Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Automobile handling

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Automobile handling and vehicle handling are descriptions of the way a wheeled vehicle responds and reacts to the inputs of a driver, as well as how it moves along a track or road. It is commonly judged by how a vehicle performs particularly during cornering, acceleration, and braking as well as on the vehicle's directional stability when moving in steady state condition.

In the automotive industry, handling and braking are the major components of a vehicle's "active" safety. They also affect its ability to perform in auto racing. The maximum lateral acceleration is, along with braking, regarded as a vehicle’s road holding ability. Automobiles driven on public roads whose engineering requirements emphasize handling over comfort and passenger space are called sports cars.

Design factors that affect automobile handling

[edit]Weight distribution

[edit]Centre of mass height

[edit]The centre of mass height, also known as the centre of gravity height, or CGZ, relative to the track, determines load transfer (related to, but not exactly weight transfer) from side to side and causes body lean. When tires of a vehicle provide a centripetal force to pull it around a turn, the momentum of the vehicle actuates load transfer in a direction going from the vehicle's current position to a point on a path tangent to the vehicle's path. This load transfer presents itself in the form of body lean. In extreme circumstances, the vehicle may roll over.

Height of the centre of mass relative to the wheelbase determines load transfer between front and rear. The car's momentum acts at its centre of mass to tilt the car forward or backward, respectively during braking and acceleration. Since it is only the downward force that changes and not the location of the centre of mass, the effect on over/under steer is opposite to that of an actual change in the centre of mass. When a car is braking, the downward load on the front tires increases and that on the rear decreases, with corresponding change in their ability to take sideways load.

A lower centre of mass is a principal performance advantage of sports cars, compared to sedans and (especially) SUVs. Some cars have body panels made of lightweight materials partly for this reason.

Body lean can also be controlled by the springs, anti-roll bars or the roll center heights.

| Model | Model year |

CoG height |

|---|---|---|

| Dodge Ram B-150[1] | 1987 | 85 centimetres (33 in) |

| Chevrolet Tahoe[1] | 1998 | 72 centimetres (28 in) |

| Lotus Elise[2] | 2000 | 47 centimetres (19 in) |

| Tesla Model S[3][4] | 2014 | 46 centimetres (18 in) |

| Chevrolet Corvette (C7) Z51[5] | 2014 | 44.5 centimetres (18 in) |

| Alfa Romeo 4C[6] | 2013 | 40 centimetres (16 in) |

| Formula 1 Car | 2017 | 25 centimetres (10 in) |

Centre of mass

[edit]In steady-state cornering, front-heavy cars tend to understeer and rear-heavy cars to oversteer (Understeer & Oversteer explained), all other things being equal. The mid-engine design seeks to achieve the ideal center of mass, though front-engine design has the advantage of permitting a more practical engine-passenger-baggage layout. All other parameters being equal, at the hands of an expert driver a neutrally balanced mid-engine car can corner faster, but a FR (front-engined, rear-wheel drive) layout car is easier to drive at the limit.

The rearward weight bias preferred by sports and racing cars results from handling effects during the transition from straight-ahead to cornering. During corner entry the front tires, in addition to generating part of the lateral force required to accelerate the car's centre of mass into the turn, also generate a torque about the car's vertical axis that starts the car rotating into the turn. However, the lateral force being generated by the rear tires is acting in the opposite torsional sense, trying to rotate the car out of the turn. For this reason, a car with "50/50" weight distribution will understeer on initial corner entry. To avoid this problem, sports and racing cars often have a more rearward weight distribution. In the case of pure racing cars, this is typically between "40/60" and "35/65".[citation needed] This gives the front tires an advantage in overcoming the car's moment of inertia (yaw angular inertia), thus reducing corner-entry understeer.

Using wheels and tires of different sizes (proportional to the weight carried by each end) is a lever automakers can use to fine tune the resulting over/understeer characteristics.

Roll angular inertia

[edit]This increases the time it takes to settle down and follow the steering. It depends on the (square of the) height and width, and (for a uniform mass distribution) can be approximately calculated by the equation: .[7]

Greater width, then, though it counteracts center of gravity height, hurts handling by increasing angular inertia. Some high performance cars have light materials in their fenders and roofs partly for this reason

Yaw and pitch angular inertia (polar moment)

[edit]Unless the vehicle is very short, compared to its height or width, these are about equal. Angular inertia determines the rotational inertia of an object for a given rate of rotation. The yaw angular inertia tends to keep the direction the car is pointing changing at a constant rate. This makes it slower to swerve or go into a tight curve, and it also makes it slower to turn straight again. The pitch angular inertia detracts from the ability of the suspension to keep front and back tire loadings constant on uneven surfaces and therefore contributes to bump steer. Angular inertia is an integral over the square of the distance from the center of gravity, so it favors small cars even though the lever arms (wheelbase and track) also increase with scale. (Since cars have reasonable symmetrical shapes, the off-diagonal terms of the angular inertia tensor can usually be ignored.) Mass near the ends of a car can be avoided, without re-designing it to be shorter, by the use of light materials for bumpers and fenders or by deleting them entirely. If most of the weight is in the middle of the car then the vehicle will be easier to spin, and therefore will react quicker to a turn.

Suspension

[edit]Automobile suspensions have many variable characteristics, which are generally different in the front and rear and all of which affect handling. Some of these are: spring rate, damping, straight ahead camber angle, camber change with wheel travel, roll center height and the flexibility and vibration modes of the suspension elements. Suspension also affects unsprung weight.

Many cars have suspension that connects the wheels on the two sides, either by a sway bar and/or by a solid axle. The Citroën 2CV has interaction between the front and rear suspension.

Spring rate

[edit]The flexing of the frame interacts with the suspension. The following types of springs are commonly used for automobile suspension, variable rate springs and linear rate springs. When a load is applied to a linear rate spring the spring compresses an amount directly proportional to the load applied. This type of spring is commonly used in road racing applications when ride quality is not a concern. A linear spring will behave the same at all times. This provides predictable handling characteristics during high speed cornering, acceleration and braking. Variable springs have low initial springs rates. The spring rate gradually increases as it is compressed. In simple terms the spring becomes stiffer as it is compressed. The ends of the spring are wound tighter to produce a lower spring rate. When driving this cushions small road imperfections improving ride quality. However once the spring is compressed to a certain point the spring is not wound as tight providing a higher (stiffer) spring rate. This prevents excessive suspension compression and prevents dangerous body roll, which could lead to a roll over. Variable rate springs are used in cars designed for comfort as well as off-road racing vehicles. In off-road racing they allow a vehicle to absorb the violent shock from a jump effectively as well as absorb small bumps along the off-road terrain effectively.[8]

Suspension travel

[edit]The severe handling vice of the TR3B and related cars[citation needed] was caused by running out of suspension travel. Other vehicles will run out of suspension travel with some combination of bumps and turns, with similarly catastrophic effect. Excessively modified cars also may encounter this problem.

Tires and wheels

[edit]In general, softer rubber, higher hysteresis rubber and stiffer cord configurations increase road holding and improve handling. On most types of poor surfaces, large diameter wheels perform better than lower wider wheels. The depth of tread remaining greatly affects aquaplaning (riding over deep water without reaching the road surface). Increasing tire pressures reduces their slip angle, but lessening the contact area is detrimental in usual surface conditions and should be used with caution.

The amount a tire meets the road is an equation between the weight of the car and the type (and size) of its tire. A 1000 kg car can depress a 185/65/15 tire more than a 215/45/15 tire longitudinally thus having better linear grip and better braking distance not to mention better aquaplaning performance, while the wider tires have better (dry) cornering resistance.

The contemporary chemical make-up of tires is dependent of the ambient and road temperatures. Ideally a tire should be soft enough to conform to the road surface (thus having good grip), but be hard enough to last for enough duration (distance) to be economically feasible. It is usually a good idea having different set of summer and winter tires for climates having these temperatures.

