Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

European single market

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

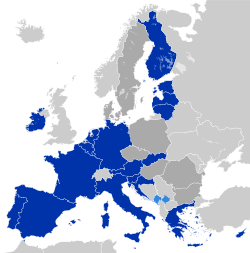

The European single market, also known as the European internal market or the European common market, is the single market comprising mainly the 27 member states of the European Union (EU). With certain exceptions, it also comprises Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway (through the Agreement on the European Economic Area), and Switzerland (through sectoral treaties). The single market seeks to guarantee the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people, known collectively as the "four freedoms".[2][3][4][5] This is achieved through common rules and standards that all participating states are legally committed to follow.

Any potential EU accession candidates are required to make association agreements with the EU during the negotiation, which must be implemented prior to accession.[6] In addition, through three individual agreements on a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with the EU, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine have also been granted limited access to the single market in selected sectors.[7] Turkey has access to the free movement of some goods via its membership in the European Union–Turkey Customs Union.[8] The United Kingdom left the European single market on 31 December 2020. An agreement was reached between the UK Government and European Commission to align Northern Ireland on rules for goods with the European single market, to maintain an open border on the island of Ireland.[9]

The market is intended to increase competition, labour specialisation, and economies of scale, allowing goods and factors of production to move to the area where they are most valued, thus improving the efficiency of the allocation of resources. It is also intended to drive economic integration whereby the once separate economies of the member states become integrated within a single EU-wide economy.[10] The creation of the internal market as a seamless, single market – which the Commission consider to be "one of the European Union's most significant achievements"[11] – is also an ongoing process, with the integration of the service industry still containing gaps.[12] According to a 2019 estimate, because of the single market the GDP of member countries is on average 9 percent higher than it would be if tariff and non-tariff restrictions were in place.[13]

History

[edit]One of the core objectives of the European Economic Community (EEC) upon its establishment in 1957 was the development of a common market offering free movement of goods, service, people and capital. Free movement of goods was established in principle through the customs union between its then-six member states.

However, the EEC struggled to enforce a single market due to the absence of strong decision-making structures. Because of protectionist attitudes, it was difficult to replace intangible barriers with mutually recognized standards and common regulations.

In the 1980s, when the economy of the EEC began to lag behind the rest of the developed world, Margaret Thatcher sent Lord Cockfield to the Delors Commission to take the initiative to attempt to relaunch the common market. Cockfield wrote and published a White Paper in 1985 identifying 300 measures to be addressed in order to complete a single market.[14][15][16] The White Paper was well received and led to the adoption of the Single European Act, a treaty which reformed the decision-making mechanisms of the EEC and set a deadline of 31 December 1992 for the completion of a single market. In the end, it was launched on 1 January 1993.[17]

The new approach, pioneered at the Delors Commission, combined positive and negative integration, relying upon minimum rather than exhaustive harmonisation. Negative integration consists of prohibitions imposed on member states banning discriminatory behaviour and other restrictive practices. Positive integration consists of approximating laws and standards. Especially important (and controversial) in this respect is the adoption of harmonising legislation under Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

The commission also relied upon the European Court of Justice's Cassis de Dijon[18] jurisprudence, under which member states were obliged to recognise goods which had been legally produced in another member state, unless the member state could justify the restriction by reference to a mandatory requirement. Harmonisation would only be used to overcome barriers created by trade restrictions which survived the Cassis mandatory requirements test, and to ensure essential standards where there was a risk of a race to the bottom. Thus, harmonisation was largely used to ensure basic health and safety standards were met.

By 1992 about 90% of the issues had been resolved[19] and in the same year the Maastricht Treaty set about to create an Economic and Monetary Union as the next stage of integration. Work on freedom for services took longer, and was the last freedom to be implemented, mainly through the Posting of Workers Directive (adopted in 1996)[20] and the Directive on services in the internal market (adopted in 2006).[21]

In 1997 the Amsterdam Treaty abolished physical barriers across the internal market by incorporating the Schengen Area within the competences of the EU. The Schengen Agreement implements the abolition of border controls between most member states, common rules on visas, and police and judicial co-operation.[22]

The official goal of the Lisbon Treaty was to establish an internal market, which would balance economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy, aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment, with also promoting scientific and technological advance.[a] Even as the Lisbon Treaty came into force in 2009, however, some areas pertaining to parts of the four freedoms (especially in the field of services) had not yet been completely opened. Those, along with further work on the economic and monetary union, would see the EU move further to a European Home Market.[19]

In 2010, José Manuel Durão Barroso, then President of the European Commission, asked former Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti to draft a report on revitalizing the European Single Market. The resulting document, known as the Monti Report, was presented in May 2010 and identified barriers to the internal market while proposing measures to strengthen economic integration and competitiveness. The report laid the groundwork for the "Single Market Act",[b] a set of initiatives launched by the European Commission to enhance the functioning of the Single Market.[24]

Following the Monti Report, the European Union continued to commission high-level reflections on the future of its economic integration. Priority actions identified by "Single Market Act II" in October 2012 included actions in the fields of transport, citizen and business mobility, the digital economy and social entrepreneurship.[25]

In April 2024, Enrico Letta, former Italian Prime Minister and President of the Jacques Delors Institute, presented the Letta Report, Much More Than a Market, which called for a strategic renewal of the European Single Market to support the green and digital transitions, enhance economic cohesion, and promote a "fifth freedom" focused on knowledge and innovation.[26][27] Around the same time, Mario Draghi was tasked with preparing a report on European competitiveness, addressing long-term structural reforms needed to boost productivity, resilience, and the EU's global economic standing.[28]

Four freedoms

[edit]The "four freedoms" of the single market are:

- Free movement of goods

- Free movement of capital

- Freedom to establish and provide services

- Free movement of labour.

Goods

[edit]The range of "goods" (or "products") covered by the term "free movement of goods" "is as wide as the range of goods in existence".[29] Goods are only covered if they have economic value, i.e. they can be valued in money and are capable of forming the subject of commercial transactions. Works of art, coins which are no longer in circulation and water are noted as examples of "goods".[29] Fish are goods, but a European Court of Justice ruling in 1999 stated that fishing rights (or fishing permits) are not goods, but a provision of service. The ruling further explains that, both capital and service can be valued in money and are capable of forming the subject of commercial transactions, but they are not goods.[30]

Council Regulation (EC) 2679/98 of 7 December 1998, on the functioning of the internal market in relation to the free movement of goods among the Member States, was aimed at preventing obstacles to the free movement of goods attributable to "action or inaction" by a Member State. The regulation empowered the Commission to request intervention by a Member State when the actions of private individuals were creating an "obstacle" to free movement of goods. A resolution was adopted by the Council and member state government representatives on the same day, under which the member states agreed to take action where necessary to protect the free movement of goods and other freedoms, and to issue public information where there were disruptions, including their efforts to address obstacles to free movement of goods.[31]

Customs duties and taxation

[edit]The customs union of the European Union removes customs barriers between member states and operates a common customs policy towards third countries, with the aim "to ensure normal conditions of competition and to remove all restrictions of a fiscal nature capable of hindering the free movement of goods within the Common Market".[32]

Aspects of the EU Customs area extend to a number of non-EU-member states, namely Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and Turkey, under separately negotiated arrangements. The United Kingdom agreed on a trade deal with the European Union on 24 December 2020, which was signed by Prime Minister Boris Johnson on 30 December 2020.[33]

Customs duties

[edit]Article 30 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ("TFEU") prohibits border levies between member states on both European Union Customs Union produce and non-EUCU (third-country) produce. Under Article 29 of the TFEU, customs duty applicable to third country products are levied at the point of entry into EUCU, and once within the EU external border goods may circulate freely between member states.[35]

Under the operation of the Single European Act, customs border controls between member states have been largely abandoned. Physical inspections on imports and exports have been replaced mainly by audit controls and risk analysis.[citation needed]

Charges having equivalent effect to customs duties

[edit]Article 30 of the TFEU prohibits not only customs duties but also charges having equivalent effect. The European Court of Justice defined "charge having equivalent effect" in Commission v Italy.

