Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heterosexuality

View on Wikipedia

| Sexual orientation |

|---|

|

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to people of the opposite sex. It "also refers to a person's sense of identity based on those attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions."[1][2] Someone who is heterosexual is commonly referred to as straight.

Along with bisexuality and homosexuality, heterosexuality is one of the three main categories of sexual orientation within the heterosexual–homosexual continuum.[1] Across cultures, most people are heterosexual, and heterosexual activity is by far the most common type of sexual activity.[3][4] Heterosexuality has mostly been viewed as the normative and most socially dominant form of sexual orientation.[5][6]

Scientists do not know the exact cause of sexual orientation, but they theorize that it is caused by a complex interplay of genetic, hormonal, and environmental influences,[7][8][9] and do not view it as a choice.[7][8][10] Although no single theory on the cause of sexual orientation has yet gained widespread support, scientists favor biologically based theories.[7] There is considerably more evidence supporting nonsocial, biological causes of sexual orientation than social ones, especially for males.[3][11][12]

The term heterosexual or heterosexuality is usually applied to humans, but heterosexual behavior is observed in all other mammals and in other animals, as it is necessary for sexual reproduction.

Terminology

[edit]Hetero- comes from the Greek word ἕτερος [héteros], meaning "other party" or "another",[13] used in science as a prefix meaning "different";[14] and the Latin word for sex (that is, characteristic sex or sexual differentiation).

The current use of the term heterosexual has its roots in the broader 19th century tradition of personality taxonomy. The term heterosexual was coined alongside the word homosexual by Karl Maria Kertbeny in 1869.[15] The terms were not in current use during the late nineteenth century, but were reintroduced by Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Albert Moll around 1890.[15] The noun came into wider use from the early 1920s, but did not enter common use until the 1960s. The colloquial shortening "hetero" is attested from 1933. The abstract noun "heterosexuality" is first recorded in 1900.[16] The word "heterosexual" was listed in Merriam-Webster's New International Dictionary in 1923 as a medical term for "morbid sexual passion for one of the opposite sex"; however, in 1934 in their Second Edition Unabridged it is defined as a "manifestation of sexual passion for one of the opposite sex; normal sexuality".[17]

Hyponyms of heterosexual include heteroflexible.[18][19]

The word can be informally[14] shortened to "hetero".[20] The term straight originated as a mid-20th century gay slang term for heterosexuals, ultimately coming from the phrase "to go straight" (as in "straight and narrow"), or stop engaging in homosexual sex. One of the first uses of the word in this way was in 1941 by author G. W. Henry.[21] Henry's book concerned conversations with homosexual males and used this term in connection with people who are identified as ex-gays. It is now simply a colloquial term for "heterosexual", having changed in primary meaning over time. Some object to usage of the term straight because it implies that non-heterosexual people are crooked.[22]

Demographics

[edit]

In their 2016 literature review, Bailey et al. stated that they "expect that in all cultures the vast majority of individuals are sexually predisposed exclusively to the other sex (i.e., heterosexual)" and that there is no persuasive evidence that the demographics of sexual orientation have varied much across time or place.[3] Heterosexual activity between only one male and one female is by far the most common type of sociosexual activity.[4]

According to several major studies, 89% to 98% of people have had only heterosexual contact within their lifetime;[23][24][25][26] but this percentage falls to 79–84% when either or both same-sex attraction and behavior are reported.[26]

A 1992 study reported that 93.9% of males in Britain have only had heterosexual experience, while in France the number was reported at 95.9%.[27] According to a 2008 poll, 85% of Britons have only opposite-sex sexual contact while 94% of Britons identify themselves as heterosexual.[28] Similarly, a survey by the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) in 2010 found that 95% of Britons identified as heterosexual, 1.5% of Britons identified themselves as homosexual or bisexual, and the last 3.5% gave more vague answers such as "don't know", "other", or did not respond to the question.[29][30] In the United States, according to a Williams Institute report in April 2011, 96% or approximately 250 million of the adult population are heterosexual.[31]

An October 2012 Gallup poll provided unprecedented demographic information about those who identify as heterosexual, arriving at the conclusion that 96.6%, with a margin of error of ±1%, of all U.S. adults identify as heterosexual.[32] The Gallup results show:

| Age/Gender | Heterosexual | Non-heterosexual | Don't know/Refused |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–29 | 90.1% | 6.4% | 3.5% |

| 30–49 | 93.6% | 3.2% | 3.2% |

| 50–64 | 93.1% | 2.6% | 4.3% |

| 65+ | 91.5% | 1.9% | 6.5% |

| 18–29, Women | 88.0% | 8.3% | 3.8% |

| 18–29, Men | 92.1% | 4.6% | 3.3% |

In a 2015 YouGov survey of 1,000 adults of the United States, 89% of the sample identified as heterosexual, 4% as homosexual (2% as homosexual male and 2% as homosexual female) and 4% as bisexual (of either sex).[33]

Bailey et al., in their 2016 review, stated that in recent Western surveys, about 93% of men and 87% of women identify as completely heterosexual, and about 4% of men and 10% of women as mostly heterosexual.[3]

Academic study

[edit]Biological and environmental

[edit]No simple and singular determinant for sexual orientation has been conclusively demonstrated, but scientists believe that a combination of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors determine sexual orientation.[7][8][9] They favor biological theories for explaining the causes of sexual orientation,[3][7] as there is considerably more evidence supporting nonsocial, biological causes than social ones, especially for males.[3][11][12]

Factors related to the development of a heterosexual orientation include genes, prenatal hormones, and brain structure, and their interaction with the environment.