Track and wheelbase

[edit]The axle track provides the resistance to lateral weight transfer and body lean. The wheelbase provides resistance to longitudinal weight transfer and to pitch angular inertia, and provides the torque lever arm to rotate the car when swerving. The wheelbase, however, is less important than angular inertia (polar moment) to the vehicle's ability to swerve quickly.

The wheelbase contributes to the vehicle's turning radius, which is also a handling characteristic.

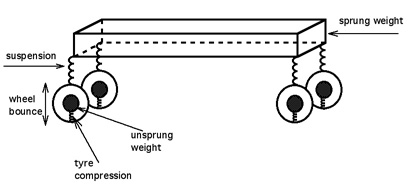

Unsprung weight

[edit]

Ignoring the flexing of other components, a car can be modeled as the sprung weight, carried by the springs, carried by the unsprung weight, carried by the tires, carried by the road. Unsprung weight is more properly regarded as a mass which has its own inherent inertia separate from the rest of the vehicle. When a wheel is pushed upwards by a bump in the road, the inertia of the wheel will cause it to be carried further upward above the height of the bump. If the force of the push is sufficiently large, the inertia of the wheel will cause the tire to completely lift off the road surface resulting in a loss of traction and control. Similarly when crossing into a sudden ground depression, the inertia of the wheel slows the rate at which it descends. If the wheel inertia is large enough, the wheel may be temporarily separated from the road surface before it has descended back into contact with the road surface.

This unsprung weight is cushioned from uneven road surfaces only by the compressive resilience of the tire (and wire wheels if fitted), which aids the wheel in remaining in contact with the road surface when the wheel inertia prevents close-following of the ground surface. However, the compressive resilience of the tire results in rolling resistance which requires additional kinetic energy to overcome, and the rolling resistance is expended in the tire as heat due to the flexing of the rubber and steel bands in the sidewalls of the tires. To reduce rolling resistance for improved fuel economy and to avoid overheating and failure of tires at high speed, tires are designed to have limited internal damping.

So the "wheel bounce" due to wheel inertia, or resonant motion of the unsprung weight moving up and down on the springiness of the tire, is only poorly damped, mainly by the dampers or shock absorbers of the suspension. For these reasons, high unsprung weight reduces road holding and increases unpredictable changes in direction on rough surfaces (as well as degrading ride comfort and increasing mechanical loads).

This unsprung weight includes the wheels and tires, usually the brakes, plus some percentage of the suspension, depending on how much of the suspension moves with the body and how much with the wheels; for instance a solid axle suspension is completely unsprung. The main factors that improve unsprung weight are a sprung differential (as opposed to live axle) and inboard brakes. (The De Dion tube suspension operates much as a live axle does, but represents an improvement because the differential is mounted to the body, thereby reducing the unsprung weight.) Wheel materials and sizes will also have an effect. Aluminium alloy wheels are common due to their weight characteristics which help to reduce unsprung mass. Magnesium alloy wheels are even lighter but corrode easily.

Since only the brakes on the driving wheels can easily be inboard, the Citroën 2CV had inertial dampers on its rear wheel hubs to damp only wheel bounce.

Aerodynamics

[edit]Aerodynamic forces are generally proportional to the square of the air speed, therefore car aerodynamics become rapidly more important as speed increases. Like darts, airplanes, racing cars etc., cars can be stabilised by fins and other rear aerodynamic devices. However, in addition to this cars also use downforce or "negative lift" to improve road holding. This is prominent on many types of racing cars, but is also used on most passenger cars to some degree, if only to counteract the tendency for the car to otherwise produce positive lift.

In addition to providing increased adhesion, car aerodynamics are frequently designed to compensate for the inherent increase in oversteer as cornering speed increases. When a car corners, it must rotate about its vertical axis as well as translate its center of mass in an arc. However, in a tight-radius (lower speed) corner the angular velocity of the car is high, while in a longer-radius (higher speed) corner the angular velocity is much lower. Therefore, the front tires have a more difficult time overcoming the car's moment of inertia during corner entry at low speed, and much less difficulty as the cornering speed increases. So the natural tendency of any car is to understeer on entry to low-speed corners and oversteer on entry to high-speed corners. To compensate for this unavoidable effect, car designers often bias the car's handling toward less corner-entry understeer (such as by lowering the front roll center), and add rearward bias to the aerodynamic downforce to compensate in higher-speed corners. The rearward aerodynamic bias may be achieved by an airfoil or "spoiler" mounted near the rear of the car, but a useful effect can also be achieved by careful shaping of the body as a whole, particularly the aft areas.

In recent years, aerodynamics have become an area of increasing focus by racing teams as well as car manufacturers. Advanced tools such as wind tunnels and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) have allowed engineers to optimize the handling characteristics of vehicles. Advanced wind tunnels such as Wind Shear's Full Scale, Rolling Road, Automotive Wind Tunnel recently built in Concord, North Carolina have taken the simulation of on-road conditions to the ultimate level of accuracy and repeatability under very controlled conditions. CFD has similarly been used as a tool to simulate aerodynamic conditions but through the use of extremely advanced computers and software to duplicate the car's design digitally then "test" that design on the computer.

Delivery of power to the wheels and brakes

[edit]The coefficient of friction of rubber on the road limits the magnitude of the vector sum of the transverse and longitudinal force. So the driven wheels or those supplying the most braking tend to slip sideways. This phenomenon is often explained by use of the circle of forces model.

One reason that sports cars are usually rear wheel drive is that power induced oversteer is useful to a skilled driver for tight curves. The weight transfer under acceleration has the opposite effect and either may dominate, depending on the conditions. Inducing oversteer by applying power in a front wheel drive car is possible via proper use of "left-foot braking", and using low gears down steep hills may cause some oversteer.

The effect of braking on handling is complicated by load transfer, which is proportional to the (negative) acceleration times the ratio of the center of gravity height to the wheelbase. The difficulty is that the acceleration at the limit of adhesion depends on the road surface, so with the same ratio of front to back braking force, a car will understeer under braking on slick surfaces and oversteer under hard braking on solid surfaces. Most modern cars combat this by varying the distribution of braking in some way. This is important with a high center of gravity, but it is also done on low center of gravity cars, from which a higher level of performance is expected.

Steering

[edit]Depending on the driver, steering force and transmission of road forces back to the steering wheel and the steering ratio of turns of the steering wheel to turns of the road wheels affect control and awareness. Play—free rotation of the steering wheel before the wheels rotate—is a common problem, especially in older model and worn cars. Another is friction. Rack and pinion steering is generally considered the best type of mechanism for control effectiveness. The linkage also contributes play and friction. Caster—offset of the steering axis from the contact patch—provides some of the self-centering tendency.

Precision of the steering is particularly important on ice or hard packed snow where the slip angle at the limit of adhesion is smaller than on dry roads.

The steering effort depends on the downward force on the steering tires and on the radius of the contact patch. So for constant tire pressure, it goes like the 1.5 power of the vehicle's weight. The driver's ability to exert torque on the wheel scales similarly with his size. The wheels must be rotated farther on a longer car to turn with a given radius. Power steering reduces the required force at the expense of feel. It is useful, mostly in parking, when the weight of a front-heavy vehicle exceeds about ten or fifteen times the driver's weight, for physically impaired drivers and when there is much friction in the steering mechanism.

Four-wheel steering has begun to be used on road cars (Some WW II reconnaissance vehicles had it). It relieves the effect of angular inertia by starting the whole car moving before it rotates toward the desired direction. It can also be used, in the other direction, to reduce the turning radius. Some cars will do one or the other, depending on the speed.

Steering geometry changes due to bumps in the road may cause the front wheels to steer in different directions together or independent of each other. The steering linkage should be designed to minimize this effect.

