Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

The signing ceremony of the Treaty of Lisbon on 13 December 2007 which gave the TFEU its current name | |

| Type | Founding treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | 25 March 1957 |

| Location | Capitoline Hill in Rome, Italy |

| Effective | 1 January 1958 (1 December 2009 under its current name) |

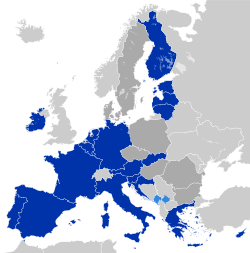

| Parties | EU member states |

| Depositary | Government of Italy |

| Full text | |

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is one of two treaties forming the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU), the other being the Treaty on European Union (TEU). It was previously known as the Treaty Establishing the European Community (TEC).[1]

The Treaty originated as the Treaty of Rome (fully the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), which brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best-known of the European Communities (EC). It was signed on 25 March 1957 by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany and came into force on 1 January 1958. It remains one of the two most important treaties in the modern-day European Union (EU).

Its name has been amended twice since 1957. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 removed the word "economic" from the Treaty of Rome's official title and, in 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon renamed it the "Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union".

Following the 2005 referendums, which saw the failed attempt at launching a European Constitution, on 13 December 2007 the Lisbon Treaty was signed. This saw the 'TEC' renamed as the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and, once again, renumbered. The Lisbon reforms resulted in the merging of the three pillars into the reformed European Union.[2]

In March 2011, the European Council adopted a decision to amend the Treaty by adding a new paragraph to Article 136. The additional paragraph, which enables the establishment of a financial stability mechanism for the Eurozone, runs as follows:

The Member States whose currency is the euro may establish a stability mechanism to be activated if indispensable to safeguard the stability of the euro area as a whole. The granting of any required financial assistance under the mechanism will be made subject to strict conditionality. [3]

Present contents

[edit]The consolidated TFEU consists of seven parts:

Part 1, Principles

[edit]In principles, article 1 establishes the basis of the treaty and its legal value. Articles 2 to 6 outline the competencies of the EU according to the level of powers accorded in each area. Articles 7 to 14 set out social principles, articles 15 and 16 set out public access to documents and meetings and article 17 states that the EU shall respect the status of religious, philosophical and non-confessional organisations under national law.[4]

Part 2, Non-discrimination and citizenship of the Union

[edit]The second part begins with article 18 which outlaws, within the limitations of the treaties, discrimination on the basis of nationality. Article 19 states the council with the consent of the European Parliament "may take appropriate action to combat discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation". Articles 20 to 24 establishes EU citizenship and accords rights to it; to free movement, consular protection from other states, vote and stand in local and European elections, right to petition Parliament and the European Ombudsman and to contact and receive a reply from EU institutions in their own language. Article 25 requires the commission to report on the implementation of these rights every three years.[4]

Part 3, Union policies and internal actions

[edit]Part 3 is the largest in the TFEU. Articles 26 to 197 concern the substantive policies and actions of the EU.

Title I: Internal market

[edit]Title II: Free movement of goods

[edit]Including the customs union

Title III: Agriculture and Fisheries

[edit]Common Agricultural Policy and Common Fisheries Policy

Title IV: Free movement of workers, services and capital

[edit]Title IV concerns free movement of people, services and capital:

- Chapter 1: Workers (articles 45–48, ex articles 39–42 TEC), including the right to move freely in order to "accept [an] offer of employment actually made[5]

- Chapter 2: Right of Establishment (articles 49–55), including the right to take up and pursue activities as [a] self-employed person[6]

- Chapter 3: Services (articles 56–62)[7]

- Chapter 4: Capital and Payments (articles 63–66), including free movement of "capital between member states and between member states and third countries".[8]

Title V: Area of freedom, justice and security

[edit]Including police and justice co-operation

Title VI: Transport

[edit]Title VII: Common Rules on Competition, Taxation and Approximation of Laws

[edit]European Union competition law, taxation and harmonisation of regulations (note Article 101 and Article 102)

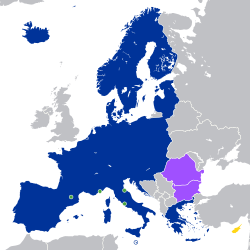

Title VIII: Economic and monetary policy

[edit]Articles 119 to 144 concern economic and monetary policy, including articles on the euro. Chapter 1: Economic policy - Article 122 deals with unforeseen problems in the supply chain and "severe difficulties caused by natural disasters or exceptional occurrences beyond its control"[9][10] Chapter 1: Economic policy – Article 126 deals with how excessive member state debt is handled.[11] Chapter 2: Monetary policy – Article 127 outlines that the European System of Central Banks should maintain price stability and work with the principles of an open markets and free competition.[12] The Article 140 describes the criteria for inclusion in monetary union (the euro) or having exception from it, and also says that it is a majority of the council, not the state alone, which decides upon usage of euro or national currency. Thereby are states obliged (except UK and Denmark) to introduce the euro if the council finds they fulfil the criteria.

Titles IX to XV: Employment, social and consumer policy

[edit]Title IX concerns employment policy, under articles 145–150. Title X concerns social policy, and with reference to the European Social Charter 1961 and the Community Charter of the Fundamental Social Rights of Workers 1989. This gives rise to the weight of European labour law.

Title XI establishes the European Social Fund under articles 162–164. Title XII, articles 165 and 166 concern education, vocational training, youth and sport policies. Title XIII concerns culture, in article 167. Title XIV allows measures for public health, under article 168. Title XV empowers the EU to act for consumer protection, in article 169.

Titles XVI to XXIV: Networks, industry, environment, energy, other

[edit]Title XVI, articles 170–172 empower action to develop and integrate Trans-European Networks. Title XVII, article 173, regards the EU's industrial policy, to promote industry. Title XVIII, articles 174 to 178 concern economic, social and territorial cohesion (reducing disparities in development). Title XIX concerns research and development and space policy, under which the European Research Area and European Space Policy are developed.

Title XX concerns the increasingly important environmental policy, allowing action under articles 191 to 193. Title XXI, article 194, establishes the Energy policy of the European Union.

Title XXII, article 195 is tourism. Title XXIII, article 196 is civil protection. Title XXIV, article 197 is administrative co-operation.

Part 4, Association of the overseas countries and territories

[edit]Part 4, in articles 198 to 204, deals with association of overseas territories. Article 198 sets the objective of association as promoting the economic and social development of those associated territories as listed in annexe 2. The following articles elaborate on the form of association such as customs duties.[4]

Part 5, External action by the Union

[edit]Part 5, in articles 205 to 222, deals with EU foreign policy. Article 205 states that external actions must be in accordance with the principles laid out in Chapter 1 Title 5 of the Treaty on European Union. Article 206 and 207 establish the common commercial (external trade) policy of the EU. Articles 208 to 214 deal with co-operation on development and humanitarian aid for third countries. Article 215 deals with sanctions while articles 216 to 219 deal with procedures for establishing international treaties with third countries. Article 220 instructs the High Representative and Commission to engage in appropriate co-operation with other international organisations and article 221 establishes the EU delegations. Article 222, the Solidarity clause states that members shall come to the aid of a fellow member who is subject to a terrorist attack, natural disaster or man-made disaster. This includes the use of military force.[4]

Part 6, Institutional and financial provisions

[edit]Part 6, in articles 223 to 334, elaborates on the institutional provisions in the Treaty on European Union. As well as elaborating on the structures, articles 288 to 299 outline the forms of legislative acts and procedures of the EU. Articles 300 to 309 establish the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank. Articles 310 to 325 outline the EU budget. Finally, articles 326 to 334 establishes provision for enhanced co-operation.[4]

Part 7, General and final provisions

[edit]Part 7, in articles 335 to 358, deals with final legal points, such as territorial and temporal application, the seat of institutions (to be decided by member states, but this is enacted by a protocol attached to the treaties), immunities and the effect on treaties signed before 1958 or the date of accession.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nugent, Nigel (2017). The Government and Politics of the European Union. Red Globe Press.

