Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

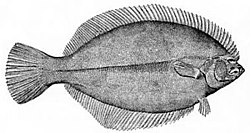

Flatfish

View on Wikipedia

| Flatfish Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Plaice (Pleuronectes platessa), the first named species of flatfish | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Carangiformes |

| Suborder: | Pleuronectoidei Cuvier, 1817[2] |

| Type species | |

| Pleuronectes platessa | |

| Families | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Flatfish are a group of ray-finned fish belonging to the suborder Pleuronectoidei and historically the order Pleuronectiformes (though this is now disputed). Their collective common name is due to their habit of lying on one side of their laterally-compressed body (flattened side-to-side) upon the seafloor; in this position, both eyes lie on the side of the head facing upwards, while the other side of the head and body (the "blind side") lies on the substrate. This loss of symmetry, a unique adaptation in vertebrates, stems from one eye "migrating" towards the other during the juvenile's metamorphosis; due to variation, some species tend to face their left side upward, some their right side, and others face either side upward.[example needed] They are one of the most speciose groups of demersal fish. Their cryptic coloration and habits, a form of camouflage, conceals them from potential predators.

Common names

[edit]

There are a multitude of common names for flatfish, as they are a widespread group of fish and important food fish across the world. The following are common flatfish names in English:

As these are merely common names, they do not conform with the "natural" relationships that are recovered through scientific studies of morphology or genetics. As examples, the three species consistently called "halibut" are themselves part of the right-eye flounder family, while the spiny turbots are not at all closely related to "true" turbot, but are consistently recovered in a "primitive" or basal position at the base of flatfish phylogenetic trees.

Distribution

[edit]Flatfishes are found in oceans worldwide, ranging from the Arctic, through the tropics, to Antarctica. Species diversity is centered in the Indo-West Pacific and declines following both latitudinal and longitudinal gradients away from this centre of diversity.[3] Most species are found in depths between 0 and 500 m (1,600 ft), but a few have been recorded from depths in excess of 1,500 m (4,900 ft). None have been confirmed from the abyssal or hadal zones of the deep sea; a reported observation of a flatfish from the Bathyscaphe Trieste's dive into the Mariana Trench (at a depth of almost 11 km (36,000 ft)) has been questioned by ichthyologists, and recent authorities do not recognize it as valid.[4] Among the deepwater species is Symphurus thermophilus, a tonguefish which congregates around "ponds" of sulphur at hydrothermal vents on the seafloor; no other flatfish is known from hydrothermal vent ecosystems.[5]

Conversely, many species will enter brackish or fresh water, and a smaller number of soles (families Achiridae and Soleidae) and tonguefish (Cynoglossidae) are entirely restricted to fresh water.[6][7][8]

Description

[edit]

The most obvious characteristic of the flatfish is their asymmetry, with both eyes lying on the same side of the head in the adult fish. In some families, the eyes are usually on the right side of the body (dextral or right-eyed flatfish), and in others, they are usually on the left (sinistral or left-eyed flatfish). The primitive spiny turbots include equal numbers of right- and left-sided individuals, and are generally less asymmetrical than the other families.[1] Other distinguishing features of the order are the presence of protrusible eyes, another adaptation to living on the seabed (benthos), and the extension of the dorsal fin onto the head.

The surface of the fish facing away from the sea floor is pigmented, often serving to camouflage the fish, but at times displaying striking patterns. Some flatfishes are also able to change their pigmentation to match the background using their chromatophores, in a manner similar to some cephalopods. The side of the body without the eyes, facing the seabed, is usually colourless or very pale.[1]

In general, flatfishes rely on their camouflage for avoiding predators, but some have aposematic traits such as conspicuous eyespots (e.g., Microchirus ocellatus) and several small tropical species (at least Aseraggodes, Pardachirus and Zebrias) are poisonous.[9][10][11] Juveniles of Soleichthys maculosus mimic toxic flatworms of the genus Pseudobiceros in both colours and swimming pattern.[12][13] Conversely, a few octopus species have been reported to mimic flatfishes in colours, shape and swimming mode.[14]

Flatfishes range in size from the sand flounder Tarphops oligolepis, measuring about 6.5 cm (2.6 in) in length,[15] and weighing 2 g (0.071 oz),[1] to the Hippoglossus halibuts, with the Atlantic halibut measuring up to 4.7 m (15 ft) long,[16] and the Pacific halibut weighing up to 363 kg (800 lb).[17][1]

Many species such as flounders and spiny turbots eat smaller fish, and have well-developed teeth. These species sometimes hunt in the midwater, away from the bottom, and show fewer "extreme" adaptations than other families. The soles, by contrast, are almost exclusively bottom-dwellers (more strictly demersal), and feed on benthic invertebrates. They show a more extreme asymmetry, and may lack teeth on one side of the jaw.[1]

Development

[edit]

Flatfishes lay eggs that hatch into larvae resembling typical, symmetrical, fish. These are initially elongated, but quickly develop into a more rounded form. The larvae typically have protective spines on the head, over the gills, and in the pelvic and pectoral fins. They also possess a swim bladder, and do not dwell on the bottom, instead dispersing from their hatching grounds as ichthyoplankton.[1] Bilaterally symmetric fish such as goldfish maintain balance using a system within their inner ears which involves the otolith, but larval and metamorphizing flatfish require visible light (such as sunlight) to properly orient themselves.[18]

The length of the planktonic stage varies between different types of flatfishes, but through the influence of thyroid hormones,[19] they eventually begin to metamorphose into the adult form. One of the eyes migrates across the top of the head and onto the other side of the body, leaving the fish blind on one side. The larva also loses its swim bladder and spines, and sinks to the bottom, laying its blind side on the underlying surface.[20][18]

Hybrids

[edit]Hybrids are well known in flatfishes. The Pleuronectidae have the largest number of reported hybrids of marine fishes.[21] Two of the most famous intergeneric hybrids are between the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) and European flounder (Platichthys flesus) in the Baltic Sea,[22] and between the English sole (Parophrys vetulus) and starry flounder (Platichthys stellatus) in Puget Sound. The offspring of the latter species pair is popularly known as the hybrid sole and was initially believed to be a valid species in its own right.[21]

Evolution

[edit]Flatfishes have been cited as dramatic examples of evolutionary adaptation. In The Blind Watchmaker, Richard Dawkins explains the flatfishes' evolutionary history as such:

...bony fish as a rule have a marked tendency to be flattened in a vertical direction.... It was natural, therefore, that when the ancestors of [flatfish] took to the sea bottom, they should have lain on one side.... But this raised the problem that one eye was always looking down into the sand and was effectively useless. In evolution this problem was solved by the lower eye 'moving' round to the upper side.[23]

Scientists have been proposing since the 1910s that flatfishes evolved from more "typical" percoid ancestors.[24] The fossil record indicated that flatfishes might have been present before the Eocene, based on fossil otoliths resembling those of modern pleuronectiforms dating back to the Thanetian and Ypresian stages (57-53 million years ago).[25] Despite this, the origin of the unusual morphology of flatfishes was enigmatic up to the 2000s, with earlier researchers having suggested that it came about as a result of saltation rather than gradual evolution through natural selection, because a partially migrated eye was considered to have been maladaptive.

This started to change in 2008 with a study on the two fossil fish genera; Amphistium and Heteronectes, which dated to about 50 million years ago. These genera retain primitive features not seen in modern types of flatfishes, such as their heads being less asymmetric than modern flatfishes, retaining one eye on each side of their heads, although the eye on one side is closer to the top of the head than on the other.[26][27] The more recently described fossil genera Quasinectes and Anorevus have been proposed to show similar morphologies and have also been classified as "stem-pleuronectiforms".[28][29] Such findings lead palaeontologist Matt Friedman to conclude that the evolution of flatfish morphology "happened gradually, in a way consistent with evolution via natural selection—not suddenly [saltationally] as researchers once had little choice but to believe."[27]

To explain the survival advantage of a partially migrated eye, it has been proposed that primitive flatfishes like Amphistium rested with the head propped up above the seafloor (a behaviour sometimes observed in modern flatfishes), enabling them to use their partially migrated eye to see things closer to the seafloor.[30] While known basal genera like Amphistium and Heteronectes support a gradual acquisition of the flatfish morphology, they were probably not direct ancestors to living pleuronectiforms, as fossil evidence[examples needed] indicate that most flatfish lineages living today were present in the Eocene and contemporaneous with them.[26] It has been suggested that the more primitive forms were eventually outcompeted.[27]

