Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Star and crescent

View on Wikipedia

The conjoined representation of a star and a crescent is used in various historical contexts, including as a prominent symbol of the Ottoman Empire, and in contemporary times, as a national symbol by some countries, and by some Muslims as a symbol of Islam,[1] while other Muslims reject it as an Islamic symbol.[2] It was developed in the Greek colony of Byzantium ca. 300 BC, though it became more widely used as the royal emblem of Pontic king Mithridates VI Eupator after he incorporated Byzantium into his kingdom for a short period.[3] During the 5th century, it was present in coins minted by the Persian Sassanian Empire; the symbol was represented in the coins minted across the empire throughout the Middle East for more than 400 years from the 3rd century until the fall of the Sassanians after the Muslim conquest of Persia in the 7th century.[4] The conquering Muslim rulers kept the symbol in their coinage during the early years of the caliphate, as the coins were exact replicas of the Sassanian coins.

Both elements of the symbol have a long history in the iconography of the Ancient Near East as representing either the Sun and Moon or the Moon and Venus (Morning Star) (or their divine personifications). It has been suggested that the crescent actually represents Venus,[5][6] or the Sun during an eclipse.[7] Coins with star and crescent symbols represented separately have a longer history, with possible ties to older Mesopotamian iconography. The star, or Sun, is often shown within the arc of the crescent (also called star in crescent, or star within crescent, for disambiguation of depictions of a star and a crescent side by side).[8] In numismatics in particular, the term pellet within crescent is used in cases where the star is simplified to a single dot.[9]

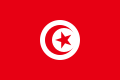

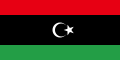

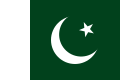

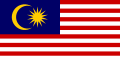

The combination is found comparatively rarely in late medieval and early modern heraldry. It rose to prominence with its adoption as the flag and national symbol of the Ottoman Empire and some of its administrative divisions (eyalets and vilayets) and later in the 19th-century Westernizing tanzimat (reforms). The Ottoman flag of 1844, with a white ay-yıldız (Turkish for "crescent-star") on a red background, continues in use as the flag of the Republic of Turkey, with minor modifications. Other states formerly part of the Ottoman Empire also used the symbol, including Libya (1951–1969 and after 2011), Tunisia (1831) and Algeria (1958). The same symbol was used in other national flags introduced during the 20th century, including the flags of Kazakhstan (1917), Azerbaijan (1918), Pakistan (1947), Malaysia (1948), Singapore (1959), Mauritania (1959), Azad Kashmir (1974), Uzbekistan (1991), Turkmenistan (1991) and Comoros (2001). In the latter 20th century, the star and crescent have acquired a popular interpretation as a "symbol of Islam",[1] occasionally embraced by Arab nationalism or Islamism in the 1970s to 1980s but often rejected as erroneous or unfounded by Muslim commentators in more recent times.[2] Unlike the cross, which is a symbol of Jesus' crucifixion in Christianity, there is no solid link that connects the star and crescent symbol with the concept of Islam. The connotation is widely believed to have come from the flag of the Ottoman Empire, whose prestige as an Islamic empire and caliphate led to the adoption of its state emblem as a symbol of Islam by association.

History

[edit]

Origins and predecessors

[edit]

Crescents appearing together with a star or stars are a common feature of Sumerian iconography, the crescent usually being associated with the moon god Sin (Nanna) and the star with Ishtar (Inanna, i.e. Venus), often placed alongside the sun disk of Shamash.[11][12]

In Late Bronze Age Canaan, star and crescent moon motifs are also found on Moabite name seals.[13]

| |

| |

| |

The depiction of the "star and crescent" or "star inside crescent" as it would later develop in Bosporan Kingdom is difficult to trace to Mesopotamian art. Exceptionally, a combination of the crescent of Sin with the five-pointed star of Ishtar, with the star placed inside the crescent as in the later Hellenistic-era symbol, placed among numerous other symbols, is found in a boundary stone of Nebuchadnezzar I (12th century BC; found in Nippur by John Henry Haynes in 1896).[15] An example of such an arrangement is also found in the (highly speculative) reconstruction of a fragmentary stele of Ur-Nammu (Third Dynasty of Ur) discovered in the 1920s.[16]

A very early depiction of the symbol (crescent moon, stars and sun disc) is found on the Nebra sky disc, dating from c. 1800 – c. 1600 BC (Nebra, Germany). A gold signet ring from Mycenae dating from the 15th century BC also shows the symbol. The star and crescent (or 'crescent and pellet') symbol appears 19 times on the Berlin Gold Hat, dating from c. 1000 BC.

Classical antiquity

[edit]Greeks and Romans

[edit]Many ancient Greek (classical and hellenistic) and Roman amulets which depict stars and crescent have been found.[17]

Mithradates VI Eupator of Pontus (r. 120–63 BC) used an eight rayed star with a crescent moon as his emblem. McGing (1986) notes the association of the star and crescent with Mithradates VI, discussing its appearance on his coins, and its survival in the coins of the Bosporan Kingdom where "[t]he star and crescent appear on Pontic royal coins from the time of Mithradates III and seem to have had oriental significance as a dynastic badge of the Mithridatic family, or the arms of the country of Pontus."[18] Several possible interpretations of the emblem have been proposed. In most of these, the "star" is taken to represent the Sun. The combination of the two symbols has been taken as representing Sun and Moon (and by extension Day and Night), the Zoroastrian Mah and Mithra,[19] or deities arising from Greek-Anatolian-Iranian syncretism, the crescent representing Mēn Pharnakou (Μήν Φαρνακου, the local moon god[20]) and the "star" (Sun) representing Ahuramazda (in interpretatio graeca called Zeus Stratios)[21][22]

By the late Hellenistic or early Roman period, the star and crescent motif had been associated to some degree with Byzantium. If any goddess had a connection with the walls in Constantinople, it was Hecate. Hecate had a cult in Byzantium from the time of its founding. Like Byzas in one legend, she had her origins in Thrace. Hecate was considered the patron goddess of Byzantium because she was said to have saved the city from an attack by Philip of Macedon in 340 BC by the appearance of a bright light in the sky. To commemorate the event the Byzantines erected a statue of the goddess known as the Lampadephoros ("torch-bearer" or "torch-bringer").[23]

Some Byzantine coins of the 1st century BC and later show the head of Artemis with bow and quiver, and feature a crescent with what appears to be a six-rayed star on the reverse.

