Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Conformal map

View on Wikipedia

| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

| Complex numbers |

| Basic theory |

| Complex functions |

| Theorems |

| Geometric function theory |

| People |

In mathematics, a conformal map is a function that locally preserves angles, but not necessarily lengths.

More formally, let and be open subsets of . A function is called conformal (or angle-preserving) at a point if it preserves angles between directed curves through , as well as preserving orientation. Conformal maps preserve both angles and the shapes of infinitesimally small figures, but not necessarily their size or curvature.

The conformal property may be described in terms of the Jacobian derivative matrix of a coordinate transformation. The transformation is conformal whenever the Jacobian at each point is a positive scalar times a rotation matrix (orthogonal with determinant one). Some authors define conformality to include orientation-reversing mappings whose Jacobians can be written as any scalar times any orthogonal matrix.[1]

For mappings in two dimensions, the (orientation-preserving) conformal mappings are precisely the locally invertible complex analytic functions. In three and higher dimensions, Liouville's theorem sharply limits the conformal mappings to a few types.

The notion of conformality generalizes in a natural way to maps between Riemannian or semi-Riemannian manifolds.

In two dimensions

[edit]If is an open subset of the complex plane , then a function is conformal if and only if it is holomorphic and its derivative is everywhere non-zero on . If is antiholomorphic (complex conjugate to a holomorphic function), it preserves angles but reverses their orientation.

In the literature, there is another definition of conformal: a mapping which is one-to-one and holomorphic on an open set in the plane. The open mapping theorem forces the inverse function (defined on the image of ) to be holomorphic. Thus, under this definition, a map is conformal if and only if it is biholomorphic. The two definitions for conformal maps are not equivalent. Being one-to-one and holomorphic implies having a non-zero derivative. In fact, we have the following relation, the inverse function theorem:

where . However, the exponential function is a holomorphic function with a nonzero derivative, but is not one-to-one since it is periodic.[2]

The Riemann mapping theorem, one of the profound results of complex analysis, states that any non-empty open simply connected proper subset of admits a bijective conformal map to the open unit disk in . Informally, this means that any blob can be transformed into a perfect circle by some conformal map.

Global conformal maps on the Riemann sphere

[edit]A map of the Riemann sphere onto itself is conformal if and only if it is a Möbius transformation.

The complex conjugate of a Möbius transformation preserves angles, but reverses the orientation. For example, circle inversions.

Conformality with respect to three types of angles

[edit]In plane geometry there are three types of angles that may be preserved in a conformal map.[3] Each is hosted by its own real algebra, ordinary complex numbers, split-complex numbers, and dual numbers. The conformal maps are described by linear fractional transformations in each case.[4]

In three or more dimensions

[edit]Riemannian geometry

[edit]In Riemannian geometry, two Riemannian metrics and on a smooth manifold are called conformally equivalent if for some positive function on . The function is called the conformal factor.

A diffeomorphism between two Riemannian manifolds is called a conformal map if the pulled back metric is conformally equivalent to the original one. For example, stereographic projection of a sphere onto the plane augmented with a point at infinity is a conformal map.

One can also define a conformal structure on a smooth manifold, as a class of conformally equivalent Riemannian metrics.

Euclidean space

[edit]A classical theorem of Joseph Liouville shows that there are far fewer conformal maps in higher dimensions than in two dimensions. Any conformal map from an open subset of Euclidean space into the same Euclidean space of dimension three or greater can be composed from three types of transformations: a homothety, an isometry, and a special conformal transformation. For linear transformations, a conformal map may only be composed of homothety and isometry, and is called a conformal linear transformation.

Applications

[edit]Applications of conformal mapping exist in aerospace engineering,[5] in biomedical sciences[6] (including brain mapping[7] and genetic mapping[8][9][10]), in applied math (for geodesics[11] and in geometry[12]), in earth sciences (including geophysics,[13] geography,[14] and cartography),[15] in engineering,[16][17] and in electronics.[18]

Cartography

[edit]In cartography, several named map projections, including the Mercator projection and the stereographic projection are conformal. The preservation of compass directions makes them useful in marine navigation.

Physics and engineering

[edit]Conformal mappings are invaluable for solving problems in engineering and physics that can be expressed in terms of functions of a complex variable yet exhibit inconvenient geometries. By choosing an appropriate mapping, the analyst can transform the inconvenient geometry into a much more convenient one. For example, one may wish to calculate the electric field, , arising from a point charge located near the corner of two conducting planes separated by a certain angle (where is the complex coordinate of a point in 2-space). This problem per se is quite clumsy to solve in closed form. However, by employing a very simple conformal mapping, the inconvenient angle is mapped to one of precisely radians, meaning that the corner of two planes is transformed to a straight line. In this new domain, the problem (that of calculating the electric field impressed by a point charge located near a conducting wall) is quite easy to solve. The solution is obtained in this domain, , and then mapped back to the original domain by noting that was obtained as a function (viz., the composition of and ) of , whence can be viewed as , which is a function of , the original coordinate basis. Note that this application is not a contradiction to the fact that conformal mappings preserve angles, they do so only for points in the interior of their domain, and not at the boundary. Another example is the application of conformal mapping technique for solving the boundary value problem of liquid sloshing in tanks.[19]

