Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

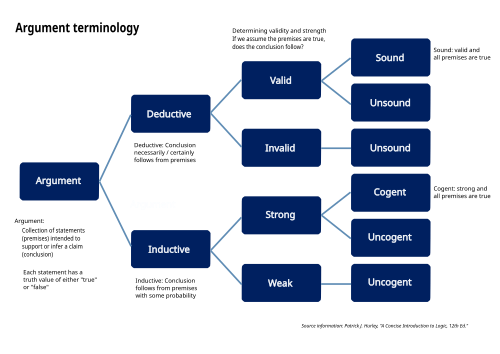

Deductive reasoning

View on WikipediaDeductive reasoning is the process of drawing valid inferences. An inference is valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, meaning that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false. For example, the inference from the premises "all men are mortal" and "Socrates is a man" to the conclusion "Socrates is mortal" is deductively valid. An argument is sound if it is valid and all its premises are true. One approach defines deduction in terms of the intentions of the author: they have to intend for the premises to offer deductive support to the conclusion. With the help of this modification, it is possible to distinguish valid from invalid deductive reasoning: it is invalid if the author's belief about the deductive support is false, but even invalid deductive reasoning is a form of deductive reasoning.

Deductive logic studies under what conditions an argument is valid. According to the semantic approach, an argument is valid if there is no possible interpretation of the argument whereby its premises are true and its conclusion is false. The syntactic approach, by contrast, focuses on rules of inference, that is, schemas of drawing a conclusion from a set of premises based only on their logical form. There are various rules of inference, such as modus ponens and modus tollens. Invalid deductive arguments, which do not follow a rule of inference, are called formal fallacies. Rules of inference are definitory rules and contrast with strategic rules, which specify what inferences one needs to draw in order to arrive at an intended conclusion.

Deductive reasoning contrasts with non-deductive or ampliative reasoning. For ampliative arguments, such as inductive or abductive arguments, the premises offer weaker support to their conclusion: they indicate that it is most likely, but they do not guarantee its truth. They make up for this drawback with their ability to provide genuinely new information (that is, information not already found in the premises), unlike deductive arguments.

Cognitive psychology investigates the mental processes responsible for deductive reasoning. One of its topics concerns the factors determining whether people draw valid or invalid deductive inferences. One such factor is the form of the argument: for example, people draw valid inferences more successfully for arguments of the form modus ponens than of the form modus tollens. Another factor is the content of the arguments: people are more likely to believe that an argument is valid if the claim made in its conclusion is plausible. A general finding is that people tend to perform better for realistic and concrete cases than for abstract cases. Psychological theories of deductive reasoning aim to explain these findings by providing an account of the underlying psychological processes. Mental logic theories hold that deductive reasoning is a language-like process that happens through the manipulation of representations using rules of inference. Mental model theories, on the other hand, claim that deductive reasoning involves models of possible states of the world without the medium of language or rules of inference. According to dual-process theories of reasoning, there are two qualitatively different cognitive systems responsible for reasoning.

The problem of deduction is relevant to various fields and issues. Epistemology tries to understand how justification is transferred from the belief in the premises to the belief in the conclusion in the process of deductive reasoning. Probability logic studies how the probability of the premises of an inference affects the probability of its conclusion. The controversial thesis of deductivism denies that there are other correct forms of inference besides deduction. Natural deduction is a type of proof system based on simple and self-evident rules of inference. In philosophy, the geometrical method is a way of philosophizing that starts from a small set of self-evident axioms and tries to build a comprehensive logical system using deductive reasoning.

Definition

[edit]Deductive reasoning is the psychological process of drawing deductive inferences. An inference is a set of premises together with a conclusion. This psychological process starts from the premises and reasons to a conclusion based on and supported by these premises. If the reasoning was done correctly, it results in a valid deduction: the truth of the premises ensures the truth of the conclusion.[1][2][3][4] For example, in the syllogistic argument "all frogs are amphibians; no cats are amphibians; therefore, no cats are frogs" the conclusion is true because its two premises are true. But even arguments with wrong premises can be deductively valid if they obey this principle, as in "all frogs are mammals; no cats are mammals; therefore, no cats are frogs". If the premises of a valid argument are true, then it is called a sound argument.[5]

The relation between the premises and the conclusion of a deductive argument is usually referred to as "logical consequence". According to Alfred Tarski, logical consequence has 3 essential features: it is necessary, formal, and knowable a priori.[6][7] It is necessary in the sense that the premises of valid deductive arguments necessitate the conclusion: it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false, independent of any other circumstances.[6][7] Logical consequence is formal in the sense that it depends only on the form or the syntax of the premises and the conclusion. This means that the validity of a particular argument does not depend on the specific contents of this argument. If it is valid, then any argument with the same logical form is also valid, no matter how different it is on the level of its contents.[6][7] Logical consequence is knowable a priori in the sense that no empirical knowledge of the world is necessary to determine whether a deduction is valid. So it is not necessary to engage in any form of empirical investigation.[6][7] Some logicians define deduction in terms of possible worlds: A deductive inference is valid if and only if, there is no possible world in which its conclusion is false while its premises are true. This means that there are no counterexamples: the conclusion is true in all such cases, not just in most cases.[1]

It has been argued against this and similar definitions that they fail to distinguish between valid and invalid deductive reasoning, i.e. they leave it open whether there are invalid deductive inferences and how to define them.[8][9] Some authors define deductive reasoning in psychological terms in order to avoid this problem. According to Mark Vorobey, whether an argument is deductive depends on the psychological state of the person making the argument: "An argument is deductive if, and only if, the author of the argument believes that the truth of the premises necessitates (guarantees) the truth of the conclusion".[8] A similar formulation holds that the speaker claims or intends that the premises offer deductive support for their conclusion.[10][11] This is sometimes categorized as a speaker-determined definition of deduction since it depends also on the speaker whether the argument in question is deductive or not. For speakerless definitions, on the other hand, only the argument itself matters independent of the speaker.[9] One advantage of this type of formulation is that it makes it possible to distinguish between good or valid and bad or invalid deductive arguments: the argument is good if the author's belief concerning the relation between the premises and the conclusion is true, otherwise it is bad.[8] One consequence of this approach is that deductive arguments cannot be identified by the law of inference they use. For example, an argument of the form modus ponens may be non-deductive if the author's beliefs are sufficiently confused. That brings with it an important drawback of this definition: it is difficult to apply to concrete cases since the intentions of the author are usually not explicitly stated.[8]

Deductive reasoning is studied in logic, psychology, and the cognitive sciences.[3][1] Some theorists emphasize in their definition the difference between these fields. On this view, psychology studies deductive reasoning as an empirical mental process, i.e. what happens when humans engage in reasoning.[3][1] But the descriptive question of how actual reasoning happens is different from the normative question of how it should happen or what constitutes correct deductive reasoning, which is studied by logic.[3][12][6] This is sometimes expressed by stating that, strictly speaking, logic does not study deductive reasoning but the deductive relation between premises and a conclusion known as logical consequence. But this distinction is not always precisely observed in the academic literature.[3] One important aspect of this difference is that logic is not interested in whether the conclusion of an argument is sensible.[1] So from the premise "the printer has ink" one may draw the unhelpful conclusion "the printer has ink and the printer has ink and the printer has ink", which has little relevance from a psychological point of view. Instead, actual reasoners usually try to remove redundant or irrelevant information and make the relevant information more explicit.[1] The psychological study of deductive reasoning is also concerned with how good people are at drawing deductive inferences and with the factors determining their performance.[3][5] Deductive inferences are found both in natural language and in formal logical systems, such as propositional logic.[1][13]

