Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Climate communication

View on Wikipedia

Climate communication or climate change communication is a field of environmental communication and science communication focused on discussing the causes, nature and effects of anthropogenic climate change.

Research in the field emerged in the 1990s and has since grown and diversified to include studies concerning the media, conceptual framing, and public engagement and response. Since the late 2000s, a growing number of studies have been conducted in countries in the Global South and have been focused on climate communication with marginalized populations.

Most research focuses on raising public knowledge and awareness, understanding underlying cultural values and emotions, and bringing about public engagement and action. Major issues include familiarity with the audience, barriers to public understanding, creating change, audience segmentation, changing rhetoric, public health, storytelling, media coverage, and popular culture.

History

[edit]Scholar Amy E. Chadwick identifies Climate Change Communication as a new field of scholarship that truly emerged in the 1990s.[4] In the late 80s and early 90s, research in developed countries (e.g. the United States, New Zealand, and Sweden) was largely concerned with studying the public's perception and comprehension of climate change science, models, and risks and guiding further development of communication strategies.[4][5] These studies showed that while the public was aware of and beginning to notice climate change effects (increasing temperatures and changing precipitation patterns), the public's understanding of climate change was interlinked with ozone depletion and other environmental risks but not human-produced CO2 emissions.[5] This understanding was coupled with varied yet overall increased net concern that continued through the mid-2000s.[5]

In studies from the mid-2000s to the late 2000s, there is evidence of rising global skepticism despite growing consensus and evidence of increasingly polarized views due to climate change's growing use as a political "litmus test."[5] In 2010, researcher Susanne C. Moser viewed both the expansion of climate change communication's focus, which began to include subjects such as materialized evidence of climate change effects in addition to science and policy, as well as more prolific conversation/communication from a variety of voices as increasing climate change's relevance to society.[6] Surveys through the mid-2010s showed mixed concern for climate change depending on global region —notably consistent concern in developed Western countries but a trend towards global unconcern in countries such as China, Mexico, and Kenya.[5]

In 2016, Moser noted an increase in the total number of climate communication studies in both Westernized countries and the Global South and an increased focus on climate communication with indigenous peoples and other marginalized communities since 2010.[7] As of 2017, research remained focused on public understanding and had since begun to also analyze the relevance of the media, conceptual framing, public engagement and response, and persuasive strategies.[4][7] This expansion has legitimated climate change communication as its own academic field and has yielded a group of experts specific to it.[7]

Primary goals of climate communication

[edit]

Most climate communication and research within the field is concerned with (1) the mechanisms related to the public's understanding/awareness of and perception of climate change which are intertwined with (2) personal cultural values and emotions related to social norms and (3) how these components can influence the engagement and action that may emerge as a response to communication.[4][6][8]

Within the academic field, there are debates over which is more important: knowledge-based communication or emotion-driven communication.[9] Though both are inherently linked to action, researchers often view increased understanding as leading to increased action.[9][10] A 2020 study by Kris De Meyer et al. attempts to push back against that notion and argues that action produces belief.[9]

Analyzing and increasing public understanding and perception

[edit]One line of climate communication study is concerned with analyzing public understanding and risk perception.[4] Understanding public perception of risk and its relevant influences, as well as public knowledge, concern, consensus, and imagery is thought to help policymakers better address the concerns of constituents and inform further climate communication.[4][10][11] This notion has opened the realm of climate communications to political communications, sociology, and psychology.[11]

Achieving increased public understanding is often associated with communicating levels of scientific consensus and other scientific facts or futures in order to spur action and address the "information-deficit" model but can also be related to connecting with values and emotions.[9][11] Perception is often related to personal recognition to impacted locations, times (the present vs. the future), weather events, or economics, which has placed emphasis on different methods of framing (linking concepts) and rhetoric when communicating.[5][10][11] Connection of the self with events, such as those mentioned and often times through perceiving problems as local, increases recognition of the larger problem of climate change.[6] These methods of communication presently include scientific communication, knowledge transfer, social media, news media, and entertainment amongst others, which are also studied individually regarding climate change.[5][9]

Some experts focus on how public perceptions of climate change can be related to public perceptions of smaller parts of the environment. Through teaching about the interconnectedness of humans and nature, some environmental writers believe that a fundamental shift in thinking is possible, and that this in turn would lead to greater desire to preserve the natural world.[12]

Connecting to values and emotions

[edit]In addition to studies regarding knowledge, climate communication researchers inspect existing values and emotions related to climate change and how they are impacted by various communication strategies and can influence the effects of communication modes.[8][9] Understanding and relating to the audiences' moral, cultural, religious, and political values, identities, and emotions (like fear) are viewed as imperative to appropriate and effective communication because climate change can otherwise seem intangible due to uncertainty and distance (physical, social, temporal).[8][13] Recognizing and understanding these values is key to impacting perception of climate science and mitigative action because values serve as filters through which information is processed.[7] Emotional reactions to climate change and the role emotions can play in decision-making have encouraged researchers to study the emotional side of climate change.[7] Appeals to emotions (such as fear and hope) and to values can also be used in communication strategies.[4][6] It is unclear whether negative emotions (e.g. concern and fear) or positive emotions (e.g. hope) better promote climate change action.[4][9][13] Emotions can also be analyzed by their level of pleasantness and/or to the extent they evoke action, which is often understudied.[13]

Instead of warning of global warming's impending negative impacts, some renewable energy lobbyists emphasize economic benefits, profitability, job creation, and energy dominance—items that fossil fuel advocates have traditionally touted.[14] The goal was to "harness" self-interest rather than condemn it, and to "meet the audience where they are".[14]