-

A star and crescent symbol with the star shown in a sixteen-rayed "sunburst" design (3rd century BC) on the Ai-Khanoum plaque.[24]

-

Roman-era coin with Greek inscription (1st century AD) with a bust of Artemis on the obverse and an eight-rayed star within a crescent on the reverse side.

The moon-goddess Selene is commonly depicted with a crescent moon, often accompanied by two stars (the stars represent Phosphorus, the morning star, and Hesperus, the evening star); sometimes, instead of a crescent, a lunar disc is used.[26][27][28][29] Often a crescent moon rests on her brow, or the cusps of a crescent moon protrude, horn-like, from her head, or from behind her head or shoulders.[30]

-

The Moon-goddess Selene or Luna accompanied by the Dioscuri, or Phosphoros (the Morning Star) and Hesperos (the Evening Star). Marble altar, Roman artwork, 2nd century AD. From Italy.

-

The goddess Selene, illustration from Meyers Lexikon, 1890

In the 2nd century, the star-within-crescent is found on the obverse side of Roman coins minted during the rule of Hadrian, Geta, Caracalla and Septimius Severus, in some cases as part of an arrangement of a crescent and seven stars, one or several of which were placed inside the crescent.[31]

-

Coin of Roman Emperor Hadrian (r. 117–138). The reverse shows an eight-rayed star within a crescent.

-

Roman period limestone pediment from Perge, Turkey (Antalya Museum) showing Diana-Artemis with a crescent and a radiant crown.

Iran (Persia)

[edit]The star and crescent symbol appears on some coins of the Parthian vassal kingdom of Elymais in the late 1st century AD. The same symbol is present in coins that are possibly associated with Orodes I of Parthia (1st century BC). In the 2nd century AD, some Parthian coins show a simplified "pellet within crescent" symbol.[32]

-

A star and crescent appearing (separately) on the obverse side of a coin of Orodes II of Parthia (r. 57–37 BC).

-

Coin of Vardanes I of Parthia (r. c. AD 40–45)

-

Coin of the Sasanian king Kavad II, minted at Susa in 628

-

Gold coin of Khosrow II (r. 570–628).

-

Coin of Khosrow III

-

Coin of Hormizd IV

-

Silver dirham issued by Ispahbudh Khurshid of Tabaristan

-

Arab-Sassanian coin was issued, which was added with arabic writing by the Umayyads

The star and crescent motif appears on the margin of Sassanid coins in the 5th century.[4] Sassanid rulers also appear to have used crowns featuring a crescent, sphere and crescent, or star and crescent.

Use of the star-and-crescent combination apparently goes back to the earlier appearance of a star and a crescent on Parthian coins, first under King Orodes II (1st century BC). In these coins, the two symbols occur separately, on either side of the king's head, and not yet in their combined star-and-crescent form. Such coins are also found further afield in Greater Persia, by the end of the 1st century AD in a coin issued by the Western Satraps ruler Chashtana.[33] This arrangement is likely inherited from its Ancient Near Eastern predecessors; the star and crescent symbols are not frequently found in Achaemenid iconography, but they are present in some cylinder seals of the Achaemenid era.[34]

Ayatollahi (2003) attempts to connect the modern adoption as an "Islamic symbol" to Sassanid coins remaining in circulation after the Islamic conquest [35] which is an analysis that stands in stark contrast to established consensus that there is no evidence for any connection of the symbol with Islam or the Ottomans prior to its adoption in Ottoman flags in the late 18th century.[36]

Western Turkic Khaganate

[edit]Coins from the Western Turkic Khaganate had a crescent moon and a star, which held an important place in the worldview of ancient Turks and other peoples of Central Asia.[37]

Medieval and early modern

[edit]Christian and classical heraldric usage

[edit]The crescent on its own is used in western heraldry from at least the 13th century, while the star and crescent (or "Sun and Moon") emblem is in use in medieval seals at least from the late 12th century. The crescent in pellet symbol is used in Crusader coins of the 12th century, in some cases duplicated in the four corners of a cross, as a variant of the cross-and-crosslets ("Jerusalem cross").[38] Many Crusader seals and coins show the crescent and the star (or blazing Sun) on either side of the ruler's head (as in the Sassanid tradition), e.g. Bohemond III of Antioch, Richard I of England, Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse.[39] At the same time, the star in crescent is found on the obverse of Crusader coins, e.g. in coins of the County of Tripoli minted under Raymond II or III c. 1140s–1160s show an "eight-rayed star with pellets above crescent".[40]

The star and crescent combination appears in attributed arms from the early 14th century, possibly in a coat of arms of c. 1330, possibly attributed to John Chrysostom,[41] and in the Wernigeroder Wappenbuch (late 15th century) attributed to one of the three Magi, named "Balthasar of Tarsus".[42]

Crescents (without the star) increase in popularity in early modern heraldry in Europe. Siebmachers Wappenbuch (1605) records 48 coats of arms of German families which include one or several crescents.[43]

A star and crescent symbolizing Croatia was commonly found on 13th-century banovac coins in the Kingdom of Slavonia, with a two-barred cross symbolizing the Kingdom of Hungary.[44]

St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna used to have at the top of its highest tower a golden crescent with a star; it came to be seen as a symbol of Islam and the Ottoman enemy, which is why it was replaced with a cross in 1686.[45]

In the late 16th century, the Korenić-Neorić Armorial shows a white star and crescent on a red field as the coat of arms of "Illyria".