Conceptions of deduction

[edit]Deductive arguments differ from non-deductive arguments in that the truth of their premises ensures the truth of their conclusion.[14][15][6] There are two important conceptions of what this exactly means. They are referred to as the syntactic and the semantic approach.[13][6][5] According to the syntactic approach, whether an argument is deductively valid depends only on its form, syntax, or structure. Two arguments have the same form if they use the same logical vocabulary in the same arrangement, even if their contents differ.[13][6][5] For example, the arguments "if it rains then the street will be wet; it rains; therefore, the street will be wet" and "if the meat is not cooled then it will spoil; the meat is not cooled; therefore, it will spoil" have the same logical form: they follow the modus ponens. Their form can be expressed more abstractly as "if A then B; A; therefore B" in order to make the common syntax explicit.[5] There are various other valid logical forms or rules of inference, like modus tollens or the disjunction elimination. The syntactic approach then holds that an argument is deductively valid if and only if its conclusion can be deduced from its premises using a valid rule of inference.[13][6][5] One difficulty for the syntactic approach is that it is usually necessary to express the argument in a formal language in order to assess whether it is valid. This often brings with it the difficulty of translating the natural language argument into a formal language, a process that comes with various problems of its own.[13] Another difficulty is due to the fact that the syntactic approach depends on the distinction between formal and non-formal features. While there is a wide agreement concerning the paradigmatic cases, there are also various controversial cases where it is not clear how this distinction is to be drawn.[16][12]

The semantic approach suggests an alternative definition of deductive validity. It is based on the idea that the sentences constituting the premises and conclusions have to be interpreted in order to determine whether the argument is valid.[13][6][5] This means that one ascribes semantic values to the expressions used in the sentences, such as the reference to an object for singular terms or to a truth-value for atomic sentences. The semantic approach is also referred to as the model-theoretic approach since the branch of mathematics known as model theory is often used to interpret these sentences.[13][6] Usually, many different interpretations are possible, such as whether a singular term refers to one object or to another. According to the semantic approach, an argument is deductively valid if and only if there is no possible interpretation where its premises are true and its conclusion is false.[13][6][5] Some objections to the semantic approach are based on the claim that the semantics of a language cannot be expressed in the same language, i.e. that a richer metalanguage is necessary. This would imply that the semantic approach cannot provide a universal account of deduction for language as an all-encompassing medium.[13][12]

Rules of inference

[edit]Deductive reasoning usually happens by applying rules of inference. A rule of inference is a way or schema of drawing a conclusion from a set of premises.[17] This happens usually based only on the logical form of the premises. A rule of inference is valid if, when applied to true premises, the conclusion cannot be false. A particular argument is valid if it follows a valid rule of inference. Deductive arguments that do not follow a valid rule of inference are called formal fallacies: the truth of their premises does not ensure the truth of their conclusion.[18][14]

In some cases, whether a rule of inference is valid depends on the logical system one is using. The dominant logical system is classical logic and the rules of inference listed here are all valid in classical logic. But so-called deviant logics provide a different account of which inferences are valid. For example, the rule of inference known as double negation elimination, i.e. that if a proposition is not not true then it is also true, is accepted in classical logic but rejected in intuitionistic logic.[19][20]

Prominent rules of inference

[edit]Modus ponens

[edit]Modus ponens (also known as "affirming the antecedent" or "the law of detachment") is the primary deductive rule of inference. It applies to arguments that have as first premise a conditional statement () and as second premise the antecedent () of the conditional statement. It obtains the consequent () of the conditional statement as its conclusion. The argument form is listed below:

- (First premise is a conditional statement)

- (Second premise is the antecedent)

- (Conclusion deduced is the consequent)

In this form of deductive reasoning, the consequent () obtains as the conclusion from the premises of a conditional statement () and its antecedent (). However, the antecedent () cannot be similarly obtained as the conclusion from the premises of the conditional statement () and the consequent (). Such an argument commits the logical fallacy of affirming the consequent.

The following is an example of an argument using modus ponens:

- If it is raining, then there are clouds in the sky.

- It is raining.

- Thus, there are clouds in the sky.

Modus tollens

[edit]Modus tollens (also known as "the law of contrapositive") is a deductive rule of inference. It validates an argument that has as premises a conditional statement (formula) and the negation of the consequent () and as conclusion the negation of the antecedent (). In contrast to modus ponens, reasoning with modus tollens goes in the opposite direction to that of the conditional. The general expression for modus tollens is the following:

- . (First premise is a conditional statement)

- . (Second premise is the negation of the consequent)

- . (Conclusion deduced is the negation of the antecedent)

The following is an example of an argument using modus tollens:

- If it is raining, then there are clouds in the sky.

- There are no clouds in the sky.

- Thus, it is not raining.

Hypothetical syllogism

[edit]A hypothetical syllogism is an inference that takes two conditional statements and forms a conclusion by combining the hypothesis of one statement with the conclusion of another. Here is the general form:

- Therefore, .

In there being a subformula in common between the two premises that does not occur in the consequence, this resembles syllogisms in term logic, although it differs in that this subformula is a proposition whereas in Aristotelian logic, this common element is a term and not a proposition.

The following is an example of an argument using a hypothetical syllogism:

- If there had been a thunderstorm, it would have rained.

- If it had rained, things would have gotten wet.

- Thus, if there had been a thunderstorm, things would have gotten wet.[21]

Fallacies

[edit]Various formal fallacies have been described. They are invalid forms of deductive reasoning.[18][14] An additional aspect of them is that they appear to be valid on some occasions or on the first impression. They may thereby seduce people into accepting and committing them.[22] One type of formal fallacy is affirming the consequent, as in "if John is a bachelor, then he is male; John is male; therefore, John is a bachelor".[23] This is similar to the valid rule of inference named modus ponens, but the second premise and the conclusion are switched around, which is why it is invalid. A similar formal fallacy is denying the antecedent, as in "if Othello is a bachelor, then he is male; Othello is not a bachelor; therefore, Othello is not male".[24][25] This is similar to the valid rule of inference called modus tollens, the difference being that the second premise and the conclusion are switched around. Other formal fallacies include affirming a disjunct, denying a conjunct, and the fallacy of the undistributed middle. All of them have in common that the truth of their premises does not ensure the truth of their conclusion. But it may still happen by coincidence that both the premises and the conclusion of formal fallacies are true.[18][14]

Definitory and strategic rules

[edit]Rules of inferences are definitory rules: they determine whether an argument is deductively valid or not. But reasoners are usually not just interested in making any kind of valid argument. Instead, they often have a specific point or conclusion that they wish to prove or refute. So given a set of premises, they are faced with the problem of choosing the relevant rules of inference for their deduction to arrive at their intended conclusion.[13][26][27] This issue belongs to the field of strategic rules: the question of which inferences need to be drawn to support one's conclusion. The distinction between definitory and strategic rules is not exclusive to logic: it is also found in various games.[13][26][27] In chess, for example, the definitory rules state that bishops may only move diagonally while the strategic rules recommend that one should control the center and protect one's king if one intends to win. In this sense, definitory rules determine whether one plays chess or something else whereas strategic rules determine whether one is a good or a bad chess player.[13][26] The same applies to deductive reasoning: to be an effective reasoner involves mastering both definitory and strategic rules.[13]

Validity and soundness

[edit]

Deductive arguments are evaluated in terms of their validity and soundness.

