Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chandi

View on Wikipedia

This article uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyse them. (February 2017) |

| Chandi | |

|---|---|

The fiery destructive power of Shakti | |

| Member of The Eight Matrika | |

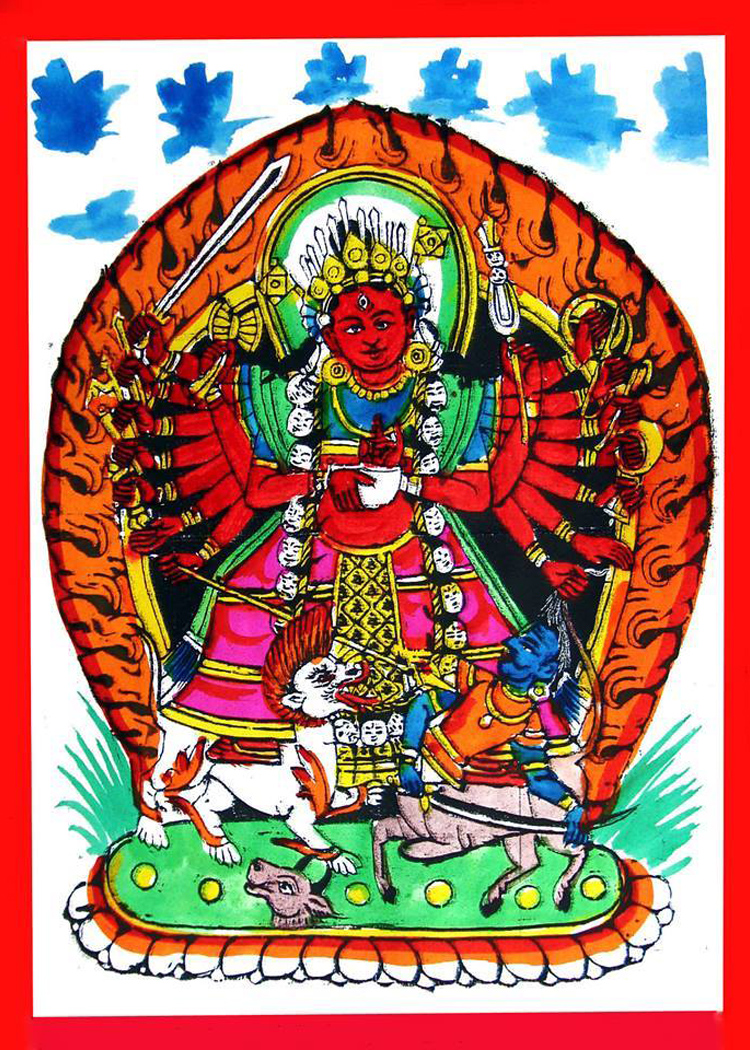

Newari portrayal of Chandi | |

| Devanagari | चण्डी |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Caṇḍī |

| Affiliation | |

| Mantra |

|

| Mount | Lion |

Chandi (Sanskrit: चण्डी, IAST: Caṇḍī) or Chandika (IAST: Caṇḍika) is a Hindu deity. Chandika is a form of goddess Durga.[1] She shares similarities with the Goddess Chamunda, not only in name but also in attributes and iconography. Due to these similarities, some consider them to be the same deity, while others view them as different manifestations of Mahadevi. Both are often associated with other powerful goddesses like Durga, Katyayani, Kali and Kalaratri. The Goddess is particularly revered in Gujarat.

History

[edit]In the Devī Māhātmya. Chandi represents the killer of Chanda. the Supreme Divine is often referred to as Caṇḍī or Caṇḍikā. This name is derived from the Sanskrit root caṇḍa, meaning “fierce” or “terrible.” Chandi is celebrated as the vanquisher of the demonic generals Chanda and Munda.[2] According to Bhaskararaya, a prominent authority on Devi worship, Chandi embodies divine wrath and passion.[3]

The epithet of Chandi or Chandika appears in the Devi Mahatmya, a text deeply rooted in the Shakta tradition of Bengal. This region has long been a significant center for Goddess worship and tantric practices. Since ancient times, it is the most common epithet used for the Goddess. Within the Devi Mahatmya, Chandi, Chandika, Ambika, and Durga are often used interchangeably to refer to the Supreme Goddess in the sect. [4][page needed]

Alongside the Sri Vidhya mantras, it is one of the principal mantras in Shakti worship. It is customary to chant this mantra when chanting the Devi Mahatmya. It is one of the primary mantras in the worship of Shakti. Traditionally, this mantra is chanted during recitations of the Devi Mahatmya. According to belief, the goddess resides in Mahakal, Kailasa.[5] The city of Chandigarh, the joint capital of Punjab and Haryana, is named after the Goddess.

