Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Hip | |

|---|---|

Bones of the hip region | |

Right hip of a female human | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | coxa |

| Greek | ισχίο |

| MeSH | D006615 |

| TA98 | A01.2.08.005 A01.1.00.034 |

| TA2 | 316, 158 |

| FMA | 24964 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In vertebrate anatomy, the hip, or coxa[1] (pl.: coxae) in medical terminology, refers to either an anatomical region or a joint on the outer (lateral) side of the pelvis.

The hip region is located lateral and anterior to the gluteal region, inferior to the iliac crest, and lateral to the obturator foramen, with muscle tendons and soft tissues overlying the greater trochanter of the femur.[2] In adults, the three pelvic bones (ilium, ischium and pubis) have fused into one hip bone, which forms the superomedial/deep wall of the hip region.

The hip joint, scientifically referred to as the acetabulofemoral joint (art. coxae), is the ball-and-socket joint between the pelvic acetabulum and the femoral head. Its primary function is to support the weight of the torso in both static (e.g. standing) and dynamic (e.g. walking or running) postures. The hip joints have very important roles in retaining balance, and for maintaining the pelvic inclination angle.

Pain of the hip may be the result of numerous causes, including nervous, osteoarthritic, infectious, traumatic, and genetic.

Structure

[edit]Region

[edit]The hip joint, also known as a ball and socket joint, is formed by the acetabulum of the pelvis and the femoral head, which is the top portion of the thigh bone (femur). It allows for a wide range of movement and stability in the lower body.[3]

The proximal femur is largely covered by muscles and, as a consequence, the greater trochanter is often the only palpable bony structure in the hip region.[4]

Articulation

[edit]

The hip joint or coxofemoral joint[5][6] is a ball and socket synovial joint formed by the articulation of the rounded head of the femur and the cup-like acetabulum of the pelvis.[7] The socket of the acetabulum is pointing downwards and anterolaterally. The socket is also turned such that the outer edge of its roof is more lateral than outer edge of the floor.[7] It forms the primary connection between the bones of the lower limb and the axial skeleton of the trunk and pelvis. Both joint surfaces are covered with a strong but lubricated layer called articular hyaline cartilage.

The cuplike acetabulum forms at the union of three pelvic bones — the ilium, pubis, and ischium.[8] The Y-shaped growth plate that separates them, the triradiate cartilage, is fused definitively at ages 14–16.[9] It is a special type of spheroidal or ball and socket joint where the roughly spherical femoral head is largely contained within the acetabulum and has an average radius of curvature of 2.5 cm.[10] The acetabulum grasps almost half the femoral ball, a grip deepened by a ring-shaped fibrocartilaginous lip, the acetabular labrum, which extends the joint beyond the equator.[8] The centre of the acetabulum (fovea) does not articulate to anything. Instead, it is lined with fat pad and attached to ligamentum teres. The acetabular labrum is horse-shoe shaped. Its inferior notch is bridged by transverse acetabular ligament.[7] The joint space between the femoral head and the superior acetabulum is normally between 2 and 7 mm.[11]

The head of the femur is attached to the shaft by a thin neck region that is often prone to fracture in the elderly, which is mainly due to the degenerative effects of osteoporosis.

The acetabulum is oriented inferiorly, laterally and anteriorly, while the femoral neck is directed superiorly, medially, and slightly anteriorly.

Articular angles

[edit]Acetabular angle (or Sharp's angle)[12] is the angle between the horizontal line passing through the inferior aspects of triradiate cartilages (Hilgenreiner's line) and another line passing through the inferior angle of triradiate cartilage to superior acetabular rim. The angle measures 35 degrees at birth, 25 degrees at one year of age, and less than 10 degrees by 15 years of age.[13] In adults the angle can vary from 33 to 38 degrees.[14]

The sagittal angle of the acetabular inlet is an angle between a line passing from the anterior to the posterior acetabular rim and the sagittal plane. It measures 7° at birth and increases to 17° in adults.[13]

Wiberg's centre-edge angle (CE angle) is an angle between a vertical line and a line from the centre of the femoral head to the most lateral part of the acetabulum,[15] as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph.[16]