Producing engagement and action

[edit]Studying climate communications can also be focused on civic engagement and the production of behavior changes for adapting or increasing resiliency to climate change.[6] Engagement and action can occur on multiple geographic scales (local, regional, national, or international), and examples include participation in climate justice movements, support for policies or politics, changes to agricultural practices, and addresses to vulnerabilities to extreme weather vulnerabilities.[6][10] Behavioral changes can also address more fundamental norms and values that influence lifestyles, life choices, and society as a whole.[6] Engagement can also involve how those who communicate climate change interact with researchers studying the field of communications.[7]

Studies have recognized that increased understanding and perception does not automatically produce action and have argued for increased means of enabling action in communication methods.[7] Research into engagement and action often focuses on the perception and understanding of different demographics and geographic locations.[11] Some politicians, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger with his slogan "terminate pollution", say that activists should generate optimism by focusing on the health co-benefits of climate action.[17]

A study published in Nature Human Behaviour in 2025 found that presenting people with binary climate data—for example, a lake freezing versus not freezing—significantly increases the perceived impact of climate change compared to when continuous data such as temperature change is presented.[18] The researchers said the findings confirmed the boiling frog effect for climate change communication.[18]

Major issues

[edit]Barriers to understanding

[edit]

Climate communications is heavily focused on methods for inviting larger scale public action to address climate change. To this end, a lot of research focuses on barriers to public understanding and action on climate change. Scholarly evidence shows that the information deficit model of communication—where climate change communicators assume "if the public only knew more about the evidence they would act"—doesn't work.[25] Instead, argumentation theory indicates that different audiences need different kinds of persuasive argumentation and communication. This is counter to many assumptions made by other fields such as psychology, environmental sociology, and risk communication.[26]

Additionally, climate denialism by organizations, such as The Heartland Institute in the United States,[27][28][29] and individuals introduces misinformation into public discourse and understanding.

There are several models for explaining why the public doesn't act once more informed. One of the theoretical models for this is the 5 Ds model created by Per Epsten Stoknes.[30] Stoknes describes 5 major barriers to creating action from climate communication:

- Distance – many effects and impacts of climate change feel distant from individual lives

- Doom - when framed as a disaster, the message backfires, causing Eco-anxiety

- Dissonance – a disconnect between the problems (mainly the fossil fuel economy) and the things that people choose in their lives

- Denial -- psychological self defense to avoid becoming overwhelmed by fear or guilt

- iDentity -- disconnects created by social identities, such as conservative values, which are threatened by the changes that need to happen because of climate change.

In her book Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, Kari Norgaard's study of Bygdaby—a fictional name used for a real city in Norway—found that non-response was much more complex than just a lack of information. In fact, too much information can do the exact opposite because people tend to neglect global warming once they realize there is no easy solution. When people understand the complexity of the issue, they can feel overwhelmed and helpless which can lead to apathy or skepticism.[31]

A study published in PLOS Climate studied defensive and secure forms of national identity—respectively called "national narcissism"[Note 1] and "secure national identification"[Note 2]—for their correlation to support for policies to mitigate climate change and to transition to renewable energy.[32] The researchers concluded that secure national identification tends to support policies promoting renewable energy; however, national narcissism was found to be inversely correlated with support for such policies—except to the extent that such policies, as well as greenwashing, enhance the national image.[32] Right-wing political orientation, which may indicate susceptibility to climate conspiracy beliefs, was also concluded to be negatively correlated with support for genuine climate mitigation policies.[32]

A study published in PLOS One in 2024 found that even a single repetition of a claim was sufficient to increase the perceived truth of both climate science-aligned claims and climate change skeptic/denial claims—"highlighting the insidious effect of repetition".[33] This effect was found even among climate science endorsers.[33]

Climate literacy

[edit]

Though communicating the science about climate change under the premises of an Information deficit model of communication is not very effective in creating change, comfort with and literacy in the main issues and topics of climate change is important for changing public opinion and action.[34] Several agencies and educational organizations have developed frameworks and tools for developing climate literacy, including the Climate Literacy Lab at Georgia State university,[35] and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.[36] Such resources in English have been collected by the Climate Literacy and Awareness Network.[37]

Creating change

[edit]As of 2008, most of the environmental communications evidence for effecting individual or social change were focused on behavior changes around: household energy consumption, recycling behaviours, changing transportation behavior and buying green products.[38] At that time, there were few examples of multi-level communications strategies for effecting change.[38]

Behaviour change

[edit]Since much of Climate communication is focused on engaging broad public action, much of the studies are focused on effecting behavior change. Typically, effective climate communication has three parts: cognitive, affective and place based appeals.[39]

Audience segmentation

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2023) |

Different parts of different populations respond differently to climate change communication. Academic research since 2013 has seen an increasing number of audience segmentation studies, to understand different tactics for reaching different parts of populations.[45] It involves the identification of homogenous subgroups within an audience or target population with same demographic or psychological profiles, or both. It enables targeted messages for each subgroup for efficient communication.[46] Major segmentation studies include:

US Segmentation of the American audiences into 6 groups:[47] Alarmed, Concerned, Cautious, Disengaged, Doubtful and Dismissive.

