Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cholesteric liquid crystal

View on WikipediaThis article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (April 2025) |

Cholesteric liquid crystals (ChLCs), also known as chiral nematic liquid crystals, are a supramolecular assembly and a subclass of liquid crystal characterized by their chirality. Contrary to achiral liquid crystals, the common orientational direction of ChLCs (known as the director) is arranged in a helix whose axis of rotation is perpendicular to the director in each layer. ChLCs can be thermotropic and lyotropic. ChLCs are formed from a variety of anisotropic molecules, including chiral small molecules and polymers. ChLCs can be also formed by introducing a chiral dopant at low concentrations into achiral liquid crystalline phases.[1]

Examples of ChLCs range from scarab beetle shells to liquid crystal displays.[2] Many natural molecules and polymers spontaneously form the cholesteric phase. ChLCs have been used to manufacture products ranging from smart paints to textiles to and sensors. Scientists often employ biomimicry to develop ChLC-based materials inspired by natural examples.[3]

History

[edit]

Cholesteric liquid crystals (ChLCs) have a history dating back nearly 150 years. In 1888, the first liquid crystal — cholesteryl benzoate, a thermotropic ChLC [4] — was discovered by Austrian botanist and chemist Friedrich Reinitzer.[5] Although he initially believed that cholesteryl benzoate consisted of aggregates of tiny, flowing crystals, he was confounded by the presence of two melting points. The first transition (around 145-146 °C) corresponded to a phase transition to a liquid state that possessed vibrant colors, and the second high-temperature melting point (178-180 °C) changed this cloudy liquid to a clear melt. He also discovered that this process was fully reversible.[6] These discoveries Reinitzer reported in what is recognized as the first paper on liquid crystals.[1]

Reinitzer was a close collaborator with Otto Lehmann, along with whom Reinitzer is considered the "father" of liquid crystals.[1] Lehmann was the inventor of the first hot stage microscope capable of studying the thermal properties of thermotropic ChLCs, which he created in 1876.[5] One of the key features of his microscope was crossed-polarizers. Polarized light microscopy remains highly important in the study of liquid crystals, including ChLCs.[1] While Reinitzer quickly lost interest in the substances, Lehmann continued studying his apparently "flowing crystals" on his hot stage microscope, realizing they exhibited orientationally-dependent, vibrant colors under crossed polarizers.[1][7] Lehmann was the first to coin the term liquid crystal.[8] Studies in liquid crystals soon blossomed, and in 1922 Georges Friedel created the classification system of liquid crystals still used today. In this system, he named the chiral variety of liquid crystals cholesteric, as they were discovered from a cholesterol derivative.[5][9]

Liquid crystals emerged from the status of a curiosity necessitating high temperatures to function in the 1960s, with the advent of liquid crystal display technology.[1] Although liquid crystal displays (LCDs) are typically made of nematic liquid crystals, ChLCs have been utilized in display technology. Examples include a thermal sensor range meter created by James Fergason using ChLCs in 1959, an invention which was patented in 1960.[10] Another example is a stress-sensing card, which when applied to skin — ordinarily black — becomes blue when the wearer is relaxed and red when stressed. The technology relies on body temperature differences between relaxation and stress.[11]

Theory

[edit]Structure

[edit]

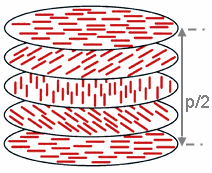

Due to their properties intermediate between pure liquids and crystalline solids, liquid crystals are known as mesogens, a name deriving from Greek for mésos, or "intermediate". The property underpinning all liquid crystals is anisotropy (directional nonuniformity, typically manifested by an elongated rodlike shape), which under appropriate conditions (ex. high temperatures and concentrations) allows for local order around a preferred axis, named the director.[1] Cholesteric liquid crystals are no exception. Like nematic liquid crystals, ChLCs exhibit a medium-range director along which the long axis of the liquid crystals are arranged. Unlike nematics, along a twist axis perpendicular to the director, ChLCs are arranged in layers that rotate with helical pitch p, typically defined as twice the periodicity along the twist axis.[12]