- ^ "Presidency Conclusions Brussels European Council 21/22 June 2007" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 23 June 2007.

- ^ De Witte, Bruno (2011). "The European Treaty Amendment for the Creation of a Financial Stability Mechanism" (PDF). European Policy Analysis. 2011 (6). Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies (SIEPS). Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ^ Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union - PART THREE: UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS - TITLE IV: FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS, SERVICES AND CAPITAL - Chapter 1: Workers - Article 45 (ex Article 39 TEC)

- ^ Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union - PART THREE: UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS - TITLE IV: FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS, SERVICES AND CAPITAL - Chapter 2: Right of establishment - Article 49 (ex Article 43 TEC)

- ^ Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union - PART THREE: UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS - TITLE IV: FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS, SERVICES AND CAPITAL - Chapter 3: Services - Article 56 (ex Article 49 TEC)

- ^ Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union - PART THREE: UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS - TITLE IV: FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS, SERVICES AND CAPITAL - Chapter 4: Capital and payments - Article 63 (ex Article 56 TEC)

- ^ Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union PART THREE - UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS TITLE VIII - ECONOMIC AND MONETARY POLICY Chapter 1 - Economic policy Article 122 (ex Article 100 TEC)

- ^ Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (29 January 2021). "EU threatens war-time occupation of vaccine makers as AstraZeneca crisis spirals". Telegraph Media Group Limited.

- ^ Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union - PART THREE: UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS - TITLE VIII: ECONOMIC AND MONETARY POLICY - Chapter 1: Economic policy - Article 126 (ex Article 104 TEC)

- ^ Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union - PART THREE: UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS - TITLE VIII: ECONOMIC AND MONETARY POLICY - Chapter 2: Monetary policy - Article 127 (ex Article 105 TEC)

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins in the Treaty of Rome and subsequent amendments

The Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC Treaty), signed on 25 March 1957 by the governments of Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the Federal Republic of Germany, entered into force on 1 January 1958.[5][2] Its core provisions established a customs union, harmonized economic policies in agriculture, transport, and competition, and set the framework for an internal market based on the free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital, which directly underpin the operational and policy-making structures of the modern Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).[2] The EEC Treaty underwent multiple amendments to expand competences, streamline decision-making, and accommodate institutional growth. The Merger Treaty, signed on 8 April 1965 and effective from 1 July 1967, integrated the executives of the EEC, European Coal and Steel Community, and Euratom into a single Commission and Council, rationalizing administrative functions without altering substantive policies.[5] The Single European Act, signed on 17 February 1986 and entering into force on 1 July 1987, introduced qualified majority voting in the Council for internal market measures, set a deadline of 31 December 1992 for completing the single market, and added environmental and regional development policies to the EEC's scope.[5] The Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty), signed on 7 February 1992 and effective from 1 November 1993, renamed the EEC Treaty as the Treaty establishing the European Community (EC Treaty), established European Union citizenship, laid foundations for economic and monetary union leading to the euro, and introduced a three-pillar structure separating Community matters from intergovernmental cooperation in foreign, security, and justice affairs, while broadening EC competences in areas like consumer protection and trans-European networks.[5][1] Subsequent revisions included the Treaty of Amsterdam, signed on 2 October 1997 and entering into force on 1 May 1999, which integrated Schengen rules on border-free travel into the EC pillar, enhanced employment policy coordination, and reassigned certain justice and home affairs competences to Community level;[5] and the Treaty of Nice, signed on 26 February 2001 and effective from 1 February 2003, which adjusted voting weights in the Council and extended qualified majority voting to facilitate enlargement to 25 members by reweighting institutional balances.[5] The Treaty of Lisbon, signed on 13 December 2007 and entering into force on 1 December 2009, fundamentally restructured the framework by renaming the EC Treaty as the TFEU, consolidating its provisions with the Treaty on European Union into a two-treaty system, eliminating the three-pillar structure to unify external representation and legal personality, introducing the ordinary legislative procedure (co-decision) as the norm, and renumbering articles for systematic clarity while preserving the substantive content derived from the original EEC Treaty.[5][1] These amendments cumulatively transformed the Treaty of Rome's economic focus into a comprehensive legal basis for EU governance, emphasizing shared competences in internal policies without supplanting national sovereignty in unallocated areas.[1]Negotiation and adoption via the Lisbon Treaty

The negotiation of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) formed part of the intergovernmental efforts to reform the European Union's institutional framework after the failure of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe, rejected in referendums in France on 29 May 2005 and the Netherlands on 1 June 2005.[6] The European Council, in its meeting of 21-22 June 2007, agreed to convene an Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) to draft a Reform Treaty amending the existing Treaty on European Union (TEU) and Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC), while preserving key substantive changes from the defunct constitutional treaty but without its symbolic elements like flags or anthems.[7] This approach aimed to enhance decision-making efficiency post-2004 and 2007 enlargements, including by consolidating the three-pillar structure into a unified legal framework.[8] The IGC mandate, adopted by the European Council on 23 June 2007, outlined specific reforms, such as renaming the TEC as the TFEU to reflect its focus on operational provisions, reorganizing competences, and integrating former Community pillars into the TFEU's structure for policies like the internal market and economic integration.[1] Negotiations commenced on 23 July 2007 under the Portuguese Presidency of the Council of the EU, involving detailed discussions among the 27 member states on institutional balances, including qualified majority voting extensions and the role of the European Parliament.[9] The conference concluded its work in October 2007, producing a draft treaty text that replaced the TEC with the TFEU, which organizes the Union's functioning, delineates competences (exclusive, shared, and supporting), and details policy areas from free movement to external action.[4] Adoption occurred through the signing of the Treaty of Lisbon on 13 December 2007 by the heads of state or government of the 27 EU member states, in the presence of European Parliament President Hans-Gert Pöttering, at the Hieronymites Monastery in Lisbon, Portugal.[10] The Lisbon Treaty thereby incorporated the TFEU as one of its two core components alongside the amended TEU, with the TFEU comprising 358 articles structured into six titles covering principles, citizenship rights, policies, and institutions.[11] This signing marked the formal adoption, pending ratification by all member states, which ultimately enabled the TFEU's entry into force on 1 December 2009.[1]Ratification process and entry into force on 1 December 2009