[A]ny pecuniary charge, however small and whatever its designation and mode of application, which is imposed unilaterally on domestic or foreign goods by reason of the fact that they cross a frontier, and which is not a customs duty in the strict sense, constitutes a charge having an equivalent effect... even if it is not imposed for the benefit of the state, is not discriminatory or protective in effect and if the product on which the charge is imposed is not in competition with any domestic product.[36]

A charge is a customs duty if it is proportionate to the value of the goods; if it is proportionate to the quantity, it is a charge having equivalent effect to a customs duty.[37]

There are three exceptions to the prohibition on charges imposed when goods cross a border, listed in Case 18/87 Commission v Germany. A charge is not a customs duty or charge having equivalent effect if:

- it relates to a general system of internal dues applied systematically and in accordance with the same criteria to domestic products and imported products alike,[38]

- if it constitutes payment for a service in fact rendered to the economic operator of a sum in proportion to the service,[39] or

- subject to certain conditions, if it attaches to inspections carried out to fulfil obligations imposed by Union law.[40]

Taxation

[edit]Article 110 of the TFEU provides:

No Member State shall impose, directly or indirectly, on the products of other member states any internal taxation of any kind in excess of that imposed directly or indirectly on similar domestic products.

Furthermore, no Member State shall impose on the products of other member states any internal taxation of such a nature as to afford indirect protection to other products.

In the taxation of rum case, the ECJ stated that:

The Court has consistently held that the purpose of Article 90 EC [now Article 110], as a whole, is to ensure the free movement of goods between the member states under normal conditions of competition, by eliminating all forms of protection which might result from the application of discriminatory internal taxation against products from other member states, and to guarantee absolute neutrality of internal taxation as regards competition between domestic and imported products.[41]

Quantitative and equivalent restrictions

[edit]Free movement of goods within the European Union is achieved by a customs union and the principle of non-discrimination.[42] The EU manages imports from non-member states, duties between member states are prohibited, and imports circulate freely.[43] In addition under the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union article 34, 'Quantitative restrictions on imports and all measures having equivalent effect shall be prohibited between Member States'. In Procureur du Roi v Dassonville[44] the Court of Justice held that this rule meant all "trading rules" that are "enacted by Member States" which could hinder trade "directly or indirectly, actually or potentially" would be caught by article 34.[45] This meant that a Belgian law requiring Scotch whisky imports to have a certificate of origin was unlikely to be lawful. It discriminated against parallel importers like Mr Dassonville, who could not get certificates from authorities in France, where they bought the Scotch. This "wide test",[46] to determine what could potentially be an unlawful restriction on trade, applies equally to actions by quasi-government bodies, such as the former "Buy Irish" company that had government appointees.[47]

It also means states can be responsible for private actors. For instance, in Commission v France French farmer vigilantes were continually sabotaging shipments of Spanish strawberries, and even Belgian tomato imports. France was liable for these hindrances to trade because the authorities "manifestly and persistently abstained" from preventing the sabotage.[48] Generally speaking, if a member state has laws or practices that directly discriminate against imports (or exports under TFEU article 35) then it must be justified under article 36, which outlines all of the justifiable instances.[49] The justifications include public morality, policy or security, "protection of health and life of humans, animals or plants", "national treasures" of "artistic, historic or archaeological value" and "industrial and commercial property". In addition, although not clearly listed, environmental protection can justify restrictions on trade as an over-riding requirement derived from TFEU article 11.[50] The Eyssen v Netherlands case from 1981 outlined a disagreement between the science community and the Dutch government whether niacin in cheese posed a public risk. As public risk falls under article 36, meaning that a quantitative restriction can be imposed, it justified the import restriction against the Eyssen cheese company by the Dutch government.[51]

More generally, it has been increasingly acknowledged that fundamental human rights should take priority over all trade rules. So, in Schmidberger v Austria[52] the Court of Justice held that Austria did not infringe article 34 by failing to ban a protest that blocked heavy traffic passing over the A13, Brenner Autobahn, en route to Italy. Although many companies, including Mr Schmidberger's German undertaking, were prevented from trading, the Court of Justice reasoned that freedom of association is one of the "fundamental pillars of a democratic society", against which the free movement of goods had to be balanced,[53] and was probably subordinate. If a member state does appeal to the article 36 justification, the measures it takes have to be applied proportionately. This means the rule must be pursue a legitimate aim and (1) be suitable to achieve the aim, (2) be necessary, so that a less restrictive measure could not achieve the same result, and (3) be reasonable in balancing the interests of free trade with interests in article 36.[54]

Often rules apply to all goods neutrally, but may have a greater practical effect on imports than domestic products. For such "indirect" discriminatory (or "indistinctly applicable") measures the Court of Justice has developed more justifications: either those in article 36, or additional "mandatory" or "overriding" requirements such as consumer protection, improving labour standards,[56] protecting the environment,[57] press diversity,[58] fairness in commerce,[59] and more: the categories are not closed.[60] In the most famous case Rewe-Zentral AG v Bundesmonopol für Branntwein,[61] the Court of Justice found that a German law requiring all spirits and liqueurs (not just imported ones) to have a minimum alcohol content of 25 per cent was contrary to TFEU article 34, because it had a greater negative effect on imports. German liqueurs were over 25 per cent alcohol, but Cassis de Dijon, which Rewe-Zentrale AG wished to import from France, only had 15 to 20 per cent alcohol. The Court of Justice rejected the German government's arguments that the measure proportionately protected public health under TFEU article 36,[c] because stronger beverages were available and adequate labelling would be enough for consumers to understand what they bought.[62] This rule primarily applies to requirements about a product's content or packaging. In Walter Rau Lebensmittelwerke v De Smedt PVBA[63] the Court of Justice found that a Belgian law requiring all margarine to be in cube shaped packages infringed article 34, and was not justified by the pursuit of consumer protection. The argument that Belgians would believe it was butter if it was not cube shaped was disproportionate: it would "considerably exceed the requirements of the object in view" and labelling would protect consumers "just as effectively".[64]

In a 2003 case, Commission v Italy,[65] Italian law required that cocoa products that included other vegetable fats could not be labelled as "chocolate". It had to be "chocolate substitute". All Italian chocolate was made from cocoa butter alone, but British, Danish and Irish manufacturers used other vegetable fats. They claimed the law infringed article 34. The Court of Justice held that a low content of vegetable fat did not justify a "chocolate substitute" label. This was derogatory in the consumers' eyes. A "neutral and objective statement" was enough to protect consumers. If member states place considerable obstacles on the use of a product, this can also infringe article 34. So, in a 2009 case, Commission v Italy, the Court of Justice held that an Italian law prohibiting motorcycles or mopeds from pulling trailers infringed article 34.[66] Again, the law applied neutrally to everyone, but disproportionately affected importers, because Italian companies did not make trailers. This was not a product requirement, but the Court reasoned that the prohibition would deter people from buying it: it would have "a considerable influence on the behaviour of consumers" that "affects the access of that product to the market".[67] It would require justification under article 36, or as a mandatory requirement.