The vertical-centre-anterior margin angle (VCA) is an angle formed from a vertical line (V) and a line from the centre of the femoral head (C) and the anterior (A) edge of the dense shadow of the subchondral bone slightly posterior to the anterior edge of the acetabulum, with the radiograph being taken from the false angle, that is, a lateral view rotated 25 degrees towards becoming frontal.[16]

The articular cartilage angle (AC angle, also called acetabular index[17] or Hilgenreiner angle) is an angle formed parallel to the weight bearing dome, that is, the acetabular sourcil or "roof",[18] and the horizontal plane,[15] or a line connecting the corner of the triangular cartilage and the lateral acetabular rim.[19] In normal hips in children aged between 11 and 24 months, it has been estimated to be on average 20°, ranging between 18° and 25°.[20] It becomes progressively lower with age.[21] Suggested cutoff values to classify the angle as abnormally increased include:

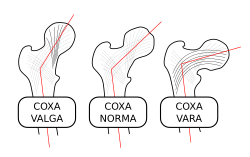

Femoral neck angle

[edit]The angle between the longitudinal axes of the femoral neck and shaft, called the caput-collum-diaphyseal angle or CCD angle, normally measures approximately 150° in newborn and 126° in adults (coxa norma).[23][dubious – discuss]

An abnormally small angle is known as coxa vara and an abnormally large angle as coxa valga. Because changes in shape of the femur naturally affects the knee, coxa valga is often combined with genu varum (bow-leggedness), while coxa vara leads to genu valgum (knock-knees).[24]

Changes in the CCD angle is the result of changes in the stress patterns applied to the hip joint. Such changes, caused for example by a dislocation, change the trabecular patterns inside the bones. Two continuous trabecular systems emerging on the auricular surface of the sacroiliac joint meander and criss-cross each other down through the hip bone, the femoral head, neck, and shaft.

- In the hip bone, one system arises on the upper part of the auricular surface to converge onto the posterior surface of the greater sciatic notch, from where its trabeculae are reflected to the inferior part of the acetabulum. The other system emerges on the lower part of the auricular surface, converges at the level of the superior gluteal line, and is reflected laterally onto the upper part of the acetabulum.

- In the femur, the first system lines up with a system arising from the lateral part of the femoral shaft to stretch to the inferior portion of the femoral neck and head. The other system lines up with a system in the femur stretching from the medial part of the femoral shaft to the superior part of the femoral head.[25]

On the lateral side of the hip joint the fascia lata is strengthened to form the iliotibial tract which functions as a tension band and reduces the bending loads on the proximal part of the femur.[23]

Capsule

[edit]Proximally, capsule of the hip joint is attached to the edge of the acetabulum, acetabular labrum, and transverse acetabular ligament. Distally, it is attached to the trochanters of the femur and intertrochanteric line anteriorly. Posteriorly, it is attached to a junction between medial two-thirds and lateral one-third of the femoral neck,[7] one finger breadth away from the intertrochanteric crest.[24] From its attachment at the femoral neck, the fibres of the capsule reflected backwards towards the acetabulum, carrying retinacula vessels supplying the femoral head.[7] The part of femoral neck outside the capsule is shorter in front than posteriorly.[24]

The strong but loose fibrous capsule of the hip joint permits the hip joint to have the second largest range of movement (second only to the shoulder) and yet support the weight of the body, arms and head.

The capsule has two sets of fibers: longitudinal and circular.

- The circular fibers form a collar around the femoral neck called the zona orbicularis.

- The longitudinal retinacular fibers travel along the neck and carry blood vessels.

Ligaments

[edit]The hip joint is reinforced by four ligaments, of which three are extracapsular and one intracapsular.

The extracapsular ligaments are the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments attached to the bones of the pelvis (the ilium, ischium, and pubis respectively). All three strengthen the capsule and prevent an excessive range of movement in the joint. Of these, the Y-shaped and twisted iliofemoral ligament is the strongest ligament in the human body. It has a tensile strength of 350 kg.[24] Iliofemoral ligament is a thickening of the anterior capsule extending from anterior inferior iliac spine to intertrochanteric line.[7] Ischiofemoral ligament is the thickening of posterior capsule of the hip and pubofemoral ligament is the thickening of the inferior capsule.[7] In the upright position, iliofemoral ligament prevents the trunk from falling backward without the need for muscular activity, thus preventing excessive hyperextension. In the sitting position, it becomes relaxed, thus permitting the pelvis to tilt backward into its sitting position. Ischiofemoral prevents excessive extension and the pubofemoral ligament prevents excess abduction and extension.[26]