The star and crescent combination remains rare prior to its adoption by the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the 18th century.[citation needed]

-

Great Seal of Richard I of England (1198)[46]

-

Equestrian seal of Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse with a star and a crescent (13th century)

-

The crescent flag ascribed to the Hungarians against the Mongol Golden Horde in the Battle of Mohi, 1241.

-

Battle of Wadi al-Khaznadar (Battle of Homs) of 1299 (14th-century miniature)

-

Polish coats of arms, called Leliwa (1334 seal)

-

Coats of arms of the Three Magi, with "Baltasar of Tarsus" being attributed a star and crescent increscent in a blue field, Wernigerode Armorial (c. 1490)

-

Coat of arms of John Freigraf of "Lesser Egypt" (i.e. Romani/gypsy),[48] 18th-century drawing of a 1498 coat of arms in Pforzheim church.

-

Depictions of stars with crescents are a common motif on the stećak 12th to 16th century tombstones of medieval Bosnia

-

1668 representation by Joan Blaeu of Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Bosnia from 1595 Korenić-Neorić Armorial

-

The coat of arms of "Illyria" from the Korenić-Neorić Armorial (1590s)

-

Banner of Cumania, used at the coronation of Ferdinand II of Hungary in 1618 and assigned to Gáspár (Caspar) Illésházy.

-

Star and crescent on the obverse of the Jelacic-Gulden of the Kingdom of Croatia (1848)

-

Coat of arms of the noble family Slatte (1625–1699) in Sweden.

-

Coat of arms of the noble family Finckenberg (1627–1809) in Sweden.

-

Coat of arms of the noble family Boose (1642–1727) in Sweden.

-

Banner of the Zaporizhian Sich (Cossacks of Ukraine) before 1775.

Muslim usage

[edit]While the crescent on its own is depicted as an emblem used on Islamic war flags from the medieval period, at least from the 13th century although it does not seem to have been in frequent use until the 14th or 15th century,[49][50] the star and crescent in an Islamic context is more rare in the medieval period, but may occasionally be found in depictions of flags from the 14th century onward.

Some Mughal era (17th century) round shields were decorated with a crescent or star and crescent.

-

Depiction of a star and crescent flag on the Saracen side in the Battle of Yarmouk (manuscript illustration of the History of the Tatars, Catalan workshop, early 14th century).

-

A miniature painting from a Padshahnama manuscript (c. 1640), depicting Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan as bearing a shield with a star and crescent decoration.

-

A painting from a Padshahnama manuscript (1633) depicts the scene of Aurangzeb facing the maddened war elephant Sudhakar. Sowar's shield is decorated with a star and crescent.

-

Ottoman sipahis in battle, holding the crescent banner (by Józef Brandt)

-

Coat of arms of Khedivate of Egypt (1867–1914)

-

Flag of the Kingdom of Egypt (1922–1953) and co-official flag of the Republic of Egypt (1953–1958)

-

Flag of the Free Officers Movement (1949–1953) and co-official flag of the Republic of Egypt (1953–1958)

-

Flag of the Sultanate of Aceh (1496–1903)

Use in the Ottoman Empire

[edit]

The adoption of star and crescent as the Ottoman state symbol started during the reign of Mustafa III (1757–1774) and its use became well-established during the periods of Abdul Hamid I (1774–1789) and Selim III (1789–1807).[51] A decree (buyruldu) from 1793 states that the ships in the Ottoman navy fly that flag, and various other documents from earlier and later years mention its use.[51] The ultimate source of the emblem is unclear. It is mostly derived from the star-and-crescent symbol used by the city of Constantinople in antiquity, possibly by association with the crescent design (without the star) used in Turkish flags since before 1453.[52]

With the Tanzimat reforms in the 19th century, flags were redesigned in the style of the European armies of the day. The flag of the Ottoman Navy was made red, as red was to be the flag of secular institutions and green of religious ones. As the reforms abolished all the various flags (standards) of the Ottoman pashaliks, beyliks and emirates, a single new Ottoman national flag was designed to replace them. The result was the red flag with the white crescent moon and star, which is the precursor to the modern flag of Turkey. A plain red flag was introduced as the civil ensign for all Ottoman subjects. The white crescent with an eight-pointed star on a red field is depicted as the flag of a "Turkish Man of War" in Colton's Delineation of Flags of All Nations (1862). Steenbergen's Vlaggen van alle Natiën of the same year shows a six-pointed star. A plate in Webster's Unabridged of 1882 shows the flag with an eight-pointed star labelled "Turkey, Man of war". The five-pointed star seems to have been present alongside these variants from at least 1857.

In addition to Ottoman imperial insignia, symbols appear on the flag of Bosnia Eyalet (1580–1867) and Bosnia Vilayet (1867–1908), as well as the flag of 1831 Bosnian revolt, while the symbols appeared on some representations of medieval Bosnian coat of arms too.

In the late 19th century, "Star and Crescent" came to be used as a metaphor for Ottoman rule in British literature.[53] The increasingly ubiquitous fashion of using the star and crescent symbol in the ornamentation of Ottoman mosques and minarets led to a gradual association of the symbol with Islam in general in western Orientalism.[54] The "Red Crescent" emblem was used by volunteers of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) as early as 1877 during the Russo-Turkish War; it was officially adopted in 1929.