In contrast to product requirements or other laws that hinder market access, the Court of Justice developed a presumption that "selling arrangements" would be presumed to not fall into TFEU article 34, if they applied equally to all sellers, and affected them in the same manner in fact. In Keck and Mithouard[68] two importers claimed that their prosecution under a French competition law, which prevented them from selling Picon beer under wholesale price, was unlawful. The aim of the law was to prevent cut throat competition, not to hinder trade.[69] The Court of Justice held, as "in law and in fact" it was an equally applicable "selling arrangement" (not something that alters a product's content[70]) it was outside the scope of article 34, and so did not need to be justified. Selling arrangements can be held to have an unequal effect "in fact" particularly where traders from another member state are seeking to break into the market, but there are restrictions on advertising and marketing. In Konsumentombudsmannen v De Agostini[71] the Court of Justice reviewed Swedish bans on advertising to children under age 12, and misleading commercials for skin care products. While the bans have remained (justifiable under article 36 or as a mandatory requirement) the Court emphasised that complete marketing bans could be disproportionate if advertising were "the only effective form of promotion enabling [a trader] to penetrate" the market. In Konsumentombudsmannen v Gourmet AB[72] the Court suggested that a total ban for advertising alcohol on the radio, TV and in magazines could fall within article 34 where advertising was the only way for sellers to overcome consumers' "traditional social practices and to local habits and customs" to buy their products, but again the national courts would decide whether it was justified under article 36 to protect public health. Under the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, the EU harmonised restrictions on restrictions on marketing and advertising, to forbid conduct that distorts average consumer behaviour, is misleading or aggressive, and sets out a list of examples that count as unfair.[73] Increasingly, states have to give mutual recognition to each other's standards of regulation, while the EU has attempted to harmonise minimum ideals of best practice. The attempt to raise standards is hoped to avoid a regulatory "race to the bottom", while allowing consumers access to goods from around the continent.[citation needed]

Capital

[edit]Free movement of capital was traditionally seen as the fourth freedom, after goods, workers and persons, services and establishment. The original Treaty of Rome required that restrictions on free capital flows only be removed to the extent necessary for the common market. From the Maastricht Treaty, now in TFEU article 63, "all restrictions on the movement of capital between the Member States and between Member States and third countries shall be prohibited". This means capital controls of various kinds are prohibited, including limits on buying currency, limits on buying company shares or financial assets, or government approval requirements for foreign investment. By contrast, taxation of capital, including corporate tax, capital gains tax and financial transaction tax, are not affected so long as they do not discriminate by nationality. According to the Capital Movement Directive 1988, Annex I, 13 categories of capital which must move free are covered.[74]

In Baars v Inspecteur der Belastingen Particulieren the Court of Justice held that for investments in companies, the capital rules, rather than freedom of establishment rules, were engaged if an investment did not enable a "definite influence" through shareholder voting or other rights by the investor.[75] That case held a Dutch Wealth Tax Act 1964 unjustifiably exempted Dutch investments, but not Mr Baars' investments in an Irish company, from the tax: the wealth tax, or exemptions, had to be applied equally. On the other hand, TFEU article 65(1) does not prevent taxes that distinguish taxpayers based on their residence or the location of an investment (as taxes commonly focus on a person's actual source of profit) or any measures to prevent tax evasion.[76] Apart from tax cases, largely following from the opinions of Advocate General Maduro,[77] a series of cases held that government owned golden shares were unlawful. In Commission v Germany the Commission claimed the German Volkswagen Act 1960 violated article 63, in that §2(1) restricted any party having voting rights exceeding 20% of the company, and §4(3) allowed a minority of 20% of shares held by the Lower Saxony government to block any decisions. Although this was not an impediment to the actual purchase of shares, or receipt of dividends by any shareholder, the Court of Justice's Grand Chamber agreed that it was disproportionate for the government's stated aim of protecting workers or minority shareholders.[78] Similarly, in Commission v Portugal the Court of Justice held that Portugal infringed free movement of capital by retaining golden shares in Portugal Telecom that enabled disproportionate voting rights, by creating a "deterrent effect on portfolio investments" and reducing "the attractiveness of an investment".[79] This suggested the Court's preference that a government, if it sought public ownership or control, should nationalise in full the desired proportion of a company in line with TFEU article 345.[80]

Capital within the EU may be transferred in any amount from one country to another (except that Greece currently[when?] has capital controls restricting outflows, and Cyprus imposed capital controls between 2013 and April 2015). All intra-EU transfers in euro are considered as domestic payments and bear the corresponding domestic transfer costs.[81] This includes all member States of the EU, even those outside the eurozone providing the transactions are carried out in euro.[82] Credit/debit card charging and ATM withdrawals within the Eurozone are also charged as domestic; however, paper-based payment orders, like cheques, have not been standardised so these are still domestic-based. The ECB has also set up a clearing system, T2 since March 2023, for large euro transactions.[83]

The final stage of completely free movement of capital was thought to require a single currency and monetary policy, eliminating the transaction costs and fluctuations of currency exchange. Following a Report of the Delors Commission in 1988,[84] the Maastricht Treaty made economic and monetary union an objective, first by completing the internal market, second by creating a European System of Central Banks to co-ordinate common monetary policy, and third by locking exchange rates and introducing a single currency, the euro. Today, 20 member states have adopted the euro, one is in the process of adopting (Bulgaria), one has determined to opt-out (Denmark) and 5 member states have delayed their accession, particularly since the Eurozone crisis. According to TFEU articles 119 and 127, the objective of the European Central Bank and other central banks ought to be price stability. This has been criticised for apparently being superior to the objective of full employment in the Treaty on European Union article 3.[85]

Within the building on the Investment Plan for Europe, for a closer integration of capital markets, in 2015, the Commission adopted the Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union (CMU) setting out a list of key measures to achieve a true single market for capital in Europe, which deepens the existing Banking Union, because this revolves around disintermediated, market-based forms of financing, which should represent an alternative to the traditionally predominant (in Europe) bank-based financing channel.[86] The EU's political and economic context call for strong and competitive capital markets to finance the EU economy.[87] The CMU project is a political signal to strengthen the single market as a project of all 28 Member States,[88] instead of just the Eurozone countries, and sent a strong signal to the UK to remain an active part of the EU, before Brexit.[89]

Services

[edit]As well as creating rights for "workers" who generally lack bargaining power in the market,[90] the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union or TFEU also protects the "freedom of establishment" in article 49, and "freedom to provide services" in article 56.[91]

Establishment

[edit]In Gebhard v Consiglio dell’Ordine degli Avvocati e Procuratori di Milano[92] the Court of Justice held that to be "established" means to participate in economic life "on a stable and continuous basis", while providing "services" meant pursuing activity more "on a temporary basis". This meant that a lawyer from Stuttgart, who had set up chambers in Milan and was censured by the Milan Bar Council for not having registered, should claim for breach of establishment freedom, rather than service freedom. However, the requirements to be registered in Milan before being able to practice would be allowed if they were non-discriminatory, "justified by imperative requirements in the general interest" and proportionately applied.[93] All people or entities that engage in economic activity, particularly the self-employed, or "undertakings" such as companies or firms, have a right to set up an enterprise without unjustified restrictions.[94] The Court of Justice has held that both a member state government and a private party can hinder freedom of establishment,[95] so article 49 has both "vertical" and "horizontal" direct effect. In Reyners v Belgium[96] the Court of Justice held that a refusal to admit a lawyer to the Belgian bar because he lacked Belgian nationality was unjustified. TFEU article 49 says states are exempt from infringing others' freedom of establishment when they exercise "official authority", but this did an advocate's work[clarification needed] (as opposed to a court's) was not official.[97] By contrast in Commission v Italy the Court of Justice held that a requirement for lawyers in Italy to comply with maximum tariffs unless there was an agreement with a client was not a restriction.[98] The Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice held the commission had not proven that this had any object or effect of limiting practitioners from entering the market.[99] Therefore, there was no prima facie infringement freedom of establishment that needed to be justified.[citation needed]

