Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Female body shape

View on Wikipedia

Female body shape or female figure is the cumulative product of a woman's bone structure along with the distribution of muscle and fat on the body.

Female figures are typically narrower at the waist than at the bust and hips. The bust, waist, and hips are called inflection points, and the ratios of their circumferences are used to define basic body shapes.

Reflecting the wide range of individual beliefs on what is best for physical health and what is preferred aesthetically, there is no universally acknowledged ideal female body shape. Ideals may also vary across different cultures, and they may exert influence on how a woman perceives her own body image.[1]

Physiology

[edit]Impact of estrogens

[edit]Estrogens, which are primary female sex hormones, have a significant impact on a female's body shape. They are produced in both men and women, but their levels are significantly higher in women, especially in those of reproductive age. Besides other functions, estrogens promote the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, such as breasts and hips.[2][3][4] As a result of estrogens, during puberty, girls develop breasts and their hips widen. Working against estrogen, the presence of testosterone in a pubescent female inhibits breast development and promotes muscle and facial hair development.[5]

Estrogen levels also rise significantly during pregnancy. A number of other changes typically occur during pregnancy, including enlargement and increased firmness of the breasts, mainly due to hypertrophy of the mammary gland in response to the hormone prolactin. The size of the nipples may increase noticeably. These changes may continue during breastfeeding. Breasts generally revert to approximately their previous size after pregnancy, although there may be some increased sagging.[6][7]

Breasts can decrease in size at menopause if estrogen levels decline.[8][9]

Fat distribution

[edit]

Estrogens can also affect the female body shape in a number of other ways, including increasing fat stores, accelerating metabolism, reducing muscle mass, and increasing bone formation.[10][11][12]

Estrogens cause higher levels of fat to be stored in a female body than in a male body.[13][14] They also affect body fat distribution,[15] causing fat to be stored in the buttocks, thighs, and hips in women,[16][17] but generally not around their waists, which will remain about the same size as they were before puberty. The hormones produced by the thyroid gland regulate the rate of metabolism, controlling how quickly the body uses energy, and controls how sensitive the body should be to other hormones. Body fat distribution may change from time to time, depending on food habits, activity levels and hormone levels.[18][19][20]

When women reach menopause and the estrogen produced by ovaries declines, fat migrates from their buttocks, hips and thighs to their waists;[21] later fat is stored at the abdomen.[22]

Body fat percentage recommendations are higher for females, as this fat may serve as an energy reserve for pregnancy. Males have less subcutaneous fat in their faces due to the effects of testosterone;[23][24] testosterone also reduces fat by aiding fast metabolism. The lack of estrogen in males generally results in more fat being deposited around the waist and abdomen (producing an "apple shape").[25]

Muscles

[edit]Testosterone is a steroid hormone which helps build and maintain muscles for physical activity, such as exercise. The amount of testosterone produced varies from one individual to another, but, on average, an adult female produces around one-eighth of the testosterone of an adult male,[26] but females are more sensitive to the hormone.[27]

Changes to body shape

[edit]The aging process has an inevitable impact on a person's body shape. A woman's sex hormone levels will affect the fat distribution on her body. According to Dr. Devendra Singh, "Body shape is determined by the nature of body fat distribution that, in turn, is significantly correlated with women's sex hormone profile, risk for disease, and reproductive capability."[28] Concentrations of estrogen will influence where body fat is stored.[29]

Before puberty both males and females have a similar waist–hip ratio.[28] At puberty, a girl's sex hormones, mainly estrogen, will promote breast development and a wider pelvis that is tilted forward, and until menopause a woman's estrogen levels will cause her body to store excess fat in the buttocks, hips and thighs,[29][30] but generally not around her waist, which will remain about the same size as it was before puberty. These factors result in women's waist–hip ratio (WHR) being lower than for males, although males tend to have a greater upper-body to waist–hip ratio (WHR) giving them a V shape look because of their greater muscle mass (e.g., they generally have much larger, more muscular and broader shoulders, pectoral muscles, teres major muscles and latissimus dorsi muscles).

During and after pregnancy, a woman experiences body shape changes. After menopause, with the reduced production of estrogen by the ovaries, there is a tendency for fat to redistribute from a female's buttocks, hips and thighs to her waist or abdomen.[21]

The breasts of girls and women in early stages of development commonly are "high" and rounded, dome- or cone-shaped, and protrude almost horizontally from a female's chest wall. Over time, the sag on breasts tends to increase due to their natural weight, the relaxation of support structures, and aging.

Categorisation in fashion industry

[edit]Body shapes are often categorised in the fashion industry into one of four elementary geometric shapes,[31] though there are very wide ranges of actual sizes within each shape:

Rectangular

- The waist is less than 9 inches (23 cm) smaller than the hips and bust.[31] Body fat is distributed predominantly in the abdomen, buttocks, chest, and face. This overall fat distribution creates the typical ruler (straight) shape.

Inverted triangle

- The shoulders are broader than the hips.[31] The legs and thighs tend to be slim, while the chest looks larger compared with the rest of the body. Fat is mainly distributed in the chest and face.

Spoon

- The hips are wider than the bust.[31] The distribution of fat varies, with fat tending to deposit first in the buttocks, hips, and thighs. As body fat percentage increases, an increasing proportion of body fat is distributed around the waist and upper abdomen. The women of this body type tend to have a relatively larger rear, thicker thighs, and a small(er) bosom. Also known as a "pear" shape.

Hourglass

- The hips and bust are almost of equal size, and the waist is narrower than both.[31] Body fat distribution tends to be around both the upper body and lower body.

A study of the shapes of over 6,000 women, carried out by researchers at the North Carolina State University circa 2005,[32] for apparel, found that 46% were rectangular, just over 20% spoon, just under 14% inverted triangle, and 8% hourglass.[31] Another study has found "that the average woman's waistline had expanded by six inches since the 1950s" and that women in 2004 were taller and had bigger busts and hips than those of the 1950s.[31] Note however that a 2021 study found that slight changes in measurement placement definition can recategorise up to 40% of women into different body shapes, meaning cross-research comparisons may be flawed unless the exact measurement definitions are used.[33][34]

Several similar classifications of women's body shape exist. These include:[35]

- Sheldon: "Somatotype: {Plumper: Endomorph, Muscular: Mesomorph, Slender: Ectomorph}", 1940s[36]

- Douty's "Body Build Scale: {1,2,3,4,5}", 1968

- Bonnie August's "Body I.D. Scale: {A,X,H,V,W,Y,T,O,b,d,i,r}", 1981

- Simmons, Istook, & Devarajan "Female Figure Identification Technique (FFIT): {Hourglass, Bottom Hourglass, Top Hourglass, Spoon, Rectangle, Diamond, Oval, Triangle, Inverted Triangle}", 2002

- Connell's "Body Shape Assessment Scale: {Hourglass, Pear, Rectangle, Inverted Triangle}", 2006

- Rasband: {Ideal, Triangular, Inverted Triangular, Rectangular, Hourglass, Diamond, Tubular, Rounded}, 2006

- Lee JY, Istook CL, Nam YJ, "Comparison of body shape between USA and Korean women: {Hourglass, Bottom Hourglass, Top Hourglass, Spoon, Triangle, Inverted Triangle, Rectangle}", 2007.

FFIT for Apparel measurements

[edit]The "Female Figure Identification Technique for Apparel" uses the following formula to identify an individual's body type:[37]

- Hourglass

- If (bust − hips) ≤ 1 in (25 mm) AND (hips − bust) < 3.6 in (91 mm) AND ((bust − waist) ≥ 9 in (230 mm) OR (hips − waist) ≥ 10 in (250 mm) )

- Bottom hourglass

- If (hips − bust) ≥ 3.6 in (91 mm) AND (hips − bust) < 10 in (250 mm) AND (hips − waist) ≥ 9 in (230 mm) AND (high hip/waist) < 1.193

- Top hourglass

- If (bust − hips) > 1 in (25 mm) AND (bust − hips) < 10 in (250 mm) AND (bust − waist) ≥ 9 in (230 mm)

- Spoon

- If (hips − bust) > 2 in (51 mm) AND (hips − waist) ≥ 7 in (180 mm) AND (high hip/waist) ≥ 1.193

- Triangle

- If (hips − bust) ≥ 3.6 in (91 mm) AND (hips − waist) < 9 in (230 mm)

- Inverted triangle

- If (bust − hips) ≥ 3.6 in (91 mm) AND (bust − waist) < 9 in (230 mm)