Taxonomy

[edit]Due to their highly distinctive morphology, flatfishes were previously treated as belonging to their own order, Pleuronectiformes. However, more recent taxonomic studies have found them to group within a diverse group of nektonic marine fishes known as the Carangiformes, which also includes jacks and billfish. Specifically, flatfish have been recovered to be closely related to various groups, such as the threadfins (often recovered as a sister group to flatfish), archerfish, and beachsalmons. Due to this, they are now treated as a suborder of the Carangiformes,[31][32] as represented in Eschmeyer's Catalog of Fishes.[33]

Classification

[edit]The following classification is based on Eschmeyer's Catalog of Fishes (2025):[34]

- Suborder Pleuronectoidei

- Family Polynemidae Rafinesque, 1815 (threadfins or tassel-fishes)

- Family Psettodidae Regan, 1910 (spiny turbots)

- Family Citharidae de Buen, 1935 (largescale flounders)

- Family Scophthalmidae Chabanaud, 1933 (turbots)

- Family Cyclopsettidae Campbell, Chanet, Chen, Lee & Chen, 2019 (sand whiffs or large-tooth flounders)

- Family Grammatobothidae Tongboonkua, Chanet & Chen, 2025 (small lefteye flounders)[35]

- Family Monolenidae Tongboonkua, Chanet & Chen, 2025 (deepwater lefteye flounders)[35]

- Family Taeniopsettidae Amaoka, 1969[35]

- Family Bothidae Smitt, 1892 (lefteye flounders)

- Family Paralichthyidae Regan, 1910 (sand flounders)

- Family Pleuronectidae Rafinesque, 1815 (righteye flounders)

- Family Paralichthodidae Regan, 1920 (peppered flounders)

- Family Oncopteridae Jordan & Goss, 1889 (remo flounders)

- Family Rhombosoleidae Regan, 1910 (South Pacific flounders)

- Family Achiropsettidae Heemstra, 1990 (southern flounders or armless flounders)

- Family Achiridae Rafinesque, 1815 (American soles)

- Family Samaridae Jordan & Goss, 1889 (crested flounders)

- Family Poecilopsettidae Norman, 1934 (bigeye flounders)

- Family Soleidae Bonaparte, 1833 (soles)

- Family Cynoglossidae Jordan, 1888 (tonguefishes)

Fossil taxa

[edit]The following basal fossil flatfish from the Paleogene are also known:[36]

- Genus ?†Anorevus Bannikov & Zorzin, 2020 (Early Eocene of Italy)[28]

- Genus †Eobothus Eastman, 1914 (Early Eocene of Italy)

- Genus †Heteronectes Friedman, 2008 (Middle Eocene of France)

- Genus †Imhoffius Chabanaud, 1940 (Middle Eocene of France)[37]

- Genus †Keasichthys Murray & Champagne, 2025 (Early Oligocene of Oregon, US)[38]

- Genus †Numidiopleura Gaudant & Gaudant, 1969 (Eocene of Tunisia)[37][39]

- Genus ?†Quasinectes Bannikov & Zorzin, 2019 (Early Eocene of Italy)[29]

- Family †Amphistiidae Boulenger, 1902

- Family †Joleaudichthyidae Chabanaud, 1937

Phylogeny

[edit]

There has been some disagreement whether flatfish as a whole are a monophyletic group. Some palaeontologists think that some percomorph groups unrelated to flatfishes were also "experimenting" with head asymmetry during the Eocene,[28][29] and certain molecular studies conclude that the primitive family of Psettodidae evolved their flat bodies and asymmetrical head independently of other flatfish groups.[40][41] The following phylogeny is from Lü et al. 2021; a whole-genome analysis using concatenated sequences of coding sequence (CDS) (codon1 + 2 + 3, GTRGAMMA model; codon1 + 2, GTRGAMMA model) and 4dTV (fourfold degenerate synonymous site, GTRGAMMA model) derived from 1,693 single-copy genes. Notably, Pleuronectiformes is found to be polyphyletic as seen here:[42]

| Pleuronectoidei |

|

Pleuronectiformes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, threadfins (Polynemidae) aren't universally found to be nested within the group of flatfish, as recovered by a study of ultraconserved elements from the threadfin family in Girard et al. 2022,[43] or as represented in the World Register of Marine Species,[44] where Pleuronectiformes is retained as a name for the flatfish group.[45] Numerous scientists continue to argue for a monophyletic group of all flatfish,[46] though the debate continues.[47]

Over 800 described species are placed into 16 families.[48] When they were treated as an order, the flatfishes are divided into two suborders, Psettodoidei and Pleuronectoidei, with > 99% of the species diversity found within the Pleuronectoidei.[49] The largest families are Soleidae, Bothidae and Cynoglossidae with more than 150 species each. There also exist two monotypic families (Paralichthodidae and Oncopteridae). Some families are the results of relatively recent splits. For example, the Achiridae were classified as a subfamily of Soleidae in the past, and the Samaridae were considered a subfamily of the Pleuronectidae.[9][50] The families Paralichthodidae, Poecilopsettidae, and Rhombosoleidae were also traditionally treated as subfamilies of Pleuronectidae, but are now recognised as families in their own right.[50][51][52] The Paralichthyidae has long been indicated to be paraphyletic, with the formal description of Cyclopsettidae in 2019 resulting in the split of this family as well.[48] The following is the maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree from Campbell et al. 2019, which was obtained by analyzing seven protein-coding genes. This study erected two new families to resolve the previously non-monophyletic status of Paralichthyidae and the Rhombosoleidae:[48]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The taxonomy of some groups is in need of a review. The last monograph covering the entire order was John Roxborough Norman's Monograph of the Flatfishes published in 1934. In particular, Tephrinectes sinensis may represent a family-level lineage and requires further evaluation e.g.[53] New species are described with some regularity and undescribed species likely remain.[9]

Timeline of genera

[edit]

Relation to humans

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large predatory |

| Forage |

| Demersal |

| Mixed |

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2025) |

Fishing and aquaculture

[edit]Flatfish are commonly fished using bottom trawls.[54][55] Large species such as the halibuts are specifically targeted by fisheries, resulting in heavy fishing pressures and bycatch.[56][57][58] Some species are aquacultured, such as the tonguefish Cynoglossus semilaevis.[59][60]

As food

[edit]Flatfish is considered a whitefish[61] because of the high concentration of oils within its liver. Its lean flesh makes for a unique flavor that differs from species to species. Methods of cooking include grilling, pan-frying, baking and deep-frying.

-

The European plaice is the principal commercial flatfish in Europe.

-

American soles are found in both freshwater and marine environments of the Americas.

-

Halibut are the largest of the flatfishes, and provide lucrative fisheries.

-

The turbot is a large, left-eyed flatfish found in sandy shallow coastal waters around Europe.

-

Flatfish (left‐eyed flounder)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Chapleau, Francois; Amaoka, Kunio (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. xxx. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- ^ Scudder, Samuel Hubbard (1882). Nomenclator Zoologicus: An Alphabetical List of All Generic Names that Have Been Employed by Naturalists for Recent and Fossil Animals from the Earliest Times to the Close of the Year 1879 ... U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Campbell, Matthew A.; Chanet, Bruno; Chen, Jhen-Nien; Lee, Mao-Ying; Chen, Wei-Jen (2019). "Origins and relationships of the Pleuronectoidei: Molecular and morphological analysis of living and fossil taxa" (PDF). Zoologica Scripta. 48 (5): 640–656. doi:10.1111/zsc.12372. ISSN 1463-6409. S2CID 202856805.

- ^ Jamieson, A.J., and Yancey, P. H. (2012). On the Validity of the Trieste Flatfish: Dispelling the Myth. The Biological Bulletin 222(3): 171-175

- ^ Munroe, T.A.; and Hashimoto, J. (2008). A new Western Pacific Tonguefish (Pleuronectiformes: Cynoglossidae): The first Pleuronectiform discovered at active Hydrothermal Vents. Zootaxa 1839: 43–59.

- ^ Duplain, R.R.; Chapleau, F; and Munroe, T.A. (2012). A New Species of Trinectes (Pleuronectiformes: Achiridae) from the Upper Río San Juan and Río Condoto, Colombia. Copeia 2012 (3): 541-546.

- ^ Kottelat, M. (1998). Fishes of the Nam Theun and Xe Bangfai basins, Laos, with diagnoses of twenty-two new species (Teleostei: Cyprinidae, Balitoridae, Cobitidae, Coiidae and Odontobutidae). Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwat. 9(1):1-128.

