Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Metabolism

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Biochemistry |

|---|

|

Metabolism (/məˈtæbəlɪzəm/, from Greek: μεταβολή metabolē, "change") refers to the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions that occur within living organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are the conversion of energy in food into a usable form for cellular processes; the conversion of food to building blocks of macromolecules (biopolymers) such as proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and some carbohydrates; and the excretion of metabolic wastes. These enzyme-catalyzed reactions allow organisms to grow, reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. The word metabolism can also refer to all chemical reactions that occur in living organisms, including digestion and the transportation of substances into and between different cells. In a broader sense, the set of reactions occurring within the cells is called intermediary (or intermediate) metabolism.

Metabolic reactions may be categorized as catabolic—the breaking down of compounds (for example, of glucose to pyruvate by cellular respiration); or anabolic—the building up (biosynthesis) of compounds (such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids). Usually, catabolism releases energy, and anabolism consumes energy.

The chemical reactions of metabolism are organized into metabolic pathways, in which one chemical is transformed through a series of steps into another chemical, each step being facilitated by a specific enzyme. Enzymes are crucial to metabolism because they allow organisms to drive desirable reactions that require energy and will not occur by themselves, by coupling them to spontaneous reactions that release energy. Enzymes act as catalysts—they allow a reaction to proceed more rapidly—and they also allow the regulation of the rate of a metabolic reaction, for example in response to changes in the cell's environment or to signals from other cells.

The metabolic system of a particular organism determines which substances it will find nutritious and which poisonous. For example, some prokaryotes use hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) as a nutrient, yet this gas is poisonous to some animals.[1] Since hydrogen sulfide is a gasotransmitter, certain mammals including humans produce H₂S naturally in very small concentrations where it serves vital signaling and regulatory functions.[2] The basal metabolic rate of an organism is the measure of the amount of energy consumed by all of these chemical reactions.

A striking feature of metabolism is the similarity of the basic metabolic pathways among vastly different species.[3] For example, the set of carboxylic acids that are best known as the intermediates in the citric acid cycle are present in all known organisms, being found in species as diverse as the unicellular bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli) and huge multicellular organisms like elephants.[4] These similarities in metabolic pathways are likely due to their early appearance in evolutionary history, and their retention is likely due to their efficacy.[5][6] In various diseases, such as type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cancer, normal metabolism is disrupted.[7] The metabolism of cancer cells is also different from the metabolism of normal cells, and these differences can be used to find targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer.[8]

Key biochemicals

[edit]Most of the structures that make up animals, plants and microbes are made from four basic classes of molecules: amino acids, carbohydrates, nucleic acid and lipids (often called fats). As these molecules are vital for life, metabolic reactions either focus on making these molecules during the construction of cells and tissues, or on breaking them down and using them to obtain energy, by their digestion. These biochemicals can be joined to make polymers such as DNA and proteins, essential macromolecules of life.[9]

| Type of molecule | Name of monomer forms | Name of polymer forms | Examples of polymer forms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | Amino acids | Proteins (made of polypeptides) | Fibrous proteins and globular proteins |

| Carbohydrates | Monosaccharides | Polysaccharides | Starch, glycogen and cellulose |

| Nucleic acids | Nucleotides | Polynucleotides | DNA and RNA |

Amino acids and proteins

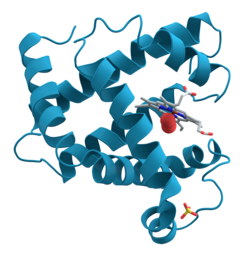

[edit]Proteins are made of amino acids arranged in a linear chain joined by peptide bonds. Many proteins are enzymes that catalyze the chemical reactions in metabolism. Other proteins have structural or mechanical functions, such as those that form the cytoskeleton, a system of scaffolding that maintains the cell shape.[10] Proteins are also important in cell signaling, immune responses, cell adhesion, active transport across membranes, and the cell cycle.[11] Amino acids also contribute to cellular energy metabolism by providing a carbon source for entry into the citric acid cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle),[12] especially when a primary source of energy, such as glucose, is scarce, or when cells undergo metabolic stress.[13]

Lipids

[edit]Lipids are the most diverse group of biochemicals. Their main structural uses are as part of internal and external biological membranes such as the cell membrane.[11] Their chemical energy can also be used. Lipids contain a long, non-polar hydrocarbon chain with a small polar region containing oxygen. Lipids are usually defined as hydrophobic or amphipathic biological molecules but will dissolve in organic solvents such as ethanol, benzene or chloroform.[14] The fats are a large group of compounds that contain fatty acids and glycerol; a glycerol molecule attached to three fatty acids by ester linkages is called a triacylglyceride.[15] Several variations of the basic structure exist, including backbones such as sphingosine in sphingomyelin, and hydrophilic groups such as phosphate in phospholipids. Steroids such as sterol are another major class of lipids.[16]

Carbohydrates

[edit]

Carbohydrates are aldehydes or ketones, with many hydroxyl groups attached, that can exist as straight chains or rings. Carbohydrates are the most abundant biological molecules, and fill numerous roles, such as the storage and transport of energy (starch, glycogen) and structural components (cellulose in plants, chitin in animals).[11] The basic carbohydrate units are called monosaccharides and include galactose, fructose, and most importantly glucose. Monosaccharides can be linked together to form polysaccharides in almost limitless ways.[17]

Nucleotides

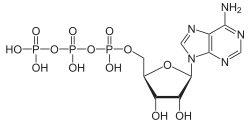

[edit]The two nucleic acids, DNA and RNA, are polymers of nucleotides. Each nucleotide is composed of a phosphate attached to a ribose or deoxyribose sugar group which is attached to a nitrogenous base. Nucleic acids are critical for the storage and use of genetic information, and its interpretation through the processes of transcription and protein biosynthesis.[11] This information is protected by DNA repair mechanisms and propagated through DNA replication. Many viruses have an RNA genome, such as HIV, which uses reverse transcription to create a DNA template from its viral RNA genome.[18] RNA in ribozymes such as spliceosomes and ribosomes is similar to enzymes as it can catalyze chemical reactions. Individual nucleosides are made by attaching a nucleobase to a ribose sugar. These bases are heterocyclic rings containing nitrogen, classified as purines or pyrimidines. Nucleotides also act as coenzymes in metabolic-group-transfer reactions.[19]

Coenzymes

[edit]

Metabolism involves a vast array of chemical reactions, but most fall under a few basic types of reactions that involve the transfer of functional groups of atoms and their bonds within molecules.[20] This common chemistry allows cells to use a small set of metabolic intermediates to carry chemical groups between different reactions.[19] These group-transfer intermediates are called coenzymes. Each class of group-transfer reactions is carried out by a particular coenzyme, which is the substrate for a set of enzymes that produce it, and a set of enzymes that consume it. These coenzymes are therefore continuously made, consumed and then recycled.[21]

One central coenzyme is adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which is the energy currency of cells. This nucleotide is used to transfer chemical energy between different chemical reactions. There is only a small amount of ATP in cells, but as it is continuously regenerated, the human body can use about its own weight in ATP per day.[21] ATP acts as a bridge between catabolism and anabolism. Catabolism breaks down molecules, and anabolism puts them together. Catabolic reactions generate ATP, and anabolic reactions consume it. It also serves as a carrier of phosphate groups in phosphorylation reactions.[22]

A vitamin is an organic compound needed in small quantities that cannot be made in cells. In human nutrition, most vitamins function as coenzymes after modification; for example, all water-soluble vitamins are phosphorylated or are coupled to nucleotides when they are used in cells.[23] Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), a derivative of vitamin B3 (niacin), is an important coenzyme that acts as a hydrogen acceptor. Hundreds of separate types of dehydrogenases remove electrons from their substrates and reduce NAD+ into NADH. This reduced form of the coenzyme is then a substrate for any of the reductases in the cell that need to transfer hydrogen atoms to their substrates.[24] Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide exists in two related forms in the cell, NADH and NADPH. The NAD+/NADH form is more important in catabolic reactions, while NADP+/NADPH is used in anabolic reactions.[25]

Minerals and cofactors

[edit]Inorganic elements play critical roles in metabolism; some are abundant (e.g. sodium and potassium) while others function at minute concentrations. About 99% of a human's body weight is made up of the elements carbon, nitrogen, calcium, sodium, chlorine, potassium, hydrogen, phosphorus, oxygen and sulfur. Organic compounds (proteins, lipids and carbohydrates) contain the majority of the carbon and nitrogen; most of the oxygen and hydrogen is present as water.[26]

The abundant inorganic elements act as electrolytes. The most important ions are sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, phosphate and the organic ion bicarbonate. The maintenance of precise ion gradients across cell membranes maintains osmotic pressure and pH.[27] Ions are also critical for nerve and muscle function, as action potentials in these tissues are produced by the exchange of electrolytes between the extracellular fluid and the cell's fluid, the cytosol.[28] Electrolytes enter and leave cells through proteins in the cell membrane called ion channels. For example, muscle contraction depends upon the movement of calcium, sodium and potassium through ion channels in the cell membrane and T-tubules.[29]