- Rectangle

- If (hips − bust) < 3.6 in (91 mm) AND (bust − hips) < 3.6 in (91 mm) AND (bust − waist) < 9 in (230 mm) AND (hips − waist) < 10 in (250 mm)

Clothing standards

[edit]Some clothing size standards define categories.[38]

Inverted triangle-rectangular categories

[edit]The Chinese clothing size standards give codes to clothing designed for different ratios between chest and waist. They adapt for a linear scale between inverted triangle/hourglass and rectangular.

| Shape Code | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| Y | 19–24 cm | 17–22 cm |

| A | 14–18 cm | 12–16 cm |

| B | 9–13 cm | 7–11 cm |

| C | 4–8 cm | 2–6 cm |

Rectangular-spoon categories

[edit]The Japanese and South Korean clothing size standards give codes to women's clothing designed for different ratios between hips and chest. The German standards similarly use hip and bust measures. They all adapt for a linear scale between rectangular and spoon shapes.

| Shape Code | Female |

|---|---|

| Y | 0 cm |

| A | 4 cm |

| AB | 8 cm |

| B | 12 cm |

| Shape Code | Female |

|---|---|

| H | 0–3 cm |

| N | 3–9 cm |

| A | 9–12 cm |

| Shape Code | Female |

|---|---|

| S | -4–2 cm |

| M | 2–8 cm |

| L | 8+ cm |

The German sizing system also has height categories for short, regular and tall women, which combine with the shape categories to produce 9 categories.

Proportions and dimensions

[edit]The circumferences of bust, waist, and hips (BWH) and the ratios between them are a widespread method of identifying different female body shapes. As noted above, descriptive terms used include "rectangle", "spoon", "inverted triangle", and "hourglass".[31]

The waist is typically smaller than the bust and hips, unless there is a high proportion of body fat distributed around it. How much the bust or hips inflect inward, towards the waist, determines a woman's structural shape. The hourglass shape is present in only about 8% of women.[31]

A woman's dimensions are often expressed by the circumference around the three inflection points. For example, "36–29–38" in US customary units would mean a 36 in (91 cm) bust, 29 in (74 cm) waist and 38 in (97 cm) hips.

Height will also affect the appearance of the figure. A woman who is 36–24–36 (91–61–91 cm) at 5 ft 2 in (1.57 m) height will look different from a woman who is 36–24–36 at 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) height. If both are the same weight, the taller woman has a much lower body mass index; if they have the same BMI, the weight is distributed around a greater volume.

A woman's bust measure is a combination of her rib cage and breast size. For convenience, a woman's bra measurements are often used as a proxy. Conventionally, measurement for the band of a bra is taken around the torso immediately below the breasts, with the tape measure parallel to the floor.[39][40] Bra cup size is determined by measuring across the crest of the breasts and calculating the difference between that measurement and the band measurement.[39][41] The waist is measured at the midpoint between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the 'front' hip bones. The hips are measured at the largest circumference of the hips and buttocks.[42]

Fashion models

[edit]The British Fashion Model Agents Association (BFMA) says that female models should be at least 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) tall and proportionately around 34–24–34" (86–61–86 cm).[43] Laws "aimed at preventing anorexia by stopping the promotion of inaccessible ideals of beauty" have been introduced in a number of European countries,[44] to regulate the minimum actual or apparent BMI of fashion models. "Under World Health Organisation guidelines an adult with a BMI below 18.5 is considered underweight, 18 malnourished, and 17 severely malnourished. The average model measuring 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) and weighing 50 kg (110 lb; 7 st 12 lb) has a BMI of 16".[44]

Cultural perceptions

[edit]According to Camille Paglia, the ideal body type as envisioned by members of society has changed throughout history. She states that Stone Age Venus figurines show the earliest body type preference, dramatic steatopygia; and that the emphasis on protruding belly, breasts, and buttocks is likely a result of both the aesthetic of being well fed and aesthetic of being fertile, traits that were more difficult to achieve at the time. In sculptures from Classical Greece and Ancient Rome the female bodies are more tubular and regularly proportioned.[45]: 5 There is essentially no emphasis given to any particular body part, not the breasts, buttocks, or belly.

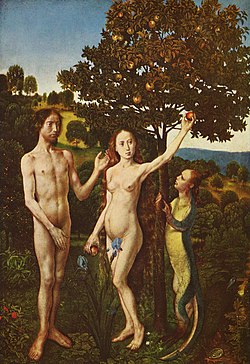

Moving forward there is more evidence that fashion somewhat dictated what people believed were the proper female body proportions. This is the case because the body is primarily seen through clothing, which always changes the way the underlying structures are conceived.[46]: xii–xiii The first representations of truly fashionable women appear in the 14th century.[46]: 90 Between the 14th and 16th centuries in northern Europe, bulging bellies were again desirable, however the stature of the rest of the figure was generally thin. This is most easily visible in paintings of nudes from the time. When looking at clothed images, the belly is often visible through a mass of otherwise concealing, billowing, loose robes. Since the stomach was the only visible anatomical feature, it became exaggerated in nude depictions while the rest of the body remained minimal.[46]: 96–100, 106 In southern Europe, around the time of the renaissance, this was also true. Though the classical aesthetic was being revived and very closely studied, the art produced in the time period was influenced by both factors. This resulted in a beauty standard that reconciled the two aesthetics by using classically proportioned figures who had non-classical amounts of flesh and soft, padded skin.[46]: 96–98, 104

In the nude paintings of the 17th century, such as those by Rubens, the naked women appear quite plump. Upon closer inspection however, most of the women have fairly normal statures, Rubens has simply painted their flesh with rolls and ripples that otherwise would not be there. This may be a reflection of the female style of the day: a long, cylindrical, gown with rippling satin accents, tailored over a figure in stays. Thus Rubens' women have a tubular body with rippling embellishments.[46]: 106, 316 While stays continued to be fashionable into the 18th century, they were shortened, became more conical, and consequently began to emphasize the waist. It also lifted and separated the breasts as opposed to the 17th century corsets which compressed and minimized the breasts. Consequently, depictions of nude women in the 18th century tend to have a very narrow waist and high, distinct breasts, almost as if they were wearing an invisible corset.[46]: 91, 112–116 La maja desnuda is a clear example of this aesthetic. The 19th century maintained the general figure of the 18th century. Examples can be seen in the works of many contemporary artists, both academic artists, such as Cabanel, Ingres, and Bouguereau, and Impressionists, such as Degas, Renoir, and Toulouse-Lautrec. As the 20th century began, the rise of athletics resulted in a drastic slimming of the female figure. This culminated in the 1920s flapper look, which has informed modern fashion ever since.[45]: 4 [46]: 152

The last 100 years envelop the time period in which that overall body type has been seen as attractive, though there have been small changes within the period as well. The 1920s was the time in which the overall silhouette of the ideal body slimmed down. There was dramatic flattening of the entire body resulting in a more youthful aesthetic.[46]: 150–153 As the century progressed, the ideal size of both the breasts and buttocks increased. From the 1950s to 1960 that trend continued with the interesting twist of cone shaped breasts as a result of the popularity of the bullet bra. In the 1960s, the invention of the miniskirt as well as the increased acceptability of pants for women, prompted the idealization of the long leg that has lasted to this day.[46]: 93–95 Following the invention of the push-up bra in the 1970s the ideal breast has been a rounded, fuller, and larger breast. In the past 20 years the average American bra size has increased from 34B to 34DD,[47] although this may be due to the increase in obesity within the United States in recent years. Additionally, the ideal figure has favored an ever-lower waist–hip ratio, especially with the advent and progression of digital editing software such as Adobe Photoshop.[45]: 4, 6–7

Social and health issues

[edit]

Each society develops a general perception of what an ideal female body shape would be like. These ideals are generally reflected in the art and literature produced by or for a society, as well as in popular media such as films and magazines. The ideal or preferred female body size and shape has varied over time and continues to vary among cultures;[48][49] but a preference for a small waist has remained fairly constant throughout history.[50] A low waist–hip ratio has often been seen as a sign of good health and reproductive potential.[51]

A low waist–hip ratio has also often been regarded as an indicator of attractiveness of a woman, but recent research suggests that attractiveness is more correlated to body mass index than waist–hip ratio, contrary to previous belief.[52][53] According to Dr. Devendra Singh of the University of Texas, who studied the representations of women, historically found there was a trend for slightly overweight women in the 17th and 18th centuries, as typified by the paintings of Rubens, but that in general there has been a preference for a slimmer waist in Western culture. He notes that "The finding that the writers describe a small waist as beautiful suggests instead that this body part—a known marker of health and fertility—is a core feature of feminine beauty that transcends ethnic differences and cultures."[50]

