of-way violations in zones, though effectiveness depends on consistent application to prevent circumvention during off-peak hours.[65] Liability for zone maintenance falls on municipalities, requiring regular inspections to ensure barriers and markings remain effective against incursions.[66]Accessibility and Adaptations

Pedestrian zones incorporate adaptations such as minimum pathway widths of 36 inches (91 cm) to accommodate wheelchairs and mobility aids, with allowances for brief reductions to 32 inches (81 cm) at transitions like doorways or narrow points, ensuring continuous clear routes free from protrusions exceeding 4 inches (10 cm).[67] Smooth, firm surfaces like concrete or asphalt are prioritized over uneven materials such as cobblestones to minimize vibration and fatigue for users with mobility impairments, while detectable warnings—tactile strips of truncated domes—are installed at transitions to street crossings or hazards for visually impaired pedestrians.[68] These features align with Public Right-of-Way Accessibility Guidelines (PROWAG), which mandate curb ramps with 1:12 slopes or shallower at any grade changes and pedestrian signals with accessible pedestrian pushbuttons featuring tactile arrows and audible cues.[69] For visual impairments, designs include high-contrast edging along pathways and bio-acoustic orientation aids, such as embedded wayfinding lines or apps integrated with beacons, though empirical assessments note that crowd density in zones can reduce effectiveness by obscuring cues.[70] Mobility adaptations extend to refuge islands in wider zones, requiring at least 6 feet (1.8 m) length for safe waiting, and sufficient clear space for turning wheelchairs (minimum 60-inch diameter circles).[71] Integration with public transport involves designated accessible drop-off zones at zone edges, compliant with ADA standards for level boarding, and nearby reserved parking for disabled vehicles, as seen in guidelines from cities like New York, where pedestrian mobility plans emphasize equitable sidewalk buffers and tree grate avoidance.[72] Studies on car-free areas indicate that well-adapted designs enhance overall accessibility rather than hinder it; for instance, increased walkability in such zones correlates with 33% higher transit usage among disabled individuals due to improved proximal access to stops.[73] However, challenges persist in historic pedestrian zones with inherent barriers like steps or narrow alleys, where retrofits such as elevators or platform lifts add costs but are required under standards like the ADA Title II for public entities.[74] Enforcement of maintenance—regular clearing of obstacles and snow removal—is critical, as non-compliance can negate benefits, with federal guidelines stressing detectable path continuity to prevent isolation of users with disabilities.[75]Empirical Evidence of Impacts

Safety and Accident Reduction Data

Pedestrian zones exclude motor vehicles, thereby eliminating vehicle-pedestrian collisions within the designated area as a direct result of the policy enforcement prohibiting vehicular access. This design principle ensures that the primary risks to pedestrians shift from high-impact vehicle strikes to lower-severity incidents such as collisions with bicycles, scooters, or other pedestrians, with empirical observations confirming near-zero rates of motor vehicle-related injuries inside fully implemented zones.[76][77] Studies evaluating adjacent roadways following pedestrianization find minimal displacement of traffic leading to increased accident rates elsewhere. For example, temporary road closures for pedestrian use in central Tokyo resulted in only modest 5% increases in traffic volume on nearby links, with no evidence of heightened congestion or crash risk, as the existing network absorbed changes without compromising safety.[78] Broader traffic calming measures often integrated with pedestrian zones, such as narrowed lanes and speed restrictions at boundaries, have demonstrated a 39% overall reduction in crashes, a 76% decrease in injury-producing incidents, and a 90% drop in fatal or severe injuries in evaluated urban settings.[77]| Measure | Crash Reduction | Injury Crash Reduction | Severe/Fatal Crash Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic Calming with Pedestrian Priority Elements | 39% | 76% | 90% |

.JPG/250px-Wien_-_Graben_(2).JPG)

.JPG/2000px-Wien_-_Graben_(2).JPG)