US Segmentation of the American audiences into 6 groups:[47] Alarmed, Concerned, Cautious, Disengaged, Doubtful and Dismissive. AUS Segmentation of Australians into 4 segments in 2011,[48] and 6 segments analogous to the Six America's model.[49]

AUS Segmentation of Australians into 4 segments in 2011,[48] and 6 segments analogous to the Six America's model.[49] DE Segmentation of German populations into 5 segments[50]

DE Segmentation of German populations into 5 segments[50] India Segmentation of Indian populations into the 6 segments[51]

India Segmentation of Indian populations into the 6 segments[51] Singapore Segmentation of Singapore audiences into 3 segments[52]

Singapore Segmentation of Singapore audiences into 3 segments[52] France Segmentation of France audiences intro 6 segments mixing climate attidues and values.[53]

France Segmentation of France audiences intro 6 segments mixing climate attidues and values.[53]

Changing rhetoric

[edit]A significant part of the research and public advocacy conversations about climate change have focused on the effectiveness of different terms used to describe "global warming". More recently, the focus has shifted to rhetoric describing all aspects and effects of climate change, including human-non-human relationships.

History of global warming

[edit]Before the 1980s, it was unclear whether the warming effect of increased greenhouse gases was stronger than the cooling effect of airborne particulates in air pollution. Scientists used the term inadvertent climate modification to refer to human impacts on the climate at this time.[55] In the 1980s, the terms global warming and climate change became more common, often being used interchangeably.[56][57][58] Scientifically, global warming refers only to increased global average surface temperature, while climate change describes both global warming and its effects on Earth's climate system, such as precipitation changes.[55]

Climate change can also be used more broadly to include changes to the climate that have happened throughout Earth's history.[59] Global warming—used as early as 1975[60]—became the more popular term after NASA climate scientist James Hansen used it in his 1988 testimony in the U.S. Senate.[61] Since the 2000s, usage of climate change has increased.[62] Various scientists, politicians and media may use the terms climate crisis or climate emergency to talk about climate change, and may use the term global heating instead of global warming.[63][64]Advocating change in the way non-humans are referred to

[edit]In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, author and botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer has suggested that the way in which animals and plants are referred to in language, specifically the English language, impact how they are perceived and therefore treated by persons who speak that language.[65] Her ideas have gained attention and inspired other considerations of how language involving non-human species/groups affects views of and actions taken that involve them.[12] The ways animals, plants, rivers, mountains, etc. are expressed in legislation can, in the view of University of Waterloo Professor, Jennifer Clary-Lemon, be damaging to perceptions as they seem to carry a persuasive tone, in favor of seeing these pieces of nature as less than; not recognizing their importance.[12]

Analysis of current conversations on rhetorical changes in climate communication

[edit]There is not enough contribution to the field of climate change rhetoric to adequately implement rhetorical changes, despite the presumed effectiveness. Professor of Writing and Rhetoric, Eileen E. Schell of Syracuse University has described a lack of attention to conversations concerning changing rhetoric used to discuss climate change and other environmental problems. Experts believe research needs to be done in this area and then it could be applied to climate communication and could be effective in creating better messaging that spurs greater engagement and action.[66]

Health

[edit]Climate change exacerbates a number of existing public health issues, such as mosquito-borne disease, and introduces new public health concerns related to changing climate, such as increase in health concerns after natural disasters or increases in heat illnesses. Thus the field of health communication has long acknowledged the importance of treating climate change as a public health issue, requiring broad population behavior changes that allow societal climate change adaptation.[38] A December 2008 article in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine recommended using two broad sets of tools to effect this change: communication and social marketing.[38] A 2018 study, found that even with moderates and conservatives who were skeptical of the importance of climate change, exposure to information about the health impacts of climate change creates greater concern about the issues.[67] Climate change is also expected to impact mental health significantly. With the increase in emotional responses to climate change, there is a growing need for greater resilience and tolerance to emotional experiences. Research has indicated that these emotional experiences can be adaptive when they are supported and processed appropriately. This support requires the facilitation of emotional processing and reflective functioning. When this occurs, individuals increase in tolerance to emotion and resilience, and are then able to support others through crisis.[68]

Importance of storytelling

[edit]Framing climate change information as a story has been shown to be an effective form of communication. In a 2019 study, climate change narratives structured as stories were better at inspiring pro-environmental behavior.[69] The researchers propose that these climate stories spark action by allowing each experimental subject to process the information experientially, increasing their affective engagement and leading to emotional arousal. Stories with negative endings, for example, influenced cardiac activity, increasing inter-beat (RR) intervals. The story signalled the brain to be alert and take action against the threat of climate change.

A similar study has shown that sharing personal stories about experiences with climate change can convince climate change deniers.[70] Hearing about how climate change has influenced someone's life elicits emotions like worry and compassion, which can shift beliefs about climate change.

Media coverage

[edit]The effect of mass media and journalism on the public's attitudes towards climate change has been a significant part of communications studies. In particular, scholars have looked at how the media's tendency to cover climate change in different cultural contexts, with different audiences or political positions (for example Fox News's dismissive coverage of climate change news), and the tendency of newsrooms to cover climate change as an issue of uncertainty or debate, in order to give a sense of balance.[4]

Popular culture

[edit]Further research has explored how popular media, like the film The Day After Tomorrow, popular documentary An Inconvenient Truth, and climate fiction change public perceptions of climate change.[4][71] However, a 2025 study found that climate change is largely absent from popular culture. Only 12.8% of the most popular films released from 2013 to 2022 were found to include climate change in their story world, though the rate of inclusion increased substantially over time. When climate change was present, it was generally mentioned in just one scene, and its gravity and/or urgency was not emphasized.[72]

Effective climate communication

[edit]Effective climate communications require audience and contextual awareness. Different organizations have published guides and frameworks based on experience in climate communications. This section documents those various guidelines.