New research suggests that apple-shaped women have the highest risk of developing heart disease, while hourglass-shaped women have the lowest.[54] Diabetes professionals advise that a waist measurement for a woman of over 80 cm (31 in) increases the risk of heart disease, but that ethnic background also plays a factor.[55]

Waist–hip ratio

[edit]

Compared to males, females generally have relatively narrow waists and large buttocks,[56] and this along with wide hips make for a wider hip section and a lower waist–hip ratio.[57] Research shows that a waist–hip ratio (WHR) for a female very strongly correlates to the perception of attractiveness.[58] Women with a 0.7 WHR (waist circumference that is 70% of the hip circumference) are rated more attractive by men in various cultures.[28] Such diverse beauty icons as Marilyn Monroe, Sophia Loren and the Venus de Milo have ratios around 0.7;[59] this is a typical ratio in Western art.[60] In other cultures, preferences vary,[61] ranging from 0.6 in China,[62] to 0.8 or 0.9 in parts of South America and Africa,[63][64][65] and divergent preferences based on ethnicity, rather than nationality, have also been noted.[66][67]

Anthropologists and behaviorists have discovered evidence that the WHR is a significant measure for female attractiveness.[68][69]

Many studies indicate that WHR correlates with female fertility, leading some to speculate that its use as a sexual selection cue by men has an evolutionary basis.[70] However it is also suggested that the evident relationships between WHR-influencing hormones and survival-relevant traits such as competitiveness and stress tolerance may give a preference for higher waist–hip ratios its own evolutionary benefit. That, in turn, may account for the cross-cultural variation observed in actual average waist–hip ratios and culturally preferred waist-to-hip ratios for women.[71]

WHR has been found to be a more efficient predictor of mortality in older people than waist circumference or body mass index (BMI).[72]

Waist-height ratio

[edit]A person's "waist-height ratio" (WHtR), is defined as their waist circumference divided by their height, both measured in the same units. It is used as a predictor of obesity-related cardiovascular disease. The WHtR is a measure of the distribution of body fat. Higher values of WHtR indicate higher risk of obesity-related cardiovascular diseases; it is correlated with abdominal obesity.[73] In September 2022, the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (a government body) announced new guidelines which suggested that all adults "ensure their waist size is less than half their height in order to help stave off serious health problems".[74][75] This guideline is independent of gender.

Bodies as identity

[edit]Over the past several hundred years, there has been a shift towards viewing the body as part of one's identity – not in a purely physical way, but as a means of deeper self-expression. David Gauntlett, in his 2008 book, recognizes the importance of malleability in physical identity, stating, "the body is the outer expression of our self, to be improved and worked upon".[76] One of the more key factors in creating the desire for a particular body shape – most notably for women – is the media, which has promoted a number of so-called "ideal" body shapes.[77] Fashionable figures are often unrealistic and unattainable for much of the population, and their popularity tends to be short-lived due to their arbitrary nature.[78][79]

During the 1950s, the fashion model and celebrity were two separate entities, allowing the body image of the time to be shaped more by television and film rather than high fashion advertisements. While the fashion model of the 1950s, such as Jean Patchett and Dovima, were very thin, the ideal image of beauty was still a larger one. As the fashion houses in the early 1950s still catered to a specific, elite clientele, the image of the fashion model at that time was not as sought after or looked up to as was the image of the celebrity. While the models that graced the covers of Vogue Magazine and Harper's Bazaar in the 1950s were in line with the thin ideal of the day, the most prominent female icon was Marilyn Monroe. Monroe, who was more curvaceous, fell on the opposite end of the feminine ideal spectrum in comparison to high fashion models. Regardless of their sizes, however, both fashion of the time and depictions of Monroe emphasize a smaller waist and fuller bottom half. The late 1950s, however, brought about the rise of ready-to-wear fashion, which implemented a standardized sizing system for all mass-produced clothing. While fashion houses, such as Dior and Chanel, remained true to their couture, tailor-made garments, the rise of these rapidly-produced, standardized garments led to a shift in location from Europe to America as the epicenter of fashion. Along with that shift came the standardization of sizes, in which garments were not made to fit the body anymore, but instead the body must be altered to fit the garment.[80]

During the 1960s, the popularity of the model Twiggy meant that women favoured a thinner body, with long, slender limbs.[81] This was a drastic change from the former decade's ideal, which saw curvier icons, such as Marilyn Monroe, to be considered the epitome of beautiful. These shifts in what was seen to be the "fashionable body" at the time followed no logical pattern, and the changes occurred so quickly that one shape was never in vogue for more than a decade. As is the case with fashion itself in the post-modern world, the premise of the ever-evolving "ideal" shape relies on the fact that it will soon become obsolete, and thus must continue changing to prevent itself from becoming uninteresting.[82]

An early example of the body used as an identity marker occurred in the Victorian era, when women wore corsets to help themselves attain the body they wished to possess.[83] Having a tiny waist was a sign of social status, as the wealthier women could afford to dress more extravagantly and sport items such as corsets to increase their physical attractiveness.[84] By the 1920s, the cultural ideal had changed significantly as a result of the suffrage movement, and "the fashion was for cropped hair, flat (bound) breasts and a slim, androgynous shape".[85]

More recently, magazines and other popular media have been criticized for promoting an unrealistic trend of thinness. David Gauntlett states that the media's "repetitive celebration of a beauty 'ideal' which most women will not be able to match … will eat up readers' time and money—and perhaps good health—if they try".[86] Additionally, the impact that this has on women and their self-esteem is often a very negative one,[87] and resulted in the diet industry taking off in the 1960s – something that would not have occurred "had bodily appearance not been so closely associated with identity for women".[88] Melissa Oldman states, "Nowhere is the thin female ideal more evident than in popular media."[89]

The importance of "the body as a work zone", as Myra MacDonald asserts, further perpetuates the link between fashion and identity, with the body being used as a means of creating a visible and unavoidable image for oneself.[90] The tools with which to create the final copy of such a project range from the extreme—plastic surgery—to the more tame, such as diet and exercise.[91]

Alteration of body shape

[edit]A study at Brigham Young University using MRI technology suggested that women experience more anxiety about weight gain than do men,[92] while aggregated research has been used to claim that images of thin women in popular media may induce psychological stress.[93] A study of 52 older adults found that females may think more about their body shape and endorse thinner figures than men even into old age.[94]

Various strategies, including exercise, are sometimes employed in an attempt to temporarily or permanently alter the shape of a body. Dieting is also sometimes used, but is generally not effective in the long term.[95]

At times artificial devices are used or surgery is employed. In 2019, 92% of all cosmetic procedures in the US were undertaken by women, with the most popular being a breast augmentation.[96] Breast size can be artificially increased or decreased. Falsies, breast prostheses or padded bras may be used to increase the apparent size of a woman's breasts, while minimiser bras may be used to reduce the apparent size. Breasts can be surgically enlarged using breast implants or reduced by the systematic removal of parts of the breasts. Hormonal breast enhancement may be another option.[97][98][99]

Historically, boned corsets have been used to reduce waist sizes. The corset reached its climax during the Victorian era. In twentieth century these corsets were mostly replaced with more flexible/comfortable foundation garments. Where corsets are used for waist reduction, they may cause temporary reduction through occasional use or permanent reduction through constant and continuous use. Those who use corsets for permanent reduction are often referred to as tightlacers. Liposuction and liposculpture are common surgical methods for reducing the waist line.[100][101]

Padded control briefs or hip and buttock padding may be used to increase the apparent size of hips and buttocks. Buttock augmentation surgery may be used to increase the size of hips and buttocks to make them look more rounded.[102]

Social perceptions of the ideal woman's body

[edit]In a 2012 experiment, researchers Crossley, Cornelissen, and Tovée asked men and women to depict an attractive female body, and the majority of them chose the same ideal.[103] The women who participated in this experiment drew their ideal bodies with enlarged busts and narrowed the rest of their bodies. The male participants also depicted their ideal partner with the same image. The researchers state, "For both sexes, the primary predictor of female beauty is a relatively low BMI combined with a relatively curvaceous body".[103] However, the generality of their conclusions was limited given their small sample size and single ethnicity of participants.