In regard to companies, the Court of Justice held in R (Daily Mail and General Trust plc) v HM Treasury that member states could restrict a company moving its seat of business, without infringing TFEU article 49.[102] This meant the Daily Mail newspaper's parent company could not avoid tax by shifting its residence to the Netherlands without first settling its tax bills in the UK. The UK did not need to justify its action, as rules on company seats were not yet harmonised. By contrast, in Centros Ltd v Erhvervs- og Selkabssyrelsen the Court of Justice found that a UK limited company operating in Denmark could not be required to comply with Denmark's minimum share capital rules. UK law only required £1 of capital to start a company, while Denmark's legislature took the view companies should only be started up if they had 200,000 Danish krone (around €27,000) to protect creditors if the company failed and went insolvent. The Court of Justice held that Denmark's minimum capital law infringed Centros Ltd's freedom of establishment and could not be justified, because a company in the UK could admittedly provide services in Denmark without being established there, and there were less restrictive means of achieving the aim of creditor protection.[103] This approach was criticised as potentially opening the EU to unjustified regulatory competition, and a race to the bottom in standards, like in the US where the state of Delaware attracts most companies and is often argued to have the worst standards of accountability of boards, and low corporate taxes as a result.[104] Similarly in Überseering BV v Nordic Construction GmbH the Court of Justice held that a German court could not deny a Dutch building company the right to enforce a contract in Germany on the basis that it was not validly incorporated in Germany. Although restrictions on freedom of establishment could be justified by creditor protection, labour rights to participate in work, or the public interest in collecting taxes, denial of capacity went too far: it was an "outright negation" of the right of establishment.[105] However, in Cartesio Oktató és Szolgáltató bt the Court of Justice affirmed again that because corporations are created by law, they are in principle subject to any rules for formation that a state of incorporation wishes to impose. This meant that the Hungarian authorities could prevent a company from shifting its central administration to Italy while it still operated and was incorporated in Hungary.[106] Thus, the court draws a distinction between the right of establishment for foreign companies (where restrictions must be justified), and the right of the state to determine conditions for companies incorporated in its territory,[107] although it is not entirely clear why.[108]

Types of service

[edit]The "freedom to provide services" under TFEU article 56 applies to people who provide services "for remuneration", especially in commercial or professional activity.[109] For example, in Van Binsbergen v Bestuur van de Bedrijfvereniging voor de Metaalnijverheid a Dutch lawyer moved to Belgium while advising a client in a social security case, and was told he could not continue because Dutch law said only people established in the Netherlands could give legal advice.[110] The Court of Justice held that the freedom to provide services applied, it was directly effective, and the rule was probably unjustified: having an address in the member state would be enough to pursue the legitimate aim of good administration of justice.[111]

Case law states that the treaty provisions relating to the freedom to provide services do not apply in situations where the service, service provider and other relevant facts are confined within a single member state.[112] An early Council Directive from 26 July 1971 included works contracts within the scope of services, and provided for the abolition of restrictions on the freedom to provide services in respect of public works contracts.[113]

The Court of Justice has held that secondary education falls outside the scope of article 56,[114] because usually the state funds it, though higher education does not.[115] Health care generally counts as a service. In Geraets-Smits v Stichting Ziekenfonds[116] Mrs Geraets-Smits claimed she should be reimbursed by Dutch social insurance for the costs of receiving treatment in Germany. The Dutch health authorities regarded the treatment as unnecessary, so she argued this restricted the freedom (of the German health clinic) to provide services. Several governments submitted that hospital services should not be regarded as economic, and should not fall within article 56. But the Court of Justice held that health care was a "service" even though the government (rather than the service recipient) paid for the service.[117] National authorities could be justified in refusing to reimburse patients for medical services abroad if the health care received at home was without undue delay, and it followed "international medical science" on which treatments counted as normal and necessary.[118] The Court requires that the individual circumstances of a patient justify waiting lists, and this is also true in the context of the UK's National Health Service.[119] Aside from public services, another sensitive field of services are those classified as illegal. Josemans v Burgemeester van Maastricht held that the Netherlands' regulation of cannabis consumption, including the prohibitions by some municipalities on tourists (but not Dutch nationals) going to coffee shops,[120] fell outside article 56 altogether. The Court of Justice reasoned that narcotic drugs were controlled in all member states, and so this differed from other cases where prostitution or other quasi-legal activity was subject to restriction.

If an activity does fall within article 56, a restriction can be justified under article 52 or over-riding requirements developed by the Court of Justice. In Alpine Investments BV v Minister van Financiën[121] a business that sold commodities futures (with Merrill Lynch and another banking firm) attempted to challenge a Dutch law prohibiting cold calling customers. The Court of Justice held the Dutch prohibition pursued a legitimate aim to prevent "undesirable developments in securities trading" including protecting the consumer from aggressive sales tactics, thus maintaining confidence in the Dutch markets. In Omega Spielhallen GmbH v Bonn,[122] a "laserdrome" business was banned by the Bonn council. It bought fake laser gun services from a UK firm called Pulsar Ltd, but residents had protested against "playing at killing" entertainment. The Court of Justice held that the German constitutional value of human dignity, which underpinned the ban, did count as a justified restriction on the freedom to provide services. In Liga Portuguesa de Futebol v Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Lisboa the Court of Justice also held that the state monopoly on gambling, and a penalty for a Gibraltar firm that had sold internet gambling services, was justified to prevent fraud and gambling where people's views were highly divergent.[123] The ban was proportionate as this was an appropriate and necessary way to tackle the serious problems of fraud that arise over the internet. In the Services Directive[124] a group of justifications were codified in article 16 that the case law has developed.

Digital Single Market

[edit]

In May 2015 the Juncker Commission[125] announced a plan to reverse the fragmentation of internet shopping and other online services by establishing a Single Digital Market that would cover digital services and goods from e-commerce to parcel delivery rates, uniform telecoms and copyright rules.[126]

People

[edit]The free movement of people means EU citizens can move freely between member states for whatever reason (or without any reason) and may reside in any member state they choose if they are not an undue burden on the social welfare system or public safety in their chosen member state.[127] This required reduction of administrative formalities and greater recognition of professional qualifications of other states.[128] Fostering the free movement of people has been a major goal of European integration since the 1950s.[129]

Broadly defined, this freedom enables citizens of one Member State to travel to another, to reside and to work there (permanently or temporarily). The idea behind EU legislation in this field is that citizens from other member states should be treated equally to domestic citizens and should not be discriminated against.[citation needed]

The main provision on the freedom of movement of persons is Article 45 of the TFEU, which prohibits restrictions on the basis of nationality.[citation needed]

Free movement of workers

[edit]Since its foundation, the Treaties sought to enable people to pursue their life goals in any country through free movement.[130] Reflecting the economic nature of the project, the European Community originally focused upon free movement of workers: as a "factor of production".[131] However, from the 1970s, this focus shifted towards developing a more "social" Europe.[132] Free movement was increasingly based on "citizenship", so that people had rights to empower them to become economically and socially active, rather than economic activity being a precondition for rights. This means the basic "worker" rights in TFEU article 45 function as a specific expression of the general rights of citizens in TFEU articles 18 to 21. According to the Court of Justice, a "worker" is anybody who is economically active, which includes everyone in an employment relationship, "under the direction of another person" for "remuneration".[133] A job, however, need not be paid in money for someone to be protected as a worker. For example, in Steymann v Staatssecretaris van Justitie, a German man claimed the right to residence in the Netherlands, while he volunteered plumbing and household duties in the Bhagwan community, which provided for everyone's material needs irrespective of their contributions.[134] The Court of Justice held that Mr Steymann was entitled to stay, so long as there was at least an "indirect quid pro quo" for the work he did. Having "worker" status means protection against all forms of discrimination by governments, and employers, in access to employment, tax, and social security rights. By contrast a citizen, who is "any person having the nationality of a Member State" (TFEU article 20(1)), has rights to seek work, vote in local and European elections, but more restricted rights to claim social security.[135] In practice, free movement has become politically contentious as nationalist political parties appear to have utilised concerns about immigrants taking jobs and benefits.