The Treaty of Lisbon was signed on 13 December 2007 in Lisbon, Portugal, by the heads of state or government and foreign ministers of the 27 European Union member states, amending the Treaty establishing the European Community to form the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).[5] [10] Ratification required approval by each member state in accordance with its constitutional rules, typically through parliamentary vote, though Ireland mandated a referendum.[12] Ratification proceeded swiftly in many states, with Hungary approving it first on 17 December 2007 and Slovenia following on 29 January 2008.[9] Progress stalled after Ireland's referendum on 12 June 2008 rejected the treaty by 53.4% to 46.6%, prompting a crisis as unanimous ratification was required.[13] To address concerns, EU leaders offered Ireland legally binding guarantees on issues like neutrality, taxation, and social policies, leading to a second referendum on 2 October 2009, which passed with 67.1% approval.[14] Other challenges included Germany's Federal Constitutional Court review, which upheld the treaty on 30 June 2009 after legal challenges on sovereignty grounds, and the Czech Republic, where President Václav Klaus delayed signing until 3 November 2009 despite parliamentary approval in May 2009 and a Constitutional Court ruling in favor.[15] Klaus cited concerns over references to World War II history but proceeded after receiving an opt-out protocol on non-EU citizens.[16] With the Czech instrument of ratification deposited on 3 November 2009, all 27 member states had completed the process, enabling the treaty to enter into force on 1 December 2009 as stipulated.[15] [5] This activated the TFEU, renaming and restructuring the former EC Treaty while incorporating Lisbon's reforms on EU institutions, competences, and policies.[10]Legal Status and Framework

Distinction and interplay with the Treaty on European Union

The Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) constitute the core treaties underpinning the European Union, with both possessing identical legal value as affirmed in Article 1 of the TEU. The TEU establishes the Union's foundational elements, including its objectives (Article 3), values such as respect for human dignity, democracy, and the rule of law (Article 2), and principles governing competences like conferral, subsidiarity, and proportionality (Article 5). It also delineates the institutional framework (Title III, Articles 13–19), democratic mechanisms involving national parliaments and citizens (Title II, Articles 9–12), enhanced cooperation (Article 20), and general provisions for external action under the Common Foreign and Security Policy (Title V, Articles 21–46).[17] In distinction, the TFEU focuses on the operational and policy-specific dimensions, organizing Union competences into exclusive, shared, and supporting categories (Article 3–6) and detailing sectoral policies such as the internal market (Articles 26–27), free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital (Part Three, Title II), competition rules (Articles 101–109), economic and monetary policy (Articles 119–144), and external commercial relations (Articles 206–207).[18] The interplay between the TEU and TFEU is characterized by mutual reinforcement and cross-referencing, ensuring the Union's constitutional aspirations translate into enforceable mechanisms. The TEU provides overarching normative guidance, while the TFEU supplies the procedural and substantive tools for execution; for example, TEU Article 13 mandates that Union institutions act within the limits of the treaties, with operational specifics for bodies like the Council and Commission elaborated in TFEU Articles 230–243 and 289–297.[17] Conversely, TFEU provisions frequently defer to TEU principles, such as Article 205 requiring external action to comply with TEU Title V objectives, and Article 352's flexibility clause being constrained by TEU Article 5 on subsidiarity to prevent competence creep.[18] This symbiotic structure, consolidated under the 2007 Lisbon Treaty, integrates former European Community pillars into a unified framework, transferring detailed justice and home affairs rules to TFEU Title V (Articles 67–89) while reserving intergovernmental elements like CFSP primarily to the TEU.[19] Such delineation mitigates risks of institutional overreach by anchoring policy implementation in the TEU's subsidiarity safeguards, as evidenced in TEU Article 8's judicial review mechanism for competence violations, actionable via TFEU Article 263 proceedings before the Court of Justice. Protocols annexed to both treaties further harmonize application, such as those on the European Central Bank (Protocol No. 4) linking monetary policy execution in TFEU Article 127 to TEU economic objectives. This architecture promotes efficiency in decision-making—e.g., qualified majority voting in the Council under TEU Article 16, detailed in TFEU Article 238—while preserving member state sovereignty through explicit competence limits.[17][18]Principles of supremacy, direct effect, and primacy over national law

The principle of direct effect holds that certain provisions of EU law, including those in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), create enforceable rights for individuals that national courts must recognize and apply. This doctrine originated in the Court of Justice of the European Union's (CJEU) judgment in Case 26/62 Van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen on 5 February 1963, where the Court ruled that provisions of the then-EEC Treaty prohibiting member states from imposing new customs duties were sufficiently clear, precise, and unconditional to confer direct effect vertically against the state.[20][21] Direct effect applies to TFEU primary law provisions meeting these criteria, as well as to secondary legislation: Article 288 TFEU stipulates that regulations have general application, are binding in their entirety, and are directly applicable in all member states without need for national transposition.[22] Directives, while binding as to the result to be achieved per Article 288 TFEU, possess vertical direct effect if clear and unconditional once the transposition deadline passes, but lack horizontal direct effect between private parties, as affirmed in subsequent CJEU case law like Case 43/75 Defrenne v SABENA.[20][22] The principle of supremacy, also termed primacy, establishes that EU law, including TFEU provisions, prevails over conflicting national law, rendering the latter inapplicable by national authorities or courts. This was articulated by the CJEU in Case 6/64 Flaminio Costa v ENEL on 15 July 1964, where the Court held that the EEC Treaty created a new legal order integrated into national systems, such that subsequent or prior national measures incompatible with it must yield, regardless of their hierarchical status domestically.[23][24] Supremacy ensures uniform application of TFEU rules on competences, internal market freedoms (Articles 26–36, 45–66 TFEU), and other areas, overriding national laws even if adopted later, as the principle stems from the treaties' aim to create an autonomous legal system not subordinate to member states' constitutional provisions.[23] Although neither direct effect nor supremacy is explicitly codified in the TFEU text, their status was reaffirmed politically via Declaration No. 17 annexed to the Final Act of the 2007 Lisbon Treaty, which entered into force on 1 December 2009 and consolidated the TFEU. The Declaration states that the absence of primacy's explicit inclusion "shall not in any way change the existence of the principle and the existing case law of the Court of Justice," confirming these judge-made doctrines as foundational to the TFEU's effectiveness.[25] Together, direct effect and primacy enable TFEU provisions to bypass national implementation gaps, fostering a "complete system of legal norms" where individuals can enforce rights directly, and national judges disapply conflicting domestic rules, as reinforced in cases like Simmenthal (Case 106/77, 1978).[23] These principles, while rooted in CJEU jurisprudence rather than treaty text, underpin the TFEU's role in limiting member state sovereignty in shared competences (Article 2(2) TFEU) and ensuring causal efficacy of EU obligations over national divergences.[26]Categorization of EU competences: exclusive, shared, and supporting

