Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tachycardia

View on Wikipedia

| Tachycardia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Tachyarrhythmia |

| |

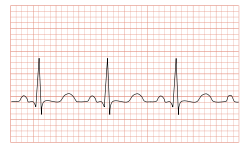

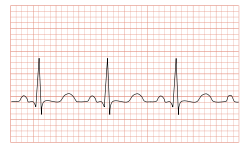

| ECG showing sinus tachycardia with a rate of about 100 beats per minute | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Differential diagnosis | |

Tachycardia, also called tachyarrhythmia, is a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate.[1] In general, a resting heart rate over 100 beats per minute is accepted as tachycardia in adults.[1] Heart rates above the resting rate may be normal (such as with exercise) or abnormal (such as with electrical problems within the heart).

Complications

[edit]Tachycardia can lead to fainting.[2]

When the rate of blood flow becomes too rapid, or fast blood flow passes on damaged endothelium, it increases the friction within vessels resulting in turbulence and other disturbances.[3] According to the Virchow's triad, this is one of the three conditions (along with hypercoagulability and endothelial injury/dysfunction) that can lead to thrombosis (i.e., blood clots within vessels).[4]

Causes

[edit]Some causes of tachycardia include:[5]

- Adrenergic storm

- Anaemia

- Anxiety

- Atrial fibrillation

- Atrial flutter

- Atrial tachycardia

- Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia

- AV nodal reentrant tachycardia

- Brugada syndrome

- Circulatory shock and its various causes (obstructive shock, cardiogenic shock, hypovolemic shock, distributive shock)

- Dehydration

- Dysautonomia

- Exercise

- Fear

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypovolemia

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hyperventilation

- Inappropriate sinus tachycardia

- Junctional tachycardia

- Metabolic myopathy

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia

- Pacemaker mediated

- Pain

- Panic attack

- Pheochromocytoma

- Sinus tachycardia

- Sleep deprivation[6]

- Supraventricular tachycardia

- Ventricular tachycardia

- Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

Drug related:

- Alcohol (ethanol) intoxication

- Stimulants

- Cannabis

- Drug withdrawal

- Tricyclic antidepressants

- Nefopam

- Opioids (rare)

Diagnosis

[edit]The upper threshold of a normal human resting heart rate is based on age. Cutoff values for tachycardia in different age groups are fairly well standardized; typical cutoffs are listed below:[7][8]

- 1–2 days: Tachycardia >159 beats per minute (bpm)

- 3–6 days: Tachycardia >166 bpm

- 1–3 weeks: Tachycardia >182 bpm

- 1–2 months: Tachycardia >179 bpm

- 3–5 months: Tachycardia >186 bpm

- 6–11 months: Tachycardia >169 bpm

- 1–2 years: Tachycardia >151 bpm

- 3–4 years: Tachycardia >137 bpm

- 5–7 years: Tachycardia >133 bpm

- 8–11 years: Tachycardia >130 bpm

- 12–15 years: Tachycardia >119 bpm

- >15 years – adult: Tachycardia >100 bpm

Heart rate is considered in the context of the prevailing clinical picture. When the heart beats excessively or rapidly, the heart pumps less efficiently and provides less blood flow to the rest of the body, including the heart itself. The increased heart rate also leads to increased work and oxygen demand by the heart, which can lead to rate related ischemia.[9]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is used to classify the type of tachycardia. They may be classified into narrow and wide complex based on the QRS complex.[10] Equal or less than 0.1s for narrow complex.[11] Presented in order of most to least common, they are:[10]

- Narrow complex

- Sinus tachycardia, which originates from the sino-atrial (SA) node, near the base of the superior vena cava

- Atrial fibrillation

- Atrial flutter

- AV nodal reentrant tachycardia

- Accessory pathway mediated tachycardia

- Atrial tachycardia

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia

- Cardiac tamponade

- Junctional tachycardia (rare in adults)

- Wide complex

- Ventricular tachycardia, any tachycardia that originates in the ventricles

- Any narrow complex tachycardia combined with a problem with the conduction system of the heart, often termed "supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy"

- A narrow complex tachycardia with an accessory conduction pathway, often termed "supraventricular tachycardia with pre-excitation" (e.g. Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome)

- Pacemaker-tracked or pacemaker-mediated tachycardia

Tachycardias may be classified as either narrow complex tachycardias (supraventricular tachycardias) or wide complex tachycardias. Narrow and wide refer to the width of the QRS complex on the ECG. Narrow complex tachycardias tend to originate in the atria, while wide complex tachycardias tend to originate in the ventricles. Tachycardias can be further classified as either regular or irregular.[citation needed]