An argument is valid if it is impossible for its premises to be true while its conclusion is false. In other words, the conclusion must be true if the premises are true. An argument can be "valid" even if one or more of its premises are false.

An argument is sound if it is valid and the premises are true.

It is possible to have a deductive argument that is logically valid but is not sound. Fallacious arguments often take that form.

The following is an example of an argument that is "valid", but not "sound":

- Everyone who eats carrots is a quarterback.

- John eats carrots.

- Therefore, John is a quarterback.

The example's first premise is false – there are people who eat carrots who are not quarterbacks – but the conclusion would necessarily be true, if the premises were true. In other words, it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false. Therefore, the argument is "valid", but not "sound". False generalizations – such as "Everyone who eats carrots is a quarterback" – are often used to make unsound arguments. The fact that there are some people who eat carrots but are not quarterbacks proves the flaw of the argument.

In this example, the first statement uses categorical reasoning, saying that all carrot-eaters are definitely quarterbacks. This theory of deductive reasoning – also known as term logic – was developed by Aristotle, but was superseded by propositional (sentential) logic and predicate logic. [citation needed]

Deductive reasoning can be contrasted with inductive reasoning, in regards to validity and soundness. In cases of inductive reasoning, even though the premises are true and the argument is "valid", it is possible for the conclusion to be false (determined to be false with a counterexample or other means).

Difference from ampliative reasoning

[edit]Deductive reasoning is usually contrasted with non-deductive or ampliative reasoning.[13][28][29] The hallmark of valid deductive inferences is that it is impossible for their premises to be true and their conclusion to be false. In this way, the premises provide the strongest possible support to their conclusion.[13][28][29] The premises of ampliative inferences also support their conclusion. But this support is weaker: they are not necessarily truth-preserving. So even for correct ampliative arguments, it is possible that their premises are true and their conclusion is false.[11] Two important forms of ampliative reasoning are inductive and abductive reasoning.[30] Sometimes the term "inductive reasoning" is used in a very wide sense to cover all forms of ampliative reasoning.[11] However, in a more strict usage, inductive reasoning is just one form of ampliative reasoning.[30] In the narrow sense, inductive inferences are forms of statistical generalization. They are usually based on many individual observations that all show a certain pattern. These observations are then used to form a conclusion either about a yet unobserved entity or about a general law.[31][32][33] For abductive inferences, the premises support the conclusion because the conclusion is the best explanation of why the premises are true.[30][34]

The support ampliative arguments provide for their conclusion comes in degrees: some ampliative arguments are stronger than others.[11][35][30] This is often explained in terms of probability: the premises make it more likely that the conclusion is true.[13][28][29] Strong ampliative arguments make their conclusion very likely, but not absolutely certain. An example of ampliative reasoning is the inference from the premise "every raven in a random sample of 3200 ravens is black" to the conclusion "all ravens are black": the extensive random sample makes the conclusion very likely, but it does not exclude that there are rare exceptions.[35] In this sense, ampliative reasoning is defeasible: it may become necessary to retract an earlier conclusion upon receiving new related information.[12][30] Ampliative reasoning is very common in everyday discourse and the sciences.[13][36]

An important drawback of deductive reasoning is that it does not lead to genuinely new information.[5] This means that the conclusion only repeats information already found in the premises. Ampliative reasoning, on the other hand, goes beyond the premises by arriving at genuinely new information.[13][28][29] One difficulty for this characterization is that it makes deductive reasoning appear useless: if deduction is uninformative, it is not clear why people would engage in it and study it.[13][37] It has been suggested that this problem can be solved by distinguishing between surface and depth information. On this view, deductive reasoning is uninformative on the depth level, in contrast to ampliative reasoning. But it may still be valuable on the surface level by presenting the information in the premises in a new and sometimes surprising way.[13][5]

A popular misconception of the relation between deduction and induction identifies their difference on the level of particular and general claims.[2][9][38] On this view, deductive inferences start from general premises and draw particular conclusions, while inductive inferences start from particular premises and draw general conclusions. This idea is often motivated by seeing deduction and induction as two inverse processes that complement each other: deduction is top-down while induction is bottom-up. But this is a misconception that does not reflect how valid deduction is defined in the field of logic: a deduction is valid if it is impossible for its premises to be true while its conclusion is false, independent of whether the premises or the conclusion are particular or general.[2][9][1][5][3] Because of this, some deductive inferences have a general conclusion and some also have particular premises.[2]

In various fields

[edit]Cognitive psychology

[edit]Cognitive psychology studies the psychological processes responsible for deductive reasoning.[3][5] It is concerned, among other things, with how good people are at drawing valid deductive inferences. This includes the study of the factors affecting their performance, their tendency to commit fallacies, and the underlying biases involved.[3][5] A notable finding in this field is that the type of deductive inference has a significant impact on whether the correct conclusion is drawn.[3][5][39][40] In a meta-analysis of 65 studies, for example, 97% of the subjects evaluated modus ponens inferences correctly, while the success rate for modus tollens was only 72%. On the other hand, even some fallacies like affirming the consequent or denying the antecedent were regarded as valid arguments by the majority of the subjects.[3] An important factor for these mistakes is whether the conclusion seems initially plausible: the more believable the conclusion is, the higher the chance that a subject will mistake a fallacy for a valid argument.[3][5]

An important bias is the matching bias, which is often illustrated using the Wason selection task.[5][3][41][42] In an often-cited experiment by Peter Wason, four cards are presented to the participant. In one case, the visible sides show the symbols D, K, 5, and 7 on the different cards. The participant is told that every card has a letter on one side and a number on the other side, and that "[e]very card which has a D on one side has a 5 on the other side". Their task is to identify which cards need to be turned around in order to confirm or refute this conditional claim. The correct answer, only given by about 10%, is the cards D and 7. Many select card 5 instead, even though the conditional claim does not involve any requirements on what symbols can be found on the opposite side of card 5.[3][5] But this result can be drastically changed if different symbols are used: the visible sides show "drinking a beer", "drinking a coke", "16 years of age", and "22 years of age" and the participants are asked to evaluate the claim "[i]f a person is drinking beer, then the person must be over 19 years of age". In this case, 74% of the participants identified correctly that the cards "drinking a beer" and "16 years of age" have to be turned around.[3][5] These findings suggest that the deductive reasoning ability is heavily influenced by the content of the involved claims and not just by the abstract logical form of the task: the more realistic and concrete the cases are, the better the subjects tend to perform.[3][5]

Another bias is called the "negative conclusion bias", which happens when one of the premises has the form of a negative material conditional,[5][43][44] as in "If the card does not have an A on the left, then it has a 3 on the right. The card does not have a 3 on the right. Therefore, the card has an A on the left". The increased tendency to misjudge the validity of this type of argument is not present for positive material conditionals, as in "If the card has an A on the left, then it has a 3 on the right. The card does not have a 3 on the right. Therefore, the card does not have an A on the left".[5]

Psychological theories of deductive reasoning

[edit]Various psychological theories of deductive reasoning have been proposed. These theories aim to explain how deductive reasoning works in relation to the underlying psychological processes responsible. They are often used to explain the empirical findings, such as why human reasoners are more susceptible to some types of fallacies than to others.[3][1][45]