Transition metals are usually present as trace elements in organisms, with zinc and iron being most abundant of those.[30] Metal cofactors are bound tightly to specific sites in proteins; although enzyme cofactors can be modified during catalysis, they always return to their original state by the end of the reaction catalyzed. Metal micronutrients are taken up into organisms by specific transporters and bind to storage proteins such as ferritin or metallothionein when not in use.[31][32]

Catabolism

[edit]Catabolism is the set of metabolic processes that break down large molecules. These include breaking down and oxidizing food molecules. The purpose of the catabolic reactions is to provide the energy and components needed by anabolic reactions which build molecules.[33] The exact nature of these catabolic reactions differ from organism to organism, and organisms can be classified based on their sources of energy, hydrogen, and carbon (their primary nutritional groups), as shown in the table below. Organic molecules are used as a source of hydrogen atoms or electrons by organotrophs, while lithotrophs use inorganic substrates. Whereas phototrophs convert sunlight to chemical energy,[34] chemotrophs depend on redox reactions that involve the transfer of electrons from reduced donor molecules such as organic molecules, hydrogen, hydrogen sulfide or ferrous ions to oxygen, nitrate or sulfate. In animals, these reactions involve complex organic molecules that are broken down to simpler molecules, such as carbon dioxide and water. Photosynthetic organisms, such as plants and cyanobacteria, use similar electron-transfer reactions to store energy absorbed from sunlight.[35]

| Energy source | sunlight | photo- | -troph | ||

| molecules | chemo- | ||||

| Hydrogen or electron donor | organic compound | organo- | |||

| inorganic compound | litho- | ||||

| Carbon source | organic compound | hetero- | |||

| inorganic compound | auto- | ||||

The most common set of catabolic reactions in animals can be separated into three main stages. In the first stage, large organic molecules, such as proteins, polysaccharides or lipids, are digested into their smaller components outside cells. Next, these smaller molecules are taken up by cells and converted to smaller molecules, usually acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which releases some energy. Finally, the acetyl group on acetyl-CoA is oxidized to water and carbon dioxide during the citric acid cycle and electron transport chain, releasing more energy while reducing the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) into NADH.[33]

Digestion

[edit]Macromolecules cannot be directly processed by cells. Macromolecules must be broken into smaller units before they can be used in cell metabolism. Different classes of enzymes are used to digest these polymers. These digestive enzymes include proteases that digest proteins into amino acids, as well as glycoside hydrolases that digest polysaccharides into simple sugars known as monosaccharides.[37]

Microbes simply secrete digestive enzymes into their surroundings,[38][39] while animals only secrete these enzymes from specialized cells in their guts, including the stomach, pancreas, and in salivary glands.[40] The amino acids or sugars released by these extracellular enzymes are then pumped into cells by active transport proteins.[41][42]

Energy from organic compounds

[edit]Carbohydrate catabolism is the breakdown of carbohydrates into smaller units. Carbohydrates are usually taken into cells after they have been digested into monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose.[45] Once inside, the major route of breakdown is glycolysis, in which glucose is converted into pyruvate. This process generates the energy-conveying molecule NADH from NAD+, and generates ATP from ADP for use in powering many processes within the cell.[46] Pyruvate is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways, but the majority is converted to acetyl-CoA and fed into the citric acid cycle, which enables more ATP production by means of oxidative phosphorylation. This oxidation consumes molecular oxygen and releases water and the waste product carbon dioxide. When oxygen is lacking, or when pyruvate is temporarily produced faster than it can be consumed by the citric acid cycle (as in intense muscular exertion), pyruvate is converted to lactate by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase, a process that also oxidizes NADH back to NAD+ for re-use in further glycolysis, allowing energy production to continue.[47] The lactate is later converted back to pyruvate for ATP production where energy is needed, or back to glucose in the Cori cycle. An alternative route for glucose breakdown is the pentose phosphate pathway, which produces less energy but supports anabolism (biomolecule synthesis). This pathway reduces the coenzyme NADP+ to NADPH and produces pentose compounds such as ribose 5-phosphate for synthesis of many biomolecules such as nucleotides and aromatic amino acids.[48]

Fats are catabolized by hydrolysis to free fatty acids and glycerol. The glycerol enters glycolysis and the fatty acids are broken down by beta oxidation to release acetyl-CoA, which then is fed into the citric acid cycle. Fatty acids release more energy upon oxidation than carbohydrates. Steroids are also broken down by some bacteria in a process similar to beta oxidation, and this breakdown process involves the release of significant amounts of acetyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA, and pyruvate, which can all be used by the cell for energy. M. tuberculosis can also grow on the lipid cholesterol as a sole source of carbon, and genes involved in the cholesterol-use pathway(s) have been validated as important during various stages of the infection lifecycle of M. tuberculosis.[49]

Amino acids are either used to synthesize proteins and other biomolecules, or oxidized to urea and carbon dioxide to produce energy.[50] The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase. The amino group is fed into the urea cycle, leaving a deaminated carbon skeleton in the form of a keto acid. Several of these keto acids are intermediates in the citric acid cycle, for example α-ketoglutarate formed by deamination of glutamate.[51] The glucogenic amino acids can also be converted into glucose, through gluconeogenesis.[52]

Energy transformations

[edit]Oxidative phosphorylation

[edit]In oxidative phosphorylation, the electrons removed from organic molecules in areas such as the citric acid cycle are transferred to oxygen and the energy released is used to make ATP. This is done in eukaryotes by a series of proteins in the membranes of mitochondria called the electron transport chain. In prokaryotes, these proteins are found in the cell's inner membrane.[53] These proteins use the energy from reduced molecules like NADH to pump protons across a membrane.[54]

Pumping protons out of the mitochondria creates a proton concentration difference across the membrane and generates an electrochemical gradient.[55] This force drives protons back into the mitochondrion through the base of an enzyme called ATP synthase. The flow of protons makes the stalk subunit rotate, causing the active site of the synthase domain to change shape and phosphorylate adenosine diphosphate—turning it into ATP.[21]

Energy from inorganic compounds

[edit]Chemolithotrophy is a type of metabolism found in prokaryotes where energy is obtained from the oxidation of inorganic compounds. These organisms can use hydrogen,[56] reduced sulfur compounds (such as sulfide, hydrogen sulfide and thiosulfate),[1] ferrous iron (Fe(II))[57] or ammonia[58] as sources of reducing power and they gain energy from the oxidation of these compounds.[59] These microbial processes are important in global biogeochemical cycles such as acetogenesis, nitrification and denitrification and are critical for soil fertility.[60][61]

Energy from light

[edit]The energy in sunlight is captured by plants, cyanobacteria, purple bacteria, green sulfur bacteria and some protists. This process is often coupled to the conversion of carbon dioxide into organic compounds, as part of photosynthesis, which is discussed below. The energy capture and carbon fixation systems can, however, operate separately in prokaryotes, as purple bacteria and green sulfur bacteria can use sunlight as a source of energy, while switching between carbon fixation and the fermentation of organic compounds.[62][63]

In many organisms, the capture of solar energy is similar in principle to oxidative phosphorylation, as it involves the storage of energy as a proton concentration gradient. This proton motive force then drives ATP synthesis.[64] The electrons needed to drive this electron transport chain come from light-gathering proteins called photosynthetic reaction centres. Reaction centers are classified into two types depending on the nature of photosynthetic pigment present, with most photosynthetic bacteria only having one type, while plants and cyanobacteria have two.[65]

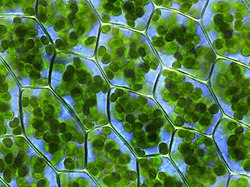

In plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, photosystem II uses light energy to remove electrons from water, releasing oxygen as a waste product. The electrons then flow to the cytochrome b6f complex, which uses their energy to pump protons across the thylakoid membrane in the chloroplast.[35] These protons move back through the membrane as they drive the ATP synthase, as before. The electrons then flow through photosystem I and can then be used to reduce the coenzyme NADP+.[66] This coenzyme can enter the Calvin cycle or be recycled for further ATP generation.[67]

Anabolism

[edit]Anabolism is the set of constructive metabolic processes where the energy released by catabolism is used to synthesize complex molecules. In general, the complex molecules that make up cellular structures are constructed step-by-step from smaller and simpler precursors. Anabolism involves three basic stages. First, the production of precursors such as amino acids, monosaccharides, isoprenoids and nucleotides, secondly, their activation into reactive forms using energy from ATP, and thirdly, the assembly of these precursors into complex molecules such as proteins, polysaccharides, lipids and nucleic acids.[68]

