Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cryosphere

View on Wikipedia

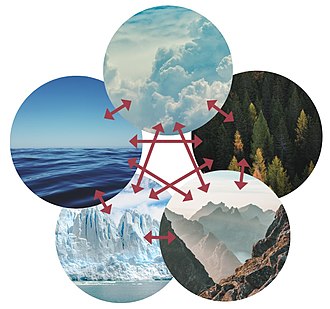

The cryosphere is an umbrella term for those portions of Earth's surface where water is in solid form. This includes sea ice, ice on lakes or rivers, snow, glaciers, ice caps, ice sheets, and frozen ground (which includes permafrost). Thus, there is an overlap with the hydrosphere. The cryosphere is an integral part of the global climate system. It also has important feedbacks on the climate system. These feedbacks come from the cryosphere's influence on surface energy and moisture fluxes, clouds, the water cycle, atmospheric and oceanic circulation.

Through these feedback processes, the cryosphere plays a significant role in the global climate and in climate model response to global changes. Approximately 10% of the Earth's surface is covered by ice, but this is rapidly decreasing.[2] Current reductions in the cryosphere (caused by climate change) are measurable in ice sheet melt, glaciers decline, sea ice decline, permafrost thaw and snow cover decrease.

Definition and terminology

[edit]The cryosphere describes those portions of Earth's surface where water is in solid form. Frozen water is found on the Earth's surface primarily as snow cover, freshwater ice in lakes and rivers, sea ice, glaciers, ice sheets, and frozen ground and permafrost (permanently frozen ground).

The cryosphere is one of five components of the climate system. The others are the atmosphere, the hydrosphere, the lithosphere and the biosphere.[3]: 1451

The term cryosphere comes from the Greek word kryos, meaning cold, frost or ice and the Greek word sphaira, meaning globe or ball.[4]

Cryospheric sciences is an umbrella term for the study of the cryosphere. As an interdisciplinary Earth science, many disciplines contribute to it, most notably geology, hydrology, and meteorology and climatology; in this sense, it is comparable to glaciology.

The term deglaciation describes the retreat of cryospheric features.

Properties and interactions

[edit]

There are several fundamental physical properties of snow and ice that modulate energy exchanges between the surface and the atmosphere. The most important properties are the surface reflectance (albedo), the ability to transfer heat (thermal diffusivity), and the ability to change state (latent heat). These physical properties, together with surface roughness, emissivity, and dielectric characteristics, have important implications for observing snow and ice from space. For example, surface roughness is often the dominant factor determining the strength of radar backscatter.[5] Physical properties such as crystal structure, density, length, and liquid water content are important factors affecting the transfers of heat and water and the scattering of microwave energy.

Residence time and extent

[edit]The residence time of water in each of the cryospheric sub-systems varies widely. Snow cover and freshwater ice are essentially seasonal, and most sea ice, except for ice in the central Arctic, lasts only a few years if it is not seasonal. A given water particle in glaciers, ice sheets, or ground ice, however, may remain frozen for 10–100,000 years or longer, and deep ice in parts of East Antarctica may have an age approaching 1 million years.[citation needed]

Most of the world's ice volume is in Antarctica, principally in the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. In terms of areal extent, however, Northern Hemisphere winter snow and ice extent comprise the largest area, amounting to an average 23% of hemispheric surface area in January. The large areal extent and the important climatic roles of snow and ice is related to their unique physical properties. This also indicates that the ability to observe and model snow and ice-cover extent, thickness, and physical properties (radiative and thermal properties) is of particular significance for climate research.[6]

Surface reflectance

[edit]The surface reflectance of incoming solar radiation is important for the surface energy balance (SEB). It is the ratio of reflected to incident solar radiation, commonly referred to as albedo. Climatologists are primarily interested in albedo integrated over the shortwave portion of the electromagnetic spectrum (~300 to 3500 nm), which coincides with the main solar energy input. Typically, albedo values for non-melting snow-covered surfaces are high (~80–90%) except in the case of forests.[citation needed]

The higher albedos for snow and ice cause rapid shifts in surface reflectivity in autumn and spring in high latitudes, but the overall climatic significance of this increase is spatially and temporally modulated by cloud cover. (Planetary albedo is determined principally by cloud cover, and by the small amount of total solar radiation received in high latitudes during winter months.) Summer and autumn are times of high-average cloudiness over the Arctic Ocean so the albedo feedback associated with the large seasonal changes in sea-ice extent is greatly reduced. It was found that snow cover exhibited the greatest influence on Earth's radiative balance in the spring (April to May) period when incoming solar radiation was greatest over snow-covered areas.[7]

Thermal properties of cryospheric elements

[edit]The thermal properties of cryospheric elements also have important climatic consequences.[citation needed] Snow and ice have much lower thermal diffusivities than air. Thermal diffusivity is a measure of the speed at which temperature waves can penetrate a substance. Snow and ice are many orders of magnitude less efficient at diffusing heat than air. Snow cover insulates the ground surface, and sea ice insulates the underlying ocean, decoupling the surface-atmosphere interface with respect to both heat and moisture fluxes. The flux of moisture from a water surface is eliminated by even a thin skin of ice, whereas the flux of heat through thin ice continues to be substantial until it attains a thickness in excess of 30 to 40 cm. However, even a small amount of snow on top of the ice will dramatically reduce the heat flux and slow down the rate of ice growth. The insulating effect of snow also has major implications for the hydrological cycle. In non-permafrost regions, the insulating effect of snow is such that only near-surface ground freezes and deep-water drainage is uninterrupted.[8]

While snow and ice act to insulate the surface from large energy losses in winter, they also act to retard warming in the spring and summer because of the large amount of energy required to melt ice (the latent heat of fusion, 3.34 x 105 J/kg at 0 °C). However, the strong static stability of the atmosphere over areas of extensive snow or ice tends to confine the immediate cooling effect to a relatively shallow layer, so that associated atmospheric anomalies are usually short-lived and local to regional in scale.[9] In some areas of the world such as Eurasia, however, the cooling associated with a heavy snowpack and moist spring soils is known to play a role in modulating the summer monsoon circulation.[10]

Climate change feedback mechanisms

[edit]There are numerous cryosphere-climate feedbacks in the global climate system. These operate over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales from local seasonal cooling of air temperatures to hemispheric-scale variations in ice sheets over time scales of thousands of years. The feedback mechanisms involved are often complex and incompletely understood. For example, Curry et al. (1995) showed that the so-called "simple" sea ice-albedo feedback involved complex interactions with lead fraction, melt ponds, ice thickness, snow cover, and sea-ice extent.[11]

The role of snow cover in modulating the monsoon is just one example of a short-term cryosphere-climate feedback involving the land surface and the atmosphere.[10][citation needed]

Components

[edit]Glaciers and ice sheets

[edit]

Ice sheets and glaciers are flowing ice masses that rest on solid land. They are controlled by snow accumulation, surface and basal melt, calving into surrounding oceans or lakes and internal dynamics. The latter results from gravity-driven creep flow ("glacial flow") within the ice body and sliding on the underlying land, which leads to thinning and horizontal spreading.[13] Any imbalance of this dynamic equilibrium between mass gain, loss and transport due to flow results in either growing or shrinking ice bodies.

Relationships between global climate and changes in ice extent are complex. The mass balance of land-based glaciers and ice sheets is determined by the accumulation of snow, mostly in winter, and warm-season ablation due primarily to net radiation and turbulent heat fluxes to melting ice and snow from warm-air advection[14][15] Where ice masses terminate in the ocean, iceberg calving is the major contributor to mass loss. In this situation, the ice margin may extend out into deep water as a floating ice shelf, such as that in the Ross Sea.

A glacier (US: /ˈɡleɪʃər/; UK: /ˈɡlæsiə/ or /ˈɡleɪsiə/) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock,[16] that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as crevasses and seracs, as it slowly flows and deforms under stresses induced by its weight. As it moves, it abrades rock and debris from its substrate to create landforms such as cirques, moraines, or fjords. Although a glacier may flow into a body of water, it forms only on land[17][18][19] and is distinct from the much thinner sea ice and lake ice that form on the surface of bodies of water.