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) delineates the European Union's competences in Title I, establishing a framework that limits Union action to areas explicitly conferred by the Member States, as per Article 5(2) TEU, to preserve national sovereignty where not delegated.[18] Article 2 TFEU categorizes these into exclusive competences, where only the Union may legislate and adopt legally binding acts; shared competences, where the Union and Member States may legislate, but Member States cease to authorize thereafter or retain complementary powers; and supporting competences, where the Union acts only to support, coordinate, or supplement Member State actions without harmonizing national laws or superseding state competences.[18] This structure, introduced by the Lisbon Treaty effective 1 December 2009, aims to clarify the vertical division of powers post the failed Constitutional Treaty, ensuring proportionality and subsidiarity in Union decision-making.[27] Exclusive competences, outlined in Article 3 TFEU, encompass five policy domains where Member States have irrevocably transferred authority, precluding national legislation unless delegated by the Union: the customs union; the rules on competition necessary for the functioning of the internal market; monetary policy for Member States whose currency is the euro; conservation of marine biological resources under the common fisheries policy; and the common commercial policy, including principles governing relations with third countries in trade matters.[18] In these areas, the Union's actions, such as tariff-setting under the customs union or exclusive external trade negotiations, directly bind Member States without scope for unilateral deviation, as affirmed by Court of Justice jurisprudence emphasizing the uniformity essential for single market integrity.[18] Shared competences, per Article 4 TFEU, apply to thirteen fields where the Union shares legislative authority with Member States, exercising it to the extent necessary for Treaty objectives, after which Member States may not enact conflicting measures but retain residual powers in undefined aspects: the internal market; social policy for aspects defined in the Treaty; economic, social, and territorial cohesion; agriculture and fisheries, excluding conservation of marine biological resources; environment; consumer protection; transport; trans-European networks; energy; the area of freedom, security, and justice; common safety concerns in public health; and, with qualifications, research, technological development, and space (where Union framework programs do not preclude Member State initiatives), as well as development cooperation and humanitarian aid (where a common Union policy coordinates but does not supplant national efforts).[18] This category enables harmonization directives, such as those approximating environmental standards, but requires exhaustion of Union action before Member State resumption, subject to subsidiarity review under Article 5(3) TEU.[18] Supporting competences, under Article 6 TFEU, permit Union involvement solely through incentives, coordination, or complementary measures in eight non-exhaustive areas, without entailing harmonization or infringement on Member State primacy: protection and improvement of human health; industry; culture; tourism; education, vocational training, youth, and sport; civil protection; and administrative cooperation between Member States and the Union.[18] Distinct from shared competences, these actions—such as funding programs for cultural heritage or health research coordination—rely on soft law like recommendations or open methods of coordination, preserving national implementation autonomy, as evidenced in Union initiatives like the European Health Union framework post-2020 which supplements rather than overrides state health systems.[18] Coordination of economic and employment policies under Article 5 TFEU, involving Council guidelines and monitoring, operates similarly within this supportive paradigm to foster convergence without binding legislation.[18]Foundational Principles

Common provisions on objectives, values, and categories of competences

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), read in conjunction with the Treaty on European Union (TEU), establishes the Union's foundational objectives primarily in Article 3 TEU, which delineate the internal and external aims guiding EU action. Internally, these include promoting peace, the Union's values, and the well-being of its peoples; establishing an internal market with economic, social, and territorial cohesion; achieving sustainable development based on balanced economic growth, price stability, full employment, and social progress; and fostering solidarity among Member States while combating social exclusion and discrimination. Externally, the objectives encompass upholding and promoting the Union's values and interests, contributing to peace, security, global sustainable development, solidarity, mutual respect, free and fair trade, poverty eradication, and protection of human rights, in particular through multilateral cooperation.[28] These objectives serve as a framework for interpreting and applying specific TFEU provisions, ensuring actions align with the Union's overarching goals without expanding competences beyond those delimited.[4] The Union's values, enshrined in Article 2 TEU, form the ethical and normative basis for all EU institutions, policies, and Member State compliance, stating that the Union is founded on respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, and respect for human rights, including rights of minorities, within a society characterized by pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity, and equality between women and men. These values are binding on Member States as preconditions for membership under Article 49 TEU and underpin enforcement mechanisms such as Article 7 TEU for systemic threats. While not directly operationalizing standalone competences in the TFEU, they inform the interpretation of TFEU provisions, such as non-discrimination rules in Articles 18-25 TFEU, and provide grounds for infringement actions where Member State actions undermine them, as affirmed in Court of Justice jurisprudence linking Article 2 TEU to broader treaty obligations.[28][3] Categories of competences, detailed in Articles 2 to 6 TFEU, delineate the scope of Union authority to act, categorizing them as exclusive, shared, coordinating, or complementary, thereby limiting EU intervention to enumerated areas and preserving subsidiarity and proportionality per Article 5 TEU. Exclusive competences (Article 2(1) and Article 3 TFEU) reserve sole authority to the Union in customs union; competition rules necessary for the internal market; monetary policy for Member States in the euro area; conservation of marine biological resources under common fisheries policy; and common commercial policy, with implied exclusivity extending to international agreements where Union legislation provides the legal basis (Article 3(2) TFEU). Shared competences (Article 2(2) and Article 4 TFEU) apply concurrently with Member States in internal market; social policy; economic, social, and territorial cohesion; agriculture and fisheries (except conservation); environment; consumer protection; transport; trans-European networks; energy; space; and common safety concerns in public health, with Member States regaining competence post-exhaustion of Union objectives in some areas like social policy.[4] Coordinating competences (Article 2(3)-(4) TFEU) require Member States to coordinate economic and employment policies within Union arrangements, without supplanting national prerogatives, as in Articles 119-120 TFEU for economic coordination and Article 148 TFEU for employment guidelines. Complementary or supporting competences (Article 2(5) and Article 6 TFEU) enable Union action to support, coordinate, or supplement Member State efforts without harmonizing laws, covering protection and improvement of human health; industry; culture; tourism; education, vocational training, youth, and sport; civil protection; and administrative cooperation, emphasizing non-preemption of national measures. Article 6 further specifies fields like environment and transport as shared and lists areas for supporting action, ensuring competences remain confined to treaty enumeration to prevent competence creep, as reinforced by the principle of conferral in Article 5(2) TEU.[4] These categorizations, introduced by the Lisbon Treaty effective 1 December 2009, aim to enhance transparency and democratic accountability by clarifying boundaries between Union and national powers.[28]Non-discrimination, equality, and Union citizenship rights

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) establishes a general prohibition on discrimination on grounds of nationality within the scope of application of the Treaties, as provided in Article 18.[29][30] This principle applies to Union citizens and ensures equal treatment among nationals of different Member States in areas governed by EU law, such as free movement and internal market rules, without prejudice to special provisions in the Treaties or secondary legislation.[31] Article 19 empowers the Council, acting unanimously after consulting the European Parliament, to take appropriate action to combat discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age, or sexual orientation, including legislative measures to address such discrimination in areas of Union competence.[32][31] Equality provisions in the TFEU focus primarily on economic and social dimensions, with Article 157 mandating the principle of equal pay for male and female workers for equal work or work of equal value.[33][34] This requires Member States to ensure the application of equal pay, including the same unit of measurement for work based on time or piece rates, and opposes any pay discrimination arising from sex-based occupational classifications.[33] The provision has direct effect, allowing individuals to invoke it before national courts, and extends to comparisons within the same establishment or service where pay structures originate from a single source.[35] Article 153 further supports equal treatment in employment and occupation, underpinning Union action on equal opportunities without harmonizing social security systems.[36] Union citizenship, codified in Part Two of the TFEU (Articles 20–25), confers additional rights on every person holding the nationality of a Member State, complementing national citizenship without replacing it.[37][31] Article 20(2) grants the right to move and reside freely within Member States' territories, subject to limitations and conditions in the Treaties and secondary measures adopted to facilitate this right.[38][39] Specific entitlements include the right to vote and stand as a candidate in municipal elections and elections to the European Parliament in the Member State of residence (Article 22), subject to procedural safeguards ensuring no abuse.[40] Union citizens also benefit from diplomatic and consular protection by any Member State in a third country where their home state is unrepresented (Article 23), and the right to petition the European Parliament or complain to the European Ombudsman (Article 24).[37] These rights reinforce non-discrimination by nationality and apply alongside free movement directives, though they do not extend automatically to economically inactive citizens without sufficient resources to avoid becoming a burden on the host state's social assistance system.[31]Internal Market and Economic Integration