There exist two classes of liquid crystals based on the conditions under which they form: thermotropic and lyotropic. Thermotropic liquid crystals undergo phase transitions based on temperature, whereas lyotropic liquid crystalline phases transition based on concentration within a solvent, most commonly water.[13] For example, 5CB — a classic example of an achiral nematic thermotropic LC — undergoes an isotropic-nematic transition at 308K and a nematic-crystalline transition at 252K.[14] Similarly, poly(n-hexyl isocyanate), a lyotropic liquid crystal, undergoes the analogous isotropic-nematic transition at weight fractions ranging from 0.225 to 0.438 in toluene, depending on molecular weight of the polymer.[15] Cholesteric liquid crystals comprise both classes. Both small molecules and polymers can form cholesteric liquid crystals. In nature, examples include DNA, chitin, cellulose, and collagen, among others.[2]

The local ordering in both nematic and ChLCs can be characterized according to the local nematic order parameter S. This parameter is formulated according to the following equation, a rank-2 tensor:[16]

Here, for an anisotropic molecule, the nematic order tensor is a function of number of molecules N, the outer product of the unit vector along the long axis v(i), and a traceless correction term, the Kronecker delta δ.[16] The largest eigenvalue of the resulting tensor is the local nematic order. For an isotropic sample, the nematic order will be calculated as 0. For a fully-ordered sample, the nematic order approaches 1. Typically, the cholesteric pitch ranges in values from as small as 100nm to several micrometers.[17] The orientation of the nematic director at a certain distance along the director twist axis (usually defined as the z-axis in Cartesian coordinates) is:

Here, q is defined as the helicity of a ChLC, . The helicity is positive for a right-handed cholesteric helix, and negative for left-handed helices.[18] The origin of the helical pitch can be described with Frank-Oseen elastic free energy density:

Where div is the divergence for a vector field n (representing the individual molecular long-axis vectors) and curl is the curl of the same vector field. In 3D space, with unit vectors i, j, and k along each coordinate axis. The constants K are known as Frank elastic constants, and are empirical.[12] By minimizing the free energy, we obtain an expression for the cholesteric helicity q.

Inducement of chirality

[edit]

ChLCs can form either from intrinsically chiral molecules or polymers or can be formed via chiral-dopant mediated processes. An example of a chiral-dopant mediated process is poly(n-hexyl isocyanate) (PHIC). PHIC, which is a helical polymer that is typically racemic and exhibits a nematic liquid crystalline phase due to the presence of dynamic helix-flips (ie. where the helix flips its handedness),[19] becomes cholesteric when exposed to a small amount of chiral dopant. The mechanism by which this transition occurs is via the slight displacement of the racemic mixture to a small enantiomeric excess, which then drives the formation of cholesteric helices.[20]

Different chiral dopants may be quantitatively compared using their empirical helical twisting power:

Where C is the mole fraction of the dopant, corrected for enantiomeric purity.[21] Dopants also induce chirality on small molecules by biasing a specific chiral spatial configuration, which has an amplifying effect that ultimately leads to the formation of a chiral phase from a small enantiomeric biasing.[22]

An example of inherently chiral ChLCs is poly-γ-benzyl-l-glutamate (PBLG), a lyotropic liquid crystal that forms cholesteric phases without dopant.[23] This is attributed to the strong α-helix formed between individual peptides, whose handedness arises from homochiral monomers during synthesis.[24] Examples of small-molecule ChLCs include cholesterol-doped 5CB and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine.[25] The pitch of thermotropic ChLCs is temperature-dependent.[26]

Optical Textures

[edit]Due to their anisotropy, liquid crystals are birefringent. Formally, this means that the index of refraction is directionally dependent, with characteristic indices defined along perpendicular optical axes. Upon incident light, these different indices break up the waves into multiple with different wavelengths.[1]

When observed under a polarized optical microscope, ChLCs can create a number of textures due to a combination of their inherent birefringence and their relative alignment with the incident light. To relate the pitch with the observed textures, the Bragg equation is used:

Where n is the average refractive index of the birefringent material and Φ is the observation angle. Therefore, the pitch of the ChLC influences the observed texture.[27]