Prenatal hormones

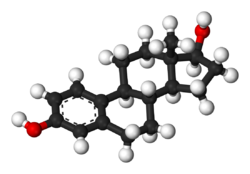

[edit]The neurobiology of the masculinization of the brain is fairly well understood. Estradiol and testosterone, which is catalyzed by the enzyme 5α-reductase into dihydrotestosterone, act upon androgen receptors in the brain to masculinize it. If there are few androgen receptors (people with androgen insensitivity syndrome) or too much androgen (females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia), there can be physical and psychological effects.[35] It has been suggested that both male and female heterosexuality are the results of this process.[36] In these studies heterosexuality in females is linked to a lower amount of masculinization than is found in lesbian females, though when dealing with male heterosexuality there are results supporting both higher and lower degrees of masculinization than homosexual males.

Animals and reproduction

[edit]Sexual reproduction in the animal world is facilitated through opposite-sex sexual activity, although there are also animals that reproduce asexually, including protozoa and lower invertebrates.[37]

Reproductive sex does not require a heterosexual orientation, since sexual orientation typically refers to a long-term enduring pattern of sexual and emotional attraction leading often to long-term social bonding, while reproduction requires as little as a single act of copulation to fertilize the ovum by sperm.[38][39][40]

Sexual fluidity

[edit]Often, sexual orientation and sexual orientation identity are not distinguished, which can impact accurately assessing sexual identity and whether or not sexual orientation is able to change; sexual orientation identity can change throughout an individual's life, and may or may not align with biological sex, sexual behavior or actual sexual orientation.[41][42][43] Sexual orientation is stable and unlikely to change for the vast majority of people, but some research indicates that some people may experience change in their sexual orientation, and this is more likely for women than for men.[44] The American Psychological Association distinguishes between sexual orientation (an innate attraction) and sexual orientation identity (which may change at any point in a person's life).[45]

A 2012 study found that 2% of a sample of 2,560 adult participants reported a change of sexual orientation identity after a 10-year period. For men, a change occurred in 0.78% of those who had identified as heterosexual, 9.52% of homosexuals, and 47% of bisexuals. For women, a change occurred in 1.36% of heterosexuals, 63.6% of lesbians, and 64.7% of bisexuals.[46]

Heteroflexibility is a form of sexual orientation or situational sexual behavior characterized by minimal homosexual activity in an otherwise primarily heterosexual orientation that is considered to distinguish it from bisexuality. It has been characterized as "mostly straight".[47]

Identity vs behavior

[edit]Some researchers observe that behavior and identity sometimes do not match: for instance, some women identify as simultaneously heterosexual and bisexual.[48] Self-identified straight women may have sex with women[49]: 22 [50] or self-identified straight men may have sex with men.[51]

Sexual orientation change efforts

[edit]Sexual orientation change efforts are methods that aim to change sexual orientation, used to try to convert homosexual and bisexual people to heterosexuality. Scientists and mental health professionals generally do not believe that sexual orientation is a choice.[7][10] There are no studies of adequate scientific rigor that conclude that sexual orientation change efforts are effective.[52]

Society and culture

[edit]

A heterosexual couple, a man and woman in an intimate relationship, form the core of a nuclear family.[53] Many societies throughout history have insisted that a marriage take place before the couple settle down, but enforcement of this rule or compliance with it has varied considerably.

Symbolism

[edit]Heterosexual symbolism dates back to the earliest artifacts of humanity, with gender symbols, ritual fertility carvings, and primitive art. This was later expressed in the symbolism of fertility rites and polytheistic worship, which often included images of human reproductive organs, such as lingam in Hinduism. Modern symbols of heterosexuality in societies derived from European traditions still reference symbols used in these ancient beliefs. One such image is a combination of the symbol for Mars, the Roman god of war, as the definitive male symbol of masculinity, and Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty, as the definitive female symbol of femininity. The unicode character for this combined symbol is ⚤ (U+26A4).

Historical views

[edit]There was no need to coin a term such as heterosexual until terms emerged with which it could be compared and contrasted. Jonathan Ned Katz dates the definition of heterosexuality, as it is used today, to the late 19th century.[54] According to Katz, in the Victorian era, sex was seen as a means to achieve reproduction, and relations between the sexes were not believed to be overtly sexual. The body was thought of as a tool for procreation – "Human energy, thought of as a closed and severely limited system, was to be used in producing children and in work, not wasted in libidinous pleasures."[54]

Katz argues that modern ideas of sexuality and eroticism began to develop in America and Germany in the later 19th century. The changing economy and the "transformation of the family from producer to consumer"[54] resulted in shifting values. The Victorian work ethic had changed, pleasure became more highly valued and this allowed ideas of human sexuality to change. Consumer culture had created a market for the erotic, pleasure became commoditized. At the same time medical doctors began to acquire more power and influence. They developed the medical model of "normal love", in which healthy men and women enjoyed sex as part of a "new ideal of male-female relationships that included.. an essential, necessary, normal eroticism."[54] This model also had a counterpart, "the Victorian Sex Pervert", anyone who failed to meet the norm. The basic oppositeness of the sexes was the basis for normal, healthy sexual attraction. "The attention paid the sexual abnormal created a need to name the sexual normal, the better to distinguish the average him and her from the deviant it."[54] The creation of the term heterosexual consolidated the social existence of the pre-existing heterosexual experience and created a sense of ensured and validated normalcy within it.