The zona orbicularis, which lies like a collar around the most narrow part of the femoral neck, is covered by the other ligaments which partly radiate into it. The zona orbicularis acts like a buttonhole on the femoral head and assists in maintaining the contact in the joint.[24] All three ligaments become taut when the joint is extended - this stabilises the joint, and reduces the energy demand of muscles when standing.[27]

The intracapsular ligament, the ligamentum teres, is attached to a depression in the acetabulum (the acetabular notch) and a depression on the femoral head (the fovea of the head). It is only stretched when the hip is dislocated, and may then prevent further displacement.[24] It is not that important as a ligament but can often be vitally important as a conduit of a small artery to the head of the femur, that is, the foveal artery.[28] This artery is not present in everyone but can become the only blood supply to the bone in the head of the femur when the neck of the femur is fractured or disrupted by injury in childhood.[29]

Blood supply

[edit]The hip joint is supplied with blood from the medial circumflex femoral and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, which are both usually branches of the deep artery of the thigh (profunda femoris), but there are numerous variations and one or both may also arise directly from the femoral artery. There is also a small contribution from the foveal artery, a small vessel in the ligament of the head of the femur which is a branch of the posterior division of the obturator artery, which becomes important to avoid avascular necrosis of the head of the femur when the blood supply from the medial and lateral circumflex arteries are disrupted (e.g. through fracture of the neck of the femur along their course).[29]

The hip has two anatomically important anastomoses, the cruciate and the trochanteric anastomoses, the latter of which provides most of the blood to the head of the femur. These anastomoses exist between the femoral artery or profunda femoris and the gluteal vessels.[30]

Muscles and movements

[edit]The hip muscles act on three mutually perpendicular main axes, all of which pass through the center of the femoral head, resulting in three degrees of freedom and three pair of principal directions: Flexion and extension around a transverse axis (left-right); lateral rotation and medial rotation around a longitudinal axis (along the thigh); and abduction and adduction around a sagittal axis (forward-backward);[31] and a combination of these movements (i.e. circumduction, a compound movement in which the leg describes the surface of an irregular cone).[24] Some of the hip muscles also act on either the vertebral joints or the knee joint, that with their extensive areas of origin and/or insertion, different part of individual muscles participate in very different movements, and that the range of movement varies with the position of the hip joint.[24] Additionally, the inferior and Superior gemelli muscles assist the obturator internus and the three muscles together form the three-headed muscle known as the triceps coxae.[32][24]

The movements of the hip joint is thus performed by a series of muscles which are here presented in order of importance[24] with the range of motion from the neutral zero-degree position[31] indicated:

- Lateral or external rotation (30° with the hip extended, 50° with the hip flexed): gluteus maximus; quadratus femoris; obturator internus; dorsal fibers of gluteus medius and minimus; iliopsoas (including psoas major from the vertebral column); obturator externus; adductor magnus, longus, brevis, and minimus; piriformis; and sartorius. The iliofemoral ligament inhibits lateral rotation and extension, this is why the hip can rotate laterally to a greater degree when it is flexed.

- Medial or internal rotation (40°): anterior fibers of gluteus medius and minimus; tensor fasciae latae; the part of adductor magnus inserted into the adductor tubercle; and, with the leg abducted also the pectineus.

- Extension or retroversion (20°): gluteus maximus (if put out of action, active standing from a sitting position is not possible, but standing and walking on a flat surface is); dorsal fibers of gluteus medius and minimus; adductor magnus; and piriformis. Additionally, the following thigh muscles extend the hip: semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and long head of biceps femoris. Maximal extension is inhibited by the iliofemoral ligament.

- Flexion or anteversion (140°): the hip flexors: iliopsoas (with psoas major from vertebral column); tensor fasciae latae, pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, and gracilis. Thigh muscles acting as hip flexors: rectus femoris and sartorius. Maximal flexion is inhibited by the thigh coming in contact with the chest.

- Abduction (50° with hip extended, 80° with hip flexed): gluteus medius; tensor fasciae latae; gluteus maximus with its attachment at the fascia lata; gluteus minimus; piriformis; and obturator internus. Maximal abduction is inhibited by the neck of the femur coming into contact with the lateral pelvis. When the hips are flexed, this delays the impingement until a greater angle.