Among the most common textures is the oily streak texture, which was the first texture experimentally observed in cholesteryl benzoate.[6] This texture arises when the director helix axis is parallel to the incident light, and manifests as small streaks of birefringence against a dark background under crossed polarizers. If the pitch is very short, this orientation can also give rise to the Grandjean texture.[17] This texture appears monochromic under crossed-polarizers.[28]

Another texture is the classical fingerprint texture, where the director helix axis is perpendicular to incident light. Here, the cholesteric helix can be easily observed and measured, as the pitch is calculated as the distance between two dark fringes.[29] This information can be used to measure helical twisting power of the liquid crystal or monitor changes to the physical structure of the cholesteric helix in applications such as optical sensing.[21][30] Particularly long pitches arranged this way give rise to the focal-conic texture.[31]

The textures can be tuned with external stimuli. Pijper and coworkers invented a ChLCs whose pitch can be dynamically controlled via light irradiation. A chiral, photoswitchable chromophore was functionalized onto the ends of PHIC polymers, whose enantiomeric excess could be tuned with irradiation time. Upon irradiation with characteristic wavelengths of light, the texture changed from fingerprint to nematic to the opposite-handed fingerprint.[30]

Characterization

[edit]By nature, cholesteric liquid crystals share a significant number of characterization methods with achiral liquid crystalline phases. Some are highlighted:

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

[edit]Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is a technique that measures heat flow differences between a sample and a reference.[32] In the case of thermotropic liquid crystals, DSC can determine the presence of phase transitions between isotropic and cholesteric, and cholesteric and other phases. This double melting point is characteristic of the liquid crystalline phase.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

[edit]Like in nematic liquid crystals, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can be used to probe the supramolecular structure of ChLCs.[14] Due to the relative orientation of quadrupole moments in individual molecules, NMR can observe characteristic peak splitting that evolves with temperature and phase changes. For example, NMR studies of cholesteryl alkanoates found that cooling the isotropic phase to the smectic phase (a phase where molecules are arranged in discrete planes) via the cholesteric phase showed a singlet peak become increasingly split with decreasing temperature and increasing local order.[33]

Polarized Light Microscopy

[edit]

Due to the birefringence of liquid crystalline samples, liquid crystals display vivid characteristic textures under cross-polarizers (note that isotropic samples will be completely dark under crossed polarizers).[1] These textures are typically characteristic of the studied phase, meaning that ChLCs can be qualitatively identified by simple microscopy. On top of allowing for qualitative phase assignment, the cholesteric pitch can be quantitatively determined by simple measurement of the fringe displacement in the fingerprint texture.[17]

Polarized light microscopy is widely used in studies of liquid crystals.[34] However, textures are reliant on the surfaces by which they are confined — that is, their relative alignment with incident light. In order to provide control for alignment, adsorbents such as octadecyltrichlorosilane (OTS) have been proposed to create self-assembled monolayers on the glass surface. These monolayers then act as aligners for the bulk liquid crystalline mesophase.[35]

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

[edit]Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy characterizes chiral materials by differential absorption of left and right handed circularly-polarized light.[36] In the context of ChLCs, CD spectroscopy can distinguish between different helical senses — for example, a cholesteric helix that primarily transmits left-handed circularly polarized light is considered left-handed. The CD spectrum is also dependent on other quantities associated with the supramolecular helix, such as pitch and orientation/texture with respect to incident light.[37]

Examples and Applications

[edit]Helical Templates

[edit]The helical structure of ChLCs can serve as templates to induce supramolecular helical structures in otherwise-structureless dopants. When the dopant is introduced into a liquid crystalline matrix, it self-assembles into the empty spaces between helices, creating helical structures. For example, Li and coworkers templated latex nanoparticles in a matrix of cholesteric cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs). These nanoparticles arranged into the cholesteric defects, creating helicoidal nanoparticle assemblies.[38]

Natural Mimics

[edit]ChLCs are widely present in nature. Many biological polymers such as DNA, chitin, cellulose, collagen, and certain viruses (for example, filamentous bacteriophages)[39] can exhibit cholesteric phases naturally, or via dopant-mediated processes.[2]

