Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rationalism

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Epistemology |

|---|

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge"[1] or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge",[2] often in contrast to other possible sources of knowledge such as faith, tradition, or sensory experience. More formally, rationalism is defined as a methodology or a theory "in which the criterion of truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive".[3]

In a major philosophical debate during the Enlightenment,[4] rationalism (sometimes here equated with innatism) was opposed to empiricism. On the one hand, rationalists like René Descartes emphasized that knowledge is primarily innate and the intellect, the inner faculty of the human mind, can therefore directly grasp or derive logical truths; on the other hand, empiricists like John Locke emphasized that knowledge is not primarily innate and is best gained by careful observation of the physical world outside the mind, namely through sensory experiences. Rationalists asserted that certain principles exist in logic, mathematics, ethics, and metaphysics that are so fundamentally true that denying them causes one to fall into contradiction. The rationalists had such a high confidence in reason that empirical proof and physical evidence were regarded as unnecessary to ascertain certain truths – in other words, "there are significant ways in which our concepts and knowledge are gained independently of sense experience".[5]

Different degrees of emphasis on this method or theory lead to a range of rationalist standpoints, from the moderate position "that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge" to the more extreme position that reason is "the unique path to knowledge".[2] Given a pre-modern understanding of reason, rationalism is identical to philosophy, the Socratic life of inquiry, or the zetetic (skeptical) clear interpretation of authority (open to the underlying or essential cause of things as they appear to our sense of certainty).

Background

[edit]Rationalism has a philosophical history dating from antiquity. The analytical nature of much of philosophical enquiry, the awareness of apparently a priori domains of knowledge such as mathematics, combined with the emphasis of obtaining knowledge through the use of rational faculties (commonly rejecting, for example, direct revelation) have made rationalist themes very prevalent in the history of philosophy.

Since the Enlightenment, rationalism is usually associated with the introduction of mathematical methods into philosophy as seen in the works of Descartes, Leibniz, and Spinoza.[3] This is commonly called continental rationalism, because it was predominant in the continental schools of Europe, whereas in Britain empiricism dominated.

Even then, the distinction between rationalists and empiricists was drawn at a later period and would not have been recognized by the philosophers involved. Also, the distinction between the two philosophies is not as clear-cut as is sometimes suggested; for example, Descartes and Locke have similar views about the nature of human ideas.[5]

Proponents of some varieties of rationalism argue that, starting with foundational basic principles, like the axioms of geometry, one could deductively derive the rest of all possible knowledge. Notable philosophers who held this view most clearly were Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, whose attempts to grapple with the epistemological and metaphysical problems raised by Descartes led to a development of the fundamental approach of rationalism. Both Spinoza and Leibniz asserted that, in principle, all knowledge, including scientific knowledge, could be gained through the use of reason alone, though they both observed that this was not possible in practice for human beings except in specific areas such as mathematics. On the other hand, Leibniz admitted in his book Monadology that "we are all mere Empirics in three fourths of our actions."[6]

Political usage

[edit]In politics, rationalism, since the Enlightenment, historically emphasized a "politics of reason" centered upon rationality, deontology, utilitarianism, secularism, and irreligion[7] – the latter aspect's antitheism was later softened by the adoption of pluralistic reasoning methods practicable regardless of religious or irreligious ideology.[8][9] In this regard, the philosopher John Cottingham[10] noted how rationalism, a methodology, became socially conflated with atheism, a worldview:

In the past, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, the term 'rationalist' was often used to refer to free thinkers of an anti-clerical and anti-religious outlook, and for a time the word acquired a distinctly pejorative force (thus in 1670 Sanderson spoke disparagingly of 'a mere rationalist, that is to say in plain English an atheist of the late edition...'). The use of the label 'rationalist' to characterize a world outlook which has no place for the supernatural is becoming less popular today; terms like 'humanist' or 'materialist' seem largely to have taken its place. But the old usage still survives.

Philosophical usage

[edit]Rationalism is often contrasted with empiricism. Taken very broadly, these views are not mutually exclusive, since – on some definitions – a philosopher can be both rationalist and empiricist.[11][2] Taken to extremes, the empiricist view holds that all ideas come to us a posteriori, that is to say, through experience; either through the external senses or through such inner sensations as pain and gratification. The empiricist essentially believes that knowledge is based on or derived directly from experience. The rationalist believes we come to knowledge a priori – through the use of logic – and is thus independent of sensory experience. In other words, as Galen Strawson once wrote, "you can see that it is true just lying on your couch. You don't have to get up off your couch and go outside and examine the way things are in the physical world. You don't have to do any science."[12]

Between both philosophies, the issue at hand is the fundamental source of human knowledge and the proper techniques for verifying what we think we know. Whereas both philosophies are under the umbrella of epistemology, their argument lies in the understanding of the warrant, which is under the wider epistemic umbrella of the theory of justification. Part of epistemology, this theory attempts to understand the justification of propositions and beliefs. Epistemologists are concerned with various epistemic features of belief, which include the ideas of justification, warrant, rationality, and probability. Of these four terms, the term that has been most widely used and discussed by the early 21st century is "warrant". Loosely speaking, justification is the reason that someone (probably) holds a belief.

If A makes a claim and then B casts doubt on it, A's next move would normally be to provide justification for the claim. The precise method one uses to provide justification is where the lines are drawn between rationalism and empiricism (among other philosophical views). Much of the debate in these fields are focused on analyzing the nature of knowledge and how it relates to connected notions such as truth, belief, and justification.

At its core, rationalism consists of three basic claims. For people to consider themselves rationalists, they must adopt at least one of these three claims: the intuition/deduction thesis, the innate knowledge thesis, or the innate concept thesis. In addition, a rationalist can choose to adopt the claim of Indispensability of Reason and or the claim of Superiority of Reason, although one can be a rationalist without adopting either thesis.[citation needed]

The indispensability of reason thesis: "The knowledge we gain in subject area, S, by intuition and deduction, as well as the ideas and instances of knowledge in S that are innate to us, could not have been gained by us through sense experience."[1] In short, this thesis claims that experience cannot provide what we gain from reason.

The superiority of reason thesis: '"The knowledge we gain in subject area S by intuition and deduction or have innately is superior to any knowledge gained by sense experience".[1] In other words, this thesis claims reason is superior to experience as a source for knowledge.

Rationalists often adopt similar stances on other aspects of philosophy. Most rationalists reject skepticism for the areas of knowledge they claim are knowable a priori. When you claim some truths are innately known to us, one must reject skepticism in relation to those truths. Especially for rationalists who adopt the Intuition/Deduction thesis, the idea of epistemic foundationalism tends to crop up. This is the view that we know some truths without basing our belief in them on any others and that we then use this foundational knowledge to know more truths.[1]

Intuition/deduction thesis

[edit]"Some propositions in a particular subject area, S, are knowable by us by intuition alone; still others are knowable by being deduced from intuited propositions."[13]

Generally speaking, intuition is a priori knowledge or experiential belief characterized by its immediacy; a form of rational insight. We simply "see" something in such a way as to give us a warranted belief. Beyond that, the nature of intuition is hotly debated. In the same way, generally speaking, deduction is the process of reasoning from one or more general premises to reach a logically certain conclusion. Using valid arguments, we can deduce from intuited premises.

For example, when we combine both concepts, we can intuit that the number three is prime and that it is greater than two. We then deduce from this knowledge that there is a prime number greater than two. Thus, it can be said that intuition and deduction combined to provide us with a priori knowledge – we gained this knowledge independently of sense experience.