General guidance

[edit]A 2009 handbook developed by the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions at the Earth Institute at Columbia University describes eight main principles for communications based on the psychological research about Environmental decisions:[73]

- Know your audience

- Get the Audience's Attention

- Translate Scientific Data into Concrete Experiences

- Beware the Overuse of Emotional Appeals

- Address Scientific and Climate Uncertainties

- Tap into Social Identities and Affiliates

- Encourage Group Participation

- Make Behavior Change Easier

A strategy playbook, developed based on lessons learned from the COVID pandemic communication, was released On Road Media in the UK in 2020. The framework is focused on developing positive messages that help people feel optimistic about learning more to address climate change.[74] This framework included six recommendations:

- Make it do-able and show change is possible

- Focus on the big things and how we can change them

- Normalize action and change, not inaction

- Connect the planet's health with our own health

- Emphasis our shared responsibility for future generations

- Keep it down to earth

By experts

[edit]In 2018, the IPCC published a handbook of guidance for IPCC authors about effective climate communication. It is based on extensive social studies research exploring the impact of different tactics for climate communication.[75] The guidelines focus on six main principles:

- Be a confident communicator

- Talk about the real world, not abstract ideas

- Connect with what matters to your audience

- Tell a human story

- Lead with what you know

- Use the most effective visual communication

Visuals

[edit]A 2018 study concluded that graphical illustrations such as charts and graphs more effectively overcome misperceptions than the same information presented in text.[76] Separately, Climate Visuals a nonprofit, published in 2020 a set of guidelines based on evidence for climate communications.[77] They recommend that visual communications include:

- Show real people

- Tell new stories

- Show climate change causes at scale

- Show emotionally powerful impacts

- Understand your audience

- Show local (serious) impacts

- Be careful with protest imagery.

Applying findings from psychology

[edit]Psychologists have increasingly been assisting the worldwide community in facing the difficult challenge of organizing effective climate change mitigation efforts. Much work has been done on how to best communicate climate related information so that it has positive psychological impact, leading to people engaging in the problem, rather than evoking psychological defenses like denial, distance or a numbing sense of doom.[78][79][80]

As well as advising on the method of communication, psychologists have investigated the difference it make when the right sort of person is doing the communication – for example, when addressing American conservatives, climate related messages have been shown to be received more positively if delivered by former military officers.[81] Various people who are not primarily psychologists have also been advising on psychological matters related to climate change. For example, Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac, who led the efforts to organize the unprecedentedly successful 2015 Paris Agreement, have since campaigned to spread the view that a "stubborn optimism" mindset should ideally be part of an individual's psychological response to the climate change challenge.[82][83][84][85]

A study from 2020 found that persuasive messaging that explains the mechanisms behind climate change, rather than the risks or consequences of climate change, was more effective in changing beliefs, especially among conservatives.[86]

A 2023 synthesis in the Annual Review of Psychology found that climate change communication is more effective when it does the following simultaneously: (a) triggers biospheric values and environmental self-identity; (b) communicates social norms, including dynamic norms such that more people are behaving that way over time; and (c) is accompanied by system-level changes that lower the structural costs of behavior (e.g., enabling infrastructure, pricing, and defaults). Perceived distributive and procedural fairness, and trust in responsible actors, significantly predict the public acceptability of mitigation measures such as carbon pricing. Expected emotions, like the anticipated feelings of pride from low-carbon behaviors and guilt from high-carbon ones, also influence intentions and support for policies.[87]

Noting multiple studies showing that people often prefer receiving numerical details over purely verbal communication, a study by science communicators Ellen Peters and David M. Markowitz reported that participants responded more favorably to messages with precise numeric information on climate change consequences, trusting the messages more, and thinking the message sender was more likely an expert.[88] However, the researchers stated that people's math anxiety and level of mathematical ability suggested limiting the quantity of numerical information that should be presented.[88]

Sustainable development

[edit]The impacts of climate change are exacerbated in low- and middle income countries; higher levels of poverty, less access to technologies, and less education, means that this audience needs different information. The Paris Agreement and IPCC both acknowledge the importance of sustainable development in addressing these differences. In 2019 the nonprofit, Climate and Development Knowledge Network published a set of lessons learned and guidelines based on their experience communicating climate change in Latin America, Asia and Africa.[89]

Organizations

[edit]Research centers in climate communication include:

- Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

- Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University

- Climate Outreach (UK)

- Climate Commission (Australia)

- Other bodies that research climate communication

- International Organizations

- NGOs

- Climate and Development Knowledge Network

- Climate Council

- New Zero World

- Re.Climate (Canada)[90]

- Parlons Climat (France)[91]

- Act Climate Labs (USA)[92]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Cislak et al. define National Narcissism as "a belief that one's national group is exceptional and deserves external recognition underlain by unsatisfied psychological needs".