Religious views

[edit]The Judeo-Christian tradition has several scriptures related to heterosexuality. The Book of Genesis states that God created women because "It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him,",[55] and that "Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh"[56]

For the most part, religious traditions in the world reserve marriage to heterosexual unions, but there are exceptions including certain Buddhist and Hindu traditions, Unitarian Universalists, Metropolitan Community Church, some Anglican dioceses, and some Quaker, United Church of Canada, and Reform and Conservative Jewish congregations.[57][58]

Almost all religions believe that sex between a man and a woman within marriage is allowed, but there are a few that believe that it is a sin, such as The Shakers, The Harmony Society, and The Ephrata Cloister. These religions tend to view all sexual relations as sinful, and promote celibacy. Some religions require celibacy for certain roles, such as Catholic priests; however, the Catholic Church also views heterosexual marriage as sacred and necessary.[59]

Heteronormativity and heterosexism

[edit]

Heteronormativity denotes or relates to a world view that promotes heterosexuality as the normal or preferred sexual orientation for people to have. It can assign strict gender roles to males and females. The term was popularized by Michael Warner in 1991.[60] Feminist Adrienne Rich argues that compulsory heterosexuality, a continual and repeating reassertion of heterosexual norms, is a facet of heterosexism.[61] Compulsory heterosexuality is the idea that female heterosexuality is both assumed and enforced by a patriarchal society. Heterosexuality is then viewed as the natural inclination or obligation by both sexes. Consequently, anyone who differs from the normalcy of heterosexuality is deemed deviant or abhorrent.[62]

Heterosexism is a form of bias or discrimination in favor of opposite-sex sexuality and relationships. It may include an assumption that everyone is heterosexual and may involve various kinds of discrimination against gays, lesbians, bisexuals, asexuals, heteroflexible people, or transgender or non-binary individuals.

Straight pride is a slogan that arose in the late 1980s and early 1990s and has been used primarily by social conservative groups as a political stance and strategy.[63] The term is described as a response to gay pride[64][65][66] adopted by various LGBTQ groups in the early 1970s or to the accommodations provided to gay pride initiatives.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Sexual orientation, homosexuality and bisexuality". American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on August 8, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "APA California Amicus Brief" (PDF). Courtinfo.ca.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

- ^ a b c d e f Bailey, J. Michael; Vasey, Paul; Diamond, Lisa; Breedlove, S. Marc; Vilain, Eric; Epprecht, Marc (2016). "Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 17 (2): 45–101. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616. PMID 27113562.

- ^ a b "Human sexual activity – Sociosexual activity". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ^ "The invention of 'heterosexuality'". www.bbc.com. 2017-03-16. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Fischer, Nancy L. (2013). "SEEING "STRAIGHT," Contemporary Critical Heterosexuality Studies and Sociology: An Introduction". The Sociological Quarterly. 54 (4): 501–510. doi:10.1111/tsq.12040. ISSN 0038-0253. JSTOR 24581871.

- ^ a b c d e f Frankowski BL; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence (June 2004). "Sexual orientation and adolescents". Pediatrics. 113 (6): 1827–32. doi:10.1542/peds.113.6.1827. PMID 15173519.

- ^ a b c Lamanna, Mary Ann; Riedmann, Agnes; Stewart, Susan D (2014). Marriages, Families, and Relationships: Making Choices in a Diverse Society. Cengage Learning. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-305-17689-8. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

The reason some individuals develop a gay sexual identity has not been definitively established – nor do we yet understand the development of heterosexuality. The American Psychological Association (APA) takes the position that a variety of factors impact a person's sexuality. The most recent literature from the APA says that sexual orientation is not a choice that can be changed at will, and that sexual orientation is most likely the result of a complex interaction of environmental, cognitive and biological factors...is shaped at an early age...[and evidence suggests] biological, including genetic or inborn hormonal factors, play a significant role in a person's sexuality (American Psychological Association 2010).

- ^ a b Gail Wiscarz Stuart (2014). Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Nursing. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 502. ISBN 978-0-323-29412-6. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

No conclusive evidence supports any one specific cause of homosexuality; however, most researchers agree that biological and social factors influence the development of sexual orientation.

- ^ a b Gloria Kersey-Matusiak (2012). Delivering Culturally Competent Nursing Care. Springer Publishing Company. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8261-9381-0. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

Most health and mental health organizations do not view sexual orientation as a 'choice.'

- ^ a b LeVay, Simon (2017). Gay, Straight, and the Reason Why: The Science of Sexual Orientation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199752966.

