Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Porphyrin

View on Wikipedia

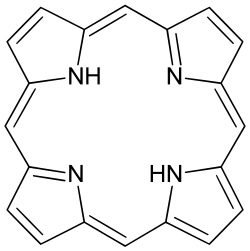

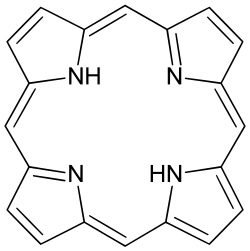

Porphyrins (/ˈpɔːrfərɪns/ POR-fər-ins) are heterocyclic, macrocyclic, organic compounds, composed of four modified pyrrole subunits interconnected at their α carbon atoms via methine bridges (=CH−). In vertebrates, an essential member of the porphyrin group is heme, which is a component of hemoproteins, whose functions include carrying oxygen in the bloodstream. In plants, an essential porphyrin derivative is chlorophyll, which is involved in light harvesting and electron transfer in photosynthesis.

The parent of porphyrins is porphine, a rare chemical compound of exclusively theoretical interest. Substituted porphines are called porphyrins.[1] With a total of 26 π-electrons the porphyrin ring structure is a coordinated aromatic system.[2] One result of the large conjugated system is that porphyrins absorb strongly in the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum, i.e. they are deeply colored. The name "porphyrin" derives from Greek πορφύρα (porphyra) 'purple'.[3]

Structure

[edit]Porphyrin complexes consist of a square planar MN4 core. The periphery of the porphyrins, consisting of sp2-hybridized carbons, generally display small deviations from planarity. "Ruffled" or saddle-shaped porphyrins is attributed to interactions of the system with its environment.[4] Additionally, the metal is often not centered in the N4 plane.[5] For free porphyrins, the two pyrrole protons are mutually trans and project out of the N4 plane.[6] These nonplanar distortions are associated with altered chemical and physical properties. Chlorophyll-rings are more distinctly nonplanar, but they are more saturated than porphyrins.[7]

Complexes of porphyrins

[edit]Concomitant with the displacement of two N-H protons, porphyrins bind metal ions in the N4 "pocket". The metal ion usually has a charge of 2+ or 3+. A schematic equation for these syntheses is shown, where M = metal ion and L = a ligand:

- H2porphyrin + [MLn]2+ → M(porphyrinate)Ln−4 + 4 L + 2 H+

- Representative porphyrins and derivatives

-

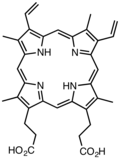

Derivatives of protoporphyrin IX are common in nature, the precursor to hemes.

-

Octaethylporphyrin (H2OEP) is a synthetic analogue of protoporphyrin IX. Unlike the natural porphyrin ligands, OEP2− is highly symmetrical.

-

Tetraphenylporphyrin (H2TPP)is another synthetic analogue of protoporphyrin IX. Unlike the natural porphyrin ligands, TPP2− is highly symmetrical. Another difference is that its methyne centers are occupied by phenyl groups.

-

Simplified view of heme, a complex of a protoporphyrin IX

-

A nanoring of 40 porphyrin molecules, model

-

A nanoring of 40 porphyrin molecules, STM image

Ancient porphyrins

[edit]A geoporphyrin, also known as a petroporphyrin, is a porphyrin of geologic origin.[8] They can occur in crude oil, oil shale, coal, or sedimentary rocks.[8][9] Abelsonite is possibly the only geoporphyrin mineral, as it is rare for porphyrins to occur in isolation and form crystals.[10]

The field of organic geochemistry had its origins in the isolation of porphyrins from petroleum. These findings helped establish the biological origins of petroleum.[11][12] Petroleum is sometimes "fingerprinted" by analysis of trace amounts of nickel and vanadyl porphyrins. Metalloporphyrins in general are highly stable organic compounds, and the detailed structures of the extracted derivatives made clear that they originated from chlorophyll.

Biosynthesis

[edit]In non-photosynthetic eukaryotes such as animals, insects, fungi, and protozoa, as well as the α-proteobacteria group of bacteria, the committed step for porphyrin biosynthesis is the formation of δ-aminolevulinic acid (δ-ALA, 5-ALA or dALA) by the reaction of the amino acid glycine with succinyl-CoA from the citric acid cycle. In plants, algae, bacteria (except for the α-proteobacteria group) and archaea, it is produced from glutamic acid via glutamyl-tRNA and glutamate-1-semialdehyde. The enzymes involved in this pathway are glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, glutamyl-tRNA reductase, and glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2,1-aminomutase. This pathway is known as the C5 or Beale pathway.

Two molecules of dALA are then combined by porphobilinogen synthase to give porphobilinogen (PBG), which contains a pyrrole ring. Four PBGs are then combined through deamination into hydroxymethyl bilane (HMB), which is hydrolysed to form the circular tetrapyrrole uroporphyrinogen III. This molecule undergoes a number of further modifications. Intermediates are used in different species to form particular substances, but, in humans, the main end-product protoporphyrin IX is combined with iron to form heme. Bile pigments are the breakdown products of heme.

The following scheme summarizes the biosynthesis of porphyrins, with references by EC number and the OMIM database. The porphyria associated with the deficiency of each enzyme is also shown:

Laboratory synthesis

[edit]

A common synthesis for porphyrins is the Rothemund reaction, first reported in 1936,[13][14] which is also the basis for more recent methods described by Adler and Longo.[15] The general scheme is a condensation and oxidation process starting with pyrrole and an aldehyde.

Potential applications

[edit]Photodynamic therapy

[edit]Porphyrins have been evaluated in the context of photodynamic therapy (PDT) since they strongly absorb light, which is then converted to heat in the illuminated areas.[16] This technique has been applied in macular degeneration using verteporfin.[17]

PDT is considered a noninvasive cancer treatment, involving the interaction between light of a determined frequency, a photo-sensitizer, and oxygen. This interaction produces the formation of a highly reactive oxygen species (ROS), usually singlet oxygen, as well as superoxide anion, free hydroxyl radical, or hydrogen peroxide.[18] These high reactive oxygen species react with susceptible cellular organic biomolecules such as; lipids, aromatic amino acids, and nucleic acid heterocyclic bases, to produce oxidative radicals that damage the cell, possibly inducing apoptosis or even necrosis.[19]

Molecular electronics and sensors

[edit]Porphyrin-based compounds are of interest as possible components of molecular electronics and photonics.[20] Synthetic porphyrin dyes have been incorporated in prototype dye-sensitized solar cells.[21][22]

Biological applications

[edit]Porphyrins have been investigated as possible anti-inflammatory agents[23] and evaluated on their anti-cancer and anti-oxidant activity.[24] Several porphyrin-peptide conjugates were found to have antiviral activity against HIV in vitro.[25]

Toxicology

[edit]Heme biosynthesis is used as biomarker in environmental toxicology studies. While excess production of porphyrins indicate organochlorine exposure, lead inhibits ALA dehydratase enzyme.[26]

Gallery

[edit]-

Lewis structure for meso-tetraphenylporphyrin

-

UV–vis readout for meso-tetraphenylporphyrin

-

Light-activated porphyrin. Monatomic oxygen. Cellular aging.