- ^ Monks, N. (2007). Freshwater flatfish, order Pleuronectiformes. Archived 2014-08-15 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 18 May 2014

- ^ a b c Randall, J. E. (2007). Reef and Shore Fishes of the Hawaiian Islands. ISBN 1-929054-03-3

- ^ Elst, R. van der (1997) A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of South Africa. ISBN 978-1868253944

- ^ Debelius, H. (1997). Mediterranean and Atlantic Fish Guide. ISBN 978-3925919541

- ^ Practical Fishkeeping (22 May 2012) Video: Tiny sole mimics a flatworm. Archived 2014-05-17 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ Australian Museum (5 November 2010). This week in Fish: Flatworm mimic and shark teeth. Archived 2013-02-26 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ Hanlon, R.T.; Warson, A.C.; and Barbosa, A. (2010). A "Mimic Octopus" in the Atlantic: Flatfish Mimicry and Camouflage by Macrotritopus defilippi. The Biological Bulletin 218(1): 15-24

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Tarphops oligolepis". FishBase.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Hippoglossus hippoglossus". FishBase.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Hippoglossus stenolepis". FishBase.

- ^ a b Jabr, Feris (7 May 2014). "The Improbable—but True—Evolutionary Tale of Flatfishes". pbs.org. PBS NOVA. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ Schreiber, Alexander M. (2013). "Flatfish: an asymmetric perspective on metamorphosis". Curr Top Dev Biol. 103: 167–94. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385979-2.00006-X. PMID 23347519.

- ^ Bao, Baolong (2022). Flatfish Metamorphosis (1 ed.). Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-7859-3. ISBN 978-981-19-7858-6.

- ^ a b Garrett, D.L.; Pietsch, T.W.; Utter, F.M.; and Hauser, L. (2007). The Hybrid Sole Inopsetta ischyra (Teleostei: Pleuronectiformes: Pleuronectidae): Hybrid or Biological Species? American Fisheries Society 136: 460–468

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Platichthys flesus (Linnaeus, 1758).. Retrieved 18 May 2014

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1991). The Blind Watchmaker. London: Penguin Books. p. 92. ISBN 0-14-014481-1.

- ^ Regan C.T. (1910). "The origin and evolution of the Teleostean fishes of the order Heterosomata". Annals and Magazine of Natural History 6(35): p. 484-496. doi.org/10.1080/00222931008692879

- ^ Schwarzhans W. (1999). "A comparative morphological treatise of recent and fossil otoliths of the order Pleuronectiformes". Piscium Catalogus. Otolithi Piscium 2. doi:10.13140/2.1.1725.5043

- ^ a b Friedman M. (2008). "The evolutionary origin of flatfish asymmetry". Nature 454(7201): p. 209–212. doi:10.1038/nature07108

- ^ a b c "Odd Fish Find Contradicts Intelligent-Design Argument". National Geographic. July 9, 2008. Archived from the original on July 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ^ a b c Bannikov A.F. & Zorzin R (2019). "A new genus and species of incertae sedis percomorph fish (Perciformes) from the Eocene of Bolca in northern Italy, and a new genus for Psettopsis latellai Bannikov, 2005". Studi e ricerche sui giacimenti terziari di Bolca: p. 5-15.

- ^ a b c Bannikov A.F. & Zorzin R. (2020). "A new genus and species of percomorph fish ("stem pleuronectiform") from the Eocene of Bolca in northern Italy". Miscellanea Paleontologica 17: p. 5–14

- ^ Janvier P. (2008). "Squint of the fossil flatfish". Nature 454(7201): p. 169–170

- ^ Girard, Matthew G.; Davis, Matthew P.; Smith, W. Leo (2020-05-08). "The Phylogeny of Carangiform Fishes: Morphological and Genomic Investigations of a New Fish Clade". Copeia. 108 (2): 265–298. doi:10.1643/CI-19-320. ISSN 0045-8511.

- ^ Shi, Wei; Chen, Shixi; Kong, Xiaoyu; Si, Lizhen; Gong, Li; Zhang, Yanchun; Yu, Hui (2018-05-25). "Flatfish monophyly refereed by the relationship of Psettodes in Carangimorphariae". BMC Genomics. 19 (1): 400. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4788-5. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 5970519. PMID 29801430.

- ^ Fricke, Ron; Fong, Jon David. "GENERA/SPECIES BY FAMILY/SUBFAMILY IN Eschmeyer's Catalog of Fishes". researcharchive.calacademy.org. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ Fricke, R.; Eschmeyer, W. N.; Van der Laan, R. (2025). "ESCHMEYER'S CATALOG OF FISHES: CLASSIFICATION". California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2025-10-22.

- ^ a b c Tongboonkua, Pakorn; Chanet, Bruno; Chen, Wei-Jen. "Integrated Molecular and Morphological Analyses Resolve Long-Standing Classification Challenges in the Sinistral Flatfish Family Bothidae (Teleostei: Carangiformes)". Zoologica Scripta. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1111/zsc.70020. ISSN 1463-6409.

- ^ Laan, Richard van der (2018-10-11). "Family-group names of fossil fishes". European Journal of Taxonomy (466). doi:10.5852/ejt.2018.466. ISSN 2118-9773.

- ^ a b Chanet, Bruno; Schultz, Orwin (1994). "Pleuronectiform fishes from the Upper Badenian (Middle Miocene) of St. Margarethen (Austria)". Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien (96): 95–115.

- ^ Murray, Alison M.; Champagne, Donald E. (January 2025). "A new species of early Oligocene flatfish (Pleuronectiformes) from Oregon, USA". Geological Magazine. 162 e22. Bibcode:2025GeoM..162E..22M. doi:10.1017/S0016756825100125. ISSN 0016-7568.

- ^ Campbell, Matthew A.; Chanet, Bruno; Chen, Jhen-Nien; Lee, Mao-Ying; Chen, Wei-Jen (2019). "Origins and relationships of the Pleuronectoidei: Molecular and morphological analysis of living and fossil taxa". Zoologica Scripta. 48 (5): 640–656. doi:10.1111/zsc.12372. ISSN 1463-6409.

- ^ Campbell M.A., Chen W-J. & López J.A. (2013). "Are flatfishes (Pleuronectiformes) monophyletic?". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 69(3): p. 664-673. doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.07.011

- ^ Campbell M.A., López J.A., Satoh T.P., Chen W-J. & Miya M. (2014). "Mitochondrial genomic investigation of flatfish monophyly". Gene 551(2): p. 176-182. doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2014.08.053

- ^ Zhenming Lü; Li Gong; Yandong Ren; Yongjiu Chen; Zhongkai Wang; Liqin Liu; Haorong Li; Xianqing Chen; Zhenzhu Li; Hairong Luo; Hui Jiang; Yan Zeng; Yifan Wang; Kun Wang; Chen Zhang; Haifeng Jiang; Wenting Wan; Yanli Qin; Jianshe Zhang; Liang Zhu; Wei Shi; Shunping He; Bingyu Mao; Wen Wang; Xiaoyu Kong; Yongxin Li (19 April 2021). "Large-scale sequencing of flatfish genomes provides insights into the polyphyletic origin of their specialized body plan". Nature Genetics. 53 (5): 742–751. doi:10.1038/s41588-021-00836-9. PMC 8110480. PMID 33875864.

- ^ Matthew G. Girard; Matthew P. Davis; Carole C. Baldwin; Agnès Dettaï; Rene P. Martin; W. Leo Smith (12 January 2022). "Molecular phylogeny of the threadfin fishes (Polynemidae) using ultraconserved elements" (PDF). Fish Biology. 100 (3): 793–810. Bibcode:2022JFBio.100..793G. doi:10.1111/jfb.14997. PMID 35137410.

- ^ Bailly N (ed.). "Polynemidae Rafinesque, 1815". FishBase. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ Bailly N (ed.). "Pleuronectiformes". FishBase. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ Duarte-Ribeiro E, Rosas-Puchuri U, Friedman M, Woodruff G.C., Hughes L.C., Carpenter K.E., White W.T., Pogonoski J.J., Westneat M, Diaz de Astarloa J.M., Williams J.T., Santos M.D., Domínguez-Domínguez O, Ortí G, Arcila D & Betancur-R R. (2024). "Phylogenomic and comparative genomic analyses support a single evolutionary origin of flatfish asymmetry". Nature Genetics 56: p. 1069-1072. doi.org/10.1038/s41588-024-01784-w

- ^ Lü, Zhenming; Li, Haorong; Jiang, Hui; Luo, Hairong; Wang, Wen; Kong, Xiaoyu; Li, Yongxin (2024-05-27). "Reply to: Phylogenomic and comparative genomic analyses support a single evolutionary origin of flatfish asymmetry". Nature Genetics. 56 (6): 1073–1074. doi:10.1038/s41588-024-01783-x. PMID 38802565. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Matthew A.; Chanet, Bruno; Chen, Jhen-Nien; Lee, Mao-Ying; Chen, Wei-Jen (2019). "Origins and relationships of the Pleuronectoidei: Molecular and morphological analysis of living and fossil taxa" (PDF). Zoologica Scripta. 48 (5): 640–656. doi:10.1111/zsc.12372. ISSN 0300-3256. S2CID 202856805.