If a function is harmonic (that is, it satisfies Laplace's equation ) over a plane domain (which is two-dimensional), and is transformed via a conformal map to another plane domain, the transformation is also harmonic. For this reason, any function which is defined by a potential can be transformed by a conformal map and still remain governed by a potential. Examples in physics of equations defined by a potential include the electromagnetic field, the gravitational field, and, in fluid dynamics, potential flow, which is an approximation to fluid flow assuming constant density, zero viscosity, and irrotational flow. One example of a fluid dynamic application of a conformal map is the Joukowsky transform that can be used to examine the field of flow around a Joukowsky airfoil.

Conformal maps are also valuable in solving nonlinear partial differential equations in some specific geometries. Such analytic solutions provide a useful check on the accuracy of numerical simulations of the governing equation. For example, in the case of very viscous free-surface flow around a semi-infinite wall, the domain can be mapped to a half-plane in which the solution is one-dimensional and straightforward to calculate.[20]

For discrete systems, Noury and Yang presented a way to convert discrete systems root locus into continuous root locus through a well-known conformal mapping in geometry (aka inversion mapping).[21]

Maxwell's equations

[edit]Maxwell's equations are preserved by Lorentz transformations which form a group including circular and hyperbolic rotations. The latter are sometimes called Lorentz boosts to distinguish them from circular rotations. All these transformations are conformal since hyperbolic rotations preserve hyperbolic angle, (called rapidity) and the other rotations preserve circular angle. The introduction of translations in the Poincaré group again preserves angles.

A larger group of conformal maps for relating solutions of Maxwell's equations was identified by Ebenezer Cunningham (1908) and Harry Bateman (1910). Their training at Cambridge University had given them facility with the method of image charges and associated methods of images for spheres and inversion. As recounted by Andrew Warwick (2003) Masters of Theory: [22]

- Each four-dimensional solution could be inverted in a four-dimensional hyper-sphere of pseudo-radius in order to produce a new solution.

Warwick highlights this "new theorem of relativity" as a Cambridge response to Einstein, and as founded on exercises using the method of inversion, such as found in James Hopwood Jeans textbook Mathematical Theory of Electricity and Magnetism.

General relativity

[edit]In general relativity, conformal maps are the simplest and thus most common type of causal transformations. Physically, these describe different universes in which all the same events and interactions are still (causally) possible, but a new additional force is necessary to affect this (that is, replication of all the same trajectories would necessitate departures from geodesic motion because the metric tensor is different). It is often used to try to make models amenable to extension beyond curvature singularities, for example to permit description of the universe even before the Big Bang.

See also

[edit]- Biholomorphic map

- Carathéodory's theorem – A conformal map extends continuously to the boundary

- Penrose diagram

- Schwarz–Christoffel mapping – a conformal transformation of the upper half-plane onto the interior of a simple polygon

- Special linear group – transformations that preserve volume (as opposed to angles) and orientation

References

[edit]- ^ Blair, David (2000-08-17). Inversion Theory and Conformal Mapping. The Student Mathematical Library. Vol. 9. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society. doi:10.1090/stml/009. ISBN 978-0-8218-2636-2. S2CID 118752074.

- ^ Richard M. Timoney (2004), Riemann mapping theorem from Trinity College Dublin

- ^

Geometry/Unified Angles at Wikibooks

Geometry/Unified Angles at Wikibooks

- ^ Tsurusaburo Takasu (1941) Gemeinsame Behandlungsweise der elliptischen konformen, hyperbolischen konformen und parabolischen konformen Differentialgeometrie, 2, Proceedings of the Imperial Academy 17(8): 330–8, link from Project Euclid, MR 0014282

- ^ Selig, Michael S.; Maughmer, Mark D. (1992-05-01). "Multipoint inverse airfoil design method based on conformal mapping". AIAA Journal. 30 (5): 1162–1170. Bibcode:1992AIAAJ..30.1162S. doi:10.2514/3.11046. ISSN 0001-1452.

- ^ Cortijo, Vanessa; Alonso, Elena R.; Mata, Santiago; Alonso, José L. (2018-01-18). "Conformational Map of Phenolic Acids". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 122 (2): 646–651. Bibcode:2018JPCA..122..646C. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.7b08882. ISSN 1520-5215. PMID 29215883.

- ^ "Properties of Conformal Mapping".

- ^ "7.1 GENETIC MAPS COME IN VARIOUS FORMS". www.informatics.jax.org. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Alim, Karen; Armon, Shahaf; Shraiman, Boris I.; Boudaoud, Arezki (2016). "Leaf growth is conformal". Physical Biology. 13 (5) 05LT01. arXiv:1611.07032. Bibcode:2016PhBio..13eLT01A. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/13/5/05lt01. PMID 27597439. S2CID 9351765. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ González-Matesanz, F. J.; Malpica, J. A. (2006-11-01). "Quasi-conformal mapping with genetic algorithms applied to coordinate transformations". Computers & Geosciences. 32 (9): 1432–1441. Bibcode:2006CG.....32.1432G. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2006.01.002. ISSN 0098-3004.