After the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the new Turkish state maintained the last flag of the Ottoman Empire. Proportional standardisations were introduced in the Turkish Flag Law (Turkish: Türk Bayrağı Kanunu) of May 29, 1936. Besides the most prominent example of Turkey (see Flag of Turkey), a number of other Ottoman successor states adopted the design during the 20th century, including the Emirate of Cyrenaica and the Kingdom of Libya, Algeria, Tunisia, and the proposed Arab Islamic Republic.

Contemporary use

[edit]National flags

[edit]The flag of Tunisia (1831) is the first to use the star and crescent design in 1831. This continues to be the Tunisian national flag post-independence. A decade later, the Ottoman flag of 1844 with a white "ay-yıldız" (Turkish for "crescent-star") on a red background continues to be in use as the flag of the Republic of Turkey with minor modifications.

Other states in the Ottoman sphere of influence using the star and crescent design in their flats such as Libya (1951, re-introduced 2011) and Algeria (1958). The modern emblem of Turkey shows the star outside the arc of the crescent, as it were a "realistic" depiction of a conjunction of Moon and Venus, while in the 19th century, the Ottoman star and crescent was occasionally still drawn as the star-within-crescent. By contrast, the designs of both the flags of Algeria and Tunisia (as well as Mauritania and Pakistan) place the star within the crescent.

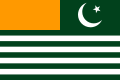

The same symbol was used in other national flags introduced during the 20th century, including the flags of Kazakhstan (1917), Azerbaijan (1918, re-introduced 1991), the Rif Republic (1921), Pakistan (1947), Malaysia (1948), Mauritania (1959), Kashmir (1974) and the partially recognized states of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (1976) and Northern Cyprus (1983). The symbol also may represent flag of cities or emirates such as the emirate of Umm Al-Quwain.

-

Flag of the Rif Republic

-

Flag of East Turkestan (1934)

-

Flag of Syrian Turkmen

-

Flag of Azad Kashmir

-

Alash Autonomy (1917)

-

Turkestan Autonomy (1917-1918)

National flags with a crescent alongside several stars:

-

Flag of Singapore (1965): crescent and five stars

-

Flag of Uzbekistan (1991): crescent and twelve stars

-

Flag of Turkmenistan (2001): crescent and five stars (representing five provinces)

-

Flag of the Comoros (2002): crescent and four stars (representing four islands)

National flags and coat of arms with star, crescent and other symbols:

-

Flag of Moldova (1990)

-

Flag of Croatia (1990)

-

Flag of Miꞌkmaꞌki (1867)

-

Flag of Moldavia (15th to 16th century)

Symbol of Islam

[edit]

By the mid-20th century, the symbol came to be re-interpreted as a symbol of Islam or the Muslim community.[55] This symbolism was embraced by movements of Arab nationalism or Islamism in the 1970s too, such as the proposed Arab Islamic Republic (1974) and the American Nation of Islam (1973).[56]

Cyril Glassé in his The New Encyclopedia of Islam (2001 edition, s.v. "Moon") states that "in the language of conventional symbols, the crescent and star have become the symbols of Islam as much as the cross is the symbol of Christianity."[1]

By contrast, Crescent magazine — a religious Islamic publication — quoted without giving names that "Many Muslim scholars reject using the crescent moon as a symbol of Islam".[2]

On February 28, 2017, it was announced by the Qira County government in Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, China that those who reported others for stitching the 'star and crescent moon' insignia on their clothing or personal items or having the words 'East Turkestan' on their mobile phone case, purse or other jewelry, would be eligible for cash payments.[57]

Municipal coats of arms

[edit]The star and crescent as a traditional heraldic charge is in continued use in numerous municipal coats of arms; notably that based on the Leliwa (Tarnowski) coat of arms in the case of Polish municipalities.

-

Coat of arms of Halle an der Saale, Germany (1327).

-

Coat of arms of Mińsk Mazowiecki, Poland.

-

Coat of arms of Przeworsk, Poland.

-

Coat of arms of Tarnobrzeg, Poland.

-

Coat of arms of Tarnów, Poland.

-

Coat of arms of Topoľčany, Slovakia

-

Coat of arms of Zagreb, Croatia.

-

Coat of arms of Mattighofen, Austria (1781)

-

Coat of arms of Oelde, Germany (1910).

-

Coat of arms of Niederglatt, Switzerland (1928)[59]

-

Coat of arms of Niederweningen, Switzerland (1928)[59]

-

Coat of arms of Drogheda, Ireland

-

Coat of arms of Algueirão-Mem Martins parish, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Aljezur parish, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Casal de Cambra parish, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Celorico da Beira municipality, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Nisa municipality, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Nossa Senhora das Misericórdias parish, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Oliveira do Bairro municipality, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Penacova municipality, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of São Brás de Alportel parish, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Sintra municipality, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Sobreda parish, Portugal

-

Coat of arms of Vouzela municipality, Portugal

Diocesan Coat of Arms

[edit]-

Coat of arms of the Archdiocese of Agaña

-

Coat of arms of the Diocese of Arlington

-

Coat of arms of the Diocese of Juneau

-

Coat of arms of the Archdiocese of Moncton

-

Coat of arms of the Eparchy of Newton

-

Coat of arms of the Archdiocese of Anchorage-Juneau

-

Coat of arms of the Diocese of Jefferson City

-

Coat of arms of the Archdiocese of Vitória da Conquista

-

Coat of arms of the Archdiocese of Cotabato

-

Coat of arms of the Territorial Prelature of Batanes

Sports Club Emblems

[edit]In rugby union, Saracens F.C. incorporates the star and crescent in its crest. Drogheda United F.C., Portsmouth F.C., and S.U. Sintrense all borrow the star and crescent from their respective towns' coats of arms. Mohammedan SC in Kolkata, India also incorporates the symbol in its crest.

