Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hydroxide

View on Wikipedia | |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Hydroxide

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Oxidanide (not recommended) | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| OH− | |||

| Molar mass | 17.007 g·mol−1 | ||

| Basicity (pKb) | 0.0 [1] | ||

| Conjugate acid | Water | ||

| Conjugate base | Oxide anion | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds

|

O2H+ OH• O22− H2O | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Hydroxide is a diatomic anion with chemical formula OH−. It consists of an oxygen and hydrogen atom held together by a single covalent bond, and carries a negative electric charge. It is an important but usually minor constituent of water. It functions as a base, a ligand, a nucleophile, and a catalyst. The hydroxide ion forms salts, some of which dissociate in aqueous solution, liberating solvated hydroxide ions. Sodium hydroxide is a multi-million-ton per annum commodity chemical. The corresponding electrically neutral compound HO• is the hydroxyl radical. The corresponding covalently bound group −OH of atoms is the hydroxy group. Both the hydroxide ion and hydroxy group are nucleophiles and can act as catalysts in organic chemistry.

Many inorganic substances which bear the word hydroxide in their names are not ionic compounds of the hydroxide ion, but covalent compounds which contain hydroxy groups.

Hydroxide ion

[edit]The hydroxide ion is naturally produced from water by the self-ionization reaction:[2]

- H3O+ + OH− ⇌ 2H2O

The equilibrium constant for this reaction, defined as

- Kw = [H+][OH−][note 1]

has a value close to 10−14 at 25 °C, so the concentration of hydroxide ions in pure water is close to 10−7 mol∙dm−3, to satisfy the equal charge constraint. The pH of a solution is equal to the decimal cologarithm of the hydrogen cation concentration;[note 2] the pH of pure water is close to 7 at ambient temperatures. The concentration of hydroxide ions can be expressed in terms of pOH, which is close to (14 − pH),[note 3] so the pOH of pure water is also close to 7. Addition of a base to water will reduce the hydrogen cation concentration and therefore increase the hydroxide ion concentration (decrease pH, increase pOH) even if the base does not itself contain hydroxide. For example, ammonia solutions have a pH greater than 7 due to the reaction NH3 + H+ ⇌ NH+

4, which decreases the hydrogen cation concentration, which increases the hydroxide ion concentration. pOH can be kept at a nearly constant value with various buffer solutions.

In an aqueous solution[4] the hydroxide ion is a base in the Brønsted–Lowry sense as it can accept a proton[note 4] from a Brønsted–Lowry acid to form a water molecule. It can also act as a Lewis base by donating a pair of electrons to a Lewis acid. In aqueous solution both hydrogen ions and hydroxide ions are strongly solvated, with hydrogen bonds between oxygen and hydrogen atoms. Indeed, the bihydroxide ion H

3O−

2 has been characterized in the solid state. This compound is centrosymmetric and has a very short hydrogen bond (114.5 pm) that is similar to the length in the bifluoride ion HF−

2 (114 pm).[3] In aqueous solution the hydroxide ion forms strong hydrogen bonds with water molecules. A consequence of this is that concentrated solutions of sodium hydroxide have high viscosity due to the formation of an extended network of hydrogen bonds as in hydrogen fluoride solutions.

In solution, exposed to air, the hydroxide ion reacts rapidly with atmospheric carbon dioxide, which acts as a lewis acid, to form, initially, the bicarbonate ion.

- OH− + CO2 ⇌ HCO−

3

The equilibrium constant for this reaction can be specified either as a reaction with dissolved carbon dioxide or as a reaction with carbon dioxide gas (see Carbonic acid for values and details). At neutral or acid pH, the reaction is slow, but is catalyzed by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, which effectively creates hydroxide ions at the active site.

Solutions containing the hydroxide ion attack glass. In this case, the silicates in glass are acting as acids. Basic hydroxides, whether solids or in solution, are stored in airtight plastic containers.