- ^ Berezovski, Volodymyr; Cherevko, Yevhen; Rýparová, Lenka (August 2019). "Conformal and Geodesic Mappings onto Some Special Spaces". Mathematics. 7 (8): 664. doi:10.3390/math7080664. hdl:11012/188984. ISSN 2227-7390.

- ^ Gronwall, T. H. (June 1920). "Conformal Mapping of a Family of Real Conics on Another". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 6 (6): 312–315. Bibcode:1920PNAS....6..312G. doi:10.1073/pnas.6.6.312. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1084530. PMID 16576504.

- ^ "Mapping in a sentence (esp. good sentence like quote, proverb...)". sentencedict.com. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ "EAP - Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Sciences – Publications". Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ López-Vázquez, Carlos (2012-01-01). "Positional Accuracy Improvement Using Empirical Analytical Functions". Cartography and Geographic Information Science. 39 (3): 133–139. Bibcode:2012CGISc..39..133L. doi:10.1559/15230406393133. ISSN 1523-0406. S2CID 123894885.

- ^ Calixto, Wesley Pacheco; Alvarenga, Bernardo; da Mota, Jesus Carlos; Brito, Leonardo da Cunha; Wu, Marcel; Alves, Aylton José; Neto, Luciano Martins; Antunes, Carlos F. R. Lemos (2011-02-15). "Electromagnetic Problems Solving by Conformal Mapping: A Mathematical Operator for Optimization". Mathematical Problems in Engineering. 2010 e742039. doi:10.1155/2010/742039. hdl:10316/110197. ISSN 1024-123X.

- ^ Leonhardt, Ulf (2006-06-23). "Optical Conformal Mapping". Science. 312 (5781): 1777–1780. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1777L. doi:10.1126/science.1126493. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16728596. S2CID 8334444.

- ^ Singh, Arun K.; Auton, Gregory; Hill, Ernie; Song, Aimin (2018-07-01). "Estimation of intrinsic and extrinsic capacitances of graphene self-switching diode using conformal mapping technique". 2D Materials. 5 (3): 035023. Bibcode:2018TDM.....5c5023S. doi:10.1088/2053-1583/aac133. ISSN 2053-1583. S2CID 117531045.

- ^ Kolaei, Amir; Rakheja, Subhash; Richard, Marc J. (2014-01-06). "Range of applicability of the linear fluid slosh theory for predicting transient lateral slosh and roll stability of tank vehicles". Journal of Sound and Vibration. 333 (1): 263–282. Bibcode:2014JSV...333..263K. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2013.09.002.

- ^ Hinton, Edward; Hogg, Andrew; Huppert, Herbert (2020). "Shallow free-surface Stokes flow around a corner". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 378 (2174). Bibcode:2020RSPTA.37890515H. doi:10.1098/rsta.2019.0515. PMC 7287310. PMID 32507085.

- ^ Noury, Keyvan; Yang, Bingen (2020). "A Pseudo S-plane Mapping of Z-plane Root Locus". ASME 2020 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. doi:10.1115/IMECE2020-23096. ISBN 978-0-7918-8454-6. S2CID 234582511.

- ^ Warwick, Andrew (2003). Masters of theory: Cambridge and the rise of mathematical physics. University of Chicago Press. pp. 404–424. ISBN 978-0-226-87375-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Ahlfors, Lars V. (1973), Conformal invariants: topics in geometric function theory, New York: McGraw–Hill Book Co., MR 0357743

- Constantin Carathéodory (1932) Conformal Representation, Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics and Physics

- Chanson, H. (2009), Applied Hydrodynamics: An Introduction to Ideal and Real Fluid Flows, CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Leiden, The Netherlands, 478 pages, ISBN 978-0-415-49271-3

- Churchill, Ruel V. (1974), Complex Variables and Applications, New York: McGraw–Hill Book Co., ISBN 978-0-07-010855-4

- E.P. Dolzhenko (2001) [1994], "Conformal mapping", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- Rudin, Walter (1987), Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.), New York: McGraw–Hill Book Co., ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1, MR 0924157

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Conformal Mapping". MathWorld.

External links

[edit]- Interactive visualizations of many conformal maps

- Conformal Maps by Michael Trott, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Conformal Mapping images of current flow in different geometries without and with magnetic field by Gerhard Brunthaler.

- Conformal Transformation: from Circle to Square.

- Online Conformal Map Grapher.