- ^ a b Balthazart, Jacques (2012). The Biology of Homosexuality. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199838820.

- ^ Klein, Ernest, A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language: dealing with the origin of words and their sense development thus illustrating the history of civilization and culture, p. 345. Oxford: Elsevier, 2000

- ^ a b "Hetero | Define Hetero at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- ^ a b Oosterhuis, Harry (1 June 2012). "Sexual Modernity in the Works of Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Albert Moll". Medical History. 56 (2): 133–155. doi:10.1017/mdh.2011.30. PMC 3381524. PMID 23002290.

- ^ Mills, Jonathan, Love, Covenant & Meaning, p. 22, Regent College Publishing, 1997.

- ^ Katz, Jonathan Ned (1995) The Invention of Heterosexuality, p. 92. New York, NY: Dutton (Penguin Books). ISBN 0-525-93845-1

- ^ Porn.com: Making Sense of Online Pornography - Page 229, Feona Attwood - 2010

- ^ Patience: A Gay Man's Virtue - Page 80, La Lumiere - 2012

- ^ "hetero". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

- ^ Henry, G. W. (1941). Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns. New York: Paul B. Hoeber

- ^ Encyclopedia Of School Psychology - Page 298, T. Steuart Watson, Christopher H. Skinner - 2004

- ^ Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226469573.[page needed]

- ^ Wellings, K., Field, J., Johnson, A., & Wadsworth, J. (1994). Sexual behavior in Britain: The national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles. London, UK: Penguin Books.[page needed]

- ^ Bogaert AF (September 2004). "The prevalence of male homosexuality: the effect of fraternal birth order and variations in family size". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 230 (1): 33–7. Bibcode:2004JThBi.230...33B. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.04.035. PMID 15275997. Bogaert argues that: "The prevalence of male homosexuality is debated. One widely reported early estimate was 10% (e.g., Marmor, 1980; Voeller, 1990). Some recent data provided support for this estimate (Bagley and Tremblay, 1998), but most recent large national samples suggest that the prevalence of male homosexuality in modern western societies, including the United States, is lower than this early estimate (e.g., 1–2% in Billy et al., 1993; 2–3% in Laumann et al., 1994; 6% in Sell et al., 1995; 1–3% in Wellings et al., 1994). It is of note, however, that homosexuality is defined in different ways in these studies. For example, some use same-sex behavior and not same-sex attraction as the operational definition of homosexuality (e.g., Billy et al., 1993); many sex researchers (e.g., Bailey et al., 2000; Bogaert, 2003; Money, 1988; Zucker and Bradley, 1995) now emphasize attraction over overt behavior in conceptualizing sexual orientation." (p. 33) Also: "...the prevalence of male homosexuality (in particular, same-sex attraction) varies over time and across societies (and hence is a "moving target") in part because of two effects: (1) variations in fertility rate or family size; and (2) the fraternal birth order effect. Thus, even if accurately measured in one country at one time, the rate of male homosexuality is subject to change and is not generalizable over time or across societies." (p. 33)

- ^ a b Hope, Debra A, ed. (2009). Contemporary Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identities. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Vol. 54. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-09556-1. ISBN 978-0-387-09555-4.

- ^ "Sexual Behavior Levels Compared in Studies In Britain and France". The New York Times. 8 December 1992.

- ^ "Sex uncovered poll: Homosexuality". Guardian. London. 26 October 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Harford, Tim (1 October 2010). "More or Less examines Office for National Statistics figures on gay, lesbian and bisexual people". BBC.

- ^ "Measuring Sexual Identity : Evaluation Report, 2010". Office for National Statistics. 23 September 2010.

- ^ Gary Gates (April 2011). "How Many People are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender?". The Williams Institute. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2014.Gary Gates (April 2011). "How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender?" (PDF). The Williams Institute. p. 1.

- ^ Gates, Gary J.; Newport, Frank (2012-10-18). "Special Report: 3.4% of U.S. Adults Identify as LGBT". Gallup. Retrieved 2015-01-13.

- ^ Yougov report (PDF) (Report). Yougov. 21 August 2015.

- ^ PDB: 2AM9; Pereira de Jésus-Tran K, Côté PL, Cantin L, Blanchet J, Labrie F, Breton R (May 2006). "Comparison of crystal structures of human androgen receptor ligand-binding domain complexed with various agonists reveals molecular determinants responsible for binding affinity". Protein Sci. 15 (5): 987–99. doi:10.1110/ps.051905906. PMC 2242507. PMID 16641486.

- ^ Vilain, E. (2000). Genetics of Sexual Development. Annual Review of Sex Research, 11:1–25

- ^ Wilson, G. and Rahman, Q., (2005). Born Gay. Chapter 5. London: Peter Owen Publishers

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia (Colum. Univ. Press, 5th ed. [casebound?] 1993 (ISBN 0-395-62438-X)), entry Reproduction.

- ^ "Go Ask Alice!: Pregnant without intercourse?". Archived from the original on December 22, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ "Can Pregnancy Occur | Pregnancy Myths on How Pregnancy Occurs". Americanpregnancy.org. 2012-04-24. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- ^ Lawyers Guide to Forensic Medicine SBN 978-1-85941-159-9 By Bernard Knight - Page 188 "Pregnancy is well known to occur from such external ejaculation ..."