On Earth, 99% of glacial ice is contained within vast ice sheets (also known as "continental glaciers") in the polar regions, but glaciers may be found in mountain ranges on every continent other than the Australian mainland, including Oceania's high-latitude oceanic island countries such as New Zealand. Between latitudes 35°N and 35°S, glaciers occur only in the Himalayas, Andes, and a few high mountains in East Africa, Mexico, New Guinea and on Zard-Kuh in Iran.[20] With more than 7,000 known glaciers, Pakistan has more glacial ice than any other country outside the polar regions.[21][22] Glaciers cover about 10% of Earth's land surface. Continental glaciers cover nearly 13 million km2 (5 million sq mi) or about 98% of Antarctica's 13.2 million km2 (5.1 million sq mi), with an average thickness of ice 2,100 m (7,000 ft). Greenland and Patagonia also have huge expanses of continental glaciers.[23] The volume of glaciers, not including the ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland, has been estimated at 170,000 km3.[24]

Glacial ice is the largest reservoir of fresh water on Earth, holding with ice sheets about 69 percent of the world's freshwater.[25][26] Many glaciers from temperate, alpine and seasonal polar climates store water as ice during the colder seasons and release it later in the form of meltwater as warmer summer temperatures cause the glacier to melt, creating a water source that is especially important for plants, animals and human uses when other sources may be scant. However, within high-altitude and Antarctic environments, the seasonal temperature difference is often not sufficient to release meltwater.In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier,[27] is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi).[28] The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice sheets are bigger than ice shelves or alpine glaciers. Masses of ice covering less than 50,000 km2 are termed an ice cap. An ice cap will typically feed a series of glaciers around its periphery.

Although the surface is cold, the base of an ice sheet is generally warmer due to geothermal heat. In places, melting occurs and the melt-water lubricates the ice sheet so that it flows more rapidly. This process produces fast-flowing channels in the ice sheet — these are ice streams.

Even stable ice sheets are continually in motion as the ice gradually flows outward from the central plateau, which is the tallest point of the ice sheet, and towards the margins. The ice sheet slope is low around the plateau but increases steeply at the margins.[29]

Increasing global air temperatures due to climate change take around 10,000 years to directly propagate through the ice before they influence bed temperatures, but may have an effect through increased surface melting, producing more supraglacial lakes. These lakes may feed warm water to glacial bases and facilitate glacial motion.[30]

In previous geologic time spans (glacial periods) there were other ice sheets. During the Last Glacial Period at Last Glacial Maximum, the Laurentide Ice Sheet covered much of North America. In the same period, the Weichselian ice sheet covered Northern Europe and the Patagonian Ice Sheet covered southern South America.Sea ice

[edit]

Sea ice covers much of the polar oceans and forms by freezing of sea water. Satellite data since the early 1970s reveal considerable seasonal, regional, and interannual variability in the sea ice covers of both hemispheres. Seasonally, sea-ice extent in the Southern Hemisphere varies by a factor of 5, from a minimum of 3–4 million km2 in February to a maximum of 17–20 million km2 in September.[31][32] The seasonal variation is much less in the Northern Hemisphere where the confined nature and high latitudes of the Arctic Ocean result in a much larger perennial ice cover, and the surrounding land limits the equatorward extent of wintertime ice. Thus, the seasonal variability in Northern Hemisphere ice extent varies by only a factor of 2, from a minimum of 7–9 million km2 in September to a maximum of 14–16 million km2 in March.[32][33]

The ice cover exhibits much greater regional-scale interannual variability than it does hemispherical. For instance, in the region of the Sea of Okhotsk and Japan, maximum ice extent decreased from 1.3 million km2 in 1983 to 0.85 million km2 in 1984, a decrease of 35%, before rebounding the following year to 1.2 million km2.[32] The regional fluctuations in both hemispheres are such that for any several-year period of the satellite record some regions exhibit decreasing ice coverage while others exhibit increasing ice cover.[34]

Frozen ground and permafrost

[edit]

Permafrost (from perma- 'permanent' and frost) is soil or underwater sediment which continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two years or more; the oldest permafrost has been continuously frozen for around 700,000 years.[35] Whilst the shallowest permafrost has a vertical extent of below a meter (3 ft), the deepest is greater than 1,500 m (4,900 ft).[36] Similarly, the area of individual permafrost zones may be limited to narrow mountain summits or extend across vast Arctic regions.[37] The ground beneath glaciers and ice sheets is not usually defined as permafrost, so on land, permafrost is generally located beneath a so-called active layer of soil which freezes and thaws depending on the season.[38]

Around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface is underlain by permafrost,[39] covering a total area of around 18 million km2 (6.9 million sq mi).[40] This includes large areas of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Siberia. It is also located in high mountain regions, with the Tibetan Plateau being a prominent example. Only a minority of permafrost exists in the Southern Hemisphere, where it is consigned to mountain slopes like in the Andes of Patagonia, the Southern Alps of New Zealand, or the highest mountains of Antarctica.[37][35]

Permafrost contains large amounts of dead biomass that has accumulated throughout millennia without having had the chance to fully decompose and release its carbon, making tundra soil a carbon sink.[37] As global warming heats the ecosystem, frozen soil thaws and becomes warm enough for decomposition to start anew, accelerating the permafrost carbon cycle. Depending on conditions at the time of thaw, decomposition can release either carbon dioxide or methane, and these greenhouse gas emissions act as a climate change feedback.[41][42][43] The emissions from thawing permafrost will have a sufficient impact on the climate to impact global carbon budgets. It is difficult to accurately predict how much greenhouse gases the permafrost releases because the different thaw processes are still uncertain. There is widespread agreement that the emissions will be smaller than human-caused emissions and not large enough to result in runaway warming.[44] Instead, the annual permafrost emissions are likely comparable with global emissions from deforestation, or to annual emissions of large countries such as Russia, the United States or China.[45]Snow cover

[edit]

Most of the Earth's snow-covered area is located in the Northern Hemisphere, and varies seasonally from 46.5 million km2 in January to 3.8 million km2 in August.[46]

Snow cover is an extremely important storage component in the water balance, especially seasonal snowpacks in mountainous areas of the world. Though limited in extent, seasonal snowpacks in the Earth's mountain ranges account for the major source of the runoff for stream flow and groundwater recharge over wide areas of the midlatitudes. For example, over 85% of the annual runoff from the Colorado River basin originates as snowmelt. Snowmelt runoff from the Earth's mountains fills the rivers and recharges the aquifers that over a billion people depend on for their water resources.[citation needed]

Furthermore, over 40% of the world's protected areas are in mountains, attesting to their value both as unique ecosystems needing protection and as recreation areas for humans.[citation needed]

Ice on lakes and rivers

[edit]Ice forms on rivers and lakes in response to seasonal cooling. The sizes of the ice bodies involved are too small to exert anything other than localized climatic effects. However, the freeze-up/break-up processes respond to large-scale and local weather factors, such that considerable interannual variability exists in the dates of appearance and disappearance of the ice. Long series of lake-ice observations can serve as a proxy climate record, and the monitoring of freeze-up and break-up trends may provide a convenient integrated and seasonally-specific index of climatic perturbations. Information on river-ice conditions is less useful as a climatic proxy because ice formation is strongly dependent on river-flow regime, which is affected by precipitation, snow melt, and watershed runoff as well as being subject to human interference that directly modifies channel flow, or that indirectly affects the runoff via land-use practices.[citation needed]

Lake freeze-up depends on the heat storage in the lake and therefore on its depth, the rate and temperature of any inflow, and water-air energy fluxes. Information on lake depth is often unavailable, although some indication of the depth of shallow lakes in the Arctic can be obtained from airborne radar imagery during late winter (Sellman et al. 1975) and spaceborne optical imagery during summer (Duguay and Lafleur 1997). The timing of breakup is modified by snow depth on the ice as well as by ice thickness and freshwater inflow.[citation needed]

Changes caused by climate change

[edit]Ice sheet melt

[edit]

The Greenland ice sheet is an ice sheet which forms the second largest body of ice in the world. It is an average of 1.67 km (1.0 mi) thick and over 3 km (1.9 mi) thick at its maximum.[51] It is almost 2,900 kilometres (1,800 mi) long in a north–south direction, with a maximum width of 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) at a latitude of 77°N, near its northern edge.[52] The ice sheet covers 1,710,000 square kilometres (660,000 sq mi), around 80% of the surface of Greenland, or about 12% of the area of the Antarctic ice sheet.[51] The term 'Greenland ice sheet' is often shortened to GIS or GrIS in scientific literature.[53][54][55][56]

If all 2,900,000 cubic kilometres (696,000 cu mi) of the ice sheet were to melt, it would increase global sea levels by ~7.4 m (24 ft).[51] Global warming between 1.7 °C (3.1 °F) and 2.3 °C (4.1 °F) would likely make this melting inevitable.[56] However, 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) would still cause ice loss equivalent to 1.4 m (4+1⁄2 ft) of sea level rise,[57] and more ice will be lost if the temperatures exceed that level before declining.[56] If global temperatures continue to rise, the ice sheet will likely disappear within 10,000 years.[58][59] At very high warming, its future lifetime goes down to around 1,000 years.[60]