- Joukowski Transform Interactive WebApp

Conformal map

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Properties

Formal Definition

In mathematics, a conformal map is a diffeomorphism between Riemannian manifolds that locally preserves angles between tangent vectors. More precisely, is conformal if there exists a positive smooth function such that for every point and tangent vectors , This condition ensures that the inner product induced by the pushforward of the metric on is a positive scalar multiple of the original metric on , thereby scaling lengths by at each point while preserving the angles between them.[6] In the special case of Euclidean spaces and equipped with the standard Euclidean metrics, a differentiable map (with ) is conformal at a point if its Jacobian matrix satisfies for some scalar , where is the identity matrix. This condition implies that represents a similarity transformation—specifically, a scaling by composed with an orthogonal transformation—thus preserving angles between tangent vectors at .[7] Unlike isometries, which are diffeomorphisms preserving both angles and lengths exactly (corresponding to ), conformal maps allow the scaling factor to vary with position, thereby distorting distances by a local factor while maintaining angular fidelity. This distinction highlights conformal maps as a broader class of angle-preserving transformations, generalizing isometries by incorporating position-dependent scalings.[6] The term "conformal" derives from the Latin conformis, meaning "having the same shape" or "similar in form," reflecting the preservation of local shapes via angles in these mappings.[8]Key Properties

Conformal maps preserve the magnitude of angles between tangent vectors. They preserve orientation if the orthogonal transformation has determinant +1 (a rotation), meaning they map positively oriented bases to positively oriented bases; if (a reflection), the map reverses orientation. This follows from the local form of the differential , where is an orthogonal transformation with determinant , determining the orientation preservation or reversal.[9] Locally, at each point p in the domain, a conformal map behaves like a similarity transformation: the differential df_p scales lengths by the positive factor |μ(p)| and applies an orthogonal transformation, preserving shapes of infinitesimal figures up to scaling and rotation (or reflection if orientation-reversing). This local similarity ensures that angles between tangent vectors are preserved in magnitude, though the sign may flip with orientation reversal. Conformal maps cannot be constant on any open set, as constancy would imply df_p = 0, violating the non-vanishing scaling condition μ(p) ≠ 0.[9] The composition of two conformal maps is again conformal, with the scaling factor satisfying the chain rule ; this multiplicative property extends the local similarities under composition.[9] Liouville's theorem establishes uniqueness in global settings: any conformal map from the entire Euclidean space (n \geq 2) to itself must be an affine transformation, specifically a composition of translations, rotations, scalings, and possibly reflections, with no other possibilities due to the rigidity imposed by the conformality condition everywhere.[9]Conformal Mappings in Two Dimensions