To argue in favor of this thesis, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a prominent German philosopher, says,

The senses, although they are necessary for all our actual knowledge, are not sufficient to give us the whole of it, since the senses never give anything but instances, that is to say particular or individual truths. Now all the instances which confirm a general truth, however numerous they may be, are not sufficient to establish the universal necessity of this same truth, for it does not follow that what happened before will happen in the same way again. … From which it appears that necessary truths, such as we find in pure mathematics, and particularly in arithmetic and geometry, must have principles whose proof does not depend on instances, nor consequently on the testimony of the senses, although without the senses it would never have occurred to us to think of them…[14]

Empiricists such as David Hume have been willing to accept this thesis for describing the relationships among our own concepts.[13] In this sense, empiricists argue that we are allowed to intuit and deduce truths from knowledge that has been obtained a posteriori.

By injecting different subjects into the Intuition/Deduction thesis, we are able to generate different arguments. Most rationalists agree mathematics is knowable by applying the intuition and deduction. Some go further to include ethical truths into the category of things knowable by intuition and deduction. Furthermore, some rationalists also claim metaphysics is knowable in this thesis. Naturally, the more subjects the rationalists claim to be knowable by the Intuition/Deduction thesis, the more certain they are of their warranted beliefs, and the more strictly they adhere to the infallibility of intuition, the more controversial their truths or claims and the more radical their rationalism.[13]

In addition to different subjects, rationalists sometimes vary the strength of their claims by adjusting their understanding of the warrant. Some rationalists understand warranted beliefs to be beyond even the slightest doubt; others are more conservative and understand the warrant to be belief beyond a reasonable doubt.

Rationalists also have different understanding and claims involving the connection between intuition and truth. Some rationalists claim that intuition is infallible and that anything we intuit to be true is as such. More contemporary rationalists accept that intuition is not always a source of certain knowledge – thus allowing for the possibility of a deceiver who might cause the rationalist to intuit a false proposition in the same way a third party could cause the rationalist to have perceptions of nonexistent objects.

Innate knowledge thesis

[edit]"We have knowledge of some truths in a particular subject area, S, as part of our rational nature."[15]

The Innate Knowledge thesis is similar to the Intuition/Deduction thesis in the regard that both theses claim knowledge is gained a priori. The two theses go their separate ways when describing how that knowledge is gained. As the name, and the rationale, suggests, the Innate Knowledge thesis claims knowledge is simply part of our rational nature. Experiences can trigger a process that allows this knowledge to come into our consciousness, but the experiences do not provide us with the knowledge itself. The knowledge has been with us since the beginning and the experience simply brought into focus, in the same way a photographer can bring the background of a picture into focus by changing the aperture of the lens. The background was always there, just not in focus.

This thesis targets a problem with the nature of inquiry originally postulated by Plato in Meno. Here, Plato asks about inquiry; how do we gain knowledge of a theorem in geometry? We inquire into the matter. Yet, knowledge by inquiry seems impossible.[16] In other words, "If we already have the knowledge, there is no place for inquiry. If we lack the knowledge, we don't know what we are seeking and cannot recognize it when we find it. Either way we cannot gain knowledge of the theorem by inquiry. Yet, we do know some theorems."[15] The Innate Knowledge thesis offers a solution to this paradox. By claiming that knowledge is already with us, either consciously or unconsciously, a rationalist claims we don't really learn things in the traditional usage of the word, but rather that we simply use words we know.

Innate concept thesis

[edit]"We have some of the concepts we employ in a particular subject area, S, as part of our rational nature."[17]

Similar to the Innate Knowledge thesis, the Innate Concept thesis suggests that some concepts are simply part of our rational nature. These concepts are a priori in nature and sense experience is irrelevant to determining the nature of these concepts (though, sense experience can help bring the concepts to our conscious mind).

In his book Meditations on First Philosophy,[18] René Descartes postulates three classifications for our ideas when he says, "Among my ideas, some appear to be innate, some to be adventitious, and others to have been invented by me. My understanding of what a thing is, what truth is, and what thought is, seems to derive simply from my own nature. But my hearing a noise, as I do now, or seeing the sun, or feeling the fire, comes from things which are located outside me, or so I have hitherto judged. Lastly, sirens, hippogriffs and the like are my own invention."[19]

Adventitious ideas are those concepts that we gain through sense experiences, ideas such as the sensation of heat, because they originate from outside sources; transmitting their own likeness rather than something else and something you simply cannot will away. Ideas invented by us, such as those found in mythology, legends and fairy tales, are created by us from other ideas we possess. Lastly, innate ideas, such as our ideas of perfection, are those ideas we have as a result of mental processes that are beyond what experience can directly or indirectly provide.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz defends the idea of innate concepts by suggesting the mind plays a role in determining the nature of concepts, to explain this, he likens the mind to a block of marble in the New Essays on Human Understanding,

This is why I have taken as an illustration a block of veined marble, rather than a wholly uniform block or blank tablets, that is to say what is called tabula rasa in the language of the philosophers. For if the soul were like those blank tablets, truths would be in us in the same way as the figure of Hercules is in a block of marble, when the marble is completely indifferent whether it receives this or some other figure. But if there were veins in the stone which marked out the figure of Hercules rather than other figures, this stone would be more determined thereto, and Hercules would be as it were in some manner innate in it, although labour would be needed to uncover the veins, and to clear them by polishing, and by cutting away what prevents them from appearing. It is in this way that ideas and truths are innate in us, like natural inclinations and dispositions, natural habits or potentialities, and not like activities, although these potentialities are always accompanied by some activities which correspond to them, though they are often imperceptible."[20]

Some philosophers, such as John Locke (who is considered one of the most influential thinkers of the Enlightenment and an empiricist), argue that the Innate Knowledge thesis and the Innate Concept thesis are the same.[21] Other philosophers, such as Peter Carruthers, argue that the two theses are distinct from one another. As with the other theses covered under the umbrella of rationalism, the more types and greater number of concepts a philosopher claims to be innate, the more controversial and radical their position; "the more a concept seems removed from experience and the mental operations we can perform on experience the more plausibly it may be claimed to be innate. Since we do not experience perfect triangles but do experience pains, our concept of the former is a more promising candidate for being innate than our concept of the latter.[17]

History

[edit]Rationalist philosophy in Western antiquity

[edit]

Although rationalism in its modern form post-dates antiquity, philosophers from this time laid down the foundations of rationalism. In particular, the understanding that we may be aware of knowledge available only through the use of rational thought.[citation needed]

Pythagoras (570–495 BCE)

[edit]Pythagoras was one of the first Western philosophers to stress rationalist insight.[22] He is often revered as a great mathematician, mystic and scientist, but he is best known for the Pythagorean theorem, which bears his name, and for discovering the mathematical relationship between the length of strings on lute and the pitches of the notes. Pythagoras "believed these harmonies reflected the ultimate nature of reality. He summed up the implied metaphysical rationalism in the words 'All is number'. It is probable that he had caught the rationalist's vision, later seen by Galileo (1564–1642), of a world governed throughout by mathematically formulable laws".[23] It has been said that he was the first man to call himself a philosopher, or lover of wisdom.[24]

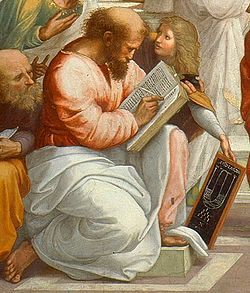

Plato (427–347 BCE)

[edit]

Plato held rational insight to a very high standard, as is seen in his works such as Meno and The Republic. He taught on the Theory of Forms (or the Theory of Ideas)[25][26][27] which asserts that the highest and most fundamental kind of reality is not the material world of change known to us through sensation, but rather the abstract, non-material (but substantial) world of forms (or ideas).[28] For Plato, these forms were accessible only to reason and not to sense.[23] In fact, it is said that Plato admired reason, especially in geometry, so highly that he had the phrase "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter" inscribed over the door to his academy.[29]

