Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

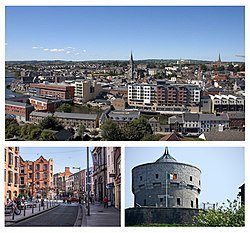

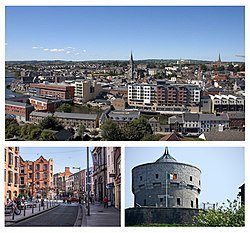

Drogheda

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Drogheda (/ˈdrɒhədə, ˈdrɔːdə/ DRO-həd-ə, DRAW-də; Irish: Droichead Átha [ˈd̪ˠɾˠɛhəd̪ˠ ˈaːhə] ⓘ, meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, 43 km (27 mi) north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth but with the south fringes of the town in County Meath, 40 km (25 mi) north of Dublin city centre. Drogheda had a population of 44,135 inhabitants in 2022, making it the eleventh largest settlement by population in all of Ireland, and the largest town in the Republic of Ireland,[a] by both population and area.[4] It is the second largest in County Louth with 35,990 and sixth largest in County Meath with 8,145. It is the last bridging point on the River Boyne before it enters the Irish Sea. The UNESCO World Heritage Site of Newgrange is located 8 km (5.0 mi) west of the town.

Area

[edit]

Drogheda was founded as two separately administered towns in two different territories: Drogheda-in-Meath (i.e. the Lordship and Liberty of Meath, from which a charter was granted in 1194) and Drogheda-in-Oriel (or 'Uriel', as County Louth was then known). The division came from the twelfth-century boundary between two Irish kingdoms, colonised by different Norman interests, just as the River Boyne continues to divide the town between the dioceses of Armagh and Meath. In 1412, these two towns were united, and Drogheda became a county corporate, styled as "the County of the Town of Drogheda". Drogheda continued as a county borough until the establishment of county councils under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, which saw all of Drogheda, including a large area south of the Boyne, become part of an extended County Louth. With the passing of the County of Louth and Borough of Drogheda (Boundaries) Provisional Order 1976, County Louth again grew larger at the expense of County Meath. The boundary was further altered in 1994 by the Local Government (Boundaries) (Town Elections) Regulations 1994. The 2007–2013 Meath County Development Plan recognises the Meath environs of Drogheda as a primary growth centre on a par with Navan.

History

[edit]

Hinterland

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1811 | 15,590 | — |

| 1813 | 16,123 | +3.4% |

| 1821 | 18,118 | +12.4% |

| 1831 | 17,365 | −4.2% |

| 1841 | 17,300 | −0.4% |

| 1851 | 16,810 | −2.8% |

| 1861 | 14,722 | −12.4% |

| 1871 | 13,510 | −8.2% |

| 1881 | 12,297 | −9.0% |

| 1891 | 11,873 | −3.4% |

| 1901 | 12,760 | +7.5% |

| 1911 | 12,501 | −2.0% |

| 1926 | 12,716 | +1.7% |

| 1936 | 14,494 | +14.0% |

| 1946 | 15,715 | +8.4% |

| 1951 | 16,779 | +6.8% |

| 1956 | 17,008 | +1.4% |

| 1961 | 17,085 | +0.5% |

| 1966 | 17,908 | +4.8% |

| 1971 | 20,095 | +12.2% |

| 1981 | 23,615 | +17.5% |

| 1986 | 24,681 | +4.5% |

| 1991 | 24,656 | −0.1% |

| 1996 | 25,282 | +2.5% |

| 2002 | 31,020 | +22.7% |

| 2006 | 35,090 | +13.1% |

| 2011 | 38,578 | +9.9% |

| 2016 | 40,956 | +6.2% |

| 2022 | 44,135 | +7.8% |

| [5][6][4] | ||

The town is situated in an area which contains a number of archaeological monuments dating from the Neolithic period onwards, of which the large passage tombs of Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth are probably the best known.[7] The density of archaeological sites of the prehistoric and early Christian periods uncovered in the course of ongoing developments, (including during construction of the Northern Motorway or 'Drogheda Bypass'), has shown that the hinterland of Drogheda has been a settled landscape for millennia.[8][9]

Town beginnings

[edit]

Despite local tradition linking Millmount to Amergin Glúingel, in his 1978 study of the history and archaeology of the town, John Bradley stated that "neither the documentary nor the archaeological evidence indicates that there was any settlement at the town prior to the coming of the Normans".[10] The results of a number of often large-scale excavations carried out within the area of the medieval town appear to confirm this statement.[11]

One of the earliest structures in the town is the motte-and-bailey castle, now known as Millmount Fort, which overlooks the town from a bluff on the south bank of the Boyne and which was probably erected by the Norman Lord of Meath, Hugh de Lacy, sometime before 1186. The wall on the east side of Rosemary Lane, a back-lane which runs from St. Laurence Street towards the Augustinian Church, is the oldest stone structure in Drogheda.[12] It was completed in 1234 as the west wall of the first castle guarding access to the northern crossing point of the Boyne. A later castle, circa 1600, called Laundy's Castle stood at the junction of West Street and Peter's Street. On Meathside, the Castle of Drogheda or The Castle of Comfort was a tower house castle on the south side of the Bull Ring. It served as a prison, and as a sitting of the Irish parliament in 1494.[13] The earliest known town charter is that granted to Drogheda-in-Meath by Walter de Lacy in 1194.[14] In the 1600s, the name of the town was also spelled "Tredagh" in keeping with the common pronunciation, as documented by Gerard Boate in his work Irelands' Natural History. In c. 1655 it was spelled "Droghedagh" on a map by William Farriland.[15]

Drogheda was an important walled town in the English Pale in the medieval period. It frequently hosted meetings of the Irish Parliament at that time. According to R.J. Mitchell in John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester, in a spill-over from the War of the Roses the Earl of Desmond and his two youngest sons (still children) were executed there on Valentine's Day 1468 on orders of the Earl of Worcester, the Lord Deputy of Ireland. It later came to light (for example in Robert Fabyan's The New Chronicles of England and France), that Elizabeth Woodville, the queen consort, was implicated in the orders given.[16] The parliament was moved to the town in 1494 and passed Poynings' Law, the most significant legislation in Irish history, a year later. This effectively subordinated the Irish Parliament's legislative powers to the King and his English Council.

Later events

[edit]

The town was besieged twice during the Irish Confederate Wars.

In the second siege of Drogheda, an assault was made on the town from the south, the tall walls breached, and the town was taken by Oliver Cromwell on 11 September 1649,[17] as part of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and it was the site of a massacre of the Royalist defenders. In Cromwell's own words after the siege of Drogheda, "When they submitted, their officers were knocked on the head, and every tenth man of the soldiers killed and the rest shipped to Barbados."[18]

In 1661, Henry Moore, 3rd Viscount Moore was created the Earl of Drogheda in the Peerage of Ireland.

The Battle of the Boyne, 1690, occurred some 6 km (3.7 mi) west of the town, on the banks of the River Boyne, at Oldbridge. The Tholsel in West Street was completed in 1770.[19]

In 1790, Drogheda Harbour Commissioners were established by the Port of Drogheda Act 1790.[20] They remained in place until 1997 when a commercial enterprise, the Drogheda Port Company, replaced them.

In 1825, the Drogheda Steam Packet Company was formed in the town, providing shipping services to Liverpool.

In 1837, the population of Drogheda area was 17,365 people, of whom 15,138 lived in the town.[21]

Town arms

[edit]Drogheda's coat of arms features St. Laurence's Gate with three lions, and a ship emerging from either side of the barbican. It is blazoned as Azure per pale dimidiated, on the dexter side three lions passant guardant in pale or, on the sinister as many hulls of ships in pale of the last, surmounted by a castle with two towers triple-towered argent.[22] The town's motto Deus praesidium, mercatura decus translates as "God our strength, merchandise our glory".