The hydroxide ion can function as a typical electron-pair donor ligand, forming such complexes as tetrahydroxoaluminate/tetrahydroxidoaluminate [Al(OH)4]−. It is also often found in mixed-ligand complexes of the type [MLx(OH)y]z+, where L is a ligand. The hydroxide ion often serves as a bridging ligand, donating one pair of electrons to each of the atoms being bridged. As illustrated by [Pb2(OH)]3+, metal hydroxides are often written in a simplified format. It can even act as a 3-electron-pair donor, as in the tetramer [PtMe3(OH)]4.[5]

When bound to a strongly electron-withdrawing metal centre, hydroxide ligands tend to ionise into oxide ligands. For example, the bichromate ion [HCrO4]− dissociates according to

- [O3CrO–H]− ⇌ [CrO4]2− + H+

with a pKa of about 5.9.[6]

Vibrational spectra

[edit]The infrared spectra of compounds containing the OH functional group have strong absorption bands in the region centered around 3500 cm−1.[7] The high frequency of molecular vibration is a consequence of the small mass of the hydrogen atom as compared to the mass of the oxygen atom, and this makes detection of hydroxyl groups by infrared spectroscopy relatively easy. A band due to an OH group tends to be sharp. However, the band width increases when the OH group is involved in hydrogen bonding. A water molecule has an HOH bending mode at about 1600 cm−1, so the absence of this band can be used to distinguish an OH group from a water molecule.

When the OH group is bound to a metal ion in a coordination complex, an M−OH bending mode can be observed. For example, in [Sn(OH)6]2− it occurs at 1065 cm−1. The bending mode for a bridging hydroxide tends to be at a lower frequency as in [(bipyridine)Cu(OH)2Cu(bipyridine)]2+ (955 cm−1).[8] M−OH stretching vibrations occur below about 600 cm−1. For example, the tetrahedral ion [Zn(OH)4]2− has bands at 470 cm−1 (Raman-active, polarized) and 420 cm−1 (infrared). The same ion has a (HO)–Zn–(OH) bending vibration at 300 cm−1.[9]

Applications

[edit]Sodium hydroxide solutions, also known as lye and caustic soda, are used in the manufacture of pulp and paper, textiles, drinking water, soaps and detergents, and as a drain cleaner. Worldwide production in 2004 was approximately 60 million tonnes.[10] The principal method of manufacture is the chloralkali process.

Solutions containing the hydroxide ion are generated when a salt of a weak acid is dissolved in water. Sodium carbonate is used as an alkali, for example, by virtue of the hydrolysis reaction

- CO2−

3 + H2O ⇌ HCO−

3 + OH− (pKa2 = 10.33 at 25 °C and zero ionic strength)

An example of the use of sodium carbonate as an alkali is when washing soda (another name for sodium carbonate) acts on insoluble esters, such as triglycerides, commonly known as fats, to hydrolyze them and make them soluble.

Bauxite, a basic hydroxide of aluminium, is the principal ore from which the metal is manufactured.[11] Similarly, goethite (α-FeO(OH)) and lepidocrocite (γ-FeO(OH)), basic hydroxides of iron, are among the principal ores used for the manufacture of metallic iron.[12]

Inorganic hydroxides

[edit]Alkali metals

[edit]Aside from NaOH and KOH, which enjoy very large scale applications, the hydroxides of the other alkali metals also are useful. Lithium hydroxide (LiOH) is used in breathing gas purification systems for spacecraft, submarines, and rebreathers to remove carbon dioxide from exhaled gas.[13]

- 2 LiOH + CO2 → Li2CO3 + H2O

The hydroxide of lithium is preferred to that of sodium because of its lower mass. Sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, and the hydroxides of the other alkali metals are also strong bases.[14]

Alkaline earth metals

[edit]

Beryllium hydroxide Be(OH)2 is amphoteric.[15] The hydroxide itself is insoluble in water, with a solubility product log K*sp of −11.7. Addition of acid gives soluble hydrolysis products, including the trimeric ion [Be3(OH)3(H2O)6]3+, which has OH groups bridging between pairs of beryllium ions making a 6-membered ring.[16] At very low pH the aqua ion [Be(H2O)4]2+ is formed. Addition of hydroxide to Be(OH)2 gives the soluble tetrahydroxoberyllate or tetrahydroxidoberyllate anion, [Be(OH)4]2−.