Electronic stability control

[edit]Electronic stability control (ESC) is a computerized technology that improves the safety of a vehicle's stability by attempting to detect and prevent skids. When ESC detects loss of steering control, the system applies individual brakes to help "steer" the vehicle where the driver wants to go. Braking is automatically applied to individual wheels, such as the outer front wheel to counter oversteer, or the inner rear wheel to counter understeer.

The stability control of some cars may not be compatible with some driving techniques, such as power induced over-steer. It is therefore, at least from a sporting point of view, preferable that it can be disabled.

Static alignment of the wheels

[edit]Of course things should be the same, left and right, for road cars. Camber affects steering because a tire generates a force towards the side that the top is leaning towards. This is called camber thrust. Additional front negative camber is used to improve the cornering ability of cars with insufficient camber gain.

Rigidity of the frame

[edit]The frame may flex with load, especially twisting on bumps. Rigidity is considered to help handling. At least it simplifies the suspension engineers work. Some cars, such as the Mercedes-Benz 300SL have had high door sills to allow a stiffer frame.

Driver handling the car

[edit]Handling is a property of the car, but different characteristics will work well with different drivers.

Familiarity

[edit]The more experience a person has with a car or type of car the more likely they will be to take full advantage of its handling characteristics under adverse conditions.[9]

Position and support for the driver

[edit]- Having to withstand g forces in his/her arms interferes with a driver's precise steering. In a similar manner, a lack of support for the seating position of the driver may cause them to move around as the car undergoes rapid acceleration (through cornering, taking off or braking). This interferes with precise control inputs, making the car more difficult to control.

- Being able to reach the controls easily is also an important consideration,[9] especially if a car is being driven hard.

- In some circumstances, good support may allow a driver to retain some control, even after a minor accident or after the first stage of an accident.

External conditions that affect handling

[edit]Weather

[edit]Weather affects handling by changing the amount of available traction on a surface. Different tires do best in different weather. Deep water is an exception to the rule that wider tires improve road holding.

Road condition

[edit]Cars with relatively soft suspension and with low unsprung weight are least affected by uneven surfaces, while on flat smooth surfaces the stiffer the better. Unexpected water, ice, oil, etc. are hazards.

Common handling problems

[edit]When any wheel leaves contact with the road there is a change in handling, so the suspension should keep all four (or three) wheels on the road in spite of hard cornering, swerving and bumps in the road. It is very important for handling, as well as other reasons, not to run out of suspension travel and "bottom" or "top".

It is usually most desirable to have the car adjusted for a small amount of understeer, so that it responds predictably to a turn of the steering wheel and the rear wheels have a smaller slip angle than the front wheels. However this may not be achievable for all loading, road and weather conditions, speed ranges, or while turning under acceleration or braking. Ideally, a car should carry passengers and baggage near its center of gravity and have similar tire loading, camber angle and roll stiffness in front and back to minimise the variation in handling characteristics. A driver can learn to deal with excessive oversteer or understeer, but not if it varies greatly in a short period of time.

The most important common handling failings are;

- Understeer – the front wheels tend to crawl slightly or even slip and drift towards the outside of the turn. The driver can compensate by turning a little more tightly, but road-holding is reduced, the car's behaviour is less predictable and the tires are liable to wear more quickly.

- Oversteer – the rear wheels tend to crawl or slip towards the outside of the turn more than the front. The driver must correct by steering away from the corner, otherwise the car is liable to spin, if pushed to its limit. Oversteer is sometimes useful, to assist in steering, especially if it occurs only when the driver chooses it by applying power.

- Bump steer – the effect of irregularity of a road surface on the angle or motion of a car. It may be the result of the kinematic motion of the suspension rising or falling, causing toe-in or toe-out at the loaded wheel, ultimately affecting the yaw angle (heading) of the car. It may also be caused by defective or worn out suspension components. This will always happen under some conditions but depends on suspension, steering linkage, unsprung weight, angular inertia, differential type, frame rigidity, tires and tire pressures. If suspension travel is exhausted the wheel either bottoms or loses contact with the road. As with hard turning on flat roads, it is better if the wheel picks up by the spring reaching its neutral shape, rather than by suddenly contacting a limiting structure of the suspension.

- Body roll – the car leans towards the outside of the curve. This interferes with the driver's control, because they must wait for the car to finish leaning before they can fully judge the effect of his steering change. It also adds to the delay before the car moves in the desired direction. It also slightly changes the weight borne by the tires as described in weight transfer.

- Excessive load transfer – On any vehicle that is cornering, the outside wheels are more heavily loaded than the inside due to the CG being above the ground. Total weight transfer (sum of front and back), in steady cornering, is determined by the ratio of the height of a car's center of gravity to its axle track. When the weight transfer equals half the vehicle's loaded weight, it will start to roll over. This can be avoided by manually or automatically reducing the turn rate, but this causes further reduction in road-holding.

- Slow response – sideways acceleration does not start immediately when the steering is turned and may not stop immediately when it is returned to center. This is partly caused by body roll. Other causes include tires with high slip angle, and yaw and roll angular inertia. Roll angular inertia aggravates body roll by delaying it. Soft tires aggravate yaw angular inertia by waiting for the car to reach their slip angle before turning the car.

Compromises

[edit]Ride quality and handling have always been a compromise - technology has over time allowed automakers to combine more of both features in the same vehicle. High levels of comfort are difficult to reconcile with a low center of gravity, body roll resistance, low angular inertia, support for the driver, steering feel and other characteristics that make a car handle well.

For ordinary production cars, manufactures err towards deliberate understeer as this is safer for inexperienced or inattentive drivers than is oversteer. Other compromises involve comfort and utility, such as preference for a softer smoother ride or more seating capacity.

Inboard brakes improve both handling and comfort but take up space and are harder to cool. Large engines tend to make cars front or rear heavy. Fuel economy, staying cool at high speeds, ride comfort and long wear all tend to conflict with road holding, while wet, dry, deep water and snow road holding are not exactly compatible. A-arm or wishbone front suspension tends to give better handling, because it provides the engineers more freedom to choose the geometry, and more road holding, because the camber is better suited to radial tires, than MacPherson strut, but it takes more space.

The older Live axle rear suspension technology, familiar from the Ford Model T, is still widely used in most sport utility vehicles and trucks, often for the purposes of durability (and cost). The live axle suspension is still used in some sports cars, like the Ford Mustang (model years before 2015), and is better for drag racing, but generally has problems with grip on bumpy corners, fast corners[citation needed] and stability at high speeds on bumpy straights.

Aftermarket modifications and adjustments

[edit]Lowering the center of gravity will always help the handling (as well as reduce the chance of roll-over). This can be done to some extent by using plastic windows (or none) and light roof, hood (bonnet) and trunk (boot) lid materials, by reducing the ground clearance, etc. Increasing the track with "reversed" wheels will have a similar effect, but the wider the car the less spare room it has on the road and the farther it may have to swerve to miss an obstacle.

Stiffer springs and/or shocks, both front and rear, will generally improve handling on close to perfect surfaces, while worsening handling on less-than-perfect road conditions by "skipping" the car (and destroying grip), thus making handling the vehicle difficult. Aftermarket performance suspension kits are usually readily available.

Lighter (mostly aluminum or magnesium alloy) wheels improve handling as well as ride comfort, by lessening unsprung weight.

Moment of inertia can be reduced by using lighter bumpers and wings (fenders), or none at all.