Legends

[edit]She is known as the supreme goddess Mahishasuramardini or Katyayini Durga (6th Navadurga) who slayed the demon Mahishasura. She has been affiliated with and also considered as Vindhyavasini or Kaushiki or Yogmaya or Ambika who killed Shumbha, Nishumbha and their fellow demons.[6] "The great Goddess was born from the energies of the male divinities when the devas became impotent in the long-drawn-out battle with the asuras. All the energies of the Gods became united and became supernova, throwing out flames in all directions. Then that unique light, pervading the Three Worlds with its lustre, combined into one, and became a female form."[7][page needed]

"Devi projected overwhelming omnipotence. The three-eyed goddess was adorned with the crescent moon. Her multiple arms held auspicious weapons and emblems, jewels and ornaments, garments and utensils, garlands and rosaries of beads, all offered by the gods. With her golden body blazing with the splendour of a thousand suns, seated on her lion vehicle, Chandi is one of the most spectacular of all personifications of Cosmic energy."[8]

In other scriptures, Chandi is portrayed as "assisting" Kali in her battle with the demon Raktabīja. Chandi wounded him, but a new demon sprang up from every drop of his blood that fell on the ground. By drinking Raktabīja's blood before it could reach the ground, Kali enabled Chandi to first destroy the armies of demons and finally kill Raktabīja himself.[9] In Skanda Purana, this story is retold and another story of Mahakali killing demons Chanda and Munda is added.[10] Authors Chitralekha Singh and Prem Nath says, "Narada Purana describes the powerful forms of Lakshmi as Durga, Kali, Bhadrakali, Chandi, Maheshwari, Lakshmi, Vaishnavi and Andreye". Also, she is the one who purified Halahal (during Samudra Manthan) into Amrit (Ambrosio).[11]

Chandi Homa (Havan)

[edit]Chandi Homa is one of the most popular Homas in Hindu religion. It is performed across India during various festivals, especially during the Navaratri. Chandi Homa is performed by reciting verses from the Durga Sapthasathi and offering oblations into the sacrificial fire. It could also be accompanied by the Navakshari Mantra. Kumari Puja & Suvasini Puja also form a part of the ritual.[12][page needed]

Iconography

[edit]

The dhyana sloka preceding the Middle episode of Devi Mahatmya the iconographic details are given. The Goddess is described as having vermilion complexion, eighteen arms bearing string of beads, battle axe, mace, arrow, thunderbolt, lotus, bow, water-pot, cudgel, lance, sword, shield, conch, bell, wine-cup, trident, noose and the discus (sudarsana). She has a complexion of coral and is seated on a lotus.[13] In some temples the images of Maha Kali, Maha Lakshmi, and Maha Saraswati are kept separately. The Goddess is also portrayed as four armed in many temples.

In folklore of Bengal

[edit]Chandi is one of the most popular goddess in Bengal, and a number of poems and literary compositions in Bengali called Chandi Mangala Kavyas were written from 13th century to early 19th century.[14] These merged the local folk and tribal goddesses with mainstream Hinduism. The Mangal kavyas often associate Chandi with goddess Kali or Kalika[15] and recognise her as a consort of Shiva and mother of Ganesha and Kartikeya, which are characteristics of goddesses like Parvati and Durga.[16] The concept of Chandi as the supreme Goddess also underwent a change. The worship of the goddess became heterogeneous in nature.

Chandi is associated with good fortune. Her auspicious forms like Mangal Chandi, Sankat Mangal Chandi, Rana Chandi bestow joy, riches, children, good hunting and victory in battles while other forms like Olai Chandi cure diseases like cholera, plague and cattle diseases.[17]

These are almost all village and tribal Goddesses with the name of the village or tribe being added onto the name Chandi. The most important of these Goddesses is Mongol Chandi who is worshipped in the entire state and also in Assam. Here the word "Mongol" means auspicious or benign.[18]

See also

[edit]- Chandi di Var (in Sikhism)

- Candi of Indonesia

References

[edit]- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ "saptashatI". kamakotimandali.com. 28 December 2008. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016.

- ^ Coburn 1991, p. 134.

- ^ Coburn 1984.

- ^ Gopal 1990, p. 81.

- ^ Ramachander, P.R. (27 May 2008). "Goddess Parvathi" (PDF). stotraratna.awardspace.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2012.

- ^ Beane 1977.

- ^ Mookerjee 1988, p. 49.

- ^ Wilkins 1882, pp. 255–257.

- ^ Wilkins 1882, p. 260.

- ^ Singh & Nath 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Brown 1990.

- ^ Sankaranarayanan 2001, p. 148.

- ^ Stefon, Matt. "Chandi". Ancient Religions and Mythology. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ McDaniel 2004, p. 21.

- ^ McDaniel 2004, pp. 149–150.

- ^ McDaniel 2003, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Manna 1993, pp. 100–110.

Sources

[edit]- Beane, Wendell Charles (1977). Myth, Cult and Symbols in Sakta Hinduism: a study of the Indian Mother Goddess. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04814-0. OCLC 462282360.