The solubility in water of the other hydroxides in this group increases with increasing atomic number.[17] Magnesium hydroxide Mg(OH)2 is a strong base (up to the limit of its solubility, which is very low in pure water), as are the hydroxides of the heavier alkaline earths: calcium hydroxide, strontium hydroxide, and barium hydroxide. A solution or suspension of calcium hydroxide is known as limewater and can be used to test for the weak acid carbon dioxide. The reaction Ca(OH)2 + CO2 ⇌ Ca2+ + HCO−

3 + OH− illustrates the basicity of calcium hydroxide. Soda lime, which is a mixture of the strong bases NaOH and KOH with Ca(OH)2, is used as a CO2 absorbent.

Boron group elements

[edit]

The simplest hydroxide of boron B(OH)3, known as boric acid, is an acid. Unlike the hydroxides of the alkali and alkaline earth hydroxides, it does not dissociate in aqueous solution. Instead, it reacts with water molecules acting as a Lewis acid, releasing protons.

- B(OH)3 + H2O ⇌ B(OH)−

4 + H+

A variety of oxyanions of boron are known, which, in the protonated form, contain hydroxide groups.[18]

aluminate(III) ion

Aluminium hydroxide Al(OH)3 is amphoteric and dissolves in alkaline solution.[15]

- Al(OH)3 (solid) + OH− (aq) ⇌ Al(OH)−

4 (aq)

In the Bayer process[19] for the production of pure aluminium oxide from bauxite minerals this equilibrium is manipulated by careful control of temperature and alkali concentration. In the first phase, aluminium dissolves in hot alkaline solution as Al(OH)−

4, but other hydroxides usually present in the mineral, such as iron hydroxides, do not dissolve because they are not amphoteric. After removal of the insolubles, the so-called red mud, pure aluminium hydroxide is made to precipitate by reducing the temperature and adding water to the extract, which, by diluting the alkali, lowers the pH of the solution. Basic aluminium hydroxide AlO(OH), which may be present in bauxite, is also amphoteric.

In mildly acidic solutions, the hydroxo/hydroxido complexes formed by aluminium are somewhat different from those of boron, reflecting the greater size of Al(III) vs. B(III). The concentration of the species [Al13(OH)32]7+ is very dependent on the total aluminium concentration. Various other hydroxo complexes are found in crystalline compounds. Perhaps the most important is the basic hydroxide AlO(OH), a polymeric material known by the names of the mineral forms boehmite or diaspore, depending on crystal structure. Gallium hydroxide,[15] indium hydroxide, and thallium(III) hydroxide are also amphoteric. Thallium(I) hydroxide is a strong base.[20]

Carbon group elements

[edit]Carbon forms no simple hydroxides. The hypothetical compound C(OH)4 (orthocarbonic acid or methanetetrol) is unstable in aqueous solution:[21]

- C(OH)4 → HCO−

3 + H3O+ - HCO−

3 + H+ ⇌ H2CO3

Carbon dioxide is also known as carbonic anhydride, meaning that it forms by dehydration of carbonic acid H2CO3 (OC(OH)2).[22]

Silicic acid is the name given to a variety of compounds with a generic formula [SiOx(OH)4−2x]n.[23][24] Orthosilicic acid has been identified in very dilute aqueous solution. It is a weak acid with pKa1 = 9.84, pKa2 = 13.2 at 25 °C. It can be written as H4SiO4 or Si(OH)4.[6] Other silicic acids such as metasilicic acid (H2SiO3), disilicic acid (H2Si2O5), and pyrosilicic acid (H6Si2O7) have been characterized. These acids also have hydroxide groups attached to the silicon; the formulas suggest that these acids are protonated forms of polyoxyanions.