The star and crescent emblem in the crest of the coat of arms is mentioned as part of the mayor's seal by D'Alton (1844).[23] In 2010, Irish president Mary McAleese, in a speech delivered during an official visit to Turkey, stated that the star and crescent had been added in the aftermath of the Great Famine as gratitude for food supplies donated by the Ottoman Sultan Abdülmecid I, which had arrived at Drogheda by ship. Irish press quickly pointed out the story was a myth, with a local historian calling it 'nothing short of sheer nonsense,' and the star and crescent dating back to King John.[24][25] Later evidence, including a letter displayed at the office of the European Commission, showed that the Sultan did send aid during the 1845–1852 famine.[26][27]

20th century

[edit]

In 1921, the preserved severed head of Saint Oliver Plunkett, who was executed in London in 1681, was put on display in St. Peter's (Catholic) Church, where it remains today. The church is located on West Street, which is the main street in the town.

In 1979, Pope John Paul II visited Drogheda as part of his five-stop tour of Ireland. He arrived less than a month after the IRA assassination of Lord Mountbatten, Queen Elizabeth's cousin, in Mullaghmore. On 29 September 1979, he arrived in Dublin, where he gave his first mass. He then addressed 300,000 people in Drogheda, where he appealed "on his knees" to paramilitaries to end the violence in Ireland:[28][29][30]

"Now I wish to speak to all men and women engaged in violence. I appeal to you, in language of passionate pleading. On my knees I beg you to turn away from the paths of violence and to return to the ways of peace. You may claim to seek justice. I too believe in justice and seek justice. But violence only delays the day of justice. Violence destroys the work of justice. Further violence in Ireland will only drag down to ruin the land you claim to love and the values you claim to cherish."[31]

21st century

[edit]Two decades into the 21st century some of the historic core of Drogheda town has suffered urban decline. Some of the buildings have been derelict for some years and are in danger of collapse.[32] There was a 2006 traffic plan for pedestrianisation of West Street. It was rejected at a vote of the elected councillors. They had come under pressure from traders in the area concerned about a potential further decline in customer footfall. But the issue has come up for debate again.[33] When asked, Drogheda residents point out that a combination of expensive car-parking and high commercial rates had a push-pull effect on the town's centre. Shops were forced to close and at the same time shoppers brought their business to retail parks such as the Boyne Shopping Centre on Bolton Street.[34] A substantial root-and-branch approach to renewal of the locality was proposed in "Westgate Vision: A Townscape Recovery Guide". The Westgate area of Drogheda is to be subject to a 10-year regeneration by Louth County Council.[35]

Demographics

[edit]Drogheda has a hinterland of 70,000+ within a 15 km (9.3 mi) radius. According to the 2022 census, there were 44,135 people living in Drogheda town at that time.[4]

As of the 2011 census, non-Irish nationals accounted for 16.1% of the population, compared with a national average of 12%. Polish nationals (1,127) were the largest group, followed by Lithuanian nationals (1,044 people).[36] As of the 2016 census, 17.4% of the population were non-Irish nationals, with 676 people from the UK, 1,324 Polish nationals, 1,014 Lithuanians, 1,798 people from elsewhere in the EU, and 1,400 with other (non-EU) nationalities.[37]

As of the 2022 census,[38] the ethnic makeup of the town was 80.65% white total, including 67.81% white Irish and 12.57% other white people, 7.48% not stated, 5.7% Asian, 2.44% other and 3.73% black.

Arts and entertainment

[edit]Music

[edit]The town was selected to host Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann for two years in 2018 and 2019.[39]

Drogheda is home to two brass bands: Drogheda Brass Band and Lourdes Brass Band. In 2014, the town hosted the international summer Samba festival in which samba bands from around the world came to the town for three days of drumming and parades.[40]

The composer and member of Aosdána, Michael Holohan, has lived in Drogheda since 1983. His compositions have been performed and broadcast both at home and internationally. Career highlights in Drogheda include Cromwell 1994, 'Drogheda 800' (RTECO, Lourdes Church); The Mass of Fire 1995, 'Augustinian 700' (RTÉ TV live broadcast); No Sanctuary 1997 with Nobel Laureate and poet Seamus Heaney (Augustinian Church); Remembrance Sunday Service and Drogheda Unification 600 (RTE TV live broadcast, St Peter's Church of Ireland) and two major concerts with The Boyne Valley Chamber Orchestra at Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann in 2018 and 2019.

Drogheda regularly hosts "Music at the Gate", a community-run event led by uilleann piper Darragh Ó Heiligh, next to Saint Laurence's Gate in the centre of Drogheda.[41]

Drogheda Arts Festival, a mix of music, live performance and street entertainment, is held over the May Bank Holiday weekend.[citation needed]

Visual arts

[edit]October 2006 saw the opening of the Highlanes Gallery, the town's first dedicated municipal art gallery. It is located in the former Franciscan Church and Friary on St. Laurence Street. The gallery houses Drogheda's municipal art collection, which dates from the 17th century.

Places of interest

[edit]

Drogheda is an ancient town that has a growing tourism industry.[42] It has a UNESCO World Heritage site, Newgrange, located 8 km (5.0 mi) to the west of the town centre. Other tourist sites in the area include:

- Millmount Fort and museum

- Saint Laurence Gate barbican gate c. 1300s

- John Philip Holland memorial (sculpture commemorating submarine inventor)

- Boyne Viaduct

- John Jameson's residential home (not open to the public), and a Jameson distillery trail of malthouses in the town.

- Battle Of The Boyne Site, visitors centre

- Éamonn Ceannt's school (formerly St Joseph's CBS now operates as Scholars Hotel)

- Beaulieu House and Gardens

- Mellifont Abbey

- Townley Hall nature trail and woods

- Princess Grace Rose Garden at St. Dominic's Park

- St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church, which houses a shrine of Oliver Plunkett

- St Peter's Church of Ireland church, on Peter's Hill

- Highlanes Gallery

- Augustinian Church 'The Passion Window' Harry Clarke Studio[43]

Industry and economy

[edit]There are several international companies based in the Drogheda area. Local employers include Coca-Cola International Services, State Street International Services, Natures Best, Yapstone Inc,[44][45] the Drogheda Port Company, Glanbia and Flogas (only Flogas Terminals since 2025)

Drogheda also has a history of brewing and distilling, with companies Jameson Whiskey, Coca-Cola, Guinness, Jack Daniel's all having previously produced (or still producing) their products in or near the town. These include the Boann distillery and brewery, Slane Whiskey (a Jack Daniel's-owned company), Listoke House, Dan Kellys (cider), and Jack Codys. The town formerly distilled Prestons whiskey, a Jameson Whiskey brand; Cairnes Beer,[46] founded locally and sold to Guinness; and Coca-Cola concentrate.

Drogheda in recent years has seen growth in the construction of apartments, commercial property and houses. Drogheda in 2024 is expected to receive over 1000 newly constructed homes varying between housing types and prices.[citation needed]

Transport, communications and amenities

[edit]

Road links and infrastructure

[edit]Drogheda is located close to the M1 (E1 Euro Route 1) (main Dublin – Belfast motorway). The Mary McAleese Boyne Valley Bridge carries traffic from the M1, across the River Boyne, three km (1.9 mi) west of the town. It was opened on 9 June 2003 and is the longest cable-stayed bridge in Ireland. The town's postcode, or eircode, is A92.

Railway

[edit]Drogheda acquired rail links to Dublin in 1844, Navan in 1850 and Belfast in 1852. Passenger services between Drogheda and Navan were ended in 1958, however the line remains open for freight (Tara Mines/Platin Cement) traffic. In 1966 Drogheda station was renamed "MacBride". Drogheda railway station opened on 26 May 1844.[47]

The station has direct trains on the Enterprise northbound to Dundalk, Newry, Portadown and Belfast Grand Central, and southbound to Dublin Connolly. 1 Train a day to Belfast skips Drogheda.

A wide variety of Iarnród Éireann commuter services connect southbound to Balbriggan, Malahide, Howth Junction, Dublin Connolly, Tara Street, Dublin Pearse, Dún Laoghaire, Bray, Greystones, Wicklow, and Wexford. The DART is planned to be extended to Drogheda in the late 2020s or 30s as part of the DART+ program.