-

Emblem of Saracens F.C.

Other uses

[edit]-

Post WWII flag of the Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF)

-

Flag of the Pakistan Army

-

Flag of the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity

-

Insignia of East Bengal Regiment

-

Logo of Shriners International

-

Logo of the Felicity Party of Turkey

-

Logo of the Crescent Star Party of Indonesia

Use in computer documents and printing

[edit]The symbol has a codepoint in Unicode, which is U+262A ☪ STAR AND CRESCENT. The precise form of the symbol displayed or printed depends on the computer font chosen.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Cyril Glassé, The New Encyclopedia of Islam (revised ed. 2001), s.v. "Moon" (p. 314).

- ^ a b c "Many Muslim scholars reject using the crescent moon as a symbol of Islam. The faith of Islam historically had no symbol, and many refuse to accept it." Fiaz Fazli, Crescent magazine, Srinagar, September 2009, p. 42.

- ^ Andrew G. Traver, From Polis to Empire, The Ancient World, c. 800 B.C.–A.D. 500, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, p. 257

- ^ a b "The star and crescent are common Persian symbols, being a regular feature of the borders of Sassanian dirhems." Philip Grierson, Byzantine Coins, Taylor & Francis, 1982, p118

- ^ Bradley Schaefer (21 December 1991). "Heavenly Signs". New Scientist: 48–51.

- ^ David Lance Goines (18 October 1995). "Inferential evidence for the pre-telescopic sighting of the crescent Venus".

- ^ This would explain cases where the inside curve of the crescent has a smaller radius of curvature than the outer, the opposite of what happens with the moon. Jay M. Pasachoff (1 February 1992). "Crescent Sun". New Scientist.

- ^ "There are also three cases [... viz., associated with the "Danubian Rider Religion"] where the star, figured as a radiate disc 'balancing the crescent moon', must represent Sol, balancing Luna who is represented as a crescent instead of in bust. The 'star in crescent' theme itself appears only once, on an engraved gem, accompanied by the lion and an indecipherable inscription [...] This theme is connected with the Orient and has a long history behind it in the Hittite, Babylonian, Assyrian, Sassanid and Iranian worlds. Campbell gives us valuable particulars. The heavenly bodies thus symbolized were seen as the powerful influence of cosmic fatalism guiding the destinies of men." Dumitru Tudor, Christopher Holme (trans.), Corpus Monumentorum Religionis Equitum Danuvinorum (CMRED) (1976), p. 192 (referencing Leroy A. Campbell, Mithraic Iconography and Ideology' '(1969), 93f.

- ^ e.g. Catalogue of the Greek coins in The British Museum (2005), p. 311 (index).

- ^ A similar stele found in Babylon is kept in the British Museum (no. 90837).

- ^ Michael R. Molnar, The Star of Bethlehem, Rutgers University Press, 1999, p78

- ^ "the three celestial emblems, the sun disk of Shamash (Utu to the Sumerians), the crescent of Sin (Nanna), and the star of Ishtar (Inanna to the Sumerians)" Irving L. Finkel, Markham J. Geller, Sumerian Gods and Their Representations, Styx, 1997, p71. André Parrot, Sumer: The Dawn of Art, Golden Press, 1961

- ^ Othmar Keel, Christoph Uehlinger, Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel, Fortress Press, 1998, p. 322.

- ^ A.H. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs. 3rd Ed., pub. Griffith Institute, Oxford, 1957 (1st edition 1927), p. 486.

- ^ W. J. Hinke, A New Boundary Stone of Nebuchadrezzar I from Nippur with a Concordance of Proper Names and a Glossary of the Kudurru Inscriptions thus far Published (1907), 120f. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, object nr. 29-20-1.

- ^ J. V. Canby, Reconstructing the Ur Nammu Stela, Expedition 29.1, 54–64.

- ^ Christopher A. Faraone (2018). The Transformation of Greek Amulets in Roman Imperial Times. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 40–53. ISBN 978-0-8122-4935-4.

- ^ B.C. McGing, The Foreign Policy of Mithradates VI Eupator, King of Pontus, Brill, 1986, p 97

- ^ "The star and the crescent, the emblem of the Pontus and its kings, were introduced by Mithradates and his successors to the Bosporus and appeared on Bosporan coins and locally produced jewelry. On the coins this symbol often appears near the head of a young man wearing a Phrygian cap, who is identified as either a solar deity or his deified worshipper. [...] the star and the crescent, the badge of the Pontus and its kings, shown on the Colchian amphora stamp, and appearing on engraved finger-rings discovered in this area allude to the possibility of an earlier association of the Pontic dynasty with the cult of mounted Mithra. Mithra in fact must have been one of the most venerated gods of the Pontic Kingdom, since its rulers bore the theophoric name of Mithradates [...] although direct evidence for this cult is rather meager." Yulia Ustinova, The Supreme Gods of the Bosporan Kingdom, Brill, 1998, 270–274

- ^ Strabo (12.3.31) writes that Mēn Pharnakou had a sanctuary at Kabeira in Pontus where the Pontic kings would swear oaths. Mēn Pharnakou is a syncretistic Anatolian-Iranian moon deity not directly comparable to Zoroastrian Māh. Albert F. de Jong, Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature (1997), %A9n%20Pharmakou&f=false p. 306.