See also

[edit]- Awoulaba – Woman epitomising West African beauty standards

- Body proportions – Proportions of the human body in art

- Artistic canons of body proportions – Criteria used in formal figurative art

- Chinese ideals of female beauty – Beauty standards within China or overseas Chinese communities

- Human variability – Range of possible values for any characteristic of human beings

- List of artists focused on the female form

- Physical attractiveness – Aesthetic assessment of physical traits

- Sex differences in humans – Difference between males and females

- Somatotype and constitutional psychology – Taxonomy to categorize human physiques

- Steatopygia – Human lower-body phenotype

References

[edit]- ^ Gordon, K.H.; Castro, Y.; Sitnikov, L.; Holm-Denoma, J.M. "Cultural body shape ideals and eating disorder symptoms among White, Latina, and Black college women". PsycNET /. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Hess, R. A.; Bunick, D; Lee, K. H.; Bahr, J; Taylor, J. A.; Korach, K. S.; Lubahn, D. B. (1997). "A role for estrogens in the male reproductive system". Nature. 390 (6659): 447–48. Bibcode:1997Natur.390..509H. doi:10.1038/37352. PMC 5719867. PMID 9393999.

- ^ Raloff, J. (6 December 1997). "Science News Online (12/6/97): Estrogen's Emerging Manly Alter Ego". Science News. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ "Science Blog – Estrogen Linked To Sperm Count, Male Fertility". Science Blog. Archived from the original on 7 May 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ "Normal Testosterone and Estrogen Levels in Women". Website. WebMD. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Motosko CC, Kalowitz Bieber A, Keltz Pomeranz M, Stein JA, Martires KJ. "Physiologic changes of pregnancy: A review of the literature". PMC 5715231.

- ^ Alex, A; Bhandary, E; McGuire, KP (2020). "Anatomy and Physiology of the Breast during Pregnancy and Lactation". Adv Exp Med Biol. 1252: 3–7. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-41596-9_1. PMID 32816256.

- ^ "How Menopause Affects Your Breasts". WebMD. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ Kim, Eun Young; Chang, Yoosoo; Ahn, Jiin; Yun, Ji-Sup; Park, Yong Lai; Park, Chan Heun; Shin, Hocheol; Ryu, Seungho (30 July 2020). "Menopausal Transition, Body Mass Index, and Prevalence of Mammographic Dense Breasts in Middle-Aged Women". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (8): 2434. doi:10.3390/jcm9082434. PMC 7465213. PMID 32751482.

- ^ Bjune, Jan-Inge; Strømland, Pouda Panahandeh; Jersin, Regine Åsen; Mellgren, Gunnar; Dankel, Simon Nitter (22 February 2022). "Metabolic and Epigenetic Regulation by Estrogen in Adipocytes". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 13 828780. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.828780. ISSN 1664-2392. PMC 8901598. PMID 35273571.

- ^ Hansen, Mette (1 February 2018). "Female hormones: do they influence muscle and tendon protein metabolism?". Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 77 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1017/S0029665117001951. ISSN 0029-6651.

- ^ Lizcano, Fernando (2022). "Roles of estrogens, estrogen-like compounds, and endocrine disruptors in adipocytes". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 13: 921504. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.921504. ISSN 1664-2392. PMC 9533025. PMID 36213285.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: article number as page number (link) - ^ "Tanita - Women & Body Fat". tanita.com. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2026.

- ^ "Sex hormone making women fat?". The Times Of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2026.

- ^ Mandal, Arpita; Das Chaudhuri, A.B. (2010). "Anthropometric - Hormonal Correlation: An Overview" (PDF). J Life Sci. 2 (2): 65–71. doi:10.1080/09751270.2010.11885154. S2CID 149016375.

body shape is determined by the nature of body fat distribution that, in turn, is significantly correlated with women's sex hormone profile

- ^ "Reduce Abdominal Fat From Stomach". www.annecollins.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2026.

- ^ Design, Foraker. "Waistline Worries: Turning Apples Back Into Pears". www.healthywomen.org. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2026.

- ^ "Thyroid Hormone Action and Energy Expenditure". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ Bjergved, Lena; Jørgensen, Torben; Perrild, Hans; Laurberg, Peter; Krejbjerg, Anne; Ovesen, Lars; Rasmussen, Lone Banke; Knudsen, Nils (11 April 2014). "Thyroid Function and Body Weight: A Community-Based Longitudinal Study". PLOS ONE. 9 (4) e93515. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...993515B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093515. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3984087. PMID 24728291.

- ^ Karkhaneh, Maryam; Qorbani, Mostafa; Ataie-Jafari, Asal; Mohajeri-Tehrani, Mohamad Reza; Asayesh, Hamid; Hosseini, Saeed (25 October 2019). "Association of thyroid hormones with resting energy expenditure and complement C3 in normal weight high body fat women". Thyroid Research. 12 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/s13044-019-0070-4. ISSN 1756-6614. PMC 6813955. PMID 31666810.

- ^ a b Andrews, Michelle (12 January 2006). "A Matter of Fat". Yahoo. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007.

Researchers think that the lack of estrogen at menopause plays a role in driving our fat northward

- ^ Solan, Matthew (1 October 2023). "An inside look at body fat". Harvard Health. Retrieved 7 February 2026.

- ^ "Subcutaneous fat in face decreases" – Advanced postnatal effects

- ^ Admin (30 July 2019). "Jawlines: Understanding Gender Differences, Facial Ageing and Defining". ifaas. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "What It Means to Have an Apple-Shaped Body". Nina Cherie Franklin. 2 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ Torjesen PA, Sandnes L (March 2004). "Serum testosterone in women as measured by an automated immunoassay and a RIA". Clinical Chemistry. 50 (3): 678, author reply 678–9. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2003.027565. PMID 14981046.

- ^ Dabbs M, Dabbs JM (2000). Heroes, rogues, and lovers: testosterone and behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-135739-5.

- ^ a b c Singh, Devendra (Spring 2006). "An Evolutionary Theory of Female Physical Attractiveness". Eye on Psi Chi. 10 (3). Chattanooga, TN: Psi Chi: 18–19, 28–31. doi:10.24839/1092-0803.Eye10.3.18. S2CID 31804468.

- ^ a b Collins, Anne. "Reduce Abdominal Fat". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ Peeke, Pamela M. (15 November 2008). "Waistline Worries: Turning Apples Back into Pears". National Women's Health Resource Center. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McCormack, Helen (21 November 2005). "The shape of things to wear: scientists identify how women's figures have changed in 50 years". The Independent. UK.

How female body shapes have changed over time. - ^ Istook, C; Simmons, K; Devarajan, P. "Female Figure Identification Technique (FFIT) for Apparel" (PDF). International Foundation of Fashion Technology institutes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Parker, Christopher J.; Hayes, Steven George; Brownbridge, Kathryn; Gill, Simeon (12 April 2021). "Assessing the female figure identification technique's reliability as a body shape classification system". Ergonomics. 64 (8): 1035–1051. doi:10.1080/00140139.2021.1902572. ISSN 0014-0139. PMID 33719914. S2CID 232231822.

- ^ "Why you might not be the body shape you think". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Sidberry, Phillip Anthony. "Effects of Body Shape on Body Cathexis and Dress Shape Preferences of Female Consumers: A Balancing Perspective" (PDF). auburn.edu. Auburn University. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ "Body Type Diet: Are You an Ectomorph, Mesomorph, or Endomorph?". everydayhealth.com. Retrieved 7 February 2026.

- ^ Yim Lee, Jeong; Istook, Cynthia L.; Ja Nam, Yun; Mi Park, Sun (1 January 2007). "Comparison of body shape between USA and Korean women". International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology. 19 (5): 374–391. doi:10.1108/09556220710819555. ISSN 0955-6222.

- ^ Chun, J. (1 January 2014). "10 - International apparel sizing systems and standardization of apparel sizes". Anthropometry, Apparel Sizing and Design. Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles. Woodhead Publishing: 274–304. doi:10.1533/9780857096890.2.274. ISBN 978-0-85709-681-4.

- ^ a b "Find Your Bra Size". Bare Necessities. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ "How to Measure Bra Size". Women's Health Magazine (online). Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Edmark, Tomima. How to Measure for Bra. HerRoom.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ "Waist Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio, Report of a WHO Expert Consultation" (PDF). World Health Organization. 8–11 December 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ "Do I have what it takes to be a model?". British Fashion Model Agents Association.

- ^ a b Gayle, Damien (6 May 2017). "Fashion models in France need doctor's note before taking to catwalk". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Paglia, Camille. "The Cruel Mirror". Art Documentation. 23: 4–7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hollander, Anne (1993). Seeing Through Clothes. California: University of California Press. pp. 83–156.