- ^ Nelson, Joseph S.; Grande, Terry C.; Wilson, Mark V. H. (2016-03-28). Fishes of the world. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. OCLC 958002567.

- ^ a b Cooper, J.A.; and Chapleau, F. (1998). Monophyly and intrarelationships of the family Pleuronectidae (Pleuronectiformes), with a revised classification. Fish. Bull. 96 (4): 686–726.

- ^ Nelson, J. S. (2006). Fishes of the World (4 ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- ^ J. S. Nelson; T. C. Grande; M. V. H. Wilson (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Wiley. p. 752. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. Archived from the original on 2019-04-08. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Hoshino, Koichi (2001-11-01). "Monophyly of the Citharidae (Pleuronectoidei: Pleuronectiformes: Teleostei) with considerations of pleuronectoid phylogeny". Ichthyological Research. 48 (4): 391–404. Bibcode:2001IchtR..48..391H. doi:10.1007/s10228-001-8163-0. ISSN 1341-8998. S2CID 46318428.

- ^ Segura-Garcia, Iris; Soe, Sabai; Tun, NYO-NYO; Box, Stephen (2021). "Beyond Bycatch: The Species Diversity of Tonguesole (Pleuronectiformes: Cynoglossidae) in Coastal Fisheries of the Tanintharyi Region, Southern Myanmar". Asian Fisheries Science. 34: 23–33. doi:10.33997/j.afs.2021.34.1.003. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ Zhang, Jinyong; Cui, Xiaoyu; Lin, Lin; Liu, Yuan; Ye, Jinqing; Zhang, Weiyue; Li, Hongjun (30 April 2025). "Unraveling Fish Community Diversity and Structure in the Yellow Sea: Evidence from Environmental DNA Metabarcoding and Bottom Trawling". Animals. 15 (9): 1283. doi:10.3390/ani15091283. PMC 12070852. PMID 40362097.

- ^ Szymkowiak, Marysia; Marrinan, Sarah; Kasperski, Stephen (2020). "The Pacific Halibut, Hippoglossus stenolepis, and Sablefish, Anoplopoma fimbria, Individual Fishing Quota Program: A Twenty-year Retrospective" (PDF). Marine Fisheries Review. 82 (1–2): 1–16. doi:10.7755/MFR.82.1-2.1. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ "Collaborative Pacific Halibut, Hippoglossus stenolepis, Bycatch Control by Canada and the United States" (PDF). Marine Fisheries Review. 66. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ Figus, Elizabeth; Criddle, Keith R. (March 1, 2019). "Characterizing preferences of fishermen to inform decision-making: A case study of the Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) fishery off Alaska". PLOS. 14 (3) e0212537. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1412537F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212537. PMC 6396916. PMID 30822324.

- ^ Hu, Yuanri; Li, Yangzhen; Li, Zhongming; Chen, Changshan; Zang, Jiajian; Li, Yuwei; Kong, Xiangqing (December 2020). "Novel insights into the selective breeding for disease resistance to vibriosis by using natural outbreak survival data in Chinese tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis)". Aquaculture. 529 735670. Bibcode:2020Aquac.52935670H. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735670. S2CID 224900889.

- ^ Li, Yangzhen; Hu, Yuanri; Yang, Yingming; Zheng, Weiwei; Chen, Changshan; Li, Zhongming (January 2021). "Selective breeding for juvenile survival in Chinese tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis): Heritability and selection response". Aquaculture. 531 735901. Bibcode:2021Aquac.53135901L. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735901. S2CID 224878642.

- ^ "Flatfish BBC".

Further reading

[edit]- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-17.

- Gibson, Robin N (Ed) (2008) Flatfishes: biology and exploitation. Wiley.

- Munroe, Thomas A (2005) "Distributions and biogeography." Flatfishes: Biology and Exploitation: 42–67.

External links

[edit]Flatfish

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Classification

Etymology and Common Names

The term "flatfish" is an English compound word first recorded in 1710, derived from "flat," meaning level or even, which originates from Old English flæt, and "fish," from Old English fisc.[7] This descriptive name reflects the group's characteristic laterally compressed, flattened body adapted for bottom-dwelling.[8] In scientific nomenclature under the Linnaean system, flatfish belong to the order Pleuronectiformes, a name coined from the genus Pleuronectes (Greek pleura, "side," + nēktēs, "swimmer"), alluding to their asymmetrical, side-oriented swimming.[9] Common names for flatfish vary by region, species, and cultural context, often emphasizing size, habitat, or culinary value rather than strict taxonomy. In North America, "flounder" serves as a broad term for many small to medium species, such as the summer flounder (Paralichthys dentatus) along the Atlantic coast, while "halibut" denotes larger ones like the Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis), the biggest flatfish reaching over 2 meters.[10] "Sole" typically refers to members of the Soleidae family, including the Dover sole (Solea solea), valued in fisheries. In Europe, "plaice" commonly names the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa), a key food fish in the North Sea, and "turbot" identifies the premium Scophthalmus maximus, known for its firm flesh.[11] Other regional variants include "dab" for small species like the European dab (Limanda limanda) in the Northeast Atlantic.[12] Cultural naming influences add diversity, particularly in indigenous Pacific communities where local flatfish hold traditional and mythological significance. For instance, among Pacific Northwest tribes like the Kwakiutl and Haida, halibut features prominently in origin stories and art as a symbol of prosperity, with names reflecting their role in sustenance and rituals, though specific terms vary by dialect and are often tied to oral traditions rather than standardized English equivalents.[13]Higher Classification

Flatfish belong to the phylum Chordata, subphylum Vertebrata, class Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes), and are classified in the order Pleuronectiformes.[2] Although some recent phylogenetic studies have proposed elevating Pleuronectiformes to a suborder within a broader percomorph order, it remains widely recognized as an order in authoritative databases.[11] The order Pleuronectiformes encompasses 16 families, approximately 130 genera, and over 800 species, making it one of the most diverse groups of marine teleosts.[14] Key diagnostic characteristics of the order include a highly asymmetric body plan, with both eyes positioned on one side of the head due to ocular migration during ontogeny, and elongate dorsal and anal fins that form continuous margins around the body.[11] Among the families, Pleuronectidae (righteye flounders) includes genera such as Hippoglossus (e.g., Atlantic halibut) and Pleuronectes (e.g., plaice), while Soleidae comprises true soles like Solea solea (common sole), characterized by their left-eyed orientation and elongated bodies.[15][16] Other notable families include Bothidae (lefteye flounders) and Scophthalmidae (turbots), contributing to the order's ecological and commercial diversity.[17]Phylogeny and Relationships

The order Pleuronectiformes, comprising flatfishes, has been the subject of extensive phylogenetic scrutiny using both molecular and morphological data, with recent analyses largely supporting its monophyly within the percomorph fishes. Early molecular studies based on mitochondrial ribosomal genes, such as 12S and 16S rRNA, provided initial evidence for monophyletic grouping, though some analyses suggested paraphyly due to the divergent position of certain taxa.[18] However, multi-locus approaches incorporating nuclear and mitochondrial sequences have resolved these debates, confirming Pleuronectiformes as a cohesive clade nested within Carangimorpharia, sister to groups like the jackfishes (Carangoidea).[19] Within Pleuronectiformes, two suborders are recognized: the basal Psettodoidei, containing the single family Psettodidae and genus Psettodes, and the more derived Pleuronectoidei, which encompasses the majority of flatfish diversity across 13 families.[20] Mitogenomic analyses show varying positions for Psettodes, with some earlier studies placing it as the earliest diverging lineage, characterized by primitive traits like symmetrical eyes in juveniles and a less pronounced cranial asymmetry compared to Pleuronectoidei members, while recent analyses (as of 2025) cluster Psettodidae with families like Rhombosoleidae, Achiridae, Soleidae, Cynoglossidae, and Samaridae after more derived groups.[21] In Pleuronectoidei, inter-family relationships reveal a complex radiation; for instance, molecular phylogenies based on concatenated mitochondrial genes show the Bothidae (lefteye flounders) as sister to a clade including Scophthalmidae and Pleuronectidae, while Cynoglossidae (tonguefishes) form a more distant branch. A 2025 mitogenomic analysis of 111 species confirms monophyly and resolves some relationships, with Paralichthyidae and Pleuronectidae clustering basally, followed by Cyclopsettidae and Bothidae.[22][23] These connections are further corroborated by phylogenomic datasets addressing gene tree discordance, which highlight convergent adaptations in asymmetry across families but uphold distinct evolutionary lineages.[19] Debates persist regarding the precise sister group to Pleuronectiformes among percomorphs, with some mitogenomic evidence suggesting proximity to Tetraodontiformes (pufferfishes), though broader datasets favor a position within Carangimorpharia without direct adjacency to tetraodontiforms.[20] Hybridization occurs between closely related genera, such as Pleuronectes and Platichthys, indicating potential gene flow that could influence phylogenetic signals in borderline taxa, though such events are rare and do not undermine overall monophyly.[24] Fossil evidence aligns with these molecular trees by supporting an early divergence of psettodids around the Eocene.Fossil Record