- ^ Sinclair, Karen, About Whoever: The Social Imprint on Identity and Orientation, NY, 2013 ISBN 9780981450513

- ^ Rosario, M.; Schrimshaw, E.; Hunter, J.; Braun, L. (2006). "Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time". Journal of Sex Research. 43 (1): 46–58. doi:10.1080/00224490609552298. PMC 3215279. PMID 16817067.

- ^ Ross, Michael W.; Essien, E. James; Williams, Mark L.; Fernandez-Esquer, Maria Eugenia. (2003). "Concordance Between Sexual Behavior and Sexual Identity in Street Outreach Samples of Four Racial/Ethnic Groups". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 30 (2). American Sexually Transmitted Diseases Association: 110–113. doi:10.1097/00007435-200302000-00003. PMID 12567166. S2CID 21881268.

- ^

- Bailey, J. Michael; Vasey, Paul; Diamond, Lisa; Breedlove, S. Marc; Vilain, Eric; Epprecht, Marc (2016). "Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 17 (2): 45–101. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616. PMID 27113562.

Sexual fluidity is situation-dependent flexibility in a person's sexual responsiveness, which makes it possible for some individuals to experience desires for either men or women under certain circumstances regardless of their overall sexual orientation....We expect that in all cultures the vast majority of individuals are sexually predisposed exclusively to the other sex (i.e., heterosexual) and that only a minority of individuals are sexually predisposed (whether exclusively or non-exclusively) to the same sex.

- Coon, Dennis; Mitterer, John O. (2012). Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior with Concept Maps and Reviews. Cengage Learning. p. 372. ISBN 978-1111833633. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

Sexual orientation is a deep part of personal identity and is usually quite stable. Starting with their earliest erotic feelings, most people remember being attracted to either the opposite sex or the same sex. [...] The fact that sexual orientation is usually quite stable doesn't rule out the possibility that for some people sexual behavior may change during the course of a lifetime.

- Anderson, Eric; McCormack, Mark (2016). "Measuring and Surveying Bisexuality". The Changing Dynamics of Bisexual Men's Lives. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 47. ISBN 978-3-319-29412-4. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

[R]esearch suggests that women's sexual orientation is slightly more likely to change than men's (Baumeister 2000; Kinnish et al. 2005). The notion that sexual orientation can change over time is known as sexual fluidity. Even if sexual fluidity exists for some women, it does not mean that the majority of women will change sexual orientations as they age – rather, sexuality is stable over time for the majority of people.

- Bailey, J. Michael; Vasey, Paul; Diamond, Lisa; Breedlove, S. Marc; Vilain, Eric; Epprecht, Marc (2016). "Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 17 (2): 45–101. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616. PMID 27113562.

- ^ "Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation" (PDF). American Psychological Association. 2009. pp. 63, 86. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Mock, S. E.; Eibach, R. P. (2012). "Stability and change in sexual orientation identity over a 10-year period in adulthood" (PDF). Archives of Sexual Behavior. 41 (3): 641–648. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9761-1. PMID 21584828. S2CID 15771368.

- ^ Thompson, E.M.; Morgan, E.M. (2008). ""Mostly straight" young women: Variations in sexual behavior and identity development". Developmental Psychology. 44 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.15. PMID 18194001.

- ^ Rust, Paula C. (2000-07-12). "Two Many and Not Enough: The Meanings of Bisexual Identities". Journal of Bisexuality. 1 (1): 39. doi:10.1300/J159v01n01_04. ISSN 1529-9716.

Sixteen percent [of 917 multisexual respondents] have compound identities consisting of the term bisexual prefaced with same-gender monosexual modifiers or vice versa, for example, "lesbian-identified bisexual," "bisexual lesbian," or "gay bisexual," and ten percent use the compound identity "heterosexual-identified bisexual".

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Solarz1999was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lisa M. Diamond (2009). Sexual Fluidity. Harvard University Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0674033696. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Singal (14 February 2017). "How Straight Men Explain Their Same-Sex Encounters". Retrieved 5 July 2025.

- ^ American Psychological Association: Resolution on Appropriate Affirmative Responses to Sexual Orientation Distress and Change Efforts

- ^ "... the core of a family is a heterosexual couple who have children who they raise to adulthood - the so-called nuclear family." Encyclopedia of family health

- ^ a b c d e Katz, Jonathan Ned (January–March 1990). "The Invention of Heterosexuality" (PDF). Socialist Review (20): 7–34. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Bible, Genesis 2:18 (KJV)

- ^ Bible, Genesis 2:24 (KJV)

- ^ "World Religions and Same Sex Marriage" (PDF). Columbus School of Law. 20 June 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Affirming Congregations and Ministries of the United Church of Canada Archived February 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [1] Archived February 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Warner, Michael (1991), "Introduction: Fear of a Queer Planet". Social Text; 9 (4 [29]): 3–17

- ^ Rich, Adrienne (1980), "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence". "Signs"; Pages 631-660.

- ^ Rich, Adrienne (1980). Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence. Onlywomen Press Ltd. p. 32. ISBN 0-906500-07-9.