Anabolism in organisms can be different according to the source of constructed molecules in their cells. Autotrophs such as plants can construct the complex organic molecules in their cells such as polysaccharides and proteins from simple molecules like carbon dioxide and water. Heterotrophs, on the other hand, require a source of more complex substances, such as monosaccharides and amino acids, to produce these complex molecules. Organisms can be further classified by ultimate source of their energy: photoautotrophs and photoheterotrophs obtain energy from light, whereas chemoautotrophs and chemoheterotrophs obtain energy from oxidation reactions.[68]

Carbon fixation

[edit]

Photosynthesis is the synthesis of carbohydrates from sunlight and carbon dioxide (CO2). In plants, cyanobacteria and algae, oxygenic photosynthesis splits water, with oxygen produced as a waste product. This process uses the ATP and NADPH produced by the photosynthetic reaction centres, as described above, to convert CO2 into glycerate 3-phosphate, which can then be converted into glucose. This carbon-fixation reaction is carried out by the enzyme RuBisCO as part of the Calvin–Benson cycle.[69] Three types of photosynthesis occur in plants, C3 carbon fixation, C4 carbon fixation and CAM photosynthesis. These differ by the route that carbon dioxide takes to the Calvin cycle, with C3 plants fixing CO2 directly, while C4 and CAM photosynthesis incorporate the CO2 into other compounds first, as adaptations to deal with intense sunlight and dry conditions.[70]

In photosynthetic prokaryotes the mechanisms of carbon fixation are more diverse. Here, carbon dioxide can be fixed by the Calvin–Benson cycle, a reversed citric acid cycle,[71] or the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA.[72][73] Prokaryotic chemoautotrophs also fix CO2 through the Calvin–Benson cycle, but use energy from inorganic compounds to drive the reaction.[74]

Carbohydrates and glycans

[edit]In carbohydrate anabolism, simple organic acids can be converted into monosaccharides such as glucose and then used to assemble polysaccharides such as starch. The generation of glucose from compounds like pyruvate, lactate, glycerol, glycerate 3-phosphate and amino acids is called gluconeogenesis. Gluconeogenesis converts pyruvate to glucose-6-phosphate through a series of intermediates, many of which are shared with glycolysis.[46] However, this pathway is not simply glycolysis run in reverse, as several steps are catalyzed by non-glycolytic enzymes. This is important as it allows the formation and breakdown of glucose to be regulated separately, and prevents both pathways from running simultaneously in a futile cycle.[75][76]

Although fat is a common way of storing energy, in vertebrates such as humans the fatty acids in these stores cannot be converted to glucose through gluconeogenesis as these organisms cannot convert acetyl-CoA into pyruvate; plants do, but animals do not, have the necessary enzymatic machinery.[77] As a result, after long-term starvation, vertebrates need to produce ketone bodies from fatty acids to replace glucose in tissues such as the brain that cannot metabolize fatty acids.[78] In other organisms such as plants and bacteria, this metabolic problem is solved using the glyoxylate cycle, which bypasses the decarboxylation step in the citric acid cycle and allows the transformation of acetyl-CoA to oxaloacetate, where it can be used for the production of glucose.[77][79] Other than fat, glucose is stored in most tissues, as an energy resource available within the tissue through glycogenesis which was usually being used to maintained glucose level in blood.[80]

Polysaccharides and glycans are made by the sequential addition of monosaccharides by glycosyltransferase from a reactive sugar-phosphate donor such as uridine diphosphate glucose (UDP-Glc) to an acceptor hydroxyl group on the growing polysaccharide. As any of the hydroxyl groups on the ring of the substrate can be acceptors, the polysaccharides produced can have straight or branched structures.[81] The polysaccharides produced can have structural or metabolic functions themselves, or be transferred to lipids and proteins by the enzymes oligosaccharyltransferases.[82][83]

Fatty acids, isoprenoids and sterol

[edit]

Fatty acids are made by fatty acid synthases that polymerize and then reduce acetyl-CoA units. The acyl chains in the fatty acids are extended by a cycle of reactions that add the acyl group, reduce it to an alcohol, dehydrate it to an alkene group and then reduce it again to an alkane group. The enzymes of fatty acid biosynthesis are divided into two groups: in animals and fungi, all these fatty acid synthase reactions are carried out by a single multifunctional type I protein,[84] while in plant plastids and bacteria separate type II enzymes perform each step in the pathway.[85][86]

Terpenes and isoprenoids are a large class of lipids that include the carotenoids and form the largest class of plant natural products.[87] These compounds are made by the assembly and modification of isoprene units donated from the reactive precursors isopentenyl pyrophosphate and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate.[88] These precursors can be made in different ways. In animals and archaea, the mevalonate pathway produces these compounds from acetyl-CoA,[89] while in plants and bacteria the non-mevalonate pathway uses pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate as substrates.[88][90] One important reaction that uses these activated isoprene donors is sterol biosynthesis. Here, the isoprene units are joined to make squalene and then folded up and formed into a set of rings to make lanosterol.[91] Lanosterol can then be converted into other sterols such as cholesterol and ergosterol.[91][92]

Proteins

[edit]Organisms vary in their ability to synthesize the 20 common amino acids. Most bacteria and plants can synthesize all twenty, but mammals can only synthesize eleven nonessential amino acids, so nine essential amino acids must be obtained from food.[11] Some simple parasites, such as the bacteria Mycoplasma pneumoniae, lack all amino acid synthesis and take their amino acids directly from their hosts.[93] All amino acids are synthesized from intermediates in glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, or the pentose phosphate pathway. Nitrogen is provided by glutamate and glutamine. Nonessential amino acid synthesis depends on the formation of the appropriate alpha-keto acid, which is then transaminated to form an amino acid.[94]

Amino acids are made into proteins by being joined in a chain of peptide bonds. Each different protein has a unique sequence of amino acid residues: this is its primary structure. Just as the letters of the alphabet can be combined to form an almost endless variety of words, amino acids can be linked in varying sequences to form a huge variety of proteins. Proteins are made from amino acids that have been activated by attachment to a transfer RNA molecule through an ester bond. This aminoacyl-tRNA precursor is produced in an ATP-dependent reaction carried out by an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase.[95] This aminoacyl-tRNA is then a substrate for the ribosome, which joins the amino acid onto the elongating protein chain, using the sequence information in a messenger RNA.[96]

Nucleotide synthesis and salvage

[edit]Nucleotides are made from amino acids, carbon dioxide and formic acid in pathways that require large amounts of metabolic energy.[97] Consequently, most organisms have efficient systems to salvage preformed nucleotides.[97][98] Purines are synthesized as nucleosides (bases attached to ribose).[99] Both adenine and guanine are made from the precursor nucleoside inosine monophosphate, which is synthesized using atoms from the amino acids glycine, glutamine, and aspartic acid, as well as formate transferred from the coenzyme tetrahydrofolate. Pyrimidines, on the other hand, are synthesized from the base orotate, which is formed from glutamine and aspartate.[100]

Xenobiotics and redox metabolism

[edit]All organisms are constantly exposed to compounds that they cannot use as foods and that would be harmful if they accumulated in cells, as they have no metabolic function. These potentially damaging compounds are called xenobiotics.[101] Xenobiotics such as synthetic drugs, natural poisons and antibiotics are detoxified by a set of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes. In humans, these include cytochrome P450 oxidases,[102] UDP-glucuronosyltransferases,[103] and glutathione S-transferases.[104] This system of enzymes acts in three stages to firstly oxidize the xenobiotic (phase I) and then conjugate water-soluble groups onto the molecule (phase II). The modified water-soluble xenobiotic can then be pumped out of cells and in multicellular organisms may be further metabolized before being excreted (phase III). In ecology, these reactions are particularly important in microbial biodegradation of pollutants and the bioremediation of contaminated land and oil spills.[105] Many of these microbial reactions are shared with multicellular organisms, but due to the incredible diversity of types of microbes these organisms are able to deal with a far wider range of xenobiotics than multicellular organisms, and can degrade even persistent organic pollutants such as organochlorines compounds.[106]

A related problem for aerobic organisms is oxidative stress.[107] Here, processes including oxidative phosphorylation and the formation of disulfide bonds during protein folding produce reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide.[108] These damaging oxidants are removed by antioxidant metabolites such as glutathione and enzymes such as catalases and peroxidases.[109][110]

Thermodynamics of living organisms

[edit]Living organisms must obey the laws of thermodynamics, which describe the transfer of heat and work. The second law of thermodynamics states that in any isolated system, the amount of entropy (disorder) cannot decrease. Although living organisms' amazing complexity appears to contradict this law, life is possible as all organisms are open systems that exchange matter and energy with their surroundings. Living systems are not in equilibrium, but instead are dissipative systems that maintain their state of high complexity by causing a larger increase in the entropy of their environments.[111] The metabolism of a cell achieves this by coupling the spontaneous processes of catabolism to the non-spontaneous processes of anabolism. In thermodynamic terms, metabolism maintains order by creating disorder.[112]