An important distinction is between mental logic theories, sometimes also referred to as rule theories, and mental model theories. Mental logic theories see deductive reasoning as a language-like process that happens through the manipulation of representations.[3][1][46][45] This is done by applying syntactic rules of inference in a way very similar to how systems of natural deduction transform their premises to arrive at a conclusion.[45] On this view, some deductions are simpler than others since they involve fewer inferential steps.[3] This idea can be used, for example, to explain why humans have more difficulties with some deductions, like the modus tollens, than with others, like the modus ponens: because the more error-prone forms do not have a native rule of inference but need to be calculated by combining several inferential steps with other rules of inference. In such cases, the additional cognitive labor makes the inferences more open to error.[3]

Mental model theories, on the other hand, hold that deductive reasoning involves models or mental representations of possible states of the world without the medium of language or rules of inference.[3][1][45] In order to assess whether a deductive inference is valid, the reasoner mentally constructs models that are compatible with the premises of the inference. The conclusion is then tested by looking at these models and trying to find a counterexample in which the conclusion is false. The inference is valid if no such counterexample can be found.[3][1][45] In order to reduce cognitive labor, only such models are represented in which the premises are true. Because of this, the evaluation of some forms of inference only requires the construction of very few models while for others, many different models are necessary. In the latter case, the additional cognitive labor required makes deductive reasoning more error-prone, thereby explaining the increased rate of error observed.[3][1] This theory can also explain why some errors depend on the content rather than the form of the argument. For example, when the conclusion of an argument is very plausible, the subjects may lack the motivation to search for counterexamples among the constructed models.[3]

Both mental logic theories and mental model theories assume that there is one general-purpose reasoning mechanism that applies to all forms of deductive reasoning.[3][46][47] But there are also alternative accounts that posit various different special-purpose reasoning mechanisms for different contents and contexts. In this sense, it has been claimed that humans possess a special mechanism for permissions and obligations, specifically for detecting cheating in social exchanges. This can be used to explain why humans are often more successful in drawing valid inferences if the contents involve human behavior in relation to social norms.[3] Another example is the so-called dual-process theory.[5][3] This theory posits that there are two distinct cognitive systems responsible for reasoning. Their interrelation can be used to explain commonly observed biases in deductive reasoning. System 1 is the older system in terms of evolution. It is based on associative learning and happens fast and automatically without demanding many cognitive resources.[5][3] System 2, on the other hand, is of more recent evolutionary origin. It is slow and cognitively demanding, but also more flexible and under deliberate control.[5][3] The dual-process theory posits that system 1 is the default system guiding most of our everyday reasoning in a pragmatic way. But for particularly difficult problems on the logical level, system 2 is employed. System 2 is mostly responsible for deductive reasoning.[5][3]

Intelligence

[edit]The ability of deductive reasoning is an important aspect of intelligence and many tests of intelligence include problems that call for deductive inferences.[1] Because of this relation to intelligence, deduction is highly relevant to psychology and the cognitive sciences.[5] But the subject of deductive reasoning is also pertinent to the computer sciences, for example, in the creation of artificial intelligence.[1]

Epistemology

[edit]Deductive reasoning plays an important role in epistemology. Epistemology is concerned with the question of justification, i.e. to point out which beliefs are justified and why.[48][49] Deductive inferences are able to transfer the justification of the premises onto the conclusion.[3] So while logic is interested in the truth-preserving nature of deduction, epistemology is interested in the justification-preserving nature of deduction. There are different theories trying to explain why deductive reasoning is justification-preserving.[3] According to reliabilism, this is the case because deductions are truth-preserving: they are reliable processes that ensure a true conclusion given the premises are true.[3][50][51] Some theorists hold that the thinker has to have explicit awareness of the truth-preserving nature of the inference for the justification to be transferred from the premises to the conclusion. One consequence of such a view is that, for young children, this deductive transference does not take place since they lack this specific awareness.[3]

Probability logic

[edit]Probability logic is interested in how the probability of the premises of an argument affects the probability of its conclusion. It differs from classical logic, which assumes that propositions are either true or false but does not take into consideration the probability or certainty that a proposition is true or false.[52][53]

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2015) |

Aristotle, a Greek philosopher, started documenting deductive reasoning in the 4th century BC.[54] René Descartes, in his book Discourse on Method, refined the idea for the Scientific Revolution. Developing four rules to follow for proving an idea deductively, Descartes laid the foundation for the deductive portion of the scientific method. Descartes' background in geometry and mathematics influenced his ideas on the truth and reasoning, causing him to develop a system of general reasoning now used for most mathematical reasoning. Similar to postulates, Descartes believed that ideas could be self-evident and that reasoning alone must prove that observations are reliable. These ideas also lay the foundations for the ideas of rationalism.[55]

Related concepts and theories

[edit]Deductivism

[edit]Deductivism is a philosophical position that gives primacy to deductive reasoning or arguments over their non-deductive counterparts.[56][57] It is often understood as the evaluative claim that only deductive inferences are good or correct inferences. This theory would have wide-reaching consequences for various fields since it implies that the rules of deduction are "the only acceptable standard of evidence".[56] This way, the rationality or correctness of the different forms of inductive reasoning is denied.[57][58] Some forms of deductivism express this in terms of degrees of reasonableness or probability. Inductive inferences are usually seen as providing a certain degree of support for their conclusion: they make it more likely that their conclusion is true. Deductivism states that such inferences are not rational: the premises either ensure their conclusion, as in deductive reasoning, or they do not provide any support at all.[59]

One motivation for deductivism is the problem of induction introduced by David Hume. It consists in the challenge of explaining how or whether inductive inferences based on past experiences support conclusions about future events.[57][60][59] For example, a chicken comes to expect, based on all its past experiences, that the person entering its coop is going to feed it, until one day the person "at last wrings its neck instead".[61] According to Karl Popper's falsificationism, deductive reasoning alone is sufficient. This is due to its truth-preserving nature: a theory can be falsified if one of its deductive consequences is false.[62][63] So while inductive reasoning does not offer positive evidence for a theory, the theory still remains a viable competitor until falsified by empirical observation. In this sense, deduction alone is sufficient for discriminating between competing hypotheses about what is the case.[57] Hypothetico-deductivism is a closely related scientific method, according to which science progresses by formulating hypotheses and then aims to falsify them by trying to make observations that run counter to their deductive consequences.[64][65]

Natural deduction

[edit]The term "natural deduction" refers to a class of proof systems based on self-evident rules of inference.[66][67] The first systems of natural deduction were developed by Gerhard Gentzen and Stanislaw Jaskowski in the 1930s. The core motivation was to give a simple presentation of deductive reasoning that closely mirrors how reasoning actually takes place.[68] In this sense, natural deduction stands in contrast to other less intuitive proof systems, such as Hilbert-style deductive systems, which employ axiom schemes to express logical truths.[66] Natural deduction, on the other hand, avoids axioms schemes by including many different rules of inference that can be used to formulate proofs. These rules of inference express how logical constants behave. They are often divided into introduction rules and elimination rules. Introduction rules specify under which conditions a logical constant may be introduced into a new sentence of the proof.[66][67] For example, the introduction rule for the logical constant "" (and) is "". It expresses that, given the premises "" and "" individually, one may draw the conclusion "" and thereby include it in one's proof. This way, the symbol "" is introduced into the proof. The removal of this symbol is governed by other rules of inference, such as the elimination rule "", which states that one may deduce the sentence "" from the premise "". Similar introduction and elimination rules are given for other logical constants, such as the propositional operator "", the propositional connectives "" and "", and the quantifiers "" and "".[66][67]