Natural selection has favored the natural development of ChLCs in some beetle shells.[40] The classic metallic sheen of scarab beetle genera such as plusiotis arises from ChLCs — mostly chitin — in their shells.[3] The appealing aesthetics of these insects have led scientists to pursue nature-inspired design of ChLC-based products ranging from mood rings to nail polish, mimicking scarab beetle sheen.[41]

Color-Changing Films

[edit]Kizhakidathazhath and coworkers invented a color-changing film based on cholesteric liquid crystal elastomers (ChLCE). Formed from lyotropic ChLCs, dry films with a frozen cholesteric helix were created by rapid solvent evaporation followed by photocrosslinking of the resulting gel. This thin film is mechanochromically responsive, changing colors with stress and bending.[42]

Smart Textiles

[edit]Kao and coworkers incorporated ChLC microspheres into a polyvinyl alcohol matrix. The composite was found to have superior mechanical properties compared to raw polyvinyl alcohol, and remained color stable even under extreme conditions, such as high electric field. The composite was able to be spun into thin fibers.[43]

Similarly, Geng and coworkers created ChLCE-based spinnable fibers that exhibit mechanochromic responses, changing colors from red to blue with increasing strain.[44]

Smart Paints

[edit]Ko and coworkers invented a smart color-changing paint whose color is both tunable and subsequently freezable using ultraviolet (UV) light. Starting with an achiral photopolymerizable monomer precursor, chiral dopants were added to tune the pitch (according to the aforementioned helical twisting power equation), allowing for colorimetric tuning. Upon irradiation with UV light, the monomers polymerized, creating freestanding colored films with frozen molecular arrangement. The authors were able to create red, green, and blue films using this method.[45]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i DiLisi, Gregory A (2019-09-01). Deluca, James J. (ed.). An Introduction to Liquid Crystals. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. Bibcode:2019ilc..book.....D. doi:10.1088/2053-2571/ab2a6f. ISBN 978-1-64327-684-7.

- ^ a b c Mitov, Michel (2017). "Cholesteric liquid crystals in living matter". Soft Matter. 13 (23): 4176–4209. Bibcode:2017SMat...13.4176M. doi:10.1039/c7sm00384f. ISSN 1744-683X. PMID 28589190.

- ^ a b Neville, A. C.; Caveney, S. (1969). "Scarabaeid Beetle Exocuticle as an Optical Analogue of Cholesteric Liquid Crystals". Biological Reviews. 44 (4): 531–562. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1969.tb00611.x. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 5308457.

- ^ Itahara, Toshio; Furukawa, Shushi; Kubota, Kaoru; Morimoto, Mayumi; Sunose, Miho (2013-05-01). "Cholesteryl benzoate derivatives: synthesis, transition property and cholesteric liquid crystal glass". Liquid Crystals. 40 (5): 589–598. Bibcode:2013LoCr...40..589I. doi:10.1080/02678292.2013.776707. ISSN 0267-8292.

- ^ a b c Sparavigna, Amelia Carolina (2019-08-10). "The Earliest Researches on Liquid Crystals". HAL Open Science. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.3365347.

- ^ a b Reinitzer, Friedrich (1888-12-01). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss des Cholesterins". Monatshefte für Chemie und verwandte Teile anderer Wissenschaften (in German). 9 (1): 421–441. doi:10.1007/BF01516710. ISSN 1434-4475.

- ^ Lehmann, O. (1889-01-01). "Über fliessende Krystalle". Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 4 (1). doi:10.1515/zpch-1889-0134. ISSN 2196-7156.

- ^ Chandrasekhar, S. (1988-11-01). "Recent developments in the physics of liquid crystals". Contemporary Physics. 29 (6): 527–558. Bibcode:1988ConPh..29..527C. doi:10.1080/00107518808222607. ISSN 0010-7514.

- ^ Friedel, G. (1922). "Les états mésomorphes de la matière". Annales de Physique. 9 (18): 273–474. Bibcode:1922AnPh....9..273F. doi:10.1051/anphys/192209180273. ISSN 0003-4169.