Related species

[edit]In nature

[edit]Several heterocycles related to porphyrins are found in nature, almost always bound to metal ions. These include

| N4-macrocycle | Cofactor name | metal | comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| chlorin | chlorophyll | magnesium | several versions of chlorophyll exist (sidechain; exception being chlorophyll c) |

| bacteriochlorin | bacteriochlorophyll (in part) | magnesium | several versions of bacteriochlorophyll exist (sidechain; some use a usual chlorin ring) |

| sirohydrochlorin (an isobacteriochlorin) | siroheme | iron | Important cofactor in sulfur assimilation |

| biosynthetic intermediate en route to cofactor F430 and B12 | |||

| corrin | vitamin B12 | cobalt | several variants of B12 exist (sidechain) |

| corphin | Cofactor F430 | nickel | highly reduced macrocycle |

Synthetic

[edit]A benzoporphyrin is a porphyrin with a benzene ring fused to one of the pyrrole units. e.g. verteporfin is a benzoporphyrin derivative.[27]

Non-natural porphyrin isomers

[edit]

The first synthetic porphyrin isomer was reported by Emanual Vogel and coworkers in 1986.[28] This isomer [18]porphyrin-(2.0.2.0) is named as porphycene, and the central N4 Cavity forms a rectangle shape as shown in figure.[29] Porphycenes showed interesting photophysical behavior and found versatile compound towards the photodynamic therapy.[30] This result was followed by the preparation of [18]porphyrin-(2.1.0.1), named it as corrphycene or porphycerin.[31] Other non-natural porphyrins include [18]porphyrin-(2.1.1.0) and [18]porphyrin-(3.0.1.0) or isoporphycene.[32] The N-confused porphyrins feature one of the pyrrolic subunits with the nitrogen atoms facing outwards from the core of the macrocycle.[33][34]

See also

[edit]- Porphyria – Metabolic disorders in which porphyrins build up in the body

- Heme – Chemical coordination complex of an iron ion chelated to a porphyrin

- Cytochrome P450 – A class of enzymes containing heme

- Chlorophyll – Closely related to porphyrin

- Corroles – A closely related class of molecules, including vitamin B12

- Cofactor F430 contains porphyrin.

- Phthalocyanine and tetrapyrazinoporphyrazine are nitrogen-substituted porphyrins.

- Tetraanthraporphyrin – Extended porphyrin

References

[edit]- ^ Zhang, Wei; Lai, Wenzhen; Cao, Rui (2017). "Energy-Related Small Molecule Activation Reactions: Oxygen Reduction and Hydrogen and Oxygen Evolution Reactions Catalyzed by Porphyrin- and Corrole-Based Systems". Chemical Reviews. 117 (4): 3717–3797. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00299. PMID 28222601.

- ^ Lash TD (2011). "Origin of aromatic character in porphyrinoid systems". Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 15 (11n12): 1093–1115. doi:10.1142/S1088424611004063.

- ^ Harper D, Buglione DC. "porphyria (n.)". The Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Senge MO, MacGowan SA, O'Brien JM (December 2015). "Conformational control of cofactors in nature - the influence of protein-induced macrocycle distortion on the biological function of tetrapyrroles". Chemical Communications. 51 (96): 17031–17063. doi:10.1039/C5CC06254C. hdl:2262/75305. PMID 26482230.

- ^ Walker FA, Simonis U (2011). "Iron Porphyrin Chemistry". Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc0104. ISBN 978-1-119-95143-8.

- ^ Jentzen W, Ma JG, Shelnutt JA (February 1998). "Conservation of the conformation of the porphyrin macrocycle in hemoproteins". Biophysical Journal. 74 (2 Pt 1): 753–763. Bibcode:1998BpJ....74..753J. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74000-7. PMC 1302556. PMID 9533688.

- ^ Senge MO, Ryan AA, Letchford KA, MacGowan SA, Mielke T (2014). "Chlorophylls, Symmetry, Chirality, and Photosynthesis". Symmetry. 6 (3): 781–843. Bibcode:2014Symm....6..781S. doi:10.3390/sym6030781. hdl:2262/73843.

- ^ a b Kadish KM, ed. (1999). The Porphyrin Handbook. Elsevier. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-12-393200-6.

- ^ Zhang B, Lash TD (September 2003). "Total synthesis of the porphyrin mineral abelsonite and related petroporphyrins with five-membered exocyclic rings". Tetrahedron Letters. 44 (39): 7253. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.08.007.

- ^ Mason GM, Trudell LG, Branthaver JF (1989). "Review of the stratigraphic distribution and diagenetic history of abelsonite". Organic Geochemistry. 14 (6): 585. Bibcode:1989OrGeo..14..585M. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(89)90038-7.

- ^ Kvenvolden, Keith A. (2006). "Organic geochemistry – A retrospective of its first 70 years". Organic Geochemistry. 37: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2005.09.001

- ^ Treibs, A.E. (1936). "Chlorophyll- und Häminderivate in organischen Mineralstoffen". Angewandte Chemie. 49: 682–686. doi:10.1002/ange.19360493803

- ^ Rothemund P (1936). "A New Porphyrin Synthesis. The Synthesis of Porphin". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 58 (4): 625–627. Bibcode:1936JAChS..58..625R. doi:10.1021/ja01295a027.

- ^ Rothemund P (1935). "Formation of Porphyrins from Pyrrole and Aldehydes". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 57 (10): 2010–2011. Bibcode:1935JAChS..57.2010R. doi:10.1021/ja01313a510.

- ^ Adler AD, Longo FR, Finarelli JD, Goldmacher J, Assour J, Korsakoff L (1967). "A simplified synthesis for meso-tetraphenylporphine". J. Org. Chem. 32 (2): 476. doi:10.1021/jo01288a053.

- ^ Giuntini F, Boyle R, Sibrian-Vazquez M, Vicente MG (2014). "Porphyrin conjugates for cancer therapy". In Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R (eds.). Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Vol. 27. pp. 303–416.

- ^ Wormald R, Evans J, Smeeth L, Henshaw K (July 2007). "Photodynamic therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3) CD002030. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002030.pub3. PMID 17636693.

- ^ Price M, Terlecky SR, Kessel D (2009). "A role for hydrogen peroxide in the pro-apoptotic effects of photodynamic therapy". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 85 (6): 1491–1496. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2009.00589.x. PMC 2783742. PMID 19659920.

- ^ Singh S, Aggarwal A, Bhupathiraju NV, Arianna G, Tiwari K, Drain CM (September 2015). "Glycosylated Porphyrins, Phthalocyanines, and Other Porphyrinoids for Diagnostics and Therapeutics". Chemical Reviews. 115 (18): 10261–10306. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00244. PMC 6011754. PMID 26317756.

- ^ Lewtak JP, Gryko DT (October 2012). "Synthesis of π-extended porphyrins via intramolecular oxidative coupling". Chemical Communications. 48 (81): 10069–10086. doi:10.1039/c2cc31279d. PMID 22649792.

- ^ Walter MG, Rudine AB, Wamser CC (2010). "Porphyrins and phthalocyanines in solar photovoltaic cells". Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 14 (9): 759–792. doi:10.1142/S1088424610002689.

- ^ Yella A, Lee HW, Tsao HN, Yi C, Chandiran AK, Nazeeruddin MK, et al. (November 2011). "Porphyrin-sensitized solar cells with cobalt (II/III)-based redox electrolyte exceed 12 percent efficiency". Science. 334 (6056): 629–634. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..629Y. doi:10.1126/science.1209688. PMID 22053043. S2CID 28058582.

- ^ Alonso-Castro AJ, Zapata-Morales JR, Hernández-Munive A, Campos-Xolalpa N, Pérez-Gutiérrez S, Pérez-González C (May 2015). "Synthesis, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of porphyrins". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 23 (10): 2529–2537. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2015.03.043. PMID 25863493.

- ^ Bajju GD, Ahmed A, Devi G (December 2019). "Synthesis and bioactivity of oxovanadium(IV)tetra(4-methoxyphenyl)porphyrinsalicylates". BMC Chemistry. 13 (1) 15. doi:10.1186/s13065-019-0523-9. PMC 6661832. PMID 31384764.

- ^ Mendonça DA, Bakker M, Cruz-Oliveira C, Neves V, Jiménez MA, Defaus S, et al. (June 2021). "Penetrating the Blood-Brain Barrier with New Peptide-Porphyrin Conjugates Having anti-HIV Activity". Bioconjugate Chemistry. 32 (6): 1067–1077. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.1c00123. PMC 8485325. PMID 34033716.

- ^ Walker CH, Silby RM, Hopkin SP, Peakall DB (2012). Principles of Ecotoxicology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4665-0260-4.