The focus on rules of inferences instead of axiom schemes is an important feature of natural deduction.[66][67] But there is no general agreement on how natural deduction is to be defined. Some theorists hold that all proof systems with this feature are forms of natural deduction. This would include various forms of sequent calculi[a] or tableau calculi. But other theorists use the term in a more narrow sense, for example, to refer to the proof systems developed by Gentzen and Jaskowski. Because of its simplicity, natural deduction is often used for teaching logic to students.[66]

Geometrical method

[edit]The geometrical method is a method of philosophy based on deductive reasoning. It starts from a small set of self-evident axioms and tries to build a comprehensive logical system based only on deductive inferences from these first axioms.[69] It was initially formulated by Baruch Spinoza and came to prominence in various rationalist philosophical systems in the modern era.[70] It gets its name from the forms of mathematical demonstration found in traditional geometry, which are usually based on axioms, definitions, and inferred theorems.[71][72] An important motivation of the geometrical method is to repudiate philosophical skepticism by grounding one's philosophical system on absolutely certain axioms. Deductive reasoning is central to this endeavor because of its necessarily truth-preserving nature. This way, the certainty initially invested only in the axioms is transferred to all parts of the philosophical system.[69]

One recurrent criticism of philosophical systems build using the geometrical method is that their initial axioms are not as self-evident or certain as their defenders proclaim.[69] This problem lies beyond the deductive reasoning itself, which only ensures that the conclusion is true if the premises are true, but not that the premises themselves are true. For example, Spinoza's philosophical system has been criticized this way based on objections raised against the causal axiom, i.e. that "the knowledge of an effect depends on and involves knowledge of its cause".[73] A different criticism targets not the premises but the reasoning itself, which may at times implicitly assume premises that are themselves not self-evident.[69]

See also

[edit]- Abductive reasoning – Inference seeking the simplest and most likely explanation

- Analogical reasoning – Cognitive process of transferring information or meaning from a particular subject to another

- Argument (logic) – Attempt to persuade or to determine the truth of a conclusion

- Argumentation theory – Academic field of logic and rhetoric

- Case-based reasoning – Process of solving new problems based on the solutions of similar past problems

- Correlation does not imply causation – Refutation of a logical fallacy

- Correspondence theory of truth – Theory that truth means correspondence with reality

- Decision making – Process to choose a course of action

- Decision theory – Branch of applied probability theory

- Defeasible reasoning – Reasoning that is rationally compelling, though not deductively valid

- Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence – Evidentiary standard for extraordinary claims

- Fallacy – Argument that uses faulty reasoning

- Fault tree analysis – Failure analysis system used in safety engineering and reliability engineering

- Geometry – Branch of mathematics

- Hypothetico-deductive method – Proposed description of the scientific method

- Inductive reasoning – Method of logical reasoning

- Inference – Steps in reasoning

- Inquiry – Any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem

- Legal syllogism – Form of argument to test if an act is lawful

- Logic and rationality – Fundamental concepts in philosophy

- Logical consequence – Relationship where one statement follows from another

- Logical reasoning – Process of drawing correct inferences

- Mathematical logic – Subfield of mathematics

- Natural deduction – Kind of proof calculus

- Peirce's theory of deductive reasoning – Theorem deduced from a more notable theorem

- Propositional calculus – Branch of logic

- Retroductive reasoning – Inference seeking the simplest and most likely explanation

- Scientific method – Interplay between observation, experiment, and theory in science

- Syllogism – Type of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning

- Subjective logic – Type of probabilistic logic

- Theory of justification – Concept in epistemology

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ In natural deduction, a simplified sequent consists of an environment that yields () a single conclusion ; a single sequent would take the form

- "Assumptions A1, A2, A3 etc. yield Conclusion C1"; in the symbols of natural deduction,

- However if the premises were true but the conclusion were false, a hidden assumption could be intervening; alternatively, a hidden process might be coercing the form of presentation, and so forth; then the task would be to unearth the hidden factors in an ill-formed syllogism, in order to make the form valid.

- see Deduction theorem

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Johnson-Laird, Phil (30 December 2009). "Deductive reasoning". WIREs Cognitive Science. 1 (1): 8–17. doi:10.1002/wcs.20. ISSN 1939-5078. PMID 26272833.

- ^ a b c d Houde, R. "Deduction". New Catholic Encyclopedia.

Modern logicians sometimes oppose deduction to induction on the basis that the first concludes from the general to the particular, whereas the second concludes from the particular to the general; this characterization is inaccurate, however, since deduction need not conclude to the particular and its process is far from being the logical inverse of the inductive procedure.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Schechter, Joshua (2013). "Deductive Reasoning". The Encyclopedia of the Mind. SAGE Reference. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Norris, Stephen E. (1975). "The Intelligibility of Practical Reasoning". American Philosophical Quarterly. 12 (1): 77–84. ISSN 0003-0481. JSTOR 20009561.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Evans, Jonathan (18 April 2005). "Deductive reasoning". In Morrison, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82417-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l McKeon, Matthew. "Logical Consequence". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Tarski, Alfred (1983). "On The Concept of Logical Consequence". Logic, Semantics, Metamathematics: Papers from 1923 to 1938. Hackett. ISBN 978-0-915-14476-1.

- ^ a b c d Vorobej, Mark (1992). "Defining Deduction". Informal Logic. 14 (2). doi:10.22329/il.v14i2.2533.

- ^ a b c d Wilbanks, Jan J. (2010). "Defining Deduction, Induction, and Validity". Argumentation. 24 (1): 107–124. doi:10.1007/s10503-009-9131-5. S2CID 144481717.

- ^ Copi, Irving M.; Cohen, Carl; Rodych, Victor (3 September 2018). "1. Basic Logical Concepts". Introduction to Logic. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-38696-8.

- ^ a b c d IEP Staff. "Deductive and Inductive Arguments". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Philosophy of logic". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Jaakko, Hintikka; Sandu, Gabriel (2006). "What is Logic?". Philosophy of Logic. North Holland. pp. 13–39.

- ^ a b c d Stump, David J. "Fallacy, Logical". New Dictionary of the History of Ideas.

- ^ Craig, Edward (1996). "Formal and informal logic". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge.

- ^ MacFarlane, John (2017). "Logical Constants". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Shieh, Sanford (2006). "LOGICAL KNOWLEDGE". In Borchert, Donald (ed.). Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 2nd Edition. Macmillan.

- ^ a b c Dowden, Bradley. "Fallacies". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Moschovakis, Joan (2021). "Intuitionistic Logic: 1. Rejection of Tertium Non Datur". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ Borchert, Donald (2006). "Logic, Non-Classical". Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 2nd. Macmillan.

- ^ Morreau, Michael (2009). "The Hypothetical Syllogism". Journal of Philosophical Logic. 38 (4): 447–464. doi:10.1007/s10992-008-9098-y. ISSN 0022-3611. JSTOR 40344073. S2CID 34804481.

- ^ Hansen, Hans (2020). "Fallacies". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Expert thinking and novice thinking: Deduction". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Thought". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ Stone, Mark A. (2012). "Denying the Antecedent: Its Effective Use in Argumentation". Informal Logic. 32 (3): 327–356. doi:10.22329/il.v32i3.3681.

- ^ a b c "Logical systems". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ a b Pedemonte, Bettina (25 June 2018). "Strategic vs Definitory Rules: Their Role in Abductive Argumentation and their Relationship with Deductive Proof". Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education. 14 (9): em1589. doi:10.29333/ejmste/92562. ISSN 1305-8215. S2CID 126245285.