Regulation and control

[edit]As the environments of most organisms are constantly changing, the reactions of metabolism must be finely regulated to maintain a constant set of conditions within cells, a condition called homeostasis.[113][114] Metabolic regulation also allows organisms to respond to signals and interact actively with their environments.[115] Two closely linked concepts are important for understanding how metabolic pathways are controlled. Firstly, the regulation of an enzyme in a pathway is how its activity is increased and decreased in response to signals. Secondly, the control exerted by this enzyme is the effect that these changes in its activity have on the overall rate of the pathway (the flux through the pathway).[116] For example, an enzyme may show large changes in activity (i.e. it is highly regulated) but if these changes have little effect on the flux of a metabolic pathway, then this enzyme is not involved in the control of the pathway.[117]

There are multiple levels of metabolic regulation. In intrinsic regulation, the metabolic pathway self-regulates to respond to changes in the levels of substrates or products; for example, a decrease in the amount of product can increase the flux through the pathway to compensate.[116] This type of regulation often involves allosteric regulation of the activities of multiple enzymes in the pathway.[119] Extrinsic control involves a cell in a multicellular organism changing its metabolism in response to signals from other cells. These signals are usually in the form of water-soluble messengers such as hormones and growth factors and are detected by specific receptors on the cell surface.[120] These signals are then transmitted inside the cell by second messenger systems that often involved the phosphorylation of proteins.[121]

A very well understood example of extrinsic control is the regulation of glucose metabolism by the hormone insulin.[122] Insulin is produced in response to rises in blood glucose levels. Binding of the hormone to insulin receptors on cells then activates a cascade of protein kinases that cause the cells to take up glucose and convert it into storage molecules such as fatty acids and glycogen.[123] The metabolism of glycogen is controlled by activity of phosphorylase, the enzyme that breaks down glycogen, and glycogen synthase, the enzyme that makes it. These enzymes are regulated in a reciprocal fashion, with phosphorylation inhibiting glycogen synthase, but activating phosphorylase. Insulin causes glycogen synthesis by activating protein phosphatases and producing a decrease in the phosphorylation of these enzymes.[124]

Evolution

[edit]

The central pathways of metabolism described above, such as glycolysis and the citric acid cycle, are present in all three domains of living things and were present in the last universal common ancestor.[4][125] This universal ancestral cell was prokaryotic and probably a methanogen that had extensive amino acid, nucleotide, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism.[126][127] The retention of these ancient pathways during later evolution may be the result of these reactions having been an optimal solution to their particular metabolic problems, with pathways such as glycolysis and the citric acid cycle producing their end products highly efficiently and in a minimal number of steps.[5][6] The first pathways of enzyme-based metabolism may have been parts of purine nucleotide metabolism, while previous metabolic pathways were a part of the ancient RNA world.[128]

Many models have been proposed to describe the mechanisms by which novel metabolic pathways evolve. These include the sequential addition of novel enzymes to a short ancestral pathway, the duplication and then divergence of entire pathways as well as the recruitment of pre-existing enzymes and their assembly into a novel reaction pathway.[129] The relative importance of these mechanisms is unclear, but genomic studies have shown that enzymes in a pathway are likely to have a shared ancestry, suggesting that many pathways have evolved in a step-by-step fashion with novel functions created from pre-existing steps in the pathway.[130] An alternative model comes from studies that trace the evolution of proteins' structures in metabolic networks, this has suggested that enzymes are pervasively recruited, borrowing enzymes to perform similar functions in different metabolic pathways (evident in the MANET database)[131] These recruitment processes result in an evolutionary enzymatic mosaic.[132] A third possibility is that some parts of metabolism might exist as "modules" that can be reused in different pathways and perform similar functions on different molecules.[133]

As well as the evolution of new metabolic pathways, evolution can also cause the loss of metabolic functions. For example, in some parasites metabolic processes that are not essential for survival are lost and preformed amino acids, nucleotides and carbohydrates may instead be scavenged from the host.[134] Similar reduced metabolic capabilities are seen in endosymbiotic organisms.[135]

Investigation and manipulation

[edit]

Classically, metabolism is studied by a reductionist approach that focuses on a single metabolic pathway. Particularly valuable is the use of radioactive tracers at the whole-organism, tissue and cellular levels, which define the paths from precursors to final products by identifying radioactively labelled intermediates and products.[136] The enzymes that catalyze these chemical reactions can then be purified and their kinetics and responses to inhibitors investigated. A parallel approach is to identify the small molecules in a cell or tissue; the complete set of these molecules is called the metabolome. Overall, these studies give a good view of the structure and function of simple metabolic pathways, but are inadequate when applied to more complex systems such as the metabolism of a complete cell.[137]

An idea of the complexity of the metabolic networks in cells that contain thousands of different enzymes is given by the figure showing the interactions between just 43 proteins and 40 metabolites to the right: the sequences of genomes provide lists containing anything up to 26.500 genes.[138] However, it is now possible to use this genomic data to reconstruct complete networks of biochemical reactions and produce more holistic mathematical models that may explain and predict their behavior.[139] These models are especially powerful when used to integrate the pathway and metabolite data obtained through classical methods with data on gene expression from proteomic and DNA microarray studies.[140] Using these techniques, a model of human metabolism has now been produced, which will guide future drug discovery and biochemical research.[141] These models are now used in network analysis, to classify human diseases into groups that share common proteins or metabolites.[142][143]

Bacterial metabolic networks are a striking example of bow-tie[144][145][146] organization, an architecture able to input a wide range of nutrients and produce a large variety of products and complex macromolecules using a relatively few intermediate common currencies.[147]

A major technological application of this information is metabolic engineering. Here, organisms such as yeast, plants or bacteria are genetically modified to make them more useful in red biotechnology and aid the production of drugs such as antibiotics or industrial chemicals such as 1,3-propanediol and shikimic acid.[148][149][150] These genetic modifications usually aim to reduce the amount of energy used to produce the product, increase yields and reduce the production of wastes.[151]

History

[edit]The term metabolism is derived from the Ancient Greek word μεταβολή—"metabole" for "a change" which is derived from μεταβάλλειν—"metaballein", meaning "to change"[152]

Greek philosophy

[edit]Aristotle's The Parts of Animals sets out enough details of his views on metabolism for an open flow model to be made. He believed that at each stage of the process, materials from food were transformed, with heat being released as the classical element of fire, and residual materials being excreted as urine, bile, or faeces.[153]

Ibn al-Nafis described metabolism in his 1260 AD work titled Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Siera al-Nabawiyyah (The Treatise of Kamil on the Prophet's Biography) which included the following phrase "Both the body and its parts are in a continuous state of dissolution and nourishment, so they are inevitably undergoing permanent change."[154]

Application of the scientific method

[edit]The history of the scientific study of metabolism spans several centuries and has moved from examining whole animals in early studies, to examining individual metabolic reactions in modern biochemistry. The first controlled experiments in human metabolism were published by Santorio Santorio in 1614 in his book Ars de statica medicina. He described how he weighed himself before and after eating, sleep, working, sex, fasting, drinking, and excreting. He found that most of the food he took in was lost through what he called "insensible perspiration".[155]

In these early studies, the mechanisms of these metabolic processes had not been identified and a vital force was thought to animate living tissue.[156] In the 19th century, when studying the fermentation of sugar to alcohol by yeast, Louis Pasteur concluded that fermentation was catalyzed by substances within the yeast cells he called "ferments". He wrote that "alcoholic fermentation is an act correlated with the life and organization of the yeast cells, not with the death or putrefaction of the cells."[157] This discovery, along with the publication by Friedrich Wöhler in 1828 of a paper on the chemical synthesis of urea, and is notable for being the first organic compound prepared from wholly inorganic precursors.[158] Wöhler's urea synthesis showed that organic compounds could be created from inorganic precursors, disputing the vital force theory that dominated early 19th-century science. Modern analyses consider this achievement as foundational for unifying organic and inorganic chemistry.[159]

It was the discovery of enzymes at the beginning of the 20th century by Eduard Buchner that separated the study of the chemical reactions of metabolism from the biological study of cells, and marked the beginnings of biochemistry.[160] The mass of biochemical knowledge grew rapidly throughout the early 20th century. One of the most prolific of these modern biochemists was Hans Krebs who made huge contributions to the study of metabolism.[161] He discovered the urea cycle and later, working with Hans Kornberg, the citric acid cycle and the glyoxylate cycle.[162][163][79] Modern biochemical research has been greatly aided by the development of new techniques such as chromatography, NMR spectroscopy, electron microscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. These techniques have allowed the discovery and detailed analysis of the many molecules and metabolic pathways in cells.[164]

See also

[edit]- Anthropogenic metabolism – Material and energy turnover of human society

- Antimetabolite – Chemical that inhibits the use of a metabolite

- Calorimetry – Determining heat transfer in a system by measuring its other properties