Bus transport

[edit]Drogheda's bus station is located on Donore Road. Past Bus Éireann routes included the 184 to Garristown and 185 to Bellewstown. Currently there are buses to Monaghan and Dublin.

Administration

[edit]

Drogheda was one of ten boroughs retained under the Municipal Corporations (Ireland) Act 1840. Under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, the area became an urban district,[48] while retaining the style of a borough corporation.[49]

Drogheda Borough Corporation became a borough council in 2002.[50] On 1 June 2014, the borough council was dissolved and the administration of the town was amalgamated with Louth County Council.[51][52] It retains the right to be described as a borough.[53] The chair of the borough district uses the title of mayor, rather than Cathaoirleach.[54]

As of the 2019 Louth County Council election, the borough district of Drogheda contains the local electoral areas of Drogheda Urban (6 seats) and Drogheda Rural (4 seats), electing 10 seats to the council.[55]

The parliamentary borough of Drogheda returned two MPs to the Irish House of Commons until 1801. Under the Act of Union, the parliamentary borough returned one MP to the United Kingdom House of Commons, until its abolition under the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885. It was thereafter represented by the South Louth from 1885 to 1918, by County Louth from 1918 to 1922, by Louth–Meath from 1921 to 1923, and by the Dáil constituency of Louth from 1923 to the present.

Media

[edit]The local newspapers are the Drogheda Leader and the Drogheda Independent and known locally as The Leader and D.I.. Both newspapers are published weekly. The office of The Drogheda Independent is at 9 Shop Street and The Drogheda Leader's offices are at 13/14 West Street.

The local radio station is LMFM, broadcasting on 95.8 FM. The headquarters of LMFM is on Marley's Lane on the south side of the town.

Hospitals and health care

[edit]Drogheda is a regional centre for medical care. Its main hospital is Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, a public hospital located in the town. and is part of the Louth Meath Hospital Group. Facilities include a 24-hour emergency department for the populations of County Louth, County Meath and the North-East of Ireland. The hospital provides 340 beds, of which 30 are reserved for acute day cases.[56]

Education

[edit]There are seven secondary schools situated in Drogheda. St. Joseph's secondary school in Newfoundwell is an all-boys school, as is St. Marys Diocesan School on Beamore Rd. The Sacred Heart School,[57] situated in Sunnyside Drogheda, is an all-girls school. The Drogheda Grammar school, located on Mornington Road, St. Oliver's Community College,[58] on Rathmullen Road, and Ballymakenny College, on the Ballymakenny Road, are mixed schools. Our Lady's College,[59] in Greenhills is an all-girls school. There is also Drogheda Institute for Further Education (DIFE), a third-level college situated in Moneymore townland.

Climate

[edit]Drogheda has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb).

| Climate data for Drogheda | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.6 (47.5) |

13.2 (55.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.6 (51.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.0 (46.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 62.3 (2.45) |

54.2 (2.13) |

55.6 (2.19) |

53.6 (2.11) |

65.4 (2.57) |

68.1 (2.68) |

73.3 (2.89) |

77.1 (3.04) |

68.2 (2.69) |

83.8 (3.30) |

80.9 (3.19) |

74.4 (2.93) |

816.9 (32.17) |

| Source: Weather.Directory[60] | |||||||||||||

Sport

[edit]The town's association football team, Drogheda United, was formed in 1919, and their home matches are played at Head In The Game Park. Nicknamed "The Drogs", they currently compete in the League of Ireland Premier Division, which they won for the first time in 2007. The club achieved success by winning the FAI Cup in 2005 and 2024, and back to back Setanta Sports Cup successes in 2006 and 2007, along with the 2012 EA Sports Cup. The Drogs came close to UEFA Champions League qualification on 2 occasions, in 2008 and 2013. They also narrowly missed out on a UEFA Cup place twice, in 2006 and 2007. Since their formation, the club have won 12 major honours. In 2011, Drogheda became the sister club of Turkish club Trabzonspor due to their matching colours, and the town's history of Ottoman assistance during the Great Famine. They are also the sister club of English club Walsall and Danish club Silkeborg through their shared ownership through Trivela Group. As cup winners, the Drogs will compete in the preliminary rounds of the UEFA Conference League in July 2025.

In rugby union, the local Boyne RFC team was formed in 1997 from the amalgamation of Delvin RFC and Drogheda RFC. As of 2010[update], the men's 1st XV team were playing in the Leinster J1 1st division.

Town twinning

[edit]- Bronte, Italy[61]

- Saint-Mandé, France[62]

- Salinas, California, United States[63]

Notable people

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2020) |

Arts and media

[edit]- Yasmine Akram, comedian and actress in Sherlock

- Pierce Brosnan, actor, film producer and environmentalist was born in Drogheda[64][65]

- Eamonn Campbell, member of The Dubliners

- Alison Comyn, journalist and broadcaster

- Susan Connolly, poet, Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship 2001

- Daniele Formica, actor, stage director and playwright was born in Drogheda

- Angela Greene, poet, Patrick Kavanagh Award 1988, Salmon Press

- Michael Holohan, composer, member and former chair of Aosdána

- Jonathan Kelly, singer-songwriter

- Evanna Lynch, actress known for her role as Luna Lovegood in the Harry Potter films

- Colin O'Donoghue, actor known for his role of Captain Hook/Killian Jones in the American TV Show Once Upon a Time

- Hector Ó hEochagáin, broadcaster and podcaster

- Offica, drill rapper

- Deirdre O'Kane, actress and casting director

- Eliza O'Neill, actress.

- Paddy McCabe, singer.

- John Boyle O'Reilly, poet and novelist, member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

- Nano Reid, painter of landscapes, particularly Drogheda, the Boyne Valley and surrounding areas

- Fiachra Trench, composer. Penned the string arrangement for fairytale of New York, and wrote music for many Hollywood films

Politics and diplomacy

[edit]- Éamonn Ceannt 1916 Rising Leader – secondary school student in St Joseph CBS Drogheda

- Damien English, Minister of State at the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment and TD for Meath West

- William Hughes, Irish-born US senator from New Jersey

- Alison Kelly, Irish ambassador to Israel

- Tony Martin, Canadian social democratic legislator

- Dominic McGlinchey, INLA leader, assassinated 10 February 1994

- Mairead McGuinness, European Finance Commissioner and Fine Gael MEP

- Ged Nash, Irish Politician, Labour Party. Former Mayor of Drogheda 2004–2005. Served as Minister of State for Business and Employment from 2014 to 2016. He was a Senator for the Labour Panel from 2016 to 2020. Currently TD 2020–present (Previously 2011–2016)

- Geraldine Byrne Nason diplomat, Irish Ambassador to the United Nations

- John Neary Diplomat. Ambassador to the Netherlands

- Paddy O'Hanlon, a former Nationalist MP for South Armagh

- Henry Singleton, judge and friend of Jonathan Swift, was a lifelong resident of Drogheda

- Peadar Toibin, TD for Meath West and leader of Aontú

- T. K. Whitaker, former Irish economist who wrote the Programme for Economic Expansion[66]

Military

[edit]- John Barrett Captain of HMS Minotaur (1793) and HMS Africa (1781)

- George Forbes, 3rd Earl of Granard Naval Officer

- William Kenny, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Thomas Charles Wright Admiral and Genera A founder of the Ecuadorian Navy/

Academia and science

[edit]- James Cullen, mathematician who discovered what are now known as the Cullen numbers.

- John Philip Holland, inventor of the modern-day submarine.

- Thomas McLaughlin ESB founder and first CEO. Built the Shannon Hydro Electric Plant.

- Michael Scott, architect who designed Busáras and the Abbey Theatre

Religion

[edit]- James Chadwick, theologian, lyricist and Archbishop of Newcastle and Hexham

- Patrick Curtis Archbishop of Armagh, Spymaster for the Duke of Wellington in the Peninsular War. No 1 on Napoleon's most wanted list.

- Thomas Lancaster, bishop, buried at St. Peter's Church

Sport

[edit]- Keane Barry, professional PDC darts player[67]

- Tommy Breen, Manchester United goalkeeper

- Gavin Brennan, midfielder for Warrenpoint Town, Drogheda United and Shamrock Rovers. Brother of footballer Killian Brennan.