Beneath the Greenland ice sheet are mountains and lake basins.Decline of glaciers

[edit]

The retreat of glaciers since 1850 is a well-documented effect of climate change. The retreat of mountain glaciers provides evidence for the rise in global temperatures since the late 19th century. Examples include mountain glaciers in western North America, Asia, the Alps in central Europe, and tropical and subtropical regions of South America and Africa. Since glacial mass is affected by long-term climatic changes, e.g. precipitation, mean temperature, and cloud cover, glacial mass changes are one of the most sensitive indicators of climate change. The retreat of glaciers is also a major reason for sea level rise. Excluding peripheral glaciers of ice sheets, the total cumulated global glacial losses over the 26 years from 1993 to 2018 were likely 5500 gigatons, or 210 gigatons per year.[70]: 1275

On Earth, 99% of glacial ice is contained within vast ice sheets (also known as "continental glaciers") in the polar regions. Glaciers also exist in mountain ranges on every continent other than the Australian mainland, including Oceania's high-latitude oceanic island countries such as New Zealand. Glacial bodies larger than 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi) are called ice sheets.[71] They are several kilometers deep and obscure the underlying topography.Sea ice decline

[edit]

Sea ice reflects 50% to 70% of the incoming solar radiation back into space. Only 6% of incoming solar energy is reflected by the ocean.[73] As the climate warms, the area covered by snow or sea ice decreases. After sea ice melts, more energy is absorbed by the ocean, so it warms up. This ice-albedo feedback is a self-reinforcing feedback of climate change.[74] Large-scale measurements of sea ice have only been possible since satellites came into use.[75]

Sea ice in the Arctic has declined in recent decades in area and volume due to climate change. It has been melting more in summer than it refreezes in winter. The decline of sea ice in the Arctic has been accelerating during the early twenty-first century. It has a rate of decline of 4.7% per decade. It has declined over 50% since the first satellite records.[76][77][78] Ice-free summers are expected to be rare at 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) degrees of warming. They are set to occur at least once every decade with a warming level of 2 °C (3.6 °F).[79]: 8 The Arctic will likely become ice-free at the end of some summers before 2050.[80]: 9

Sea ice extent in Antarctica varies a lot year by year. This makes it difficult to determine a trend, and record highs and record lows have been observed between 2013 and 2023. The general trend since 1979, the start of the satellite measurements, has been roughly flat. Between 2015 and 2023, there has been a decline in sea ice, but due to the high variability, this does not correspond to a significant trend.[81]Permafrost thaw

[edit]

Snow cover decrease

[edit]

Studies in 2021 found that Northern Hemisphere snow cover has been decreasing since 1978, along with snow depth.[83] Paleoclimate observations show that such changes are unprecedented over the last millennia in Western North America.[84][85][83]

North American winter snow cover increased during the 20th century,[86][87] largely in response to an increase in precipitation.[88]

Because of its close relationship with hemispheric air temperature, snow cover is an important indicator of climate change.[citation needed]

Global warming is expected to result in major changes to the partitioning of snow and rainfall, and to the timing of snowmelt, which will have important implications for water use and management.[citation needed] These changes also involve potentially important decadal and longer time-scale feedbacks to the climate system through temporal and spatial changes in soil moisture and runoff to the oceans.(Walsh 1995). Freshwater fluxes from the snow cover into the marine environment may be important, as the total flux is probably of the same magnitude as desalinated ridging and rubble areas of sea ice.[89] In addition, there is an associated pulse of precipitated pollutants which accumulate over the Arctic winter in snowfall and are released into the ocean upon ablation of the sea ice.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Cryosphere - Maps and Graphics at UNEP/GRID-Arendal". 2007-08-26. Archived from the original on 2007-08-26. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ "Global Ice Viewer – Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet". climate.nasa.gov. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ a b Planton, S. (2013). "Annex III: Glossary" (PDF). In Stocker, T.F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.-K.; Tignor, M.; Allen, S.K.; Boschung, J.; Nauels, A.; Xia, Y.; Bex, V.; Midgley, P.M. (eds.). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- ^ σφαῖρα Archived 2017-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Hall, Dorothy K. (1985). Remote Sensing of Ice and Snow. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-94-009-4842-6.

- ^ "Properties of Snow – Our Winter World". ourwinterworld.org. Archived from the original on 2025-01-15. Retrieved 2025-03-06.

- ^ Groisman, Pavel Ya.; Karl, Thomas R.; Knight, Richard W. (14 January 1994). "Observed Impact of Snow Cover on the Heat Balance and the Rise of Continental Spring Temperatures". Science. 263 (5144): 198–200. Bibcode:1994Sci...263..198G. doi:10.1126/science.263.5144.198. PMID 17839175. S2CID 9932394. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Lynch-Stieglitz, M., 1994: The development and validation of a simple snow model for the GISS GCM. J. Climate, 7, 1842–1855.

- ^ Cohen, J., and D. Rind, 1991: The effect of snow cover on the climate. J. Climate, 4, 689–706.

- ^ a b Vernekar, A. D., J. Zhou, and J. Shukla, 1995: The effect of Eurasian snow cover on the Indian monsoon. J. Climate, 8, 248–266.

- ^ Curry, Judith A.; Schramm, Julie L.; Ebert, Elizabeth E. (1995). "Sea Ice-Albedo Climate Feedback Mechanism". Journal of Climate. 8 (2): 240–247. Bibcode:1995JCli....8..240C. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(1995)008<0240:SIACFM>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0894-8755.

- ^ Google Maps: Distance between Wildspitze and Hinterer Brochkogel, cf. image scale at lower edge of screen

- ^ Greve, R.; Blatter, H. (2009). Dynamics of Ice Sheets and Glaciers. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03415-2. ISBN 978-3-642-03414-5.

- ^ Paterson, W. S. B., 1993: World sea level and the present mass balance of the Antarctic ice sheet. In: W.R. Peltier (ed.), Ice in the Climate System, NATO ASI Series, I12, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 131–140.

- ^ Van den Broeke, M. R., 1996: The atmospheric boundary layer over ice sheets and glaciers. Utrecht, Universitiet Utrecht, 178 pp.

- ^ "Is glacier ice a type of rock?". United States Geological Survey. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 2025-02-06.

- ^ “Glacier, N., Pronunciation.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, June 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/7553486115. Accessed 25 Jan. 2025.

- ^ "Glacier Features - Mount Rainier National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved 18 January 2025.

- ^ "Geology, Geography, and Meteorology". The Ultimate Family Visual Dictionary. DK Pub. 2012. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-0-1434-1954-9.

- ^ Post, Austin; LaChapelle, Edward R (2000). Glacier ice. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97910-6.

- ^ Staff (June 9, 2020). "Millions at risk as melting Pakistan glaciers raise flood fears". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- ^ Craig, Tim (2016-08-12). "Pakistan has more glaciers than almost anywhere on Earth. But they are at risk". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

With 7,253 known glaciers, including 543 in the Chitral Valley, there is more glacial ice in Pakistan than anywhere on Earth outside the polar regions, according to various studies.

- ^ National Geographic Almanac of Geography, 2005, ISBN 0-7922-3877-X, p. 149.

- ^ "170'000 km cube d'eau dans les glaciers du monde". ArcInfo. Aug 6, 2015. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017.

- ^ "Ice, Snow, and Glaciers and the Water Cycle". www.usgs.gov. 8 September 2019. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Brown, Molly Elizabeth; Ouyang, Hua; Habib, Shahid; Shrestha, Basanta; Shrestha, Mandira; Panday, Prajjwal; Tzortziou, Maria; Policelli, Frederick; Artan, Guleid; Giriraj, Amarnath; Bajracharya, Sagar R.; Racoviteanu, Adina (November 2010). "HIMALA: Climate Impacts on Glaciers, Snow, and Hydrology in the Himalayan Region". Mountain Research and Development. 30 (4). International Mountain Society: 401–404. Bibcode:2010MRDev..30..401B. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-10-00071.1. hdl:2060/20110015312. S2CID 129545865.

- ^ American Meteorological Society, Glossary of Meteorology Archived 2012-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Glossary of Important Terms in Glacial Geology". Archived from the original on 2006-08-29. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ IPCC, 2021: Annex VII: Glossary [Matthews, J.B.R., V. Möller, R. van Diemen, J.S. Fuglestvedt, V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Méndez, S. Semenov, A. Reisinger (eds.)]. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2215–2256, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.022.