Aristotle (384–322 BCE)

[edit]Aristotle's main contribution to rationalist thinking was the use of syllogistic logic and its use in argument. Aristotle defines syllogism as "a discourse in which certain (specific) things having been supposed, something different from the things supposed results of necessity because these things are so."[30] Despite this very general definition, Aristotle limits himself to categorical syllogisms which consist of three categorical propositions in his work Prior Analytics.[31] These included categorical modal syllogisms.[32]

Middle Ages

[edit]

Although the three great Greek philosophers disagreed with one another on specific points, they all agreed that rational thought could bring to light knowledge that was self-evident – information that humans otherwise could not know without the use of reason. After Aristotle's death, Western rationalistic thought was generally characterized by its application to theology, such as in the works of Augustine, the Islamic philosopher Avicenna (Ibn Sina), Averroes (Ibn Rushd), and Jewish philosopher and theologian Maimonides. The Waldensians sect also incorporated rationalism into their movement.[33] One notable event in the Western timeline was the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas who attempted to merge Greek rationalism and Christian revelation in the thirteenth-century.[23][34] Generally, the Roman Catholic Church viewed Rationalists as a threat, labeling them as those who "while admitting revelation, reject from the word of God whatever, in their private judgment, is inconsistent with human reason."[35]

Classical rationalism

[edit]René Descartes (1596–1650)

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| René Descartes |

|---|

|

Descartes was the first of the modern rationalists and has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy.' Much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings,[36][37][38] which are studied closely to this day.

Descartes thought that only knowledge of eternal truths – including the truths of mathematics, and the epistemological and metaphysical foundations of the sciences – could be attained by reason alone; other knowledge, the knowledge of physics, required experience of the world, aided by the scientific method. He also argued that although dreams appear as real as sense experience, these dreams cannot provide persons with knowledge. Also, since conscious sense experience can be the cause of illusions, then sense experience itself can be doubtable. As a result, Descartes deduced that a rational pursuit of truth should doubt every belief about sensory reality. He elaborated these beliefs in such works as Discourse on the Method, Meditations on First Philosophy, and Principles of Philosophy. Descartes developed a method to attain truths according to which nothing that cannot be recognised by the intellect (or reason) can be classified as knowledge. These truths are gained "without any sensory experience", according to Descartes. Truths that are attained by reason are broken down into elements that intuition can grasp, which, through a purely deductive process, will result in clear truths about reality.

Descartes therefore argued, as a result of his method, that reason alone determined knowledge, and that this could be done independently of the senses. For instance, his famous dictum, cogito ergo sum or "I think, therefore I am", is a conclusion reached a priori i.e., prior to any kind of experience on the matter. The simple meaning is that doubting one's existence, in and of itself, proves that an "I" exists to do the thinking. In other words, doubting one's own doubting is absurd.[22] This was, for Descartes, an irrefutable principle upon which to ground all forms of other knowledge. Descartes posited a metaphysical dualism, distinguishing between the substances of the human body ("res extensa") and the mind or soul ("res cogitans"). This crucial distinction would be left unresolved and lead to what is known as the mind–body problem, since the two substances in the Cartesian system are independent of each other and irreducible.

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677)

[edit]The philosophy of Baruch Spinoza is a systematic, logical, rational philosophy developed in seventeenth-century Europe.[39][40][41] Spinoza's philosophy is a system of ideas constructed upon basic building blocks with an internal consistency with which he tried to answer life's major questions and in which he proposed that "God exists only philosophically."[41][42] He was heavily influenced by Descartes,[43] Euclid[42] and Thomas Hobbes,[43] as well as theologians in the Jewish philosophical tradition such as Maimonides.[43] But his work was in many respects a departure from the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition. Many of Spinoza's ideas continue to vex thinkers today and many of his principles, particularly regarding the emotions, have implications for modern approaches to psychology. To this day, many important thinkers have found Spinoza's "geometrical method"[41] difficult to comprehend: Goethe admitted that he found this concept confusing.[citation needed] His magnum opus, Ethics, contains unresolved obscurities and has a forbidding mathematical structure modeled on Euclid's geometry.[42] Spinoza's philosophy attracted believers such as Albert Einstein[44] and much intellectual attention.[45][46][47][48][49]

Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716)

[edit]Leibniz was the last major figure of seventeenth-century rationalism who contributed heavily to other fields such as metaphysics, epistemology, logic, mathematics, physics, jurisprudence, and the philosophy of religion; he is also considered to be one of the last "universal geniuses".[50] He did not develop his system, however, independently of these advances. Leibniz rejected Cartesian dualism and denied the existence of a material world. In Leibniz's view there are infinitely many simple substances, which he called "monads" (which he derived directly from Proclus).

Leibniz developed his theory of monads in response to both Descartes and Spinoza, because the rejection of their visions forced him to arrive at his own solution. Monads are the fundamental unit of reality, according to Leibniz, constituting both inanimate and animate objects. These units of reality represent the universe, though they are not subject to the laws of causality or space (which he called "well-founded phenomena"). Leibniz, therefore, introduced his principle of pre-established harmony to account for apparent causality in the world.

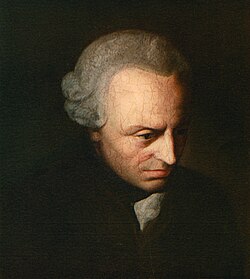

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Immanuel Kant |

|---|

|

|

Category • |

Kant is one of the central figures of modern philosophy, and set the terms by which all subsequent thinkers have had to grapple. He argued that human perception structures natural laws, and that reason is the source of morality. His thought continues to hold a major influence in contemporary thought, especially in fields such as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, and aesthetics.[51]

Kant named his brand of epistemology "Transcendental Idealism", and he first laid out these views in his famous work The Critique of Pure Reason. In it he argued that there were fundamental problems with both rationalist and empiricist dogma. To the rationalists he argued, broadly, that pure reason is flawed when it goes beyond its limits and claims to know those things that are necessarily beyond the realm of every possible experience: the existence of God, free will, and the immortality of the human soul. Kant referred to these objects as "The Thing in Itself" and goes on to argue that their status as objects beyond all possible experience by definition means we cannot know them. To the empiricist, he argued that while it is correct that experience is fundamentally necessary for human knowledge, reason is necessary for processing that experience into coherent thought. He therefore concludes that both reason and experience are necessary for human knowledge. In the same way, Kant also argued that it was wrong to regard thought as mere analysis. "In Kant's views, a priori concepts do exist, but if they are to lead to the amplification of knowledge, they must be brought into relation with empirical data".[52]

Contemporary rationalism

[edit]Rationalism has become a rarer label of philosophers today; rather many different kinds of specialised rationalisms are identified. For example, Robert Brandom has appropriated the terms "rationalist expressivism" and "rationalist pragmatism" as labels for aspects of his programme in Articulating Reasons, and identified "linguistic rationalism", the claim that the contents of propositions "are essentially what can serve as both premises and conclusions of inferences", as a key thesis of Wilfred Sellars.[53]

Outside of academic philosophy, some participants in the internet communities surrounding LessWrong and Slate Star Codex have described themselves as "rationalists" or the "rationalist community" in reference to rationality, rather than rationalism.[54][55][56] The term has also been used in this way by critics such as Timnit Gebru.[57]

Criticism

[edit]Rationalism was criticized by American psychologist William James for being out of touch with reality. James also criticized rationalism for representing the universe as a closed system, which contrasts with his view that the universe is an open system.[58]