- ^ Dicker, Ron (24 July 2013). "American Bra Size Average Increases From 34B to 34DD in Just 20 Years, Survey Says". HuffPost. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ "Ideal weight varies across cultures, but body image dissatisfaction pervades". physorg.com. 23 October 2007.

- ^ Rob Kemp. "Sir Mix-a-Lot 'Baby Got Back' Video Oral History – Vulture". Vulture.

- ^ a b "Slim waist holds sway in history". BBC News. 10 January 2007.

- ^ Khamsi, Roxanne (10 January 2007). "The hourglass figure is truly timeless". NewScientist.com news service.

- ^ Tovee M.J.; Maisey D.S.; Emery J.L.; Cornelissen P.L. (22 January 1999). "Visual cues to female physical attractiveness". Proc Biol Sci. 266 (1415): 211–18. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0624. PMC 1689653. PMID 10097394.

- ^ Wilson, Jan M. B.; Tripp, Dean A.; Boland, Fred J. (3 December 2005). "The relative contributions of waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index to judgments of attractiveness – Sexualities, Evolution & Gender". Sexualities, Evolution & Gender. 7 (3): 245–67. doi:10.1080/14616660500238769.

- ^ "Curvier women 'will live longer". BCC News. 3 June 2005.

- ^ Walker, Rosemary; Rodgers, Jill (2006). Type 2 Diabetes – Your Questions Answered. Dorling Kindersley Australasia. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-74033-550-8.

- ^ "Big butts are back"article Archived 16 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Cosmopolitan

- ^ "Why men store fat in bellies, women on hips". The Times of India.

- ^ Buss, David (2003) [1994]. The Evolution of Desire (hardcover) (second ed.). New York: Basic Books. pp. 55, 56. ISBN 978-0-465-07750-2.

- ^ Million Dollar Body Club. "BMI and Waist–hip Ratio: The Magic Number for Health and Beauty". Focused on Fitness. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007.

- ^ Bovet, Jeanne; Raymond, Michel (17 April 2015). "Preferred Women's Waist-to-Hip Ratio Variation over the Last 2,500 Years". PLOS ONE. 10 (4) e0123284. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1023284B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123284. PMC 4401783. PMID 25886537. cited in Stephen Heyman (27 May 2015). "Gleaning New Perspectives by Measuring Body Proportions in Art". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Fisher, M.L.; Voracek M. (June 2006). "The shape of beauty: determinants of female physical attractiveness". J Cosmet Dermatol. 5 (2): 190–94. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2006.00249.x. PMID 17173598. S2CID 25660426.

- ^ Dixson, B.J.; Dixson A.F.; Li B.; Anderson M.J. (January 2007). "Studies of human physique and sexual attractiveness: sexual preferences of men and women in China". Am J Hum Biol. 19 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20584. PMID 17160976. S2CID 8868828.

- ^ Marlowe, F.; Wetsman, A. (2001). "Preferred waist-to-hip ratio and ecology" (PDF). Personality and Individual Differences. 30 (3): 481–89. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.489.4169. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00039-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ Marlowe, F.W.; Apicella, C.L.; Reed, D. (2005). "Men's Preferences for Women's Profile Waist–Hip-Ratio in Two Societies" (PDF). Evolution and Human Behavior. 26 (6): 458–68. Bibcode:2005EHumB..26..458M. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.07.005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ Dixson, B.J.; Dixson A.F.; Morgan B.; Anderson M.J. (June 2007). "Human physique and sexual attractiveness: sexual preferences of men and women in Bakossiland, Cameroon". Arch Sex Behav. 36 (3): 369–75. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9093-8. PMID 17136587. S2CID 40115821.

- ^ Freedman, R.E.; Carter M.M.; Sbrocco T.; Gray JJ. (August 2007). "Do men hold African-American and Caucasian women to different standards of beauty?". Eat Behav. 8 (3): 319–33. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.11.008. PMC 3033406. PMID 17606230.

- ^ Freedman, R.E.; Carter M.M.; Sbrocco T.; Gray J.J. (July 2004). "Ethnic differences in preferences for female weight and waist-to-hip ratio: a comparison of African-American and White American college and community samples". Eat Behav. 5 (3): 191–98. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.01.002. PMID 15135331.

- ^ Singh D (August 1993). "Adaptive significance of female physical attractiveness: role of waist-to-hip ratio". J Pers Soc Psychol. 65 (2): 293–307. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.492.9539. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.293. PMID 8366421.

- ^ Singh, Devendra; Young, Robert K. (27 June 2001). "Body Weight, Waist-to-Hip Ratio, Breasts, and Hips: Role in Judgments of Female Attractiveness and Desirability for Relationships" (PDF). Ethology and Sociobiology. 16 (6): 483–507. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(95)00074-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2011.

- ^ Buss, David (2003) [1994]. The Evolution of Desire (hardcover) (second ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-465-07750-2.

- ^ Cashdan, Elizabeth (December 2008). "Waist-to-Hip Ratios Across Cultures: Trade-Offs Between Androgen- and Estrogen-Dependent Traits". Current Anthropology. 49 (6): 1099–1107. doi:10.1086/593036. JSTOR 10.1086/593036. S2CID 146460260.

- ^ "Waist–hip Ratio Should Replace Body Mass Index As Indicator of Mortality Risk in Older People". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 12 August 2006.

- ^ Lee CM, Huxley RR, Wildman RP, Woodward M (July 2008). "Indices of abdominal obesity are better discriminators of cardiovascular risk factors than BMI: a meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 61 (7): 646–653. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.012. PMID 18359190.

- ^ Gregory, Anderew (8 April 2022). "Ensure waist size is less than half your height, health watchdog says". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ "Obesity: identification, assessment and management | Clinical guideline [CG189]". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 8 September 2022. Recommendations 1.2.11 and 1.2.12

- ^ Gauntlett, p. 113

- ^ Holland, Samantha (2004). Alternative femininities: body, age and identity. New York City: Berg Publishers, Ltd.

- ^ Ngo, Nealie Tan (1 October 2019). "What Historical Ideals of Women's Shapes Teach Us About Women's Self-Perception and Body Decisions Today". AMA Journal of Ethics. 21 (10): 879–901. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2019.879. ISSN 2376-6980. PMID 31651388.

- ^ "Unrealistic beauty standards cost U.S. economy billions each year". News. 7 October 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Sypeck, M. F.; Gray, J. J.; Ahrens, A. H. (2004). "No longer just a pretty face: Fashion magazines' depictions of ideal female beauty from 1959 to 1999". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 36 (3): 342–7. doi:10.1002/eat.20039. PMID 15478132.

- ^ MacDonald

- ^ Miles, Steven (1998). Consumerism as a Way of Life. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- ^ Bovey, Shelley (1994). The Forbidden Body. Glasgow: Pandora Press. ISBN 978-0-04-440871-0.

- ^ Barford, Vanessa (19 June 2012). "The re-re-re-rise of the corset". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Bovey, Shelley (1994). The Forbidden Body. Glasgow: Pandora Press. pp. 176. ISBN 978-0-04-440871-0.

- ^ Gauntlett, p. 200

- ^ Gauntlett, p. 201

- ^ MacDonald, p. 201

- ^ Oldham, Melissa (2017). "How the media shapes our cultural ideals of body shape". Culture Matters.

- ^ MacDonald, p. 202

- ^ Gauntlett

- ^ "Fear of getting fat seen in healthy women's brain scans". 13 April 2010. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "Skinny celebs a health hazard". The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Ferraro, F. Richard; Muehlenkamp, Jennifer J; Paintner, Ashley; Wasson, Kayla; Hager, Tracy; Hoverson, Fallon (October 2008). "Aging, Body Image, and Body Shape". Journal of General Psychology. 135 (4): 379–392, 14p. doi:10.3200/GENP.135.4.379-392. PMID 18959228. S2CID 37023505.

- ^ Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew AM, Samuels B, Chatman J (April 2007). "Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer". The American Psychologist. 62 (3): 220–233. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.666.7484. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.62.3.220. PMID 17469900.

In sum, there is little support for the notion that diets ["severely restricting one's calorie intake"] lead to lasting weight loss or health benefits.

- ^ "Plastic Surgery Statistics". American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Gunther Göretzlehner; Christian Lauritzen; Thomas Römer; Winfried Rossmanith (2012). Praktische Hormontherapie in der Gynäkologie. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 385–. ISBN 978-3-11-024568-4.

- ^ R.E. Mansel; Oystein Fodstad; Wen G. Jiang (2007). Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 217–. ISBN 978-1-4020-5866-0.