Fixing understeer or oversteer conditions is achieved by either an increase or decrease in grip on the front or rear axles. If the front axle has more grip than a similar vehicle with neutral steer characteristics, the vehicle will oversteer. The oversteering vehicle may be "tuned" by hopefully increasing rear axle grip, or alternatively by reducing front axle grip. The opposite is true for an understeering vehicle (rear axle has excess grip, fixed by increasing front grip or reducing rear grip). The following actions will have the tendency to "increase the grip" of an axle. Increasing moment arm distance to cg, reducing lateral load transfer (softening shocks, softening sway bars, increasing track width), increasing tire contact patch size, increasing the longitudinal load transfer to that axle, and decreasing tire pressure.

| Component | Reduce Under-steer | Reduce Over-steer |

|---|---|---|

| Weight distribution | center of gravity towards rear | center of gravity towards front |

| Front shock absorber | softer | stiffer |

| Rear shock absorber | stiffer | softer |

| Front sway bar | softer | stiffer |

| Rear sway bar | stiffer | softer |

| Front tire selection1 | larger contact area2 | smaller contact area |

| Rear tire selection | smaller contact area | larger contact area2 |

| Front wheel rim width | larger2 | smaller |

| Rear wheel rim width | smaller | larger2 |

| Front tire pressure | lower pressure | higher pressure |

| Rear tire pressure | higher pressure | lower pressure |

| Front wheel camber | increase negative camber | reduce negative camber |

| Rear wheel camber | reduce negative camber | increase negative camber |

| Rear spoiler | smaller | larger |

| Front height (because these usually affect camber and roll resistance) |

lower front end | raise front end |

| Rear height | raise rear end | lower rear end |

| Front toe in | decrease | increase |

| Rear toe in | decrease | increase |

| 1) Tire contact area can be increased by using tires with fewer grooves in the tread pattern. Of course fewer grooves has the opposite effect in wet weather or other poor road conditions.

2) Considering same tire width, and up to a point for the tire width. | ||

Cars with unusual handling problems

[edit]Certain vehicles can be involved in a disproportionate share of single-vehicle accidents; their handling characteristics may play a role:

- Early Porsche 911s – suffered from treacherous lift off oversteer (where the rear of the car loses grip as the driver lifts off the accelerator); also the inside front wheel leaves the road during hard cornering on dry pavement, causing increasing understeer. The roll bar stiffness at the front is set to compensate for the rear-heaviness and gives neutral handling in ordinary driving. This compensation starts to give out when the wheel lifts. A skilled driver can use the 911's other features to his/her advantage, making the 911 an extremely capable sports car in expert hands. Later 911s have had increasingly sophisticated rear suspensions and larger rear tires, eliminating these problems.[citation needed]

- Triumph TR2, and TR3 – began to oversteer more suddenly when their inside rear wheel lifted.[citation needed]

- Volkswagen Beetle – (original Beetle) senstitivity to crosswinds, due to the lightness of the front of the rear engine car; and poor roll stability due to the swing axle suspension. People who drove them hard fitted reversed wheels and bigger rear tires and rims to ameliorate.[citation needed]

- Chevrolet Corvair - poor roll stability due to the swing axle rear suspension similar to that used in the Volkswagen Beetle, and cited for dangerous handling in Ralph Nader's book Unsafe at Any Speed. These problems were corrected with the redesign of the Corvair for 1965, but sales did not recover from the negative publicity and it was discontinued.

- The large, rear-engine Tatra 87 (known as the 'Czech secret weapon') killed so many Nazi officers during World War II that the German Army eventually forbade its officers from driving the Tatra.[10]

- Some 1950s American "full size" cars responded very slowly to steering changes because of their very large angular inertia, softly tuned suspension which made ride quality a priority over cornering, and comfort oriented cross bias tires. Auto Motor und Sport reported on one of these that they lacked the courage to test it for top speed.[citation needed]

- Dodge Omni and Plymouth Horizon – these early American responses to the Volkswagen Rabbit were found "unacceptable" in their initial testing by Consumer Reports, due to an observed tendency to display an uncontrollable oscillating yaw from side to side under certain steering inputs. While Chrysler's denials of this behaviour were countered by a persistent trickle of independent reports of this behaviour, production of the cars was altered to equip them with both a lighter weight steering wheel and a steering damper, and no further reports of this problem were heard.[citation needed]

- The Suzuki Samurai – was similarly reported by Consumer Reports to exhibit a propensity to tipping over onto two wheels, to the point where Consumer Reports claimed they were afraid to continue testing the vehicle without the attachment of outrigger wheels to catch it from completely rolling over. In its first set of tests, the Samurai performed well.[11] R. David Little, Consumers Union's technical director, drove the light SUV through several short, hard turns, designed to simulate an emergency, such as trying to avoid a child running in front of the car. An article published several years later in a Consumer Reports anniversary issue prompted Suzuki to sue. The suit was based on the perception that Consumer Reports rigged the results: "This case is about lying and cheating by Consumers Union for its own financial motives," George F. Ball, Suzuki's managing counsel, said Monday. "They were in debt [in 1988], and they needed a blockbuster story to raise and solicit funds."[11] Entrepreneur Magazine reported that "Suzuki's case centered on a change CU made while testing the vehicle. After the Samurai and other SUVs completed the standard course without threatening to roll over, CU altered the course to make the turns more abrupt. The other vehicles didn't show a problem, but the Samurai tipped up and would have rolled over but for outriggers set up to prevent that outcome"[12] After eight years in court the parties consented to a settlement which did not include monetary damages nor a retraction.[13] Commenting on the settlement, Consumer Union said,"Consumers Union also says in the agreement that it "never intended to imply that the Samurai easily rolls over in routine driving conditions."[14] CU Vice President of Technical Policy further stated: "There is no apology. "We stand fully behind our testing and rating of the Samurai." In a joint press statement Suzuki recognized "CU's stated commitment for objective and unbiased testing and reporting."[15]

- Mercedes-Benz A-Class – a tall car with a high center of gravity; early models showed excessive body roll during sharp swerving manoeuvres and rolled over, most particularly during the Swedish moose test. This was later corrected using Electronic Stability Control and retrofitted at great expense to earlier cars.

- Ford Explorer – a dangerous tendency to blow a rear tire and flip over. Ford had constructed a vehicle with a high center of gravity; between 68 and 74 cm above ground (depending on model).[1] The tendency to roll over on sharp changes in direction is built into the vehicle. Ford attempted to counteract the forces of nature by specifying lower than optimum pressures in the tires in order to induce them to lose traction and slide under sideways forces rather than to grip and force the vehicle to roll over. For reasons that were never entirely clear, tires from one factory tended to blow out when under inflated, these vehicles then rolled over, which led to a spate of well publicized single-vehicle accidents.

- Ford and Firestone, the makers of the tires, pointed fingers at each other, with the final blame being assigned to quality control practices at a Firestone plant which was undergoing a strike. Tires from a different Firestone plant were not associated with this problem. An internal document dated 1989 states

- Engineering has recommended use of tire pressures below maximum allowable inflation levels for all UN46 tires. As described previously, the reduced tire pressures increase understeer and reduce maximum cornering capacity (both 'stabilising' influences). This practice has been used routinely in heavy duty pick-up truck and car station wagon applications to assure adequate understeer under all loading conditions. Nissan (Pathfinder), Toyota, Chevrolet, and Dodge also reduce tire pressures for selected applications. While we cannot be sure of their reasons, similarities in vehicle loading suggest that maintaining a minimal level of understeer under rear-loaded conditions may be the compelling factor.[16]

- This contributed to build-up of heat and tire deterioration under sustained high speed use, and eventual failure of the most highly stressed tire. Of course, the possibility that slightly substandard tire construction and slightly higher than average tire stress, neither of which would be problematic in themselves, would in combination result in tire failure is quite likely. The controversy continues without unequivocal conclusions, but it also brought public attention to a generally high incidence of rollover accidents involving SUVs, which the manufacturers continue to address in various ways. A subsequent NHTSA investigation of real world accident data showed that the SUVs in question were no more likely to roll over than any other SUV, after a tread separation.[17]