- ^ a b c d Backmann, Marius (1 June 2019). "Varieties of Justification—How (Not) to Solve the Problem of Induction". Acta Analytica. 34 (2): 235–255. doi:10.1007/s12136-018-0371-6. ISSN 1874-6349. S2CID 125767384.

- ^ a b c d "Deductive and Inductive Arguments". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Douven, Igor (2021). "Abduction". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Borchert, Donald (2006). "G. W. Liebnitz". Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Macmillan.

- ^ Scott, John; Marshall, Gordon (2009). "Analytic induction". A Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-53300-8.

- ^ Houde, R.; Camacho, L. "Induction". New Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ Koslowski, Barbara (2017). "Abductive reasoning and explanation". International Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315725697-20 (inactive 1 July 2025). ISBN 978-1-315-72569-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ a b Hawthorne, James (2021). "Inductive Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Bunge, Mario (1960). "The Place of Induction in Science". Philosophy of Science. 27 (3): 262–270. doi:10.1086/287745. ISSN 0031-8248. JSTOR 185969. S2CID 120566417.

- ^ D'Agostino, Marcello; Floridi, Luciano (2009). "The Enduring Scandal of Deduction: Is Propositional Logic Really Uninformative?". Synthese. 167 (2): 271–315. doi:10.1007/s11229-008-9409-4. hdl:2299/2995. ISSN 0039-7857. JSTOR 40271192. S2CID 9602882.

- ^ "Deductive and Inductive Arguments". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Rips, Lance J. (1983). "Cognitive processes in propositional reasoning". Psychological Review. 90 (1): 38–71. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.90.1.38. ISSN 1939-1471. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Müller, Ulrich; Overton, Willis F.; Reene, Kelly (February 2001). "Development of Conditional Reasoning: A Longitudinal Study". Journal of Cognition and Development. 2 (1): 27–49. doi:10.1207/S15327647JCD0201_2. S2CID 143955563.

- ^ Evans, J. St B. T.; Lynch, J. S. (August 1973). "Matching Bias in the Selection Task". British Journal of Psychology. 64 (3): 391–397. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1973.tb01365.x.

- ^ Wagner-Egger, Pascal (1 October 2007). "Conditional reasoning and the Wason selection task: Biconditional interpretation instead of reasoning bias". Thinking & Reasoning. 13 (4): 484–505. doi:10.1080/13546780701415979. ISSN 1354-6783. S2CID 145011175.

- ^ Chater, Nick; Oaksford, Mike; Hahn, Ulrike; Heit, Evan (2011). "Inductive Logic and Empirical Psychology". Inductive Logic. Handbook of the History of Logic. Vol. 10. North-Holland. pp. 553–624. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52936-7.50014-8. ISBN 978-0-444-52936-7.

- ^ Arreckx, Frederique (2007). "Experiment 1: Affirmative and negative counterfactual questions". Counterfactual Thinking and the False Belief Task: A Developmental Study (Thesis). University of Plymouth. doi:10.24382/4506. hdl:10026.1/1758.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson-Laird, Philip N.; Byrne, Ruth M. J. (1993). "Precis of Deduction". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 16 (2): 323–333. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00030260.

- ^ a b García-Madruga, Juan A.; Gutiérrez, Francisco; Carriedo, Nuria; Moreno, Sergio; Johnson-Laird, Philip N. (November 2002). "Mental Models in Deductive Reasoning". The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 5 (2): 125–140. doi:10.1017/s1138741600005904. PMID 12428479. S2CID 15293848.

- ^ Johnson-Laird, Philip N. (18 October 2010). "Mental models and human reasoning". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (43): 18243–18250. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012933107. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2972923. PMID 20956326.

- ^ "Epistemology". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Steup, Matthias; Neta, Ram (2020). "Epistemology". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Becker, Kelly. "Reliabilism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Goldman, Alvin; Beddor, Bob (2021). "Reliabilist Epistemology". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Adams, Ernest W. (13 October 1998). "Deduction and Probability: What Probability Logic Is About". A Primer of Probability Logic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-575-86066-4.

- ^ Hájek, Alan (2001). "Probability, Logic, and Probability Logic". The Blackwell Guide to Philosophical Logic. Blackwell. pp. 362–384.

- ^ Evans, Jonathan St. B. T.; Newstead, Stephen E.; Byrne, Ruth M. J., eds. (1993). Human Reasoning: The Psychology of Deduction (Repr. ed.). Psychology Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-863-77313-6. Retrieved 2015-01-26.

In one sense [...] one can see the psychology of deductive reasoning as being as old as the study of logic, which originated in the writings of Aristotle.

- ^ Samaha, Raid (3 March 2009). "Descartes' Project of Inquiry" (PDF). American University of Beirut. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ a b Bermejo-Luque, Lilian (2020). "What is Wrong with Deductivism?". Informal Logic. 40 (3): 295–316. doi:10.22329/il.v40i30.6214. S2CID 217418605.

- ^ a b c d Howson, Colin (2000). "Deductivism". Hume's Problem. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/0198250371.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-198-25037-1.

- ^ Kotarbinska, Janina (1977). "The Controversy: Deductivism Versus Inductivism". Twenty-Five Years of Logical Methodology in Poland. Springer Netherlands. pp. 261–278. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1126-6_15. ISBN 978-9-401-01126-6.

- ^ a b Stove, D. (1970). "Deductivism". Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 48 (1): 76–98. doi:10.1080/00048407012341481.

- ^ Henderson, Leah (2020). "The Problem of Induction". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2009) [1959]. "On Induction". The Problems of Philosophy – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Thornton, Stephen (2021). "Karl Popper: 4. Basic Statements, Falsifiability and Convention". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Shea, Brendan. "Popper, Karl: Philosophy of Science". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "hypothetico-deductive method". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "hypothetico-deductive method". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Indrzejczak, Andrzej. "Natural Deduction". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d Pelletier, Francis Jeffry; Hazen, Allen (2021). "Natural Deduction Systems in Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Gentzen, Gerhard (1934). "Untersuchungen über das logische Schließen. I". Mathematische Zeitschrift (in German). 39 (2): 176–210. doi:10.1007/BF01201353. S2CID 121546341.

Ich wollte nun zunächst einmal einen Formalismus aufstellen, der dem wirklichen Schließen möglichst nahe kommt. So ergab sich ein "Kalkül des natürlichen Schließens. (First I wished to construct a formalism that comes as close as possible to actual reasoning. Thus arose a "calculus of natural deduction".)

- ^ a b c d Daly, Chris (2015). "Introduction and Historical Overview". The Palgrave Handbook of Philosophical Methods. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–30. doi:10.1057/9781137344557_1. ISBN 978-1-137-34455-7.

- ^ Dutton, Blake D. "Spinoza, Benedict De". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Goldenbaum, Ursula. "Geometrical Method". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Nadler, Steven (2006). "The geometric method". Spinoza's 'Ethics': An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 35–51. ISBN 978-0-521-83620-3.

- ^ Doppelt, Torin (2010). "The Truth About 1A4". Spinoza's Causal Axiom: A Defense (PDF).

Further reading

[edit]- Vincent F. Hendricks, Thought 2 Talk: A Crash Course in Reflection and Expression, New York: Automatic Press / VIP, 2005, ISBN 87-991013-7-8

- Philip Johnson-Laird, Ruth M. J. Byrne, Deduction, Psychology Press 1991, ISBN 978-0-86377-149-1

- Zarefsky, David, Argumentation: The Study of Effective Reasoning Parts I and II, The Teaching Company 2002

- Bullemore, Thomas. The Pragmatic Problem of Induction.