- ^ Sections 4.5 and 4.6 of Lemke, P.; Ren, J.; Alley, R.B.; Allison, I.; Carrasco, J.; Flato, G.; Fujii, Y.; Kaser, G.; Mote, P.; Thomas, R.H.; Zhang, T. (2007). "Observations: Changes in Snow, Ice and Frozen Ground" (PDF). In Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L. (eds.). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Zwally, H. J., J. C. Comiso, C. L. Parkinson, W. J. Campbell, F. D. Carsey, and P. Gloersen, 1983: Antarctic Sea Ice, 1973–1976: Satellite Passive-Microwave Observations. NASA SP-459, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., 206 pp.

- ^ a b c Gloersen, P., W. J. Campbell, D. J. Cavalieri, J. C. Comiso, C. L. Parkinson, and H. J. Zwally, 1992: Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice, 1978–1987: Satellite Passive-Microwave Observations and Analysis. NASA SP-511, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., 290 pp.

- ^ Parkinson, C. L., J. C. Comiso, H. J. Zwally, D. J. Cavalieri, P. Gloersen, and W. J. Campbell, 1987: Arctic Sea Ice, 1973–1976: Satellite Passive-Microwave Observations, NASA SP-489, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., 296 pp.

- ^ Parkinson, C. L., 1995: Recent sea-ice advances in Baffin Bay/Davis Strait and retreats in the Bellinshausen Sea. Annals of Glaciology, 21, 348–352.

- ^ a b McGee, David; Gribkoff, Elizabeth (4 August 2022). "Permafrost". MIT Climate Portal. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ "What is Permafrost?". International Permafrost Association. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Denchak, Melissa (26 June 2018). "Permafrost: Everything You Need to Know". Natural Resources Defense Council. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ Cooper, M. G.; Zhou, T.; Bennett, K. E.; Bolton, W. R.; Coon, E. T.; Fleming, S. W.; Rowland, J. C.; Schwenk, J. (4 January 2023). "Detecting Permafrost Active Layer Thickness Change From Nonlinear Baseflow Recession". Water Resources Research. 57 (1) e2022WR033154. Bibcode:2023WRR....5933154C. doi:10.1029/2022WR033154. S2CID 255639677.

- ^ Obu, J. (2021). "How Much of the Earth's Surface is Underlain by Permafrost?". Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. 126 (5) e2021JF006123. Bibcode:2021JGRF..12606123O. doi:10.1029/2021JF006123.

- ^ Sayedi, Sayedeh Sara; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Thornton, Brett F.; Frederick, Jennifer M.; Vonk, Jorien E.; Overduin, Paul; Schädel, Christina; Schuur, Edward A. G.; Bourbonnais, Annie; Demidov, Nikita; Gavrilov, Anatoly (22 December 2020). "Subsea permafrost carbon stocks and climate change sensitivity estimated by expert assessment". Environmental Research Letters. 15 (12): B027-08. Bibcode:2020AGUFMB027...08S. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abcc29. hdl:10852/83674. S2CID 234515282.

- ^ Schuur, T. (November 22, 2019). "Permafrost and the Global Carbon Cycle". Natural Resources Defense Council – via NOAA.

- ^ Koven, Charles D.; Ringeval, Bruno; Friedlingstein, Pierre; Ciais, Philippe; Cadule, Patricia; Khvorostyanov, Dmitry; Krinner, Gerhard; Tarnocai, Charles (6 September 2011). "Permafrost carbon-climate feedbacks accelerate global warming". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (36): 14769–14774. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10814769K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1103910108. PMC 3169129. PMID 21852573.

- ^ Galera, L. A.; Eckhardt, T.; Beer C., Pfeiffer E.-M.; Knoblauch, C. (22 March 2023). "Ratio of in situ CO2 to CH4 production and its environmental controls in polygonal tundra soils of Samoylov Island, Northeastern Siberia". Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences. 128 (4) e2022JG006956. Bibcode:2023JGRG..12806956G. doi:10.1029/2022JG006956. S2CID 257700504.

- ^ Fox-Kemper, B.; H. T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S. S. Drijfhout, T. L. Edwards, N. R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R. E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I. S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A. B. A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V.; P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, USA, pp. 1211–1362.

- ^ Schuur, Edward A. G.; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Commane, Roisin; Ernakovich, Jessica; Euskirchen, Eugenie; Hugelius, Gustaf; Grosse, Guido; Jones, Miriam; Koven, Charlie; Leshyk, Victor; Lawrence, David; Loranty, Michael M.; Mauritz, Marguerite; Olefeldt, David; Natali, Susan; Rodenhizer, Heidi; Salmon, Verity; Schädel, Christina; Strauss, Jens; Treat, Claire; Turetsky, Merritt (2022). "Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47: 343–371. Bibcode:2022ARER...47..343S. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011847. S2CID 252986002.

- ^ Robinson, D. A., K. F. Dewey, and R. R. Heim, 1993: Global snow cover monitoring: an update. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc., 74, 1689–1696.

- ^ Getting to Know the Cryosphere Archived 15 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Earth Labs

- ^ Thackeray, Chad W.; Derksen, Chris; Fletcher, Christopher G.; Hall, Alex (2019-12-01). "Snow and Climate: Feedbacks, Drivers, and Indices of Change". Current Climate Change Reports. 5 (4): 322–333. Bibcode:2019CCCR....5..322T. doi:10.1007/s40641-019-00143-w. ISSN 2198-6061. S2CID 201675060.

- ^ IPCC, 2019: Technical Summary [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Tignor, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.- O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 39–69. doi:10.1017/9781009157964.002

- ^ Beckmann, Johanna; Winkelmann, Ricarda (27 July 2023). "Effects of extreme melt events on ice flow and sea level rise of the Greenland Ice Sheet". The Cryosphere. 17 (7): 3083–3099. Bibcode:2023TCry...17.3083B. doi:10.5194/tc-17-3083-2023.

- ^ a b c "How Greenland would look without its ice sheet". BBC News. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Greenland Ice Sheet. 24 October 2023. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Tan, Ning; Ladant, Jean-Baptiste; Ramstein, Gilles; Dumas, Christophe; Bachem, Paul; Jansen, Eystein (12 November 2018). "Dynamic Greenland ice sheet driven by pCO2 variations across the Pliocene Pleistocene transition". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4755. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07206-w. PMC 6232173. PMID 30420596.

- ^ Noël, B.; van Kampenhout, L.; Lenaerts, J. T. M.; van de Berg, W. J.; van den Broeke, M. R. (19 January 2021). "A 21st Century Warming Threshold for Sustained Greenland Ice Sheet Mass Loss". Geophysical Research Letters. 48 (5) e2020GL090471. Bibcode:2021GeoRL..4890471N. doi:10.1029/2020GL090471. hdl:2268/301943. S2CID 233632072.

- ^ Höning, Dennis; Willeit, Matteo; Calov, Reinhard; Klemann, Volker; Bagge, Meike; Ganopolski, Andrey (27 March 2023). "Multistability and Transient Response of the Greenland Ice Sheet to Anthropogenic CO2 Emissions". Geophysical Research Letters. 50 (6) e2022GL101827. doi:10.1029/2022GL101827. S2CID 257774870.

- ^ a b c Bochow, Nils; Poltronieri, Anna; Robinson, Alexander; Montoya, Marisa; Rypdal, Martin; Boers, Niklas (18 October 2023). "Overshooting the critical threshold for the Greenland ice sheet". Nature. 622 (7983): 528–536. Bibcode:2023Natur.622..528B. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06503-9. PMC 10584691. PMID 37853149.

- ^ Christ, Andrew J.; Rittenour, Tammy M.; Bierman, Paul R.; Keisling, Benjamin A.; Knutz, Paul C.; Thomsen, Tonny B.; Keulen, Nynke; Fosdick, Julie C.; Hemming, Sidney R.; Tison, Jean-Louis; Blard, Pierre-Henri; Steffensen, Jørgen P.; Caffee, Marc W.; Corbett, Lee B.; Dahl-Jensen, Dorthe; Dethier, David P.; Hidy, Alan J.; Perdrial, Nicolas; Peteet, Dorothy M.; Steig, Eric J.; Thomas, Elizabeth K. (20 July 2023). "Deglaciation of northwestern Greenland during Marine Isotope Stage 11". Science. 381 (6655): 330–335. Bibcode:2023Sci...381..330C. doi:10.1126/science.ade4248. OSTI 1992577. PMID 37471537. S2CID 259985096.