The fossil record of flatfish (order Pleuronectiformes) is relatively sparse, primarily due to their benthic lifestyle, which limits rapid burial and preservation in sedimentary deposits compared to pelagic or nektonic fishes.[25] This bottom-dwelling habit results in fewer exceptional preservation sites, with most known specimens derived from marine lagerstätten featuring fine-grained sediments conducive to detailed fossilization. Otolith-based evidence suggests possible origins in the Late Paleocene to Early Eocene (approximately 57–53 million years ago), but definitive skeletal fossils appear only in the Eocene.[26] The earliest well-documented flatfish fossils date to the early Eocene, around 50 million years ago, from sites such as the Monte Bolca lagerstätte in northern Italy, a renowned Eocene deposit yielding exceptionally preserved fish assemblages.[27] Notable early taxa include Amphistium bifrons, first described in the 18th century but re-evaluated in modern studies for its primitive flatfish traits, and Heteronectes chaneti, a newly recognized genus exhibiting intermediate cranial asymmetry. These fossils display partial eye migration, with one eye positioned dorsally but not fully migrated to the upper side of the head, providing key evidence for the gradual evolution of the characteristic flatfish body plan in stem-group representatives. Pre-Eocene records remain elusive, with no confirmed skeletal fossils from the Cretaceous or earlier, underscoring a post-K-Pg boundary diversification.[26] Subsequent Eocene and Oligocene deposits reveal increasing diversity, though gaps persist through the Paleogene due to taphonomic biases favoring nearshore or reef-associated environments.[28] For instance, Eobothus species from Eocene strata represent early bothid-like forms, bridging primitive and more derived morphologies. Recent discoveries, such as Keasichthys oregonensis, a new primitive species from the early Oligocene Keasey Formation in Oregon, USA (as of 2025), highlight ongoing efforts to fill transitional records between Eocene origins and Miocene radiations.[28] These finds, preserved in deep-water silty shales, demonstrate affinities to stem pleuronectiforms and aid in reconstructing phylogenetic relationships among early flatfish lineages.[28]Anatomy and Physiology

Body Structure and Adaptations

Flatfish are characterized by profound bilateral asymmetry, a defining feature of their body plan that distinguishes them from most other vertebrates. In adults, both eyes are positioned on one side of the head, known as the ocular or eyed side, while the opposite side remains blind and typically features reduced pigmentation. This arrangement results from a developmental process where one eye migrates across the skull to join the other during metamorphosis, enabling the fish to lie flat on the seabed with the eyed side facing upward for environmental monitoring. The body undergoes significant dorso-ventral compression, reducing its thickness to approximately 1-3 cm in many species, which facilitates a low-profile benthic existence and minimizes visibility to predators.[29][30] The skin of flatfish is highly adapted for camouflage, featuring specialized pigment cells called chromatophores that allow rapid adjustments in color and pattern to blend with surrounding substrates. These cells, including melanophores, xanthophores, and iridophores, expand or contract under neural and hormonal control, enabling the fish to mimic sandy, muddy, or rocky bottoms with remarkable precision—for instance, the peacock flounder (Bothus lunatus) can alter its mottled patterns within minutes to match complex seafloor textures. This adaptive coloration serves primarily as an anti-predator mechanism, enhancing survival by reducing detection in visually oriented environments. The eyed side displays vibrant, variable pigmentation, while the blind side remains pale to avoid contrasting with the substrate when flipped.[31] Locomotion in flatfish relies on modified fins suited to their asymmetrical, flattened form, emphasizing short bursts of movement over sustained swimming. Enlarged pectoral fins on the eyed side function like limbs, providing lift, stability, and propulsion during maneuvers across the seabed, often in coordination with undulating waves along the elongated dorsal and anal fins that act as "fin-feet" for crawling or walking. This fin-based gait, observed in species like the southern flounder (Paralichthys lethostigma), resembles that of arthropods, with metachronal waves propagating from anterior to posterior to generate thrust against the substrate. In many flatfish, the caudal fin is reduced or fan-like, limiting open-water swimming efficiency but optimizing bottom-dwelling efficiency; for example, soles in the family Soleidae exhibit particularly diminutive caudal fins, relying almost entirely on pectoral and body undulations for progression.[33][34]Sensory Systems

Flatfish possess a highly specialized visual system adapted to their benthic lifestyle, where one eye migrates during metamorphosis to join the other on the dorsal (eyed) side of the body, enabling both eyes to face upward while the fish lies flat on the substrate.[35] This ocular migration results in enhanced binocular vision, allowing for depth perception and stereoscopic scanning of the water column above for predators and prey.[36] Some species, such as the olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus), exhibit color vision capabilities, with cone photoreceptors sensitive to wavelengths that aid in detecting camouflaged or colored prey against varied backgrounds.[37] The visual system integrates briefly with camouflage, as the upward-facing eyes assess substrate patterns to trigger rapid color and texture adjustments on the eyed side.[35] The chemical senses in flatfish are prominently developed to compensate for limited mobility and visibility in sandy or muddy habitats. Olfactory organs are enlarged and asymmetric, with the rosette on the eyed side larger than on the blind side, enhancing detection of chemical cues from distant sources in the water column.[38] This adaptation supports orientation and localization in low-light conditions. Taste buds are distributed extensively across the body surface, including the head, fins, and eyed side, forming a gustatory network that probes sediments for buried prey.[39] In species like the Remo flounder (Rhombosolea plebeia), specialized structures such as the gustatory stalk on the snout contain dense clusters of these taste buds, innervated by cranial nerves to sense amino acids and other chemicals indicating food availability just below the surface.[39] The lateral line system in flatfish exhibits modifications suited to their flattened morphology, with bilateral asymmetry and reductions on the blind side to streamline the body against the substrate.[40] Despite this reduction, the system remains sensitive to low-frequency water vibrations and pressure changes, primarily through canal neuromasts on the head and trunk that detect nearby movements.[40] This mechanosensory capability is crucial for predator avoidance, as flatfish can sense approaching threats via hydrodynamic disturbances even when camouflaged and stationary.[40]Metamorphosis and Development

Flatfish larvae hatch as bilaterally symmetric, planktonic forms resembling typical fish larvae, with eyes positioned on opposite sides of the head and a vertically oriented body. This pelagic stage allows dispersal in the water column, where larvae feed primarily on zooplankton while undergoing rapid growth. The duration of the larval stage varies by species and environmental factors such as temperature, typically spanning 30 to 100 days; for example, in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus), metamorphosis begins around 46 days post-hatching.[41][42] Metamorphosis marks a dramatic transition from the symmetric larval form to the asymmetric adult, driven primarily by surges in thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). These hormones orchestrate craniofacial remodeling, including the migration of one eye across the dorsal surface to join the other on the same side of the head, which typically occurs over several days to weeks. Concurrently, the body tilts toward the eyed side, the underside pigments adapt for camouflage, and the fish settles to a benthic lifestyle, abandoning the water column. Thyroid hormone signaling regulates gene expression in neural crest-derived tissues, ensuring coordinated skeletal and muscular changes that enable this asymmetry.[43][44][45] Species-level variations in metamorphosis include the direction of eye migration, resulting in either sinistral (left-eyed) or dextral (right-eyed) adults. Among the approximately 14 families of flatfish, most are monomorphic, with roughly half fixed as sinistral and the other half as dextral, though a few families like Pleuronectidae exhibit polymorphism where both forms occur within populations. This asymmetry direction is genetically determined and fixed early in development, influencing ecological adaptations such as burrowing preferences.[46][43]Ecology and Distribution