- Isothermal microcalorimetry – Measuring versus elapsed time the net rate of heat flow

- Inborn errors of metabolism – Class of genetic diseases

- Iron–sulfur world hypothesis – Hypothetical scenario for the origin of life, a "metabolism first" theory of the origin of life

- Metabolic disorder – Any disease hindering the body's ability to process and distribute nutrients

- Microphysiometry

- Primary nutritional groups – Group of organisms

- Proto-metabolism – Chemical reactions which turn into modern metabolism

- Respirometry – Estimation of metabolic rates by measuring heat production

- Stream metabolism

- Sulfur metabolism – Set of chemical reactions involving sulfur in living organisms

- Thermic effect of food – Energy expenditure for processing food

- Urban metabolism – Model of the flows of materials and energy in cities

- Water metabolism – Aspect of homeostasis concerning control of the amount of water in an organism

- Overflow metabolism – Cellular phenomena

- Oncometabolism

- Reactome

- KEGG – Collection of bioinformatics databases

References

[edit]- ^ a b Friedrich, CG (1997). Physiology and Genetics of Sulfur-oxidizing Bacteria. Advances in Microbial Physiology. Vol. 39. pp. 235–89. doi:10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60018-1. ISBN 978-0-12-027739-1. PMID 9328649.

- ^ Cirino, Giuseppe; Szabo, Csaba; Papapetropoulos, Andreas (January 2023). "Physiological roles of hydrogen sulfide in mammalian cells, tissues, and organs". Physiological Reviews. 103 (1): 31–276. doi:10.1152/physrev.00028.2021. ISSN 0031-9333. PMID 35435014.

- ^ Pace NR (January 2001). "The universal nature of biochemistry". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (3): 805–8. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98..805P. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.3.805. PMC 33372. PMID 11158550.

- ^ a b Smith E, Morowitz HJ (September 2004). "Universality in intermediary metabolism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (36): 13168–73. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10113168S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0404922101. PMC 516543. PMID 15340153.

- ^ a b Ebenhöh O, Heinrich R (January 2001). "Evolutionary optimization of metabolic pathways. Theoretical reconstruction of the stoichiometry of ATP and NADH producing systems". Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 63 (1): 21–55. doi:10.1006/bulm.2000.0197. PMID 11146883. S2CID 44260374.

- ^ a b Meléndez-Hevia E, Waddell TG, Cascante M (September 1996). "The puzzle of the Krebs citric acid cycle: assembling the pieces of chemically feasible reactions, and opportunism in the design of metabolic pathways during evolution". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 43 (3): 293–303. Bibcode:1996JMolE..43..293M. doi:10.1007/BF02338838. PMID 8703096. S2CID 19107073.

- ^ Smith RL, Soeters MR, Wüst RC, Houtkooper RH (August 2018). "Metabolic Flexibility as an Adaptation to Energy Resources and Requirements in Health and Disease". Endocrine Reviews. 39 (4): 489–517. doi:10.1210/er.2017-00211. PMC 6093334. PMID 29697773.

- ^ Vander Heiden MG, DeBerardinis RJ (February 2017). "Understanding the Intersections between Metabolism and Cancer Biology". Cell. 168 (4): 657–669. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.039. PMC 5329766. PMID 28187287.

- ^ Cooper GM (2000). "The Molecular Composition of Cells". The Cell: A Molecular Approach (2nd ed.). Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Michie KA, Löwe J (2006). "Dynamic filaments of the bacterial cytoskeleton". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 75: 467–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142452. PMID 16756499. S2CID 4550126.

- ^ a b c d e Nelson DL, Cox MM (2005). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. New York: W. H. Freeman and company. p. 841. ISBN 978-0-7167-4339-2.

- ^ Kelleher JK, Bryan BM, Mallet RT, Holleran AL, Murphy AN, Fiskum G (September 1987). "Analysis of tricarboxylic acid-cycle metabolism of hepatoma cells by comparison of 14CO2 ratios". The Biochemical Journal. 246 (3): 633–9. doi:10.1042/bj2460633. PMC 1148327. PMID 3120698.

- ^ Hothersall JS, Ahmed A (2013). "Metabolic fate of the increased yeast amino Acid uptake subsequent to catabolite derepression". Journal of Amino Acids. 2013 461901. doi:10.1155/2013/461901. PMC 3575661. PMID 23431419.

- ^ Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Brown HA, Glass CK, Merrill AH, Murphy RC, et al. (May 2005). "A comprehensive classification system for lipids". Journal of Lipid Research. 46 (5): 839–61. doi:10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200. PMID 15722563.

- ^ "Lipid nomenclature Lip-1 & Lip-2". qmul.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Gatto Jr GJ, Stryer L (8 April 2015). Biochemistry (8 ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. p. 362. ISBN 978-1-4641-2610-9. OCLC 913469736.

- ^ Raman R, Raguram S, Venkataraman G, Paulson JC, Sasisekharan R (November 2005). "Glycomics: an integrated systems approach to structure-function relationships of glycans". Nature Methods. 2 (11): 817–24. doi:10.1038/nmeth807. PMID 16278650. S2CID 4644919.

- ^ Sierra S, Kupfer B, Kaiser R (December 2005). "Basics of the virology of HIV-1 and its replication". Journal of Clinical Virology. 34 (4): 233–44. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.004. PMID 16198625.

- ^ a b Wimmer MJ, Rose IA (1978). "Mechanisms of enzyme-catalyzed group transfer reactions". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 47: 1031–78. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.005123. PMID 354490.

- ^ Mitchell P (March 1979). "The Ninth Sir Hans Krebs Lecture. Compartmentation and communication in living systems. Ligand conduction: a general catalytic principle in chemical, osmotic and chemiosmotic reaction systems". European Journal of Biochemistry. 95 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb12934.x. PMID 378655.

- ^ a b c Dimroth P, von Ballmoos C, Meier T (March 2006). "Catalytic and mechanical cycles in F-ATP synthases. Fourth in the Cycles Review Series". EMBO Reports. 7 (3): 276–82. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400646. PMC 1456893. PMID 16607397.

- ^ Bonora M, Patergnani S, Rimessi A, De Marchi E, Suski JM, Bononi A, et al. (September 2012). "ATP synthesis and storage". Purinergic Signalling. 8 (3): 343–57. doi:10.1007/s11302-012-9305-8. PMC 3360099. PMID 22528680.

- ^ Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L (2002). "Vitamins Are Often Precursors to Coenzymes". Biochemistry. 5th Edition. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Pollak N, Dölle C, Ziegler M (March 2007). "The power to reduce: pyridine nucleotides--small molecules with a multitude of functions". The Biochemical Journal. 402 (2): 205–18. doi:10.1042/BJ20061638. PMC 1798440. PMID 17295611.

- ^ Fatih Y (2009). Advances in food biochemistry. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4200-0769-5. OCLC 607553259.

- ^ Heymsfield SB, Waki M, Kehayias J, Lichtman S, Dilmanian FA, Kamen Y, et al. (August 1991). "Chemical and elemental analysis of humans in vivo using improved body composition models". The American Journal of Physiology. 261 (2 Pt 1): E190-8. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.2.E190. PMID 1872381.

- ^ "Electrolyte Balance". Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell J (2000). "The Action Potential and Conduction of Electric Impulses". Molecular Cell Biology (4th ed.). Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020 – via NCBI.

- ^ Dulhunty AF (September 2006). "Excitation-contraction coupling from the 1950s into the new millennium". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 33 (9): 763–72. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04441.x. PMID 16922804. S2CID 37462321.

- ^ Torres-Romero JC, Alvarez-Sánchez ME, Fernández-Martín K, Alvarez-Sánchez LC, Arana-Argáez V, Ramírez-Camacho M, Lara-Riegos J (2018). "Zinc Efflux in Trichomonas vaginalis: In Silico Identification and Expression Analysis of CDF-Like Genes". In Olivares-Quiroz L, Resendis-Antonio O (eds.). Quantitative Models for Microscopic to Macroscopic Biological Macromolecules and Tissues. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 149–168. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73975-5_8. ISBN 978-3-319-73975-5.

- ^ Cousins RJ, Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA (August 2006). "Mammalian zinc transport, trafficking, and signals". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (34): 24085–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.R600011200. PMID 16793761.

- ^ Dunn LL, Suryo Rahmanto Y, Richardson DR (February 2007). "Iron uptake and metabolism in the new millennium". Trends in Cell Biology. 17 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.003. PMID 17194590.

- ^ a b Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). "How Cells Obtain Energy from Food". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Archived from the original on 5 July 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2020 – via NCBI.