Few hydroxo complexes of germanium have been characterized. Tin(II) hydroxide Sn(OH)2 was prepared in anhydrous media. When tin(II) oxide is treated with alkali the pyramidal hydroxo complex Sn(OH)−

3 is formed. When solutions containing this ion are acidified, the ion [Sn3(OH)4]2+ is formed together with some basic hydroxo complexes. The structure of [Sn3(OH)4]2+ has a triangle of tin atoms connected by bridging hydroxide groups.[25] Tin(IV) hydroxide is unknown but can be regarded as the hypothetical acid from which stannates, with a formula [Sn(OH)6]2−, are derived by reaction with the (Lewis) basic hydroxide ion.[26]

Hydrolysis of Pb2+ in aqueous solution is accompanied by the formation of various hydroxo-containing complexes, some of which are insoluble. The basic hydroxo complex [Pb6O(OH)6]4+ is a cluster of six lead centres with metal–metal bonds surrounding a central oxide ion. The six hydroxide groups lie on the faces of the two external Pb4 tetrahedra. In strongly alkaline solutions soluble plumbate ions are formed, including [Pb(OH)6]2−.[27]

Other main-group elements

[edit] |

|

|

|

|

|

| Phosphorous acid | Phosphoric acid | Sulfuric acid | Telluric acid | Orthoperiodic acid | Xenic acid |

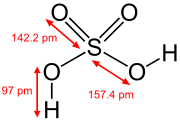

In the higher oxidation states of the pnictogens, chalcogens, halogens, and noble gases there are oxoacids in which the central atom is attached to oxide ions and hydroxide ions. Examples include phosphoric acid H3PO4, and sulfuric acid H2SO4. In these compounds one or more hydroxide groups can dissociate with the liberation of hydrogen cations as in a standard Brønsted–Lowry acid. Many oxoacids of sulfur are known and all feature OH groups that can dissociate.[28]

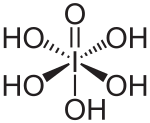

Telluric acid is often written with the formula H2TeO4·2H2O but is better described structurally as Te(OH)6.[29]

Orthoperiodic acid[note 6] can lose all its protons, eventually forming the periodate ion [IO4]−. It can also be protonated in strongly acidic conditions to give the octahedral ion [I(OH)6]+, completing the isoelectronic series, [E(OH)6]z, E = Sn, Sb, Te, I; z = −2, −1, 0, +1. Other acids of iodine(VII) that contain hydroxide groups are known, in particular in salts such as the mesoperiodate ion that occurs in K4[I2O8(OH)2]·8H2O.[30]

As is common outside of the alkali metals, hydroxides of the elements in lower oxidation states are complicated. For example, phosphorous acid H3PO3 predominantly has the structure OP(H)(OH)2, in equilibrium with a small amount of P(OH)3.[31][32]

The oxoacids of chlorine, bromine, and iodine have the formula On−1/2A(OH), where n is the oxidation number: +1, +3, +5, or +7, and A = Cl, Br, or I. The only oxoacid of fluorine is F(OH), hypofluorous acid. When these acids are neutralized the hydrogen atom is removed from the hydroxide group.[33]

Transition and post-transition metals

[edit]The hydroxides of the transition metals and post-transition metals usually have the metal in the +2 (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) or +3 (M = Fe, Ru, Rh, Ir) oxidation state. None are soluble in water, and many are poorly defined. One complicating feature of the hydroxides is their tendency to undergo further condensation to the oxides, a process called olation. Hydroxides of metals in the +1 oxidation state are also poorly defined or unstable. For example, silver hydroxide Ag(OH) decomposes spontaneously to the oxide (Ag2O). Copper(I) and gold(I) hydroxides are also unstable, although stable adducts of CuOH and AuOH are known.[34] The polymeric compounds M(OH)2 and M(OH)3 are in general prepared by increasing the pH of an aqueous solution of the corresponding metal cation until the hydroxide precipitates out of solution. On the converse, the hydroxides dissolve in acidic solution. Zinc hydroxide Zn(OH)2 is amphoteric, forming the tetrahydroxidozincate ion Zn(OH)2−

4 in strongly alkaline solution.[15]

Numerous mixed ligand complexes of these metals with the hydroxide ion exist. In fact, these are in general better defined than the simpler derivatives. Many can be made by deprotonation of the corresponding metal aquo complex.