Proponents of emotional choice theory criticize rationalism by drawing on new findings from emotion research in psychology and neuroscience. They point out that the rationalist paradigm is generally based on the assumption that decision-making is a conscious and reflective process based on thoughts and beliefs. It presumes that people decide on the basis of calculation and deliberation. However, cumulative research in neuroscience suggests that only a small part of the brain's activities operate at the level of conscious reflection. The vast majority of its activities consist of unconscious appraisals and emotions.[59] The significance of emotions in decision-making has generally been ignored by rationalism, according to these critics. Moreover, emotional choice theorists contend that the rationalist paradigm has difficulty incorporating emotions into its models, because it cannot account for the social nature of emotions. Even though emotions are felt by individuals, psychologists and sociologists have shown that emotions cannot be isolated from the social environment in which they arise. Emotions are inextricably intertwined with people's social norms and identities, which are typically outside the scope of standard rationalist accounts.[60] Emotional choice theory seeks to capture not only the social but also the physiological and dynamic character of emotions. It represents a unitary action model to organize, explain, and predict the ways in which emotions shape decision-making.[61]

See also

[edit]- 17th-century philosophy

- Critical rationalism

- Emotional choice theory

- Historical criticism

- Humanism

- Idealism

- Innatism

- Irrationalism

- Logical truth

- Natural philosophy

- Nominalism

- Noology

- Objectivism

- Objectivity (philosophy)

- Objectivity (science)

- Pancritical rationalism

- Panrationalism

- Phenomenology (philosophy)

- Philosophical realism

- Platonic realism

- Positivism

- Psychological nativism

- Rational choice theory

- Rational expectations

- Rational mysticism

- Rational realism

- Rationalist International

- Rationality and Power

- Realistic rationalism

- Pluralistic rationalism

- Scientific rationalism

- Theistic rationalism

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Rationalism". Britannica.com. 28 May 2023. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Audi, Robert (2015). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 902. ISBN 978-1107015050.

- ^ a b Bourke, Vernon J., "Rationalism", p. 263 in Runes (1962).

- ^ John Locke (1690), An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

- ^ a b Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "Rationalism vs. Empiricism" Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine First published August 19, 2004; substantive revision March 31, 2013 cited on May 20, 2013.

- ^ Audi, Robert, The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1995. 2nd edition, 1999, p. 771.

- ^ Oakeshott, Michael, "Rationalism in Politics", The Cambridge Journal 1947, vol. 1 Archived 2018-09-13 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ^ Boyd, Richard, "The Value of Civility?", Urban Studies Journal, May 2006, vol. 43 (no. 5–6), pp. 863–878 Archived 2012-04-01 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ^ FactCheck.org Mission Statement, January 2020 Archived 2019-11-02 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ Cottingham, John. 1984. Rationalism. Paladi/Granada.

- ^ Lacey, A.R. (1996), A Dictionary of Philosophy, 1st edition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1976. 2nd edition, 1986. 3rd edition, Routledge, London, 1996. p. 286

- ^ Sommers (2003), p. 15.

- ^ a b c Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Intuition/Deduction Thesis Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine First published August 19, 2004; substantive revision March 31, 2013 cited on May 20, 2013.

- ^ Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, 1704, New Essays on Human Understanding, Preface, pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Innate Knowledge Thesis Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine First published August 19, 2004; substantive revision March 31, 2013 cited on May 20, 2013.

- ^ Meno, 80d–e.

- ^ a b Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Innate Concept Thesis Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine First published August 19, 2004; substantive revision March 31, 2013 cited on May 20, 2013.

- ^ Cottingham, J., ed. (1996) [1986]. Meditations on First Philosophy With Selections from the Objections and Replies (revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521558181. – The original Meditations, translated, in its entirety.

- ^ René Descartes AT VII 37–38; CSM II 26.

- ^ Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, 1704, New Essays on Human Understanding, Preface, p. 153.

- ^ Locke, Concerning Human Understanding, Book I, Ch. III, Par. 20.

- ^ a b "rationalism | Definition, Types, History, Examples, & Descartes". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 May 2023. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "rationalism | Definition, Types, History, Examples, & Descartes | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 28 May 2023. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, 5.3.8–9 = Heraclides Ponticus fr. 88 Wehrli, Diogenes Laërtius 1.12, 8.8, Iamblichus VP 58. Burkert attempted to discredit this ancient tradition, but it has been defended by C.J. de Vogel, Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism (1966), pp. 97–102, and C. Riedweg, Pythagoras: His Life, Teaching, And Influence (2005), p. 92.

- ^ Modern English textbooks and translations prefer "Theory of Forms" to "Theory of Ideas", but the latter has a long and respected tradition starting with Cicero and continuing in German philosophy until present, and some English philosophers prefer this in English too. See W. D. Ross, Plato's Theory of Ideas (1951) and thisArchived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine reference site.

- ^ The name of this aspect of Plato's thought is not modern and has not been extracted from certain dialogues by modern scholars. The term was used at least as early as Diogenes Laërtius, who called it (Plato's) "Theory of Forms:" Πλάτων ἐν τῇ περὶ τῶν ἰδεῶν ὑπολήψει...., "Plato". Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Vol. Book III Paragraph 15.

- ^ Plato uses many different words for what is traditionally called form in English translations and idea in German and Latin translations (Cicero). These include idéa, morphē, eîdos, and parádeigma, but also génos, phýsis, and ousía. He also uses expressions such as to x auto, "the x itself" or kath' auto "in itself". See Christian Schäfer: Idee/Form/Gestalt/Wesen, in Platon-Lexikon, Darmstadt 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Forms (usually given a capital F) were properties or essences of things, treated as non-material abstract, but substantial, entities. They were eternal, changeless, supremely real, and independent of ordinary objects that had their being and properties by 'participating' in them. Plato's theory of forms (or ideas) Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Suzanne, Bernard F. "Plato FAQ: "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter"". plato-dialogues.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-19. Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- ^ Aristotle, Prior Analytics, 24b18–20.

- ^ [1] Archived 2018-08-28 at the Wayback Machine Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Ancient Logic Aristotle Non-Modal Syllogistic.

- ^ [2] Archived 2018-08-28 at the Wayback Machine Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Ancient Logic Aristotle Modal Logic.

- ^ Heckethorn, C.W. (2011). The Secret Societies of All Ages & Countries (Two Volumes in One). Cosimo Classics. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-61640-555-7. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-02-11.

- ^ Gill, John (2009). Andalucía : a cultural history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-0195376104.

- ^ Bellarmine, Robert (1902). . Sermons from the Latins. Benziger Brothers.

- ^ Bertrand Russell (2004) History of western philosophy Archived 2023-10-18 at the Wayback Machine pp. 511, 516–517

- ^ Heidegger [1938] (2002) p. 76 "Descartes... that which he himself founded... modern (and that means, at the same time, Western) metaphysics".

- ^ Watson, Richard A. (31 March 2012). "René Descartes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Lisa Montanarelli (book reviewer) (January 8, 2006). "Spinoza stymies 'God's attorney' – Stewart argues the secular world was at stake in Leibniz face off". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Kelley L. Ross (1999). "Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677)". History of Philosophy As I See It. Archived from the original on 2012-01-04. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

While for Spinoza all is God and all is Nature, the active/passive dualism enables us to restore, if we wish, something more like the traditional terms. Natura Naturans is the most God-like side of God, eternal, unchanging, and invisible, while Natura Naturata is the most Nature-like side of God, transient, changing, and visible.

- ^ a b c Anthony Gottlieb (July 18, 1999). "God Exists, Philosophically". The New York Times: Books. Archived from the original on 2023-10-18. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

Spinoza, a Dutch Jewish thinker of the 17th century, not only preached a philosophy of tolerance and benevolence but actually succeeded in living it. He was reviled in his own day and long afterward for his supposed atheism, yet even his enemies were forced to admit that he lived a saintly life.