External links

[edit]- Deductive reasoning at PhilPapers

- Deductive reasoning at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Fieser, James; Dowden, Bradley (eds.). "Deductive reasoning". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. OCLC 37741658.

Deductive reasoning

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Definition

Deductive reasoning is a form of logical inference that proceeds from general premises assumed to be true to derive specific conclusions that necessarily follow if those premises hold. In this top-down process, the truth of the premises guarantees the truth of the conclusion, making it a truth-preserving method of argumentation.[5][6] A classic example is the categorical syllogism: "All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal." This illustrates the basic syllogistic form, consisting of a major premise stating a general rule, a minor premise applying it to a specific case, and a conclusion that logically connects the two. Another propositional example is: "If it rains, the ground gets wet; it is raining; therefore, the ground gets wet." These structures ensure that the conclusion is entailed by the premises without additional assumptions.[6][7] Key characteristics of deductive reasoning include its validity, where the argument's structure alone preserves truth from premises to conclusion, and monotonicity, meaning that adding new premises cannot invalidate an existing valid conclusion—instead, it can only strengthen or expand the set of derivable conclusions. Unlike non-deductive forms, which allow for probable but not certain outcomes, deductive reasoning demands certainty within its assumed framework.[7][5]Conceptions of Deduction

Deductive reasoning has been conceptualized in various ways within philosophy and logic, reflecting different emphases on form, truth, and constructivity. The syntactic conception views deduction as the mechanical application of rules to manipulate symbols in a formal system, independent of their interpretation. The semantic conception, in contrast, defines deduction in terms of truth preservation across all possible interpretations or models. The proof-theoretic conception focuses on the constructive derivation of conclusions from premises, where meaning is given by the proofs themselves. These views are not mutually exclusive but highlight distinct aspects of deductive processes, with ongoing debates about whether deduction demands absolute certainty or allows for more flexible interpretations in certain logical frameworks. The syntactic conception treats deduction as a purely formal process of symbol manipulation governed by inference rules within a deductive system, such as axiomatic systems in first-order logic. In this view, a conclusion is deductively valid if it can be derived from the premises using a finite sequence of rule applications, without reference to the meaning or truth of the symbols involved. This approach, prominent in Hilbert-style formal systems, emphasizes the syntax or structure of arguments to ensure consistency and avoid paradoxes. For example, in propositional logic, modus ponens serves as a syntactic rule allowing the inference of from and , regardless of content. The semantic conception, formalized by Alfred Tarski, defines deduction through the relation of logical consequence, where a conclusion follows deductively from premises if it is true in every model (or interpretation) in which the premises are true. Tarski specified that logical consequence holds when no counterexample exists where the premises are satisfied but the conclusion is not, thus preserving truth semantically across all possible structures. This model-theoretic approach underpins classical logic's validity, ensuring that deductive inferences are necessarily truth-preserving given true premises.[8] The proof-theoretic conception, advanced by Michael Dummett and Dag Prawitz, understands deduction as the provision of constructive proofs that justify assertions, with the meaning of logical constants derived from their introduction and elimination rules in natural deduction systems. Here, a conclusion is deductively derivable if there exists a proof term witnessing its inference from the premises, emphasizing harmony between rules to avoid circularity. This view shifts focus from static truth conditions to dynamic proof construction, influencing justifications for inference in formal systems.[9] Debates persist over strict versus loose conceptions of deduction, particularly regarding whether it requires absolute certainty in all cases or permits high-probability preservation in non-classical settings. In strict views, aligned with classical logic, deduction guarantees the conclusion's truth if premises are true, excluding any uncertainty. Loose conceptions, however, allow for probabilistic or context-dependent inferences in logics like relevance logic, where strict truth preservation may not hold but conclusions remain highly reliable. These discussions challenge the universality of classical deduction, prompting reevaluations of certainty in logical inference.[10] Non-classical logics introduce variants of deduction, such as intuitionistic and modal forms. In intuitionistic logic, formalized by Arend Heyting, deduction rejects the law of excluded middle, requiring constructive proofs for existential claims rather than mere non-contradiction; a statement is true only if a proof of it can be exhibited. Modal deduction, developed through Saul Kripke's possible-worlds semantics, incorporates necessity and possibility operators, where inferences preserve truth across accessible worlds, allowing deductions about what must or might hold in varying epistemic or metaphysical contexts. These variants extend deductive reasoning beyond classical bounds while maintaining core inferential rigor.[11][12]Logical Mechanisms

Rules of Inference

Rules of inference constitute the foundational mechanisms in deductive reasoning, enabling the derivation of conclusions from given premises through systematic, step-by-step transformations within formal logical systems. These rules ensure that if the premises are true, the conclusion must necessarily follow, preserving the truth across inferences in systems like propositional logic.[13] Among the most prominent rules is modus ponens, which allows inference of from the premises and . Symbolically, this is expressed as . In natural language, if "all humans are mortal" and "Socrates is human," it follows that "Socrates is mortal."[14] Another key rule is modus tollens, permitting the inference of from and , or . For instance, if "if it rains, the ground gets wet" and "the ground is not wet," then "it did not rain."[13] Hypothetical syllogism, also called the chain rule, derives from and , symbolized as . An example is: if "studying leads to good grades" and "good grades lead to scholarships," then "studying leads to scholarships."[14] Other essential rules include disjunctive syllogism, which infers from and , or ; for example, "either the team wins or loses" and "the team did not win," so "the team lost."[13] Conjunction introduction combines two premises and to yield , as in inferring "it is raining and cold" from separate statements of each. Conjunction elimination extracts from , such as concluding "it is raining" from "it is raining and cold." These rules form a brief but core set for constructing arguments in propositional logic without exhaustive enumeration.[15]| Rule | Premises | Conclusion | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modus Ponens | , | If it rains, streets are wet; it rains → streets are wet. | |

| Modus Tollens | , | If it rains, streets are wet; streets are dry → it did not rain. | |

| Hypothetical Syllogism | , | Exercise leads to fitness; fitness leads to health → exercise leads to health. | |

| Disjunctive Syllogism | , | Either study or fail; did not study → will fail. | |

| Conjunction Introduction | , | It is sunny; it is warm → it is sunny and warm. | |

| Conjunction Elimination | It is sunny and warm → it is sunny. |

Validity and Soundness

In deductive logic, an argument is valid if its conclusion necessarily follows from its premises, meaning there exists no possible situation or interpretation in which the premises are true while the conclusion is false.[18] This structural property depends solely on the logical form of the argument, independent of the actual truth of the premises or the content of the statements involved.[19] Validity can be formally tested using semantic methods, such as model theory, where a model assigns interpretations to the non-logical elements (e.g., predicates and constants) over a domain, and the argument is valid if every model satisfying the premises also satisfies the conclusion.[20] Alternatively, syntactic methods involve deriving the conclusion from the premises using a formal proof system of inference rules, confirming validity through step-by-step deduction.[20] For propositional logic, truth tables provide a straightforward semantic test for validity by enumerating all possible truth-value assignments to the atomic propositions and checking whether any assignment renders all premises true and the conclusion false.[21] Consider the argument with premises and , concluding (modus tollens):| T | T | T | F | F |