The Free Movement of Workers Regulation articles 1 to 7 set out the main provisions on equal treatment of workers. First, articles 1 to 4 generally require that workers can take up employment, conclude contracts, and not suffer discrimination compared to nationals of the member state.[137] In a famous case, the Belgian Football Association v Bosman, a Belgian footballer named Jean-Marc Bosman claimed that he should be able to transfer from R.F.C. de Liège to USL Dunkerque when his contract finished, regardless of whether Dunkerque could afford to pay Liège the habitual transfer fees.[138] The Court of Justice held "the transfer rules constitute[d] an obstacle to free movement" and were unlawful unless they could be justified in the public interest, but this was unlikely. In Groener v Minister for Education[139] the Court of Justice accepted that a requirement to speak Gaelic to teach in a Dublin design college could be justified as part of the public policy of promoting the Irish language, but only if the measure was not disproportionate. By contrast in Angonese v Cassa di Risparmio di Bolzano SpA[140] a bank in Bolzano, Italy, was not allowed to require Mr Angonese to have a bilingual certificate that could only be obtained in Bolzano. The Court of Justice, giving "horizontal" direct effect to TFEU article 45, reasoned that people from other countries would have little chance of acquiring the certificate, and because it was "impossible to submit proof of the required linguistic knowledge by any other means", the measure was disproportionate. Second, article 7(2) requires equal treatment in respect of tax. In Finanzamt Köln Altstadt v Schumacker[141] the Court of Justice held that it contravened TFEU art 45 to deny tax benefits (e.g. for married couples, and social insurance expense deductions) to a man who worked in Germany, but was resident in Belgium when other German residents got the benefits. By contrast in Weigel v Finanzlandesdirektion für Vorarlberg the Court of Justice rejected Mr Weigel's claim that a re-registration charge upon bringing his car to Austria violated his right to free movement. Although the tax was "likely to have a negative bearing on the decision of migrant workers to exercise their right to freedom of movement", because the charge applied equally to Austrians, in absence of EU legislation on the matter it had to be regarded as justified.[142] Third, people must receive equal treatment regarding "social advantages", although the Court has approved residential qualifying periods. In Hendrix v Employee Insurance Institute the Court of Justice held that a Dutch national was not entitled to continue receiving incapacity benefits when he moved to Belgium, because the benefit was "closely linked to the socio-economic situation" of the Netherlands.[143] Conversely, in Geven v Land Nordrhein-Westfalen the Court of Justice held that a Dutch woman living in the Netherlands, but working between 3 and 14 hours a week in Germany, did not have a right to receive German child benefits,[144] even though the wife of a man who worked full-time in Germany but was resident in Austria could.[145] The general justifications for limiting free movement in TFEU article 45(3) are "public policy, public security or public health",[146] and there is also a general exception in article 45(4) for "employment in the public service".

For workers not citizens of the union but employed in one member state with a work permit, there is not the same freedom of movement within the Union. They need to apply for a new work permit if wanting to work in a different state. A facilitation mechanism for this process is the Van Der Elst visa which gives easier rules should a non-EU worker already in one EU state need to be sent to another, for the same employer, because of a service contract that the employer made with a customer in that other state.[citation needed]

Free movement of citizens

[edit]Beyond the right of free movement to work, the EU has increasingly sought to guarantee rights of citizens, and rights simply by being a human being.[147] But although the Court of Justice stated that 'Citizenship is destined to be the fundamental status of nationals of the Member States',[148] political debate remains on who should have access to public services and welfare systems funded by taxation.[149] In 2008, just 8 million people from 500 million EU citizens (1.7 per cent) had in fact exercised rights of free movement, the vast majority of them workers.[150] According to TFEU article 20, citizenship of the EU derives from nationality of a member state. Article 21 confers general rights to free movement in the EU and to reside freely within limits set by legislation. This applies for citizens and their immediate family members.[151] This triggers four main groups of rights: (1) to enter, depart and return, without undue restrictions, (2) to reside, without becoming an unreasonable burden on social assistance, (3) to vote in local and European elections, and (4) the right to equal treatment with nationals of the host state, but for social assistance only after 3 months of residence.

First, article 4 of the Citizens Rights Directive 2004 says every citizen has the right to depart a member state with a valid passport or national identity card. Article 5 gives every citizen a right of entry, subject to national border controls. Schengen Area countries (of which Ireland is not included) have abolished the need to show travel documents, and police searches at borders, altogether. These reflect the general principle of free movement in TFEU article 21. Second, article 6 allows every citizen to stay three months in another member state, whether economically active or not. Article 7 allows stays over three months with evidence of "sufficient resources... not to become a burden on the social assistance system". Articles 16 and 17 give a right to permanent residence after 5 years without conditions. Third, TEU article 10(3) requires the right to vote in the local constituencies for the European Parliament wherever a citizen lives.

Fourth, and more debated, article 24 requires that the longer an EU citizen stays in a host state, the more rights they have to access public and welfare services, on the basis of equal treatment. This reflects general principles of equal treatment and citizenship in TFEU articles 18 and 20. In a simple case, in Sala v Freistaat Bayern the Court of Justice held that a Spanish woman who had lived in (Germany) for 25 years and had a baby was entitled to child support, without the need for a residence permit, because Germans did not need one.[152] In Trojani v Centre public d’aide sociale de Bruxelles, a French man who lived in Belgium for two years was entitled to the "minimex" allowance from the state for a minimum living wage.[153] In Grzelczyk v Centre Public d’Aide Sociale d’Ottignes-Louvain-la-Neuve[154] a French student, who had lived in Belgium for three years, was entitled to receive the "minimex" income support for his fourth year of study. Similarly, in R (Bidar) v London Borough of Ealing the Court of Justice held that it was lawful to require a French UCL economics student to have lived in the UK for three years before receiving a student loan, but not that he had to have additional "settled status".[155] Similarly, in Commission v Austria, Austria was not entitled to restrict its university places to Austrian students to avoid "structural, staffing and financial problems" if (mainly German) foreign students applied, unless it proved there was an actual problem.[156] However, in Dano v Jobcenter Leipzig, the Court of Justice held that the German government was entitled to deny child support to a Romanian mother who had lived in Germany for 3 years, but had never worked. Because she lived in Germany for over 3 months, but under 5 years, she had to show evidence of "sufficient resources", since the Court reasoned the right to equal treatment in article 24 within that time depended on lawful residence under article 7.[157]

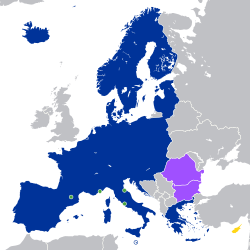

Schengen Area

[edit]Within the Schengen Area, 25 of the 27 EU member states (excluding Cyprus, and Ireland) and the four EFTA members (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland) have abolished physical barriers across the single market by eliminating border controls. In 2015, limited controls were temporarily re-imposed at some internal borders in response to the migrant crisis.

Public sector procurement of goods and services

[edit]Public procurement legislation [158] and guidance based on "a set of basic standards for the award of public contracts which are derived directly from the rules and principles of the EC Treaty",[159] relating to the four freedoms, require equal treatment, non-discrimination, mutual recognition, proportionality and transparency to be maintained when purchasing goods and services for EU public sector bodies.

Integration of non-EU states

[edit]

Only the EU member states are fully part of the European single market, while several other countries and territories have been granted various degrees of participation. The single market has been extended, with exceptions, to Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway through the agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA) and to Switzerland through sectoral bilateral and multilateral agreements. The exceptions, where these EFTA states are not bound by EU law, are:[160]

- the common agricultural policy and the common fisheries policy (although the EEA agreement contains provisions on trade in agricultural and fishery produce);

- the customs union;

- the common trade policy;

- the common foreign and security policy;

- the field of justice and home affairs (although each EFTA country is part of the Schengen area); and

- the economic and monetary union (EMU).