- LnM(OH2) + B ⇌ LnM(OH)– + BH+ (L = ligand, B = base)

Vanadic acid H3VO4 shows similarities with phosphoric acid H3PO4 though it has a much more complex vanadate oxoanion chemistry. Chromic acid H2CrO4, has similarities with sulfuric acid H2SO4; for example, both form acid salts A+[HMO4]−. Some metals, e.g. V, Cr, Nb, Ta, Mo, W, tend to exist in high oxidation states. Rather than forming hydroxides in aqueous solution, they convert to oxo clusters by the process of olation, forming polyoxometalates.[35]

Basic salts containing hydroxide

[edit]In some cases, the products of partial hydrolysis of metal ion, described above, can be found in crystalline compounds. A striking example is found with zirconium(IV). Because of the high oxidation state, salts of Zr4+ are extensively hydrolyzed in water even at low pH. The compound originally formulated as ZrOCl2·8H2O was found to be the chloride salt of a tetrameric cation [Zr4(OH)8(H2O)16]8+ in which there is a square of Zr4+ ions with two hydroxide groups bridging between Zr atoms on each side of the square and with four water molecules attached to each Zr atom.[36]

The mineral malachite is a typical example of a basic carbonate. The formula, Cu2CO3(OH)2 shows that it is halfway between copper carbonate and copper hydroxide. Indeed, in the past the formula was written as CuCO3·Cu(OH)2. The crystal structure is made up of copper, carbonate and hydroxide ions.[36] The mineral atacamite is an example of a basic chloride. It has the formula Cu2Cl(OH)3. In this case the composition is nearer to that of the hydroxide than that of the chloride: CuCl2·3Cu(OH)2.[37] Copper forms hydroxyphosphate (libethenite), arsenate (olivenite), sulfate (brochantite), and nitrate compounds. White lead is a basic lead carbonate, (PbCO3)2·Pb(OH)2, which has been used as a white pigment because of its opaque quality, though its use is now restricted because it can be a source for lead poisoning.[36]

Structural chemistry

[edit]The hydroxide ion appears to rotate freely in crystals of the heavier alkali metal hydroxides at higher temperatures so as to present itself as a spherical ion, with an effective ionic radius of about 153 pm.[38] Thus, the high-temperature forms of KOH and NaOH have the sodium chloride structure,[39] which gradually freezes in a monoclinically distorted sodium chloride structure at temperatures below about 300 °C. The OH groups still rotate even at room temperature around their symmetry axes and, therefore, cannot be detected by X-ray diffraction.[40] The room-temperature form of NaOH has the thallium iodide structure. LiOH, however, has a layered structure, made up of tetrahedral Li(OH)4 and (OH)Li4 units.[38] This is consistent with the weakly basic character of LiOH in solution, indicating that the Li–OH bond has much covalent character.

The hydroxide ion displays cylindrical symmetry in hydroxides of divalent metals Ca, Cd, Mn, Fe, and Co. For example, magnesium hydroxide Mg(OH)2 (brucite) crystallizes with the cadmium iodide layer structure, with a kind of close-packing of magnesium and hydroxide ions.[38][41]

The amphoteric hydroxide Al(OH)3 has four major crystalline forms: gibbsite (most stable), bayerite, nordstrandite, and doyleite.[note 7] All these polymorphs are built up of double layers of hydroxide ions—the aluminium atoms on two-thirds of the octahedral holes between the two layers—and differ only in the stacking sequence of the layers.[42] The structures are similar to the brucite structure. However, whereas the brucite structure can be described as a close-packed structure, in gibbsite the OH groups on the underside of one layer rest on the groups of the layer below. This arrangement led to the suggestion that there are directional bonds between OH groups in adjacent layers.[43] This is an unusual form of hydrogen bonding since the two hydroxide ions involved would be expected to point away from each other. The hydrogen atoms have been located by neutron diffraction experiments on α-AlO(OH) (diaspore). The O–H–O distance is very short, at 265 pm; the hydrogen is not equidistant between the oxygen atoms and the short OH bond makes an angle of 12° with the O–O line.[44] A similar type of hydrogen bond has been proposed for other amphoteric hydroxides, including Be(OH)2, Zn(OH)2, and Fe(OH)3.[38]

A number of mixed hydroxides are known with stoichiometry A3MIII(OH)6, A2MIV(OH)6, and AMV(OH)6. As the formula suggests these substances contain M(OH)6 octahedral structural units.[45] Layered double hydroxides may be represented by the formula [Mz+

1−xM3+

x(OH)

2]q+(Xn−)

q⁄n·yH

2O. Most commonly, z = 2, and M2+ = Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, or Zn2+; hence q = x.