Global Distribution

Flatfish exhibit a predominantly marine distribution, with the vast majority of their over 800 recognized species occupying temperate to tropical oceanic waters worldwide, spanning from the Arctic fringes to near-Antarctic seas. Approximately 90% of these species thrive in these marine environments, reflecting their adaptation to benthic lifestyles on continental shelves and slopes. While estuarine habitats serve as transitional zones for some, true freshwater occupancy is rare, limited to a handful of species in the family Achiridae, such as those in the genus Achirus, which are endemic to riverine and coastal systems in South America.[47][48][49] The Indo-West Pacific stands out as the primary biogeographic hotspot for flatfish diversity, hosting the highest concentration of species—estimated at over 400—due to the region's expansive shallow seas, varied substrates, and historical tectonic influences that fostered speciation. This center of origin drives a longitudinal and latitudinal gradient in species richness, with abundance decreasing away from the Indo-Pacific toward polar and eastern Atlantic/Pacific margins. For instance, the South China Sea alone supports more than 125 species, underscoring the area's role as a evolutionary cradle. In contrast, temperate regions like the North Atlantic feature prominent large-bodied species such as the Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus), which ranges from Greenland to the Barents Sea on both sides of the basin.[47][50] Depth distribution aligns closely with continental shelf bathymetry for most flatfish, with the majority inhabiting waters from the surface to 200 m, where soft sediments and productivity support their demersal habits. However, certain taxa extend into deeper realms; for example, the deep-sea sole (Microstomus bathybius) in the family Pleuronectidae occurs at bathydemersal depths up to 1,800 m in the North Pacific, highlighting adaptive versatility among the order. These patterns emphasize flatfish as a group with broad but shelf-dominated occupancy, punctuated by regional endemics and occasional deep-water outliers.[51][52]Habitat Preferences

Flatfish predominantly inhabit benthic environments, favoring soft substrates such as mud and sand that facilitate burrowing for camouflage and predator avoidance.[53] Species like plaice and sole commonly occupy these sedimentary bottoms in coastal and shelf areas, where fine-grained sediments provide ideal conditions for embedding.[54] While most flatfish prefer such soft habitats, certain species, including the megrim (Lepidorhombus whiffiagonis), can also utilize rocky reefs and structured benthic zones, particularly at greater depths.[55] Many flatfish exhibit euryhaline capabilities, tolerating a wide salinity range, especially in estuarine settings. For instance, the summer flounder (Paralichthys dentatus) can endure salinities from 0 to 35 ppt, allowing it to thrive in both freshwater-influenced and fully marine conditions. Temperature preferences vary by species but generally fall within cooler ranges, with optimal conditions for growth and survival often between 10 and 20°C for temperate species like winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus).[56] These tolerances enable flatfish to occupy dynamic coastal waters influenced by seasonal and tidal fluctuations. Habitat use shows distinct vertical stratification across life stages, with juveniles typically settling in shallow coastal nurseries to avoid predators and access abundant food resources.[57] As they mature, adults migrate to deeper outer shelf areas, often beyond 100 meters, where stable conditions prevail.[58] Tides and currents play a key role in shaping these patterns, transporting larvae to suitable settlement grounds and influencing adult positioning relative to prey availability and water flow.[42]Behavior and Social Structure

Flatfish exhibit primarily solitary behavior, spending much of their time resting on the seafloor in a camouflaged state to ambush prey or avoid detection. As benthic ambush predators, they lie motionless, often partially buried in sediment, relying on their ability to blend into the substrate before launching rapid strikes at passing prey. This sit-and-wait strategy minimizes energy expenditure and leverages their flattened body for concealment.[59][60] Activity patterns vary by species and environmental conditions, with some flatfish showing diurnal tendencies while others are more nocturnal. For instance, European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) display a nocturnal period of high activity, emerging from cover to forage under low-light conditions. This temporal variation allows flatfish to exploit periods of reduced predator visibility or optimal prey availability.[61] To evade predators, flatfish employ burrowing and rapid color adaptation as key defenses. They burrow into sand or mud using undulatory movements of their body and fins, creating a thin layer of sediment cover that obscures their form and scent. Concurrently, their chromatophores enable quick color changes—often in seconds—to match the background substrate, enhancing crypsis against visual hunters. Schooling is rare among flatfish, with most species maintaining solitary habits or forming only loose, temporary aggregations during non-reproductive periods; this isolation reduces competition but heightens reliance on individual camouflage for survival.[62][59][63] Many flatfish undertake seasonal migrations, often shoreward, to reach spawning grounds, as revealed by tagging studies. Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis), for example, have been tracked moving 100–500 km or more via pop-up archival transmitting tags, with some individuals traveling up to 358 km in response to environmental cues and reproductive drives. These movements typically occur in deeper offshore waters during non-spawning seasons, shifting toward shallower coastal areas as temperatures rise.[64][65]Life History and Reproduction

Feeding and Diet

Flatfish exhibit a carnivorous diet that varies significantly across life stages, reflecting their benthic lifestyle and developmental changes. Juvenile flatfish primarily feed on zooplankton, including copepods, mysids, and other small planktonic organisms, which provide essential nutrients during early settlement in nursery habitats.[66] As they metamorphose and grow, their diet shifts to larger benthic prey, such as polychaetes, crustaceans (e.g., amphipods and decapods), mollusks, and small fish, enabling them to exploit the sediment-dwelling fauna in coastal and shelf environments.[67] This transition supports their increasing energy demands and body size, with adults often consuming a broader array of invertebrates and vertebrates to maintain growth and reproduction.[68] In species like the common sole (Solea solea), the adult diet is dominated by benthic invertebrates, particularly polychaetes and crustaceans, which comprise the majority of their intake throughout the year.[69] Foraging strategies among flatfish rely on ambush predation from their camouflaged positions on the seafloor, utilizing suction feeding facilitated by protrusible jaws that create a rapid inflow of water to capture elusive prey without overt movement.[70] Some species, such as dabs (Limanda limanda), also exhibit opportunistic scavenging behavior, taking advantage of disturbed sediments or fishery discards to supplement their diet with readily available organic matter.[71] Flatfish generally occupy mid-level trophic positions as predators, with estimated levels ranging from 3.0 to 4.0, positioning them between primary consumers and top carnivores in marine food webs.[72] Diet composition shows size-based shifts, where smaller individuals focus on lower-trophic invertebrates, while larger adults target higher-trophic prey; for instance, mature Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) frequently consume groundfish such as cod (Gadus macrocephalus), reflecting their role as apex benthic predators in deeper waters.[73] These patterns are influenced by habitat characteristics, which determine prey availability and drive regional variations in foraging efficiency.[74]Reproductive Strategies

Flatfish employ gonochoristic reproductive systems, characterized by distinct male and female sexes, with external fertilization occurring through broadcast spawning where gametes are released into the water column.[75] This strategy relies on synchronous release of eggs and sperm in aggregations to maximize fertilization success, without any form of parental care following spawning.[76] Most flatfish species are multiple batch spawners, releasing eggs in successive groups over an extended season to hedge against environmental variability. For instance, southern flounder (Paralichthys lethostigma) females typically produce 10–30 batches per spawning season, with intervals of 3–7 days between releases, allowing for protracted reproduction from autumn to winter.[77][78] Spawning behaviors involve offshore aggregations where adults migrate to deeper waters, often forming dense groups that facilitate group spawning, typically at night to reduce predation risk on gametes.[79] These events occur in specific grounds, such as the pelagic zones over continental shelves, with sex ratios sometimes skewed toward males in exploited populations; for example, southern flounder stocks influenced by warmer nursery temperatures (as of 2025) can exhibit ratios as imbalanced as 15:1 male to female due to climate-driven sex determination and differential fishing pressure targeting larger females.[80] Fecundity in flatfish is notably high to compensate for high larval mortality, with females producing large numbers of small, pelagic eggs that remain buoyant and drift in the water column before hatching and settlement. Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) exemplify this, with mature females capable of releasing up to 4 million eggs annually across multiple batches, proportional to body size and condition.[79][81] Following spawning, the eggs develop into planktonic larvae that disperse widely, briefly referenced here as initiating the metamorphic phase.[79]Growth and Lifespan