Switzerland

[edit]Switzerland, a member of EFTA but not of the EEA, participates in the single market with a number of exceptions, as defined by the Switzerland–European Union relations.[citation needed]

Western Balkans

[edit]Stabilisation and Association Agreement states have a "comprehensive framework in place to move closer to the EU and to prepare for [their] future participation in the Single Market".[161]

Turkey

[edit]Turkey has participated in the European Union–Turkey Customs Union since 1995, which enables it to participate in the free movement of goods (but not of agriculture or services, nor people) with the EU.[8]

Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine

[edit]Through the agreement of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), the three post-Soviet countries of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine were given access to the "four freedoms" of the EU single market: free movement of goods, services, capital, and people. Movement of people however, is in form of visa free regime for short stay travel, while movement of workers remains within the remit of the EU Member States.[7] The DCFTA is an "example of the integration of a Non-EEA-Member into the EU Single Market".[162]

Northern Ireland

[edit]The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland left the European Union at the end of January 2020 and left the single market in December 2020.[163] Under the terms of the Northern Ireland Protocol of the Brexit withdrawal agreement, Northern Ireland remains aligned to the European single market in a limited way to maintain an open border on the island of Ireland. This includes legislation on sanitary and phytosanitary standards for veterinary controls, rules on agricultural production/marketing, VAT and excise in respect of goods, and state aid rules.[164][165] It also introduces some controls on the flow of goods to Northern Ireland from Great Britain.

Under the terms of the Protocol, the Northern Ireland Assembly has the power by a simple majority to continue or terminate the protocol arrangements. In the event that consent to continue is not given, the arrangements would cease to apply after two years. The Joint Committee would make alternative proposals to the UK and EU to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland.[166]

Akrotiri and Dhekelia

[edit]Akrotiri and Dhekelia, the British Sovereign Base Areas, located on the island of Cyprus, are integral parts of the EU Customs Union, allowing goods to move freely.[167]

Further developments

[edit]Since 2015, the European Commission has been aiming to build a single market for energy.[168] and for the defence industry.[169]

On 2 May 2017, the European Commission announced a package of measures intended to enhance the functioning of the single market within the EU:[170]

- a single digital gateway based on an upgraded Your Europe portal, offering enhanced access to information, assistance services and online procedures throughout the EU[171]

- Single Market Information Tool (a proposed regulation under which the commission could require EU businesses to provide information in relation to the internal market and related areas where there is a suspicion that businesses are blocking the operation of the single market rules)[172]

- SOLVIT Action Plan (aiming to reinforce and improve the functioning of the existing SOLVIT network).

New Hanseatic League

[edit]The New Hanseatic League is a political grouping of economically like-minded northern European states, established in February 2018, that is pushing for a more developed European single market, particularly in the services sector.[173]

See also

[edit]- Law of the European Union

- Community preference

- Union State, a similar free movement zone for Russian and Belarusian citizens

Notes

[edit]- ^ The provision reads

3. The Union shall establish an internal market. It shall work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy, aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment. It shall promote scientific and technological advance.

— Treaty of Lisbon Article 3, point 3

- ^ Known also as "Single Market Act I", as a further set of priority actions, "Single Market Act II", were identified and adopted in 2012.[23]

- ^ At the time, TEEC article 30

References

[edit]- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org.

- ^ "General policy framework". ec.europa.eu. 30 October 2014. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "The European Single Market". Europa web portal. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Internal Market". European Commission. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Barnard, Catherine (2013). "Competence Review: The Internal Market" (PDF). Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Association agreement – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 11 June 2024. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ a b The EU-Ukraine Association Agreement and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area What's it all about?. European External Action Service. Archived 13 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b "Decision No 1/95 of the EC-Turkey Association Council of 22 December 1995 on implementing the final phase of the Customs Union" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2013.

- ^ "Brexit Agreement". EU Commission.

- ^ European Commission. "A Single Market for goods". Europa web portal. Archived from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- ^ Eur-Lex, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economc and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Common European Sales Law to facilitate Cross-Border Transactions in the Single Market, COM/2011/0636 final, "Context" section, published on 11 October 2011, accessed on 25 October 2025

- ^ European Commission, Completing the Single Market, archived on 17 February 2012

- ^ in ’t Veld, Jan (2019). "The economic benefits of the EU Single Market in goods and services". Journal of Policy Modeling. 41 (5): 803–818. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.06.004.

- ^ Cockfield, Arthur (1994). European Union: Creating The European Single Market. Wiley Chancery Law. ISBN 9780471952077. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Barnes, John (20 January 2007). "Lord Cockfield". The Independent. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ "Completing The Internal Market". European Union. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "EU glossary: Jargon S–Z". BBC News. 16 November 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "? – EUR-Lex". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Introduction – EU fact sheets – European Parliament". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Directive 96/71/EC

- ^ Directive 2006/123/EC

- ^ "Justice policies at a glance – European Commission". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ LexisNexis, Single Market Act I / II definition, accessed on 27 October 2025

- ^ Ceplis (21 June 2010). "Analysis of Professor Mario Monti's report: "A new strategy for the Single Market: At the service of Europe's Economy Strategy" – Some Suggestions on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications". CEPLIS. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ EUR-Lex, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Single Market Act II - Together for new growth, COM(2012) 573 final, page 5, published on 3 October 2012, accessed on 27 October 2025

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (5 June 2024). "Europe Has Fallen Behind the U.S. and China. Can It Catch Up?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ "High-profile report urges EU to create a 'fifth freedom' of research and innovation | Science|Business". sciencebusiness.net. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ Inman, Phillip (9 September 2024). "EU 'needs €800bn-a-year spending boost to avert agonising decline'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ a b Publications Office of the EU, Free movement of goods: Guide to the application of Treaty provisions governing the free movement of goods, page 9, © European Union, 2010. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Published 7 July 2010, accessed 3 January 2021

- ^ European Court of Justice, Sixth Chamber, Case C-97/98 Peter Jägerskiöld and Torolf Gustafsson on the interpretation of the rules of the EC Treaty on the free movement of goods and the freedom to provide services, 21 October 1999, accessed 3 January 2021

- ^ Official Journal of the European Communities, "Resolution of the Council and of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, Meeting Within the Council of 7 December 1998 on the free movement of goods", L337/10, accessed 1 January 2024.

- ^ Case 27/67 Fink-Frucht

- ^ "Brexit: Boris Johnson signs Brexit trade deal after MPs give overwhelming backing for EU agreement". Sky News. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ Case 7/68 Commission v Italy

- ^ Neither the purpose of the charge, nor its name in domestic law, is relevant.[34]

- ^ "? – EUR-Lex". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "? – EUR-Lex". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "? – EUR-Lex". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "? – EUR-Lex". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "? – EUR-Lex". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Case 323/87 Commission v Italy (Taxation of rum), 1989 ECR 2275.

- ^ P Craig and G de Búrca, EU Law: Text, Cases, and Materials (6th edn 2015) chs 18–19. C Barnard, The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms (4th edn 2013) chs 2–6

- ^ TFEU arts 28–30

- ^ (1974) Case 8/74, [1974] ECR 837

- ^ Previously TEEC article 30.

- ^ See D Chalmers et al, European Union Law (1st edn 2006) 662, "This is a ridiculously wide test."

- ^ Commission v Ireland (1982) Case 249/81

- ^ Commission v France (1997) C-265/95. See further K Muylle, 'Angry farmers and passive policemen' (1998) 23 European Law Review 467

- ^ Rasmussen, Scott (2011). "English Legal Terminology: Legal Concepts in Language, 3rd ed. By Helen Gubby. The Hague:Eleven International Publishing, 2011. Pp. 272. ISBN 978-90-8974-547-7. €35.00; US$52.50". International Journal of Legal Information. 39 (3): 394–395. doi:10.1017/s0731126500006314. ISSN 0731-1265. S2CID 159432182.