- ^ "His royal emblem, an eight rayed star and the crescent moon, represented the dynasty's patron gods, Zeus Stratios, or Ahuramazda, and Mén Pharnakou, a Persian form of the native moon goddess." Andrew G. Traver, From Polis to Empire—The Ancient World c. 800 B.C.–A.D. 450, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, p. 257

- ^ "The significance of the star and crescent on royal coins has also been frequently debated. Many scholars have identified the star and the crescent as royal symbols of the Pontic kingdom. Their appearance on every royal issue suggests they were indeed important symbols, and the connection of this symbol to the royal family is definite. The nature of it, however, is still uncertain. Kleiner believed they were symbols of an indigenous god and had their origins in Persia. He associated the star and crescent with the god Men and saw them as representations of night and day (the star may be considered the sun here). Ritter, on the other hand, suggested that the star and crescent symbols derived from Perseus, just as the star symbol of the Macedonians did. […] Ma and Mithras are two other deities with whom the star and crescent symbol are associated. Olshausen believed that the star and crescent could be related to a syncretism of Pontic and Iranian iconography: the crescent for Men and the star for Ahura Mazda. Recently, Summerer has convincingly suggested that Men alone was the inspiration for the symbol on the royal coins of the Pontic kingdom. Deniz Burcu Erciyas, "Wealth, Aristocracy, and Royal Propaganda Under The Hellenistic Kingdom of The Mithradatids in The Central Black Sea Region in Turkey", Colloquia Pontica Vol.12, Brill, 2005, p 131

- ^ "Devotion to Hecate was especially favored by the Byzantines for her aid in having protected them from the incursions of Philip of Macedon. Her symbols were the crescent and star, and the walls of her city were her provenance." Vasiliki Limberis, Divine Heiress, Routledge, 1994, p 15. "In 340 B.C., however, the Byzantines, with the aid of the Athenians, withstood a siege successfully, an occurrence the more remarkable as they were attacked by the greatest general of the age, Philip of Macedon. In the course of this beleaguerment, it is related, on a certain wet and moonless night the enemy attempted a surprise, but were foiled by reason of a bright light which, appearing suddenly in the heavens, startled all the dogs in the town and thus roused the garrison to a sense of their danger. To commemorate this timely phenomenon, which was attributed to Hecate, they erected a public statue to that goddess [...]" William Gordon Holmes, The Age of Justinian and Theodora, 2003 p 5-6; "If any goddess had a connection with the walls in Constantinople, it was Hecate. Hecate had a cult in Byzantium from the time of its founding. Like Byzas in one legend, she had her origins in Thrace. Since Hecate was the guardian of "liminal places", in Byzantium small temples in her honor were placed close to the gates of the city. Hecate's importance to Byzantium was above all as deity of protection. When Philip of Macedon was about to attack the city, according to the legend she alerted the townspeople with her ever-present torches, and with her pack of dogs, which served as her constant companions. Her mythic qualities thenceforth forever entered the fabric of Byzantine history. A statue known as the 'Lampadephoros' was erected on the hill above the Bosphorous to commemorate Hecate's defensive aid." Vasiliki Limberis, Divine Heiress, Routledge, 1994, pp. 126–127. This story survived in the works, who in all probability lived in the time of Justinian I. His works survive only in fragments preserved in Photius and the 10th century lexicographer Suidas. The tale is also related by Stephanus of Byzantium, and Eustathius.

- ^ On the Ai-Khanoum plaque from Ai Khanoum, Bactria, 3rd century BC. Helios is shown separately in the form of a bust with a rayed halo of thirteen rays. F. Tissot, Catalogue of the National Museum of Afghanistan, 1931-1985 (2006), p. 42.

- ^ H. G. Liddell, A History of Rome from the earliest times to the establishment of the Empire (1857), p. 605. Cf. forumancientcoins.com.

- ^ LIMC, Selene, Luna 35.

- ^ Cohen, Beth, "Outline as a Special Technique in Black- and Red-figure Vase-painting", in The Colors of Clay: Special Techniques in Athenian Vases, Getty Publications, 2006, ISBN 9780892369423, pp. 178–179;

- ^ Savignoni L. 1899. "On Representations of Helios and of Selene." The Journal of Hellenic Studies 19: pp. 270–271

- ^ Zschietzschmann, W, Hellas and Rome: The Classical World in Pictures, Kessinger Publishing, 2006. ISBN 9781428655447. p.23

- ^ British Museum 1923,0401.199; LIMC Selene, Luna 21 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Selene, Luna 4 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Mithras 113 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Selene, Luna 15 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Selene, Luna 34 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Selene, Luna 2 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Selene, Luna 7 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Selene, Luna 9 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Selene, Luna 10 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; LIMC Selene, Luna 19 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. For the close association between the crescent moon and horns see Cashford.

- ^ Selene and Luna on Roman Coins (forumancientcoins.com): "Bronze coin of Caracalla from Nicopolis ad Istrum with a single star in the arms of the crescent moon; coin of Geta showing five stars; a denarius of Septimius Severus with an array of seven stars." Roman-era coins from Carrhae (Harran): Carrhae, Mesopotamia, modern day Harran (wildwinds.com)

- ^ Michael Alram, Nomina Propria Iranica in Nummis, Materialgrundlagen zu den iranischen Personennamen auf Antiken Münzen (1986); C. Augé, "Quelques monnaies d'Elymaïde," Bulletin de la Société Française de Numismatique, November 1976; N. Renaud, "Un nouveau souverain d'Elymaïde," Bulletin de la Société Française de Numismatique, January 1999, pp. 1–5. Coins of Elymais (parthia.com).

- ^ "A rare type with crescent and star alone on the reverse is probably Chashtana's earliest issue, struck before he extended his power into Malwa." H.H. Dodwell (Ed.), The Cambridge Shorter History of India, Cambridge University Press, 1935, p. 83.