- ^ Raven J (3 September 2009). "Contributions of anoxygenic and oxygenic phototrophy and chemolithotrophy to carbon and oxygen fluxes in aquatic environments". Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 56: 177–192. doi:10.3354/ame01315. ISSN 0948-3055. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ a b Nelson N, Ben-Shem A (December 2004). "The complex architecture of oxygenic photosynthesis". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 5 (12): 971–82. doi:10.1038/nrm1525. PMID 15573135. S2CID 5686066.

- ^ Madigan MT, Martinko JM (2006). Brock Mikrobiologie (11., überarb. Aufl ed.). München: Pearson Studium. pp. 604, 621. ISBN 3-8273-7187-2. OCLC 162303067.

- ^ Demirel Y (2016). Energy: production, conversion, storage, conservation, and coupling (Second ed.). Lincoln: Springer. p. 431. ISBN 978-3-319-29650-0. OCLC 945435943.

- ^ Häse CC, Finkelstein RA (December 1993). "Bacterial extracellular zinc-containing metalloproteases". Microbiological Reviews. 57 (4): 823–37. doi:10.1128/MMBR.57.4.823-837.1993. PMC 372940. PMID 8302217.

- ^ Gupta R, Gupta N, Rathi P (June 2004). "Bacterial lipases: an overview of production, purification and biochemical properties". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 64 (6): 763–81. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1568-8. PMID 14966663. S2CID 206934353.

- ^ Hoyle T (1997). "The digestive system: linking theory and practice". British Journal of Nursing. 6 (22): 1285–91. doi:10.12968/bjon.1997.6.22.1285. PMID 9470654.

- ^ Souba WW, Pacitti AJ (1992). "How amino acids get into cells: mechanisms, models, menus, and mediators". Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 16 (6): 569–78. doi:10.1177/0148607192016006569. PMID 1494216.

- ^ Barrett MP, Walmsley AR, Gould GW (August 1999). "Structure and function of facilitative sugar transporters". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 11 (4): 496–502. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80072-6. PMID 10449337.

- ^ Sinthupoom, Nujarin; Prachayasittikul, Veda; Prachayasittikul, Supaluk; Ruchirawat, Somsak; Prachayasittikul, Virapong (2015). "Nicotinic acid and derivatives as multifunctional pharmacophores for medical applications". European Food Research and Technology. 240 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/s00217-014-2354-1. ISSN 1438-2377. Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- ^ Clark, Audra; Imran, Jonathan; Madni, Tarik; Wolf, Steven E. (1 December 2017). "Nutrition and metabolism in burn patients". Burns & Trauma. 5: 11. doi:10.1186/s41038-017-0076-x. ISSN 2321-3876. PMC 5393025. PMID 28428966.

- ^ Bell GI, Burant CF, Takeda J, Gould GW (September 1993). "Structure and function of mammalian facilitative sugar transporters". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (26): 19161–4. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)36489-0. PMID 8366068.

- ^ a b Bouché C, Serdy S, Kahn CR, Goldfine AB (October 2004). "The cellular fate of glucose and its relevance in type 2 diabetes". Endocrine Reviews. 25 (5): 807–30. doi:10.1210/er.2003-0026. PMID 15466941.

- ^ Alfarouk KO, Verduzco D, Rauch C, Muddathir AK, Adil HH, Elhassan GO, et al. (18 December 2014). "Glycolysis, tumor metabolism, cancer growth and dissemination. A new pH-based etiopathogenic perspective and therapeutic approach to an old cancer question". Oncoscience. 1 (12): 777–802. doi:10.18632/oncoscience.109. PMC 4303887. PMID 25621294.

- ^ Kruger, Nicholas J; von Schaewen, Antje (2003). "The oxidative pentose phosphate pathway: structure and organisation". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 6 (3): 236–246. Bibcode:2003COPB....6..236K. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00039-6. PMID 12753973.

- ^ Wipperman MF, Sampson NS, Thomas ST (2014). "Pathogen roid rage: cholesterol utilization by Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 49 (4): 269–93. doi:10.3109/10409238.2014.895700. PMC 4255906. PMID 24611808.

- ^ Sakami W, Harrington H (1963). "Amino Acid Metabolism". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 32: 355–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.32.070163.002035. PMID 14144484.

- ^ Brosnan JT (April 2000). "Glutamate, at the interface between amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4S Suppl): 988S – 90S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.988S. PMID 10736367.

- ^ Young VR, Ajami AM (September 2001). "Glutamine: the emperor or his clothes?". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (9 Suppl): 2449S – 59S, discussion 2486S–7S. doi:10.1093/jn/131.9.2449S. PMID 11533293.

- ^ Hosler JP, Ferguson-Miller S, Mills DA (2006). "Energy transduction: proton transfer through the respiratory complexes". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 75: 165–87. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.062003.101730. PMC 2659341. PMID 16756489.

- ^ Schultz BE, Chan SI (2001). "Structures and proton-pumping strategies of mitochondrial respiratory enzymes" (PDF). Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 30: 23–65. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.23. PMID 11340051. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Capaldi RA, Aggeler R (March 2002). "Mechanism of the F(1)F(0)-type ATP synthase, a biological rotary motor". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 27 (3): 154–60. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(01)02051-5. PMID 11893513.

- ^ Friedrich B, Schwartz E (1993). "Molecular biology of hydrogen utilization in aerobic chemolithotrophs". Annual Review of Microbiology. 47: 351–83. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002031. PMID 8257102.

- ^ Weber KA, Achenbach LA, Coates JD (October 2006). "Microorganisms pumping iron: anaerobic microbial iron oxidation and reduction". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 4 (10): 752–64. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1490. PMID 16980937. S2CID 8528196. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Jetten MS, Strous M, van de Pas-Schoonen KT, Schalk J, van Dongen UG, van de Graaf AA, et al. (December 1998). "The anaerobic oxidation of ammonium". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 22 (5): 421–37. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00379.x. PMID 9990725.

- ^ Simon J (August 2002). "Enzymology and bioenergetics of respiratory nitrite ammonification". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 26 (3): 285–309. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00616.x. PMID 12165429.

- ^ Conrad R (December 1996). "Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O, and NO)". Microbiological Reviews. 60 (4): 609–40. doi:10.1128/MMBR.60.4.609-640.1996. PMC 239458. PMID 8987358.

- ^ Barea JM, Pozo MJ, Azcón R, Azcón-Aguilar C (July 2005). "Microbial co-operation in the rhizosphere". Journal of Experimental Botany. 56 (417): 1761–78. doi:10.1093/jxb/eri197. PMID 15911555.

- ^ van der Meer MT, Schouten S, Bateson MM, Nübel U, Wieland A, Kühl M, et al. (July 2005). "Diel variations in carbon metabolism by green nonsulfur-like bacteria in alkaline siliceous hot spring microbial mats from Yellowstone National Park". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 71 (7): 3978–86. Bibcode:2005ApEnM..71.3978V. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.7.3978-3986.2005. PMC 1168979. PMID 16000812.

- ^ Tichi MA, Tabita FR (November 2001). "Interactive control of Rhodobacter capsulatus redox-balancing systems during phototrophic metabolism". Journal of Bacteriology. 183 (21): 6344–54. doi:10.1128/JB.183.21.6344-6354.2001. PMC 100130. PMID 11591679.

- ^ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). "Energy Conversion: Mitochondria and Chloroplasts". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Allen JP, Williams JC (October 1998). "Photosynthetic reaction centers". FEBS Letters. 438 (1–2): 5–9. Bibcode:1998FEBSL.438....5A. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01245-9. PMID 9821949. S2CID 21596537.

- ^ Munekage Y, Hashimoto M, Miyake C, Tomizawa K, Endo T, Tasaka M, Shikanai T (June 2004). "Cyclic electron flow around photosystem I is essential for photosynthesis". Nature. 429 (6991): 579–82. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..579M. doi:10.1038/nature02598. PMID 15175756. S2CID 4421776.

- ^ Michelet, Laure; Zaffagnini, Mirko; Morisse, Samuel; Sparla, Francesca; Pérez-Pérez, María Esther; Francia, Francesco; Danon, Antoine; Marchand, Christophe; Fermani, Simona; Trost, Paolo; Lemaire, Stéphane D. (25 November 2013). "Redox regulation of the Calvin–Benson cycle: something old, something new". Frontiers in Plant Science. 4: 470. Bibcode:2013FrPS....4..470M. doi:10.3389/fpls.2013.00470. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 3838966. PMID 24324475.

- ^ a b Mandal A (26 November 2009). "What is Anabolism?". News-Medical.net. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Miziorko HM, Lorimer GH (1983). "Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 52: 507–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.002451. PMID 6351728.

- ^ Dodd AN, Borland AM, Haslam RP, Griffiths H, Maxwell K (April 2002). "Crassulacean acid metabolism: plastic, fantastic". Journal of Experimental Botany. 53 (369): 569–80. doi:10.1093/jexbot/53.369.569. PMID 11886877.