- ^ Hartmann BW, Laml T, Kirchengast S, Albrecht AE, Huber JC (1998). "Hormonal breast augmentation: prognostic relevance of insulin-like growth factor-I". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 12 (2): 123–27. doi:10.3109/09513599809024960. PMID 9610425.

- ^ "Liposuction NYC | Mount Sinai - New York". Mount Sinai Health System. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Zhang, Yi Xin; Lazzeri, Davide; Grassetti, Luca; Silvestri, Alessandro; Trisliana Perdanasari, Aurelia; Han, Sheng; Torresetti, Matteo; di Benedetto, Giovanni; Castello, Manuel Francisco (6 February 2015). "Three-dimensional Superficial Liposculpture of the Hips, Flank, and Thighs". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open. 3 (1): e291. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000000241. ISSN 2169-7574. PMC 4323395. PMID 25674372.

- ^ "Buttock Enhancement Procedures NYC | Mount Sinai - New York". Mount Sinai Health System. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ a b Crossley, Kara L.; Cornelissen, Piers L.; Tovée, Martin J. (29 November 2012). "What Is an Attractive Body? Using an Interactive 3D Program to Create the Ideal Body for You and Your Partner". PLOS ONE. 7 (11) e50601. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750601C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050601. PMC 3510069. PMID 23209791.

Cited sources

[edit]- Gauntlett, David (2008). Media, gender, and identity. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-18960-6.

- MacDonald, Myra (1995). Representing Women: Myths of Femininity in the Popular Media. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-63221-5.

External links

[edit]- Art and love in Renaissance Italy, Issued in connection with an exhibition held Nov 2008–Feb 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (see Belle: Picturing Beautiful Women; pp. 246–254)

Female body shape

View on GrokipediaBiological and Physiological Foundations

Hormonal and Genetic Influences

Estrogen, the primary female sex hormone, plays a central role in directing fat deposition toward subcutaneous regions such as the hips, thighs, and breasts, resulting in the characteristic gynoid body shape during reproductive years.[6] [8] This distribution contrasts with the android pattern more common in males, where testosterone promotes visceral fat accumulation around the abdomen.[9] During puberty, rising estrogen levels trigger skeletal changes including pelvic widening to accommodate potential childbirth, alongside increased fat mass acquisition—females gain significantly more fat relative to fat-free mass compared to males.[10] [11] Progesterone and other hormones modulate these effects, but estrogen deficiency, as occurs post-menopause, shifts fat toward visceral depots, elevating waist circumference and altering overall shape toward a more centralized pattern.[12] [13] Cross-sex hormone therapy in transgender women, involving estrogen administration, similarly induces a reduction in waist-to-hip ratio and redistribution mimicking female patterns, underscoring estrogen's causal influence.[14] Genetic factors substantially determine variation in female body shape, with twin studies estimating heritability of waist-hip ratio (WHR) at 40-60% after accounting for age and behavioral confounders.[15] [16] Complex segregation analyses and genome-wide association studies reveal polygenic control over fat distribution, including sex-specific loci influencing subcutaneous versus visceral fat partitioning.[17] [18] These genetic influences interact with hormones; for instance, variants associated with estrogen receptor activity can modulate pelvic breadth and hip fat localization, contributing to inter-individual differences in shape independent of overall adiposity.[19] Environmental factors explain the remainder of variance, but genetic effects predominate in longitudinal stability of traits like WHR across the lifespan.[20]Fat Distribution Patterns

Females characteristically display a gynoid fat distribution pattern, with adipose tissue preferentially accumulating in the gluteofemoral region—including the hips, thighs, and buttocks—resulting in a lower waist-to-hip ratio compared to males.[21] This contrasts with the android pattern predominant in males, where fat deposits more centrally around the abdomen and viscera.[22] On average, females maintain 6–11% higher total body fat percentage than males, with a greater proportion stored subcutaneously rather than viscerally.[21] Estrogen plays a primary causal role in directing this lower-body deposition by enhancing subcutaneous fat storage and inhibiting lipolysis in femoral and gluteal depots via upregulation of α2A-adrenergic receptors, which suppress fat breakdown.[23] [24] In premenopausal females, elevated estrogen levels correlate with reduced abdominal fat accumulation, fostering the characteristic pear-shaped silhouette.[14] Androgens, conversely, promote visceral fat in both sexes, but their lower levels in females limit this effect until menopause, when estrogen decline triggers a redistribution toward android patterns, increasing intra-abdominal fat by up to 50% in some cohorts. [25] Population-level variations exist, influenced by genetics and ethnicity; for instance, non-Hispanic Black females exhibit higher overall adiposity and more pronounced gynoid distribution than non-Hispanic White females, with obesity prevalence reaching 57% versus 40% in the latter group as of recent U.S. data.[26] Asian females tend toward lower total fat but similar gynoid preferences, while genetic factors accounting for 30–70% of variance in distribution underscore heritability over environmental influences alone.[27] [1] These patterns persist across cultures, with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry studies confirming sex-specific regional differences independent of total fat mass.[28]Skeletal and Muscular Dimorphism

Human females exhibit distinct skeletal dimorphism compared to males, characterized primarily by adaptations for reproduction and locomotion. The female pelvis is wider and shallower, with a larger pelvic inlet and outlet to facilitate childbirth, resulting in greater inter-acetabular distance and a more oval-shaped birth canal. [29] [30] This configuration increases the bi-iliac breadth relative to body size, contributing to the broader hip structure that underlies female body shapes such as the pear or hourglass forms. [31] In contrast, males possess a narrower, more robust pelvis with a heart-shaped inlet optimized for weight-bearing efficiency in bipedalism. [32] Shoulder morphology also displays sexual dimorphism, with females having narrower clavicles and scapulae, leading to reduced biacromial breadth. [33] [34] Males, conversely, exhibit broader shoulders due to larger scapular size and greater upper body skeletal robusticity, even when scaled for height. [29] These differences establish the skeletal framework for body shape ratios; in females, the combination of narrower shoulders and wider hips typically yields a shoulder-to-hip ratio below 1.0, accentuating waist definition when combined with fat distribution. [35] Overall, female long bones are shorter and less robust relative to body mass, with lower cortical thickness, reflecting lower mechanical loading demands. [36] [37] Muscular dimorphism further differentiates female body shape, with males possessing substantially greater total skeletal muscle mass—approximately 36-65% more than females across populations. [38] [39] This disparity is most pronounced in the upper body, where males have 75-78% more arm muscle mass, compared to 41-50% more in the legs, resulting in less muscular bulk and a smoother contour in females. [39] Females exhibit a higher proportion of type I (slow-twitch) fibers and favor lipid oxidation over glycolysis in muscle metabolism, which supports endurance but limits hypertrophy. [40] [41] Consequently, female musculature contributes minimally to visible shape alterations, allowing adipose tissue to dominate curves, whereas male muscle accentuates angularity and V-shaped torsos. [42] These traits emerge post-puberty under androgen influence, with females showing earlier but less extensive gains in muscle and bone. [43]Developmental and Lifecycle Changes

During puberty, typically beginning between ages 8 and 13, estrogen surge promotes breast development (thelarche), pubic hair growth (pubarche), and a growth spurt, with fat redistributing to the hips, thighs, and breasts, increasing overall body fat percentage from about 15-20% prepubertally to 25-30% by late adolescence.[44][45] This results in a shift toward gynoid fat patterning, with hips widening by 5-10 cm on average due to pelvic bone growth and soft tissue deposition, lowering the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) to its reproductive optimum of approximately 0.7 in early adulthood.[46] Fat-free mass peaks around menarche and stabilizes, contrasting with continued lean mass gains in males.[45] In reproductive years, body shape remains relatively stable absent major events like pregnancy, though parity influences fat distribution; multiparous women exhibit slightly higher central fat accumulation over time compared to nulliparous peers.[6] Pregnancy induces temporary expansions in abdominal girth, breast size, and lower-body fat reserves (e.g., thighs and buttocks) to support fetal energy needs, with average maternal fat gain of 2-4 kg beyond fetal/placental weight, often mobilizing preferentially from gluteofemoral depots postpartum via lactation.[47][48] Permanent changes may include pelvic widening by 1-2 cm per pregnancy due to relaxin-mediated ligament laxity, potentially altering WHR minimally but increasing hip circumference. Perimenopause and menopause, starting around age 45-55, coincide with estrogen decline, driving a redistribution from peripheral (gynoid) to central (android) fat: postmenopausal women accrue 36% more trunk fat, 49% greater intra-abdominal fat area, and 22% more subcutaneous abdominal fat versus premenopausal counterparts, elevating WHR toward male-typical levels (e.g., from 0.75 to 0.85).[49][50] This shift accelerates annual fat mass gain by 2-3 fold during the menopausal transition, independent of total weight changes, and heightens visceral adiposity risks.[51] Hormone therapy may attenuate but not fully prevent these patterns.[52] Post-menopause, aging compounds these effects through sarcopenia and reduced metabolic rate, with women gaining 0.5-1 kg annually in central fat while lean mass declines 1-2% per decade after age 50, further increasing WHR and waist circumference by 5-10 cm over 20 years.[53][54] Empirical longitudinal data confirm age-driven WHR rises persist beyond menopause, driven by both hormonal and lifestyle factors, though baseline parity and genetics modulate variance.[46][6]Evolutionary and Adaptive Perspectives