- Killian Brennan, midfielder with several League of Ireland clubs, and winner of 3 League of Ireland titles, 3 FAI Cups and 5 League Cups

- Lukas Browning Lagerfeldt, footballer

- Tommy Byrne, former racing driver, raced briefly in Formula 1 in 1982[68][69]

- Tony Byrne, bronze medal winner for Ireland 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne in the lightweight division.

- Megan Campbell, Liverpool association footballer

- Jerome Clarke, former Drogheda United forward, earned one cap for the Republic of Ireland.

- Nick Colgan, goalkeeper for Chelsea, Hibernian and the Republic of Ireland.

- Barry Conlon, former Manchester City Striker

- Daryl DeLeon, Filipino-British racing driver

- Mick Fairclough, Former Irish International (English Premier League of that era)

- Evan Ferguson, professional footballer for A.S. Roma in the Seria A

- Bernard Flynn, member of the Meath football team during the 1980s and 1990s

- Paddy Gavin, former full-back for Dundalk, Doncaster Rovers and Republic of Ireland B

- Deirdre Gogarty, 1997 Women's International Boxing Federation (WIBF) featherweight world champion.

- James Hand, footballer for Huddersfield Town

- Ian Harte, former footballer with several English clubs and the Republic of Ireland national football team

- Gary Kelly, football player and charity campaigner.

- Colin Lowth, an Olympic swimmer who represented Ireland at the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney.

- David McAllister, midfielder for Sheffield United, Shrewsbury Town and Stevenage.

- Shane Monahan, Professional rugby player, Gloucester, Leinster, Munster, Connaught, Ireland U-21s International.

- Des Smyth, professional golfer, vice-captain on the winning Ryder Cup team in 2006

- Steve Staunton, former Liverpool and Aston Villa defender and Republic of Ireland captain and manager was born there

- Gary Tallon, midfielder for Mansfield Town

- Kevin Thornton, former footballer with several English clubs and the Republic of Ireland under 21s

- Sean Thornton, former footballer with several English clubs and the Republic of Ireland under 21 national team, former Sunderland Player of the Year

Other

[edit]- George Drumgoole Coleman, architect who played an instrumental role in the design and construction of much of the civil infrastructure in early Singapore

- Sir John Lumsden, founder of St John Ambulance Ireland

- Jill Meagher, crime victim

Freedom of the Town

[edit]The following people have received the Freedom of the Town of Drogheda.

- Charles Stewart Parnell: 1884.[70]

- Éamon de Valera: July 1933.[71]

- Pope John Paul II: 29 September 1979.[72]

- John Hume: 14 May 2001.[73]

- Father Iggy O’Donovan: 23 October 2013.[74]

- Michael D. Higgins: 22 May 2015.[75]

- Seamus Mallon: 8 June 2018.[76]

- Geraldine Byrne Nason: 10 January 2020.[77]

- Brother Edmund Garvey, the former Head of the Christian Brothers Order, was awarded the Freedom of Drogheda in 1997. Following outrage over the fact that when he was Head of the Order he enacted a legal strategy as head of the Congregation making it more difficult for survivors of those who were sexually abused as Children to pursue Civil cases against the Order, a campaign commenced on LMFM on the show of the late Michael Reade supported by some elected members of Louth County Council and Drogheda Borough Council who voted by 5 votes to 4 with 1 abstention to rescind Garvey's name in September 2023. Legal advice provided from the then CE Joan Martin was than the elected members could be sued if they voted as allowed under the local government act and ignored her advice. They were not sued. However, Garvey's name remains on the list of the Freedom of Drogheda on the Louth County Council website with a codicil that elected members voted to remove the name but that the Staff opposed its removal.[78]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Johnston, L. C. (1826). History of Drogheda: from the earliest period to the present time. Drogheda. p. 37. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Population Density and Area Size 2016 by Towns". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Cromwell back at gates of Drogheda – demanding a city". Independent.ie. 2 December 2017. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d "F1015: Population and Average Age by Sex and List of Towns (number and percentages), 2022". Census 2022. Central Statistics Office. April 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ See http://www.cso.ie/census Archived 9 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine and http://www.histpop.org Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine for post 1821 figures, 1813 estimate from Mason's Statistical Survey. For a discussion on the accuracy of pre-famine census returns see J.J. Lee "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses", Irish Population, Economy and Society, eds. J.M. Goldstrom and L.A. Clarkson (1981) p.54, and also "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850" by Joel Mokyr and Cormac Ó Gráda in The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Nov. 1984), pp. 473–488.

- ^ "Drogheda (Ireland) Agglomeration". City Population. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Stout, G. 2002 Newgrange and the Bend of the Boyne. Cork University Press.

- ^ Bennett, I. (ed) 1987–2004 Excavations : Summary accounts of archaeological excavations in Ireland. Bray.

- ^ The Hidden Places of Ireland 190443410X David Gerrard – 2004 -"Two minutes from the centre of Drogheda. in the old townland of Mell."

- ^ Bradley, J. 1978 'The Topography and Layout of Medieval Drogheda', Co. Louth Archaeological and Historical Journal, 19, 2, 98–127.

- ^ Bennett op cit.

- ^ Archaeology No. 5257: The medieval walls of Drogheda

- ^ "The Bullring - from the Normans to Poyning's Law and Ollie's Pub". Drogheda Life. 18 August 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ Bradley op cit 105

- ^ NLI. MS. 716, copy of map by Daniel O'Brien, c. 1780

- ^ Fabyan, Robert; Ellis, Henry (1811). The new chronicles of England and France, in two parts: by Robert Fabyan. Named by himself The concordance of histories. Reprinted from Pynson's edition of 1516. The first part collated with the editions of 1533, 1542, and 1559; and the second with a manuscript of the author's own time, as well as the subsequent editions: including the different continuations. To which are added a biographical and literary preface, and an index. Robarts – University of Toronto. London : Printed for F.C. & J. Rivington [etc.]

- ^ Antonia Fraser, Cromwell, our chief of men (London, 1973)

- ^ Cromwell letter to William Lenthall (1649)

- ^ "The Tholsel, West Street, Shop Lane, Moneymore, Drogheda, Louth". National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ (30 Geo. 3. c. 39 (I))

- ^ "Entry for Drogheda in Lewis Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1837)". Libraryireland.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ The Book of Public Arms: A Cyclopædia of the Armorial Bearings, Heraldic Devices, and Seals, as Authorized and as Used, of the Counties, Cities, Towns, and Universities of the United Kingdom. Derived from the Official Records. (1894:3). United Kingdom: T.C. & E.C. Jack.

- ^ John D'Alton, The History of Drogheda: With Its Environs, and an Introductory Memoir of the Dublin and Drogheda Railway (1844), p. 138.