Complex Analytic Functions

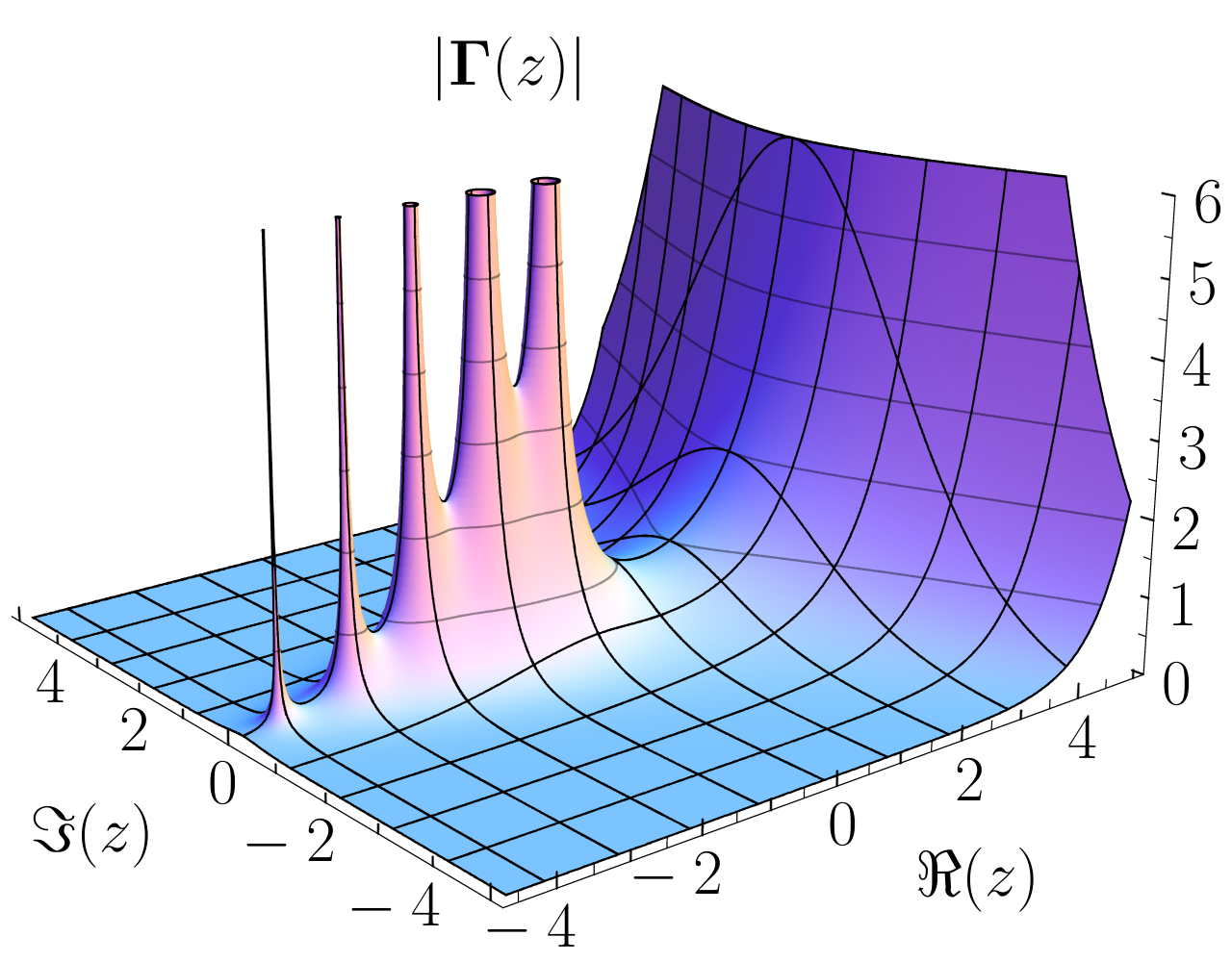

In the context of two-dimensional domains, a mapping , where is an open set, is conformal at every point in if and only if is holomorphic on and its derivative satisfies for all .[10] This equivalence establishes that conformality in the plane is intrinsically tied to the properties of complex analytic functions, excluding points where the derivative vanishes, as those would introduce singularities or critical points that distort the local similarity.[11] The holomorphy condition manifests through the Cauchy-Riemann equations, which for are given by These equations ensure that the Jacobian matrix of the transformation is a composition of rotation and uniform scaling, preserving oriented angles locally while allowing for magnification.[1] When combined with the non-vanishing derivative, , the mapping remains invertible in a neighborhood of each point, reinforcing its conformal nature.[12] A key implication for the global behavior of such mappings arises from the open mapping theorem, which states that any non-constant holomorphic function maps open sets to open sets. This property guarantees that conformal maps between domains preserve topological openness, facilitating the study of how simply connected regions can be transformed without collapsing interiors.[13] Illustrative examples include the exponential map , which conformally maps the horizontal strip onto the open upper half-plane , demonstrating how it transforms linear strips into angular sectors.[14] Conversely, the principal branch of the logarithm serves as its inverse, mapping the slit plane conformally back to the strip, highlighting the utility of these functions in bridging linear and polar geometries. For punctured annuli, such as , the logarithm maps to a vertical strip .[1] This profound link between conformal mappings and holomorphic functions was formalized by Bernhard Riemann in his 1851 habilitation thesis, where he demonstrated the existence of conformal maps between simply connected domains via analytic continuation, profoundly influencing the development of modern complex analysis.[15]Angle Preservation

A conformal mapping preserves oriented angles, meaning that the angle between two smooth curves intersecting at a point in the domain is mapped to an angle of the same magnitude and sense (direction of rotation, such as counterclockwise or clockwise) in the image. This property arises because a holomorphic function with non-zero derivative at the point acts locally as multiplication by a complex number , which scales by and rotates by , thereby maintaining the relative orientation of tangent vectors.[16][17] Unoriented angles, which disregard the sense and focus solely on magnitude, are also preserved under conformal mappings, as the absolute value of the angle between curves remains unchanged. Directed angles, which incorporate both magnitude and sense, distinguish conformal maps from anti-conformal maps; the latter, such as complex conjugation , preserve angle magnitudes but reverse the sense, turning counterclockwise angles into clockwise ones and vice versa.[16][18] Geometrically, this angle preservation implies that infinitesimal triangles near the point are mapped to similar triangles in the image plane, scaled and rotated but without shearing or distortion of shape. For visualization, consider two curves intersecting at a 60° oriented angle in the domain; under a conformal map, their images intersect at a 60° oriented angle, preserving both the measure and the direction of rotation from one tangent to the other.[2][16] An illustrative example is the squaring map , which is conformal everywhere except at the origin where ; at the origin, angles are doubled (e.g., a 30° angle maps to 60°), but locally away from the origin, oriented angles are preserved due to the non-zero derivative.[19][2]Global Mappings on the Riemann Sphere

The Riemann sphere, denoted , serves as a universal domain in the theory of conformal mappings, where the uniformization theorem states that every simply connected Riemann surface is biholomorphic to the Riemann sphere (elliptic case), the complex plane (parabolic case), or the unit disk (hyperbolic case).[20] This theorem, proved independently by Henri Poincaré and Paul Koebe in 1907, underscores the sphere's role in classifying conformal structures globally on Riemann surfaces.[21] The automorphisms of the Riemann sphere, which are bijective conformal mappings from to itself, are precisely the Möbius transformations of the form where and .[22] These transformations form the group and act transitively on the sphere, preserving generalized circles (circles or straight lines in the plane) and angles globally, thus maintaining conformal structure across the entire compactified plane.[23] Unlike local conformal maps, Möbius transformations provide a complete atlas for the sphere, enabling uniform treatment of points at infinity. A key example of a global conformal mapping involving the Riemann sphere is the stereographic projection, which bijectively maps the unit sphere (removing the north pole ) to the complex plane , extended to a homeomorphism by sending to .[24] This projection is conformal everywhere except at the north pole, where it is defined by continuity but not differentiably, and its inverse shares the same property at the south pole; it preserves angles and circles, illustrating how the sphere uniformizes the plane topologically.[24] In modern extensions, quasiconformal maps generalize these strict conformal bijections for near-conformal cases in computational geometry, where solutions to the Beltrami equation (with ) approximate global mappings on the Riemann sphere while controlling distortion.[25] These maps, useful for mesh parameterization and surface uniformization, relax the holomorphicity condition to allow bounded quasiconformal dilatation, bridging classical theory with numerical applications.[26]Conformal Mappings in Higher Dimensions