Waist-Hip Ratio as Reproductive Indicator

The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), defined as the circumference of the waist divided by the circumference of the hips, reflects gynoid fat distribution patterns in women, where lower ratios indicate fat preferentially stored in the hips and thighs rather than the abdomen. Empirical research links a WHR of approximately 0.7 to enhanced reproductive indicators, including higher estrogen levels relative to androgens, which support ovulation and fecundity. Complementing WHR, body fat percentages of 21-32% support regular ovulation and fertility, with levels below approximately 17-22% disrupting menstrual cycles; BMI values of 18.5-24.9 kg/m² are associated with optimal fertility, lower miscarriage risk, and fewer childbirth complications compared to underweight or obesity; while no specific ideal height exists, shorter stature may slightly increase risks of difficult labor in some populations, though modern medical care mitigates this. [55] This ratio correlates with youthfulness and reproductive endocrinologic status, as women with lower WHR exhibit biomarkers of better ovarian reserve and lower risks of hormone-dependent disorders that impair fertility. [56] Cross-cultural studies demonstrate a consistent preference for female figures with WHR around 0.7, interpreted as an evolved cue signaling reproductive viability rather than cultural artifact, with neural imaging showing activation of reward centers in male observers viewing such silhouettes. [57] [58] Physiologically, elevated WHR (>0.8) predicts reduced fertility outcomes, including lower live birth rates in assisted reproduction cycles, independent of body mass index in some cohorts. [59] A 2024 analysis of over 2,000 women found higher WHR positively associated with infertility risk, attributing this to abdominal adiposity's disruption of metabolic and hormonal pathways essential for conception. [60] Longitudinal data further substantiate WHR's role, with women maintaining lower ratios showing decreased miscarriage rates and improved fetal development prospects, likely due to optimal pelvic resource allocation during gestation. [4] While not infallible—factors like overall adiposity modulate effects—WHR outperforms BMI in prognosticating reproductive health, as android fat patterns (higher WHR) correlate with insulin resistance and ovulatory dysfunction in conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome. [61] These associations hold across populations, underscoring WHR as a reliable, if proximate, biomarker of evolutionary fitness tied to reproductive success. [62]Sexual Selection and Attractiveness Cues

Sexual selection has shaped human mate preferences, with male attraction to specific female body shapes serving as cues to reproductive viability and health. Empirical studies demonstrate that men preferentially rate female figures exhibiting a low waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) of approximately 0.70 as most attractive, a pattern observed using line-drawn silhouettes independent of overall body weight.[63] This preference correlates with indicators of youthfulness, estrogenic fat distribution, and reproductive endocrinology status, suggesting an evolved mechanism to detect potential fertility.[63] [64] Cross-cultural investigations reinforce the robustness of low WHR as an attractiveness cue, with consistency reported among populations including Western undergraduates, Hadza foragers in Tanzania, and others, despite variations in preferred absolute body size influenced by local ecology.[64] Low WHR signals lower parity, reduced risk of gynecological disorders, and higher fecundity in premenopausal women, aligning with sexual selection for mates offering high reproductive returns.[64] However, correlations between WHR and fertility weaken in young, non-obese cohorts, indicating that attractiveness judgments may prioritize honest signals of genetic quality or developmental stability over direct fecundity metrics.[64] Beyond WHR, recent analyses highlight curviness—quantified as the mean absolute curvature of the torso—as a superior predictor of female body attractiveness, accounting for 92% of variance in male ratings across varying body widths, compared to 63% for fixed WHR thresholds.[65] Optimal curviness (intermediate level) evokes hourglass silhouettes, emphasizing hip and bust prominence relative to waist, which may better capture multidimensional cues to estrogen-mediated fat deposition and biomechanical efficiency for childbearing.[65] These shape preferences persist in short-term mating contexts, underscoring their role in immediate assessments of mate value under sexual selection pressures.[64]Empirical Evidence from Cross-Cultural Studies

Cross-cultural studies consistently demonstrate a preference for female body shapes characterized by a low waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) of approximately 0.7, indicating an hourglass figure, across diverse populations including Western and non-Western groups. In a study involving participants from the United States, Greece, and other regions, raters selected figures with a 0.7 WHR as most attractive irrespective of body mass index (BMI) variations, suggesting this ratio serves as a robust cue beyond overall size.[57] Similarly, research across Iran, Norway, Poland, and Russia found men preferring WHR values around 0.7 to 0.8 in women, with relative consistency despite national differences in average body sizes.[65] These findings align with evolutionary hypotheses linking low WHR to indicators of fertility and health, as lower ratios correlate with better reproductive outcomes in empirical data from multiple ethnic groups.[66] Further evidence from indigenous and subsistence-level societies reinforces this pattern. Among the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania and Matsiguenka of Peru, male participants rated silhouettes with a 0.7 WHR highest in attractiveness, even when presented without cultural priming, outperforming higher or lower ratios.[62] A comparative analysis in three European countries (Austria, UK, Sweden) and extending to non-European samples confirmed that while preferred BMI varied with local norms—higher in food-scarce contexts—WHR preferences remained anchored near 0.7, independent of socioeconomic factors.[67] This dissociation between size and shape preferences highlights WHR's potential universality, as preferences for ratios below population averages persisted across 12 cultures in a meta-analysis of attractiveness ratings.[66] Variations exist, particularly in absolute WHR values influenced by androgen levels or ecology, with non-Western women often exhibiting higher natural WHRs (0.8–0.9) yet still favoring lower ratios in mate selection tasks.[68] For instance, British and Greek subjects both peaked at 0.7 WHR but diverged slightly on weight ideals, underscoring shape's primacy over mass in cross-cultural judgments.[69] Recent work using 3D models further validates curviness—tied to WHR—as a stronger predictor of attractiveness than WHR alone in multi-ethnic samples, though the optimal curviness aligns with 0.7 ratios evolutionarily.[65] These patterns, drawn from controlled experiments with standardized stimuli, counter claims of pure cultural relativism by evidencing convergent selection pressures.[64]Anthropometric Classification and Variations

Standard Body Shape Categories

Standard body shape categories for females are derived from anthropometric measurements, primarily the relative proportions of bust, waist, and hip circumferences, which reflect skeletal structure, fat distribution, and muscular development. These classifications, while useful for apparel design, health assessments, and ergonomic studies, are approximations rather than rigid biological taxa, as individual variations in measurement precision can reassign up to 40% of women across categories when tape placement shifts by as little as 1 cm. Common schemes identify five primary shapes—rectangle, inverted triangle, pear (or spoon), hourglass, and apple (or oval)—based on deviations from average ratios where bust approximates hips and waist is 75-85% of those values.[70][71][72] The rectangle (also termed banana or straight) features minimal waist definition, with bust, waist, and hip measurements differing by less than 5 cm, resulting in a linear silhouette often associated with athletic or ectomorphic builds and lower overall body fat. This shape predominates in populations with higher lean mass relative to adipose tissue.[70][72][73] In contrast, the inverted triangle exhibits broader shoulders and bust relative to hips, where bust exceeds hips by 5-10 cm or more, with a waist similar to or slightly narrower than hips; this configuration correlates with upper-body muscularity or androgen-influenced fat patterns, though less common in females due to typical gynoid fat storage.[70][72][73] The pear (or spoon/triangle) shape involves hips wider than bust by at least 5 cm, paired with a defined waist (typically 25% narrower than hips), emphasizing lower-body fat accumulation driven by estrogen-mediated patterns; a 170 cm woman with a pronounced curvy pear shape featuring very large wide hips, big butt, and thick thighs typically weighs 65-85 kg (BMI 22-29), higher than the general healthy range of 54-73 kg (BMI 18.5-24.9) due to increased lower body mass distribution, while often remaining healthy for many individuals. In shorter women, such as those at 4'10" (148 cm) and 150 lbs (68 kg; BMI ≈31, in the obese range), the pear shape manifests as narrow shoulders, a smaller bust, defined waist, and markedly wider hips with fuller thighs and buttocks, creating a compact, bottom-heavy silhouette with curvaceous lower body contours; while obesity may introduce softer overall features including some abdominal fullness, the primary fat accumulation remains gynoid in the lower half. This category is prevalent in many ethnic groups, comprising up to 20-30% of classifications in anthropometric surveys.[70][72][74] Hourglass proportions balance bust and hips within 2-5 cm of each other, with waist at least 25% smaller (e.g., waist-to-hip ratio around 0.7), yielding a curvilinear form linked to optimal reproductive signaling in evolutionary models, though rare in general populations (estimated at 8-10% of women).[70][72][73] Finally, the apple (or oval/round) displays a fuller waist exceeding bust or hips by more than 5 cm, indicative of central (android) fat deposition, which anthropometric data associates with metabolic risks independent of total body mass; this shape increases with age and postmenopausal hormonal shifts.[70][72][74] Alternative schemes from 3D scanning and torso-focused anthropometry propose four categories—oval, circle, triangle, rectangle—prioritizing sagittal contours over frontal ratios for applications like garment prototyping, but these overlap substantially with the above and yield similar prevalence distributions in large datasets (e.g., n>5,000 scans). Peer-reviewed classifications emphasize that no system captures all variance, as genetic, ethnic, and lifestyle factors yield continuous rather than discrete distributions.[75][74]Key Measurement Ratios and Standards