Free movement provisions for goods, persons, services, and capital

The free movement provisions of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) constitute the foundational elements of the EU's internal market, as articulated in Article 26, which defines the internal market as "an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured".[31] These provisions, primarily in Title II and Title IV, prohibit restrictions among Member States while permitting limited derogations, aiming to eliminate barriers to economic exchange and mobility.[31] Implementation relies on secondary legislation, such as directives, and enforcement through the Court of Justice of the EU, which has interpreted measures with "equivalent effect" broadly to include non-tariff barriers.[41] Free movement of goods is governed by Articles 28 to 37, establishing a customs union that bans customs duties on imports and exports between Member States (Articles 28 to 30) and prohibits quantitative restrictions on imports or exports, along with all measures having equivalent effect (Articles 34 and 35).[31] Article 36 provides exceptions for protections of public morality, public policy or security, human or animal health, plant health, national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value, or industrial and commercial property rights, provided such measures do not constitute arbitrary discrimination or disguised restrictions on trade.[31] Article 37 mandates adjustments to state monopolies of a commercial character to ensure non-discriminatory access to goods.[31] These rules extend to agricultural products via Article 38, subject to the common agricultural policy.[31] Free movement of persons encompasses workers, self-employed individuals, and service providers, with distinct provisions under Title IV. For workers, Article 45 guarantees freedom of movement and residence for employment purposes, prohibiting discrimination based on nationality in access to employment, remuneration, and working conditions, while allowing exclusions for public service posts involving the exercise of official authority (Article 45(4)).[31] Articles 46 to 48 enable directives for administrative simplification, approximation of laws, and coordination of social security systems to facilitate mobility without overlapping benefits.[31] Freedom of establishment under Articles 49 to 55 prohibits restrictions on nationals of one Member State from setting up businesses, agencies, branches, or subsidiaries in another, treating companies equivalently to nationals (Article 54), with exceptions for public policy, security, or health (Article 52) and exclusions for official authority activities (Article 51).[31] Free movement of services, outlined in Articles 56 to 62, bans restrictions on the freedom to provide or receive services across Member States for self-employed or employed providers not covered by establishment rules, defining services as typically temporary activities (Article 57).[31] Article 58 excludes wage-earning services and links certain financial services to capital movement liberalization, while Article 62 applies public policy, security, or health derogations proportionally, mirroring establishment exceptions.[31] These provisions apply non-discriminatorily to service recipients traveling to access services (Article 61).[31] Free movement of capital, regulated by Articles 63 to 66, prohibits all restrictions on the movement of capital and payments between Member States and with third countries, extending to investments, loans, and securities.[31] Article 65 permits non-arbitrary measures for taxation, prudential supervision, or public policy/security reasons, provided they do not undermine the provision's objectives, while Article 66 allows temporary safeguards for balance-of-payments crises or economic stability threats, subject to Council authorization.[31] Pre-Maastricht restrictions on third-country capital may persist under Article 64 until harmonized.[31]Competition policy, state aid control, and approximation of laws

Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) prohibits agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings, and concerted practices that have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction, or distortion of competition within the internal market, including direct or indirect price fixing, limiting production, or dividing markets.[42] Such prohibitions apply insofar as they may affect trade between Member States, with the European Commission empowered to investigate, issue decisions, and impose fines up to 10% of an undertaking's annual turnover for violations.[42] Article 102 complements this by banning abusive conduct by undertakings in a dominant position, such as imposing unfair purchase or selling prices, limiting production or markets to the prejudice of consumers, or applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions.[43] These rules, originally from the Treaty of Rome in 1957, form the core of EU antitrust enforcement, with the Commission handling cases under Regulation 1/2003, which decentralizes some application to national authorities while ensuring consistent interpretation.[44] Merger control, though implemented via Council Regulation 139/2004, derives from Article 103 TFEU, which requires the Commission to ensure application of competition rules and, where necessary, address concentrations that impede effective competition.[45] Article 106 addresses public undertakings and services of general economic interest, stipulating that Member States must neither enact nor maintain measures contrary to TFEU rules in applying such undertakings, with the Commission able to address distortions from special or exclusive rights.[46] Overall, Title VII Chapter 1 of Part Three TFEU establishes these mechanisms to promote a competitive internal market, with enforcement yielding over €28 billion in fines from 2010 to 2020 for cartel and abuse cases, primarily targeting sectors like chemicals, automotive, and technology.[44] State aid control, outlined in Articles 107 to 109 TFEU, prohibits any aid granted by a Member State or through state resources in any form that distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods, insofar as it affects trade between Member States.[47] This incompatibility with the internal market applies unless exempted under Article 107(2) for aid of a social character, disaster relief, or serious disturbances in Member State economies, or under Article 107(3) for horizontal objectives like regional development, environmental protection, or research and development.[47] Member States must notify the Commission in advance of granting potentially incompatible aid via Article 108(3), which conducts a preliminary assessment and, if needed, in-depth investigation; unlawful aid can be recovered with interest, as seen in over 300 recovery orders totaling €10 billion from 2015 to 2020.[48] The framework balances national fiscal autonomy with market integrity, with derogations requiring demonstration of positive effects outweighing distortions. Approximation of laws, governed by Chapter 3 of Title VII TFEU, enables the Union to harmonize divergent national provisions that obstruct the internal market's establishment and functioning, primarily through Article 114, which authorizes the European Parliament and Council to adopt measures using the ordinary legislative procedure on a qualified majority vote.[49] This provision targets laws, regulations, or administrative actions creating barriers to free movement, emphasizing codification of existing texts and standards without harmonizing measures affecting fundamental principles like pay, right of association, or contract of employment.[49] Article 115 provides for tax-related approximations but requires unanimity in the Council after consulting the Parliament, reflecting sensitivities in fiscal sovereignty.[50] Since the TFEU's entry into force on 1 December 2009, Article 114 has served as the legal basis for over 1,000 legislative acts annually in areas like product safety, data protection, and financial services, facilitating market integration while allowing Member States to maintain stricter standards under Article 114(4)-(5) for environmental or health protection, subject to Commission review.[49]Economic and Monetary Union: Eurozone rules and fiscal coordination

The Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) framework in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) mandates coordination of Member States' economic policies to support the Union's objectives, including sustainable growth, high employment, and price stability, while assigning the European Central Bank (ECB) exclusive responsibility for monetary policy in the euro area.[51] Article 119 TFEU requires Member States to regard their economic policies as a matter of common concern and coordinate them within the Council, with the eurozone—consisting of states using the euro as their currency—subject to a single monetary policy aimed at maintaining price stability over the medium term.[51] This structure reflects the causal linkage between relinquishing national monetary sovereignty and the need for fiscal discipline to prevent free-riding and moral hazard in a shared currency union without fiscal union.[52] Eurozone accession and ongoing rules emphasize convergence criteria under Article 140 TFEU and Protocol (No 13) on the convergence criteria, which prospective members must satisfy: an inflation rate not exceeding that of the three best-performing Member States by more than 1.5 percentage points; a government budgetary deficit not exceeding 3% of GDP (unless exceptions apply for one-off factors or cyclical conditions); gross government debt not exceeding 60% of GDP or approaching that level sufficiently; exchange rate stability within the exchange rate mechanism for at least two years without devaluation; and long-term interest rates not exceeding those of the three best-performing states by more than 2 percentage points.[51] These criteria, codified from the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, aim to ensure fiscal sustainability before adopting the euro, with the Council assessing compliance every two years and deciding on irrevocably fixing exchange rates.[52] Post-adoption, eurozone states remain bound by these fiscal reference values, reinforced by multilateral surveillance under Article 121 TFEU, requiring annual examination of economic divergence and policy alignment.[51] Fiscal coordination mechanisms operationalize these rules primarily through the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), a secondary law framework based on Articles 121 and 126 TFEU, comprising preventive and corrective arms to enforce sound public finances.[53] The preventive arm obliges eurozone Member States to submit annual stability programmes detailing medium-term budgetary objectives, targeting positions close to balance or in surplus to allow automatic stabilizers without breaching the 3% deficit threshold during downturns; deviations trigger recommendations for corrective action.[53] The corrective arm invokes the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) when a deficit exceeds 3% of GDP or debt surpasses 60% without adequate reduction (at least 1/20th annual progress toward 60%), leading to Council decisions on existence of excessiveness, required adjustments within six months, and potential sanctions such as non-interest-bearing deposits or fines up to 0.5% of GDP if unaddressed. [54] Enforcement has historically faced challenges, with EDPs initiated against 25 Member States since 2002 but few progressing to sanctions due to Council voting requirements and crisis suspensions—such as the general escape clause activated from 2020 to 2023 amid the COVID-19 pandemic and energy shocks, allowing deficits to exceed limits temporarily.[55] As of June 2025, approximately one-third of EU Member States, including larger economies, remain in breach of the deficit criterion, highlighting persistent implementation gaps despite procedural triggers.[56] A 2024 reform of the SGP, effective from 2025, introduces multi-year debt reduction plans tailored via the European Semester, retaining the 3% deficit and 60% debt anchors but allowing flexibility for investments in green and digital transitions, though critics argue it risks perpetuating high debt ratios without stricter automaticity.[57] The European Semester integrates these elements into an annual cycle: national medium-term fiscal-structural plans are reviewed, stability programmes assessed, and country-specific recommendations issued, culminating in Council adoption to foster ex-ante policy alignment.[58] This process, grounded in Article 121(3) TFEU, underscores the TFEU's emphasis on peer review over centralized fiscal authority, a design choice that has empirically correlated with uneven compliance amid divergent national incentives.[59]Sectoral and Social Policies

Agriculture, fisheries, and rural development

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) establishes a common agricultural policy (CAP) in Title III, Chapter 1, extending internal market rules to agricultural products listed in Annex I, such as those from soil cultivation, stockfarming, and first-stage processing.[3] Article 38(1) mandates that the Union define and implement this policy, accounting for fisheries' specific characteristics while integrating them into the broader framework.[3] The policy's objectives, outlined in Article 39(1), include increasing agricultural productivity through technical progress and rational production factors; ensuring a fair standard of living for the agricultural community by improving producer earnings; stabilizing markets; assuring supplies; and providing reasonable prices for consumers.[3] [60] These goals must consider agriculture's social structure, structural and natural disparities between regions, the need for gradual adjustments, and its broader economic role (Article 39(2)).[3] Mechanisms for the CAP include a common organization of agricultural markets under Article 40, achieved through uniform competition rules, coordination or replacement of national market organizations, and potentially a European-level organization.[3] This may involve regulating prices, providing production and marketing aids, managing storage, and stabilizing imports and exports, with non-discriminatory application across Member States.[3] Article 40(3) allows for the creation of agricultural guidance and guarantee funds to support these efforts.[3] Additional measures encompass coordinating vocational training, agricultural practices research, knowledge dissemination (with possible joint financing), and promoting consumption of certain products (Article 41).[3] Competition rules generally apply to production and trade, subject to derogations by the European Parliament and Council to align with CAP objectives, including authorized state aid for structurally or naturally disadvantaged enterprises or regional development programs (Article 42).[3] The Commission proposes CAP measures, including market organization implementations, while the European Parliament and Council adopt regulations via the ordinary legislative procedure; the Council decides on specific elements like prices, levies, and quotas by qualified majority (Article 43).[3] The common fisheries policy (CFP), integrated within Title III, Chapter 2, focuses on managing fishery products under the CAP umbrella, with Union intervention via market organizations, producer preferences, and special measures distinct from general agricultural provisions.[3] Article 38(1) extends internal market rules to fisheries while recognizing their unique traits, such as biological resource conservation, which constitutes an exclusive Union competence under Article 3(1)(d).[3] Provisions under Article 43(3) enable Council adoption of measures on fishing opportunities, aligning with broader CAP objectives like resource sustainability and market stability.[3] The CFP shares competence with Member States for aquaculture, inland fishing, and processing, emphasizing long-term environmental sustainability, science-based management, and equitable access to EU waters for Member State fleets.[61] [62] Rural development is embedded in the CAP as a complementary pillar, addressing structural adjustments and regional disparities per Article 39(2)(a), with support for enterprises in disadvantaged areas via authorized aids (Article 42).[3] It draws on cohesion policy under Title XVIII, where Article 175 prioritizes rural areas in economic and social development, financed through instruments like the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development.[3] This shared competence (Article 4(2)(d)) promotes productivity gains, infrastructure improvements, and diversification beyond farming to mitigate depopulation and enhance viability in rural economies.[63] The policy integrates CAP market measures with targeted programs for innovation, environmental protection, and generational renewal, implemented via Member State strategic plans under Union oversight.[63] Article 44 allows countervailing charges on imports disrupting competitive positions due to national organizations, indirectly safeguarding rural producers.[3]Transport, trans-European networks, industry, and research

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) establishes a common transport policy under Title VI (Articles 90–100), which applies to the internal market and seeks to eliminate discrimination on grounds of nationality or place of establishment affecting transport operations.[64] This policy mandates the European Parliament and the Council, acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, to lay down common rules applicable to international transport to or from Member States, or passing across more than one Member State, including measures to improve transport quality and safety.[65] The Commission is required to undertake studies on transport infrastructure needs and ensure coordination of transport services, while state aid for inland transport is deemed compatible with the internal market if used for coordination or reimbursing public service obligations.[66] Article 93 specifies that such aid aligns with EU rules when fulfilling these functions, reflecting a balance between competition and public service requirements in sectors like rail and inland waterways.[66] Trans-European networks, addressed in Articles 170–172, enable the Union to contribute to the establishment and development of interconnected infrastructures in transport, telecommunications, and energy sectors of common interest, with a focus on integrating national networks to support the internal market and economic/social cohesion.[67] The Parliament and Council, via the ordinary legislative procedure, establish guidelines for these networks, including priority projects, while the Commission implements specific actions and ensures financial instruments for their realization.[68] In transport specifically, the trans-European transport network (TEN-T) promotes multimodal infrastructure development, such as railways, roads, inland waterways, and maritime links, to facilitate efficient cross-border movement; this framework underpins investments in core and comprehensive networks, with revisions in 2021 emphasizing sustainability and digitalization through the Connecting Europe Facility.[69] Industrial policy under Title XVII (Article 173) requires the Union and Member States to ensure conditions necessary for the competitiveness of the Union's industry, including actions to speed up structural adjustments, encourage better exploitation of industrial potential especially through innovation and research, and foster an environment favorable to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).[70] The Commission must maintain close contacts with the industrial sector via consultations and dialogues, but the provision explicitly prohibits the use of harmonization measures under Article 114 for industrial policy objectives unless indispensable for internal market functioning, preserving Member State autonomy in non-market-distorting areas.[71] This horizontal approach integrates with other policies like competition and research to enhance productivity without direct regulatory overreach.[72] Research and technological development, governed by Title XIX (Articles 179–191), aim to strengthen the Union's scientific and technological bases by creating a European research area that facilitates free movement of researchers, knowledge, technology, and circulation of results, while encouraging enterprise participation particularly by SMEs.[73] The Parliament and Council adopt multiannual framework programs defining priorities and implementation, with a specific program for the period 2021–2027 (Horizon Europe) allocating €95.5 billion to support collaborative R&D, frontier research via the European Research Council, and innovation ecosystems.[74] Complementary actions include joint undertakings under Article 187 for public-private partnerships and dissemination of results under Article 188, emphasizing complementarity with Member State programs to avoid duplication and maximize impact on competitiveness and societal challenges.[75] These provisions enable EU-level funding for projects transcending national borders, such as the €16 billion allocated to the European Research Council in Horizon Europe.[76]Environment, energy, health, consumer protection, and social cohesion