Riemannian Manifolds

A conformal map between two Riemannian manifolds and is a smooth map such that for every point and tangent vectors , the metric pulls back via the differential to a scalar multiple of , specifically , where is a positive smooth function known as the conformal factor. This condition ensures that preserves angles between curves up to the scaling by , but generally distorts lengths. In the special case where , the map is an isometry.[27] Conformal maps on Riemannian manifolds are closely related to Weyl rescalings of the metric tensor. A Weyl rescaling transforms the metric to a conformally equivalent metric , where is a smooth function; this preserves the conformal class of the metric, meaning angles are unchanged while lengths are scaled by .[28] Such rescalings correspond to the identity map being conformal with , and they form the foundation for studying conformal structures on manifolds, where the geometry is defined up to local rescalings.[29] Under a conformal transformation, the Weyl tensor, which encodes the "angle part" or traceless conformally invariant component of the Riemann curvature tensor, remains unchanged.[30] In contrast, the scalar curvature transforms non-trivially: for a rescaling on an -dimensional manifold with , the transformed scalar curvature is , where is the Laplace-Beltrami operator; thus, the leading term scales inversely with the square of the conformal factor. This transformation law highlights how conformal maps distort size-related curvatures while preserving directional aspects. Prominent examples include the stereographic projection from the -sphere (with the round metric) to , which is conformal with a position-dependent factor (for the inverse map from to ; the projection has the reciprocal), embedding the sphere minus a point into Euclidean space while preserving angles.[31] Another key example is the conformal compactification of Minkowski spacetime, which embeds the non-compact Lorentzian manifold into the compact Einstein static universe via a Weyl rescaling that adds a conformal boundary at infinity, facilitating the study of asymptotic properties.[32] Conformal geometry emerges as a subfield of differential geometry focused on structures invariant under such maps, particularly through Weyl structures equipped with Cartan connections. These connections generalize the Levi-Civita connection to account for the scale ambiguity in conformal classes, providing a Cartan geometry modeled on the Möbius group acting on the sphere; post-2000 developments have emphasized their role in higher-dimensional conformal invariants and tractor bundles for global analysis.[33]Euclidean Spaces

In Euclidean spaces of dimension , conformal maps preserve angles and are significantly more rigid than in two dimensions, forming a finite-dimensional group known as the conformal group . This group is generated by translations, rotations, dilations, and special conformal transformations (inversions), and is isomorphic to the orthogonal group . The dimension of the conformal group is , reflecting the number of independent generators: for translations, for rotations, 1 for dilations, and for special conformal transformations.[34] Explicit forms of these transformations include similarities, which combine rigid motions (translations and rotations) with uniform scaling by a factor , given by where is an orthogonal matrix and . Special conformal transformations extend this via inversions with respect to spheres; for the unit sphere centered at the origin, the inversion is , which can be composed with similarities to generalize to arbitrary spheres. These inversions are orientation-reversing, but composing with a reflection (e.g., ) yields orientation-preserving variants. The full group acts transitively on , mapping any point to any other while preserving the conformal structure. A notable example is the Kelvin transform, defined for a function harmonic on a domain () as . This is the composition of inversion in the unit sphere with a radial scaling factor to preserve harmonicity: if is harmonic, then so is on the inverted domain . The Kelvin transform is its own inverse and plays a key role in potential theory by relating solutions near the origin to those at infinity, facilitating the analysis of singularities and boundary value problems for the Laplace equation.[35] Liouville's theorem provides a rigidity result: any conformal map on a connected open set () is a Möbius transformation, i.e., a composition of the above generators. A generalization states that bounded entire conformal maps on () are constant, as non-constant Möbius transformations are unbounded due to poles or growth at infinity.[36] Inversions exemplify the group's action on geometry: the map sends generalized circles—lines or spheres in —to other generalized circles, preserving their intersections and enabling symmetry in potential theory applications like solving exterior Dirichlet problems by transforming them to interior ones. In higher dimensions, quasiconformal maps generalize conformal maps by allowing bounded distortion, defined via the quasiconformal constant where the supremum of the ratio of the maximum to minimum stretch is . Computational methods in geometry compute such maps for applications including 3D surface registration and image retargeting in computer graphics, preserving topology while minimizing distortion (e.g., in brain MRI alignment or bijective 3D mappings).[35][37]Applications