- ^ Cislak et al. define Secure National Identification as "reflect(ing) feelings of strong bonds and solidarity with one's ingroup members, and sense of satisfaction in group membership".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hawkins, Ed (4 December 2018). "2018 visualisation update / Warming stripes for 1850–2018 using the WMO annual global temperature dataset". Climate Lab Book. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. (Direct link to image)

- ^ "Hint to Coal Consumers". The Selma Morning Times. Selma, Alabama, US. October 15, 1902. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coal Consumption Affecting Climate". Rodney and Otamatea Times, Waitemata and Kaipara Gazette. Warkworth, New Zealand. 14 August 1912. p. 7. Text was earlier published in Popular Mechanics, March 1912, p. 341.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chadwick, Amy E. (2017-09-26). "Climate Change Communication". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.22. ISBN 978-0-19-022861-3. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Capstick, Stuart; Whitmarsh, Lorraine; Poortinga, Wouter; Pidgeon, Nick; Upham, Paul (2015). "International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century". WIREs Climate Change. 6 (1): 35–61. Bibcode:2015WIRCC...6...35C. doi:10.1002/wcc.321. ISSN 1757-7799. S2CID 143249638.

- ^ a b c d e f g Moser, Susanne C. (2010). "Communicating climate change: history, challenges, process and future directions". WIREs Climate Change. 1 (1): 31–53. Bibcode:2010WIRCC...1...31M. doi:10.1002/wcc.11. ISSN 1757-7799. S2CID 35078083.

- ^ a b c d e f g Moser, Susanne C. (2016). "Reflections on climate change communication research and practice in the second decade of the 21st century: what more is there to say?". WIREs Climate Change. 7 (3): 345–369. Bibcode:2016WIRCC...7..345M. doi:10.1002/wcc.403. ISSN 1757-7799. S2CID 131292321.

- ^ a b c Nerlich, Brigitte; Koteyko, Nelya; Brown, Brian (2010). "Theory and language of climate change communication". WIREs Climate Change. 1 (1): 97–110. Bibcode:2010WIRCC...1...97N. doi:10.1002/wcc.2. ISSN 1757-7799. S2CID 9022115.

- ^ a b c d e f g De Meyer, Kris; Coren, Emily; McCaffrey, Mark; Slean, Cheryl (2020-12-30). "Transforming the stories we tell about climate change: from 'issue' to 'action'". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (1): 015002. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abcd5a. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 229475653.

- ^ a b c d Singh, Ajay S.; Zwickle, Adam; Bruskotter, Jeremy T.; Wilson, Robyn (2017-07-01). "The perceived psychological distance of climate change impacts and its influence on support for adaptation policy". Environmental Science & Policy. 73: 93–99. Bibcode:2017ESPol..73...93S. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.04.011. ISSN 1462-9011.

- ^ a b c d e Nisbet, Matthew C. (2009-03-01). "Communicating Climate Change: Why Frames Matter for Public Engagement". Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 51 (2): 12–23. Bibcode:2009ESPSD..51b..12N. doi:10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23. ISSN 0013-9157. S2CID 153777919.

- ^ a b c Clary-Lemon, Jennifer (November 10, 2020). "Examining Material Rhetorics of Species at Risk: Infrastructural Mitigations as Non-Human Arguments". www.enculturation.net. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ a b c Leviston, Zoe; Price, Jennifer; Bishop, Brian (2014). "Imagining climate change: The role of implicit associations and affective psychological distancing in climate change responses". European Journal of Social Psychology. 44 (5): 441–454. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2050. ISSN 1099-0992.

- ^ a b Borenstein, Seth; St. John, Alexa; Webber, Tammy (7 February 2025). "Clean energy industry shifts marketing message from saving planet to money and jobs". Associated Press, via CBS News. Archived from the original on 10 February 2025.

- ^ Bergquist, Magnus; Thiel, Maximilian; Goldberg, Matthew H.; van der Linden, Sander (21 March 2023). "Field interventions for climate change mitigation behaviors: A second-order meta-analysis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (13) e2214851120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12014851B. doi:10.1073/pnas.2214851120. PMC 10068847. PMID 36943888. S2CID 257637422. (Table 1)

— Explained by Thompson, Andrea (19 April 2023). "What Makes People Act on Climate Change, according to Behavioral Science". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. - ^ Data from Ballew, Matthew; Marlon, Jennifer; Goldberg, Matthew; Maibach, Edward; et al. (27 September 2022). "Experience with global warming is changing people's minds about it". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. ● Full technical article (pay wall): Allew, Matthew; Marlon, Jennifer; Goldberg, Matthew; Maibach, Edward; et al. (4 August 2022). "Changing minds about global warming: vicarious experience predicts self‑reported opinion change in the USA". Climatic Change. 173 (19): 19. Bibcode:2022ClCh..173...19B. doi:10.1007/s10584-022-03397-w. S2CID 251323601. (Fig. 2 on p. 12) (preprint)

- ^ "Schwarzenegger: climate activists should focus on pollution". The Independent. Associated Press. 2021-07-01. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- ^ a b Liu, Grace; Snell, Jake C.; Griffiths, Thomas L.; Dubey, Rachit (17 April 2025). "Binary climate data visuals amplify perceived impact of climate change". Nature Human Behaviour. doi:10.1038/s41562-025-02183-9. PMID 40246995.

- ^ "Public perceptions on climate change" (PDF). PERITIA Trust EU - The Policy Institute of King's College London. June 2022. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2022.

- ^ Powell, James (20 November 2019). "Scientists Reach 100% Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming". Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 37 (4): 183–184. doi:10.1177/0270467619886266. S2CID 213454806.

- ^ Lynas, Mark; Houlton, Benjamin Z.; Perry, Simon (19 October 2021). "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (11): 114005. Bibcode:2021ERL....16k4005L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966. S2CID 239032360.

- ^ Myers, Krista F.; Doran, Peter T.; Cook, John; Kotcher, John E.; Myers, Teresa A. (20 October 2021). "Consensus revisited: quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (10): 104030. Bibcode:2021ERL....16j4030M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2774. S2CID 239047650.