The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), defined as the circumference of the waist measured at the narrowest point divided by the circumference of the hips at their widest point, serves as the primary anthropometric ratio for assessing female body shape, particularly lower body fat distribution and curviness.[2] Health organizations establish standards where a WHR exceeding 0.85 in women indicates increased abdominal adiposity and associated risks for cardiovascular disease and metabolic disorders.[76] Empirical data from peer-reviewed studies report average WHR values of approximately 0.72 in young European women and 0.79 in nulliparous women from traditional societies, with values typically rising to 0.88 or higher after multiple pregnancies due to factors like age and parity.[2][46] Lower WHRs (0.65–0.75) correlate with enhanced reproductive health markers, including higher estradiol levels and lower incidence of conditions like diabetes.[2] Complementary ratios include the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), calculated as waist circumference divided by height, with a standard threshold below 0.5 deemed optimal for minimizing cardiometabolic risks in women across populations.[54] For upper-lower body proportionality, shoulder-to-hip ratios contribute to classifications, though WHR remains dominant for shape delineation. In apparel and anthropometric contexts, body shapes are categorized using relative bust-waist-hip (BWH) measurements, where bust and hip circumferences are taken at their maxima and waist at the natural minimum.| Body Shape Category | Key Ratio Criteria |

|---|---|

| Hourglass | Bust and hips within 5% of each other; waist at least 25% smaller than both, yielding WHR ≈0.7.[73][2] |

| Pear (Gynoid) | Hips exceed bust by >2 inches (5 cm); waist defined but narrower than hips, often WHR <0.8.[72] |

| Rectangle (Athletic) | Bust ≈ waist ≈ hips (differences <2 inches or 5 cm); minimal waist indentation, WHR ≈0.8–0.85.[72] |

| Inverted Triangle | Shoulders/bust exceed hips by >3 inches (7.6 cm); narrower hips, higher effective WHR.[72] |

| Apple (Android) | Waist exceeds hips or bust; WHR >0.85, indicating central fat accumulation.[72][76] |

Population-Level Differences

Population-level differences in female body shape primarily manifest in variations of fat distribution patterns, waist-to-hip ratios (WHR), and android-to-gynoid fat ratios, influenced by genetic and evolutionary factors independent of overall obesity levels. African-descent women tend to exhibit lower average WHR and greater deposition of subcutaneous fat in gluteofemoral regions, resulting in more pronounced pear-shaped morphologies and greater gluteal prominence compared to European-descent women, who typically exhibit middle-range global proportions, often pear-shaped but not extreme.[79] [80] [81] Prominent or large buttocks are more associated with certain African, Hispanic/Latin American, or Indigenous ancestries, linked to lower WHR and enhanced gluteal fat storage and projection. For instance, studies using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans show African American women having smaller WHR values alongside larger absolute waist and hip circumferences relative to Caucasians, reflecting enhanced peripheral fat storage. [79] In contrast, East Asian women demonstrate higher android/gynoid fat ratios, indicating relatively more visceral and abdominal fat accumulation even at lower body mass indices (BMI), which contributes to less gynoid emphasis in body shape. [82] [83] Pubertal girls of Asian descent exhibit android/gynoid ratios approximately 16% higher than white counterparts (0.369 versus 0.318 after adjustments for puberty stage and BMI), predisposing to more centralized fat patterns. [83] Hispanic women show similar elevations in android/gynoid ratios to Asians (0.364), correlating with increased central adiposity risks distinct from overall body fat percentage. [83] [84] Southern European women often present higher average BMI, waist circumference, and WHR than Northern Europeans or Asians, linking to greater overall anthropometric obesity measures across populations. [85] These patterns persist after controlling for age and parity, with genetic analyses revealing ethnicity-specific loci regulating fat depot preferences, such as reduced central fat in Africans relative to Asians. [82] Skeletal dimorphisms, including pelvic width variations, further modulate shape; for example, broader bi-iliac diameters in African women enhance hip prominence, amplifying gynoid traits beyond soft tissue alone. [26] Such differences underscore causal roles of ancestry in body composition, with implications for metabolic profiles independent of cultural or environmental confounders. [86]Health and Physiological Risks

Android vs. Gynoid Fat Distribution Effects

Android fat distribution, involving preferential accumulation in the abdominal and visceral regions, is strongly associated with adverse metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes in women. Visceral adipose tissue in this pattern releases free fatty acids directly into the portal vein, promoting hepatic insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and inflammation, which elevate risks for type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. A 2023 study of over 10,000 participants found that higher android fat mass independently predicted insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, even after adjusting for body mass index (BMI), with women showing pronounced effects due to hormonal shifts like post-menopause estrogen decline.[87] [88] Similarly, android-dominant obesity correlates with a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events, driven by endothelial dysfunction and atherogenic lipid profiles.[89] In gynoid fat distribution, subcutaneous fat accumulates primarily in the gluteofemoral areas (hips and thighs), which is metabolically protective relative to android patterns. This depot exhibits greater insulin sensitivity and lipolytic resistance, contributing to lower circulating triglycerides and higher adiponectin levels that mitigate inflammation and improve glucose homeostasis. Research from 2023 demonstrated that BMI-adjusted increases in gluteofemoral fat were linked to reduced low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiometabolic risk scores in women, contrasting with visceral fat's detrimental effects.[90] [91] However, while gynoid fat confers relative benefits, excessive overall adiposity in this pattern still heightens all-cause mortality risks, particularly in older women where ratios of android-to-gynoid fat exceeding 0.9 signal elevated hypertension and reduced HDL cholesterol.[92] [93] Comparative analyses underscore the android-to-gynoid ratio (A/G) as a superior predictor of health risks over BMI alone. Women with A/G ratios above 1.0 face up to 40% higher odds of cardiovascular disease progression, including aortic calcification, due to android fat's promotion of arterial stiffness, whereas gynoid-dominant distributions (A/G < 0.8) show inverse associations with these markers. A 2024 dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)-based study confirmed that android fat drives metabolically unhealthy lean phenotypes in women, while gynoid deficits characterize metabolically unhealthy obesity, highlighting distribution's causal role beyond total fat mass. Interventions targeting android reduction, such as exercise-induced visceral fat loss, yield greater cardiometabolic improvements than equivalent gynoid losses.[94] [95] [96]| Health Outcome | Android Fat Effect | Gynoid Fat Effect | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Resistance | Increased (OR 1.5–2.0) | Decreased or neutral | Adjusted for BMI in large cohorts[87] |

| Cardiovascular Risk | Elevated (e.g., higher BP, lower HDL) | Protective (e.g., reduced calcification) | DXA ratio studies in women[92] [95] |

| Dyslipidemia | Pro-atherogenic (↑ triglycerides) | Favorable (↓ LDL, ↑ adiponectin) | Depot-specific associations[91] [97] |

| Mortality Risk | Higher with elevated A/G ratio | Lower with gynoid dominance | Older women longitudinal data[93] |