- ^ "Making colleges and universities safe for gay and lesbian students: Report and recommendations of the Governor's Commission on Gay and Lesbian Youth" (PDF). Massachusetts. Governor's Commission on Gay and Lesbian Youth., p.20. "A relatively recent tactic used in the backlash opposing les/bi/gay/trans campus visibility is the so-called "heterosexual pride" strategy".

- ^ Eliason, Michele J.; Schope, Robert (2007). "Shifting Sands or Solid Foundation? Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Identity Formation". In Meyer, Ilan H.; Northridge, Mary E. (eds.). The Health of Sexual Minorities. pp. 3–26. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-31334-4_1. ISBN 978-0-387-28871-0. "Not surprisingly, individuals in the pride stage are most criticized not only by heterosexual persons but also many LGBT individuals, who are uncomfortable forcing the majority to share the discomfort. Heterosexual individuals may express bewilderment at the term "gay pride", arguing that they do not talk about "straight pride"".

- ^ Eliason, Michele J. Who cares?: institutional barriers to health care for lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons, p.55 (1996)

- ^ Zorn, Eric (November 14, 2010). "When pride turns shameful". Chicago Tribune.

Further reading

[edit]- LeVay, Simon. Gay, Straight, and the Reason Why: The Science of Sexual Orientation, Oxford University Press, 2017

- Johnson, P. (2005) Love, Heterosexuality and Society. London: Routledge

- Answers to Your Questions About Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality. American Psychiatric Association.

- Bohan, Janis S., Psychology and Sexual Orientation: Coming to Terms, Routledge, 1996 ISBN 0-415-91514-7

- Kinsey, Alfred C., et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33412-8

- Kinsey, Alfred C., et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33411-X

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Heterosexuality at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Heterosexuality at Wikiquote Media related to Heterosexuality at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Heterosexuality at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of heterosexuality at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of heterosexuality at Wiktionary- Keel, Robert O., Heterosexual Deviance. (Goode, 1994, chapter 8, and Chapter 9, 6th edition, 2001.) Sociology of Deviant Behavior: FS 2003, University of Missouri–St. Louis.

- Coleman, Thomas F., What's Wrong with Excluding Heterosexual Couples from Domestic Partner Benefits Programs? Archived 2022-06-01 at the Wayback Machine Unmarried America, American Association for Single People.

Heterosexuality

View on GrokipediaHeterosexuality is a sexual orientation defined by predominant emotional, romantic, and sexual attraction to individuals of the opposite biological sex.[1][2]

It constitutes the modal human sexual orientation, with population-based surveys consistently estimating that 85-95% of adults self-identify as heterosexual, varying modestly by region and methodology.[3][4][5]

Biologically, heterosexuality aligns with evolutionary imperatives for sexual reproduction between dimorphic sexes, shaped by a confluence of genetic predispositions, prenatal hormonal exposures, and neurodevelopmental processes that favor cross-sex attraction as the default outcome.[6][7][8]

This orientation underpins the propagation of species through complementary gamete production and has manifested stably across human populations and historical epochs, though contemporary academic discourse, often influenced by ideological biases, has scrutinized its normativity—including proposals, particularly in gender studies, to define heterosexuality based on self-identified gender rather than biological sex, which would classify certain biologically same-sex relationships as heterosexual if one partner identifies with the opposite gender— in favor of spectrum models despite limited empirical support for widespread fluidity in the majority. However, this conflicts with the specificity of the sex-based definition of the term, rendering gender identity irrelevant to its meaning.[9][6][10]

Definition and Terminology

Core Definition

Heterosexuality is a sexual orientation defined by persistent patterns of sexual, romantic, and emotional attraction to individuals of the opposite biological sex.[7][11] This attraction typically manifests as a preference for mating or partnering with the complementary sex—males toward females and vice versa—distinguishing it from same-sex or bisexual orientations.[2] In empirical terms, heterosexual orientation is assessed through self-reported attractions, physiological responses to opposite-sex stimuli, and behavioral patterns, with studies indicating it as the predominant orientation across human populations, reported by approximately 90-95% of individuals in large-scale surveys.[12] Biologically grounded, heterosexuality aligns with the dimorphic sex differences evolved for reproduction, where male gametes (sperm) and female gametes (ova) require cross-sex union for fertilization, driving selection pressures favoring opposite-sex attraction as the default mechanism for gene propagation.[7] Unlike behaviors that can be situational or volitional, core heterosexual orientation emerges early in development, often by adolescence, and shows high stability over time, with longitudinal data revealing minimal shifts (less than 2% conversion rates) in self-identified heterosexual adults.[8] This stability underscores its distinction from transient preferences or cultural influences, rooted instead in innate predispositions shaped by genetic and prenatal factors.[13]Etymology and Usage Evolution