Cartography

In cartography, conformal map projections are essential for preserving local shapes and angles, making them ideal for navigation and thematic mapping where directional accuracy is paramount. These projections transform the curved surface of the Earth onto a flat plane while maintaining the property that angles between curves remain unchanged, allowing compass bearings to be plotted directly.[38] This angle-preserving quality stems from the conformal nature of the mapping, ensuring that small-scale features like coastlines appear undistorted in orientation.[39] The Mercator projection, introduced by Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569, exemplifies a cylindrical conformal projection designed for maritime navigation. It renders rhumb lines—constant bearing paths—as straight lines, facilitating course plotting. The projection's formulas are and , where is longitude and is latitude in radians; meridians become equally spaced vertical lines, while parallels are horizontal but increasingly spaced toward the poles, leading to infinite scale distortion at the poles, which excludes polar regions from practical mapping.[40][41] Historically, Mercator's chart supported European exploration and trade by prioritizing equatorial and mid-latitude accuracy, where most shipping occurred.[41] Another key conformal projection is the stereographic, which projects the sphere onto a plane from a point on the sphere, typically the north pole for polar maps. This azimuthal projection preserves circles on the sphere as circles or straight lines on the plane and is conformal, maintaining angles for accurate depiction of polar regions. It is widely used in meteorological and aeronautical charts for high-latitude areas, such as Antarctic expeditions or Arctic monitoring, due to minimal distortion near the projection center.[42][43] For mid-latitude regions spanning east-west extents, the Lambert conformal conic projection, developed by Johann Heinrich Lambert in 1772, offers a balanced alternative. This conic projection touches the globe along one or two standard parallels, minimizing angular distortion in zones like North America or Europe. It is standard for national topographic maps in the contiguous United States, where it supports aviation and regional planning by preserving shapes over large areas without the extreme polar exaggeration of cylindrical projections.[44] Despite their strengths, conformal projections involve trade-offs: while shapes and angles are preserved locally, areas are distorted, particularly at higher latitudes. For instance, on the Mercator projection, Greenland appears vastly larger than Africa—roughly 14 times its actual size—exaggerating the relative scale of polar landmasses and leading to perceptual biases in global comparisons.[45][46] In modern geographic information systems (GIS), the Web Mercator variant— a spherical approximation of the original—powers online platforms like Google Maps, enabling seamless zooming and panning across web browsers while retaining conformal properties for urban and regional navigation.[47][48] However, post-2010 scholarship in decolonizing cartography critiques such projections for perpetuating colonial legacies, as their distortions amplify the apparent importance of northern hemispheres and European-centric views, marginalizing equatorial and southern regions in visual representations of global power dynamics.[49][50]Electromagnetism

In two-dimensional electrostatics, Maxwell's equations in charge-free regions simplify to the divergence-free and curl-free conditions on the electric field , and , which imply that the electric potential satisfies Laplace's equation .[51] This harmonic property allows solutions via conformal mappings, as the real part of a holomorphic function is harmonic, preserving the equation under such transformations.[51] The complex potential , where , is the electric potential, and is the stream function (orthogonal to equipotentials), provides a holomorphic representation for solving boundary value problems, with , where is the direction tangent to the streamlines.[51] The method of images, extended through circle inversions—a conformal transformation mapping circles to lines or circles—facilitates solving boundary conditions for conducting surfaces like spheres or cylinders by placing image charges at inverted points, ensuring the potential vanishes on the boundary.[52] For instance, a point charge outside a grounded conducting sphere uses inversion in the sphere's surface to yield an image charge inside, simplifying the potential calculation while maintaining conformal properties.[52] Representative examples include the electrostatic field around a conducting cylinder, analogous to inviscid fluid flow past a cylinder via the Joukowski transformation , which maps a circle to an airfoil-like shape and computes the potential for uniform external fields perturbed by the conductor.[53] In engineering electromagnetics, conformal mappings determine the capacitance per unit length of transmission lines with arbitrary cross-sections, such as coplanar strips, by transforming the geometry to a parallel-plate equivalent, yielding quasi-static parameters like characteristic impedance.[54] For irregular boundaries, such as polygonal conductors, the Schwarz-Christoffel mapping conformally transforms the upper half-plane to the polygonal region, enabling exact solutions to Laplace's equation via integrals that parameterize vertex angles, thus computing fields in complex electrostatic configurations like multi-conductor systems.[55] In four-dimensional Minkowski spacetime, conformal transformations preserve the structure of Maxwell's equations due to their invariance under angle-preserving scalings, specifically maintaining null geodesics that correspond to light rays and electromagnetic wave propagation paths.[56] Historically, Riemann's foundational work on conformal mappings in the mid-19th century influenced applications to electromagnetism, with physicists like Gustav Kirchhoff employing complex potentials and analogies to steady currents in conductors, treating electrical conduction as a two-dimensional potential flow problem solvable by holomorphic functions.[57]General Relativity