- The Jensen GT (hatchback coupe) – was introduced in attempt to broaden the sales base of the Jensen Healey, which had up to that time been a roadster or convertible. Its road test report in Motor Magazine and a very similar one, soon after, in Road & Track concluded that it was no longer fun enough to drive to be worth that much money. They blamed it on minor suspension changes. Much more likely, the change in weight distribution was at fault[citation needed]. The Jensen Healey was a rather low and wide fairly expensive sports car, but the specifications of its suspension were not particularly impressive, having a solid rear axle. Unlike the AC Ace, with its double transverse leaf rear suspension and aluminium body, the Jensen Healey could not stand the weight of that high up metal and glass and still earn a premium price for its handling. The changes also included a cast iron exhaust manifold replacing the aluminium one, probably to partly balance the high and far back weight of the top. The factory building was used to build multi-tub truck frames.[citation needed]

- The rear engined Renault Dauphine earned in Spain the sobriquet of the "widow's car", due to its bad handling.[citation needed]

- Three-wheeled cars/vehicles have unique handling issues, especially considering whether the single wheel is at the front or back. (Motorcycles with sidecars; another matter.) Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion car caused a sensation, but ignorance of the problems of rear-wheel-steering led to a fatal crash that destroyed its reputation.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Gary J. Heydinger et al. "Measured Vehicle Inertial Parameters - NHTSA's Data Through November 1998 Archived 2016-06-30 at the Wayback Machine" page 16+18. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1999

- ^ "Suspension". 2014-02-04. Archived from the original on 2016-06-25. Retrieved 2016-06-05.

The Lotus Elise has a kinematic roll center height of 30mm above the ground and a centre of gravity height of 470mm [18½"]. The Lotus Elise RCH is 6% the height of the CG, meaning 6% of lateral force is transferred through the suspension arms and 94% is transferred through the springs and dampers.

- ^ Roper, L. David. "Tesla Model S Data". Archived from the original on 2019-09-11. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- ^ David Biello. "How Tesla Motors Builds One of the World's Safest Cars [Video]". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2018-11-07. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ^ "2014 Chevrolet Corvette Stingray Z51". 1 November 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

Its center-of-gravity height—17.5 inches—is the lowest we've yet measured

- ^ Connor Stephenson (24 September 2013). "Alfa Romeo 4C Review". CarAdvice.com.au. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

the centre of gravity is just 40cm off the ground

- ^ Gross, Dietmar; Hauger, Werner; Schröder, Jörg; Wall, Wolfgang A.; Rajapakse, Nimal (2013). Engineering Mechanics 3. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30319-7. ISBN 978-3-642-30318-0.

- ^ John Milmont (24 January 2014). "Linear vs Progressive Rate Springs". Automotive Thinker. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ a b Michael Perel (July 1983). "Vehicle Familiarity and Safety" (PDF). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 27, 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-16.

In the wet surface maneuver, the unfamiliar group performed worse than the familiar group.

- ^ "Slavné české auto slaví osmdesátiny. Průkopnice aerodynamiky Tatra 77". iDNES.cz (in Czech). 2014-03-31. Archived from the original on 2017-11-14. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ a b David G. Savage (August 19, 2003). "Consumers Union Seeks Lawsuit Shield against Suzuki". LA Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "SUPREME COURT LETS SUZUKI SUE". The Free Library. Archived from the original on 2020-08-08. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- ^ Danny Hakim (July 9, 2004). "Suzuki Resolves Dispute with Consumer magazine". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Earle Eldridge (July 8, 2004). "Consumers Union, Suzuki settle suit". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- ^ "Suzuki And Consumers Union Agree To Settle Lawsuit". Consumersunion.org. 2004-07-08. Archived from the original on 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ "Firestone/Ford Knowledge of Tire Safety Defect". Public Citizen. Archived from the original on March 29, 2002.

- ^ "NHTSA Denies Firestone Request For Ford Explorer Investigation". NHTSA. Archived from the original on 2012-08-11. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

External links

[edit]Automobile handling

View on GrokipediaFundamentals and Physics

Core Principles of Vehicle Dynamics

Vehicle dynamics applies principles of classical mechanics to analyze and predict the motion of automobiles under driver inputs, road conditions, and external forces. A rigid-body vehicle possesses six degrees of freedom: three translational—surge (longitudinal), sway (lateral), and heave (vertical)—and three rotational—roll, pitch, and yaw.[4] Handling primarily concerns lateral and yaw dynamics, where steering generates lateral tire forces to induce turning, balanced against inertial tendencies to continue straight motion per Newton's first law.[5] Central to lateral handling is the tire's ability to generate cornering force through deformation at the contact patch. The slip angle, defined as the angle between the tire's heading direction and the actual velocity vector of the contact patch, determines lateral force in the linear regime via Fy = C_α α, where C_α is the tire's cornering stiffness (typically 50,000–200,000 N/rad for passenger car tires, varying with load and compound).[6] [7] Beyond small angles (around 5–10 degrees), the force-slip curve peaks and declines, leading to saturation and potential loss of grip.[8] The bicycle model simplifies analysis by collapsing left-right wheels into single front and rear equivalents, yielding two degrees of freedom: vehicle sideslip β (atan(v/u), with v lateral velocity, u longitudinal) and yaw rate r (dψ/dt, ψ yaw angle).[4] [9] Steering angle δ at the front produces front slip angle α_f ≈ δ - (β + (l_f / u) r), rear α_r ≈ - (β - (l_r / u) r), where l_f and l_r are distances from center of gravity to front and rear axles.[10] Resulting yaw moment M_z = l_f F_yf - l_r F_yr resists or induces rotation, with vehicle yaw inertia I_z (often approximated as m a^2 where a is track width-related gyration radius, around 2000–5000 kg·m² for sedans) governing angular acceleration per τ = I α.[4] In steady-state cornering at speed V and radius R, yaw rate r = V/R, and balance requires total lateral force m V²/R equals sum of tire Fy, with understeer occurring if front α_f > α_r (due to higher front stiffness or load sensitivity), demanding more steering lock for equilibrium; neutral steer aligns α_f = α_r, maximizing transient response.[10] [11] Weight transfer from lateral acceleration a_y = V²/R shifts normal loads outward (ΔF_z = (m h_g a_y)/(t), h_g CG height, t track width), reducing total cornering capacity by up to 20–30% at 1g due to tire load sensitivity (Fy nonlinear with F_z).[12] This couples with roll dynamics, where suspension geometry and stiffness modulate load distribution to sustain grip.[13]Key Handling Metrics and Behaviors