- Adduction (30° with hip extended, 20° with hip flexed): adductor magnus with adductor minimus; adductor longus, adductor brevis, gluteus maximus with its attachment at the gluteal tuberosity; gracilis (extends to the tibia); pectineus, quadratus femoris; and obturator externus. Of the thigh muscles, semitendinosus is especially involved in hip adduction. Maximal adduction is impeded by the thighs coming into contact with one another. This can be avoided by abducting the opposite leg, or having the legs alternately flexed/extended at the hip so they travel in different planes and do not intersect.

Clinical significance

[edit]A hip fracture is a break that occurs in the upper part of the femur.[33] Symptoms may include pain around the hip particularly with movement and shortening of the leg.[33] The hip joint can be replaced by a prosthesis in a hip replacement operation due to fractures or illnesses such as osteoarthritis. Hip pain can have multiple sources and can also be associated with lower back pain.

At the 2022 Consumer Electronics Show, a company named Safeware announced an airbag belt that is designed to prevent hip fractures among such uses as the elderly and hospital patients.[34]

Abnormal orientation of the acetabular socket as seen in hip dysplasia can lead to hip subluxation (partial dislocation), degeneration of the acetabular labrum. Excessive coverage of femoral head by the acetabulum can lead to pincer-type femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI).[7]

Sexual dimorphism and cultural significance

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2025) |

In humans, unlike other animals, the hip bones are substantially different in the two sexes. The hips of human females widen during puberty.[35] The femora are also more widely spaced in females, so as to widen the opening in the hip bone and thus facilitate childbirth. Finally, the ilium and its muscle attachment are shaped so as to situate the buttocks away from the birth canal, where contraction of the buttocks could otherwise damage the baby.

The female hips have long been associated with both fertility and general expression of sexuality. Since broad hips facilitate childbirth and also serve as an anatomical cue of sexual maturity, they have been seen as an attractive trait for women for thousands of years. Many of the classical poses women take when sculpted, painted or photographed, such as the Grande Odalisque, serve to emphasize the prominence of their hips. Similarly, women's fashion through the ages has often drawn attention to the girth of the wearer's hips.

Additional images

[edit]-

Hip joint. Lateral view.

-

Hip joint. Lateral view.

-

Muscles of Thigh. Anterior views.

-

Illustration of Hip (Frontal view).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Latin coxa was used by Celsus in the sense "hip", but by Pliny the Elder in the sense "hip bone" (Diab, p 77)

- ^ "hip region". MediLexicon. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ Green, Shelby (15 December 2022). "Everything You Need to Know About Hip Anatomy". Feel Good Life. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 381

- ^ "Hip joint - e-Anatomy - IMAIOS".

- ^ "Understanding the Coxofemoral Joint: Anatomy, Functions, and Common Causes of Hip Pain". 31 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ryan, Stephanie (2011). "Chapter 8". Anatomy for diagnostic imaging (Third ed.). Elsevier Ltd. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-7020-2971-4.

- ^ a b Faller (2004), pp 174-175

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 365

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 378

- ^ Lequesne, M (2004). "The normal hip joint space: variations in width, shape, and architecture on 223 pelvic radiographs". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 63 (9): 1145–1151. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.018424. ISSN 0003-4967. PMC 1755132. PMID 15308525.

- ^ Saikia KC, Bhuyan SK, Rongphar R (July 2008). "Anthropometric study of the hip joint in northeastern region population with computed tomography scan". Indian J Orthop. 42 (3). Figure 2. doi:10.4103/0019-5413.39572 (inactive 10 July 2025). PMC 2739474. PMID 19753150.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ a b Schuenke, M; Schulte, E; Schumacher, U (2015). THIEME Atlas of Anatomy - Volume 1 - General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System (2nd ed.). China: Thieme Medical Pu blish ers, In c. p. 439. ISBN 978-1-60406-923-5.

- ^ Mannava S, Geeslin AG, Frangiamore SJ, Cinque ME, Geeslin MG, Chahla J, Philippon MJ (October 2017). "Comprehensive Clinical Evaluation of Femoroacetabular Impingement Part 2, Plain Radiography". Arthroscopy Techniques. 6 (5): e2003 – e2009. doi:10.1016/j.eats.2017.06.011. PMC 5794674. PMID 29399468.