- ^ PreussenElektra AG v Schleswag AG (2001) C-379/98, [2001] ECR I-2099, [75]-[76]

- ^ "EUR-Lex – 61980CJ0053 – EN – EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ (2003) C-112/00, [2003] ECR I-5659

- ^ (2003) C-112/00, [79]-[81]

- ^ cf. Leppik (2006) C-434/04, [2006] ECR I‑9171, Opinion of AG Maduro, [23]-[25]

- ^ (2003) C-112/00, [2003] ECR I-5659, [77]. See ECHR articles 10 and 11.

- ^ Oebel (1981) Case 155/80

- ^ Mickelsson and Roos (2009) C-142/05

- ^ Vereinigte Familiapresse v Heinrich Bauer (1997) C-368/95

- ^ Dansk Supermarked A/S (1981) Case 58/80

- ^ See C Barnard, The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms (4th edn 2013) 172–173, listing the present state.

- ^ (1979) Case 170/78

- ^ (1979) Case 170/78, [13]-[14]

- ^ (1983) Case 261/81

- ^ (1983) Case 261/81, [17]

- ^ (2003) C-14/00, [88]-[89]

- ^ (2009) C-110/05, [2009] ECR I-519

- ^ (2009) C-110/05, [2009] ECR I-519, [56]. See also Mickelsson and Roos (2009) C-142/05, on prohibiting jet skis, but justified if proportionate towards the aim of safeguarding health and the environment.

- ^ (1993) C-267/91

- ^ See also Torfaen BC v B&Q plc (1989) C-145/88, holding the UK Sunday trading laws in the former Shops Act 1950 were probably outside the scope of article 34 (but not clearly reasoned). The "rules reflect certain political and economic choices" that "accord with national or regional socio-cultural characteristics."

- ^ cf Vereinigte Familiapresse v Heinrich Bauer (1997) C-368/95

- ^ (1997) C-34/95, [1997] ECR I-3843

- ^ (2001) C-405/98, [2001] ECR I-1795

- ^ Unfair Commercial Practices Directive 2005/29/EC

- ^ Capital Movement Directive 1988 (88/361/EEC) Annex I, including (i) investment in companies, (ii) real estate, (iii) securities, (iv) collective investment funds, (v) money market securities, (vi) bonds, (vii) service credit, (viii) loans, (ix) sureties and guarantees (x) insurance rights, (xi) inheritance and personal loans, (xii) physical financial assets (xiii) other capital movements.

- ^ (2000) C-251/98, [22]

- ^ e.g. Commission v Belgium (2000) C-478/98, holding that a law forbidding Belgian residents getting securities of loans on the Eurobond was unjustified discrimination. It was disproportionate in preserving, as Belgium argued, fiscal coherence or supervision.

- ^ See Commission v Netherlands (2006) C‑282/04, AG Maduro's Opinion on golden shares in KPN NV and TPG NV.

- ^ (2007) C-112/05

- ^ (2010) C-171/08

- ^ TFEU art 345

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 2560/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 2001 on cross-border payments in euro". EUR-lex – European Communities, Publications office, Official Journal L 344, 28 December 2001 P. 0013 – 0016. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ "Cross border payments in the EU, Euro Information, The Official Treasury Euro Resource". United Kingdom Treasury. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ European Central Bank. "TARGET". Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ See Delors Report, Report on Economic and Monetary Union in the EC (1988)

- ^ e.g. J Stiglitz, 'Too important for bankers' (11 June 2003) The Guardian and J Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality (2011) ch 9 and 349

- ^ Vértesy, László (2019). "The legal and regulatory aspects of the free movement of capital – towards the Capital Markets Union". Journal of Legal Theory HU (4): 110–128.

- ^ "Mid-term review of the capital markets union action plan". European Commission – European Commission. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Busch, Danny (1 September 2017). "A Capital Markets Union for a Divided Europe". Journal of Financial Regulation. 3 (2): 262–279. doi:10.1093/jfr/fjx002. hdl:2066/178372. ISSN 2053-4833.

- ^ Ringe, Wolf-Georg (9 March 2015). "Capital Markets Union for Europe – A Political Message to the UK". Rochester, NY. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2575654. S2CID 154764220. SSRN 2575654.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ See Asscher v Staatssecretaris van Financiën (1996) C-107/94, [1996] ECR I-3089, holding a director and sole shareholder of a company was not regarded as a "worker" with "a relationship of subordination".

- ^ See P Craig and G de Búrca, EU Law: Text, Cases, and Materials (6th edn 2015) ch 22. C Barnard, The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms (4th edn 2013) chs 10–11 and 13

- ^ (1995) C-55/94, [1995] ECR I-4165

- ^ Gebhard (1995) C-55/94, [37]

- ^ TFEU art 54 treats natural and legal persons in the same way under this chapter.

- ^ ITWF and Finnish Seamen's Union v Viking Line ABP and OÜ Viking Line Eesti (2007) C-438/05, [2007] I-10779, [34]

- ^ (1974) Case 2/74, [1974] ECR 631

- ^ See also Klopp (1984) Case 107/83, holding a Paris avocat requirement to have one office in Paris, though "indistinctly" applicable to everyone, was an unjustified restriction because the aim of keeping advisers in touch with clients and courts could be achieved by 'modern methods of transport and telecommunications' and without living in the locality.

- ^ (2011) C-565/08

- ^ (2011) C-565/08, [52]

- ^ Kamer van Koophandel en Fabrieken voor Amsterdam v Inspire Art Ltd (2003) C-167/01

- ^ cf Employee Involvement Directive 2001/86/EC

- ^ (1988) Case 81/87, [1988] ECR 5483

- ^ (1999) C-212/97, [1999] ECR I-1459. See also Überseering BV v Nordic Construction GmbH (2002) C-208/00, on Dutch minimum capital laws.

- ^ The classic arguments are found in WZ Ripley, Main Street and Wall Street (Little, Brown & Co 1927), Louis K. Liggett Co. v. Lee, 288 U.S. 517 (1933) per Brandeis J and W Cary, 'Federalism and Corporate Law: Reflections on Delaware' (1974) 83(4) Yale Law Journal 663. See further S Deakin, 'Two Types of Regulatory Competition: Competitive Federalism versus Reflexive Harmonisation. A Law and Economics Perspective on Centros' (1999) 2 CYELS 231.

- ^ (2002) C-208/00, [92]-[93]

- ^ (2008) C-210/06

- ^ See further National Grid Indus (2011) C-371/10 (an exit tax for a Dutch company required justification, not justified here because it could be collected at the time of transfer) and VALE Epitesi (2012) C-378/10 (Hungary did not need to allow an Italian company to register)

- ^ cf P Craig and G de Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials (2015) 815, "it seems that the CJEU's rulings, lacking any deep understanding of business law policies, have brought about other corporate law changes in Europe that were neither intended by the Court nor by policy-makers".

- ^ TFEU arts 56 and 57

- ^ (1974) Case 33/74

- ^ cf Debauve (1980) Case 52/79, art 56 does not apply to 'wholly internal situations' where an activity are all in one member state.

- ^ ECJ First Chamber, Omalet NV v. Rijksdienst voor Sociale Zekerheid, Case C-245/09, 22 December 2010, see also case C-108/98 RI.SAN (1999) ECR I-5219 and Case C-97/98 Jagerskiold (1999) ECR I-7319

- ^ Council Directive 71/304/EEC of 26 July 1971 concerning the abolition of restrictions on the freedom to provide services in respect of public works contracts and on the award of public works contracts to contractors acting through agencies or branches.