- ^ Ennulat, R. D.; Fergason, J. L. (1971-05-01). "Thermal Radiography Utilizing Liquid Crystals". Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals. 13 (2): 149–164. Bibcode:1971MCLC...13..149E. doi:10.1080/15421407108084960. ISSN 0026-8941.

- ^ Kawamoto, H. (2002). "The history of liquid-crystal displays". Proceedings of the IEEE. 90 (4): 460–500. Bibcode:2002IEEEP..90..460K. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2002.1002521. ISSN 1558-2256.

- ^ a b Kléman, Maurice; Laverntovich, Oleg D. (2003). Soft Matter Physics: An Introduction. Partially Ordered Systems (1st ed. 2003 ed.). New York, NY: Imprint: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-95267-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Hiltrop, K. (1994), "Lyotropic Liquid Crystals", Liquid Crystals, Heidelberg: Steinkopff, pp. 143–171, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-08393-2_4, ISBN 978-3-662-08395-6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ a b Mansaré, T.; Decressain, R.; Gors, C.; Dolganov, V. K. (2002-01-01). "Phase Transformations And Dynamics Of 4-Cyano-4′-Pentylbiphenyl (5cb) By Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Analysis Differential Scanning Calorimetry, And Wideangle X-Ray Diffraction Analysis". Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals. 382 (1): 97–111. Bibcode:2002MCLC..382...97M. doi:10.1080/713738756. ISSN 1542-1406.

- ^ Itou, Takashi; Teramoto, Akio (1988). "Isotropic-liquid crystal phase equilibrium in solutions of semiflexible polymers: poly(hexyl isocyanate)". Macromolecules. 21 (7): 2225–2230. Bibcode:1988MaMol..21.2225I. doi:10.1021/ma00185a058. ISSN 0024-9297.

- ^ a b Stephen, Michael J.; Straley, Joseph P. (1974-10-01). "Physics of liquid crystals". Reviews of Modern Physics. 46 (4): 617–704. Bibcode:1974RvMP...46..617S. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.46.617.

- ^ a b c Dierking, Ingo (2003-05-27). Textures of Liquid Crystals. Wiley. doi:10.1002/3527602054. ISBN 978-3-527-30725-8.

- ^ Kimura, H.; Hosino, M.; Nakano, H. (1979-04-01). "Temperature Dependent Pitch in Cholesteric Phase". Le Journal de Physique Colloques. 40 (C3): C3–177. doi:10.1051/jphyscol:1979335. ISSN 0449-1947.

- ^ Shah, Priyank N.; Min, Joonkeun; Chae, Chang-Geun; Nishikawa, Naoki; Suemasa, Daichi; Kakuchi, Toyoji; Satoh, Toshifumi; Lee, Jae-Suk (2012-11-07). ""Helicity Inversion": Linkage Effects of Chiral Poly(n-hexyl isocyanate)s". Macromolecules. 45 (22): 8961–8969. Bibcode:2012MaMol..45.8961S. doi:10.1021/ma301930s. ISSN 0024-9297.

- ^ Green, Mark M.; Zanella, Stefania; Gu, Hong; Sato, Takahiro; Gottarelli, Giovanni; Jha, Salil K.; Spada, Gian Piero; Schoevaars, Anne Marie; Feringa, Ben; Teramoto, Akio (1998-09-01). "Mechanism of the Transformation of a Stiff Polymer Lyotropic Nematic Liquid Crystal to the Cholesteric State by Dopant-Mediated Chiral Information Transfer". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 120 (38): 9810–9817. Bibcode:1998JAChS.120.9810G. doi:10.1021/ja981393t. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ a b GOTTARELLI, G.; HIBERT, M.; SAMORI, B.; SOLLADIE, G.; SPADA, G. P.; ZIMMERMANN, R. (1984-03-13). "ChemInform Abstract: INDUCTION OF THE CHOLESTERIC MESOPHASE IN NEMATIC LIQUID CRYSTALS: MECHANISM AND APPLICATION TO THE DETERMINATION OF BRIDGED BIARYL CONFIGURATIONS". Chemischer Informationsdienst. 15 (11) chin.198411069. doi:10.1002/chin.198411069. ISSN 0009-2975.