- ^ Scott LJ, Goa KL (February 2000). "Verteporfin". Drugs & Aging. 16 (2): 139–146, discussion 146–8. doi:10.2165/00002512-200016020-00005. PMID 10755329. S2CID 260491296.

- ^ Vogel E, Köcher M (March 1986). "Porphycene—a Novel Porphin Isomer". Angewandte Chemie. 25 (3): 257. doi:10.1002/anie.198602571.

- ^ Nagamaiah J, Dutta A, Pati NN, Sahoo S, Soman R, Panda PK (March 2022). "3,6,13,16-Tetrapropylporphycene: Rational Synthesis, Complexation, and Halogenation". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 87 (5): 2721–2729. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c02652. PMID 35061396. S2CID 246165814.

- ^ Dougherty TJ (2001). "Basic principles of photodynamic therapy". Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 5 (2): 105. doi:10.1002/jpp.328.

- ^ Vogel E, Guilard R (November 1993). "New Porphycene Ligands: Octaethyl- and Etioporphycene (OEPc and EtioPc)—Tetra- and Pentacoordinated Zinc Complexes of OEPc". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 32 (11): 1600. doi:10.1002/anie.199316001.

- ^ Vogel E, Scholz P, Demuth R, Erben C, Bröring M, Schmickler H, et al. (October 1999). "Isoporphycene: The Fourth Constitutional Isomer of Porphyrin with an N(4) Core-Occurrence of E/Z Isomerism". Angewandte Chemie. 38 (19): 2919–2923. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19991004)38:19<2919::AID-ANIE2919>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 10540393.

- ^ Hiroyuki F (1994). ""N-Confused Porphyrin": A New Isomer of Tetraphenylporphyrin". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 (2): 767. Bibcode:1994JAChS.116..767F. doi:10.1021/ja00081a047.

- ^ Chmielewski PJ, Latos-Grażyński L, Rachlewicz K, Glowiak T (18 April 1994). "Tetra-p-tolylporphyrin with an Inverted Pyrrole Ring: A Novel Isomer of Porphyrin". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 33 (7): 779. doi:10.1002/anie.199407791.

External links

[edit]Porphyrin

View on GrokipediaStructure and Properties

Core Structure

Porphyrin is a heterocyclic macrocycle composed of four pyrrole rings interconnected at their α-carbon atoms via four methine bridges (=CH-), forming a conjugated cyclic array.[6] The parent compound, known as porphine, has the molecular formula CHN and features a tetrapyrrolic core with 20 carbon atoms and 4 nitrogen atoms arranged in a nearly planar configuration.[6] In this structure, each pyrrole ring contributes two carbon atoms to the outer perimeter, while the methine bridges link them to create a 20-membered outer ring and a 16-membered inner ring; the nitrogen atoms bear hydrogen atoms (N-H bonds) directed toward the center, enabling potential coordination sites.[7] The conjugated π-electron system in porphine spans the macrocycle, delocalizing electrons across the alternating double bonds in the pyrrole units and methine bridges. This system contains 18 π-electrons, adhering to Hückel's rule (4n + 2, where n = 4), which imparts aromatic character and enhances the molecule's thermodynamic stability while modulating its reactivity, such as in electrophilic substitutions at the meso positions.[8] The planar geometry facilitates this delocalization, with the inner cavity allowing for interactions that underpin its role in metal complex formation.[7] Crystallographic analysis of porphine reveals a monoclinic crystal structure (space group P2/c) with key bond lengths reflecting the partial double-bond character due to conjugation: pyrrolic C-N bonds average approximately 1.37 Å, while ring C-C bonds are around 1.40 Å, and methine C-CH bonds measure about 1.37 Å.[9] These dimensions, determined from X-ray diffraction data, underscore the uniform electron distribution across the macrocycle, contributing to its rigidity and photochemical properties.[9]Substituent Variations

Porphyrins can be modified through substitution at the β-positions on the pyrrole rings (carbons 2, 3, 7, 8, 12, 13, 17, 18) or at the meso-positions on the methine bridges (carbons 5, 10, 15, 20), allowing for diverse structural variations while maintaining the core macrocycle.[10] These positions enable the attachment of alkyl, aryl, or functional groups that alter the molecule's overall properties without disrupting the conjugated π-system.[11] In naturally occurring porphyrins, such as protoporphyrin IX, substituents are primarily located at the β-positions, including four methyl groups, two vinyl groups, and two propionate groups, which contribute to its role in biological systems like heme.[12] This unsymmetrical β-substitution pattern distinguishes protoporphyrin IX from the unsubstituted porphine core and facilitates specific interactions in enzymatic environments.[13] Synthetic porphyrins often feature uniform substitutions for controlled reactivity; for example, meso-tetraphenylporphyrin (TPP) bears four phenyl groups at the meso-positions, enhancing synthetic accessibility and versatility in coordination studies.[14] Similarly, octaethylporphyrin (OEP) incorporates eight ethyl groups at the β-positions, providing a model for densely substituted systems closer to natural porphyrins in peripheral crowding.[15] Substituents significantly influence solubility, with hydrophilic groups like carboxylates in propionates improving aqueous solubility, while bulky aryl groups in TPP increase organic solvent solubility compared to β-alkyl variants.[11] They also affect stability, as sterically demanding meso-aryl substituents enhance thermal and oxidative stability by reducing macrocycle distortion.[16] Steric effects from meso-aryl groups, such as in TPP, prevent intermolecular aggregation through spatial hindrance, promoting monomeric behavior in solution. Historical nomenclature for substituted porphyrins, developed by Hans Fischer, uses Roman numerals (I–IV) to denote the four possible positional isomers of β-substituted patterns, ensuring unambiguous identification of stereochemical arrangements.[17] This system remains relevant for classifying complex natural and synthetic derivatives.Physical and Spectroscopic Properties

Porphyrins are typically isolated as crystalline solids exhibiting a deep purple to red-violet color, resulting from their extensive conjugated π-electron system that enables strong absorption in the visible spectrum.[18] This coloration is a hallmark of the porphyrin macrocycle, with variations in hue influenced by substituents but consistently tied to the core aromatic structure. Regarding solubility, free-base porphyrins are generally insoluble in water due to their hydrophobic nature but readily dissolve in organic solvents such as chloroform, dichloromethane, and pyridine.[19] Substituent modifications, such as the addition of sulfonate or carboxylate groups (e.g., in sulfonated tetraphenylporphyrin), significantly improve aqueous solubility by introducing hydrophilic functionalities, enabling applications in polar media.[20] The ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectrum of porphyrins features a characteristic intense Soret band (B-band) near 400 nm, attributed to a higher-energy π-π* transition, alongside weaker Q-bands in the 500–700 nm range corresponding to lower-energy π-π* excitations.[18] These spectral features are explained by the Gouterman four-orbital model, which posits that the porphyrin UV-Vis spectrum arises from transitions involving two nearly degenerate highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO-like a1u and b2u) and two lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMO-like eg set), with the Soret band's intensity stemming from allowed transitions and the Q-bands from partially forbidden ones due to nodal plane symmetries.[21] Free-base porphyrins display prominent fluorescence and phosphorescence, with fluorescence quantum yields often around 0.10, emitting in the red region (600–700 nm) following excitation of the Soret or Q-bands; these properties arise from the rigid, conjugated structure minimizing non-radiative decay.[22] In contrast, metal coordination typically quenches fluorescence by providing alternative decay pathways, such as metal-to-ligand charge transfer, though brief mention of such changes is noted here while detailed complex properties are addressed elsewhere. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides diagnostic signatures for porphyrins, with ¹H NMR showing meso protons deshielded at approximately 10 ppm due to the macrocycle's diatropic ring current, pyrrole β-protons at 8–9 ppm, and inner NH protons strongly shielded at -2 to -3 ppm.[23] Infrared (IR) spectra reveal characteristic bands for N-H stretching vibrations around 3300 cm⁻¹ in free-base forms and C=C stretching of the conjugated system near 1600 cm⁻¹, confirming the presence of the pyrrole units and extended double bonds.[24] Porphyrins exhibit good thermal stability as crystalline solids, with decomposition typically onsetting above 300–400°C under inert conditions, influenced by substituents that can either enhance or reduce this threshold through steric or electronic effects.Coordination Chemistry