- ^ Comyn, Alison (31 March 2010). "PRESIDENT SPARKS STAR AND CRESCENT DEBATE". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ Murray, Ken (25 March 2010). "President tells Turks an anecdote of myth not fact". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2010. "Liam Reilly, an administrator with the Old Drogheda Society based in the town's Millmount Museum, said last night the comments were incorrect. 'There are no records with the Drogheda Port Authority of this ever happening. Drogheda historians can trace the star and crescent back to 1210 when the British governor of Ireland, King John Lackland, granted the town its first charter,' he said"[unreliable source?] "Ottoman aid to the Irish to hit the big screen". TodaysZaman. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014."New evidence shows Turkey delivered food to Ireland during the famine". IrishCentral.com. 2 June 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ Murray, Ken (1 June 2010). "Role of Turkey during Famine clarified". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Ireland remembers how 19th century aid from Ottoman sultan changed fate of thousands | Daily Sabah". Ireland remembers how 19th century aid from Ottoman sultan changed fate of thousands. 16 February 2020. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Remembering Pope John Paul II's 1979 visit to Ireland (PHOTOS)". IrishCentral.com. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Doherty, Christine (6 January 2010). "Drogheda was safe place for Pope to visit". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ McGarry, Patsy (29 November 2016). "Pope's visit to Ireland will not draw the 1979 crowds of 2.7m". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "29 September 1979: Mass in Drogheda – Dublin | John Paul II". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Vatican. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Dangerous structure notice is served on two Narrow West Street properties". Drogheda Independent. 25 February 2017. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "Councillors in favour of closing West Street to traffic". Drogheda Life. 13 May 2020. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Russell, Cliodhna (18 February 2016). "Planning 'neglect' has made Drogheda a town that has lost its 'heart'". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Louth Forward Planning Office (June 2018). Westgate Vision: A Townscape Recovery Guide. Dundalk: Louth County Council. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "Area Profile For Town – Drogheda Legal Town and its environs" (PDF). Central Statistics Office. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Sapmap Area – Settlements – Drogheda". Census 2016. Central Statistics Office. April 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Interactive Data Visualisations | CSO Ireland". visual.cso.ie. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Drogheda to host Fleadh Cheoil". Irish Independent. 18 March 2017. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ Noel Cosgrave. "Drogheda Samba Festival". Droghedasamba.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ "Music at the Gate – Drogheda | Music at Laurence's gate in Drogheda". Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Spearman, Andy. "Drogheda Life | Drogheda allocated funding to become a tourist 'Destination Town'". Drogheda Life. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Augustinian Church, Drogheda". Tripadvisor. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Contact Us – YapStone, Payment Service Provider". Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "YapStone Names Daniel Issen as Chief Technology Officer". www.businesswire.com. 13 April 2015. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Cairnes Ltd – Brewery History Society Wiki". Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 82. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

- ^ Clancy, John Joseph (1899). A handbook of local government in Ireland: containing an explanatory introduction to the Local Government (Ireland) Act, 1898: together with the text of the act, the orders in Council, and the rules made thereunder relating to county council, rural district council, and guardian's elections: with an index. Dublin: Sealy, Bryers and Walker. p. 426.

- ^ Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, s. 22: County districts and district councils (61 & 62 Vict., c. 37 of 1898, s. 22). Enacted on 12 August 1898. Act of the UK Parliament. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 3 November 2022.

- ^ Local Government Act 2001, 6th Sch.: Local Government Areas (Towns) (No. 37 of 2001, 6th Sch.). Enacted on 21 July 2001. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 3 August 2022.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 24: Dissolution of town councils and transfer date (No. 1 of 2014, s. 24). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 21 May 2022.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014 (Commencement of Certain Provisions) (No. 3) Order 2014 (S.I. No. 214 of 2014). Signed on 22 May 2014 by Phil Hogan, Minister for the Environment, Community and Local Government. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 3 November 2022.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 19: Municipal districts (No. 1 of 2014, s. 19). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 5 September 2020.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 37: Alternative titles to Cathaoirleach and Leas-Chathaoirleach, etc. (No. 1 of 2014, s. 37). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 3 November 2022.

- ^ County of Sligo Local Electoral Areas and Municipal Districts Order 2018 (S.I. No. 632 of 2018). Signed on 19 December 2018. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, Drogheda". www.hse.ie. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Sacred Heart Secondary School – Principal's Welcome". www.sacredheart.ie. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Home Page". www.socc.ie. Archived from the original on 18 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Home". www.ourladys.ie. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Drogheda Weather & Climate Guide". Weather.Directory. Retrieved 26 July 2025.

- ^ "SEI GRADI DI SEPARAZIONE – Gli incroci del destino: Bronte, l'ammiraglio Nelson e…". lalampadina.net (in Italian). La Lampadina. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ "Standing tall with St Mande". independent.ie. Drogheda Independent. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ "Sister Cities". cityofsalinas.org. City of Salinas. 15 July 2016. Archived from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ "The Official Pierce Brosnan site". 2 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Sanwari, Ahad (12 September 2023). "Pierce Brosnan - Biography". Hello!. Retrieved 17 May 2025.

- ^ "TK Whitaker recalls his childhood in Paradise – Independent.ie". 28 February 2003. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Keane Barry". PDC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ O'Rourke, Steve (6 June 2016). "'Better than Senna' – Tommy Byrne was the greatest racing driver you've probably never heard of". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Clarke, Donald. "Crash and Burn review: Tommy Byrne – Far beyond driven". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Parnell Silver Caskett 1884" (PDF). 100 Objects. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "President de Valera to be honoured with town freedom". Today UK News. 23 August 2020. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "When love came to town". www.irishidentity.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Drogheda honour for John Hume". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ McGarry, Patsy. "Fr Iggy O'Donovan to be awarded Freedom of Drogheda". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Ireland, Office of the President of. "Diary President Is Conferred With The Freedom Of Drogheda". president.ie. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ McMahon, Aine. "Séamus Mallon awarded freedom of Drogheda despite Sinn Féin objections". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Geraldine to gain Freedom of Drogheda in January event". Drogheda Independent. 4 January 2020. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "Cllr's vote to remove freedom of Drogheda from Brother Garvey". IrishTimes. 4 September 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Garvey decides not to sue Council". RTE. 29 November 2023.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Tallaght, which also does not have city status, has about 20,000 more inhabitants than Drogheda although whether or not it can be considered a town is up for debate.

Further reading

[edit]- Quane, Michael (1963). "Drogheda Grammar School". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society. 15 (3): 207–248. doi:10.2307/27729054. JSTOR 27729054.

External links

[edit]Drogheda

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Topography

Drogheda is positioned on the east coast of Ireland, primarily within County Louth with its southern extents extending into County Meath, along the strategic Dublin-Belfast corridor. The town lies approximately 55 kilometres north of Dublin and 121 kilometres south of Belfast via the M1 motorway.[9][10] Its geographical coordinates are roughly 53.72° N latitude and 6.35° W longitude.[11] The settlement straddles the River Boyne near its estuary, about 6.5 kilometres upstream from the Irish Sea, with the river serving as a natural divide between the northern and southern parts of the town.[12] The local elevation averages 28 metres above sea level, featuring modest topographic variations that include gentle slopes and low hills, such as Millmount rising to approximately 31 metres.[13][14] The surrounding terrain comprises low-lying coastal plains with undulating ground, influenced by the lowland character of the Boyne Valley's lower reaches, supporting a mix of urban expansion and agricultural land use.[15]

Climate

Drogheda experiences a temperate oceanic climate classified as Cfb in the Köppen system, featuring mild year-round temperatures moderated by the Atlantic Ocean and prevailing westerly winds, with no extreme heat or cold due to the Gulf Stream's influence.[16][17] Average annual temperatures hover around 10°C, with highs rarely surpassing 22°C in summer and lows seldom dropping below -2°C in winter, based on historical data from 1980 to 2016 incorporating nearby stations and reanalysis models.[15] Precipitation is abundant and evenly distributed, totaling approximately 700–850 mm annually, with November and October as the wettest months averaging nearly 75 mm each, while April is driest at about 43 mm; rain falls on roughly 150–200 days per year, often as light drizzle under overcast skies that cover 60–70% of the time in winter.[15][16] Winds average 12–16 km/h, strongest in winter, contributing to a humid environment with relative humidity consistently above 80%.[15] The following table summarizes average monthly high and low temperatures (in °C) and precipitation (in mm), derived from modeled historical observations:| Month | Avg. High (°C) | Avg. Low (°C) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 8 | 3 | 66 |