- ^ a b c Anthony Gottlieb (2009-09-07). "God Exists, Philosophically (review of "Spinoza: A Life" by Steven Nadler)". The New York Times – Books. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ^ a b c Michael LeBuffe (book reviewer) (2006-11-05). "Spinoza's Ethics: An Introduction, by Steven Nadler". University of Notre Dame. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

Spinoza's Ethics is a recent addition to Cambridge's Introductions to Key Philosophical Texts, a series developed for the purpose of helping readers with no specific background knowledge to begin the study of important works of Western philosophy...

- ^ "Einstein Believes in 'Spinoza's God'; Scientist Defines His Faith in Reply, to Cablegram From Rabbi Here. Sees a Divine Order But Says Its Ruler Is Not Concerned 'Wit Fates and Actions of Human Beings'". The New York Times. April 25, 1929. Archived from the original on 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Hutchison, Percy (November 20, 1932). "Spinoza, "God-Intoxicated Man"; Three Books Which Mark the Three Hundredth Anniversary of the Philosopher's Birth 'Blessed Spinoza. A Biography'. By Lewis Browne. 319 pp. New York: Macmillan. 'Spinoza. Liberator of God and Man'. By Benjamin De Casseres, 145 pp. New York: E. Wickham Sweetland. 'Spinoza'. By Frederick Kettner. Introduction by Nicholas Roerich, New Era Library. 255 pp. New York: Roerich Museum Press. 'Spinoza'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2010-03-26. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ "Spinoza's First Biography Is Recovered; The Oldest Biography of Spinoza Edited with Translations, Introduction, Annotations, &c., by A. Wolf. 196 pp. New York: Lincoln Macveagh. The Dial Press". The New York Times. December 11, 1927. Archived from the original on 2010-03-26. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Irwin Edman (July 22, 1934). "The Unique and Powerful Vision of Baruch Spinoza; Professor Wolfson's Long-Awaited Book Is a Work of Illuminating Scholarship. (Book review) 'The Philosophy of Spinoza. By Henry Austryn Wolfson". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2010-03-26. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Cummings, M E (September 8, 1929). "Roth Evaluates Spinoza". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2010-03-24. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Social News Books (November 25, 1932). "Tribute to Spinoza Paid by Educators; Dr. Robinson Extols Character of Philosopher, 'True to the Eternal Light Within Him.' Hailed as 'Great Rebel'; De Casseres Stresses Individualism of Man Whose Tercentenary Is Celebrated at Meeting". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2010-03-26. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Archived 2020-08-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Immanuel Kant (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. 20 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-01-12. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ^ "Rationalism". abyss.uoregon.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27. Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- ^ Articulating reasons, 2000. Harvard University Press.

- ^ "Rationalist Movement – LessWrong". www.lesswrong.com. Archived from the original on 2023-06-17. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ Metz, Cade (2021-02-13). "Silicon Valley's Safe Space". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-04-20. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ The Rationalist's Guide to the Galaxy: Superintelligent AI and the Geeks Who Are Trying to Save Humanity's Future. Orion. 13 June 2019. ISBN 9781474608800. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "The Wide Angle: Understanding TESCREAL — Silicon Valley's Rightward Turn". May 2023. Archived from the original on 2023-06-06. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- ^ James, William (November 1906). The Present Dilemma in Philosophy (Speech). Lowell Institute.

- ^ See, for example, David D. Franks (2014), "Emotions and Neurosociology", in Jan E. Stets and Jonathan H. Turner, eds., Handbook of the Sociology of Emotions, vol. 2. New York: Springer, p. 267.

- ^ See Arlie Russell Hochschild (2012), The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, 3rd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ See Robin Markwica (2018), Emotional Choices: How the Logic of Affect Shapes Coercive Diplomacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sources

[edit]Primary

[edit]- Descartes, René (1637), Discourse on the Method.

- Spinoza, Baruch (1677), Ethics.

- Leibniz, Gottfried (1714), Monadology.

- Kant, Immanuel (1781/1787), Critique of Pure Reason.

Secondary

[edit]- Audi, Robert (ed., 1999), The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995. 2nd edition, 1999.

- Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0131585911.

- Blackburn, Simon (1996), The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1994. Paperback edition with new Chronology, 1996.

- Bourke, Vernon J. (1962), "Rationalism", p. 263 in Runes (1962).

- Douglas, Alexander X.: Spinoza and Dutch Cartesianism: Philosophy and Theology. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015)

- Fischer, Louis (1997). The Life of Mahatma Gandhi. HarperCollins. pp. 306–307. ISBN 0006388876.

- Förster, Eckart; Melamed, Yitzhak Y. (eds.): Spinoza and German Idealism. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012)

- Fraenkel, Carlos; Perinetti, Dario; Smith, Justin E. H. (eds.): The Rationalists: Between Tradition and Innovation. (Dordrecht: Springer, 2011)

- Hampshire, Stuart: Spinoza and Spinozism. (Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

- Huenemann, Charles; Gennaro, Rocco J. (eds.): New Essays on the Rationalists. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999)

- Lacey, A.R. (1996), A Dictionary of Philosophy, 1st edition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1976. 2nd edition, 1986. 3rd edition, Routledge, London, 1996.

- Loeb, Louis E.: From Descartes to Hume: Continental Metaphysics and the Development of Modern Philosophy. (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1981)

- Nyden-Bullock, Tammy: Spinoza's Radical Cartesian Mind. (Continuum, 2007)

- Pereboom, Derk (ed.): The Rationalists: Critical Essays on Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999)

- Phemister, Pauline: The Rationalists: Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz. (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2006)

- Runes, Dagobert D. (ed., 1962), Dictionary of Philosophy, Littlefield, Adams, and Company, Totowa, NJ.

- Strazzoni, Andrea: Dutch Cartesianism and the Birth of Philosophy of Science: A Reappraisal of the Function of Philosophy from Regius to 's Gravesande, 1640–1750. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018)

- Verbeek, Theo: Descartes and the Dutch: Early Reactions to Cartesian Philosophy, 1637–1650. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1992)

External links

[edit]- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Rationalism vs. Empiricism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Rationalism at PhilPapers

- Rationalism at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Homan, Matthew. "Continental Rationalism". In Fieser, James; Dowden, Bradley (eds.). Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. OCLC 37741658.

- Lennon, Thomas M.; Dea, Shannon. "Continental Rationalism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- John F. Hurst (1867), History of Rationalism Embracing a Survey of the Present State of Protestant Theology

Rationalism

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Distinctions

Epistemological Definition

In epistemology, rationalism is the position that reason serves as the primary source and test of knowledge, enabling the attainment of truths independent of sensory experience.[4] This approach prioritizes a priori knowledge—propositions known through intellectual intuition and deductive inference, such as mathematical equalities like 2 + 2 = 4 or logical necessities—which rationalists regard as more certain and universal than empirical generalizations.[5] Central to rationalism is the doctrine of innate ideas and concepts, positing that the human mind is endowed from birth with fundamental notions, including those of substance, causality, infinity, and God, which cannot be derived solely from observation but are elicited by rational reflection.[1] René Descartes, a foundational rationalist, articulated this in his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), where he employed methodical doubt to establish indubitable truths via "clear and distinct" perceptions accessible only to reason.[5] Similarly, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz argued in New Essays on Human Understanding (written 1704, published 1765) that predispositions to knowledge are innate, activated by minimal experience rather than created by it.[5] Rationalists contend that sensory data, prone to illusion and variability, must conform to the certainties yielded by reason, as exemplified in geometric proofs or self-evident axioms that hold necessarily across all possible worlds.[4] This emphasis on deduction from first principles underscores rationalism's commitment to knowledge as structured hierarchically, with foundational rational insights supporting derived conclusions, in contrast to accumulative empirical methods.[5]Contrast with Empiricism