- ^ Achaemenid period: "not normally associated with scenes cut in the Court Style"; Persepolis seal PFS 71 (M. B. Garrison in Curtis and Simpson (eds.), The World of Achaemenid Persia: History, Art and Society in Iran and the Ancient Near East (2010), p. 354) PFS 9 (M. B. Garrison, Seals And The Elite At Persepolis; Some Observations On Early Achaemenid Persian Art (1991), p. 8). Parthian period: "[t]he Parthian king Mithradates I conquered Mesopotamia around 147 BC, and Susa in about 140 BC A later Parthian king, Orodes II (58–38 BC), issued coins at Susa and elsewhere which display a star and crescent on the obverse. The succeeding ruler, Phraates IV (38-3/2 BC), minted coins showing either a star alone or a star with crescent moon. In representing the star and crescent on their coins the Parthians thus adopted traditional symbols used in Mesopotamia and Elam more than two millennia before their own arrival in those parts." John Hansman, "The great gods of Elymais" in Acta Iranica, Encyclopédie Permanente Des Etudes Iraniennes, v.X, Papers in Honor of Professor Mary Boyce, Brill Archive, 1985, pp 229–232

- ^ "Sasani coins remained in circulation in Moslem countries up to the end of the first century (Hijra). This detailed description of Sasani crowns was presented because the motifs mentioned, particularly the star and crescent gradually changed into Islamic symbols and have often appeared in the decorative patterns of various periods of Islamic art. [...] The flags of many Islamic countries bear crescents and stars and are proof of this Sasani innovation." Habibollah Ayatollahi (trans. Shermin Haghshenās), The Book of Iran: The History of Iranian Art, Alhoda UK, 2003, pp 155–157

- ^ "when we come to examine the history of the crescent as a badge of Muhammadanism, we are confronted by the fact that it was not employed by the Arabs or any of the first peoples who embraced the faith of the prophet" "The truth is that the crescent was not identified with Islam until after the appearance of the Osmanli Turks, whilst on the other hand there is the clearest evidence that in the time of the Crusades, and long before, the crescent and star were a regular badge of Byzantium and the Byzantine Emperors, some of whom placed it on their coins." William Ridgeway, "The Origin of the Turkish Crescent", in The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 38 (Jul. – Dec. 1908), pp. 241–258 (p 241)

- ^ Babayarov, Gaybulla; Kubatin, Andrey (2013). "Byzantine Impact on the Iconography of Western Turkic Coinage". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 66 (1): 52. doi:10.1556/AOrient.66.2013.1.3. ISSN 0001-6446. JSTOR 43283250.

- ^ In the 12th century found on pennies of William the Lion (r. 1174–1195). William Till, An Essay on the Roman Denarius and English Silver Penny (1838), p. 73. E.g. "Rev: short cross with crescent and pellets in angles and +RAVLD[ ] legend for the moneyer Raul Derling at Berwick or Roxburgh mint" (timelineauctions.com). Seaby SE5025 "Rev. [+RAV]L ON ROC, short cross with crescents & pellets in quarters" (wildwinds.com Archived 16 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Bohemond III of Antioch (r. 1163–1201) "Obv. Helmeted head of king in chain-maille armor, crescent and star to sides" (ancientresource.com)

- ^ "Billon denier, struck c. late 1140s – 1164. + RA[M]VNDVS COMS, cross pattée, pellet in 1st and 2nd quarters / CIVI[TAS T]RIPOLIS, eight-rayed star with pellets above crescent. ref: CCS 6–8; Metcalf 509 (ancientresource.com).

- ^ "The earliest church in the Morea to include a saint holding a shield marked by the crescent and star may be St. John Chrysostom, which has been dated on the basis of style to ca. 1300 [...]" Angeliki E. Laiou, Roy P. Mottahedeh, The Crusades From the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World, Dumbarton Oaks, 2001, p 278

- ^ p. 21; adopted by Virgil Solis in his Wappenbüchlein (1555)

- ^ Sara L. Uckelman, An Ordinary of Siebmacher's Wappenbuch (ellipsis.cx) (2014)

- ^ Kolar-Dimitrijević, Mira (2014). Povijest novca u Hrvatskoj, 1527. − 1941 [History of money in Croatia, 1527 − 1941] (PDF) (in Croatian). p. 13. ISBN 978-953-8013-03-4. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ "Wien 1, Stephansdom, Mondschein". Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften (in German). Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Richard is depicted as seated between a crescent and a "Sun full radiant" in his second Great Seal of 1198. English heraldic tradition of the early modern period associates the star and crescent design with Richard, with his victory over Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus in 1192, and with the arms of Portsmouth (Francis Wise A Letter to Dr Mead Concerning Some Antiquities in Berkshire, 1738, p. 18). Heraldic tradition also attributes a star-and-crescent badge to Richard (Charles Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, 1909, p. 468).

- ^ Found in the 19th century at the site of the Biais commandery, in Saint-Père-en-Retz, Loire-Atlantique, France, now in the Musée Dobré in Nantes, inv. no. 303. Philippe Josserand, "Les Templiers en Bretagne au Moyen Âge : mythes et réalités", Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'Ouest 119.4 (2012), 7–33 (p.24).

- ^ In 15th-century Europe, it was widely assumed that the gypsies were Egyptians (hence the name gypsies), and several gypsy leaders are known to have styled themselves as "counts of lesser Egypt". Wilhelm Ferdinand Bischoff, Deutsch-Zigeunerisches Wörterbuch (1827), p.14

- ^ Mohd Elfie Nieshaem Juferi, "What Is The Significance Of The Crescent Moon In Islam?". bismikaallahuma.org. 12 October 2005. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ Pamela Berger, The Crescent on the Temple: The Dome of the Rock as Image of the Ancient Jewish Sanctuary (2012), p. 164f

- ^ a b İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Vol. 4. Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı. 1991. p. 298.