Metal Complex Formation

Porphyrins form metal complexes through coordination at the central cavity defined by their four pyrrole nitrogen atoms, which create a square-planar binding site with a radius of approximately 2.0 Å, optimally suited for divalent transition metals and certain main group elements.[25] This N₄ donor set provides a stable dianionic ligand environment after deprotonation of the inner N-H bonds, enabling the metal ion to occupy the core and adopt specific geometries based on its electronic configuration and size. The cavity's rigidity and conjugation facilitate strong σ- and π-bonding interactions, making porphyrins versatile ligands for a wide range of metals.[26] The binding process begins with the approach of the metal ion to the porphyrin, often involving initial outer-sphere association followed by deformation of the macrocycle to accommodate insertion. Deprotonation of the two N-H bonds is crucial, releasing strain energy (up to 191 kJ/mol in some cases) as the metal coordinates to all four nitrogens and moves into the plane; this step is typically base-assisted and can be rate-limiting for certain metals. For many complexes, axial ligation occurs subsequently or concurrently, with ligands binding perpendicular to the porphyrin plane. Equilibrium constants for metal insertion reflect the stability of these complexes, with log K values for Cu²⁺ ranging from approximately 10 to 15 depending on the porphyrin substituents and solvent conditions.[27][28] Common metals incorporated into porphyrins span first-row transition elements such as Fe, Co, and Ni, which form stable complexes due to favorable size matching and electronic compatibility with the N₄ cavity. Second-row transition metals like Ru and Pd also readily coordinate, often exhibiting enhanced stability from stronger metal-ligand bonds. Recent advances have extended this to main group elements, particularly Group 15, with phosphorus(V) complexes synthesized and characterized between 2023 and 2025, including a phosphorus(V)-centered porphyrin with redox- and air-stable axial P–H bonds, highlighting expanded reactivity and potential applications in catalysis and materials.[29][30][31] In biological systems, this chemistry is exemplified by heme, where Fe²⁺ or Fe³⁺ coordinates within protoporphyrin IX.[32] The resulting coordination geometry varies with the metal: d⁸ ions like Ni²⁺ and Pd²⁺ typically adopt a square-planar arrangement (CN=4), remaining low-spin and diamagnetic without axial ligands. For metals like Fe²⁺/³⁺ or Co²⁺, the geometry is often octahedral (CN=6) due to axial ligation by substrates or solvents, which modulates electronic properties. Saddle-shaped distortions of the porphyrin core can arise in complexes with larger metals or bulky substituents, leading to out-of-plane pyrrole tilting and altered bonding, as seen in certain Fe(III) or Ni(II) derivatives.[26][32] Synthetic methods for metallation emphasize direct insertion, where free-base porphyrins react with metal salts (e.g., acetates or chlorides) under reflux in polar aprotic solvents like DMF, often with added base to facilitate deprotonation and achieve high yields (up to 90% for Cu and Ni). Template synthesis represents an alternative, particularly for challenging metals, where the ion templates the cyclization of porphyrin precursors during macrocycle assembly, enhancing selectivity and incorporating the metal in situ.[33][34] These approaches allow precise control over complex formation while avoiding harsh conditions.Properties of Complexes

Metalloporphyrin complexes exhibit distinct electronic properties compared to free-base porphyrins, primarily due to metal-ligand interactions that introduce charge transfer transitions. In particular, metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) bands appear in the UV-Vis spectra of certain metalloporphyrins, such as those with iron or ruthenium centers, where electron density shifts from the metal d-orbitals to the porphyrin π* orbitals, often observed in the visible region around 400-500 nm. These MLCT transitions contribute to the intense coloration and photochemical reactivity of the complexes. Additionally, the incorporation of metals shifts the redox potentials of the porphyrin ring and metal center; for example, the Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ couple in heme proteins like myoglobin has a midpoint potential of approximately +0.028 V vs. NHE, modulated by axial ligands and the protein environment to facilitate electron transfer in biological systems. The reactivity of metalloporphyrins is notably enhanced by their ability to bind axial ligands, with binding affinities varying based on the ligand's nucleophilicity and the metal's coordination preferences. Imidazole ligands bind more strongly to iron(III) porphyrins than water, with formation constants for bis(imidazole) complexes around 10⁵-10⁶ M⁻² in aqueous media, reflecting the preference for nitrogen donors in mimicking heme active sites.[35] This axial coordination influences reactivity, as seen in cobalt(II) porphyrins, which reversibly bind O₂ with affinities comparable to cobalt-substituted myoglobin (equilibrium constant K_O2 ≈ 10³-10⁴ torr⁻¹ at low temperatures), enabling model studies of oxygen transport without irreversible oxidation.[36] Stability of metalloporphyrin complexes is governed by high thermodynamic formation constants, reflecting the strong chelation of the tetradentate porphyrin ligand to the metal ion. For iron(II) tetraphenylporphyrin, the overall stability constant (β₄) exceeds 10³⁰, indicating exceptional robustness under physiological conditions, though sensitivity to oxidation can lead to ring degradation upon exposure to strong oxidants.[37] These complexes are generally stable to reduction but may undergo metal extrusion under extreme pH or reductive conditions. Spectroscopic properties of metalloporphyrins differ markedly from free-base forms due to metal-induced perturbations. The Soret band, a characteristic π-π* transition, shifts to longer wavelengths in zinc(II) porphyrins, typically appearing at ~423-430 nm, compared to ~418 nm in the free base, arising from the filled d¹⁰ configuration that stabilizes the excited state.[38] For paramagnetic metals like Cu²⁺, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy reveals g-values around 2.0-2.2 and hyperfine splitting from nitrogen nuclei, providing insights into the square-planar geometry and unpaired electron delocalization over the porphyrin ring.[39] Recent advances highlight unique properties in main group metal complexes of modified porphyrins, such as phosphaporphyrins, where phosphorus substitution introduces σ-π interactions that alter electronic delocalization and enhance stability for optoelectronic applications. These systems exhibit tunable redox potentials and luminescence, with coordination to metals like aluminum or gallium yielding complexes stable under ambient conditions and showing potential in sensing due to their distinct charge transfer characteristics.[30]Synthesis Methods