Rationalism posits that certain knowledge is attainable through reason alone, independent of sensory experience, whereas empiricism asserts that all substantive knowledge originates from empirical observation and sensory data.[6] Rationalists, such as René Descartes (1596–1650), argued for the Intuition/Deduction Thesis, maintaining that clear and distinct perceptions grasped by the intellect provide infallible foundations, exemplified in mathematical truths like "2 + 3 = 5," which are known a priori without empirical verification.[6] In contrast, empiricists like John Locke (1632–1704) rejected innate ideas, proposing the mind as a tabula rasa (blank slate) at birth, where simple ideas arise solely from sensation or reflection on sensations, building complex knowledge through association and induction.[7] The core epistemological divergence lies in the treatment of a priori knowledge: rationalists claim it extends to synthetic propositions beyond tautologies, such as causal necessities or substantive universals, derived deductively from innate concepts like substance or infinity, as defended by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) in his critique of Locke's empiricism.[6] Empiricists, including David Hume (1711–1776), countered that a priori cognitions are limited to analytic relations of ideas (e.g., definitions), with synthetic knowledge—such as expectations of causation—arising from habitual conjunctions observed in experience, vulnerable to skepticism about unobserved instances.[7] This debate underscores rationalism's emphasis on deductive certainty for universal truths, versus empiricism's inductive probability grounded in repeatable observations, with rationalists viewing pure reason as transcending fallible senses to access metaphysical realities.[8] While both camps acknowledge reason's role in processing data—rationalists in deducing from intuitions, empiricists in analyzing experiences—their methodological priorities differ sharply: rationalism prioritizes apodictic demonstration akin to geometry for philosophy, as Descartes outlined in his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), whereas empiricism favors experimental verification, as championed by Locke in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), influencing the scientific revolution's empirical turn.[6] Rationalists critiqued empiricism for conflating psychological origins with justificatory grounds, arguing that denying innateness leads to infinite regress in justifying basic concepts; empiricists retorted that rationalist appeals to intuition risk dogmatism, unsubstantiated without experiential anchors.[9] This tension persists in modern epistemology, though hybrid views like Kantian synthesis later attempted reconciliation by positing a priori structures conditioning experience.[5]Non-Philosophical Usages

In politics, rationalism denotes an approach to governance and policy-making that prioritizes abstract reasoning and technical knowledge derived from first principles over practical experience, tradition, or tacit wisdom. Michael Oakeshott, in his 1962 essay "Rationalism in Politics," characterized this as a disposition among reformers who seek to remake society through comprehensive, logically deduced blueprints, dismissing incremental customs as irrational relics; he argued such rationalism overlooks the inevitably incomplete nature of human knowledge and leads to coercive utopian schemes.[10] This critique has influenced conservative thought, highlighting how rationalist politics underestimates the role of unarticulated habits in sustaining social order.[11] In economics, particularly in Australian discourse since the 1980s, economic rationalism describes a policy framework rooted in neoclassical principles, advocating deregulation, privatization of state assets, free-market competition, and reduced government intervention to maximize efficiency and resource allocation. Proponents, often associated with neoliberal reforms under leaders like Bob Hawke and Paul Keating, viewed these measures as logically compelled by market dynamics, yielding outcomes such as the floating of the Australian dollar in 1983 and tariff reductions that boosted GDP growth to an average of 3.5% annually through the 1990s.[12] Critics, however, contend it prioritizes fiscal metrics over social equity, contributing to income inequality rises from a Gini coefficient of 0.27 in 1980 to 0.33 by 2000.[13] In religious contexts, rationalism refers to movements or views that subordinate scriptural authority or dogma to human reason as the ultimate arbiter of truth, often interpreting divine revelation as accessible through logical demonstration rather than blind faith. This usage emerged prominently during the Enlightenment, where figures like Herbert of Cherbury (1583–1648) proposed innate rational principles of religion, such as belief in a supreme deity and moral accountability, independent of specific revelations.[14] Theistic rationalism, a variant, affirms an active divine role while insisting on reason's primacy, as seen in some Founding Fathers' deistic leanings that blended natural theology with empirical observation, rejecting miracles as incompatible with uniform natural laws.[15] Such approaches have fueled freethought organizations, like the Rationalist Society of Australia founded in 1919, which promote evidence-based ethics over supernatural claims.[16] In international relations theory, rationalism constitutes a methodological paradigm emphasizing actors' self-interested calculations under anarchy, akin to rational choice models, to explain state behavior without relying solely on material power or ideational constructs. Developed in the 1990s as a via media between realism and liberalism, it posits that cooperation emerges from iterated games where states rationally pursue absolute gains, as formalized in regime theory with equilibria like tit-for-tat strategies yielding stable outcomes in iterated prisoner's dilemmas.[17] This framework underpins analyses of institutions like the World Trade Organization, where rational bargaining reduced global tariffs from 40% post-WWII to under 5% by 2020.[18]Core Theses

Intuition and Deduction Thesis

The intuition and deduction thesis asserts that some propositions are knowable a priori through direct intellectual apprehension (intuition) or logical inference therefrom (deduction), providing substantive knowledge beyond mere analytic truths or empirical data.[19] This approach contrasts with empiricism by positing reason as a reliable source for facts about reality, such as mathematical necessities or metaphysical principles.[20] René Descartes, in his Rules for the Direction of the Mind (c. 1628), defines intuition as "the conception of a clear and attentive mind so direct and distinct that of itself it leaves no room for the possibility of doubt," exemplified by immediately grasping that 2 + 3 = 5 or that a triangle's angles sum to 180 degrees without sensory reliance.[21] Deduction, he explains, consists of "all those inferences whose conclusions we derive by following the correct order, provided we have complete grasp of everything that precedes them," ensuring certainty through an unbroken chain of intuitions, as in Euclidean geometry where theorems follow deductively from axioms.[21] Descartes argues these methods yield indubitable knowledge because they depend solely on the mind's clarity, immune to sensory deception.[21] In application, Descartes employs intuition and deduction in Meditations on First Philosophy (1641) to establish foundational truths: the cogito ("I think, therefore I am") is intuited as self-evident, while proofs for God's existence and the reliability of clear perceptions are deduced via ontological and causal arguments. This thesis extends to rationalists like Baruch Spinoza, whose Ethics (1677) demonstrates propositions deductively from intuitive definitions and axioms in geometric style, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who uses logical deduction from innate principles to derive truths about substance and monads. Critics, including empiricists like David Hume, contend that such reasoning merely reveals conceptual relations, not empirical facts, as deductions presuppose unverified premises. However, rationalists maintain that intuition's self-evidence and deduction's validity secure knowledge of contingent matters when combined with proofs of a non-deceptive divine intellect.[19]Innate Knowledge Thesis