Understeer, oversteer, and neutral steer represent the primary steady-state handling behaviors of automobiles during cornering. Understeer occurs when the front axle's normalized cornering stiffness is lower than the rear's, resulting in the front tires reaching their slip angle limit before the rear tires; this causes the vehicle to follow a wider path than intended, necessitating increased steering input to sustain the turn radius as lateral acceleration rises.[14] Oversteer arises when the rear axle's cornering stiffness is lower, leading the rear tires to lose traction first and the vehicle to yaw excessively relative to the steering angle, which can promote instability or spins without corrective action such as throttle modulation or countersteering.[14] Neutral steer is achieved when front and rear axle cornering stiffnesses are balanced, producing equal slip angles and minimal variation in required steering angle with increasing speed or lateral demands, though perfect neutrality is rare in production vehicles due to tire nonlinearities and load transfers.[14] The understeer gradient (η or K_us), a core metric for quantifying these behaviors, is defined as the change in required steer angle per unit lateral acceleration in steady-state cornering, with η = (Y_r - N β) / (m g L), where Y_r is the lateral force sensitivity to sideslip, N is the yaw stiffness, β is sideslip angle, m is vehicle mass, g is gravitational acceleration, and L is wheelbase; alternatively, it approximates as K_us = (m_f / C_{αf} - m_r / C_{αr}), with m_f and m_r as front/rear mass fractions and C_{αf}/C_{αr} as axle cornering stiffnesses.[14] [15] Positive η (>0, typically 0.02–0.05 deg/g for passenger cars) denotes understeer, promoting stability for average drivers; negative η indicates oversteer, enhancing agility but risking directional instability beyond a critical speed u_cr where yaw response diverges; zero η yields neutral handling.[14] [16] Lateral acceleration (a_y), measured in g-forces via accelerometers during skidpad or constant-radius tests, gauges maximum sustainable cornering force before tire saturation, typically peaking at 0.8–1.2 g for high-performance sedans and up to 1.5 g or more for sports cars with wide tires and low profiles; it integrates yaw rate (r) and sideslip velocity (V_y) as a_y ≈ r V_x + dV_y/dt, where V_x is forward speed, serving as a proxy for overall grip limits and understeer progression.[17] [16] Yaw rate (r, in deg/s), captured by gyroscopes in dynamic maneuvers like ISO 3888-1 double-lane changes, evaluates rotational responsiveness, with steady-state yaw rate gain (r / δ_sw, where δ_sw is steering wheel angle) assessing linearity—values near 20–30 deg/s per radian of handwheel input indicate responsive yet stable handling, while deviations signal understeer (lower gain) or oversteer (higher initial gain dropping at higher speeds).[18] [19] Transient behaviors, such as yaw rate overshoot or phase lag in step-steer tests, complement steady-state metrics by revealing response time and damping; for instance, low overshoot (<10%) in a 100 deg/s yaw demand favors predictable control, while excessive roll angle (beyond 4–6 deg under 0.8 g) from soft suspensions reduces effective tire camber thrust and exacerbates load imbalance.[20] [21] These metrics, derived from instrumented vehicle testing per standards like SAE J266, inform design trade-offs, with front-wheel-drive cars inherently understeering due to longitudinal load shift under power (increasing front slip angles) and rear-drive setups prone to oversteer from torque-induced rear slip.[14][22]Historical Development

Early Innovations in Chassis and Suspension

The earliest automobile chassis designs drew from horse-drawn carriage frames but incorporated steel construction for enhanced rigidity, essential for transmitting steering inputs and withstanding dynamic loads during motion. Karl Benz's 1886 Patent-Motorwagen utilized a simple tubular steel chassis suspended by long leaf springs, marking an initial adaptation that provided basic structural support and shock absorption over uneven surfaces, though it resulted in a harsh ride due to minimal damping.[23] [24] This rigid frame configuration prioritized durability over flexibility, limiting handling responsiveness but enabling the vehicle's operational stability at low speeds up to 16 km/h. Suspension systems in these pioneer vehicles predominantly relied on leaf springs, evolved from full-elliptic arrangements—where springs formed complete ovals for maximum compliance—to semi-elliptic setups by the early 1900s, which offered improved load-bearing capacity and fore-aft articulation while maintaining wheel contact with the road. A pivotal advancement occurred in 1906 with the Brush Runabout, the first production car to integrate front coil springs on a flexible hickory axle alongside mechanical shock absorbers, effectively damping spring oscillations and reducing body bounce, which enhanced directional stability and tire grip during maneuvers.[25] [26] [27] Further chassis innovation emerged with the American Underslung series starting in 1907, featuring an inverted "underslung" frame positioned below the axles rather than atop them, which lowered the center of gravity by approximately 10-15 cm compared to conventional designs and markedly improved rollover resistance and cornering poise on rutted roads.[28] [29] [30] This geometry preserved ground clearance for axles while concentrating mass lower in the vehicle, yielding more predictable handling traits such as reduced body lean and quicker transient response, attributes praised in period tests for transforming high-speed stability without compromising off-road capability. These developments collectively shifted early automotive dynamics from mere survivability to rudimentary control, setting precedents for isolating chassis flex and optimizing weight distribution to mitigate understeer and oversteer tendencies inherent in solid-axle setups.Mid-20th Century Advances and Controversies

In the post-World War II era, the adoption of radial-ply tires marked a significant advance in automobile handling, as their construction—with cords running perpendicular to the direction of travel—provided greater sidewall stiffness, improved cornering stability, and a larger, more consistent contact patch compared to bias-ply tires.[31] Michelin introduced the first radial tires for passenger cars in 1948 on the Citroën 2CV, though widespread use in the United States lagged until the late 1960s, when manufacturers like General Motors began offering them as options, enhancing predictability during turns and reducing sidewall flex that could lead to unpredictable behavior.[32] Suspension innovations also progressed, with torsion bar systems gaining prominence for their compact design and tunable ride characteristics, allowing better control of wheel motion and reduced body roll in corners. Chrysler Corporation pioneered torsion bar suspension in its 1957 models, such as the Plymouth Fury, which improved handling by providing progressive damping and maintaining tire contact under load, a step beyond rigid axles common in earlier American vehicles.[33] Independent front suspension, already experimented with pre-war, became standard in many mid-1960s designs, enabling sharper steering response and less dive under braking by isolating each wheel's movement.[26] A major controversy arose with the 1960 Chevrolet Corvair, whose rear-engine layout resulted in a rear-heavy weight distribution—approximately 60% over the rear axle when unloaded—combined with a swing-axle rear suspension that promoted oversteer, where the rear wheels lost traction first in sharp maneuvers, potentially leading to spins if drivers overcorrected.[34] Consumer advocate Ralph Nader spotlighted these traits in his 1965 book Unsafe at Any Speed, arguing the design's sensitivity to tire pressure imbalances (e.g., low rear pressures exacerbating tuck-under effects) made it inherently unstable for average drivers, fueling public debate on engineering trade-offs between innovation and safety.[35] However, a 1971 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration investigation concluded that early Corvairs (1960–1963) exhibited no greater loss-of-control risk than comparable front-engine contemporaries like the Ford Falcon or Plymouth Valiant, attributing issues partly to driver unfamiliarity with rear-engine dynamics rather than unique flaws, while later models (1964 onward) incorporated a front stabilizer bar to mitigate oversteer.[36] This episode highlighted tensions between performance-oriented designs and mass-market predictability, influencing subsequent federal safety standards like requirements for handling stability testing.[36]Late 20th to Early 21st Century Refinements

The integration of electronic control systems marked a profound refinement in automobile handling during the late 20th century, building on earlier mechanical innovations to enhance stability and predictability. Anti-lock braking systems (ABS), which modulate brake pressure to prevent wheel lockup and preserve steering control during hard stops, transitioned from luxury options to widespread adoption by the 1990s following their initial production debut in the 1970s.[37] Traction control systems, introduced in the late 1980s by manufacturers like BMW and Porsche, intervened via throttle reduction or selective braking to mitigate wheel spin on low-grip surfaces, thereby improving cornering traction without compromising driver input.[38] Electronic stability control (ESC), a synthesis of ABS and traction control principles, represented the era's most transformative handling advancement. Conceived in 1989 by Mercedes-Benz engineer Frank Werner-Mohn during an icy-road incident, ESC employs yaw rate, lateral acceleration, and wheel speed sensors to detect deviations from the driver's intended trajectory, then applies targeted braking to individual wheels or adjusts engine torque to counteract understeer or oversteer.[39] Bosch commercialized the system as ESP in 1995 on the Mercedes-Benz S-Class (W140), where it reduced skidding by up to 30% in real-world tests; by 1997, variants like Cadillac's StabiliTrak and Delphi's implementations expanded its reach.[40] [41] Early 21st-century mandates, such as the U.S. NHTSA requirement for all passenger vehicles by 2012, stemmed from data showing ESC prevented approximately 750,000 accidents and saved over 22,000 lives globally by 2023.[40] Steering geometry refinements complemented these electronic aids, with four-wheel steering (4WS) systems enhancing low-speed maneuverability and high-speed stability. Honda pioneered production 4WS in the 1987 Prelude, employing a mechanical linkage that phased rear wheels in opposite directions to the fronts at speeds below 40 km/h for a tighter turning radius (reducing it by about 30%), and in the same direction above that threshold to minimize yaw disturbances during lane changes.[42] [43] Nissan and Mazda followed with similar mechanical setups in models like the 1988 300ZX and 626, achieving up to 5 degrees of rear-wheel articulation; electronic variants, using actuators for precise control, proliferated in the 1990s and 2000s, as seen in Nissan's HICAS system, which improved handling metrics like lane-change response time by 10-15% in instrumented tests.[44] [45] Suspension and chassis technologies evolved toward active intervention for superior roll control and ride-handling balance. Semi-active dampers, adjustable via solenoid valves in response to road inputs, gained traction in the 1990s, as in BMW's 1999 7 Series with Dynamic Drive, which hydraulically countered body lean by up to 50% during cornering.[46] Fully active systems, like Mercedes-Benz's 1999 Active Body Control (ABC) on the CL-Class, used hydraulic actuators to preemptively adjust wheel loads, reducing lateral acceleration felt by occupants by 40% in slalom maneuvers compared to passive setups.[47] These refinements, informed by computational vehicle dynamics simulations increasingly adopted since the 1980s, prioritized causal factors like center-of-gravity management and tire load transfer, yielding measurable gains in metrics such as skidpad grip (often exceeding 0.9g for production sedans by 2010).[47]Vehicle Design Factors