Sinus

[edit]

The body has several feedback mechanisms to maintain adequate blood flow and blood pressure. If blood pressure decreases, the heart beats faster in an attempt to raise it. This is called reflex tachycardia. This can happen in response to a decrease in blood volume (through dehydration or bleeding), or an unexpected change in blood flow. The most common cause of the latter is orthostatic hypotension (also called postural hypotension). Fever, hyperventilation, diarrhea and severe infections can also cause tachycardia, primarily due to increase in metabolic demands.[citation needed]

Upon exertion, sinus tachycardia can also be seen in some inborn errors of metabolism that result in metabolic myopathies, such as McArdle's disease (GSD-V).[12][13] Metabolic myopathies interfere with the muscle's ability to create energy. This energy shortage in muscle cells causes an inappropriate rapid heart rate in response to exercise. The heart tries to compensate for the energy shortage by increasing heart rate to maximize delivery of oxygen and other blood borne fuels to the muscle cells.[12]

"In McArdle's, our heart rate tends to increase in what is called an 'inappropriate' response. That is, after the start of exercise it increases much more quickly than would be expected in someone unaffected by McArdle's."[14] As skeletal muscle relies predominantly on glycogenolysis for the first few minutes as it transitions from rest to activity, as well as throughout high-intensity aerobic activity and all anaerobic activity, individuals with GSD-V experience during exercise: sinus tachycardia, tachypnea, muscle fatigue and pain, during the aforementioned activities and time frames.[12][13] Those with GSD-V also experience "second wind", after approximately 6–10 minutes of light-moderate aerobic activity, such as walking without an incline, where the heart rate drops and symptoms of exercise intolerance improve.[12][13][14]

An increase in sympathetic nervous system stimulation causes the heart rate to increase, both by the direct action of sympathetic nerve fibers on the heart and by causing the endocrine system to release hormones such as epinephrine (adrenaline), which have a similar effect. Increased sympathetic stimulation is usually due to physical or psychological stress. This is the basis for the so-called fight-or-flight response, but such stimulation can also be induced by stimulants such as ephedrine, amphetamines or cocaine. Certain endocrine disorders such as pheochromocytoma can also cause epinephrine release and can result in tachycardia independent of nervous system stimulation. Hyperthyroidism can also cause tachycardia.[15] The upper limit of normal rate for sinus tachycardia is thought to be 220 bpm minus age.[citation needed]

Inappropriate sinus tachycardia

[edit]Inappropriate sinus tachycardia (IST) is a diagnosis of exclusion,[16] a rare but benign type of cardiac arrhythmia that may be caused by a structural abnormality in the sinus node. It can occur in seemingly healthy individuals with no history of cardiovascular disease. Other causes may include autonomic nervous system deficits, autoimmune response, or drug interactions. Although symptoms might be distressing, treatment is not generally needed.[17]

Ventricular

[edit]Ventricular tachycardia (VT or V-tach) is a potentially life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia that originates in the ventricles. It is usually a regular, wide complex tachycardia with a rate between 120 and 250 beats per minute. A medically significant subvariant of ventricular tachycardia is called torsades de pointes (literally meaning "twisting of the points", due to its appearance on an EKG), which tends to result from a long QT interval.[18]

Both of these rhythms normally last for only a few seconds to minutes (paroxysmal tachycardia), but if VT persists it is extremely dangerous, often leading to ventricular fibrillation.[19][20]

Supraventricular

[edit]This is a type of tachycardia that originates from above the ventricles, such as the atria. It is sometimes known as paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (PAT). Several types of supraventricular tachycardia are known to exist.[21]

Atrial fibrillation

[edit]Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common cardiac arrhythmias. In general, it is an irregular, narrow complex rhythm. However, it may show wide QRS complexes on the ECG if a bundle branch block is present. At high rates, the QRS complex may also become wide due to the Ashman phenomenon. It may be difficult to determine the rhythm's regularity when the rate exceeds 150 beats per minute. Depending on the patient's health and other variables such as medications taken for rate control, atrial fibrillation may cause heart rates that span from 50 to 250 beats per minute (or even higher if an accessory pathway is present). However, new-onset atrial fibrillation tends to present with rates between 100 and 150 beats per minute.[22]

AV nodal reentrant tachycardia

[edit]AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) is the most common reentrant tachycardia. It is a regular narrow complex tachycardia that usually responds well to the Valsalva maneuver or the drug adenosine. However, unstable patients sometimes require synchronized cardioversion. Definitive care may include catheter ablation.[23]