| February | 8 | 3 | 51 |

| March | 9 | 3 | 48 |

| April | 12 | 5 | 43 |

| May | 15 | 7 | 46 |

| June | 17 | 10 | 51 |

| July | 19 | 12 | 46 |

| August | 19 | 12 | 58 |

| September | 16 | 9 | 56 |

| October | 13 | 7 | 74 |

| November | 10 | 5 | 74 |

| December | 8 | 3 | 69 |

History

Early Settlement and Pre-Norman Era

Archaeological evidence indicates human activity in the Drogheda area dating back to the Neolithic period, with a notable stone tool known as the "Drogheda Flake," dated to approximately 3400 BC, discovered by Professor Frank Mitchell, suggesting Middle Stone Age utilization of local resources.[4] Further, E-ware pottery from Bordeaux, unearthed at Colpe in 1988, points to pre-Norman European trade connections along the River Boyne.[4] However, these finds reflect sporadic or regional prehistoric engagement rather than organized settlement at the core site of modern Drogheda, which lies at the Boyne's estuary ford. The surrounding Boyne Valley features major Neolithic monuments upstream, such as passage tombs at Brú na Bóinne circa 3200 BC, but no comparable structures have been identified directly at Drogheda. In the early historic period (circa 400–1169 AD), the Drogheda vicinity hosted dispersed rural settlements, evidenced by ringforts, souterrains, and monastic sites within 5 km, alongside stray artifacts including penannular brooches, bronze pins, and a coin hoard dated around 905 AD.[18] Viking fleets navigated the Boyne in the 9th century, with associated activity at nearby Knowth, but no archaeological confirmation exists for a Viking settlement or longphort at Drogheda itself.[18] Documentary and excavation records reveal no pre-Norman urban foundation or permanent town at the site, with earlier claims of such dismissed due to unsubstantiated place-name interpretations.[18] [19] The Millmount mound, a prominent local feature, has been speculatively linked to prehistoric origins as a possible Bronze Age barrow or megalithic structure, potentially over 4,000 years old, though lacking definitive excavation evidence beyond a "jumble of stones" noted in limited probes.[20] Legends attribute it to early Celtic exploitation and burial of the mythical poet Amergin, but these remain unverified by empirical data.[4] The site's strategic ford on the Boyne likely drew intermittent use for crossings and trade under tribal control, such as the Conaill Muirthemhne, fostering regional rather than localized permanence until the Anglo-Norman era.[18]Medieval Development

Drogheda emerged as a key Anglo-Norman settlement in the late 12th century, with two distinct boroughs developing on either side of the River Boyne: one in the lordship of Meath to the south and the other in Uriel (later County Louth) to the north.[21] The southern borough received its earliest known charter from Walter de Lacy, son of Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath, in 1194, establishing formal borough rights and promoting settlement and trade.[21] [22] Similarly, Bertram de Verdun, a prominent Anglo-Norman lord, granted a charter to the northern borough around the same period, fostering parallel growth as a strategic river port within the English Pale.[21] By the early 13th century, Drogheda had solidified its role as a defended trading hub, with the construction of stone town walls enclosing approximately 113 acres completed by the Anglo-Normans in 1334.[23] These fortifications, standing 5 to 7 meters high and 1 to 2 meters thick, featured battlements, an arcaded wall-walk, eight main gates, and at least four postern gates, providing robust defense against incursions while delineating the urban core.[21] Prominent surviving elements include St. Laurence's Gate, a 13th-century barbican serving as a fortified entrance on the northern side.[23] The dual boroughs were formally united by royal charter from King Henry IV in 1412, enhancing administrative cohesion and economic integration.[21] Religious institutions flourished within the walled town, reflecting medieval piety and patronage. Dominican, Augustinian, and Franciscan friaries were established inside the defenses, alongside hospitals like that founded by Ursus de Swemele in the early 13th century near the west gate.[24] Economically, Drogheda functioned as a vital port exporting agrarian products such as grain and hides from its hinterland, supporting cross-channel trade with England and sustaining a growing merchant class amid the Pale's defensive priorities.[25] The town's strategic position facilitated military logistics, as evidenced by its resilience during invasions, including Edward Bruce's assault in 1317.[21]Siege of Drogheda (1649)

The Siege of Drogheda took place from 3 to 11 September 1649, as part of Oliver Cromwell's campaign to conquer Ireland for the English Commonwealth following the execution of Charles I. The town, a fortified Royalist stronghold on the River Boyne, was held by a garrison of approximately 3,000 soldiers, comprising English Royalists and Irish Confederates under the command of Sir Arthur Aston.[26] Cromwell's Parliamentarian forces, veterans of the New Model Army numbering around 12,000 (8,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry) with heavy siege artillery, arrived after securing Dublin and sought to eliminate this threat to prevent Royalist concentration north of the Boyne.[27] Upon arrival, Cromwell demanded unconditional surrender, citing the recent fall of Dublin and warning of severe consequences for resistance; Aston refused, confident in the town's defenses including walls, bastions, and the Millmount fort.[28] Over the following week, Cromwell positioned batteries and bombarded key points, creating breaches in the southern walls by 10 September. On 11 September, Parliamentarian troops stormed the breaches in two assaults; the first was repulsed with heavy fighting, but the second succeeded, forcing defenders to retreat into the town center, Millmount, and St. Peter's Church steeple.[28] Cromwell ordered no quarter for those bearing arms, a policy rooted in contemporary siege warfare to compel swift surrenders and deter prolonged rebellion amid the Irish Confederate and Royalist alliance's prior atrocities in the 1641 uprising.[28] His troops killed around 2,000 defenders during the initial storming, with further executions at Millmount where retreating soldiers were put to the sword; approximately 100 soldiers sheltering in St. Peter's steeple were burned when the structure was set alight after refusal to surrender.[28] Aston was killed, reportedly bludgeoned with his own wooden leg by soldiers. Total enemy military casualties reached about 3,000, with Cromwell's losses under 100 killed.[28] [5] Contemporary accounts, including Cromwell's letter to Parliament Speaker William Lenthall dated 17 September, emphasize that killings targeted armed combatants to prevent future bloodshed, framing the outcome as divine judgment on the garrison for past "barbarous" acts.[28] Estimates of non-combatant deaths vary; chaplain Hugh Peters reported 3,552 total killed, with roughly 2,800 soldiers, implying around 750 civilians or unarmed, though primary evidence indicates most townsfolk fled or were spared if not resisting, challenging later narratives of indiscriminate civilian massacre.[5] The garrison's elite status—described by Cromwell as the "flower" of the Royalist army—made its destruction strategically decisive, facilitating subsequent advances and contributing to the rapid collapse of organized resistance in eastern Ireland.[28]Interpretations and Controversies of the Siege

Oliver Cromwell justified the slaughter following the fall of Drogheda on September 11, 1649, as divine retribution against the garrison for their role in the 1641 Irish rebellion, during which thousands of Protestant settlers had been massacred.[28] In a letter to Speaker William Lenthall dated September 16, 1649, Cromwell reported that approximately 2,000 enemy combatants were killed within the town, with an additional 300 who had retreated to St. Peter's Church steeple either burned or put to the sword, estimating total military losses at around 3,000.[29] He emphasized that his forces showed mercy where possible but denied quarter to those who resisted after the breach, aligning with contemporary military norms for stormed fortifications where defenders refusing surrender often faced execution to deter prolonged sieges.[26] Debates persist over the extent of civilian casualties, with traditional accounts, particularly in Irish historiography, claiming thousands of non-combatants, including women and children, were systematically massacred, portraying the event as an ethnic or religious atrocity.[30] Cromwell's letter makes no mention of deliberate civilian killings, focusing instead on soldiers, and contemporary Parliamentary reports, such as from chaplain John Hewson, corroborate primarily military deaths without evidence of ordered civilian executions.[5] Revisionist historians like Tom Reilly argue that claims of widespread civilian slaughter lack solid contemporary substantiation, attributing later exaggerations to 18th- and 19th-century propaganda amid ongoing Anglo-Irish tensions, and note that Drogheda's municipal records from 1649 show no mass civilian absence or disruption indicative of genocide.[31] [32] The siege's brutality, while severe, reflected the reciprocal violence of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, where Irish Confederate forces had earlier employed similar tactics against Protestant garrisons, including at the Battle of Redstrand in 1647.[5] Some scholars, such as Pádraig Lenihan, contextualize Drogheda as standard 17th-century siege warfare rather than exceptional genocide, given the era's practices of no quarter post-breach to break enemy morale. However, Irish nationalist interpretations, influenced by cultural memory and potentially amplified by institutional biases in post-independence academia, emphasize it as a foundational trauma symbolizing English colonial oppression, leading to annual commemorations in Drogheda that highlight victimhood narratives.[33] In England, Cromwell's actions were often celebrated as necessary to secure Parliament's victory and suppress rebellion, with minimal contemporary outrage, though Puritan chaplains like Hugh Peter estimated total deaths at 3,552, including some civilians caught in the crossfire.[26] Modern controversies include debates over Cromwell's legacy, with calls in Ireland for apologies or statue removals dismissed by revisionists as ahistorical, prioritizing primary evidence over emotive retellings.[33] Empirical analysis favors the view that while indiscriminate violence occurred during the storming—killing perhaps hundreds of civilians alongside soldiers—no policy of targeted civilian extermination is verifiably documented, distinguishing it from later genocidal intents.[5]18th to 20th Centuries