- ^ Armstrong McKay, David; Abrams, Jesse; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Sakschewski, Boris; Loriani, Sina; Fetzer, Ingo; Cornell, Sarah; Rockström, Johan; Staal, Arie; Lenton, Timothy (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points". Science. 377 (6611) eabn7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950. hdl:10871/131584. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36074831. S2CID 252161375. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Archived from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Aschwanden, Andy; Fahnestock, Mark A.; Truffer, Martin; Brinkerhoff, Douglas J.; Hock, Regine; Khroulev, Constantine; Mottram, Ruth; Khan, S. Abbas (19 June 2019). "Contribution of the Greenland Ice Sheet to sea level over the next millennium". Science Advances. 5 (6): 218–222. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.9396A. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav9396. PMC 6584365. PMID 31223652.

- ^ Lau, Sally C. Y.; Wilson, Nerida G.; Golledge, Nicholas R.; Naish, Tim R.; Watts, Phillip C.; Silva, Catarina N. S.; Cooke, Ira R.; Allcock, A. Louise; Mark, Felix C.; Linse, Katrin (21 December 2023). "Genomic evidence for West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse during the Last Interglacial" (PDF). Science. 382 (6677): 1384–1389. Bibcode:2023Sci...382.1384L. doi:10.1126/science.ade0664. PMID 38127761. S2CID 266436146.

- ^ A. Naughten, Kaitlin; R. Holland, Paul; De Rydt, Jan (23 October 2023). "Unavoidable future increase in West Antarctic ice-shelf melting over the twenty-first century". Nature Climate Change. 13 (11): 1222–1228. Bibcode:2023NatCC..13.1222N. doi:10.1038/s41558-023-01818-x. S2CID 264476246.

- ^ Garbe, Julius; Albrecht, Torsten; Levermann, Anders; Donges, Jonathan F.; Winkelmann, Ricarda (2020). "The hysteresis of the Antarctic Ice Sheet". Nature. 585 (7826): 538–544. Bibcode:2020Natur.585..538G. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2727-5. PMID 32968257. S2CID 221885420.

- ^ a b Armstrong McKay, David; Abrams, Jesse; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Sakschewski, Boris; Loriani, Sina; Fetzer, Ingo; Cornell, Sarah; Rockström, Johan; Staal, Arie; Lenton, Timothy (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points". Science. 377 (6611) eabn7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950. hdl:10871/131584. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36074831. S2CID 252161375.

- ^ a b Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Fretwell, P.; et al. (28 February 2013). "Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica" (PDF). The Cryosphere. 7 (1): 390. Bibcode:2013TCry....7..375F. doi:10.5194/tc-7-375-2013. S2CID 13129041. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ Crotti, Ilaria; Quiquet, Aurélien; Landais, Amaelle; Stenni, Barbara; Wilson, David J.; Severi, Mirko; Mulvaney, Robert; Wilhelms, Frank; Barbante, Carlo; Frezzotti, Massimo (10 September 2022). "Wilkes subglacial basin ice sheet response to Southern Ocean warming during late Pleistocene interglacials". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 5328. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.5328C. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-32847-3. PMC 9464198. PMID 36088458.

- ^ Pan, Linda; Powell, Evelyn M.; Latychev, Konstantin; Mitrovica, Jerry X.; Creveling, Jessica R.; Gomez, Natalya; Hoggard, Mark J.; Clark, Peter U. (30 April 2021). "Rapid postglacial rebound amplifies global sea level rise following West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse". Science Advances. 7 (18) eabf7787. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.7787P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf7787. PMC 8087405. PMID 33931453.

- ^ "Vanishing glaciers of Alaska". CBS News. 1 September 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022.

- ^ Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011.

- ^ "Glossary of Meteorology". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2012-06-23. Retrieved 2013-01-04.

- ^ Purich, Ariaan; Doddridge, Edward W. (13 September 2023). "Record low Antarctic sea ice coverage indicates a new sea ice state". Communications Earth & Environment. 4 (1): 314. Bibcode:2023ComEE...4..314P. doi:10.1038/s43247-023-00961-9. S2CID 261855193.

- ^ "Thermodynamics: Albedo | National Snow and Ice Data Center". nsidc.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "How does sea ice affect global climate?". NOAA. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Arctic Report Card 2012". NOAA. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ Huang, Yiyi; Dong, Xiquan; Bailey, David A.; Holland, Marika M.; Xi, Baike; DuVivier, Alice K.; Kay, Jennifer E.; Landrum, Laura L.; Deng, Yi (2019-06-19). "Thicker Clouds and Accelerated Arctic Sea Ice Decline: The Atmosphere-Sea Ice Interactions in Spring". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (12): 6980–6989. Bibcode:2019GeoRL..46.6980H. doi:10.1029/2019gl082791. hdl:10150/634665. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 189968828.

- ^ Senftleben, Daniel; Lauer, Axel; Karpechko, Alexey (2020-02-15). "Constraining Uncertainties in CMIP5 Projections of September Arctic Sea Ice Extent with Observations". Journal of Climate. 33 (4): 1487–1503. Bibcode:2020JCli...33.1487S. doi:10.1175/jcli-d-19-0075.1. ISSN 0894-8755. S2CID 210273007.

- ^ Yadav, Juhi; Kumar, Avinash; Mohan, Rahul (2020-05-21). "Dramatic decline of Arctic sea ice linked to global warming". Natural Hazards. 103 (2): 2617–2621. Bibcode:2020NatHa.103.2617Y. doi:10.1007/s11069-020-04064-y. ISSN 0921-030X. S2CID 218762126.

- ^ IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3-24. doi:10.1017/9781009157940.001.

- ^ Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011

- ^ "Understanding climate: Antarctic sea ice extent". NOAA Climate.gov. 14 March 2023. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ Carrer, Marco; Dibona, Raffaella; Prendin, Angela Luisa; Brunetti, Michele (February 2023). "Recent waning snowpack in the Alps is unprecedented in the last six centuries". Nature Climate Change. 13 (2): 155–160. Bibcode:2023NatCC..13..155C. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01575-3. hdl:11577/3477269. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ a b Fox-Kemper, B.; Hewitt, H.T.; Xiao, C.; Aðalgeirsdóttir, G.; Drijfhout, S.S.; Edwards, T.L.; Golledge, N.R.; Hemer, M.; Kopp, R.E.; Krinner, G.; Mix, A. (2021). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L. (eds.). "Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change" (PDF). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2021. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: 1283–1285. doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011. ISBN 9781009157896.

- ^ Pederson, Gregory T.; Gray, Stephen T.; Woodhouse, Connie A.; Betancourt, Julio L.; Fagre, Daniel B.; Littell, Jeremy S.; Watson, Emma; Luckman, Brian H.; Graumlich, Lisa J. (2011-07-15). "The Unusual Nature of Recent Snowpack Declines in the North American Cordillera". Science. 333 (6040): 332–335. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..332P. doi:10.1126/science.1201570. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21659569. S2CID 29486298.

- ^ Belmecheri, Soumaya; Babst, Flurin; Wahl, Eugene R.; Stahle, David W.; Trouet, Valerie (2016). "Multi-century evaluation of Sierra Nevada snowpack". Nature Climate Change. 6 (1): 2–3. Bibcode:2016NatCC...6....2B. doi:10.1038/nclimate2809. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ Brown, Ross D.; Goodison, Barry E.; Brown, Ross D.; Goodison, Barry E. (1996-06-01). "Interannual Variability in Reconstructed Canadian Snow Cover, 1915–1992". Journal of Climate. 9 (6): 1299–1318. Bibcode:1996JCli....9.1299B. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(1996)009<1299:ivircs>2.0.co;2.

- ^ Hughes, M. G.; Frei, A.; Robinson, D.A. (1996). "Historical analysis of North American snow cover extent: merging satellite and station-derived snow cover observations". Proceedings of the Annual Meeting - Eastern Snow Conference. Williamsburg, Virginia: Eastern Snow Conference. pp. 21–31. ISBN 9780920081181.

- ^ Groisman, P. Ya, and D. R. Easterling, 1994: Variability and trends of total precipitation and snowfall over the United States and Canada. J. Climate, 7, 184–205.

- ^ Prinsenberg, S. J. 1988: Ice-cover and ice-ridge contributions to the freshwater contents of Hudson Bay and Foxe Basin. Arctic, 41, 6–11.