AV reentrant tachycardia

[edit]AV reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) requires an accessory pathway for its maintenance. AVRT may involve orthodromic conduction (where the impulse travels down the AV node to the ventricles and back up to the atria through the accessory pathway) or antidromic conduction (which the impulse travels down the accessory pathway and back up to the atria through the AV node). Orthodromic conduction usually results in a narrow complex tachycardia, and antidromic conduction usually results in a wide complex tachycardia that often mimics ventricular tachycardia. Most antiarrhythmics are contraindicated in the emergency treatment of AVRT, because they may paradoxically increase conduction across the accessory pathway. [citation needed]

Junctional tachycardia

[edit]Junctional tachycardia is an automatic tachycardia originating in the AV junction. It tends to be a regular, narrow complex tachycardia and may be a sign of digitalis toxicity.[24]

Management

[edit]The management of tachycardia depends on its type (wide complex versus narrow complex), whether or not the person is stable or unstable, and whether the instability is due to the tachycardia.[10] Unstable means that either important organ functions are affected or cardiac arrest is about to occur.[10] Stable means that there is a tachycardia, but it does not seem an immediate threat for the patient's health, but only a symptom of an unknown disease, or a reaction that is not very dangerous in that moment.

Unstable

[edit]In those that are unstable with a narrow complex tachycardia, intravenous adenosine may be attempted.[10] In all others, immediate cardioversion is recommended.[10]

Stable

[edit]If the problem is a simple acceleration of the heart rate that worries the patient, but the heart and the general patient's health remain stable enough, it is possible to correct it by a simple deceleration using physical maneuvers called vagal maneuvers.[25] But, if the cause of the tachycardia is chronic (permanent), it would return after some time, unless that cause is corrected.

Besides, the patient should avoid receiving external effects that cause or increase tachycardia.

The same measures as in unstable tachycardia can also be taken, with medications and the type of cardioversion that is appropriate for the patient's tachycardia.[10]

Terminology

[edit]The word tachycardia came to English from Neo-Latin as a neoclassical compound built from the combining forms tachy- + -cardia, which are from the Greek ταχύς tachys, "quick, rapid" and καρδία, kardia, "heart". As a matter both of usage choices in the medical literature and of idiom in natural language, the words tachycardia and tachyarrhythmia are usually used interchangeably, or loosely enough that precise differentiation is not explicit. Some careful writers have tried to maintain a logical differentiation between them, which is reflected in major medical dictionaries[26][27][28] and major general dictionaries.[29][30][31] The distinction is that tachycardia be reserved for the rapid heart rate itself, regardless of cause, physiologic or pathologic (that is, from healthy response to exercise or from cardiac arrhythmia), and that tachyarrhythmia be reserved for the pathologic form (that is, an arrhythmia of the rapid rate type). This is why five of the previously referenced dictionaries do not enter cross-references indicating synonymy between their entries for the two words (as they do elsewhere whenever synonymy is meant), and it is why one of them explicitly specifies that the two words not be confused.[28] But the prescription will probably never be successfully imposed on general usage, not only because much of the existing medical literature ignores it even when the words stand alone but also because the terms for specific types of arrhythmia (standard collocations of adjectives and noun) are deeply established idiomatically with the tachycardia version as the more commonly used version. Thus SVT is called supraventricular tachycardia more than twice as often as it is called supraventricular tachyarrhythmia; moreover, those two terms are always completely synonymous—in natural language there is no such term as "healthy/physiologic supraventricular tachycardia". The same themes are also true of AVRT and AVNRT. Thus this pair is an example of when a particular prescription (which may have been tenable 50 or 100 years earlier) can no longer be invariably enforced without violating idiom. But the power to differentiate in an idiomatic way is not lost, regardless, because when the specification of physiologic tachycardia is needed, that phrase aptly conveys it.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Awtry EH, Jeon C, Ware MG (2006). "Tachyarrhythmias". Blueprints Cardiology (2nd ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. p. 93. ISBN 9781405104647.

- ^ Thompson EG, Pai RK, eds. (2 June 2011). "Passing Out (Syncope) Caused by Arrhythmias". CardioSmart. American College of Cardiology. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Kushner A, West WP, Pillarisetty LS (2020). "Virchow Triad". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30969519. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Kumar DR, Hanlin E, Glurich I, Mazza JJ, Yale SH (December 2010). "Virchow's contribution to the understanding of thrombosis and cellular biology". Clinical Medicine & Research. 8 (3–4): 168–172. doi:10.3121/cmr.2009.866. PMC 3006583. PMID 20739582.