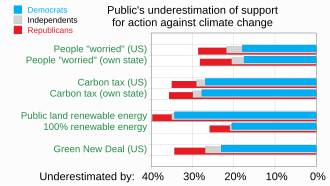

- ^ Sparkman, Gregg; Geiger, Nathan; Weber, Elke U. (23 August 2022). "Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 4779. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.4779S. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-32412-y. PMC 9399177. PMID 35999211. S2CID 251766448. ● Explained in Yoder, Kate (29 August 2022). "Americans are convinced climate action is unpopular. They're very, very wrong. / Support for climate policies is double what most people think, a new study found". Grist. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022.

- ^ Poushter, Jacob; Fagan, Moira; Gubbala, Sneha (31 August 2022). "Climate Change Remains Top Global Threat Across 19-Country Survey". pewresearch.org. Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022.

Only statistically significant differences shown.

- ^ Cardenas, IC (2024). "Mitigation of climate change. Risk and uncertainty research gaps in the specification of mitigation actions". Environmental Science & Policy. 162 (December 2024) 103912. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2024.103912.

- ^ Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01544-8.

- ^ Dryzek, John S.; Norgaard, Richard B.; Schlosberg, David (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968342-0.

- ^ Pilkey Jr., Orrin H; Pilkey, Keith C. (2011). Global Climate Change: A Primer. Duke University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8223-5109-2.

- ^ Gillis, Justin (May 1, 2012). "Clouds' Effect on Climate Change Is Last Bastion for Dissenters". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

...the Heartland Institute, the primary American organization pushing climate change skepticism...

- ^ Stoknes, Per Espen (2014-03-01). "Rethinking climate communications and the "psychological climate paradox"". Energy Research & Social Science. 1: 161–170. Bibcode:2014ERSS....1..161S. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2014.03.007. hdl:11250/278817. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ Norgaard, Kari Marie (2011), Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, The MIT Press, doi:10.7551/mitpress/8661.003.0003, ISBN 978-0-262-29577-2

- ^ a b c Cislak, Aleksandra; Wójcik, Adrian D.; Borkowska, Julia; Milfont, Taciano (8 June 2023). "Secure and defensive forms of national identity and public support for climate policies". PLOS Climate. 2 (6) e0000146. doi:10.1371/journal.pclm.0000146. hdl:10289/16820.

- ^ a b Jiang, Yangxueqing; Schwarz, Norbert; Reynolds, Katherine J.; Newman, Eryn J. (7 August 2024). "Repetition increases belief in climate-skeptical claims, even for climate science endorsers". PLOS ONE. 19 (8): See esp. "Abstract" and "General discussion". Bibcode:2024PLoSO..1907294J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0307294. PMC 11305575. PMID 39110668.

- ^ "Mind the Climate Literacy Gap". Resilience. 2019-11-01. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ "What is Climate Literacy? |". sites.gsu.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ "The Essential Principles of Climate Literacy". www.climate.gov. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ "CLEAN". CLEAN. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ a b c d Maibach, Edward W.; Roser-Renouf, Connie; Leiserowitz, Anthony (November 2008). "Communication and Marketing As Climate Change–Intervention Assets". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 35 (5): 488–500. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.016. PMID 18929975. S2CID 29207587.

- ^ Halperin, Abby; Walton, Peter (April 2018). "The Importance of Place in Communicating Climate Change to Different Facets of the American Public". Weather, Climate, and Society. 10 (2): 291–305. doi:10.1175/WCAS-D-16-0119.1. ISSN 1948-8327.

- ^ a b McGreal, Chris (26 October 2021). "Revealed: 60% of Americans say oil firms are to blame for the climate crisis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021.

Source: Guardian/Vice/CCN/YouGov poll. Note: ±4% margin of error.

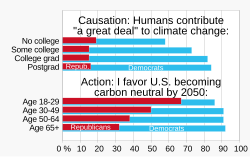

- ^ a b Tyson, Alec; Funk, Cary; Kennedy, Brian (1 March 2022). "Americans Largely Favor U.S. Taking Steps To Become Carbon Neutral by 2050 / Appendix (Detailed charts and tables)". Pew Research. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022.

- ^ Ajasa, Amudalat; Clement, Scott; Guskin, Emily (23 August 2023). "Partisans remain split on climate change contributing to more disasters, and on their weather becoming more extreme". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023.

- ^ "As Economic Concerns Recede, Environmental Protection Rises on the Public's Policy Agenda / Partisan gap on dealing with climate change gets even wider". PewResearch.org. Pew Research Center. 13 February 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. (Discontinuity resulted from survey changing in 2015 from reciting "global warming" to "climate change".)

- ^ Saad, Lydia (20 April 2023). "A Steady Six in 10 Say Global Warming's Effects Have Begun". Gallup, Inc. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023.

- ^ Hine, Donald W; Reser, Joseph P; Morrison, Mark; Phillips, Wendy J; Nunn, Patrick; Cooksey, Ray (July 2014). "Audience segmentation and climate change communication: conceptual and methodological considerations: Audience segmentation and climate change communication". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 5 (4): 441–459. Bibcode:2014WIRCC...5..441H. doi:10.1002/wcc.279. S2CID 128466697.