The Innate Knowledge Thesis maintains that certain propositional knowledge is inherent to human nature, acquired independently of sensory experience and present from birth as part of our rational faculties.[6] This a priori knowledge encompasses necessary truths, such as logical principles or self-evident axioms, which are not derived from empirical observation but form the basis for further reasoning.[6] Unlike knowledge gained through intuition or deduction alone, innate knowledge is posited as preexisting in the mind, potentially latent until activated by reflection or minimal external prompts, ensuring universality across individuals despite variations in upbringing.[6] René Descartes articulated this thesis in his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), arguing that foundational propositions like the cogito ("I think, therefore I am") and the existence of God as an infinite, perfect being constitute innate knowledge directly implanted by God in the human intellect.[6] He contended that such knowledge cannot stem from sensory data, which is finite and prone to error, nor from the mind's autonomous fabrication, as the idea of infinite perfection exceeds human compositional capacity; instead, it must originate from a divine source, evident through clear and distinct perception.[22] Descartes classified ideas supporting this knowledge as innate, alongside those of the self and body, distinguishing them from adventitious (sensory-derived) or factitious (invented) ones.[22] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz advanced the thesis in New Essays Concerning Human Understanding (written 1704, published 1765), asserting that principles of contradiction ("A cannot both be and not be") and sufficient reason ("nothing occurs without a reason") are innate, as sensory experience provides only contingent instances incapable of yielding universal necessities.[6] Leibniz rejected John Locke's tabula rasa empiricism, proposing instead that innate knowledge resembles predispositions in nature, such as veins in marble guiding the sculptor's chisel toward certain forms; experience occasions awareness, but the truths themselves are predisposed by rational structure.[23] He extended this to mathematical and moral axioms, arguing their cross-cultural recognition and necessity imply an original endowment rather than learned accumulation.[24] The thesis traces earlier roots to Plato's Meno (c. 380 BCE), where knowledge of geometry is depicted as recollected from the soul's prenatal state, suggesting innateness through anamnesis rather than empirical learning.[6] Rationalists invoked it to explain why infants or uneducated individuals intuitively grasp self-evident truths, countering empiricist claims of blank-slate learning by emphasizing causal origins in intellectual endowment over environmental input.[6] While challenged by empiricists for lacking universal conscious assent—e.g., Locke's observation that principles are not uniformly recognized in children or diverse societies—the thesis underscores rationalism's commitment to reason's autonomy in accessing non-contingent realities.[6]Innate Concepts Thesis

The Innate Concepts Thesis asserts that certain fundamental concepts, such as those of substance, causality, infinity, and God, are inherent to the human mind's rational structure and not acquired through sensory experience or abstraction from particulars.[6] This view distinguishes rationalism from empiricism by emphasizing the mind's pre-equipped capacity to form universal and necessary ideas independently of empirical input.[25] René Descartes, in his Meditations on First Philosophy published in 1641, identified innate ideas including the concept of a perfect being (God), the thinking self (cogito), and mathematical essences like the equality of a triangle's interior angles to two right angles.[25] He argued these cannot derive from the senses, which provide only confused and finite representations, nor from the intellect's fabrication, as their clarity and distinctness exceed human invention; instead, they must be divinely implanted at birth to guarantee certain knowledge.[6] Descartes classified ideas as innate, adventitious (from senses), or factitious (invented), with innate ones serving as the foundation for deductive reasoning about reality.[25] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz extended the thesis in his New Essays Concerning Human Understanding (written 1704, published 1765), proposing that all concepts arise from innate principles or "dispositions" in the soul, comparable to veins predisposing a marble block toward a particular statue form rather than requiring external carving from experience alone.[25] Leibniz maintained that even seemingly empirical concepts involve innate logical structures, such as the principle of sufficient reason, enabling the mind to discern necessities like the law of non-contradiction without deriving them solely from observation.[23] He reconciled apparent experiential learning by distinguishing virtual from actual innateness, where concepts are unconsciously present until triggered by sensation.[6] Proponents supported the thesis through observations of conceptual universality—e.g., all peoples grasp causality despite diverse experiences—and the presence of abstract ideas in infants or the uneducated, which exceed sensory composition.[23] Leibniz cited linguistic evidence, noting that children acquire complex grammar not explicitly taught, implying innate cognitive faculties.[23] These arguments prioritize a priori reasoning over inductive generalization, positing that denying innate concepts undermines the reliability of mathematics and metaphysics, fields reliant on non-empirical necessities.[25]Historical Development

Ancient Origins

The roots of rationalism emerged in ancient Greece during the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, as philosophers shifted from mythological accounts to explanations grounded in reason and abstract principles. This transition prioritized logical deduction and mathematical insight over empirical observation, laying foundational ideas for later rationalist epistemologies that emphasize innate structures of thought.[26] Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570–495 BCE) initiated this rationalist orientation by positing that the cosmos is fundamentally mathematical, with numbers embodying the essence of reality and governing natural harmonies. His followers discovered the Pythagorean theorem, relating the sides of right triangles via the equation , and conceived the harmony of the spheres, where planetary motions align with numerical ratios inaudible to senses but discernible through calculation. Such views asserted that true knowledge derives from rational apprehension of eternal numerical relations, not sensory flux.[27][28] Pre-Socratic thinkers like Parmenides of Elea (c. 515–450 BCE) advanced rationalism by using pure logic to argue that reality is a single, unchanging, and indivisible Being, rejecting sensory evidence of change and multiplicity as deceptive. In his poem On Nature, Parmenides employed deductive reasoning to claim that "what is" must be whole and eternal, as non-being cannot exist or be thought, establishing reason as the arbiter of truth superior to perception. Plato (c. 427–347 BCE) systematized these ideas in his theory of Forms and recollection, contending that genuine knowledge involves recollecting eternal, immaterial ideals known to the immortal soul before birth. In the Meno, Socrates guides an unlettered slave boy to solve a geometric problem via questions alone, demonstrating innate cognitive capacities elicited by dialectic rather than instruction from experience. Similarly, the Phaedo posits learning as anamnesis, recovery of prenatal acquaintance with Forms like Equality itself, accessed through reason while senses provide mere opinion.[29][30] Aristotle (384–322 BCE), Plato's student, critiqued separate Forms as unnecessary, favoring empirical collection of data to induce universals, yet retained rationalist elements in his logic and metaphysics. His syllogistic deduction presumed innate principles like non-contradiction, and the active intellect abstracts essences beyond particulars, though he subordinated reason's a priori role to sensory foundations, marking a partial empiricist turn.[31][6]Pythagoras and Pre-Socratics

The Pre-Socratic philosophers of the 6th and 5th centuries BCE marked an early turn toward rational inquiry by seeking natural explanations for cosmic order through reason rather than mythological traditions.[32] Figures such as Thales, Anaximander, and Heraclitus employed speculative reasoning to identify underlying principles like water, the boundless, or flux as the primary substances or processes governing reality, prioritizing logical coherence over empirical verification or divine intervention.[32] This foundational emphasis on logos—reasoned discourse—established a precedent for deriving knowledge from abstract principles, influencing later rationalist traditions despite the speculative nature of their cosmologies.[32] Pythagoras (c. 570–c. 490 BCE), operating within this milieu, advanced a numerical ontology wherein numbers constituted the true essence of all things, accessible primarily through mathematical insight rather than sensory data.[33] His school discovered proportional relationships, such as the 2:1 ratio producing an octave in musical harmony, illustrating how deductive reasoning from ideal forms could reveal structural harmonies in the observable world.[33] The Pythagorean theorem itself exemplifies this rationalist strand, derived as a universal geometric truth via abstract proof independent of particular instances, underscoring mathematics as a pathway to certain knowledge.[33] Though intertwined with mystical elements like soul transmigration, Pythagoreanism's privileging of quantifiable, eternal principles over transient appearances prefigured rationalism's core commitment to reason's primacy in epistemology.[33]Plato