Mass Properties and Weight Distribution

Mass properties of an automobile include its total mass, the location of the center of gravity (CG), and the moments of inertia about principal axes, all of which dictate load transfer during maneuvers and thus profoundly shape handling characteristics. The CG's longitudinal position establishes static axle load distribution, typically ranging from 55-60% on the front axle for conventional front-engine sedans due to engine placement forward of the firewall, which induces a natural understeer bias by increasing front tire loading in steady-state cornering.[48] Rear-engine layouts, conversely, yield distributions like 40% front / 60% rear, promoting oversteer by shifting more static load rearward, which enhances rear tire slip angle sensitivity under power but demands precise control to mitigate snap oversteer.[49] During dynamic events, such as braking, forward weight shift—governed by the CG's horizontal distance from the rear axle—unloads the rear tires, potentially inducing oversteer if the distribution is rear-biased, while acceleration transfers load rearward, reducing front grip in front-biased setups.[50] The vertical CG height governs lateral stability and rollover resistance; a higher CG amplifies the overturning moment in cornering, as the lateral acceleration produces a destabilizing torque proportional to , where is mass, is CG height, and is gravity.[51] Lowering —achievable via engine placement between axles or suspension design—reduces roll angle for a given lateral force, allowing higher cornering speeds before tire saturation, with measurements showing typical passenger cars at 18-22 inches (457-559 mm) versus sports cars at 15-18 inches (381-457 mm).[52] Lateral CG offset, minimized in symmetric designs, prevents uneven axle loading that could exacerbate understeer or oversteer on banked surfaces.[53] Moments of inertia, particularly yaw (about the vertical axis) and roll (about the longitudinal axis), influence transient response; a lower yaw inertia—reduced by concentrating mass centrally—accelerates steering yaw rate buildup, sharpening turn-in but risking instability in high-speed steady-state turns, while higher roll inertia demands stiffer anti-roll bars to control body lean without excessive tire camber variation.[54] In quantitative terms, roll inertia correlates strongly with total mass, with a 50% increase potentially halving the dynamic rollover threshold under aggressive maneuvers, underscoring the need for low polar mass distribution in performance vehicles.[55] These properties interact causally with suspension tuning: for instance, Thomas Gillespie's analysis in Fundamentals of Vehicle Dynamics derives understeer gradient as a function of axle weights and pneumatic trail, revealing how rearward CG shifts amplify oversteer by elevating rear slip angle gradients relative to front.[56] Optimal handling thus requires balancing these inertias against tire friction limits, often verified through pendulum tests for CG and torsional pendulums for inertias.[57]Suspension Systems and Geometry

Suspension systems link the wheels to the chassis, absorbing road disturbances while controlling wheel position and orientation to maintain tire contact patch integrity during dynamic maneuvers.[58] These systems dictate vehicle roll, pitch, and camber variations, directly impacting lateral acceleration limits and stability through kinematic constraints and compliance properties.[59] Springs and dampers manage vertical compliance, but the linkage geometry governs how forces from acceleration, braking, and cornering translate into wheel alignment changes, influencing understeer, oversteer, and transient response.[60] Dampers (shock absorbers) control the rate of suspension movement and load transfer during transients. Stiffer rear shock absorbers, particularly with higher rebound damping rates, generally promote oversteer by loosening the rear end, making it more prone to sliding out during cornering transitions. This occurs because increased rebound damping resists suspension extension, accelerating load transfer and unloading the inside rear tire faster, thereby reducing rear grip relative to the front. Stiffer rear damping also improves control of body motion, reducing excessive roll and enhancing responsiveness. However, excessive stiffness may produce a harsher ride and reduce mechanical grip over bumps due to diminished compliance with road irregularities.[61][62] Dependent suspensions, featuring a solid axle connecting both wheels, enforce parallel motion, which simplifies construction and supports heavy loads but induces camber and toe alterations on uneven surfaces, reducing cornering precision as one wheel's bump affects the other.[63] Independent suspensions decouple wheel movements, permitting tailored kinematics that preserve tire perpendicularity under load, thereby enhancing grip and reducing body roll sensitivity.[64] Double wishbone designs employ upper and lower control arms to precisely control wheel path, minimizing scrub and offering adjustable camber gain for sustained lateral forces in turns, as seen in performance vehicles where this setup allows 1-2 degrees of negative camber recovery during compression.[63] [65] MacPherson struts integrate the shock as an upper locator, providing cost-effective packaging for front-wheel-drive cars but constraining camber tuning due to fixed pivot geometry, often leading to higher understeer gradients compared to multi-link variants.[66] Suspension geometry parameters—camber, caster, toe, and kingpin inclination—define static and dynamic wheel alignment, causal to handling traits via their effects on tire slip angles and self-aligning torques.[67] Camber angle, typically set statically negative by 0.5-2 degrees, counters body roll-induced positive tilt, ensuring the tire contact patch remains flat for maximal friction coefficient utilization; dynamic gain from arm lengths (e.g., longer lower arms yielding positive gain) prevents excessive outer wheel camber loss in corners, directly correlating to cornering stiffness.[66] [68] Caster, angled rearward 3-7 degrees at the steering axis, generates mechanical trail (caster angle times kingpin offset) that promotes straight-line return-to-center via lateral forces, stabilizing high-speed tracking but inducing torque steer if unbalanced front-to-rear.[67] Toe settings, with slight in-toe (0.1-0.3 degrees) promoting convergence for straight stability or out-toe for agile turn-in, alter Ackermann compliance; excessive toe variation under bump increases yaw damping but accelerates inner tire wear.[69] The roll center, the instantaneous pivot for lateral load transfer derived from front-view suspension links' intersection (or strut projection for MacPherson), positions ideally low (near ground) to minimize jacking forces and roll moment arm, though virtual roll axis migration with bump affects understeer balance—higher rear centers promote oversteer by shifting load rearward.[70] Anti-dive and anti-squat geometries counteract pitch: front anti-dive (20-50% typical) orients lower arms upward relative to the instant center under braking torque reaction, reducing nose dip by vectoring suspension forces against deceleration squat; rear anti-squat similarly uses drive-line angle to lift under acceleration, percentages computed as (instant center height / wheelbase) times trigonometric link factors, preventing traction loss from excessive roll axis drop.[71] [72] These parameters interlink—e.g., aggressive anti-squat raises roll center, amplifying camber sensitivity—necessitating iterative kinematic simulation for balanced handling without compliance-induced hysteresis.[73]Tires, Wheels, and Contact Dynamics