External links

[edit]Cryosphere

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Definition and Scope

The cryosphere comprises those parts of Earth's surface where water is in frozen form, including continental ice sheets, glaciers, permafrost, seasonal snow cover, river and lake ice, and sea ice.[9][4] This frozen realm exists under sub-zero temperatures that maintain water's solid state, distinguishing it from liquid or vapor phases in the broader hydrosphere.[10] The term "cryosphere" derives from the Greek "kryos," signifying cold, frost, or ice, combined with "sphaira," meaning globe or sphere, thus denoting the planet's cold, icy envelope.[11] Geographically, the cryosphere spans polar regions, high mountain chains, and even mid-latitude areas during winter, occurring in roughly one hundred countries across all latitudes, though concentrated in the Arctic, Antarctic, and alpine zones.[11] Permanent ice from glaciers and ice sheets covers about 10% of Earth's land area, while seasonal elements like snow and sea ice expand its temporary footprint significantly.[5] These components interact dynamically with the atmosphere, oceans, and land, influencing global energy balance through high albedo and freshwater storage—holding approximately 70% of Earth's freshwater reserves.[5][12] The scope excludes atmospheric ice like clouds or hail, focusing solely on surface and near-surface frozen water, which varies in scale from vast Antarctic ice sheets (spanning 14 million km²) to transient river ice formations.[9] This delineation underscores the cryosphere's role as a distinct subsystem within Earth's climate machinery, responsive to thermal forcings yet integral to long-term hydrological cycles.[13]Terminology and Classification

The term cryosphere originates from the Greek word krios, meaning "icy cold," and denotes the portions of Earth's surface where water exists in solid form due to temperatures at or below 0°C, encompassing all frozen elements of the hydrologic cycle.[9] This includes both perennial and seasonal features, such as ice sheets covering vast continental areas and transient snow accumulations.[4] Key components are defined by their physical state, location, and persistence. Ice sheets are expansive masses of land-based ice exceeding 50,000 km² in area, exemplified by the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, which store over 70% of Earth's freshwater as ice.[9] Glaciers and ice caps, smaller than ice sheets, consist of compacted snow that deforms and flows under its own weight; ice caps are distinguished as those under 50,000 km², often atop mountains or plateaus.[9] Sea ice forms from frozen seawater in polar oceans, freezing at approximately -1.8°C due to salinity effects, and is categorized by age into first-year (one season) and multi-year ice.[9] Permafrost refers to ground remaining below 0°C for at least two consecutive years, underlying about 24% of the Northern Hemisphere's land surface, while seasonally frozen ground thaws annually above a permafrost active layer.[9] Snow cover arises from precipitated ice crystals, providing insulation and high albedo, whereas lake and river ice covers freshwater bodies in colder regions.[9] Classification schemes typically divide the cryosphere into terrestrial and marine domains to reflect interactions with land and ocean systems. Terrestrial components include land ice (glaciers, ice sheets, ice caps), frozen ground (permafrost and seasonal frost), and snow cover, which dominate freshwater storage and continental hydrology.[14] Marine components, primarily sea ice, influence ocean circulation and atmospheric heat exchange without contributing to sea-level rise upon melting, unlike land ice.[4] Additional categorizations consider residence time—perennial (e.g., ice sheets, permafrost) versus seasonal (e.g., snow cover, river ice)—or by form, such as freshwater ice (lakes, rivers) distinct from saline sea ice.[14] These distinctions aid in monitoring cryospheric responses to temperature variations, with organizations like the Global Cryosphere Watch standardizing terminology across components including snow, freshwater ice, glaciers, ice sheets, and permafrost.[14]Physical Properties

Thermal and Mechanical Properties

Ice in the cryosphere exhibits distinct thermal properties that influence heat transfer and phase changes. Pure ice has a specific heat capacity of approximately 2.097 J/g/K at 0°C, decreasing to 1.741 J/g/K at -50°C, which is roughly half that of liquid water.[15] Its thermal conductivity is about 2.3 W/m/K, enabling efficient conduction compared to air but varying with impurities and temperature.[16] The latent heat of fusion for ice is 334 kJ/kg, absorbing significant energy during melting without temperature change, a process critical to cryospheric energy balances.[16] Snow and firn display lower thermal conductivities due to their porous structures, acting as insulators. Snow's thermal conductivity ranges from 0.33 to 0.47 W/m/K, with a median of 0.39 W/m/K in Arctic conditions, reducing heat flux from underlying surfaces to the atmosphere by up to orders of magnitude relative to bare ground.[17] Firn, transitional between snow and ice, has conductivity increasing with density, reaching up to 2.4 W/m/K at ice densities, affecting heat diffusion in ice sheets.[18] Sea ice incorporates brine pockets, lowering effective conductivity and altering latent heat transfer during freeze-thaw cycles.[19] In permafrost regions, snow cover's insulation preserves ground ice by limiting winter conductive heat loss, with conductivity schemes varying by snow type influencing modeled permafrost stability.[20] Mechanically, cryospheric ice behaves as a viscoelastic material, combining elastic, delayed elastic, and viscous responses under stress.[21] Glacier ice deforms primarily through creep, following Glen's flow law where strain rate is proportional to the third power of deviatoric stress, enabling slow plastic flow over geological timescales.[22] At low strain rates, viscous creep dominates, while higher rates induce brittle fracture or elastic behavior, as seen in sea ice floe interactions.[23] Polycrystalline ice strength depends on grain size, fabric, and temperature; colder ice (-50°C) resists deformation more than temperate ice near 0°C due to reduced dislocation mobility.[24] Brine inclusions in sea ice weaken mechanical integrity, promoting frictional sliding and ridging under compressive forces.[25] These properties govern cryospheric dynamics, from glacier surging to sea ice pack deformation, with flow laws calibrated against laboratory data spanning 70 years confirming non-linear viscous rheology for ice sheets.[22]Extent, Volume, and Residence Time

The cryosphere encompasses diverse frozen components with varying spatial extents. The Antarctic Ice Sheet covers approximately 14 million km², while the Greenland Ice Sheet spans about 1.71 million km².[26] Glaciers and ice caps outside these major ice sheets occupy roughly 706,000 to 726,000 km² globally.[27] Permafrost underlies 14 to 23 million km² in the Northern Hemisphere, representing 15% to 24% of exposed land there.[28] [29] Sea ice extent varies seasonally: Arctic averages 14-15 million km² at winter maximum and 4-5 million km² at summer minimum, while Antarctic reaches 17-18 million km² maximum and 2-3 million km² minimum.[30] [31] Northern Hemisphere snow cover averages 24 million km² annually.[32] Ice volumes are dominated by continental ice sheets. The Antarctic Ice Sheet holds about 26.5 million km³, equivalent to 58 meters of global sea level rise if fully melted. The Greenland Ice Sheet contains approximately 2.9 million km³, corresponding to 7.4 meters sea level equivalent.[33] Glaciers outside ice sheets store 158,000 to 170,000 km³, or 0.32 to 0.4 meters sea level equivalent after adjusting for bedrock below sea level.[34] [35] Sea ice volumes are smaller and seasonal, with Arctic peaks around 15,000-20,000 km³ and Antarctic higher but variable. Permafrost ground ice volume is estimated in tens of thousands of km³ but dispersed in soil. Total land ice volume exceeds 29 million km³, primarily from ice sheets.[6] Residence times differ markedly across components, reflecting formation and persistence timescales. Snow cover persists seasonally, from days to months. Sea ice has residence times of 1 to 10 years, with first-year ice turning over annually and older multi-year ice rarer. Glaciers exhibit decadal to centennial turnover, depending on size and location. Ice sheets involve millennial to multimillennial scales, with deep interior ice aged tens of thousands of years. Permafrost can remain frozen for thousands to millions of years, though active layer thaws annually.[36] These timescales influence cryospheric responses to climatic forcing, with shorter-residence elements more sensitive to annual variations.Surface Properties