- ^ Samulski, E. T.; Tobolsky, A. V. (1970), "Cholesteric and Nematic Structures of Poly-γ-Benzyl-L-Glutamate", Liquid Crystals and Ordered Fluids, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 111–121, doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-8214-0_8, ISBN 978-1-4684-8216-4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Samulski, E. T.; Tobolsky, A. V. (1970), "Cholesteric and Nematic Structures of Poly-γ-Benzyl-L-Glutamate", Liquid Crystals and Ordered Fluids, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 111–121, doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-8214-0_8, ISBN 978-1-4684-8216-4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Guo, Jinshan; Huang, Yubin; Jing, Xiabin; Chen, Xuesi (2009). "Synthesis and characterization of functional poly(γ-benzyl-l-glutamate) (PBLG) as a hydrophobic precursor". Polymer. 50 (13): 2847–2855. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2009.04.016. ISSN 0032-3861.

- ^ Popov, Piotr; Mann, Elizabeth K.; Jákli, Antal (2017). "Thermotropic liquid crystal films for biosensors and beyond". Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 5 (26): 5061–5078. doi:10.1039/c7tb00809k. ISSN 2050-750X. PMID 32264091.

- ^ KIMURA, H.; HOSINO, M.; NAKANO, H. (1979). "Temperature Dependent Pitch in Cholesteric Phase". Le Journal de Physique Colloques. 40 (C3): C3–174-C3-177. doi:10.1051/jphyscol:1979335. ISSN 0449-1947.

- ^ Hu, Jian-She; Zhang, Bao-Yan; Liu, Lu-Mei; Meng, Fan-Bao (2003-07-18). "Synthesis, structures, and properties of side-chain cholesteric liquid-crystalline polysiloxanes". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 89 (14): 3944–3950. doi:10.1002/app.12690. ISSN 0021-8995.

- ^ Watanabe, Junji; Nagase, Tatsuya; Itoh, Hiroyuki; Ishii, Takafumi; Satoh, Tetsuo (1988). "Thermotropic Polypeptides. 6. On Cholesteric Mesophase with Grandjean Texture and its Solidification". Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals Incorporating Nonlinear Optics. 164 (1): 135–143. Bibcode:1988MCLCI.164..135W. doi:10.1080/00268948808072118. ISSN 1044-1859.

- ^ Cladis, P. E.; Kléman, M. (1972). "The Cholesteric Domain Texture". Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals. 16 (1–2): 1–20. Bibcode:1972MCLC...16....1C. doi:10.1080/15421407208083575. ISSN 0026-8941.

- ^ a b Pijper, Dirk; Jongejan, Mahthild G. M.; Meetsma, Auke; Feringa, Ben L. (2008-04-01). "Light-Controlled Supramolecular Helicity of a Liquid Crystalline Phase Using a Helical Polymer Functionalized with a Single Chiroptical Molecular Switch". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (13): 4541–4552. Bibcode:2008JAChS.130.4541P. doi:10.1021/ja711283c. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 18335940.

- ^ Dolganov, P. V.; Baklanova, K. D.; Dolganov, V. K. (2022-07-13). "Peculiarities of focal conic structure formed near the cholesteric-isotropic phase transition". Physical Review E. 106 (1) 014703. Bibcode:2022PhRvE.106a4703D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.106.014703. PMID 35974502.

- ^ "Differential Scanning Calorimetry". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2025-02-21.

- ^ Luz, Z.; Poupko, R.; Samulski, E. T. (1981-05-15). "Deuterium NMR and molecular ordering in the cholesteryl alkanoates mesophases". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 74 (10): 5825–5837. Bibcode:1981JChPh..74.5825L. doi:10.1063/1.440897. ISSN 0021-9606.

- ^ Bellare, J. R; Davis, H. T; Miller, W. G; Scriven, L. E (1990-05-01). "Polarized optical microscopy of anisotropic media: Imaging theory and simulation". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 136 (2): 305–326. Bibcode:1990JCIS..136..305B. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(90)90379-3. ISSN 0021-9797.