| T | F | F | T | F |

| F | T | T | F | T |

| F | F | T | T | T |

Comparisons with Other Forms of Reasoning

Differences from Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up process that involves inferring general principles or rules from specific observations or particulars, often leading to probabilistic conclusions that extend beyond the given data.[22] For instance, observing that the sun has risen every day in recorded history might lead to the generalization that it will rise tomorrow, representing a form of enumerative induction.[23] Unlike deductive reasoning, inductive inferences are non-monotonic, meaning that adding new evidence can undermine previously drawn conclusions, and they are inherently fallible, as no amount of confirmatory instances guarantees the truth of the generalization.[22] A fundamental difference between deductive and inductive reasoning lies in their logical structure and reliability: deductive reasoning preserves truth, such that if the premises are true and the argument is valid, the conclusion must be true, ensuring certainty within the given framework.[5] In contrast, inductive reasoning amplifies information by drawing broader conclusions from limited data but carries an inherent risk of error, as the conclusion is only probable and not guaranteed, even if supported by strong evidence.[22] This makes deduction non-ampliative—it does not introduce new content beyond the premises—while induction is ampliative, generating hypotheses that go beyond what is explicitly stated.[5] The strength of deductive arguments is assessed through all-or-nothing validity, where an argument is either fully valid or invalid based on whether the conclusion logically follows from the premises.[22] For inductive reasoning, strength is measured by degrees of confirmation or support, often formalized using Bayesian approaches, where the posterior probability of a hypothesis given evidence is calculated as with denoting the probability of hypothesis given evidence , the likelihood of the evidence under the hypothesis, the prior probability, and the total probability of the evidence.[22] This probabilistic framework highlights induction's reliance on updating beliefs incrementally, unlike deduction's binary certainty.[22] To illustrate, a classic deductive syllogism states: "All humans are mortal; Socrates is human; therefore, Socrates is mortal," where the conclusion is necessarily true if the premises hold, demonstrating truth preservation.[5] An inductive example, such as observing multiple black ravens and concluding that all ravens are black, relies on enumerative induction but remains open to falsification by a single non-black raven, showing the probabilistic nature without overlap into hybrid forms like inference to the best explanation in this context.[5] Philosophically, the paradoxes of induction, such as those articulated by Carl Hempel, underscore the challenges of inductive certainty, as seemingly irrelevant evidence (e.g., observing a white shoe confirming "all ravens are black") can paradoxically support generalizations under equivalence conditions, contrasting sharply with the unassailable logical structure of deduction.[24] These paradoxes highlight induction's vulnerability to counterintuitive confirmations, reinforcing deduction's role in providing reliable, non-probabilistic foundations for knowledge.[24]Differences from Abductive Reasoning

Abductive reasoning, also known as inference to the best explanation, is the process of selecting a hypothesis that, if true, would best account for a given set of observed facts.[25] This form of inference was coined by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce in the late 19th century as part of his work on the logic of science, where he distinguished it from deduction and induction as a creative process for generating explanatory hypotheses.[26] For example, observing wet grass on a lawn leads to the abduction that it rained overnight, as this hypothesis explains the observation more plausibly than alternatives like a sprinkler, assuming no contradictory evidence.[25] A fundamental difference between deductive and abductive reasoning lies in their direction and certainty. Deductive reasoning proceeds forward from general premises to derive necessary conclusions that are entailed by those premises, ensuring that if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true.[25] In contrast, abductive reasoning operates backward from an observed effect to a probable cause or hypothesis, making it inherently creative, tentative, and defeasible—meaning the inferred hypothesis can be overturned by new evidence.[25] While deduction is non-ampliative, merely explicating information already contained in the premises without adding new content, abduction is ampliative, introducing novel ideas to explain phenomena.[25] The logical form of abductive reasoning, as articulated by Peirce, can be schematized as follows: a surprising fact C is observed; but if hypothesis A were true, C would be a matter of course; therefore, there is reason to suspect that A is true.[25] This structure highlights abduction's role in hypothesis formation, where the conclusion is probabilistic rather than certain. In abductive reasoning, the "best" explanation is evaluated based on criteria such as simplicity (favoring hypotheses with fewer assumptions), coherence (consistency with existing knowledge), and explanatory or predictive power (ability to account for the data and anticipate further observations).[27] These qualities underscore abduction's ampliative and fallible nature, differing sharply from deduction's reliance on formal validity and soundness, which guarantee truth preservation without regard to explanatory depth or novelty.[25] Illustrative examples highlight these distinctions. In medical diagnosis, abductive reasoning is employed when symptoms (e.g., fever and cough) lead to inferring a probable cause like pneumonia, as it best explains the observations among competing hypotheses, though further tests may revise it.[26] Conversely, deductive reasoning dominates in theorem proving, such as deriving that there are infinitely many prime numbers (Euclid's theorem) from basic axioms of arithmetic via proof by contradiction, yielding a necessarily true conclusion without introducing new empirical content.[25][28]Applications Across Disciplines

In Cognitive Psychology

In cognitive psychology, deductive reasoning is understood through several prominent theories that explain how humans mentally process logical inferences. Mental logic theory posits that deduction relies on an innate, rule-based system analogous to formal logic, where individuals apply syntactic rules to premises to derive conclusions. Lance J. Rips developed this framework in his PSYCII model, which simulates human deduction using inference rules like modus ponens and denial of the antecedent, supported by experimental evidence showing systematic performance patterns in syllogistic tasks.[29] In contrast, the mental models theory, proposed by Philip N. Johnson-Laird, argues that reasoners construct iconic, diagrammatic representations of possible scenarios based on premises and general knowledge, then eliminate inconsistent models to reach conclusions; this accounts for errors in multi-premise inferences where multiple models complicate visualization.[30] Dual-process theories integrate these by distinguishing System 1 (fast, intuitive, heuristic-based processing prone to biases) from System 2 (slow, analytical, rule- or model-based deduction requiring effortful engagement), with empirical support from tasks showing quicker but error-prone intuitive responses shifting to accurate analytical ones under instruction.[31] Developmental research highlights how deductive abilities emerge across childhood. Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive stages identifies the formal operational stage (around age 12 onward) as enabling abstract, hypothetical-deductive reasoning, where adolescents can manipulate propositions without concrete referents, as demonstrated in tasks involving if-then hypotheticals.[32] However, empirical tests like the Wason selection task reveal persistent challenges; in its abstract form, participants must select cards to falsify a conditional rule (e.g., "If vowel then even number"), yet success rates are as low as 19%, with approximately 80% failing to select the cards necessary for falsification by focusing on confirmation rather than disconfirmation, illustrating confirmation bias even in adults.[33] Deductive reasoning correlates with general intelligence (g-factor), serving as a key component alongside fluid and crystallized abilities, though not its sole indicator. Performance on deductive tasks predicts g, with correlations ranging from 0.25 to 0.45, and nonverbal tests like Raven's Progressive Matrices act as proxies by assessing pattern-based inference akin to deduction.[34] Neuroimaging studies link these abilities to prefrontal cortex activation; functional MRI (fMRI) scans show dorsolateral prefrontal cortex engagement during analytical deduction, supporting working memory and rule application.[35] Biases such as belief bias undermine deductive accuracy, where reasoners endorse invalid arguments if conclusions align with prior beliefs, overriding logical validity. This effect, robust across syllogisms, stems from System 1 interference and is mitigated by analytical effort. Recent post-2020 fMRI research on belief-bias reasoning identifies heightened anterior cingulate cortex activity for conflict detection in biased trials, alongside prefrontal recruitment to suppress intuitive endorsements, predicting critical thinking proficiency.[36]In Philosophy and Epistemology