The surfaces of cryospheric components exhibit high albedo, typically reflecting 50% to 90% of incoming solar radiation, which plays a critical role in Earth's energy balance by limiting absorption of shortwave radiation. Fresh snow albedo ranges from 0.80 to 0.90, while snow-covered sea ice can reach up to 0.90, enhancing reflectivity compared to bare ice. Bare sea ice albedo is generally 0.65 to 0.70, decreasing to 0.5 or lower during melt seasons due to ponding, grain metamorphism, and impurities like black carbon that reduce reflectivity.[37][19][38] Albedo variations are influenced by factors such as solar zenith angle, surface microstructure, and wavelength, with small-scale roughness potentially lowering total albedo by up to 0.10 through increased multiple scattering and trapping of light.[39] Aerodynamic surface roughness, quantified by the roughness length , governs momentum and heat exchange between the cryosphere and atmosphere, affecting turbulent fluxes in models of snowpack evolution and ice-atmosphere interactions. For fresh snow under rough flow conditions, averages approximately 0.24 mm, while smoother surfaces like interior ice sheets exhibit values as low as m, escalating to m over hummocky or sastrugi-formed terrain.[40][41] These parameters are derived from field measurements and eddy covariance data, underscoring the need for site-specific parameterization in simulations, as dynamic roughness alters snowpack thermal profiles and ablation rates.[42] In the thermal infrared, cryospheric surfaces display high emissivity, approximating blackbody behavior and facilitating efficient longwave radiation emission. Snow and ice emissivity reaches 0.98 to 0.99, enabling accurate retrieval of surface skin temperatures from satellite infrared sensors, though values vary slightly with grain size, viewing angle, and contaminants.[43] This property contrasts with lower microwave emissivities used in sea ice detection, highlighting wavelength-dependent radiative behavior essential for remote sensing and energy budget calculations.[44]Components of the Cryosphere

Glaciers and Ice Sheets

Glaciers form where the accumulation of snow exceeds melting and sublimation over multiple years, leading to the compaction of snow into ice that deforms plastically and flows downslope under its own weight due to gravity. This flow occurs through internal deformation of ice crystals and basal sliding over the underlying terrain, with rates varying from centimeters to hundreds of meters per year depending on slope, thickness, and temperature. Ice sheets represent the largest class of glaciers, defined as contiguous ice masses exceeding 50,000 km² that blanket entire continents or large islands, overriding underlying topography and spreading radially outward from high-elevation domes. The two extant ice sheets are the Antarctic Ice Sheet and the Greenland Ice Sheet, which together store approximately 68% of global fresh water and influence regional climate through albedo effects and freshwater discharge. The Antarctic Ice Sheet covers about 13.61 million km², encompassing nearly 98% of the Antarctic continent, with an average thickness of 1.9 km and maximum depths exceeding 4.5 km in East Antarctica. Its volume totals roughly 26.5 million km³, equivalent to 58.3 meters of global mean sea level rise if fully melted. The East Antarctic Ice Sheet, comprising 80% of the total, is largely stable or gaining mass in interior regions due to increased snowfall, while the West Antarctic Ice Sheet shows greater variability and net loss primarily from enhanced iceberg calving and surface melting. Mass balance assessments from satellite altimetry, gravimetry, and input-output methods indicate a net loss of 2,720 ± 1,390 gigatons from 1992 to 2020, with the rate accelerating to 142 ± 49 Gt yr⁻¹ in the 2010s, though uncertainties remain high due to challenges in partitioning accumulation changes and oceanic forcing. These losses contribute to sea level rise but are modulated by compensatory snowfall increases linked to warmer atmospheric moisture capacity. The Greenland Ice Sheet spans 1.71 million km², with an average thickness of 1.6 km and maxima up to 3.4 km near the summit. Its volume is approximately 2.96 million km³, corresponding to 7.4 meters of sea level equivalent. Unlike Antarctica, Greenland experiences significant surface melting in summer, amplified by albedo feedback from melt ponds, with mass loss dominated by runoff (about 50%) and calving (about 50%) in recent decades. The Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise (IMBIE) reports a cumulative loss of 4,890 Gt from 1992 to 2020, with an average rate of 169 Gt yr⁻¹ increasing to 234 Gt yr⁻¹ after 2010, driven by marine-terminating outlet glaciers' rapid retreat and thinning. Interior accumulation has risen slightly from enhanced precipitation, offsetting some peripheral losses, but net imbalance persists, with gravimetric data confirming acceleration linked to submarine melting from Atlantic Water intrusion. Beyond ice sheets, glaciers number approximately 215,000 worldwide outside Antarctica and Greenland, covering a total area of about 680,000 km² as of inventories from the early 2000s, though ongoing retreat has reduced this extent. These include valley glaciers, ice caps, and piedmont glaciers primarily in mountain ranges like the Alps, Himalayas, Andes, and Alaska, where they respond sensitively to temperature and precipitation changes. Global glacier mass loss averaged -1.0 m water equivalent per year from 2000 to 2019, totaling over 21,000 Gt, equivalent to 58 mm of sea level rise, with acceleration in low-latitude regions due to reduced accumulation and increased melt. Observations from repeat airborne and satellite surveys, such as those by NASA's Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) mission, highlight causal drivers including black carbon deposition lowering albedo and geothermal heat flux beneath thin ice. Regional variations exist, with some temperate glaciers showing surging behavior from hydrological feedbacks, underscoring that mass balance is not uniformly negative but governed by local topography and microclimate.| Major Ice Masses | Area (million km²) | Volume (million km³) | Sea Level Equivalent (m) | Primary Mass Loss Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antarctic Ice Sheet | 13.61 | 26.5 | 58.3 | Calving and basal melt |

| Greenland Ice Sheet | 1.71 | 2.96 | 7.4 | Surface melt and calving |

| Non-polar Glaciers | 0.68 | 0.24 | 0.63 | Surface ablation |

Sea Ice

Sea ice consists of frozen seawater that forms and floats on the ocean surface in polar regions. It develops through the freezing of seawater, which occurs at temperatures below -1.8°C due to the presence of salts, lower than the freezing point of pure water at 0°C.[45][46] This process rejects brine, creating a porous structure with lower salinity than the underlying ocean water, typically around 4-5 parts per thousand compared to seawater's 35.[47] Sea ice exhibits pronounced seasonal variability, expanding during winter and contracting in summer in both the Arctic and Antarctic. In the Arctic Ocean, which is semi-enclosed, sea ice reaches its maximum extent in March, covering up to 14-16 million square kilometers historically, and minimum in September. The Antarctic, surrounding the continent, sees maximum extent in September, historically around 18-20 million square kilometers, and minimum in February. Multi-year ice persists in the Arctic, while Antarctic sea ice is predominantly annual.[45][48] Physically, sea ice has a density of about 920 kg/m³, causing it to float with roughly 10% above water. Thickness varies from thin nilas (centimeters) to deformed ridges exceeding 10 meters, though average Arctic thickness is 1-3 meters and Antarctic 0.5-1 meter. Its high albedo, ranging from 0.5 to 0.7 for snow-covered ice, contrasts sharply with the ocean's 0.06, reflecting most incoming solar radiation. Sea ice also insulates the underlying ocean, limiting winter heat loss to the atmosphere by up to 90%.[19][49] Observed trends show Arctic sea ice extent declining markedly since satellite records began in 1979, with summer minima decreasing at approximately 13% per decade. The 2025 Arctic maximum extent on March 22 was the lowest in the 47-year record, while the September minimum of 4.60 million square kilometers ranked among the ten lowest. Antarctic trends were modestly positive until the mid-2010s but have since shown variability with recent record lows; the 2025 maximum of 17.81 million square kilometers on September 30 was the third lowest on record. Volume estimates indicate Arctic losses exceeding 50% since 1979, driven primarily by thinning.[50][51][52] In the climate system, sea ice modulates energy exchanges by enhancing planetary albedo, reducing absorbed solar heat in polar regions. Its retreat amplifies warming via the ice-albedo feedback, where exposed darker ocean absorbs more radiation, further melting ice. Additionally, sea ice formation drives thermohaline circulation through brine rejection, producing dense water that sinks and contributes to global ocean overturning. It barriers wind-driven mixing and influences atmospheric moisture and salinity fluxes.[19][53][47]Permafrost and Frozen Ground