Tires serve as the primary interface between the vehicle and the road, generating longitudinal, lateral, and vertical forces essential for acceleration, braking, cornering, and load support through deformation in the contact patch.[74] The contact patch, typically an elliptical area of rubber-road interaction spanning 100-200 cm² per tire under normal passenger car loads of 300-500 kg per wheel, determines the maximum available friction, with its shape and pressure distribution influenced by vertical load, inflation pressure, and tire construction.[74] Lower inflation pressure expands the patch area, increasing potential grip but risking uneven wear and reduced structural rigidity, while higher pressure narrows it, enhancing responsiveness at the cost of peak traction on low-mu surfaces.[75] Lateral forces for handling arise mainly from slip angle, the angular difference between the tire's longitudinal axis and its actual velocity vector, causing sidewall shear and brush-like deformation in the patch that shears rubber elements rearward, producing a force perpendicular to the heading.[74] In Pacejka's brush model, this force Fy increases near-linearly with small slip angles (0-5°) via cornering stiffness (typically 50-100 kN/rad for passenger tires), peaks around 6-12° due to friction saturation (μ ≈ 0.8-1.1 on dry asphalt), and then declines as sliding dominates.[74] Camber angle, the tilt of the wheel plane from vertical, induces camber thrust—a lateral force component from asymmetric patch loading and conicity—peaking at 1-3° of negative camber for most tires, aiding cornering by countering load transfer but diminishing at higher angles due to reduced vertical load sensitivity.[76] Combined slip conditions, blending longitudinal (κ) and lateral (α) inputs, reduce peak forces below isolated maxima, with friction ellipse models quantifying trade-offs (e.g., 20-30% grip loss under simultaneous braking and turning).[74] Wheels, comprising rims, hubs, and bearings, mount the tire and contribute to unsprung mass (typically 20-40 kg per corner, including tire), which resists rapid vertical motion and delays tire re-contact after bumps, degrading handling by prolonging slip excursions.[77] Reducing unsprung mass, such as via lightweight alloys (aluminum vs. steel, saving 5-10 kg per wheel), enhances suspension isolation, improving road-following and grip recovery rates by 10-20% in dynamic simulations.[77] Rotational inertia of the wheel-tire assembly (I ≈ 1-2 kg·m² for 15-17" diameters) demands additional driveline torque for acceleration or braking, with higher values (e.g., heavy steel wheels) increasing understeer propensity by slowing slip angle buildup.[78] Alignment parameters like toe and camber, set at the wheel, further tune contact dynamics, with slight toe-out (0.1-0.3°) on front wheels promoting turn-in responsiveness but accelerating inner tread wear.[74]Aerodynamics and Downforce

Aerodynamic forces significantly influence automobile handling by altering the vertical loads transmitted to the tires, which directly affect available grip through friction. Downforce, a downward-directed aerodynamic force, augments the normal force on the tires beyond the vehicle's static weight, thereby increasing maximum cornering acceleration, braking deceleration, and longitudinal traction, particularly at elevated speeds. This effect stems from the tire's grip capacity being proportional to the normal load, as governed by the coefficient of friction.[79] In contrast, aerodynamic lift—common in unmodified production sedans and SUVs—reduces tire loading and thus compromises stability and handling limits, often leading to reduced cornering speeds and increased susceptibility to rollover or loss of control.[80] Downforce is generated primarily through inverted airfoil shapes, such as rear wings, front splitters, and diffusers, which create low-pressure regions above the vehicle surfaces to produce a net downward force. In racing applications, ground-effect underbodies further enhance this by accelerating airflow beneath the car, amplifying downforce via the venturi principle. The force scales quadratically with vehicle speed (F_d ∝ v²), rendering it negligible at low speeds but dominant above approximately 100 km/h (62 mph), where it can exceed the vehicle's curb weight in high-performance configurations. For instance, typical lift coefficients (negative values indicating downforce) in race cars range from -0.4 to -0.6, depending on setup.[81] Studies on Formula Student vehicles demonstrate that downforce variations markedly alter handling metrics: a 33% increase in total downforce heightens grip sensitivity, with front-biased increases promoting understeer and rear-biased shifts inducing oversteer, as analyzed via computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and three-degree-of-freedom lateral dynamics models.[82] The balance between front and rear downforce critically determines steady-state handling behavior, analogous to static weight distribution. Excess front downforce elevates front axle load, reducing understeer tendency and enhancing turn-in responsiveness but potentially leading to oversteer on throttle application; conversely, rear emphasis stabilizes the rear but may induce understeer in corners. This balance is tuned via ride height, wing angles, and diffuser geometry, with simulations showing vehicle balance highly sensitive to front downforce distribution. Stability improves with front downforce due to higher yaw damping, while control (steering responsiveness) varies inversely with front loading. However, generating downforce incurs a drag penalty, as the same features that deflect air downward also resist forward motion, trading straight-line speed for cornering prowess—a core tension in motorsport aerodynamics where lift-to-drag ratios around 2.5 prioritize downforce over minimal drag.[84] In production vehicles, passive elements like spoilers provide modest downforce (e.g., 50-200 kg at highway speeds), but active systems—such as deployable rear wings—dynamically adjust for optimal handling without excessive low-speed drag.[85] Overall, while downforce elevates handling ceilings in controlled environments like racetracks, its speed dependency can disrupt balance in transitional regimes, necessitating integrated chassis tuning for consistent performance.Power Delivery, Braking, and Torque Management

Power delivery in automobiles affects handling primarily through its influence on longitudinal weight transfer and tire grip modulation during acceleration. Abrupt throttle inputs, especially in rear-wheel-drive configurations, can rapidly shift vehicle mass rearward, unloading the front tires and reducing steering responsiveness while increasing the risk of wheel spin or oversteer at the driven axle.[86] Smooth, progressive power application, conversely, allows controlled loading of the rear tires to enhance traction without destabilizing the chassis, as seen in performance driving techniques where throttle is modulated to maintain cornering balance.[87] In front-wheel-drive vehicles, excessive power delivery risks understeer by overwhelming front tire grip, limiting turn-in sharpness. Engine characteristics, such as torque curve shape, further dictate this: peaky high-rpm power bands demand precise rev-matching to avoid torque-induced instability, whereas flatter torque delivery—as in many modern turbocharged engines—facilitates more predictable handling.[86] Braking systems contribute to handling by enabling controlled deceleration that loads the front suspension, increasing front tire grip for improved turn-in during trail braking maneuvers. Without anti-lock braking systems (ABS), aggressive braking risks wheel lockup, which eliminates tire lateral force capacity and steering control, leading to directional instability—particularly evident in straight-line braking where uneven friction can cause drift or pull.[88] ABS mitigates this by cyclically modulating brake pressure to prevent lockup, preserving steering authority during emergency evasive actions; studies confirm that ABS-equipped vehicles maintain up to 20-30% better lateral control in combined braking-and-steering scenarios compared to non-ABS systems.[89] [90] In heavy vehicles, front brake bias interacts with load transfer to influence yaw stability, where improper distribution can amplify handling divergence under deceleration.[91] Advanced electronic braking, including electronic stability control integration, further refines this by adjusting individual wheel torque to counteract skid tendencies. Torque management systems, particularly active torque vectoring differentials, enhance handling by differentially distributing drive torque between wheels to induce yaw moments that aid cornering. In a torque-vectoring setup, more power is directed to the outer rear wheel during turns, accelerating it relative to the inner wheel to generate a rotational force that reduces understeer and sharpens turn-in, improving agility without relying solely on steering input.[92] This technique, implemented via clutch packs, electric motors, or brake interventions, can increase cornering speeds by optimizing tire slip angles and stability, as demonstrated in systems like Porsche's PTM where vectoring counters understeer proactively.[93] Brake-based torque vectoring, common in electronic limited-slip differentials, selectively applies friction to slow the inner wheel, mimicking mechanical vectoring effects to enhance traction exit from corners and mitigate oversteer in slippery conditions.[94] Such management extends to all-wheel-drive architectures, where front-rear torque split adjustments prevent power-induced torque steer, ensuring neutral handling balance across varying grip levels.[95]Steering and Frame Rigidity