Flatfish display rapid somatic growth immediately following metamorphosis, with rates that are particularly high during the juvenile phase before decelerating toward an asymptotic maximum length. This pattern is commonly described using the von Bertalanffy growth function, which models length at age , where represents the theoretical maximum length, is the growth coefficient, and is the hypothetical age at zero length. For instance, in southern flounder (Paralichthys lethostigma), females approach an asymptotic length of approximately 66 cm, while males reach about 31 cm, reflecting sex-specific differences in growth trajectories. Sexual maturity in flatfish typically occurs between 2 and 5 years of age, often at lengths of 20-35 cm depending on species and sex, with environmental factors such as water temperature and population density playing key roles in timing. In North Sea plaice (Pleuronectes platessa), males reach 50% maturity at around 22 cm and ages 2-3 years, while females mature at about 34 cm and ages 4-5 years; warmer temperatures and higher densities can accelerate this process by altering energy allocation toward reproduction. These timelines ensure that individuals contribute to reproduction before reaching larger sizes, balancing growth with reproductive investment.[82][83] Lifespans among flatfish species generally range from 10 to 20 years, though larger species can exceed 50 years, allowing for extended periods of growth and reproduction. For example, plaice commonly live 15-20 years but can reach 30 years, while Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides) demonstrate longevity up to 50 years or more, supported by validated age readings from otoliths. This variability underscores the adaptability of flatfish life histories to diverse habitats and exploitation pressures.[84][85]Evolutionary History

Origins and Early Evolution

The origins of flatfish (order Pleuronectiformes) trace back to symmetric-bodied ancestors within the diverse clade Percomorpha, a group of ray-finned fishes that underwent rapid diversification during the Late Cretaceous, approximately 100 million years ago (mya).[86] These early percomorphs were upright-swimming, bilaterally symmetric teleosts adapted to pelagic or near-shore marine environments, lacking the characteristic asymmetry of modern flatfish.[87] The monophyly of Pleuronectiformes has been supported by phylogenetic analyses, with the crown group estimated to have emerged around 54–69 mya in the early Paleogene, though more recent genomic studies suggest a polyphyletic origin with independent evolution of asymmetry in suborders Psettodoidei (~80 mya) and Pleuronectoidei (~76 mya) from different percoid ancestors near the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary.[88][89] This debate highlights ongoing uncertainties in flatfish phylogeny, with some 2024 analyses reaffirming a single origin.[90] The evolution of eye migration, a hallmark of flatfish asymmetry, arose as an adaptation to life on the dimly lit seafloor, where burying in sediment and ambushing prey from a flattened posture conferred significant predatory advantages.[91] This transition from vertical swimming to horizontal bottom-dwelling was driven by selective pressures favoring enhanced camouflage and binocular vision on one side of the body, allowing better detection of prey and predators in low-light conditions. Genetically, this process involves the re-expression of the nodal-lefty-pitx2 signaling pathway during metamorphosis, with mutations in genes like pitx2 influencing left-right asymmetry and orbital repositioning.[46] Studies of flatfish genomes reveal accelerated evolutionary rates in asymmetry-related loci, underscoring the genetic underpinnings of this rapid innovation.[89] Major evolutionary transitions in flatfish involved a profound remodeling from symmetric, upright ancestors to dorsoventrally flattened forms, facilitated by thyroid hormone-regulated metamorphosis that alters cranial and postural morphology.[43] In basal lineages, such as the genus Psettodes, this metamorphosis remains incomplete, with partial eye migration and retention of some bilateral symmetry, reflecting an intermediate stage in the progression to the extreme asymmetry seen in derived taxa.[92] Fossil evidence from the Eocene, including transitional forms like Heteronectes, documents these early stages, showing partial eye migration while preserving upright swimming capabilities.[93]Key Evolutionary Adaptations

The evolution of asymmetry in flatfish represents a profound adaptation to a benthic lifestyle, characterized by a stepwise migration of one eye across the dorsal surface of the skull during metamorphosis, accompanied by extensive remodeling of the cranium and vertebral column. This process transforms the bilaterally symmetric larval form into an adult with both eyes positioned on the uppermost side, enabling surveillance of the environment while the body lies flat on the substrate. The cranial asymmetry arises gradually through incremental changes in orbital position and skeletal twisting, allowing the fish to maintain visual acuity without complete loss of function during development. This asymmetry confers significant ecological advantages, particularly enhanced camouflage through body flattening and color-matching to the seafloor, which reduces detection by predators and facilitates ambush predation on benthic prey. However, it imposes costs, including reduced swimming efficiency due to the twisted body plan, which limits sustained open-water locomotion compared to symmetrical teleosts and increases energy expenditure during vertical movements. These trade-offs highlight how selection pressures favored traits optimizing survival in demersal habitats, where ambush and concealment outweigh pelagic mobility.[29] Body flattening in flatfish illustrates parallel evolution with unrelated lineages, such as skates and rays (batoids), where dorsoventral compression also evolved for bottom-dwelling, but flatfish uniquely exhibit unilateral eye migration among teleosts, distinguishing their adaptation from the dorsally positioned, symmetric eyes of elasmobranchs. Recent genomic studies from the 2020s, including analyses of 11 flatfish species, provide evidence for the evolutionary origins of asymmetry, with some supporting a single origin within the Carangaria clade shortly after the K-Pg mass extinction (~66 mya) and others proposing independent origins in Late Cretaceous ancestors, driven by integrated genetic networks that accelerated phenotypic diversification and enabled exploitation of vacated benthic niches. Phylogenomic analyses further inform this debate, identifying key regulatory genes underlying the trait's evolution.[91][29][89][90]Timeline of Major Genera

The fossil record and molecular clock analyses indicate that flatfish (Pleuronectiformes) genera began diversifying in the Eocene, with the earliest skeletal fossils appearing around 50 million years ago (Ma) in the early Eocene, following the initial evolution of the asymmetrical body plan near the Paleocene-Eocene boundary.[94] This early phase saw the emergence of basal lineages, such as in the family Bothidae, with genera like Eobothus documented from Eocene deposits.[95] The global cooling during the Eocene-Oligocene transition approximately 34 Ma drove expansions into temperate regions, triggering an Oligocene radiation that increased genus-level diversity, particularly among righteye flounders (Pleuronectoidei).[28] Families like Scophthalmidae first appeared during this period, around 35 Ma, adapting to cooler coastal environments.[96] The Miocene (23–5 Ma) marked a major diversification phase, with many extant genera originating as ocean currents and temperatures fluctuated, enabling wider distributions. Soleidae, already present since the Middle Eocene (~45–40 Ma), saw the rise of genera like Solea in the Lower Miocene (~23–20 Ma).[97] Similarly, Pleuronectidae diversified, with Hippoglossoides appearing in the Middle Miocene (~15 Ma).[98] Bothidae expanded in the Middle Miocene as well (~15–11 Ma), reflecting adaptations to subtropical and tropical shelves.[99] Genus-level extinctions occurred during Miocene warming intervals, such as the Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (~17–14 Ma), when some Eocene-origin lineages declined in favor of more specialized forms.[97] During the Pleistocene (2.58–0.01 Ma), glacial-interglacial cycles further shaped modern genera, promoting adaptations to variable coastal habitats and leading to regional radiations without major new genus origins. Molecular estimates place the crown ages of many living genera in this epoch, with post-glacial recolonizations enhancing diversity in northern temperate zones.[100]| Genus | Family | Approximate First Appearance | Geological Period | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eobothus | Bothidae | ~50 Ma | Early Eocene | Basal lefteye form; otoliths and skeletons from Italy.[95] |

| †Cynoglossus-like | Cynoglossidae | ~48 Ma | Middle Eocene | Early tongue sole relatives.[97] |

| Solea | Soleidae | ~23–20 Ma | Lower Miocene | Diversification in European shelves.[101] |

| Hippoglossoides | Pleuronectidae | ~15 Ma | Middle Miocene | Righteye flounder in Pacific deposits.[102] |

| Bothus | Bothidae | ~15–11 Ma | Middle Miocene | Expansion in tropical regions.[99] |

| Scophthalmus | Scophthalmidae | ~35 Ma | Oligocene | Temperate turbot lineage post-cooling.[96] |

| Platichthys | Pleuronectidae | ~15–11 Ma | Middle Miocene | Flounder adaptations.[103] |

| Limanda | Pleuronectidae | ~5 Ma | Late Miocene–Pliocene | Northern expansions.[97] |

| Pseudopleuronectes | Pleuronectidae | <2.58 Ma | Pleistocene | Modern sand dab forms via glacial cycles.[100] |

| Verasper | Pleuronectidae | <2.58 Ma | Pleistocene | Recent diversification in Asia.[104] |