Biological Biosynthesis

The biological biosynthesis of porphyrins primarily occurs through the heme biosynthetic pathway, a conserved enzymatic process in most organisms that produces protoporphyrin IX as a key intermediate, which is then modified into heme or other derivatives. This pathway begins in the mitochondria and involves shuttling intermediates to the cytosol, comprising eight enzymatic steps that convert simple precursors into the macrocyclic structure. The process is essential for generating heme, a cofactor in proteins like hemoglobin and cytochromes, and shares early steps with the synthesis of chlorophyll in photosynthetic organisms.[3] The pathway initiates with the condensation of glycine and succinyl-CoA to form δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), the first committed precursor, catalyzed by ALA synthase (ALAS), which is the rate-limiting enzyme. This reaction occurs in the mitochondria and releases CO₂ and CoA as byproducts: Two molecules of ALA are then dehydrated in the cytosol by ALA dehydratase to form porphobilinogen (PBG), a pyrrole unit that serves as the building block for the porphyrin ring. Four PBG molecules are polymerized by hydroxymethylbilane synthase (also known as porphobilinogen deaminase) to produce the linear tetrapyrrole hydroxymethylbilane. Uroporphyrinogen III synthase then rearranges and cyclizes this intermediate to yield uroporphyrinogen III, introducing the critical asymmetric chirality at the D-ring that distinguishes the natural isomer from its symmetric counterpart.[3][40] Subsequent decarboxylation of uroporphyrinogen III by uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase produces coproporphyrinogen III, which is transported back to the mitochondria. There, coproporphyrinogen oxidase decarboxylates and oxidizes two propionate side chains to vinyl groups, forming protoporphyrinogen IX. Protoporphyrinogen oxidase further oxidizes this to protoporphyrin IX, the fully conjugated porphyrin. Finally, ferrochelatase inserts ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) into protoporphyrin IX to complete heme b formation. In mammals, two ALAS isoforms exist: ALAS1 in the liver, responsive to nutritional and drug induction, and ALAS2 in erythroid cells, regulated by iron-responsive elements for hemoglobin production.[3][41] The pathway is tightly regulated, primarily through feedback inhibition by heme, which represses ALAS transcription, mRNA stability, and mitochondrial import, preventing overaccumulation of intermediates. Heme also allosterically inhibits ALAS activity and influences downstream enzymes like ferrochelatase. Defects in these enzymes lead to porphyrias, a group of disorders characterized by accumulation of toxic porphyrin precursors; for example, deficiencies in hydroxymethylbilane synthase cause acute intermittent porphyria with ALA and PBG buildup, while ferrochelatase mutations result in erythropoietic protoporphyria with protoporphyrin IX accumulation and photosensitivity.[40][41][42] In plants and bacteria, the pathway diverges at protoporphyrin IX, where magnesium chelatase inserts Mg²⁺ instead of Fe²⁺, directing the intermediate toward chlorophyll biosynthesis via subsequent methylation and cyclization steps to form the isocyclic ring. This branch supports photosynthesis by producing chlorophyll a and b, with the Mg insertion step serving as the key divergence point from heme production.[43][44]Laboratory Synthesis

Laboratory synthesis of porphyrins primarily relies on acid-catalyzed condensations of pyrrole derivatives with aldehydes, followed by oxidation to form the macrocyclic structure. These abiotic methods allow for the preparation of symmetric and asymmetric variants, distinct from enzymatic pathways, and have been refined over decades to improve yield and substituent control. Early approaches focused on one-pot reactions, while contemporary strategies emphasize stepwise assembly and sustainable conditions. The foundational Rothemund synthesis, introduced in 1935, involves heating pyrrole with an aldehyde such as benzaldehyde in propionic acid under reflux, leading to the formation of tetraphenylporphyrin (TPP) through condensation and aerial oxidation.[45] This method, though simple, typically affords low yields (around 1-10%) due to side reactions forming oligomeric byproducts and requires harsh conditions like prolonged heating at 140-180°C.[46] An improvement came with the Adler-Longo method in 1964, which employs dilute solutions (approximately 0.05 M) of pyrrole and aldehyde in propionic acid to suppress polymerization, achieving reproducible yields of 20-30% for meso-tetraphenylporphyrin after chromatographic purification.[14] This variant maintains the one-pot nature but enhances selectivity by controlling reactant concentrations and reaction time, making it a standard for preparing symmetric meso-arylporphyrins.[47] For greater regiochemical control, particularly in unsymmetric porphyrins, the dipyrromethane route developed by Lindsey provides a modular alternative. This stepwise process first forms a dipyrromethane by acid-catalyzed condensation of pyrrole with one aldehyde, followed by reaction of two dipyrromethane units with a second aldehyde to yield a porphyrinogen intermediate, which is then oxidized (often with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone or air) to the porphyrin.[48] Yields can exceed 30% for trans-A2B2 isomers with careful control of acid catalysis (e.g., using BF3·OEt2 or TFA), enabling precise placement of up to four different meso-substituents. Recent advancements prioritize sustainability, including microwave-assisted protocols that accelerate the Adler-Longo-type condensation, reducing reaction times from hours to minutes while minimizing solvent volume and achieving comparable yields for TPP (up to 25%).[49] Greener oxidations have also emerged, aiming to replace stoichiometric oxidants like DDQ with more sustainable alternatives.[46] These approaches lower environmental impact and scale better for industrial applications. Despite progress, laboratory synthesis faces challenges in regioselectivity for asymmetric structures, where statistical mixtures complicate isolation and yields often fall below 10% without optimized conditions.[48] Purification typically involves column chromatography on silica or alumina, exploiting solubility differences, though recycling solvents and catalysts is increasingly incorporated in modern protocols. Template-directed strategies using metal ions, such as Cu(II) or Zn(II), have been employed to guide cyclization in dipyrromethane assemblies, enhancing efficiency by stabilizing intermediates through coordination.Natural Occurrence

Role in Biological Systems

Porphyrins serve as essential cofactors in numerous biological processes, particularly through their incorporation into metalloproteins that facilitate oxygen handling, electron transport, and light energy capture. In vertebrate animals, heme—a ferrous iron complex of protoporphyrin IX—forms the prosthetic group of hemoglobin and myoglobin, enabling reversible oxygen binding for transport and storage. Hemoglobin, a tetrameric protein in erythrocytes, coordinates oxygen at four heme sites in the lungs for delivery to tissues, while myoglobin, a monomeric protein in muscle cells, stores oxygen to support metabolic demands during activity. The planar structure of heme b, featuring protoporphyrin IX with four methyl, two vinyl, and two propionic acid substituents around the iron center, allows the Fe²⁺ ion to switch between high- and low-spin states upon oxygenation, optimizing affinity and release.[3][50][51] In mitochondrial respiration across eukaryotes and many prokaryotes, heme-containing cytochromes function as key electron carriers in the electron transport chain. Cytochromes b, c, and a, each with distinct heme variants, sequentially transfer electrons from NADH or FADH₂ to molecular oxygen, generating a proton gradient for ATP synthesis. Cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV), which binds heme a and copper ions, catalyzes the four-electron reduction of O₂ to H₂O, preventing harmful reactive oxygen species accumulation while coupling to proton pumping. This heme-mediated process sustains aerobic energy production, with cytochrome c shuttling electrons between complexes III and IV.[52][53] In oxygenic photosynthesis of plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, chlorophylls—magnesium complexes of chlorin rings derived from porphyrins—act as primary light-harvesting pigments in photosystems I and II. Chlorophyll a, with its conjugated tetrapyrrole macrocycle, absorbs red and blue wavelengths to excite electrons, initiating charge separation in reaction centers. Within light-harvesting complexes like LHCII, chlorophyll molecules aggregate in protein scaffolds to form antenna arrays that funnel excitons efficiently to the photosystems, enhancing quantum yield under varying light conditions. In anoxygenic photosynthesis of green sulfur bacteria, bacteriochlorophylls c, d, or e—further reduced porphyrin derivatives—self-assemble into chlorosomes, massive paracrystalline structures that enable light capture in low-intensity environments without protein scaffolds.[54][55][56] Beyond respiration and photosynthesis, heme porphyrins underpin antioxidant defense in catalases and peroxidases, which decompose hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen, mitigating oxidative stress. Catalase, a tetrameric heme enzyme, rapidly converts two H₂O₂ molecules in a ping-pong mechanism involving ferryl-oxo intermediates at the heme iron, protecting cells from lipid peroxidation. Peroxidases similarly use heme to reduce H₂O₂ while oxidizing substrates like halides. Relatedly, vitamin B₁₂ (cobalamin), featuring a corrin ring—a contracted, reduced analog of the porphyrin macrocycle—serves as a cobalt cofactor in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase and methionine synthase, facilitating carbon skeleton rearrangements and one-carbon transfers essential for metabolism.[57][58][59] Porphyrins represent ancient molecular innovations, with heme-based electron transport chains tracing back to the Archean Eon around 3.5 billion years ago, predating the Great Oxidation Event and enabling early microbial energy metabolism in anaerobic or microaerobic niches. Recent structural studies, including cryo-electron microscopy of chlorosomes in green sulfur bacteria, have illuminated how bacteriochlorophyll aggregates form multilayered, helical nanostructures that optimize exciton delocalization and energy transfer to reaction centers, informing models of efficient, self-organized light harvesting in primordial phototrophs.[60][61][62]Ancient and Fossil Porphyrins