- ^ Belgium v Humbel (1988) Case 263/86, but contrast Schwarz and Gootjes-Schwarz v Finanzamt Bergisch Gladbach (2007) C-76/05

- ^ Wirth v Landeshauptstadt Hannover (1993) C-109/92

- ^ (2001) C-157/99, [2001] ECR I-5473

- ^ (2001) C-157/99, [48]-[55]

- ^ (2001) C-157/99, [94] and [104]-[106]

- ^ See Watts v Bedford Primary Care Trust (2006) C-372/04 and Commission v Spain (2010) C-211/08

- ^ (2010) C‑137/09, [2010] I-13019

- ^ (1995) C-384/93, [1995] ECR I-1141

- ^ (2004) C-36/02, [2004] ECR I-9609

- ^ (2009) C‑42/07, [2007] ECR I-7633

- ^ 2006/123/EC

- ^ "Digital Single Market". Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (6 May 2015). "EU unveils plans to set up digital single market for online firms". The Guardian.

- ^ "Free movement of persons | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament". Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ European Commission. "Living and working in the Single Market". Europa web portal. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- ^ Maas, Willem (2007). Creating European Citizens. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5485-6.

- ^ P Craig and G de Búrca, EU Law: Text, Cases, and Materials (6th edn 2015) ch 21. C Barnard, The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms (4th edn 2013) chs 8–9 and 12–13

- ^ See P Craig and G de Burca, European Union Law (2003) 701, there is a tension 'between the image of the Community worker as a mobile unit of production, contributing to the creation of a single market and to the economic prosperity of Europe' and the 'image of the worker as a human being, exercising a personal right to live in another state and to take up employment there without discrimination, to improve the standard of living of his or her family'.

- ^ Defrenne v Sabena (No 2) (1976) Case 43/75, [10]

- ^ Lawrie-Blum v Land Baden-Württemberg (1986) Case 66/85, [1986] ECR 2121

- ^ (1988) Case 196/87, [1988] ECR 6159

- ^ Dano v Jobcenter Leipzig (2014) C‑333/13

- ^ Angonese v Cassa di Risparmio di Bolzano SpA (2000) C-281/98, [2000] ECR I-4139

- ^ Free Movement of Workers Regulation 492/2011 arts 1–4

- ^ (1995) C-415/93

- ^ (1989) Case 379/87, [1989] ECR 3967

- ^ (2000) C-281/98, [2000] ECR I-4139, [36]-[44]

- ^ (1995) C-279/93

- ^ (2004) C-387/01, [54]-[55]

- ^ (2007) C-287/05, [55]

- ^ (2007) C-213/05

- ^ Hartmann v Freistaat Bayern (2007) C-212/05. Discussed in C Barnard, The Substantive Law of the European Union (2013) ch 9, 293–294

- ^ See Van Duyn v Home Office Case 41/74, [1974] ECR 1337

- ^ See NN Shuibhne, 'The Resilience of EU Market Citizenship' (2010) 47 CMLR 1597 and HP Ipsen, Europäisches Gemeinschaftsrecht (1972) on the concept of a 'market citizen' (Marktbürger).

- ^ Grzelczyk v Centre Public d’Aide Sociale d’Ottignes-Louvain-la-Neuve (2001) C-184/99, [2001] ECR I-6193

- ^ See T Marshall, Citizenship and Social Class (1950) 28-9, positing that 'citizenship' passed from civil rights, political rights, to social rights, and JHH Weiler, 'The European Union belongs to its citizens: Three immodest proposals' (1997) 22 European Law Review 150

- ^ 5th Report on Citizenship of the Union COM(2008) 85. The "First Annual Report on Migration and Integration" COM(2004) 508, found by 2004, 18.5m third country nationals were resident in the EU.

- ^ CRD 2004 art 2(2) defines 'family member' as a spouse, long term partner, descendant under 21 or depednant elderly relative that is accompanying the citizen. See also Metock v Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform (2008) C-127/08, holding that four asylum seekers from outside the EU, although they did not lawfully enter Ireland (because their asylum claims were ultimately rejected) were entitled to remain because they had lawfully married EU citizens. See also, R (Secretary of State for the Home Department) v Immigration Appeal Tribunal and Surinder Singh [1992] 3 CMLR 358

- ^ (1998) C-85/96, [1998] ECR I-2691

- ^ (2004) C-456/02, [2004] ECR I-07573

- ^ (2001) C-184/99, [2001] ECR I-6193

- ^ (2005) C-209/03, [2005] ECR I-2119

- ^ (2005) C-147/03

- ^ (2014) C‑333/13

- ^ European Commission, Legal rules and implementation. Retrieved 16 May 2017

- ^ European Commission, Commission Interpretative Communication on the Community law applicable to contract awards not or not fully subject to the provisions of the Public Procurement Directives, published 1 August 2006, accessed 1 June 2021

- ^ "Introduction – Fact sheets on the European Union – At your service". European Parliament. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ EU and Serbia: enhanced cooperation rules enter into force. European Commission Press Release Databease. Published on 31 August 2013.

- ^ EU-Ukraine Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. European External Action Service. Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Edgington, Tom (2 March 2020). "Which countries does the UK do the most trade with?". BBC News.

- ^ "Questions & Answers: EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement". European Commission. 24 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "Brexit Agreement". EU Commission.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Protocol". Institute For Government. 19 December 2019.

- ^ Protocol relating to the Sovereign Base Areas of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in Cyprus Archived 11 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, EUR-Lex, 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Priority Policy Area: A fully-integrated internal energy market". Europa. European Commission. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "EU to support common defense market, boost joint spending". Deutsche Welle. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Commission takes new steps to enhance compliance and practical functioning of the EU Single Market". Europa (Press release). Brussels: European Commission. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 October 2018 establishing a single digital gateway to provide access to information, to procedures and to assistance and problem-solving services and amending Regulation (EU) No 1024/2012". EUR-Lex. EU Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. 2 October 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council setting out the conditions and procedure by which the Commission may request undertakings and associations of undertakings to provide information in relation to the internal market and related areas". EUR-Lex. EU Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ "The EU's new Hanseatic League picks its next Brussels battle". Financial Times. October 2018. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

Bibliography and further reading

[edit]- Books

- Barnard, Catherine (2010). The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms (3rd ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929839-6.

- Chalmers, D.; et al. (2010). European Union Law: Text and Materials (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12151-4.

- Vaughan, David; Robertson, Aidan, eds. (2003). Law of the European Union. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-904501-11-4.

(looseleaf since)

- Butler, Graham, ed. (2025). Research Handbook on EEA Internal Market Law. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-80392-245-4.

- Groussot, Xavier; Öberg, Marja-Liisa; Butler, Graham, eds. (2025). The EU Law of Investment: Past, Present, and Future. Swedish Studies in European Law. Oxford: Hart Publishing/Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-50996-585-4.

- Articles

- Easson (1980). "The Spirits, Wine and Beer Judgments: A Legal Mickey Finn?". European Law Review. 5: 318.

- Easson (1984). "Cheaper wine or Dearer Beer?". European Law Review. 9: 57.

- Hedemann-Robinson (1995). "Indirect Discrimination: Article 95(1) EC Back to Front and Inside Out". European Public Law. 1: 439–468. doi:10.54648/EURO1995048. S2CID 143943870.

- Danusso; Denton (1990). "Does the European Court of Justice Look for a Protectionist Motive under Article 95?". Legal Issues of Economic Integration. 1: 67–120. doi:10.54648/LEIE1990002. S2CID 156285940.

- Gormley, Laurence W (2008). "Silver Threads among the Gold: 50 years of the free movement of goods". Fordham International Law Journal. 31: 601.

- Szczepanski, Marcin (2013). Further steps to complete the Single Market (PDF). Library of the European Parliament. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2017.

External links

[edit]European single market

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins in Post-War Integration