- ^ Roscioni, Otello Maria; Muccioli, Luca; Zannoni, Claudio (2017-04-05). "Predicting the Conditions for Homeotropic Anchoring of Liquid Crystals at a Soft Surface. 4-n-Pentyl-4′-cyanobiphenyl on Alkylsilane Self-Assembled Monolayers". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 9 (13): 11993–12002. Bibcode:2017AAMI....911993R. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b16438. ISSN 1944-8244. PMID 28287693.

- ^ "Circular Dichroism". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2025-02-21.

- ^ Saeva, F. D. (1974), "Some Mechanistic Aspects of the Cholesteric Liquid Crystal Induced Circular Dichroism (LCICD) Phenomenon", Liquid Crystals and Ordered Fluids, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 581–592, doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-2727-1_51, ISBN 978-1-4684-2729-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Li, Yunfeng; Prince, Elisabeth; Cho, Sangho; Salari, Alinaghi; Mosaddeghian Golestani, Youssef; Lavrentovich, Oleg D.; Kumacheva, Eugenia (2017-02-28). "Periodic assembly of nanoparticle arrays in disclinations of cholesteric liquid crystals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (9): 2137–2142. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.2137L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1615006114. PMC 5338481. PMID 28193865.

- ^ Tang, Jianxin; Fraden, Seth (1995-10-01). "Isotropic-cholesteric phase transition in colloidal suspensions of filamentous bacteriophage fd". Liquid Crystals. 19 (4): 459–467. Bibcode:1995LoCr...19..459T. doi:10.1080/02678299508032007. ISSN 0267-8292.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (2013-07-12). "Diverse Crystals Account for Beetle Sheen". Science. 341 (6142): 120. doi:10.1126/science.341.6142.120. PMID 23846885.

- ^ Lenau, Torben A.; Aggerbeck, Martin; Nielsen, Steffen (2009-08-20). "Approaches to mimic the metallic sheen in beetles". In Martin-Palma, Raul J.; Lakhtakia, Akhlesh (eds.). Biomimetics and Bioinspiration (PDF). Vol. 7401. SPIE. p. 740107. doi:10.1117/12.826227.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Kizhakidathazhath, Rijeesh; Geng, Yong; Jampani, Venkata Subba Rao; Charni, Cyrine; Sharma, Anshul; Lagerwall, Jan P. F. (2020). "Facile Anisotropic Deswelling Method for Realizing Large-Area Cholesteric Liquid Crystal Elastomers with Uniform Structural Color and Broad-Range Mechanochromic Response". Advanced Functional Materials. 30 (7) 1909537. doi:10.1002/adfm.201909537. ISSN 1616-3028.

- ^ Kao, Tzu-Hsun; Hsu, Hsun-Hao; Chen, Jui-Juin; Lee, Lin-Ruei; Chen, Hui-Yu; Chen, Jiun-Tai (2024-07-09). "Fabrication of Polymer/Cholesteric Liquid Crystal Films and Fibers Using the Nonsolvent and Phase Separation Method". Langmuir. 40 (27): 14166–14172. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.4c01759. ISSN 0743-7463. PMC 11238578. PMID 38916980.

- ^ Geng, Yong; Kizhakidathazhath, Rijeesh; Lagerwall, Jan P. F. (2022). "Robust cholesteric liquid crystal elastomer fibres for mechanochromic textiles". Nature Materials. 21 (12): 1441–1447. Bibcode:2022NatMa..21.1441G. doi:10.1038/s41563-022-01355-6. ISSN 1476-4660. PMC 9712110. PMID 36175519.

- ^ Ko, Hyeyoon; Kim, Minwook; Wi, Youngjae; Rim, Minwoo; Lim, Seok-In; Koo, Jahyeon; Kang, Dong-Gue; Jeong, Kwang-Un (2021-08-10). "Chiroptical Smart Paints: Polymerization of Helical Structures in Cholesteric Liquid Crystal Films". Journal of Chemical Education. 98 (8): 2649–2654. Bibcode:2021JChEd..98.2649K. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00168. ISSN 0021-9584.