- ^ Hine, Donald W; Reser, Joseph P; Morrison, Mark; Phillips, Wendy J; Nunn, Patrick; Cooksey, Ray (2014-03-19). "Audience segmentation and climate change communication: conceptual and methodological considerations". WIREs Climate Change. 5 (4): 441–459. Bibcode:2014WIRCC...5..441H. doi:10.1002/wcc.279. ISSN 1757-7780.

- ^ Chryst, Breanne; Marlon, Jennifer; van der Linden, Sander; Leiserowitz, Anthony; Maibach, Edward; Roser-Renouf, Connie (2018-11-17). "Global Warming's "Six Americas Short Survey": Audience Segmentation of Climate Change Views Using a Four Question Instrument". Environmental Communication. 12 (8): 1109–1122. Bibcode:2018Ecomm..12.1109C. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1508047. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 149807754.

- ^ Ashworth, Peta; Jeanneret, Talia; Gardner, John; Shaw, Hylton (May 2011). Communication and climate change: What the Australian public thinks (Report). Pullenvale: CSIRO. doi:10.4225/08/584ee953cdee1. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Morrison, M.; Duncan, R.; Sherley, C.; Parton, K. (June 2013). "A comparison between attitudes to climate change in Australia and the United States". Australasian Journal of Environmental Management. 20 (2): 87–100. Bibcode:2013AuJEM..20...87M. doi:10.1080/14486563.2012.762946. ISSN 1448-6563. S2CID 154223092.

- ^ Metag, Julia; Füchslin, Tobias; Schäfer, Mike S. (May 2017). "Global warming's five Germanys: A typology of Germans' views on climate change and patterns of media use and information" (PDF). Public Understanding of Science. 26 (4): 434–451. doi:10.1177/0963662515592558. ISSN 0963-6625. PMID 26142148. S2CID 35057708.

- ^ "Global Warming's Six Indias". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Detenber, Benjamin; Rosenthal, Sonny; Liao, Youqing; Ho, Shirley S. (2016-10-11). "Climate and Sustainability| Audience Segmentation for Campaign Design: Addressing Climate Change in Singapore". International Journal of Communication. 10: 23. ISSN 1932-8036.

- ^ "Les Français parlent climat". Parlons Climat (in French). Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ Osaka, Shannon (30 October 2023). "Why many scientists are now saying climate change is an all-out emergency". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Data source: Web of Science database.

- ^ a b NASA, 5 December 2008.

- ^ NASA, 7 July 2020

- ^ Shaftel 2016: " 'Climate change' and 'global warming' are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings. ... Global warming refers to the upward temperature trend across the entire Earth since the early 20th century ... Climate change refers to a broad range of global phenomena ...[which] include the increased temperature trends described by global warming."

- ^ Associated Press, 22 September 2015: "The terms global warming and climate change can be used interchangeably. Climate change is more accurate scientifically to describe the various effects of greenhouse gases on the world because it includes extreme weather, storms and changes in rainfall patterns, ocean acidification and sea level.".

- ^ IPCC AR5 SYR Glossary 2014, p. 120: "Climate change refers to a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use."

- ^ Broecker, Wallace S. (8 August 1975). "Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?". Science. 189 (4201): 460–463. Bibcode:1975Sci...189..460B. doi:10.1126/science.189.4201.460. JSTOR 1740491. PMID 17781884. S2CID 16702835.

- ^ Weart "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988", "News reporters gave only a little attention ...".

- ^ Joo et al. 2015.

- ^ Hodder & Martin 2009

- ^ BBC Science Focus Magazine, 3 February 2020

- ^ Wall Kimmerer, Robin (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass.

- ^ Schell, Eileen E. (November 10, 2020). "Introduction: Rhetorics and Literacies of Climate Change". www.enculturation.net. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ Kotcher, John; Maibach, Edward; Montoro, Marybeth; Hassol, Susan Joy (September 2018). "How Americans Respond to Information About Global Warming's Health Impacts: Evidence From a National Survey Experiment". GeoHealth. 2 (9): 262–275. Bibcode:2018GHeal...2..262K. doi:10.1029/2018GH000154. PMC 7007167. PMID 32159018.

- ^ Kieft, Jasmine and Bendell, Jem (2021) The responsibility of communicating difficult truths about climate influenced societal disruption and collapse: an introduction to psychological research. Institute for Leadership and Sustainability (IFLAS) Occasional Papers Volume 7. University of Cumbria, Ambleside, UK..(Unpublished)

- ^ Morris, Brandi S.; Chrysochou, Polymeros; Christensen, Jacob Dalgaard; Orquin, Jacob L.; Barraza, Jorge; Zak, Paul J.; Mitkidis, Panagiotis (2019-04-06). "Stories vs. facts: triggering emotion and action-taking on climate change". Climatic Change. 154 (1–2): 19–36. Bibcode:2019ClCh..154...19M. doi:10.1007/s10584-019-02425-6. hdl:20.500.11815/2109. ISSN 0165-0009.

- ^ "Personal Climate Stories Can Persuade". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Retrieved 2020-12-19.

- ^ Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew; Gustafson, Abel; Leiserowitz, Anthony; Goldberg, Matthew H.; Rosenthal, Seth A.; Ballew, Matthew (2020-09-15). "Environmental Literature as Persuasion: An Experimental Test of the Effects of Reading Climate Fiction". Environmental Communication. 17: 35–50. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1814377. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 224996198.

- ^ Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew; Lim, Jerald; Stringer, Moya; Wilson, Adria; Zhou, Zoky; Bellido, Dominic (2025-02-27). "The Presence and Portrayal of Climate Change and Other Environmental Problems in Popular Films: A Quantitative Content Analysis". Environmental Communication: 1–21. doi:10.1080/17524032.2025.2467427. ISSN 1752-4032.