The term "heterosexual" was first coined in 1869 by Austro-Hungarian journalist Karl-Maria Kertbeny (born Károly Mária Benkő), who used the German "Heterosexuell" in an open letter advocating the decriminalization of same-sex relations under Prussian law.[14] [15] Kertbeny derived it from the Greek prefix hetero- ("other" or "different") combined with Latin sexus ("sex"), intending to denote sexual attraction toward persons of the opposite sex as a counterpart to "homosexual," which he also introduced, framing both as natural variations to argue against pathologizing or criminalizing non-procreative acts.[14] The noun form "heterosexuality" appeared shortly thereafter in German sexological contexts, with printed juxtapositions to homosexuality traceable to 1871.[16] The term entered English in 1892 through Charles Gilbert Chaddock's translation of Richard von Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis, where it described attraction to the opposite sex within a framework of sexual pathologies, often implying deviation from innate autoeroticism or procreative ideals prevalent in 19th-century psychiatry.[17] [18] Early dictionary definitions reflected this medical lens; for example, the 1923 Webster's entry labeled "heterosexuality" a condition of "morbid sexual passion for one of the opposite sex," aligning with views that non-reproductive desires—whether toward the same or opposite sex—warranted scrutiny as potential perversions.[18] By 1934, such pejorative qualifiers were removed in standard references, marking a shift toward viewing opposite-sex attraction as a baseline norm rather than an aberration.[18] Usage evolved further in the mid-20th century amid empirical studies of sexual behavior. Alfred Kinsey's 1948 Sexual Behavior in the Human Male and 1953 Sexual Behavior in the Human Female quantified heterosexual acts as predominant—reporting that 92% of men and 90% of women experienced primarily opposite-sex activity—reframing heterosexuality empirically as statistically modal without inherent morbidity.[18] Post-Kinsey, the term solidified in psychological and sociological discourse as denoting exclusive or predominant romantic and sexual orientation toward the opposite sex, distinct from behavior or identity labels. Colloquial synonyms like "straight" emerged in mid-20th-century American slang, initially denoting conformity to heterosexual norms ("going straight" from deviant paths), gaining traction in broader English by the 1960s.[19] In contemporary lexicon, "heterosexuality" consistently signifies biological sex-based attraction, with institutional sources like the American Psychological Association defining it since 1973 as "sexual orientation involving exclusive or predominant attraction to the opposite sex".[19] This stabilization contrasts with earlier fluidity, underscoring how categorical language influenced perceptions of sexual normality from advocacy tool to descriptive standard.Biological and Evolutionary Foundations

Evolutionary Adaptations and Reproductive Imperative

Sexual reproduction, which requires mating between individuals of opposite biological sexes, evolved in eukaryotes approximately 1-2 billion years ago, providing key advantages over asexual reproduction by generating genetic variation through recombination and independent assortment of chromosomes.[20] This process enhances adaptability to environmental changes and combats evolving parasites via the Red Queen hypothesis, where ongoing genetic shuffling maintains relative fitness against coevolving threats.[21] In dioecious species like humans, heterosexuality—as the orientation directing sexual attraction, arousal, and copulation toward the opposite sex—serves as the proximate mechanism ensuring gamete fusion between sperm and ova, without which sexual reproduction cannot occur.[22] Natural selection thus strongly favors heterosexual behaviors, as they directly maximize inclusive fitness by producing viable offspring capable of gene transmission.[22] Evolutionary adaptations supporting heterosexuality include morphological, physiological, and behavioral traits that facilitate opposite-sex mate recognition and union. In humans, pronounced sexual dimorphism—such as greater male upper-body strength (averaging 50-60% more than females) and female secondary sexual characteristics like wider hips for parturition—evolved to optimize reproductive roles, with males competing for access to fertile females and females selecting partners signaling genetic quality and provisioning ability.[23] Psychological adaptations, including universal preferences for facial symmetry, waist-to-hip ratios indicating fertility (0.7 in women), and cues of health, further align mating efforts with reproductive success; cross-cultural studies confirm these preferences predict higher offspring survival rates.[24] Hormonal mechanisms, such as testosterone-driven male libido and estrogen-modulated female ovulation cues, reinforce heterosexual pairing, as evidenced by increased intercourse frequency during fertile windows.[25] The reproductive imperative, an evolved motivational system, compels organisms to prioritize mating and parental investment to propagate genes, overriding short-term costs like energy expenditure or risk of injury.[26] In humans, this manifests as a high baseline sex drive—men averaging 2-3 times more frequent sexual thoughts than women, per self-reports and physiological measures—calibrated by ancestral selection pressures where heterosexual unions yielded 2-4 surviving offspring per individual under pre-modern mortality rates.[27] Failure to reproduce equates to zero fitness, rendering non-reproductive orientations evolutionarily disadvantageous unless offset by indirect benefits, though direct heterosexual reproduction remains the primary pathway; empirical models show that even slight reductions in lifetime mating opportunities (e.g., 10-20% via same-sex exclusivity) significantly lower expected descendant contributions.[28] These imperatives persist despite modern contraception, underscoring their deep evolutionary entrenchment.[29]Genetic, Hormonal, and Prenatal Mechanisms