- Brown, Cheever Mackenzie (1990). The Triumph of the Goddess: The Canonical Models and Theological Visions of the Devī-Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-585-07628-7. OCLC 42855925.

- Coburn, Thomas B. (1984). Devī Māhātmya: The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition. Delhi: Motilal Bonarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8364-0867-6. OCLC 643793128 – via Internet Archive.

- Coburn, Thomas B. (1991). Encountering the Goddess: A Translation of the Devi-Mahatmya and a Study of Its Interpretation. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-585-01691-7. OCLC 44964497 – via Internet Archive.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). India through the Ages. New Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India. OCLC 1157118397 – via Internet Archive.

- Manna, Sibendu (1993). Mother Goddess Caṇḍī: Its Socio Ritual Impact on the Folk Life. Calcutta: Punthi Pustak. ISBN 978-81-85094-60-1. OCLC 29595373.

- McDaniel, June (2003). Making Virtuous Daughters and Wives: An Introduction to Women's Brata Rituals in Benegal Folk Religion. New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4175-0860-0. OCLC 55642408 – via Internet Archive.

- McDaniel, June (2004). Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-4237-5659-0. OCLC 64685459 – via Internet Archive.

- Mookerjee, Ajit (1988). Kali: The Feminine Force. New York: Destiny Books. ISBN 978-0-89281-212-7. OCLC 1035908837 – via Internet Archive.

- Sankaranarayanan (2001) [1968]. Glory Of The Divine Mother Devi Mahatmyam. India: Nesma Books. ISBN 978-81-87936-00-8. See also: OCLC 878083089

- Singh, Chitralekha; Nath, Prem (2001). Lakshmi. New Delhi: Crest Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-242-0173-2. OCLC 59302249.

- Wilkins, William Joseph (1882). Hindu mythology, Vedic and Purānic. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co. hdl:2027/ia.ark:/13960/t2x34v844. OCLC 1085344444 – via HathiTrust.

External links

[edit]Chandi

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Origins

Name and Epithets

Chandi, also spelled Caṇḍī or rendered as Candika, is the primary name by which the supreme goddess is invoked in the Devi Mahatmya, a foundational Shakta text within the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa. The term derives from the Sanskrit root caṇḍ, connoting fierceness, violence, or wrathful intensity, symbolizing the goddess's embodiment of unyielding divine power directed against cosmic evil. This etymology underscores her role as the "violent and impetuous one," a manifestation of Shakti that integrates destructive and protective energies to uphold dharma.[7][8] In the Devi Mahatmya, Chandi is not a singular appellation but part of a rich nomenclature reflecting her multifaceted nature, with epithets often used synonymously to evoke her as the ultimate reality (parabrahman). These names appear across the text's hymns and narratives, emphasizing her supremacy as the source of creation, preservation, and annihilation. Scholarly analysis, such as in Devadatta Kali's commentary, highlights how these epithets blend Vedic sovereignty with Tantric nondualism, portraying Chandi as the projector of all cosmic forces.[7][9] Key epithets include Ambika, denoting the maternal aspect that nurtures and incinerates foes (Devi Mahatmya 4.3, 4.24); Durga, signifying an impregnable fortress against adversity and the slayer of the demon Mahiṣāsura (Devi Mahatmya 4.11, 11.50); and Kālī, the dark, time-devouring form emerging in battle with emaciated features and bloodied fangs (Devi Mahatmya 7.6–15). Other prominent ones are Mahāmāyā, the great illusion-weaver who deludes enemies (Devi Mahatmya 1.55); Nārāyaṇī, evoking universal consciousness and protection in the Nārāyaṇī Stuti (Devi Mahatmya 11.3–35); and Cāmuṇḍā, a nickname for Kālī post-victory over the demons Caṇḍa and Muṇḍa (Devi Mahatmya 7.27). These terms collectively affirm Chandi's identity as the singular divine feminine principle, beyond duality, as articulated in Tantric interpretations where she is the supreme consciousness (citśakti).[7] The following table summarizes select epithets from the Devi Mahatmya, their meanings, and contextual significance:| Epithet | Meaning and Derivation | Significance in Devi Mahatmya | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caṇḍikā | Fierce or wrathful (from caṇḍ) | Supreme power annihilating demons; highest Brahman | 3.28, 7.26, 11.50 |

| Ambikā | Mother or primal one | Maternal protector reducing enemies to ashes | 4.3, 6.66–67 |

| Durgā | Impenetrable or difficult of access | Invincible warrior against chaos | 4.11, 11.20–23 |

| Kālī | Dark or time (from kāla) | Destructive force in battles, embodying eternal cycle | 7.9–15, 7.58 |

| Mahāmāyā | Great deluder | Cosmic illusion controlling minds and fates | 1.55, 11.31 |

| Nārāyaṇī | Belonging to the universal lord | Omniscient guardian of dharma and liberation | 11.8, 11.98 |