- ^ Hügler M, Wirsen CO, Fuchs G, Taylor CD, Sievert SM (May 2005). "Evidence for autotrophic CO2 fixation via the reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle by members of the epsilon subdivision of proteobacteria". Journal of Bacteriology. 187 (9): 3020–7. doi:10.1128/JB.187.9.3020-3027.2005. PMC 1082812. PMID 15838028.

- ^ Strauss G, Fuchs G (August 1993). "Enzymes of a novel autotrophic CO2 fixation pathway in the phototrophic bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus, the 3-hydroxypropionate cycle". European Journal of Biochemistry. 215 (3): 633–43. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18074.x. PMID 8354269.

- ^ Wood HG (February 1991). "Life with CO or CO2 and H2 as a source of carbon and energy". FASEB Journal. 5 (2): 156–63. doi:10.1096/fasebj.5.2.1900793. PMID 1900793. S2CID 45967404.

- ^ Shively JM, van Keulen G, Meijer WG (1998). "Something from almost nothing: carbon dioxide fixation in chemoautotrophs". Annual Review of Microbiology. 52: 191–230. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.191. PMID 9891798.

- ^ Boiteux A, Hess B (June 1981). "Design of glycolysis". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 293 (1063): 5–22. Bibcode:1981RSPTB.293....5B. doi:10.1098/rstb.1981.0056. PMID 6115423.

- ^ Pilkis SJ, el-Maghrabi MR, Claus TH (June 1990). "Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate in control of hepatic gluconeogenesis. From metabolites to molecular genetics". Diabetes Care. 13 (6): 582–99. doi:10.2337/diacare.13.6.582. PMID 2162755. S2CID 44741368.

- ^ a b Ensign SA (July 2006). "Revisiting the glyoxylate cycle: alternate pathways for microbial acetate assimilation". Molecular Microbiology. 61 (2): 274–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05247.x. PMID 16856935. S2CID 39986630.

- ^ Finn PF, Dice JF (2006). "Proteolytic and lipolytic responses to starvation". Nutrition. 22 (7–8): 830–44. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2006.04.008. PMID 16815497.

- ^ a b Kornberg HL, Krebs HA (May 1957). "Synthesis of cell constituents from C2-units by a modified tricarboxylic acid cycle". Nature. 179 (4568): 988–91. Bibcode:1957Natur.179..988K. doi:10.1038/179988a0. PMID 13430766. S2CID 40858130.

- ^ Evans RD, Heather LC (June 2016). "Metabolic pathways and abnormalities". Surgery (Oxford). 34 (6): 266–272. doi:10.1016/j.mpsur.2016.03.010. ISSN 0263-9319. S2CID 87884121. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Freeze HH, Hart GW, Schnaar RL (2015). "Glycosylation Precursors". In Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Stanley P (eds.). Essentials of Glycobiology (3rd ed.). Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. doi:10.1101/glycobiology.3e.005 (inactive 1 July 2025). PMID 28876856. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Opdenakker G, Rudd PM, Ponting CP, Dwek RA (November 1993). "Concepts and principles of glycobiology". FASEB Journal. 7 (14): 1330–7. doi:10.1096/fasebj.7.14.8224606. PMID 8224606. S2CID 10388991.

- ^ McConville MJ, Menon AK (2000). "Recent developments in the cell biology and biochemistry of glycosylphosphatidylinositol lipids (review)". Molecular Membrane Biology. 17 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/096876800294443. PMID 10824734.

- ^ Chirala SS, Wakil SJ (November 2004). "Structure and function of animal fatty acid synthase". Lipids. 39 (11): 1045–53. doi:10.1007/s11745-004-1329-9. PMID 15726818. S2CID 4043407.

- ^ White SW, Zheng J, Zhang YM (2005). "The structural biology of type II fatty acid biosynthesis". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 74: 791–831. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133524. PMID 15952903.

- ^ Ohlrogge JB, Jaworski JG (June 1997). "Regulation of Fatty Acid Synthesis". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 48: 109–136. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.109. PMID 15012259. S2CID 46348092.

- ^ Dubey VS, Bhalla R, Luthra R (September 2003). "An overview of the non-mevalonate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis in plants" (PDF). Journal of Biosciences. 28 (5): 637–46. doi:10.1007/BF02703339. PMID 14517367. S2CID 27523830. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2007.

- ^ a b Kuzuyama T, Seto H (April 2003). "Diversity of the biosynthesis of the isoprene units". Natural Product Reports. 20 (2): 171–83. doi:10.1039/b109860h. PMID 12735695.

- ^ Grochowski LL, Xu H, White RH (May 2006). "Methanocaldococcus jannaschii uses a modified mevalonate pathway for biosynthesis of isopentenyl diphosphate". Journal of Bacteriology. 188 (9): 3192–8. doi:10.1128/JB.188.9.3192-3198.2006. PMC 1447442. PMID 16621811.

- ^ Lichtenthaler HK (June 1999). "The 1-Deoxy-D-Xylulose-5-Phosphate Pathway of Isoprenoid Biosynthesis in Plants". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 50: 47–65. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.47. PMID 15012203.

- ^ a b Schroepfer GJ (1981). "Sterol biosynthesis". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 50: 585–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.003101. PMID 7023367.

- ^ Lees ND, Skaggs B, Kirsch DR, Bard M (March 1995). "Cloning of the late genes in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae--a review". Lipids. 30 (3): 221–6. doi:10.1007/BF02537824. PMID 7791529. S2CID 4019443.

- ^ Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li BC, Herrmann R (November 1996). "Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae". Nucleic Acids Research. 24 (22): 4420–49. doi:10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. PMC 146264. PMID 8948633.

- ^ Guyton AC, Hall JE (2006). Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 855–6. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- ^ Ibba M, Söll D (May 2001). "The renaissance of aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis". EMBO Reports. 2 (5): 382–7. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve095. PMC 1083889. PMID 11375928. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011.

- ^ Lengyel P, Söll D (June 1969). "Mechanism of protein biosynthesis". Bacteriological Reviews. 33 (2): 264–301. doi:10.1128/MMBR.33.2.264-301.1969. PMC 378322. PMID 4896351.

- ^ a b Rudolph FB (January 1994). "The biochemistry and physiology of nucleotides". The Journal of Nutrition. 124 (1 Suppl): 124S – 127S. doi:10.1093/jn/124.suppl_1.124S. PMID 8283301. Zrenner R, Stitt M, Sonnewald U, Boldt R (2006). "Pyrimidine and purine biosynthesis and degradation in plants". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 57 (1): 805–36. Bibcode:2006AnRPB..57..805Z. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105421. PMID 16669783.

- ^ Stasolla C, Katahira R, Thorpe TA, Ashihara H (November 2003). "Purine and pyrimidine nucleotide metabolism in higher plants". Journal of Plant Physiology. 160 (11): 1271–95. Bibcode:2003JPPhy.160.1271S. doi:10.1078/0176-1617-01169. PMID 14658380.

- ^ Davies O, Mendes P, Smallbone K, Malys N (April 2012). "Characterisation of multiple substrate-specific (d)ITP/(d)XTPase and modelling of deaminated purine nucleotide metabolism" (PDF). BMB Reports. 45 (4): 259–64. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2012.45.4.259. PMID 22531138. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ Smith JL (December 1995). "Enzymes of nucleotide synthesis". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 5 (6): 752–7. doi:10.1016/0959-440X(95)80007-7. PMID 8749362.

- ^ Testa B, Krämer SD (October 2006). "The biochemistry of drug metabolism--an introduction: part 1. Principles and overview". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 3 (10): 1053–101. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200690111. PMID 17193224. S2CID 28872968.

- ^ Danielson PB (December 2002). "The cytochrome P450 superfamily: biochemistry, evolution and drug metabolism in humans". Current Drug Metabolism. 3 (6): 561–97. doi:10.2174/1389200023337054. PMID 12369887.

- ^ King CD, Rios GR, Green MD, Tephly TR (September 2000). "UDP-glucuronosyltransferases". Current Drug Metabolism. 1 (2): 143–61. doi:10.2174/1389200003339171. PMID 11465080.

- ^ Sheehan D, Meade G, Foley VM, Dowd CA (November 2001). "Structure, function and evolution of glutathione transferases: implications for classification of non-mammalian members of an ancient enzyme superfamily". The Biochemical Journal. 360 (Pt 1): 1–16. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3600001. PMC 1222196. PMID 11695986.

- ^ Galvão TC, Mohn WW, de Lorenzo V (October 2005). "Exploring the microbial biodegradation and biotransformation gene pool". Trends in Biotechnology. 23 (10): 497–506. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.08.002. PMID 16125262.

- ^ Janssen DB, Dinkla IJ, Poelarends GJ, Terpstra P (December 2005). "Bacterial degradation of xenobiotic compounds: evolution and distribution of novel enzyme activities" (PDF). Environmental Microbiology. 7 (12): 1868–82. Bibcode:2005EnvMi...7.1868J. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00966.x. PMID 16309386. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Davies KJ (1995). "Oxidative stress: the paradox of aerobic life". Biochemical Society Symposium. 61: 1–31. doi:10.1042/bss0610001. PMID 8660387.