The discovery of porphyrins in petroleum, marking the beginning of their study as geological biomarkers, is attributed to Alfred Treibs, who isolated them from oil-bearing rocks in 1934, demonstrating their derivation from biological precursors like chlorophyll.[2] These petroporphyrins, as they are termed in sedimentary contexts, occur widely in oil shales such as those from the Julia Creek deposit in Australia and the Tarfaya basin in Morocco, where they are extracted and analyzed to reveal their complex mixtures.[63] Through diagenetic processes, petroporphyrins form as degradation products of chlorophyll and heme, involving demetallation, alkylation, decarboxylation, and aromatization, which alter the original tetrapyrrole structures while preserving the core macrocycle.[64] Petroporphyrins serve as robust biomarkers due to the exceptional stability of their metal complexes, particularly vanadyl (VO) and nickel (Ni) forms, which resist degradation over geological timescales spanning millions to billions of years.[65] The ratio of vanadyl to nickel petroporphyrins provides insights into depositional environments, with vanadyl complexes predominating in anoxic marine settings and nickel complexes more common in terrestrial or less reducing conditions.[66] These compounds have been identified in sediments ranging from recent deposits to Precambrian rocks, including 1.1-billion-year-old marine shales that indicate early photosynthetic ecosystems dominated by bacteria.[67] Such findings aid in reconstructing paleoenvironments, including oxygenation levels and organic matter sources in ancient basins.[68] Analytical techniques for petroporphyrins rely heavily on mass spectrometry to characterize these molecular fossils, with methods like electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (ESI-FT-ICR MS) enabling detailed compositional analysis of their homologues.[69] Recent advances in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), particularly from 2023 studies on shale samples, have improved trace-level detection by enhancing separation of metalloporphyrin isomers and reducing matrix interferences in complex geological extracts.[70] These developments allow for higher sensitivity in identifying low-abundance petroporphyrins, facilitating precise biomarker correlations.[71] The presence of petroporphyrins in ancient sediments provides direct chemical evidence for the early evolution of photosynthesis, as their origins trace back to chlorophyll-based pigments in primordial microbial communities, distinct from but analogous to modern biological porphyrins.[67]Applications

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) utilizes porphyrin-based photosensitizers to treat various cancers through light activation, offering a minimally invasive alternative to traditional therapies. In this approach, the photosensitizer is administered systemically and selectively accumulates in tumor tissues, where it is excited by specific wavelengths of light to produce cytotoxic reactive oxygen species, primarily singlet oxygen, leading to localized cell death via mechanisms such as apoptosis, necrosis, and vascular damage.[72] The mechanism of porphyrin-mediated PDT involves the photosensitizer absorbing light, typically at around 630 nm for first-generation agents, transitioning to an excited triplet state that transfers energy to molecular oxygen, generating singlet oxygen with a short diffusion radius of approximately 20 nm. This reactive species induces oxidative damage to cellular components, including membranes, proteins, and DNA, ultimately causing tumor cell destruction. A key example is Photofrin, a mixture of hematoporphyrin derivatives including porfimer sodium, which serves as the prototypical porphyrin photosensitizer in clinical PDT.[72][73] Selective tumor accumulation occurs primarily through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, where leaky tumor vasculature allows preferential uptake and retention of the photosensitizer compared to normal tissues. Porfimer sodium exhibits a long terminal plasma elimination half-life of approximately 17-21 days, necessitating precautions against prolonged photosensitivity.[74] Porfimer sodium (Photofrin) was approved by the FDA in December 1995 for the palliation of obstructing esophageal cancer and later for other indications, marking the first porphyrin-based agent for PDT in oncology. Another notable porphyrin derivative is benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A (BPD-MA, verteporfin), which has demonstrated efficacy in preclinical and early clinical studies for cancers such as melanoma and prostate cancer, absorbing at longer wavelengths (around 690 nm) for deeper tissue penetration. Clinical efficacy of porphyrin PDT is particularly pronounced in early-stage cancers, with complete response rates often ranging from 70% to 90% in superficial or localized lesions, such as early esophageal or lung tumors, due to precise light delivery. However, common side effects include cutaneous photosensitivity lasting weeks and transient local inflammation at the treatment site.[75][76] Recent advances in porphyrin PDT focus on improving targeting and efficacy through nanoparticle formulations and conjugates. For instance, cell membrane-coated porphyrin-based nanoscale metal-organic frameworks (por-nMOFs) enhance tumor-specific delivery by mimicking cellular surfaces for immune evasion and improved EPR-mediated accumulation, as reviewed in 2024 studies showing augmented singlet oxygen generation and reduced off-target effects. These innovations, including targeted porphyrin-nanoparticle hybrids, aim to overcome limitations like poor solubility and hypoxia in solid tumors, expanding PDT's applicability to more advanced cancers.[77]Catalysis and Energy Conversion

Porphyrins and their metal complexes serve as efficient electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) in fuel cells, particularly cobalt porphyrins, which facilitate the four-electron reduction pathway with minimal overpotentials. For instance, asymmetrically coordinated cobalt single-atom catalysts exhibit an ORR overpotential of 0.39 V, enabling operation close to the thermodynamic potential while maintaining high selectivity for water formation over peroxide.[78] These catalysts leverage the Co-N4 coordination site to stabilize key intermediates like *OOH and *OH, reducing energy barriers for proton-coupled electron transfers.[79] In photocatalysis, porphyrin sensitizers play a crucial role in driving hydrogen evolution by absorbing visible light and transferring excited electrons to sacrificial donors or catalysts. Zinc porphyrin-based systems, when coupled with platinum nanoparticles, achieve quantum yields up to 17% at 710 nm for H2 production, highlighting their efficacy in near-infrared light utilization.[80] For CO2 reduction, porphyrin-incorporated metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) enhance selectivity and efficiency; a 2025 review details frameworks yielding products like CO and CH4, attributed to improved charge separation and CO2 adsorption within the porous structure.[81] These materials mimic natural photosynthetic antennas by extending light-harvesting ranges into the red region.[82] Artificial photosynthesis employs porphyrin-based dyads featuring donor-acceptor architectures to achieve long-lived charge separation, emulating chlorophyll's role in natural systems. In ferrocene-zinc porphyrin-fullerene dyads, photoexcitation generates charge-separated states with lifetimes exceeding 380 ms, enabling efficient vectorial electron transfer across the molecular scaffold.[83] Such configurations prevent rapid recombination, sustaining redox gradients for multi-electron processes like water oxidation and reduction. Recent nanoparticle-enhanced variants extend this lifetime to 4.3 ms in aqueous media, promoting scalability for solar fuel production.[84] Main group metalloporphyrins, such as those with tin (Sn) and germanium (Ge), catalyze water splitting via hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) pathways. These catalysts offer stability in neutral media, contrasting transition metal variants prone to degradation.[85][86] Iron porphyrins exemplify robust catalysis in C-H bond activation, enabling selective functionalization under mild conditions with high stability. Biomimetic Fe-porphyrin complexes, inspired by cytochrome P450, mediate C-H hydroxylation.[87] This efficiency stems from the iron-oxo intermediate's ability to abstract hydrogen atoms with low barriers, followed by oxygen rebound, while axial ligands modulate selectivity to avoid over-oxidation.[88]Sensors and Molecular Electronics