Plato (c. 427–347 BCE), an Athenian philosopher and student of Socrates, laid foundational elements of rationalism by positing that true knowledge derives from reason and intellectual intuition rather than sensory perception.[34] In his theory of Forms, eternal and immutable ideal entities exist independently of the physical world, accessible only through dialectical reasoning and philosophical contemplation.[35] Sensory experiences, Plato contended, provide mere opinions (doxa) about imperfect shadows or imitations of these Forms, which distort reality and cannot yield certain knowledge.[36] Central to Plato's epistemology is the doctrine of recollection (anamnesis), articulated in dialogues such as the Meno and Phaedo. In the Meno, Socrates guides an uneducated slave boy through geometric questions, eliciting correct solutions without prior instruction, suggesting the soul possesses innate knowledge acquired before birth during contemplation of the Forms.[37] This resolves Meno's paradox of inquiry—how one can seek knowledge one lacks—by framing learning as remembrance rather than empirical acquisition.[38] Plato extended this to innate concepts like justice and beauty, arguing the immortal soul's pre-existence enables a priori grasp of universals, independent of experience.[19] In the Republic, Plato's divided line analogy further delineates rationalist epistemology, distinguishing visible (sensible) from intelligible realms, with highest knowledge (noesis) attained via pure reason's ascent to the Form of the Good.[39] This method prioritizes deduction from first principles over induction from particulars, influencing later rationalists despite Aristotle's critiques emphasizing empirical observation. Plato's Academy, founded c. 387 BCE, institutionalized these ideas, training philosophers in abstract reasoning over empirical sciences.[34]Aristotle

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), a student of Plato, advanced the rationalist tradition through his development of formal logic and theory of scientific demonstration, emphasizing deduction from first principles as the path to certain knowledge. In works such as the Prior Analytics and Posterior Analytics, he formalized syllogistic reasoning, a deductive method where conclusions follow necessarily from premises, providing a rigorous framework for deriving truths from axioms that later rationalists like Descartes would adapt.[31][40] This approach positioned knowledge as hierarchical: universals grasped intuitively by the nous (intellect) serve as starting points for demonstrations, contrasting with mere opinion derived from perception alone.[41] Unlike Plato's reliance on innate recollection of eternal Forms, Aristotle integrated empirical induction to abstract first principles from sensory data, arguing that repeated observations yield experience (empeiria), which the intellect then universalizes into self-evident truths like the principle of non-contradiction.[41] He contended that true episteme (scientific knowledge) requires demonstrating effects from causes via deduction, ensuring necessity and universality, as outlined in Posterior Analytics I.2–7.[31] This blend of induction for principles and deduction for theorems influenced medieval scholastics and early modern rationalists, who prioritized reason's deductive power over unchecked empiricism.[42] Aristotle's epistemology thus exhibits rationalist elements in its privileging of intellect over senses for ultimate justification, though he rejected pure a priori knowledge without experiential grounding, avoiding the infinite regress of proofs by positing nous as the faculty apprehending indemonstrable principles directly.[43] Critics of rationalist interpretations note that his method remains empirically anchored, with first principles emerging from perceptual habits rather than innate ideas, marking a departure from strict rationalism toward a hybrid realism.[44] Nonetheless, his logical innovations, including the square of opposition and categorical propositions, supplied indispensable tools for rationalist argumentation, enduring until supplanted by modern symbolic logic in the 19th century.[31]Medieval Rationalism

Medieval rationalism emerged within the scholastic tradition of the Latin West, where philosophers systematically applied Aristotelian logic and dialectical reasoning to theological questions, aiming to demonstrate the compatibility of faith and reason while subordinating the latter to divine revelation. Unlike modern rationalism's emphasis on autonomous reason and innate ideas derived from doubt, medieval thinkers viewed reason as a tool for illuminating revealed truths, often starting from the premise of faith's primacy. This approach gained momentum in the 11th century amid renewed access to ancient texts, particularly Aristotle's works translated into Latin around 1120–1250, which provided rigorous methods for argumentation.[45] Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033–1109), often regarded as the father of scholasticism, exemplified early rationalist theology with his principle of fides quaerens intellectum ("faith seeking understanding"), articulated in works like the Monologion (1076) and Proslogion (1077–1078). In the Proslogion's ontological argument, Anselm posited that God, defined as "a being than which none greater can be conceived," must exist in reality, as existence in reality is greater than mere conceptual existence; thus, denying God's existence leads to a contradiction. This a priori deduction relied solely on the coherence of the divine concept, independent of empirical evidence, marking a rationalist commitment to reason's power in metaphysics, though framed within a theistic context.[46] Peter Abelard (1079–1142) advanced scholastic rationalism through dialectical method, compiling apparent contradictions from authoritative texts in Sic et Non (c. 1121–1122) and resolving them via logical analysis, emphasizing intent and conceptual distinctions over blind adherence to tradition. Abelard's approach treated theology as a science amenable to rational scrutiny, arguing that truths could be discerned by weighing reasons pro and contra, which influenced later scholastics but drew criticism for potentially undermining scriptural authority. His nominalist leanings on universals further highlighted reason's role in clarifying language and concepts, prefiguring debates on innate versus acquired knowledge.[47][48] Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) synthesized these elements in his Summa Theologica (1265–1274), integrating Aristotelian empiricism with rational proofs for God's existence via the quinque viae (five ways), which derive from observable effects like motion, causation, and contingency to infer a necessary first cause. Aquinas maintained that reason can establish preambles of faith, such as God's existence and basic attributes, but cannot fully comprehend supernatural mysteries like the Trinity, which require revelation; thus, faith perfects reason without contradicting it. This harmony distinguished scholastic rationalism from fideism, though Aquinas critiqued excessive rationalism by affirming reason's limits against pure intellectualism.[49][50] In late medieval developments, figures like John Duns Scotus (c. 1266–1308) extended rationalist metaphysics with arguments for God's existence based on the univocity of being and innate conceptual necessities, while William of Ockham (c. 1287–1347) curtailed speculative reason via his razor principle, prioritizing simplicity and empirical verification over elaborate a priori constructs. These tensions foreshadowed the decline of high scholastic rationalism amid nominalist skepticism and the Renaissance shift toward humanism, yet the medieval legacy endured in its methodical use of logic to defend orthodoxy against heresies and secular doubts.[51]Early Modern Rationalism

Early Modern Rationalism, often termed Continental Rationalism, emerged in the 17th and early 18th centuries as a philosophical approach privileging reason and innate intellectual capacities over sensory experience as the primary sources of certain knowledge.[52] This movement developed amid the scientific revolution's challenges to traditional Aristotelianism and skepticism induced by new astronomical and mechanical discoveries, prompting philosophers to seek indubitable foundations for knowledge through a priori deduction and intuition.[52] Key figures included René Descartes (1596–1650), Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), who, despite divergences, shared commitments to innate ideas—such as concepts of God, substance, and mathematical truths—and the method of deriving truths via logical inference from self-evident principles.[25] Central to this rationalism was the rejection of empiricist reliance on observation, asserting instead that genuine understanding arises from the mind's inherent structures, enabling knowledge independent of potentially deceptive senses.[6] Descartes initiated this shift in works like Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), employing systematic doubt to establish the cogito as an indubitable starting point, from which clear and distinct ideas could be deductively expanded.[25] Spinoza advanced a geometric method in Ethics (1677), presenting a monistic metaphysics where knowledge progresses from adequate ideas innate to the intellect.[52] Leibniz, in Monadology (1714), posited infinite simple substances (monads) governed by the principle of sufficient reason, with all truths analytically unfolding from innate notions.[25] Metaphysically, these thinkers emphasized substance as a unifying reality, connecting attributes and enabling persistence over time, though they differed—Descartes on dual substances (mind and body), Spinoza on one infinite substance, and Leibniz on a plurality of monads.[52] No unified manifesto bound them, yet their collective insistence on reason's autonomy contrasted sharply with British empiricists like Locke and Hume, influencing subsequent debates on epistemology and laying groundwork for Kant's critical philosophy.[25] This rationalist framework prioritized certainty in logic, mathematics, and metaphysics, viewing denial of fundamental principles as self-contradictory.[6]René Descartes