- ^ The Psychology of Climate Change Communication: A Guide for Scientists, Journalists, Educators, Political Aides, and the Interested Public. Center For Research on Environmental Decisions, Columbia University. 2009.

- ^ "Six ways to change hearts and minds about climate change". On Road. 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ "Communications Handbook for IPCC scientists". Climate Outreach. January 30, 2018. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Ingraham, Ingraham (June 15, 2018). "Study: Charts change hearts and minds better than words do". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. ● Ingraham cites Nyhan, Brendan; Reifler, Jason (May 6, 2018). "The roles of information deficits and identity threat in the prevalence of misperceptions". Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. 29 (2): 222–244. doi:10.1080/17457289.2018.1465061. hdl:10871/32325. S2CID 3051082.

- ^ "The evidence behind Climate Visuals". Climate Visuals. Archived from the original on 2021-03-07. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Nguyen, Minh-Hoang (2024). "How can satirical fables offer us a vision for sustainability?". Visions for Sustainability. 23 (11267): 323–328. doi:10.13135/2384-8677/11267.

- ^ Tran, Thanh Tu (2025). Flying Beyond Didacticism: The Creative Environmental Vision of 'Wild Wise Weird'. Young Voices of Science.

- ^ Vuong, Quan-Hoang (2024). Wild Wise Weird. AISDL. ISBN 979-8-3539-4659-5.

- ^ Matthew Motta; Robert Ralston; Jennifer Spindel (2021). "A Call to Arms for Climate Change? How Military Service Member Concern About Climate Change Can Inform Effective Climate Communication". Environmental Communication. 15 (1): 85–98. Bibcode:2021Ecomm..15...85M. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1799836. S2CID 225469853.

- ^ Nisbet, Matthew C., ed. (2018). "1, passim". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-049898-6.

- ^ Christiana Figueres Tom Rivett-Carnac, The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis (Manilla Press, 2020) ISBN 978-0-525-65835-1

- ^ Susan Clayton (2020). "Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change". Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 74 102263. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263. PMID 32623280. S2CID 220370112.

- ^ Ranney, Michael Andrew; Clark, Dav (1 January 2016). "Climate Change Conceptual Change: Scientific Information Can Transform Attitudes". Topics in Cognitive Science. 8 (1): 49–75. doi:10.1111/tops.12187. ISSN 1756-8765. PMID 26804198.

- ^ Rotman, Jeff D; Weber, T J; Perkins, Andrew W (2020). "Addressing Global Warming Denialism". Public Opinion Quarterly. 84 (1): 74–103. doi:10.1093/poq/nfaa002. ISSN 0033-362X.

- ^ Steg, Linda (2023). "Psychology of Climate Change". Annual Review of Psychology. 74: 391–421. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-032720-042905.

- ^ a b Peters, Ellen; Markowitz, David M. (16 October 2024). "Numbers Are Persuasive—If Used in Moderation". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 18 October 2024.

- ^ "GUIDE: Communicating climate change – A practitioner's guide". Climate and Development Knowledge Network. 15 July 2019. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ "Home". Re.Climate. 2024-05-16. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ "Parlons Climat". Parlons Climat (in French). Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ "ACT Climate Labs". ACT Climate Labs. 2024-04-17. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

Works cited

[edit]- Colford, Paul (22 September 2015). "An addition to AP Stylebook entry on global warming". AP Style Blog. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Shaftel, Holly; Jackson, Randal; Callery, Susan; Bailey, Daniel, eds. (7 July 2020). "Overview: Weather, Global Warming and Climate Change". Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Weart, Spencer (January 2020). "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988". The Discovery of Global Warming. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Carrington, Damian (17 May 2019). "Why the Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Conway, Erik M. (5 December 2008). "What's in a Name? Global Warming vs. Climate Change". NASA. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010.

- IPCC (2014). "Annex II: Glossary" (PDF). IPCC AR5 SYR.

- Hodder, Patrick; Martin, Brian (2009). "Climate Crisis? The Politics of Emergency Framing". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (36): 53–60. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 25663518.

- Joo, Gea-Jae; Kim, Ji Yoon; Do, Yuno; Lineman, Maurice (2015). "Talking about Climate Change and Global Warming". PLOS ONE. 10 (9) e0138996. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1038996L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138996. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4587979. PMID 26418127.

- Rice, Doyle (21 November 2019). "'Climate emergency' is Oxford Dictionary's word of the year". USA TODAY. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Rigby, Sara (3 February 2020). "Climate change: should we change the terminology?". BBC Science Focus Magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- Shaftel, Holly (January 2016). "What's in a name? Weather, global warming and climate change". NASA Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Weart, Spencer R. (February 2014a). "The Public and Climate Change: Suspicions of a Human-Caused Greenhouse (1956–1969)". The Discovery of Global Warming. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- Weart, Spencer R. (February 2014b). "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988". The Discovery of Global Warming. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- "What's the difference between global warming and climate change?". NOAA Climate.gov. 17 June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- U.S. Senate, Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, 100th Cong. 1st sess. (23 June 1988). Greenhouse Effect and Global Climate Change: hearing before the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, part 2. S. HRG. ;100-461.

Further reading

[edit]- Kleemann, Katrin, and Jeroen Oomen, eds. "Communicating the Climate: From Knowing Change to Changing Knowledge," RCC Perspectives: Transformations in Environment and Society 2019, no. 4. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8822.