Porphyrins and their metal complexes have been extensively utilized in ion-selective sensors due to their ability to form coordination complexes with heavy metal ions, often leading to detectable changes in optical or electrochemical properties. Metalloporphyrins exhibit changes in optical properties upon binding heavy metal ions like Pb²⁺, providing high selectivity. Comprehensive reviews highlight that such sensors operate via reversible binding, with response times under 1 minute, making them suitable for environmental monitoring.[89] In gas sensing applications, synthetic porphyrin complexes mimic the axial ligand binding sites of heme proteins, facilitating the detection of nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO) through changes in electronic spectra or conductivity. These heme mimics leverage the porphyrin's π-system for enhanced sensitivity, distinguishing NO from CO based on steric hindrance at the binding site. Such systems have been integrated into optical fiber sensors for real-time monitoring in biomedical and industrial settings.[90][91] Porphyrins serve as key building blocks in molecular electronics, particularly in self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) that function as molecular wires for charge transport. Zinc porphyrin-based SAMs on gold electrodes demonstrate efficient conductance over lengths up to 14 nm, with current densities around 10 nA at 0.5 V bias, attributed to through-bond π-conjugation. Extended porphyrin tapes, featuring fused units with conjugation lengths greater than 10 porphyrin rings, exhibit bias-dependent conductance increases of over 10-fold at 0.7 V, defying typical length-dependent decay and enabling ballistic-like transport. These structures have been pivotal in single-molecule junctions, showcasing rectification ratios up to 10:1.[92][93] In solar cell applications, porphyrin-fullerene dyads form donor-acceptor architectures that enhance charge separation and photovoltaic efficiency in organic and dye-sensitized systems. These dyads, where the porphyrin acts as an electron donor linked covalently to C₆₀ fullerene, achieve photoinduced electron transfer yields near 100% within picoseconds, contributing to power conversion efficiencies of approximately 12% in third-generation photovoltaics. Seminal studies in Coordination Chemistry Reviews emphasize their role in bulk heterojunctions, where optimized linker lengths minimize recombination losses. Recent donor-acceptor dyads have pushed efficiencies to 13% in porphyrin-sensitized cells by improving light harvesting in the 400-700 nm range.[94][95] Recent advances incorporate porphyrin-based metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) into chemiresistive sensors, exploiting their porous structures for selective gas adsorption and conductivity modulation. For example, PCN-222 MOFs with varying central metals (e.g., Zr, Fe) show NO₂ detection limits of 0.5 ppm at room temperature, with response times under 30 seconds, due to charge transfer upon analyte binding within the porphyrin pores. These 2023-2024 developments highlight tunable selectivity by metal substitution, achieving up to 5-fold resistance changes for environmental pollutants like SO₂. Such MOFs integrate seamlessly with flexible electronics, offering stability over 100 cycles.[96][97]Biomedical and Toxicological Uses

Porphyrin conjugates serve as versatile platforms for drug delivery in biomedical applications beyond photodynamic mechanisms. Gadolinium(III)-porphyrin complexes, such as those conjugated to chitosan nanoparticles, function as MRI contrast agents by enhancing relaxivity and enabling targeted imaging of tissues, with in vitro studies demonstrating improved signal intensity compared to free Gd agents.[98] Similarly, porphyrin-linked nanostructures, including gold nanorods conjugated with porphyrins and targeting ligands like trastuzumab, facilitate photothermal therapy by accumulating in tumor sites and converting near-infrared light to localized heat, achieving significant cell ablation in HER2-positive breast cancer models without systemic toxicity.[99] Porphyrins also exhibit inherent antimicrobial properties, primarily through cationic interactions that disrupt bacterial cell membranes. Amphiphilic porphyrin-binding peptides, for instance, preferentially bind to anionic lipid bilayers in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, leading to membrane permeabilization and broad-spectrum activity with minimum inhibitory concentrations as low as 0.47 μM against pathogens like Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.[100] Recent innovations incorporate porphyrins into cell membrane-coated nanoparticles, which mimic host cells to evade immune detection and enable targeted delivery to infection sites, enhancing antibacterial efficacy against resistant strains in preclinical models of bacterial infections.[101] Toxicological profiles of porphyrins and their precursors reveal risks associated with metabolic overload. Acute exposure to excess 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), a key porphyrin biosynthesis intermediate, induces photosensitivity reactions and neurological symptoms including severe abdominal pain, peripheral neuropathy, seizures, and psychiatric disturbances, as seen in conditions like acute intermittent porphyria and hereditary tyrosinemia type 1.[102] Chronic lead exposure exacerbates these effects by inhibiting ALA dehydratase, causing porphyrin precursor accumulation that mimics porphyria with symptoms such as recurrent abdominal pain, anemia, and basophilic stippling in erythrocytes, often misdiagnosed without blood lead level confirmation.[103] Porphyrias encompass a group of inherited metabolic disorders arising from partial deficiencies in heme biosynthetic enzymes, resulting in toxic porphyrin buildup primarily in the liver or skin. Acute hepatic forms, such as acute intermittent porphyria, present with life-threatening neurovisceral attacks featuring excruciating abdominal pain, vomiting, hypertension, tachycardia, and progressive neuropathy or encephalopathy, while variegate porphyria additionally causes photosensitive skin blistering.[104] Management focuses on symptomatic relief and precursor reduction; intravenous hemin infusion at 3–4 mg/kg daily for 4–14 days represses hepatic ALA synthase, alleviating attacks in over 80% of cases, though supportive measures like carbohydrate loading and pain control are essential.[104] Liver transplantation serves as a curative option for recurrent, refractory cases.[104] Safety assessments indicate porphyrins generally possess low acute toxicity. Environmentally, porphyrins demonstrate limited persistence in aqueous systems, degrading under natural conditions and posing low ecotoxicological hazards, which supports their application in water remediation without long-term bioaccumulation.[105]Related Compounds

Natural Porphyrin Derivatives

Natural porphyrin derivatives encompass a diverse array of compounds derived from the porphyrin macrocycle, occurring in various biological contexts across plants, animals, and microorganisms. These derivatives include both cyclic and open-chain structures that serve as intermediates or pigments, with modifications such as metal coordination or ring reductions distinguishing them from the parent porphyrin. Key examples include heme precursors and photosynthetic pigments, which are biosynthesized through enzymatic modifications of protoporphyrin IX or related tetrapyrroles.[2] Protoporphyrin IX is a prominent natural porphyrin derivative characterized by a fully unsaturated macrocycle with four methyl, two vinyl, and two propionic acid side chains, acting as the immediate precursor to heme in the biosynthetic pathway. It occurs in avian eggshells, where it contributes to pigmentation, particularly in brown-shelled eggs produced by shell gland epithelial cells. Additionally, protoporphyrin IX has been identified in marine organisms, including pigments in certain coral-associated structures and snail shells, highlighting its role in biomineralization processes.[2][106][107] Uroporphyrin and coproporphyrin represent early intermediates in heme biosynthesis, featuring eight and four carboxylic acid side chains, respectively, on the porphyrin ring. These hydrophilic compounds are naturally excreted in human urine as byproducts of incomplete heme synthesis, with coproporphyrin being the predominant urinary porphyrin under normal conditions and uroporphyrin appearing in smaller amounts. Elevated levels of uroporphyrin and coproporphyrin in urine serve as key biomarkers for porphyrias, a group of metabolic disorders involving defects in heme production enzymes.[108][109][110] Chlorophylls a and b are magnesium-coordinated porphyrin derivatives essential to oxygenic photosynthesis, featuring a chlorin macrocycle (a partially reduced porphyrin) with a phytyl ester chain at the C-17 position for membrane anchoring. Chlorophyll a includes a vinyl group at C-3 and a cyclopentanone ring fused to the D ring, while chlorophyll b has a formyl group at C-7, shifting its absorption spectrum; both share the central Mg²⁺ ion and the hydrophobic phytyl tail derived from phytol alcohol. These structures enable efficient light harvesting in plant chloroplasts and algal thylakoids.[111][112] Bacteriochlorophylls, found in anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria such as purple sulfur and green sulfur species, possess a bacteriochlorin macrocycle resulting from further reduction of two opposite pyrrole rings compared to chlorophylls, which extends their absorption into the near-infrared region. This reduced structure, often with Mg²⁺ coordination and variations in ester chains (e.g., farnesyl or geranylgeranyl), allows these pigments to capture low-intensity light in anaerobic environments, supporting photosynthesis in deep-water or sediment habitats. Common variants include bacteriochlorophyll a and b, differing in side-chain substituents.[113][114] Phycobilins are linear, open-chain tetrapyrroles derived biosynthetically from porphyrin precursors via heme cleavage by heme oxygenase, lacking the closed macrocycle but retaining the conjugated pyrrole units. These pigments, including phycocyanobilin and phycoerythrobilin, occur in cyanobacteria and red algae, where they are covalently attached to phycobiliproteins in phycobilisomes for light harvesting in aquatic environments. Their open-chain configuration provides flexibility for protein binding and absorption in the visible spectrum.[115][116] Isolation of natural porphyrin derivatives from biological tissues typically involves solvent extraction to separate the lipophilic macrocycles from proteins and lipids. A standard method homogenizes fresh or frozen tissues in 80% acetone to solubilize pigments, followed by acidification with 2-5% HCl in acetone to protonate and extract free porphyrins into the organic phase while precipitating proteins. The extract is then centrifuged, and the supernatant is neutralized or further purified via chromatography for analysis, ensuring recovery of compounds like protoporphyrin and chlorophylls without degradation.[117][118]Synthetic Porphyrins