Permafrost consists of soil, sediment, rock, and included ice or organic material that remains at or below 0°C continuously for at least two consecutive years.[54][55] This perennial frozen state distinguishes it from seasonally frozen ground, which thaws annually and freezes for more than 15 days per year, or intermittently frozen ground that freezes for fewer than 15 days.[54][56] Above the permafrost lies the active layer, a surface zone that thaws during summer and refreezes in winter, typically ranging from 30 cm to several meters in depth depending on climate, vegetation, and soil properties.[57] Permafrost underlies approximately 14 to 16 million km² of the Northern Hemisphere's exposed land surface, equivalent to about 15% of the total, with continuous permafrost in polar regions and discontinuous or sporadic zones toward lower latitudes and elevations.[28][58] It also occurs in subsea sediments beneath Arctic continental shelves, high mountain ranges like the Alps and Rockies, and limited areas in Antarctica.[54] Ground ice within permafrost exists in forms such as pore ice filling sediment voids, segregated ice lenses formed by water migration, and massive ice wedges or blocks resulting from thermal contraction cracks. Ice content varies widely, from ice-poor dry permafrost to ice-rich layers exceeding 90% ice volume by weight in some Arctic lowlands, influencing stability and thaw susceptibility.[59] Permafrost regions store an estimated 1,460 to 1,700 petagrams of organic carbon, roughly twice the amount currently in Earth's atmosphere, accumulated over millennia in frozen soils and peat.[60][61] Thawing permafrost, driven by rising air temperatures, can release this carbon as carbon dioxide and methane through microbial decomposition, potentially amplifying global warming, while also causing ground subsidence, thermokarst lake formation, and infrastructure instability in affected areas.[57][62] Recent observations indicate active layer thickening and permafrost temperature increases of up to 0.3–0.4°C per decade in continuous zones since the 1980s.[57]Snow Cover and Seasonal Ice

Snow cover constitutes the seasonal accumulation of solidified precipitation on terrestrial surfaces, forming a transient yet extensive component of the cryosphere that influences regional albedo, hydrology, and energy budgets. In the Northern Hemisphere, where the majority of seasonal snow occurs, maximum extent typically reaches 46 to 47 million square kilometers during January, covering roughly 10% of the land surface and spanning Eurasia and North America.[63][64] Minimum extent contracts to about 2 million square kilometers by late summer, primarily residual in high-latitude or high-elevation regions.[64] Southern Hemisphere snow cover remains limited, averaging 0.5 to 2 million square kilometers annually, concentrated in the Andes, Patagonia, and Antarctic coastal areas during austral winter.[65] Satellite observations, initiated in 1967 by NOAA and processed by Rutgers University's Global Snow Lab, provide the primary record of Northern Hemisphere snow cover extent (SCE), combining weekly charts from 1967 to 1999 with daily visible-band imagery thereafter.[66] These data reveal a pronounced seasonal cycle, with accumulation driven by winter precipitation and ablation governed by spring warming, resulting in snow persistence durations of 100 to 250 days across mid-to-high latitudes.[67] Regional variations are stark: Eurasia hosts over 60% of NH maximum SCE due to vast continental interiors, while North American cover correlates more closely with mid-latitude storm tracks.[65] Snow water equivalent (SWE), a measure of stored water volume, peaks at 200 to 500 millimeters in continental interiors but exhibits high interannual variability tied to precipitation anomalies.[68] Seasonal ice, encompassing ephemeral formations such as ice crusts, depth hoar layers within snowpacks, and aufeis (spring-fed ice sheets in permafrost margins), integrates with snow cover to modulate subsurface heat exchange and runoff.[11] These features arise from freeze-thaw cycles, with ice lenses forming via capillary action in porous snow or soil, enhancing structural stability but accelerating melt through insulation effects. In Arctic and subarctic zones, seasonal ground ice contributes to active layer dynamics, thawing annually to depths of 0.3 to 2 meters while preserving underlying permafrost.[9] Observational trends from 1981 to 2018 indicate negative SCE anomalies in the Northern Hemisphere across all months, with rates exceeding 50,000 square kilometers per year in November, December, March, and May, attributed to warmer spring temperatures advancing melt onset by 1 to 2 weeks per decade in many regions.[65] April snow mass, a proxy for pre-melt storage, declined 4.3% per decade through 2016, reflecting reduced accumulation efficiency amid variable precipitation.[68] However, annual maximum SCE exhibits relative stability since the 1970s, with fluctuations linked to large-scale modes like the North Atlantic Oscillation rather than monotonic decline.[64] These patterns underscore snow cover's sensitivity to hemispheric circulation shifts, with low-elevation sites showing more pronounced reductions than high-elevation refugia.[69] Monitoring continues via passive microwave sensors (e.g., SSM/I) for all-weather SWE estimates and MODIS optical data for fractional cover, enabling detection of sub-grid variability down to 500-meter resolution.[70]Lake and River Ice

Lake and river ice forms on inland water bodies in regions where sustained subfreezing air temperatures cause surface cooling and eventual solidification, typically in the Northern Hemisphere's higher latitudes and altitudes.[71] This seasonal ice cover influences local heat exchange, hydrological regimes, and ecosystems by insulating water from atmospheric conditions during winter.[72] Unlike perennial cryospheric components such as glaciers, lake and river ice undergoes annual freeze-up, maximum extent, and break-up cycles driven primarily by air temperature thresholds around 0°C, modulated by factors like water depth, currents, snowfall, and solar radiation.[73] The phenological cycle begins with freeze-up, when ice nucleation spreads across the surface, often starting in shallow margins and progressing inward; this process can take days to weeks depending on turbulence and wind.[74] Maximum ice thickness, typically 0.5–2 meters in temperate lakes and thinner on fast-flowing rivers, accumulates through thermodynamic growth and snow loading before break-up initiates via rising temperatures, melting, and mechanical forces like wave action or ice jams.[75] Ice duration varies regionally: in subarctic zones, it spans 4–6 months, while in milder climates like the Great Lakes, it averages 2–3 months with interannual variability tied to winter severity.[76] Historical records, compiled in databases like the Global Lake and River Ice Phenology Database encompassing 865 sites, reveal consistent trends toward diminished ice seasons across the Northern Hemisphere.[77] Analysis of 3510 time series from 678 water bodies indicates later freeze-up dates by approximately 1–2 days per decade and earlier break-up by 2–3 days per decade over the 20th century, shortening ice-covered periods by 2–5 days per decade on average.[71] Longer paleorecords, some extending to the 16th century, show initial reductions in ice cover accelerating post-1850, with a notable regime shift in North American lakes around the late 1980s coinciding with amplified warming.[78][79] For rivers, 56% of monitored segments exhibit delayed freeze-up by 2.7 days per decade, though trends are less uniform due to hydrological influences like flow velocity.[80] Monitoring employs a mix of in-situ observations, such as thermistor chains and visual logs, alongside remote sensing techniques including passive microwave radiometry for freeze-thaw detection and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) for mapping ice extent and thickness.[81][82] Satellite datasets, like ESA's Climate Change Initiative lake ice records since 2001, provide near-global coverage at resolutions down to 250–500 meters, enabling daily tracking of ice phenology.[83] Web-based cameras and unmanned aerial vehicles supplement these for real-time river ice dynamics, particularly jam formation risks.[84][85] These methods confirm ongoing declines, with projections under warming scenarios estimating 10–28 additional days of ice loss per century in vulnerable regions.[79]Role in Global Systems

Climate Feedbacks

The cryosphere exerts significant influence on Earth's climate through various feedback mechanisms, predominantly positive ones that amplify warming. These feedbacks arise from interactions between ice, snow, permafrost, and atmospheric processes, altering energy balances and greenhouse gas concentrations. Empirical observations and modeling indicate that reductions in cryospheric extent enhance radiative forcing, with albedo changes and carbon releases contributing substantially to global temperature sensitivity.[86] A primary feedback is the ice-albedo effect, where melting of high-albedo surfaces like sea ice and snow exposes darker ocean or land, increasing solar absorption and accelerating melt. In the Arctic, sea ice loss has decreased regional albedo by approximately 3% per decade in August, intensifying local warming through this positive loop. Ice sheet-albedo feedback alone amplifies the total climate feedback parameter by 42%, equivalent to 0.55 W/m² per Kelvin of warming. Cloud-albedo interactions further enhance Greenland Ice Sheet sensitivity in recent climate models.[87][88][89] Permafrost thaw triggers a carbon feedback by releasing stored organic matter as CO₂ and CH₄ upon decomposition, potentially adding 6 to 118 petagrams of carbon by 2100 under varying scenarios. This process is gradual, spanning decades to centuries, and is regulated by soil temperature, carbon quantity, and ice content, with abrupt thaw events exacerbating emissions in vulnerable regions like Siberia. Such releases could reduce carbon budgets for limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2°C by up to 20-22%.[90][91][92][93] Additional feedbacks include ice sheet elevation changes, where surface lowering reduces atmospheric lapse rates, exposing ice to warmer air and hastening mass loss, as seen in Greenland simulations. Sea ice decline also perturbs ocean circulation and moisture fluxes, potentially altering cloud cover and hemispheric energy transport. While some negative feedbacks exist, such as increased freshwater stabilizing stratification, positive mechanisms dominate, contributing to polar amplification observed since the 20th century.[94][86]Hydrological and Biogeochemical Cycles