The TFEU establishes Union policy on the environment under Title XX, aiming to preserve, protect, and improve environmental quality, safeguard human health, utilize natural resources prudently, and promote international measures against regional or global issues, including climate change.[3] This constitutes a shared competence between the Union and Member States, with policies pursued through the ordinary legislative procedure, though fiscal measures, town and country planning, and land use require unanimity in the Council.[3] Core principles include maintaining a high level of protection accounting for regional diversity, the precautionary principle, preventive action, rectification at source, and the polluter pays principle, while allowing Member States to impose stricter rules compatible with Treaty obligations.[3] Title XXI addresses energy policy, seeking to secure supply, enhance energy efficiency and renewables, interconnect networks, and foster market functioning alongside sustainability, all within the internal market framework and environmental considerations.[3] As a shared competence, it respects Member States' rights to choose their energy mix and supply structures, with decisions generally via the ordinary legislative procedure but unanimity for fiscal aspects.[3] Public health provisions in Title XIV prioritize a high level of protection integrated across all Union policies, combating major scourges, promoting health information, preventing diseases, and addressing drug-related harms without harmonizing Member States' laws or service organizations.[3] This supporting competence involves coordination and incentives, using the ordinary legislative procedure for safety measures on products like medicines, while respecting national responsibilities.[3] Consumer protection, per Article 169, contributes to safeguarding health, safety, and economic interests through information, education, and representation rights, complementing national laws via the ordinary legislative procedure and integration into broader policies.[3][77] Economic and social cohesion under Title XVIII targets reducing regional disparities, particularly in less-developed, rural, or transitioning areas, to foster balanced growth through Structural Funds and the Cohesion Fund, implemented via multiannual programs and the ordinary legislative procedure.[3] This shared competence emphasizes solidarity, with the Union pursuing harmonious development while allowing special measures by unanimity.[3]Justice, Security, and Internal Affairs

Area of Freedom, Security and Justice: Borders, asylum, and immigration

The policies on border checks, asylum, and immigration are outlined in Chapter II of Title V of the TFEU, which empowers the Union to establish a coordinated framework while respecting Member State competences. Article 77 mandates the development of a policy to eliminate controls on persons crossing internal borders, irrespective of nationality, while ensuring effective checks and monitoring at external borders, alongside the gradual establishment of an integrated management system for those external borders.[78] This includes legislative measures adopted via the ordinary legislative procedure on common visa policies, short-stay residence permits, external border crossing conditions, and freedom of travel for third-country nationals within the Union for short periods.[78] Member States retain authority over the geographical demarcation of their borders in line with international law.[78] These border provisions underpin the Schengen Area, where internal border controls have been abolished among participating states since the implementation of the Schengen Agreement's acquis, integrated into EU law by the 1997 Amsterdam Treaty and further codified in the Schengen Borders Code (Regulation (EU) 2016/399), which standardizes external border checks and reintroduction of internal controls in exceptional cases, such as threats to public policy or security.[79] As of 2025, 27 EU Member States plus associated non-EU countries like Norway and Switzerland participate in Schengen, though Ireland maintains an opt-out and Cyprus has yet to fully join due to territorial issues. External border management has involved tools like the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), established in 2004 and reinforced in 2019 to conduct joint operations and rapid interventions, addressing irregular crossings that peaked at over 1 million detections in 2015 but declined to around 380,000 by 2023 amid enhanced controls.[80] On asylum, Article 78 requires a common policy offering appropriate status to third-country nationals requiring international protection, in accordance with the 1951 Geneva Convention and its 1967 Protocol, encompassing asylum, subsidiary protection, and temporary protection.[81] The ordinary legislative procedure applies to uniform status definitions, common procedures for granting and withdrawing protection, criteria determining Member State responsibility for examining applications, standards for reception conditions, and enhanced cooperation with third countries.[81] In cases of sudden inflows causing serious instability, the Council may adopt provisional measures on a Commission proposal, after consulting the European Parliament.[81] This framework implements the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), with key instruments including the Dublin IV Regulation (effective from 2026 under the 2024 Pact on Migration and Asylum), which allocates responsibility primarily to the first entry state, and the Asylum Procedures Regulation, mandating accelerated border procedures for certain claims to deter unfounded applications.[82] Empirical data indicate persistent imbalances, with Greece, Italy, and Spain handling disproportionate shares—over 50% of EU asylum applications in 2023—despite relocation efforts under Article 80's solidarity principle, which requires fair sharing of responsibilities including financial burdens but has yielded limited voluntary relocations historically.[83] Immigration policy under Article 79 focuses on efficient management of migration flows, fair treatment of legally residing third-country nationals, and prevention of illegal immigration and human trafficking.[84] Measures via ordinary legislative procedure cover conditions for entry and residence, including long-term visas, residence permits, and family reunification; rights enhancing freedom of movement for legal residents across Member States; actions against unauthorized residence, removal, and repatriation; and combating trafficking, particularly of women and children.[84] The Union may negotiate readmission agreements with third countries to facilitate returns, and non-harmonizing measures can promote integration.[84] Critically, Member States exclusively determine volumes of admission for third-country nationals as workers, preserving national sovereignty over labor migration.[84] Directives such as the 2003/86/EC Family Reunification Directive and the 2011/98/EU Single Permit Directive operationalize these, though enforcement varies, with return rates for irregular migrants averaging below 25% in recent years due to logistical and diplomatic challenges.[85][86] The 2024 Pact introduces mandatory border screening and solidarity mechanisms like relocation or financial contributions to alleviate pressure on frontline states.[87] Article 80 embeds these policies in a principle of solidarity and fair sharing of responsibilities among Member States, with Union measures incorporating appropriate enforcement tools where needed, though practical application has revealed tensions, as evidenced by legal disputes over mandatory quotas rejected by the Court of Justice in 2020 for lacking sufficient urgency under emergency provisions.[88][89] Denmark, Ireland, and historically the UK exercise opt-outs from Title V, limiting full AFSJ participation.[90]Judicial and police cooperation in criminal matters