Twin studies have demonstrated a heritable component to human sexual orientation, with concordance rates for monozygotic twins exceeding those for dizygotic twins, indicating genetic influences account for approximately 30-50% of the variance in male sexual orientation.[30][31] These findings suggest that genetic factors predispose the majority of individuals toward heterosexuality, the statistically predominant orientation, while specific polygenic variants contribute to non-heterosexual outcomes in a minority.[32] Genome-wide association studies have identified loci associated with same-sex behavior, implying that the absence or alternative configurations of such variants align with heterosexual development, though no single "heterosexual gene" exists and the trait is multifactorial.[33] Prenatal hormonal exposure, particularly androgens like testosterone, exerts organizational effects on brain development that underpin heterosexual orientation. In genetic males, typical surges of prenatal testosterone masculinize neural circuits, fostering attraction to females, whereas in genetic females, the relative absence of androgens permits feminized brain organization leading to attraction to males.[34][35] This organizational hypothesis is supported by evidence from conditions such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia, where females exposed to elevated prenatal androgens exhibit increased rates of bisexual or homosexual orientation, highlighting that standard low-androgen environments promote exclusive heterosexuality in females.[36] Additional prenatal mechanisms include the fraternal birth order effect, observed in males, wherein each additional older brother increases the odds of homosexuality by about 33% due to maternal immune responses targeting male-specific proteins, potentially altering fetal brain development.[37] Consequently, males without older brothers—or those unaffected by this immune hypothesis—follow the default prenatal trajectory toward heterosexual orientation.[38] Proxy markers like the 2D:4D digit ratio, reflective of prenatal androgen exposure, correlate with sexual orientation, with heterosexual males typically showing more masculinized (lower) ratios than homosexual males.[39] These prenatal factors collectively underscore heterosexuality as the normative outcome of undisturbed genetic and hormonal developmental processes.[40]Evidence from Non-Human Animals

In non-human animals, heterosexual mating constitutes the essential mechanism for sexual reproduction across gonochoristic species, which comprise the vast majority of animals. Gonochorism, characterized by distinct male and female individuals producing dissimilar gametes, predominates in over 94% of animal species excluding insects, requiring opposite-sex copulation for fertilization and species propagation.[41] This reproductive imperative is evident in the evolutionary conservation of sex-specific traits, such as sexual dimorphism and gamete specialization, which facilitate male-female pairing and have persisted since the emergence of anisogamy in early eukaryotes.[41] Mate choice experiments and ethological observations consistently demonstrate preferences for opposite-sex partners, driven by sensory cues including pheromones, visual displays, and vocalizations evolved to signal reproductive readiness to the opposite sex. In nonhuman mammals, females actively select mates based on traits advertising genetic quality and resource provision, as seen in olfactory and visual preferences during estrus.[42] Among birds, over 90% of species form socially monogamous pair bonds between males and females, with behaviors like mutual preening and territory defense reinforcing these heterosexual unions for breeding success.[43] In insects, such as hoverflies, males pursue and grasp females in mid-air for copulation, exemplifying species-typical heterosexual aerial mating rituals observed ubiquitously in dipterans.[44] While same-sex sexual behaviors occur in a minority of cases, documented in approximately 4% of mammalian species, reproductive fitness derives solely from heterosexual interactions, as same-sex acts yield no offspring.[45] Exclusive same-sex orientation remains rare, confined to subsets like 8-10% of male domestic sheep, underscoring heterosexuality's dominance in sustaining population viability across taxa.[46] Prenatal hormonal influences further orient adult behaviors toward opposite-sex attraction in species like rodents, where disruptions lead to atypical preferences but default to heterosexual norms under natural conditions.[47]Demographics and Prevalence

Global and Historical Statistics

Contemporary surveys consistently report heterosexuality as the most prevalent sexual orientation worldwide, with self-identification rates averaging 80% to 90% among adults. A 2021 Ipsos global survey across 27 countries found that 80% of respondents identified as heterosexual, 3% as gay or lesbian, 4% as bisexual, and smaller percentages for other categories, with variations by nation reflecting cultural attitudes toward disclosure—higher in Eastern Europe (e.g., 91% in Hungary) and lower in Latin America (e.g., 71% in Brazil).[48] [49] Similar patterns emerge in other multinational studies; for example, analysis of data from 28 nations involving 191,088 participants indicated majority heterosexuality for both sexes, though exact aggregates varied by assessment method (e.g., identity vs. attraction).[5] In the United States, national polls show heterosexuality comprising 85% to 96% of the adult population, with a noted decline in self-reported rates over recent decades. Gallup telephone surveys of over 10,000 adults annually report 85.7% identifying as straight in 2025 (down from 96.5% non-LGBT in 2012), with the increase in non-heterosexual identifications concentrated among younger generations and women.[50] [51] The Williams Institute, using 2020–2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data from state health surveys, estimates 94.5% of U.S. adults as non-LGBT, aligning with 13.9 million LGBT individuals out of approximately 258 million adults.[4]| Survey/Source | Year | Scope | % Identifying as Heterosexual/Straight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ipsos Global Survey | 2021 | 27 countries | 80%[48] |

| Gallup Poll | 2025 | U.S. adults | 85.7%[50] |

| Williams Institute (BRFSS) | 2020–2021 | U.S. adults | 94.5%[4] |

| National Academy of Sciences (GSS aggregate) | 2008–2012 | U.S. adults | ~97% (3% LGB)[52] |

.svg/232px-Gender_symbols_(4_colors).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Gender_symbols_(4_colors).svg.png)