Human Interactions

Commercial Fishing

Commercial fishing for flatfish constitutes a major component of global capture fisheries, primarily targeting bottom-dwelling species in temperate and subarctic waters. Key species include the Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus), prized for its large size and high value, and the Pacific Dover sole (Microstomus pacificus), which dominates catches in the northeastern Pacific due to its abundance and adaptability to deep-water habitats. These species, along with others like plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) and flounders, support targeted fisheries that emphasize sustainable quotas to prevent overexploitation.[50][105] Global annual catches of flatfish have stabilized at approximately 500,000 tonnes in the 2020s, a notable decline from peaks exceeding 800,000 tonnes in the 1980s, as reported in FAO capture production statistics. This reduction reflects intensified fishing pressure during earlier decades, coupled with regulatory measures like total allowable catches (TACs) implemented in regions such as the North Atlantic and northeast Pacific to rebuild stocks. For instance, Atlantic halibut landings have fluctuated but remained below historical highs, while Pacific Dover sole catches have shown relative stability due to effective management under frameworks like the U.S. Pacific Fishery Management Council.[106][50] The predominant fishing methods are bottom trawling, utilizing otter trawls or Danish seine nets to sweep the seafloor where flatfish reside, and longlining, which deploys baited hooks along the bottom for selective capture of larger individuals like halibut. Otter trawls, dragged by vessels at depths up to 1,000 meters, account for the majority of landings but generate significant bycatch, including juvenile flatfish that escape through mesh but suffer high mortality from stress and injury. Danish seine methods reduce bottom impact compared to otter trawls by using weighted ropes to herd fish, while longlines minimize habitat disturbance but can incidentally hook seabirds or non-target fish. Efforts to mitigate bycatch of juveniles include modified gear with larger mesh panels and escape vents, which have proven effective in reducing discard rates by up to 50% in some trials.[107] Economically, the flatfish sector generates an estimated $2-3 billion in annual value through landings and exports, driven by demand for fresh, frozen, and processed products in international markets. Top exporting nations include Norway, which leads in European flatfish like plaice and turbot with exports valued at over $500 million yearly; the United States, contributing through Pacific species such as Dover sole with landings exceeding 3,000 tonnes annually; and China, a major processor and re-exporter of imported flatfish, bolstering global supply chains. Aquaculture provides a supplementary source to wild catches, helping stabilize market availability amid fluctuating natural stocks.[105]Aquaculture Practices

Aquaculture of flatfish primarily focuses on high-value species such as turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) and various flounders, including olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) and summer flounder (P. dentatus). These species are favored for their rapid growth potential and market demand, with turbot being a cornerstone in European operations and olive flounder dominant in Asian production. Global farmed flatfish production has stabilized at approximately 180,000 tonnes annually in the 2020s, representing a modest share of overall marine finfish aquaculture but significant for premium markets. China leads as the largest producer, accounting for over 50% of output through intensive farming, followed by European nations like Spain and France, where production exceeds 10,000 tonnes combined yearly.[108][109] Farming systems for flatfish emphasize controlled environments to address their unique larval development. Larvae are hatched and reared in land-based recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), which recycle water to maintain optimal salinity, temperature, and oxygen levels, minimizing environmental impacts and disease risks during the sensitive early stages. Juveniles undergo weaning from live feeds, such as rotifers and Artemia nauplii, to formulated microdiets enriched with lipids and proteins, typically achieving this transition by 20-30 days post-hatch to support metamorphosis. Grow-out phases shift to sea cages in coastal waters for species like turbot, allowing natural water exchange and faster growth to market size (1-2 kg) in 12-18 months, or continue in onshore RAS for higher biosecurity in regions with stricter regulations.[110][111][112] Key challenges in flatfish aquaculture include high mortality rates during metamorphosis, often exceeding 40% due to physiological stress and incomplete eye migration, which demands precise environmental management like stable temperatures around 18-20°C. Cannibalism emerges as a major post-settlement issue, particularly in flounders, where size disparities lead to losses of 20-30% without regular grading to separate cohorts. To counter these, selective breeding programs have been implemented, yielding genetic lines with up to 30% faster growth rates through mass selection for body weight and survival traits, as seen in improved olive flounder strains. Aquaculture expansion has partially offset declines in wild flatfish populations from overfishing, providing a sustainable alternative supply.[113][114][115][116]Culinary and Cultural Uses

Flatfish are prized in culinary applications for their mild, delicate flavor and firm, flaky texture, which make them versatile for various cooking methods. Species such as sole and flounder are often prepared by filleting techniques like butterflying, where the fish is split open along the top edge to remove the backbone while keeping the fillets attached for even cooking, resulting in a single, bone-free piece ideal for grilling or baking.[117] Grilling and baking are common methods, particularly for halibut, where the fillets are seasoned simply and cooked to an internal temperature of around 130°F to maintain their firmness without drying out.[118] In Nordic cuisines, smoked halibut is a traditional preparation, involving brining and slow-smoking the fillets to achieve a tender, flavorful result that enhances its subtle taste.[119] Nutritionally, flatfish offer a high-protein profile with approximately 16-19 grams of protein per 100 grams, alongside low calorie content around 70-90 calories per 100 grams, making them a lean dietary choice. They provide omega-3 fatty acids at levels of about 0.3-0.5 grams per 100 grams, including EPA and DHA, which support heart health. Compared to larger predatory fish like tuna, flatfish such as flounder and sole have notably low mercury concentrations, typically below 0.1 parts per million, allowing for safer frequent consumption.[120][121][122] Culturally, flatfish have held significance in historical trade and modern cuisine. In medieval Europe, plaice emerged as the most popular flatfish based on archaeological evidence from fishbone remains across sites in the southern North Sea region, indicating widespread consumption and trade as a staple protein source during that era. In contemporary Japanese culture, hirame (olive flounder) is a revered white-fleshed fish in sushi and sashimi, valued for its elegant umami and seasonal availability from winter to spring, often featured in premium Edomae-style preparations that highlight its cultural role in high-end dining.[123][124]Conservation and Threats

Flatfish populations vary widely in conservation status, with many species considered stable but others facing significant risks due to overexploitation and environmental pressures. According to assessments by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), several flatfish species are listed as vulnerable or higher, including the Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus), classified as Near Threatened due to historical overfishing and slow recovery rates.[125] Similarly, the windowpane flounder (Scophthalmus aquosus) is assessed as Least Concern, though it faces pressures from bycatch in trawl fisheries and habitat degradation. While exact global percentages are challenging to pinpoint due to incomplete assessments for all ~800 flatfish species, European marine fish evaluations indicate that approximately 6% of assessed Pleuronectiformes (flatfish order) are threatened (midpoint estimate), highlighting bycatch and habitat loss as key drivers.[126][127] In the U.S., the summer flounder (Paralichthys dentatus) stock is not overfished as of the 2025 assessment, though it remains subject to ongoing monitoring for overfishing risks.[128] Major threats to flatfish include bycatch in non-selective fishing gear, habitat loss in coastal and estuarine nurseries, pollution, and climate change. Bycatch is a primary concern in beam trawl fisheries targeting flatfish like plaice and sole, where non-target species such as cod are incidentally captured, exacerbating population declines.[129] Habitat degradation, particularly in estuaries critical for juvenile flatfish development, stems from coastal development, dredging, and sedimentation, reducing available nursery grounds by up to 50% in some regions.[130] Pollution from agricultural runoff and industrial effluents introduces contaminants like heavy metals and nutrients into estuarine systems, impairing flatfish growth and survival; for instance, elevated nutrient levels lead to hypoxic zones that stress benthic species.[131] Climate change compounds these issues by warming waters and altering distributions, with models projecting poleward range shifts of 100-200 km for many flatfish species by the 2050s, potentially disrupting fisheries and exposing populations to new vulnerabilities like ocean acidification.[132] Conservation efforts focus on sustainable management through quotas, protected areas, and habitat restoration, yielding notable recoveries in some stocks. In the European Union, total allowable catches (TACs) under the Common Fisheries Policy regulate harvests of key flatfish like North Sea plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) and sole (Solea solea), with quotas set based on scientific advice to maintain stocks above maximum sustainable yield levels; for example, 2020 TACs for these species were increased due to strong recruitment signals.[133][134] Marine protected areas (MPAs) play a vital role by safeguarding benthic habitats and reducing bycatch, with studies showing enhanced flatfish biomass in protected zones compared to fished areas.[135] In the U.S. Northeast, post-1990s reforms under the Magnuson-Stevens Act, including strict quotas and seasonal closures, have led to recoveries in groundfish stocks, including yellowtail flounder and summer flounder, where commercial revenues rose over 60% since 2000 following population rebounds.[136][137] These measures demonstrate that targeted interventions can reverse declines, though ongoing climate adaptation is essential for long-term viability.References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Pleuronectiformes

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/225866979_Flatfish_Pleuronectiformes_chromatic_biology