- ^ "It seems possible, though not certain, that after the conquest Mehmed took over the crescent and star as an emblem of sovereignty from the Byzantines. The half-moon alone on a blood red flag, allegedly conferred on the Janissaries by Emir Orhan, was much older, as is demonstrated by numerous references to it dating from before 1453. But since these flags lack the star, which along with the half-moon is to be found on Sassanid and Byzantine municipal coins, it may be regarded as an innovation of Mehmed. It seems certain that in the interior of Asia tribes of Turkish nomads had been using the half-moon alone as an emblem for some time past, but it is equally certain that crescent and star together are attested only for a much later period. There is good reason to believe that old Turkish and Byzantine traditions were combined in the emblem of Ottoman and, much later, present-day Republican Turkish sovereignty." Franz Babinger (William C. Hickman Ed., Ralph Manheim Trans.), Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time, Princeton University Press, 1992, p 108

- ^ e.g. A. Locher, "With Star and Crescent: A Full and Authentic Account of a Recent Journey with a Caravan from Bombay to Constantinople"; Andrew Haggard, "Under Crescent and Star" (1895).

- ^ "Mosque and minaret are surmounted by crescents; the air glowing over the Golden Horn is, as it were, full of moons." Hezekiah Butterworth, Zigzag journeys in the Orient vol. 3 (1882), p. 481.

- ^ The symbolism of the star and crescent in the flag of the Kingdom of Libya (1951–1969) was explained in an English language booklet, The Libyan Flag & The National Anthem, issued by the Ministry of Information and Guidance of the Kingdom of Libya (year unknown, cited after Jos Poels at FOTW, 1997) as follows: "The crescent is symbolic of the beginning of the lunar month according to the Muslim calendar. It brings back to our minds the story of Hijra (migration) of our Prophet Mohammed from his home in order to spread Islam and teach the principles of right and virtue. The Star represents our smiling hope, the beauty of aim and object and the light of our belief in God, in our country, its dignity and honour which illuminate our way and puts an end to darkness."

- ^ Edward E. Curtis, Black Muslim religion in the Nation of Islam, 1960–1975 (2006), p. 157.

- ^ Joshua Lipes; Jilil Kashgary (4 April 2017). "Xinjiang Police Search Uyghur Homes For 'Illegal Items'". Radio Free Asia. Translated by Mamatjan Juma. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

A second announcement, issued Feb. 28 by the Chira (Cele) county government, said those who report individuals for having "stitched the 'star and crescent moon' insignia on their clothing or personal items" or the words "East Turkestan"—referring to the name of a short-lived Uyghur republic—on their mobile phone case, purse or other jewelry, were also eligible for cash payments.

- ^ The blazon of the coat of arms is attested in the 19th century, as Azure a crescent or, surmounted by an estoile of eight points of the last (William Berry, Robert Glover, Encyclopædia Heraldica, 1828). This is apparently based on minor seals used by Portsmouth mayors in the 18th century (Robert East H. Lewis, Extracts from Records in the Possession of the Municipal Corporation of the Borough of Portsmouth and from Other Documents Relating Thereto, 1891, p. 656). The medieval seal showed no such design (Henry Press Wright, The Story of the 'Domus Dei' of Portsmouth: Commonly Called the Royal Garrison Church, 1873, p. 12). The claim connecting the star and crescent design to the Great Seal of Richard I originates in the mid 20th century (Valentine Dyall, Unsolved Mysteries: A Collection of Weird Problems from the Past, 1954, p. 14).

- ^ a b c Peter Ziegler (ed.), Die Gemeindewappen des Kantons Zürich (1977), 74–77.

- Charles Boutell, "Device of Star (or Sun) and Crescent". In The Gentleman's Magazine, Volume XXXVI (New Series). London: John Nicols & Son, London, 1851, pp. 514–515

External links

[edit] Media related to Star and crescent at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Star and crescent at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of ☪ at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of ☪ at Wiktionary

![A star and crescent symbol with the star shown in a sixteen-rayed "sunburst" design (3rd century BC) on the Ai-Khanoum plaque.[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/AiKhanoumPlateSharp.jpg/250px-AiKhanoumPlateSharp.jpg)

![Coin of Mithradates VI Eupator. The obverse side has the inscription ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΙΘΡΑΔΑΤΟΥ ΕΥΠΑΤΟΡΟΣ with a stag feeding, with the star and crescent and monogram of Pergamum placed near the stag's head, all in an ivy-wreath.[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/CoinOfMithVI.jpg/330px-CoinOfMithVI.jpg)

![Great Seal of Richard I of England (1198)[46]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Seal_of_Richard_I_of_England.webp/120px-Seal_of_Richard_I_of_England.webp.png)

![Templar seal of the 13th century, probably of the preceptor of the commanderies at Coudrie and Biais (Brittany).[47]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/Frater_Robert_seal_templar.png/120px-Frater_Robert_seal_templar.png)

![Coat of arms of John Freigraf of "Lesser Egypt" (i.e. Romani/gypsy),[48] 18th-century drawing of a 1498 coat of arms in Pforzheim church.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Wappenbild_freigrafen_1448.jpg/120px-Wappenbild_freigrafen_1448.jpg)

![Flag of Portsmouth, England (18th century): crescent and estoile (with eight wavy rays).[58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/City_Flag_of_Portsmouth.svg/120px-City_Flag_of_Portsmouth.svg.png)

![Coat of arms of Niederglatt, Switzerland (1928)[59]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Niederglatt-blazon.svg/120px-Niederglatt-blazon.svg.png)

![Coat of arms of Oberglatt, Switzerland (1928)[59]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/04/Oberglatt-blazon.svg/120px-Oberglatt-blazon.svg.png)

![Coat of arms of Niederweningen, Switzerland (1928)[59]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Niederweningen-blazon.svg/120px-Niederweningen-blazon.svg.png)