- ^ "Supraventricular Tachycardias". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Rangaraj VR, Knutson KL (February 2016). "Association between sleep deficiency and cardiometabolic disease: implications for health disparities". Sleep Medicine. 18: 19–35. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.535. PMC 4758899. PMID 26431758.

- ^ Custer JW, Rau RE, Budzikowski AS, Cho CS (2008). Rottman JN (ed.). The Harriet Lane Handbook (18th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-07688-3.

- ^ Kantharia BK, Sharma M, Shah AN (17 October 2021). "Atrial Tachycardia: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy". MedScape. WebMD LLC.

- ^ Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J (2008). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-146633-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. (November 2010). "Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S729 – S767. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. PMID 20956224.

- ^ Pieper SJ, Stanton MS (April 1995). "Narrow QRS complex tachycardias". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 70 (4): 371–375. doi:10.4065/70.4.371. PMID 7898144.

- ^ a b c d Lucia A, Martinuzzi A, Nogales-Gadea G, Quinlivan R, Reason S (December 2021). "Clinical practice guidelines for glycogen storage disease V & VII (McArdle disease and Tarui disease) from an international study group". Neuromuscular Disorders. 31 (12): 1296–1310. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2021.10.006. hdl:11268/11047. PMID 34848128.

- ^ a b c Scalco RS, Chatfield S, Godfrey R, Pattni J, Ellerton C, Beggs A, Brady S, Wakelin A, Holton JL, Quinlivan R (July 2014). "From exercise intolerance to functional improvement: the second wind phenomenon in the identification of McArdle disease". Arquivos de Neuro-psiquiatria. 72 (7): 538–41. doi:10.1590/0004-282x20140062. PMID 25054987.

- ^ a b Wakelin A (2017). Living With McArdle Disease (PDF). International Assoc. of Muscle Glycogen Diseases (IAMGSD). p. 15.

- ^ Barker RL, Burton JR, Zieve PD, eds. (2003). Principles of Ambulatory Medicine (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippinocott, Wilkins & Williams. ISBN 0-7817-3486-X.

- ^ Ahmed A, Pothineni NV, Charate R, Garg J, Elbey M, de Asmundis C, LaMeir M, Romeya A, Shivamurthy P, Olshansky B, Russo A, Gopinathannair R, Lakkireddy D (21 June 2022). "Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Management: JACC Review Topic of the Week". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 79 (24): 2450–2462. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.019. ISSN 0735-1097. PMID 35710196.

- ^ Peyrol M, Lévy S (June 2016). "Clinical presentation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia and differential diagnosis". Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology. 46 (1): 33–41. doi:10.1007/s10840-015-0051-z. PMID 26329720. S2CID 23249973.

- ^ Mitchell LB (January 2023). "Torsades de Pointes Ventricular Tachycardia". Merck Manual Profesional Edition. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ Samie FH, Jalife J (May 2001). "Mechanisms underlying ventricular tachycardia and its transition to ventricular fibrillation in the structurally normal heart". Cardiovascular Research. 50 (2): 242–250. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00289-3. PMID 11334828.

- ^ Srivathsan K, Ng DW, Mookadam F (July 2009). "Ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation". Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 7 (7): 801–809. doi:10.1586/erc.09.69. PMID 19589116. S2CID 207215117.

- ^ "Types of Arrhythmia". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). U.S. National Institutes of Health. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015.

- ^ Oiseth S, Jones L, Maza E (11 August 2020). "Atrial Fibrillation". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Katritsis DG (December 2018). "Catheter Ablation of Atrioventricular Nodal Re-entrant Tachycardia: Facts and Fiction". Arrhythmia & Electrophysiology Review. 7 (4): 230–231. doi:10.15420/aer.2018.7.4.EO1. PMC 6304791. PMID 30588309.

- ^ Rosen KM (March 1973). "Junctional tachycardia. Mechanisms, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and management". Circulation. 47 (3): 654–664. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.47.3.654. PMID 4571060.

- ^ Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, Calkins H, Conti JB, Deal BJ, Estes NM, Field ME, Goldberger ZD, Hammill SC, Indik JH, Lindsay BD, Olshansky B, Russo AM, Shen WK (5 April 2016). "2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 133 (14). doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000311. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ^ Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier.

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b Wolters Kluwer, Stedman's Medical Dictionary, Wolters Kluwer.

- ^ Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, archived from the original on 10 October 2020, retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Unabridged Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, archived from the original on 25 May 2020, retrieved 22 July 2017.