In general relativity, the conformal structure of spacetime is fundamental to understanding causality and the propagation of light. The metric tensor is defined up to a Weyl rescaling , where is a positive scalar function, which preserves angles and the causal structure, particularly the light cones that define null geodesics. This invariance under rescaling highlights how conformal maps maintain the physical distinction between timelike, spacelike, and null paths without altering the overall geometry's conformal class. Penrose diagrams provide a powerful visualization tool by employing conformal compactification, transforming the infinite spacetime into a finite diagram while preserving its causal relations. This technique maps the unphysical infinity to boundaries, allowing the depiction of asymptotic regions, singularities, and horizons in a compact form, such as the diamond-shaped diagram for Minkowski spacetime. By choosing a suitable conformal factor, the entire causal structure, including infinite distances, is represented within a bounded region, facilitating analysis of global properties like the approach to future null infinity.[58] The Weyl tensor , the trace-free part of the Riemann curvature tensor, quantifies the nonconformal curvature that cannot be eliminated by local coordinate choices or rescalings. It measures tidal forces and gravitational waves, vanishing in spacetimes that are locally conformally flat, where the metric can be written as with the Minkowski metric. In Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) models, the Weyl tensor vanishes identically due to spatial homogeneity and isotropy, rendering these cosmologies conformally flat; this is particularly evident in the radiation-dominated era, where the scale factor in conformal time , aligning the metric directly with a flat conformal structure.[59] Applications of conformal maps in general relativity extend to black hole physics and holography. Black hole horizons serve as conformal boundaries in the compactified spacetime, where the conformal factor brings the event horizon to a finite location in Penrose diagrams, enabling study of their causal isolation and thermodynamic properties.[60] In the AdS/CFT correspondence, the conformal structure of the anti-de Sitter (AdS) boundary matches that of a conformal field theory (CFT), providing a holographic dual where bulk gravitational dynamics encode CFT correlators, linking quantum gravity to boundary conformal invariance. Recent developments in the 2020s have leveraged the conformal bootstrap to impose constraints on quantum gravity theories. The bootstrap approach uses consistency conditions on CFT data to bound operator dimensions and OPE coefficients, revealing tensions with semiclassical gravity in AdS₃, such as the absence of pure Einstein gravity as a consistent quantum theory below certain central charge thresholds. These methods, combined with analytic bootstrap techniques, offer non-perturbative insights into swampland conjectures and the emergence of spacetime from CFTs, advancing our understanding of quantum gravity constraints.Engineering

In aerodynamics, conformal mappings enable the analysis of fluid flow around complex shapes by transforming simpler geometries, such as circles, into airfoil profiles. The Joukowski transformation, defined by where is a parameter controlling the airfoil thickness, maps the exterior of a circle in the -plane to the exterior of a symmetric airfoil in the -plane, facilitating the solution of potential flow problems. This approach preserves angles and allows the use of known solutions for circular cylinders to compute velocity fields around airfoils. Lift generation is quantified via the Kutta-Joukowski theorem, which states that the lift per unit span , where is fluid density, is freestream velocity, and is circulation determined by the mapping and the Kutta condition at the trailing edge.[62][63] Conformal mappings also solve heat conduction problems governed by Laplace's equation in irregular domains by transforming them into regular shapes where analytical solutions are straightforward. For instance, in steady-state heat transfer across thermal barriers like slots or insulated regions, the Schwarz-Christoffel mapping converts polygonal boundaries to the upper half-plane, enabling harmonic function solutions for temperature distributions.[64] This method computes isotherms and heat flux without numerical approximation, as demonstrated in analyses of conduction through narrow gaps where boundary conditions specify fixed temperatures.[65] Such transformations maintain the harmonic property of solutions to Laplace's equation , ensuring angle preservation at interfaces.[66] In numerical methods for engineering simulations, conformal mappings generate meshes that minimize distortion in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and finite element analysis (FEA). By orthogonally mapping complex domains to computational planes, these techniques produce grids with low skewness, improving convergence and accuracy in solving partial differential equations over irregular geometries.[67] For CFD applications, such as turbine blade flows, conformal O-grids wrap around airfoils while preserving flow angles, reducing element aspect ratios compared to algebraic methods.[68] In FEA for structural heat transfer, quasiconformal extensions allow controlled distortion for three-dimensional meshes, balancing conformality with adaptability.[69] Electrical engineering employs conformal mappings in antenna design to preserve radiation patterns during shape optimization. Quasi-conformal transformations modify isotropic radiators into curved surfaces, such as cylindrical arrays, while maintaining omnidirectional far-field patterns by controlling local angle distortions.[70] This is particularly useful for conformal phased arrays on vehicles, where mappings ensure uniform beam scanning without grating lobes.[71] Modern computer-aided design (CAD) tools integrate quasiconformal mappings for mesh deformation and texture parameterization in graphics applications, including Blender since version 2.73 (2015). These mappings minimize angular distortion during UV unwrapping of 3D models, enabling seamless texturing for engineering visualizations like product renders.[72] In control systems, the bilinear transformation approximates continuous-time designs in discrete implementations, preserving stability regions via its conformal properties in the s-z plane.[73]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/conformal

- https://www.grc.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/www/k-12/airplane/map.html