Judicial cooperation in criminal matters under the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is outlined in Chapter 4 of Title V (Articles 82–86), emphasizing the principle of mutual recognition of judgments and judicial decisions to combat crime effectively across member states.[91] This framework aims to establish minimum rules on the rights of individuals in criminal proceedings and, where necessary, approximate member states' laws to facilitate such recognition, targeting offenses with a cross-border dimension like terrorism, trafficking in human beings, drug trafficking, and cybercrime.[91] Article 82(2) TFEU specifies directives for harmonizing procedural rights, including interpretation and translation, access to legal aid, and protections for vulnerable suspects.[91] Article 83 TFEU authorizes the adoption of directives to establish minimum rules on the definition of criminal offenses and sanctions for serious cross-border crimes, either through approximation of laws or the European Public Prosecutor's Office (EPPO), while respecting principles of proportionality and subsidiarity.[92] This includes Framework Decisions or Directives for categories such as organized crime, corruption, and money laundering, with the ordinary legislative procedure applying post-Lisbon Treaty amendments effective December 1, 2009.[92] Article 84 TFEU enables non-harmonizing measures to promote crime prevention, such as supporting member states' actions and facilitating cooperation among judicial authorities, without compelling legislative approximation.[93] Eurojust, established under Article 85 TFEU, coordinates investigations and prosecutions involving multiple member states, with powers to initiate proceedings, propose prosecutions, and monitor compliance with EU law in criminal matters.[94] Regulations governing Eurojust are adopted by the Council after consulting the European Parliament, ensuring operational independence while fostering cooperation with national authorities and bodies like Europol.[94] Article 86 TFEU provides for the EPPO to investigate and prosecute crimes against the EU's financial interests, operational since June 1, 2021, in participating member states, with enhanced powers via unanimous Council decision or enhanced cooperation.[95] Police cooperation is regulated in Chapter 5 of Title V (Articles 87–89), mandating the Union to establish mechanisms involving member states' competent authorities, including police and customs, to prevent and combat serious forms of organized crime, terrorism, and illegal drug trafficking.[96] Article 87(2) TFEU outlines measures such as information exchange, common risk analyses, specialized training, and non-operational cooperation, adopted via ordinary legislative procedure, while paragraph 3 allows for operational measures like joint threat assessments under Council framework decisions.[96] Europol, per Article 88 TFEU, supports cross-border policing through a central office for collecting, storing, and analyzing information on serious crimes, with regulations specifying its structure, operations, and data-processing rules to ensure data protection compliance.[97] Established in 1999 and reformed post-Lisbon, Europol facilitates operational coordination but lacks direct enforcement powers, relying on national authorities.[97] Article 89 TFEU permits common rules on operational police cooperation across borders, including setting up specialized units or the EPPO's exercise of powers, subject to unanimity in the Council unless via enhanced cooperation mechanisms.[98] These provisions apply to all member states except those exercising opt-outs, such as Denmark for Title V matters, with transitional arrangements for others like Ireland.[96]Protection of fundamental rights and data privacy

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) integrates the protection of fundamental rights into its framework for the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (AFSJ), outlined in Title V. Article 67(1) TFEU requires that the Union establish an AFSJ "with respect for fundamental rights and the different legal systems and traditions of the Member States," emphasizing mutual recognition of judgments and cooperation while safeguarding rights such as fair trial guarantees under Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights.[99] This provision binds EU institutions and Member States when implementing EU law, with the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) empowered to review compliance, as seen in cases invalidating measures that infringe rights like data protection in cross-border exchanges.[100] Fundamental rights enforcement in the AFSJ draws from the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which acquired binding force equivalent to the Treaties upon the Lisbon Treaty's entry into force on December 1, 2009, applying to EU actions and Member State measures transposing EU law.[101] Specific AFSJ chapters, such as those on judicial cooperation in criminal matters (Articles 82–86 TFEU), mandate respect for rights including non-discrimination (Article 21 Charter) and the principle of proportionality in directives like the European Arrest Warrant framework, which the CJEU has struck down elements of when they undermine defense rights.[99] Data privacy intersects here through safeguards in systems like the Schengen Information System and Europol data processing, where Article 16 TFEU's mandate for uniform protection rules limits unrestricted sharing to prevent rights erosions.[102] Article 16 TFEU explicitly enshrines data protection as a standalone right: "Everyone has the right to the protection of personal data concerning them," with Union institutions required to adopt regulations ensuring this, forming the basis for the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) adopted on April 27, 2016, under the ordinary legislative procedure.[103] This article, located in Title II on general provisions, empowers the European Parliament and Council to legislate harmonized rules applicable Union-wide, including in AFSJ contexts like police cooperation (Article 87 TFEU), where data exchanges must comply with necessity and proportionality tests to avoid mass surveillance overreach.[104] The CJEU has upheld this by fining entities for violations, such as in the 2020 Schrems II ruling annulling the EU-US Privacy Shield for inadequate safeguards against foreign government access.[105] In practice, TFEU data privacy provisions balance security imperatives with rights, as Article 16(2) TFEU delegates rulemaking to ensure individuals' access and rectification rights, evidenced by over 1,200 CJEU data protection rulings since 2016 enforcing limits on automated processing in justice matters.[106] However, empirical critiques highlight enforcement gaps, with Member States like Hungary facing infringement proceedings in 2023 for national laws diluting GDPR independence via under-resourced authorities.[107] These mechanisms underscore causal tensions: enhanced AFSJ data flows enable crime-fighting efficiency but risk rights dilution without rigorous CJEU oversight.[108]External Relations and Policies

Common commercial policy and trade agreements

The common commercial policy (CCP) of the European Union, as codified in Articles 206 and 207 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), establishes uniform principles for external trade relations, including tariff rates with third countries, trade agreements, export policy, measures against dumping and subsidies, and quantitative restrictions on imports and exports.[109] This policy aims to contribute, in the context of the World Trade Organization (WTO), to the harmonious development of world trade, the progressive abolition of restrictions on international trade, and the protection of essential interests as determined by EU institutions.[110] The Lisbon Treaty, effective December 1, 2009, designated the CCP as an exclusive EU competence, encompassing not only trade in goods but also services, the commercial aspects of intellectual property, and foreign direct investment, thereby preventing member states from acting unilaterally in these areas.[111][112] Under Article 207(3) TFEU, the European Commission conducts negotiations for trade agreements after receiving a mandate from the Council of the EU, which adopts directives specifying the objectives and scope.[113] The Council then approves the signing and conclusion of agreements by qualified majority voting, while the European Parliament provides consent but lacks amendment powers, a process governed by Article 218(6) TFEU for international agreements.[114] Agreements falling partly outside exclusive competences—such as investor-state dispute settlement or non-trade issues—require "mixed" ratification, involving approval by national parliaments, which can delay implementation and highlight tensions between EU-level efficiency and national sovereignty.[115] This framework has enabled the EU to negotiate as a bloc, representing over 440 million consumers and achieving tariff reductions in sectors like agriculture and manufacturing, though critics argue it erodes member state control over trade-sensitive policies, such as agricultural protections, without sufficient direct democratic oversight.[116] The EU has concluded numerous free trade agreements (FTAs) under the CCP, with over 40 in force or provisionally applied as of 2025, covering approximately 70 countries and facilitating €2.3 trillion in annual trade.[117] Key examples include the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with Canada, provisionally applied since September 21, 2017, which eliminated 98% of tariffs and opened services markets; the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement, in force since February 1, 2019, reducing tariffs on 99% of goods; and the modernized EU-Chile Association Agreement, entering provisional application in 2025 after ratification.[117] Pending deals, such as the EU-Mercosur FTA signed in 2019 but unratified due to environmental and agricultural concerns from member states like France, underscore empirical challenges: while FTAs have boosted EU exports by an average 2-3% in covered sectors per World Bank estimates, they have faced opposition over standards alignment and potential job displacements in industries like automotive and farming.[118][117]| Agreement | Partner(s) | Status | Key Provisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CETA | Canada | Provisional (2017) | 98% tariff elimination; services liberalization[117] |

| EU-Japan EPA | Japan | In force (2019) | 99% tariff cuts; IP protection enhancements[117] |

| EU-Chile Modernized | Chile | Provisional (2025) | Updated tariffs; sustainable development chapters[117] |

| EU-Vietnam FTA | Vietnam | In force (2020) | 99% tariff removal over 7 years; rules of origin[117] |

Development cooperation, humanitarian aid, and economic partnerships