Synthetic porphyrins encompass a diverse class of engineered macrocycles designed to mimic or extend the functionalities of natural porphyrins, often incorporating peripheral modifications to enhance solubility, stability, or specific interactions. Water-soluble analogs, such as meso-tetrasulfonatophenylporphyrin (TPPS4), feature sulfonate groups on the meso-phenyl substituents, enabling their use in aqueous environments for biomimetic studies of porphyrin-metal ion interactions and protein binding.[119] These compounds facilitate investigations into heme-like coordination and aggregation behaviors that parallel biological systems, with TPPS4 demonstrating affinity for serum albumin transport mechanisms.[119] Cofacial dimers represent another key class of synthetic porphyrins, where two macrocycles are positioned face-to-face to replicate the spatial arrangement of enzyme active sites, such as those in diiron or dimanganese proteins involved in oxygen activation. These dimers are typically linked by covalent straps or rigid pillars, which control the interporphyrin distance and orientation, promoting cooperative reactivity like dioxygen binding or peroxide disproportionation.[120] For instance, manganese cofacial diporphyrins have been employed as functional models for the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II, exhibiting catalytic activity for water oxidation.[120] Such structures also enable studies of electronic coupling and exciton dynamics, as seen in bioinspired zinc or cobalt variants.[121] Porphyrin arrays extend these concepts into higher-order architectures, leveraging supramolecular interactions to form extended structures like linear tapes or cyclic wheels for applications in energy transfer and molecular electronics. Linear tapes arise from the coordination-driven self-assembly of pyridyl-substituted porphyrins with metal linkers, such as trans-PdCl2, yielding one-dimensional polymers with tunable lengths and enhanced photophysical properties like efficient energy migration.[122] Cyclic wheels, on the other hand, are constructed via templated assembly of multiple porphyrin units around a central core, often using zinc coordination to form stable, wheel-like nanoring complexes on the micrometer scale.[123] These arrays exhibit ordered packing that supports through-space electronic communication, making them ideal for supramolecular devices.[122] Recent advances in synthetic porphyrins include porphyrin-peptide hybrids that promote self-assembly into nanostructures for biomedical and photocatalytic applications, as demonstrated in 2024 studies where peptide conjugation directs hierarchical organization into nanofibers or cages with improved biocompatibility. Expanded porphyrins, such as sapphyrins—a pentapyrrolic 22π-electron system—offer larger cavities for anion binding and tumor localization, synthesized via acid-catalyzed condensation of pyrrole precursors with enhanced aromaticity upon metallation.[124] These derivatives exhibit unique photophysical properties, including near-infrared absorption, suitable for imaging and sensing.[124] Purification and characterization of synthetic porphyrins typically involve high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for separation based on hydrophobicity or charge, often using reversed-phase columns to isolate isomers or aggregates.[125] Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) confirms molecular weights and composition, providing high-resolution spectra for verifying conjugation or metallation without fragmentation.[126] These techniques ensure the structural integrity of tailored porphyrins for downstream research.[127]Modified and Isomeric Structures

Core-modified porphyrins involve the replacement of one or more nitrogen atoms in the standard porphyrin core with other heteroatoms or carbon, leading to unique electronic and coordination properties distinct from the classic 18π-electron aromatic system. N-confused porphyrins (NCPs), where one pyrrole nitrogen is replaced by a CH group inverted in the macrocycle, were first synthesized in 1994 and exhibit inverted coordination sites, enabling stable organometallic bonds at the peripheral carbon. These modifications often result in altered redox potentials and enhanced stability for unusual metal oxidation states, such as Cu(III) in doubly N-confused variants. Oxaporphyrins, featuring an oxygen atom in place of a nitrogen, display contracted macrocyclic structures with reduced aromaticity due to the electronegative oxygen disrupting the π-conjugation, leading to spectroscopic shifts like intensified Soret-like bands around 400-450 nm.[128][129] Isomeric porphyrin structures rearrange the connectivity of the four pyrrole units and meso carbons, yielding macrocycles with different topologies and aromatic characteristics compared to the standard porphyrin. Porphycene, the first synthetic isomer discovered in 1986, features two bipyrrole units connected by external meso carbons in a transoid arrangement, resulting in a more rectangular shape and intensified absorption/emission in the red region (around 600-700 nm) due to enhanced π-overlap. This isomer binds metals similarly to porphyrins but with higher affinity for certain divalent ions owing to its contracted cavity. Corroles, contracted isomers with three pyrroles and one direct C-C bond between the fourth pair, possess 18π electrons in their free-base form, conferring aromaticity, though protonation can lead to altered electronic properties, including potential antiaromatic contributions in dicationic states that disrupt planarity and conjugation. Corroles excel in stabilizing trivalent metals like Ga(III) and In(III), unlike porphyrins which prefer divalent ions, due to their anionic core.[130][16] Contracted porphyrinoids, such as subporphyrins, consist of three pyrrole units linked by meso carbons, forming a 14π-electron aromatic system that is more strained and bowl-shaped than porphyrins. First reported in 2006 for boron complexes, recent advances include free-base subporphyrins synthesized in 2022 via demetalation, exhibiting intense fluorescence and potential for chiral applications. Expanded porphyrinoids, with macrocycles exceeding 22 atoms (e.g., [131]hexaphyrins or larger), incorporate additional pyrrole or furan units, yielding Möbius aromaticity in twisted conformations or antiaromaticity in planar forms, with tunable near-IR absorption for optoelectronic uses. These structures often display Hückel aromaticity for (4n+2)π systems or Baird antiaromaticity for 4nπ electrons, influencing reactivity and metal coordination.[132] Synthesis of these modified and isomeric structures typically employs adaptations of classic methods, such as condensation of tripyrranes (linear tetrapyrrole precursors) with aldehydes followed by cyclization and oxidation, or modified Rothemund conditions using pyrrole and formaldehyde under acidic catalysis. For N-confused and oxaporphyrins, yields range from 5-15% due to regioselective confusion or heteroatom insertion challenges. Isomers like porphycene and corrole achieve 5-20% yields via bipyrrole dimerization or tripyrrane-formaldehyde reactions, respectively, with purification by chromatography essential to isolate the desired topology. These low-to-moderate yields reflect the thermodynamic preference for the standard porphyrin scaffold, but recent optimizations using microwave assistance or solvent-free conditions have improved scalability. Metal binding in these variants differs markedly; for instance, corroles form stable M(III) complexes without axial ligation, while subporphyrins prefer boron or aluminum chelation for planarity.[129][130][133]References

- Jul 29, 2020 · This radial expansion flattens the porphyrin core, inducing more planarity in the conformations of the six-coordinate Ni(II) porphyrin species.