- ^ a b Page 131 in: Whitehouse, Richard (2006). Imaging of the hip & bony pelvis: techniques and applications. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-20640-8.

- ^ a b [1] Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine Chosa, E.; Tajima, N. (2003). "Anterior acetabular head index of the hip on false-profile views. New index of anterior acetabular cover". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 85 (6): 826–829. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.85B6.14146. PMID 12931799.

- ^ Page 309 in: Jeffrey D. Placzek, David A. Boyce (2016). Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Secrets - E-Book (3 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-28683-1.

- ^ Setia, Rahul; Gaillard, Frank. "Developmental dysplasia of the hip". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- ^ Windhagen, H.; Thorey, F.; Kronewid, H.; Pressel, T.; Herold, D.; Stukenborg-Colsman, C. (2005). "The effect of functional splinting on mild dysplastic hips after walking onset". BMC Pediatrics. 5 (1). Figure 2. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-5-17. PMC 1166563. PMID 15958160.

- ^ Page 217 in: Frederic Shapiro (2002). Pediatric Orthopedic Deformities. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-053856-3.

- ^ Frank Gaillard. "Acetabular angle". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- ^ a b Page 942 in: Brian D. Coley (2013). Caffey's Pediatric Diagnostic Imaging (12 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-5360-4.

- ^ a b c Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 367

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. pp. 196, 198, 200, 244–246. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- ^ Palastanga (2006), p 353

- ^ Gold, M.; Munjal, A.; Varacallo, M. (2021). Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip Joint. StatPearls. PMID 29262200.

- ^ teachmeanatomy.net Archived 2013-01-03 at the Wayback Machine. teachmeanatomy.net. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ^ Hip Fracture in Emergency Medicine at Medscape. Author: Moira Davenport. Updated: Apr 2, 2012

- ^ a b Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pp 383, 440

- ^ Clemente (2006), p 227

- ^ a b Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 386

- ^ Moore, Keith L. (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia. p. 728. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Hip Fractures". OrthoInfo - AAOS. April 2009. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Patterson, Dan (2022-01-06). "Smart beds, disease detectors and other cool tech at CES". CBS News. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ^ "Reproductive Anatomy and Physiology". The Harriet and Robert Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ Ruiz Santiago, Fernando; Santiago Chinchilla, Alicia; Ansari, Afshin; Guzmán Álvarez, Luis; Castellano García, Maria del Mar; Martínez Martínez, Alberto; Tercedor Sánchez, Juan (2016). "Imaging of Hip Pain: From Radiography to Cross-Sectional Imaging Techniques". Radiology Research and Practice. 2016: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2016/6369237. ISSN 2090-1941. PMC 4738697. PMID 26885391. (Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

References

[edit]- Clemente, Carmine D. (2006). Clemente's Anatomy Dissector. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-6339-8.

- Diab, Mohammad (1999). Lexicon of Orthopaedic Etymology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 90-5702-597-3.

- Faller, Adolf; Schuenke, Michael; Schuenke, Gabriele (2004). The Human Body: An Introduction to Structure and Function. Thieme. ISBN 3-13-129271-7.

- Field, Derek (2001). Anatomy: palpation and surface markings (3rd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0-7506-4618-7.

- "Hip Region". MediLexicon. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- Palastanga, Nigel; Field, Derek; Soames, Roger (2006). Anatomy and human movement: structure and function (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0-7506-8814-9.

- Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. 2006. ISBN 978-1-58890-419-5.

External links

[edit]- Hip Preservation Awareness, information and support for hip impingement, hip dysplasia, and related issues in young adults (12-adult)

- Hip anatomy video

- High-performance hips

- Hip Pain ICD10

![X-ray of the hip, with measurements used in X-ray of hip dysplasia in adults.[36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Iliopectineal_line%2C_ilioischial_line%2C_tear_drop%2C_acetabular_fossa%2C_and_anterior_and_posterior_wall_of_the_acetabulumi.jpg/120px-Iliopectineal_line%2C_ilioischial_line%2C_tear_drop%2C_acetabular_fossa%2C_and_anterior_and_posterior_wall_of_the_acetabulumi.jpg)