In the 18th century, Drogheda emerged as a significant industrial center, particularly through its linen production, which had become well-established by 1760 and expanded considerably thereafter, positioning the town as Ireland's largest linen manufacturing hub by the late 1700s, surpassing even Belfast in scale.[34][35] The port, operational since at least 1790 with preserved archives documenting trade, supported this growth by facilitating exports of textiles and imports of raw materials, while architectural developments reflected prosperity, including Georgian-style buildings that contributed to the town's reputation as a "large, handsome" urban center.[36][37] The 19th century saw continued industrialization, with innovations like the 1834 flax mill mechanizing linen production and reducing reliance on traditional home spinning, though the sector faced challenges from competition and economic shifts.[38] The Great Famine of 1845–1852 severely impacted the region, causing widespread distress in Drogheda by 1847 through crop failures, disease, and unemployment; the town served as the second-largest emigration port in Ireland, with thousands departing for Britain, America, and Australia amid population declines exceeding 20% in surrounding areas due to death and exodus.[39][40] Post-famine recovery involved port enhancements and rail connections, but textile dominance waned as broader Irish economic stagnation limited sustained growth. The 20th century marked a transition from traditional industries like linen and textiles, which declined sharply after mid-century due to global competition and mechanization shifts, toward diversified manufacturing including electronics and pharmaceuticals by the late 1900s.[41] Drogheda experienced the broader turbulence of Irish independence, with local involvement in agrarian movements via publications like the Drogheda Independent, established in 1884 and aligned with the Land League's advocacy for tenant rights against absentee landlords.[42] The town avoided major conflict during the War of Independence (1919–1921) and Civil War (1922–1923), but economic stagnation persisted until post-World War II infrastructure improvements, including motorway developments, spurred modest revival; population stabilized around 20,000–25,000 by century's end, reflecting national trends of rural-to-urban migration and state-led industrialization.[38]21st Century Developments

In the early 2000s, Drogheda benefited from Ireland's Celtic Tiger economic expansion, which spurred residential and commercial development as the town positioned itself as a key commuter hub along the Dublin-Belfast corridor. Population growth accelerated, with the urban area expanding from approximately 28,000 residents in 2002 to over 30,000 by 2011, driven by inbound migration and housing construction amid low unemployment and rising property values nationwide. Infrastructure enhancements, including upgrades to the Dublin-Belfast railway line and completion of sections of the M1 motorway, improved connectivity and supported suburban expansion, particularly in the southern environs straddling Counties Louth and Meath.[43][44] The 2008 financial crisis halted much of this momentum, leading to stalled projects and economic contraction, though Drogheda's recovery aligned with Ireland's post-2010 rebound, evidenced by renewed population increases to around 44,000 by 2022 and claims of exceeding 50,000 by 2025 amid ongoing housing developments. Challenges emerged, including recurrent flooding events—such as severe inundations in 2002, 2014, 2020, and 2023—that damaged low-lying areas along the Boyne River and prompted calls for improved defenses. Urban regeneration initiatives gained traction, with projects like the Westgate 2040 scheme aiming to revitalize derelict town-center sites through mixed-use development and public realm enhancements to counter core-area decline.[45][46] A notable social disruption unfolded from 2018 onward with the escalation of a gang feud between rival factions, primarily the Price/Maguire and Lynch groups, vying for control of the local drug trade. This conflict, marked by over 70 recorded incidents including shootings, firebombings, and at least four murders—such as the 2020 abduction, killing, and dismemberment of Keane Mulready-Woods, whose body parts were discovered in Dublin—intensified violence in residential areas and drew national attention to organized crime infiltration. Gardaí interventions, including arrests and extraditions, have aimed to dismantle the networks, but the feud underscores broader challenges from Ireland's evolving illicit drug economy.[47][48][49]Demographics

Population Trends and Growth

Drogheda's population remained relatively stable at around 25,000 from the early 20th century through the mid-1990s, reflecting broader patterns of limited urbanization in provincial Irish towns prior to the economic expansion of the Celtic Tiger era.[9] This stasis contrasted with national declines during the Great Famine (1845–1852), though specific local data indicate Drogheda, as a port town, experienced emigration pressures similar to Ireland's overall 20–25% population drop between 1841 and 1851.[50] Significant acceleration began in the late 1990s, driven by Ireland's economic boom, improved transport links to Dublin, and housing development. The 1996 census recorded 25,282 residents in core Drogheda, rising to 31,020 by 2002 (a 22.7% increase) and 35,090 by 2006.[9] From 2016 to 2022, the population grew by 13% to 44,135, surpassing the national average growth of about 8% over the same period and positioning Drogheda as Ireland's largest town by population.[51][52] Over the 1996–2022 span, core Drogheda saw a 74.6% rise, while the wider metropolitan area doubled from 46,451 to 93,603, underscoring suburban expansion into adjoining Meath.[53]| Census Year | Core Drogheda Population | % Change from Previous |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 25,282 | - |

| 2002 | 31,020 | +22.7% |

| 2006 | 35,090 | +13.1% |

| 2022 | 44,135 | +25.8% (from 2006) |

Ethnic Composition and Immigration

The 2022 census enumerated 44,135 residents in Drogheda, reflecting sustained population growth driven in part by immigration.[51] As the principal urban center in County Louth, Drogheda's ethnic composition mirrors the county's profile, where White Irish individuals formed the largest group at 106,600 persons, comprising the substantial majority.[55] The next most prominent category was "Any other White background" with 11,734 persons, followed by Black or Black Irish – African (4,296), Asian or Asian Irish (Indian/Pakistani/Bangladeshi) (1,967), and Irish Travellers (930).[55] Non-Irish citizens accounted for 11% of Louth's population, totaling over 14,000 individuals, with the predominant nationalities being Lithuanian (1,817), Polish (1,734), and United Kingdom (1,688).[55] Dual Irish citizenship holders numbered 4,271 county-wide, often combining Irish with Nigerian, UK, or US nationality.[55] These patterns stem from post-2004 EU enlargement, which enabled substantial labor migration from Eastern Europe amid Ireland's economic expansion, contributing to Drogheda's 74.57% population increase from 25,282 in 1996 to 44,135 in 2022.[56] In the year preceding the census, 1,917 persons immigrated to Louth from outside Ireland, alongside 1,920 internal migrants, underscoring ongoing inflows that bolster urban centers like Drogheda.[55] Nationally, foreign-born residents reached 20% of the population by 2022, up from 17% in 2016, with EU citizens forming the largest share post-accession waves.[57] Drogheda's proximity to Dublin and industrial base have amplified its appeal for such migrants, fostering communities from Poland, Lithuania, and beyond, though precise town-level foreign-born figures remain aggregated at the county scale in available releases.[55]Religious Composition

Drogheda maintains a predominantly Roman Catholic religious composition, reflective of Ireland's historical Christian heritage, with the town serving as a center for Catholic devotion, notably housing the preserved head of St. Oliver Plunkett in St. Peter's Church since the 18th century. The 2022 census data for County Louth, encompassing Drogheda, indicates that 72% of residents identified as Roman Catholic, a decline from 82% in 2016, amid broader national trends of secularization and demographic shifts.[55] No religion accounted for 12% of the county population in 2022, up 72% from 2016 levels, while other Christian denominations such as the Church of Ireland represented 1.6%, Orthodox Christianity 1.9%, and Islam 1.6%.[55] As Louth's principal urban area with a population of 44,135 in 2022, Drogheda's profile likely mirrors these county statistics, potentially with marginally elevated non-Catholic and non-religious shares due to its higher concentration of immigrants from Eastern Europe and elsewhere.[55] Historically, the 1911 census recorded Roman Catholics at nearly 93% of Drogheda's inhabitants, underscoring the town's longstanding Catholic majority predating modern diversification.[58]Local Government and Administration