- ^ Tu BP, Weissman JS (February 2004). "Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: mechanisms and consequences". The Journal of Cell Biology. 164 (3): 341–6. doi:10.1083/jcb.200311055. PMC 2172237. PMID 14757749.

- ^ Sies H (March 1997). "Oxidative stress: oxidants and antioxidants". Experimental Physiology. 82 (2): 291–5. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004024. PMID 9129943. S2CID 20240552.

- ^ Vertuani S, Angusti A, Manfredini S (2004). "The antioxidants and pro-antioxidants network: an overview". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 10 (14): 1677–94. doi:10.2174/1381612043384655. PMID 15134565. S2CID 43713549.

- ^ von Stockar U, Liu J (August 1999). "Does microbial life always feed on negative entropy? Thermodynamic analysis of microbial growth". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1412 (3): 191–211. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(99)00065-1. PMID 10482783.

- ^ Demirel Y, Sandler SI (June 2002). "Thermodynamics and bioenergetics". Biophysical Chemistry. 97 (2–3): 87–111. doi:10.1016/S0301-4622(02)00069-8. PMID 12050002. S2CID 3754065. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Albert R (November 2005). "Scale-free networks in cell biology". Journal of Cell Science. 118 (Pt 21): 4947–57. arXiv:q-bio/0510054. Bibcode:2005q.bio....10054A. doi:10.1242/jcs.02714. PMID 16254242. S2CID 3001195.

- ^ Brand MD (January 1997). "Regulation analysis of energy metabolism". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 200 (Pt 2): 193–202. Bibcode:1997JExpB.200..193B. doi:10.1242/jeb.200.2.193. PMID 9050227. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- ^ Soyer OS, Salathé M, Bonhoeffer S (January 2006). "Signal transduction networks: topology, response and biochemical processes". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 238 (2): 416–25. Bibcode:2006JThBi.238..416S. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.05.030. PMID 16045939.

- ^ a b Salter M, Knowles RG, Pogson CI (1994). "Metabolic control". Essays in Biochemistry. 28: 1–12. PMID 7925313.

- ^ Westerhoff HV, Groen AK, Wanders RJ (January 1984). "Modern theories of metabolic control and their applications (review)". Bioscience Reports. 4 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1007/BF01120819. PMID 6365197. S2CID 27791605.

- ^ Chouhan, Raje; Goswami, Shilpi; Bajpai, Anil Kumar (2017). "Recent advancements in oral delivery of insulin: from challenges to solutions". Nanostructures for Oral Medicine. Elsevier. pp. 435–465. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-47720-8.00016-x. ISBN 978-0-323-47720-8. Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- ^ Fell DA, Thomas S (October 1995). "Physiological control of metabolic flux: the requirement for multisite modulation". The Biochemical Journal. 311 (Pt 1): 35–9. doi:10.1042/bj3110035. PMC 1136115. PMID 7575476.

- ^ Hendrickson WA (November 2005). "Transduction of biochemical signals across cell membranes". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 38 (4): 321–30. doi:10.1017/S0033583506004136. PMID 16600054. S2CID 39154236.

- ^ Cohen P (December 2000). "The regulation of protein function by multisite phosphorylation--a 25 year update". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 25 (12): 596–601. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01712-6. PMID 11116185.

- ^ Lienhard GE, Slot JW, James DE, Mueckler MM (January 1992). "How cells absorb glucose". Scientific American. 266 (1): 86–91. Bibcode:1992SciAm.266a..86L. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0192-86. PMID 1734513.

- ^ Roach PJ (March 2002). "Glycogen and its metabolism". Current Molecular Medicine. 2 (2): 101–20. doi:10.2174/1566524024605761. PMID 11949930.

- ^ Newgard CB, Brady MJ, O'Doherty RM, Saltiel AR (December 2000). "Organizing glucose disposal: emerging roles of the glycogen targeting subunits of protein phosphatase-1" (PDF). Diabetes. 49 (12): 1967–77. doi:10.2337/diabetes.49.12.1967. PMID 11117996. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ^ Romano AH, Conway T (1996). "Evolution of carbohydrate metabolic pathways". Research in Microbiology. 147 (6–7): 448–55. doi:10.1016/0923-2508(96)83998-2. PMID 9084754.

- ^ Koch A (1998). "How Did Bacteria Come to Be?". Advances in Microbial Physiology. 40: 353–99. doi:10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60135-6. ISBN 978-0-12-027740-7. PMID 9889982.

- ^ Ouzounis C, Kyrpides N (July 1996). "The emergence of major cellular processes in evolution". FEBS Letters. 390 (2): 119–23. Bibcode:1996FEBSL.390..119O. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00631-X. PMID 8706840. S2CID 39128865.

- ^ Caetano-Anollés G, Kim HS, Mittenthal JE (May 2007). "The origin of modern metabolic networks inferred from phylogenomic analysis of protein architecture". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (22): 9358–63. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.9358C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701214104. PMC 1890499. PMID 17517598.

- ^ Schmidt S, Sunyaev S, Bork P, Dandekar T (June 2003). "Metabolites: a helping hand for pathway evolution?". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 28 (6): 336–41. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00114-2. PMID 12826406.

- ^ Light S, Kraulis P (February 2004). "Network analysis of metabolic enzyme evolution in Escherichia coli". BMC Bioinformatics. 5 15. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-5-15. PMC 394313. PMID 15113413. Alves R, Chaleil RA, Sternberg MJ (July 2002). "Evolution of enzymes in metabolism: a network perspective". Journal of Molecular Biology. 320 (4): 751–70. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00546-6. PMID 12095253.

- ^ Kim HS, Mittenthal JE, Caetano-Anollés G (July 2006). "MANET: tracing evolution of protein architecture in metabolic networks". BMC Bioinformatics. 7 351. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-7-351. PMC 1559654. PMID 16854231.

- ^ Teichmann SA, Rison SC, Thornton JM, Riley M, Gough J, Chothia C (December 2001). "Small-molecule metabolism: an enzyme mosaic". Trends in Biotechnology. 19 (12): 482–6. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(01)01813-3. PMID 11711174.

- ^ Spirin V, Gelfand MS, Mironov AA, Mirny LA (June 2006). "A metabolic network in the evolutionary context: multiscale structure and modularity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (23): 8774–9. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.8774S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510258103. PMC 1482654. PMID 16731630.

- ^ Lawrence JG (December 2005). "Common themes in the genome strategies of pathogens". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 15 (6): 584–8. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.007. PMID 16188434. Wernegreen JJ (December 2005). "For better or worse: genomic consequences of intracellular mutualism and parasitism". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 15 (6): 572–83. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.013. PMID 16230003.

- ^ Pál C, Papp B, Lercher MJ, Csermely P, Oliver SG, Hurst LD (March 2006). "Chance and necessity in the evolution of minimal metabolic networks". Nature. 440 (7084): 667–70. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..667P. doi:10.1038/nature04568. PMID 16572170. S2CID 4424895.

- ^ Rennie MJ (November 1999). "An introduction to the use of tracers in nutrition and metabolism". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 58 (4): 935–44. doi:10.1017/S002966519900124X. PMID 10817161.

- ^ Phair RD (December 1997). "Development of kinetic models in the nonlinear world of molecular cell biology". Metabolism. 46 (12): 1489–95. doi:10.1016/S0026-0495(97)90154-2. PMID 9439549.

- ^ Sterck L, Rombauts S, Vandepoele K, Rouzé P, Van de Peer Y (April 2007). "How many genes are there in plants (... and why are they there)?". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 10 (2): 199–203. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2007.01.004. PMID 17289424.

- ^ Borodina I, Nielsen J (June 2005). "From genomes to in silico cells via metabolic networks". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 16 (3): 350–5. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2005.04.008. PMID 15961036.

- ^ Gianchandani EP, Brautigan DL, Papin JA (May 2006). "Systems analyses characterize integrated functions of biochemical networks". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 31 (5): 284–91. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.007. PMID 16616498.

- ^ Duarte NC, Becker SA, Jamshidi N, Thiele I, Mo ML, Vo TD, et al. (February 2007). "Global reconstruction of the human metabolic network based on genomic and bibliomic data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (6): 1777–82. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.1777D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610772104. PMC 1794290. PMID 17267599.

- ^ Goh KI, Cusick ME, Valle D, Childs B, Vidal M, Barabási AL (May 2007). "The human disease network". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (21): 8685–90. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8685G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701361104. PMC 1885563. PMID 17502601.

- ^ Lee DS, Park J, Kay KA, Christakis NA, Oltvai ZN, Barabási AL (July 2008). "The implications of human metabolic network topology for disease comorbidity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (29): 9880–5. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9880L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802208105. PMC 2481357. PMID 18599447.