Governance Structure

Drogheda's governance is fragmented across two counties, Louth and Meath, without a single unified local authority. The northern and central portions, comprising the majority of the town's population and area, fall under Louth County Council as the Drogheda Borough District, a municipal district established in 2014 following the abolition of the standalone Drogheda Borough Council under local government reforms.[59][60] The borough district retains ceremonial privileges, including the title of mayor for its elected head, distinct from the standard cathaoirleach used elsewhere.[59] The Drogheda Borough District operates through a committee of Louth County councillors elected to represent local electoral areas within the district, including Drogheda East, Drogheda Rural, and Drogheda West. This committee convenes monthly to address district-level issues such as local infrastructure maintenance, community grants, and bye-laws, while broader county-wide decisions remain with the full Louth County Council, which consists of 29 members. The district mayor, selected annually by the committee, chairs these meetings and performs civic functions.[61][62] The southern environs of Drogheda, extending into County Meath, are administered separately by Meath County Council, primarily within the Laytown-Bettystown Municipal District. This division results in distinct planning, service delivery, and taxation structures across the boundary, complicating coordinated development. To mitigate this, Louth and Meath County Councils jointly prepare the Drogheda Local Area Plan, covering both jurisdictions to align zoning and infrastructure strategies.[9][63]Political Representation

Drogheda is represented nationally in Dáil Éireann as part of the five-seat Louth constituency, which encompasses all of County Louth.[64] The current Teachtaí Dála (TDs) for Louth, elected or re-elected following the November 2024 general election, are Paula Butterly (Fine Gael), Joanna Byrne (Sinn Féin), Erin McGreehan (Fianna Fáil), Ged Nash (Labour), and Ruairí Ó Murchú (Sinn Féin).[64] [65] At the local level, Drogheda falls under Louth County Council, which has 29 members elected across five local electoral areas (LEAs).[66] The town is primarily represented through the Borough District of Drogheda, comprising the Drogheda Urban LEA (6 seats) and Drogheda Rural LEA (5 seats), totaling 11 councillors.[66] The district elects a chairperson annually, with Labour Party councillor Michelle Hall serving as mayor for the 2025–2026 term.[67] In the June 2024 local elections, Drogheda Urban saw representation from Labour (Pio Smith), Sinn Féin (Joanna Byrne, who later vacated her seat upon election to Dáil Éireann), Independent (Kevin Callan and Paddy McQuillan), Fianna Fáil (James Byrne), and Fine Gael (Ejiro O'Hare-Stratton).[66] [68] Drogheda Rural elected candidates including Labour's Michelle Hall and Sinn Féin's Eric Donovan, reflecting a mix of party and independent voices focused on local issues such as housing and infrastructure.[66] [69] Independent candidates secured multiple seats across the district, underscoring their influence in local governance.[70]Campaign for City Status

The Drogheda City Status Group (DCSG), founded by local advocate Anna McKenna, has led efforts since at least 2024 to secure formal city status for Drogheda, arguing that the urban area's rapid expansion necessitates dedicated administrative structures.[71] The campaign emphasizes Drogheda's position as Ireland's largest town by the 2016 census and its projected growth to over 55,500 residents by 2027, excluding adjacent areas in East Meath and South Louth that push the functional population beyond 80,000.[45][72] Proponents contend this scale exceeds that of existing cities like Waterford in urban footprint, rendering current town-level governance inadequate for infrastructure, budgeting, and regional coordination.[73] Key campaign milestones include a October 6, 2025, video release by DCSG showcasing demographic data and infrastructure strains, which called for immediate government declaration of city status, establishment of a city manager, and a tailored budget to match growth demands.[74][75] This followed earlier advocacy, such as submissions to national bodies highlighting Drogheda's potential as Ireland's sixth city based on economic vitality and historical precedents.[76] Political support has intensified, with Fianna Fáil Senator Alison Comyn using her October 21, 2025, Seanad speech to propose a government task force for a 12-month roadmap to city status, citing the town's outgrown town framework and need for enhanced local authority powers.[60][77] Drogheda Mayor Darren Murphy has publicly affirmed that city status is "inevitable" amid ongoing development, urging preparation through business and civic readiness to leverage the designation for investment and services.[78] As of October 2025, no formal grant has occurred, with the campaign framing the push as essential for aligning statutory recognition with empirical urban realities rather than symbolic elevation.[79] DCSG continues advocacy via social media and public calls, prioritizing evidence-based arguments over historical claims to avoid unsubstantiated precedents.[80]Economy and Industry

Key Economic Sectors

Drogheda's economy is anchored in manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and human health and social work, reflecting its role as a regional hub in County Louth. According to the 2022 Census of Population data for Louth, the wholesale and retail trade sector employed approximately 8,200 people, comprising the largest share of county employment.[81] Manufacturing follows as a key pillar, driven by multinational operations in pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and food processing, including facilities by BD (Becton Dickinson) for oncology and radiology products before its announced closure in 2024, and Boyne Valley Group producing brands like Batchelors soups.[82][83][84] The human health and social work sector ranks prominently, bolstered by Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, a major regional facility serving north Leinster with extensive acute and emergency services. Local development plans highlight manufacturing's concentration due to IDA-supported business parks attracting high-value industries, though traditional sectors like textiles have declined since the 20th century. Retail thrives through centers like Scotch Hall, supporting consumer-oriented commerce amid population growth.[85] Emerging initiatives, such as the CORE project, aim to expand advanced manufacturing and clean energy, but current employment remains rooted in established sectors.[86]Drogheda Port and Trade

Drogheda Port, situated on the estuary of the River Boyne, has served as a key maritime gateway since medieval times, when the river functioned as a primary commercial artery for regional trade in Ireland.[87] By the early 19th century, the port facilitated significant cross-channel shipping, with the establishment of the Drogheda Steam Packet Company in 1826 enabling regular steamship services to ports in Britain and Ireland.[87] During the 1840s Irish Famine, it handled relief shipments, including Ottoman aid vessels in 1847, underscoring its role in international supply chains amid economic distress.[88] The port's infrastructure expanded to support industrial exports like textiles and agricultural goods, contributing to Drogheda's growth as an manufacturing hub by the mid-19th century.[87] In the 20th century, Drogheda Port transitioned toward bulk and general cargo handling, with Harbour Commissioners overseeing operations from their establishment under the Port of Drogheda Act of 1790 until privatization in 1997, when the Drogheda Port Company assumed management as a commercial entity.[87] Today, the port processes over 1.5 million tonnes of cargo annually, specializing in bulk, breakbulk, and project cargoes such as fertilizers, animal feeds, grains, timber, steel products, cement, and biomass fuels.[89] It accommodates vessels up to 550 ships per year, with facilities including four inner northern quays totaling 430 meters in length, cranes for heavy lifts, and port-centric warehousing for efficient logistics.[90] Principal trade routes connect to the UK, Scandinavia, and continental Europe, supporting imports for agriculture and construction while exporting Irish goods.[89] The port's operations emphasize rapid vessel turnaround and flexibility, handling specialized loads like refuse-derived fuel (RDF), solid recovered fuel (SRF), and outsized project cargoes for industries including offshore wind.[91] Its strategic location along the M1 corridor between Dublin and Belfast enhances multimodal connectivity via road and rail, bolstering regional supply chains without reliance on larger Dublin facilities.[89] Recent masterplanning focuses on sustainable expansion, including partnerships for the nearby Bremore Port development to accommodate growing freight demands.[92] Despite national port traffic declines of 10% in 2023 to 47.8 million tonnes across Ireland, Drogheda's niche in non-containerized cargoes maintains steady throughput, contributing to local employment and economic resilience.[93]Economic Challenges and Growth Constraints