Organic reactions

[edit]Potassium hydroxide and sodium hydroxide are two well-known reagents in organic chemistry.

Base catalysis

[edit]The hydroxide ion may act as a base catalyst.[46] The base abstracts a proton from a weak acid to give an intermediate that goes on to react with another reagent. Common substrates for proton abstraction are alcohols, phenols, amines, and carbon acids. The pKa value for dissociation of a C–H bond is extremely high, but the pKa alpha hydrogens of a carbonyl compound are about 3 log units lower. Typical pKa values are 16.7 for acetaldehyde and 19 for acetone.[47] Dissociation can occur in the presence of a suitable base.

- RC(O)CH2R' + B ⇌ RC(O)CH−R' + BH+

The base should have a pKa value not less than about 4 log units smaller, or the equilibrium will lie almost completely to the left.

The hydroxide ion by itself is not a strong enough base, but it can be converted to one by adding sodium hydroxide to ethanol

- OH− + EtOH ⇌ EtO− + H2O

to produce the ethoxide ion. The pKa for self-dissociation of ethanol is about 16, so the alkoxide ion is a strong enough base.[48] The addition of an alcohol to an aldehyde to form a hemiacetal is an example of a reaction that can be catalyzed by the presence of hydroxide. Hydroxide can also act as a Lewis-base catalyst.[49]

As a nucleophilic reagent

[edit]

The hydroxide ion is intermediate in nucleophilicity between the fluoride ion F−, and the amide ion NH−

2.[50] Ester hydrolysis under alkaline conditions (also known as base hydrolysis)

- R1C(O)OR2 + OH− ⇌ R1CO(O)H + −OR2 ⇌ R1CO2− + HOR2

is an example of a hydroxide ion serving as a nucleophile.[51]

Early methods for manufacturing soap treated triglycerides from animal fat (the ester) with lye.

Other cases where hydroxide can act as a nucleophilic reagent are amide hydrolysis, the Cannizzaro reaction, nucleophilic aliphatic substitution, nucleophilic aromatic substitution, and in elimination reactions. The reaction medium for KOH and NaOH is usually water but with a phase-transfer catalyst the hydroxide anion can be shuttled into an organic solvent as well, for example in the generation of the reactive intermediate dichlorocarbene.

Notes

[edit]- ^ [H+] denotes the concentration of hydrogen cations and [OH−] the concentration of hydroxide ions

- ^ Strictly speaking pH is the cologarithm of the hydrogen cation activity

- ^ pOH signifies the negative logarithm to base 10 of [OH−], alternatively the logarithm of 1/[OH−]

- ^ In this context proton is the term used for a solvated hydrogen cation

- ^ In aqueous solution the ligands L are water molecules, but they may be replaced by other ligands

- ^ The name is not derived from "period", but from "iodine": periodic acid (compare iodic acid, perchloric acid), and it is thus pronounced per-iodic /ˌpɜːraɪˈɒdɪk/ PUR-eye-OD-ik, and not as /ˌpɪərɪ-/ PEER-ee-.

- ^ Crystal structures are illustrated at Web mineral: Gibbsite, Bayerite, Norstrandite and Doyleite

References

[edit]- ^ Neils, T.L.; Schaertel, S. and Silverstein, T.P. (2024). "The pKa of Water and the Fundamental Laws Describing Solution Equilibria: An Appeal for a Consistent Thermodynamic Pedagogy". Helv. Chim. Acta. 107 (11) e202400103. Bibcode:2024HChAc.107E0103N. doi:10.1002/hlca.202400103.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Geissler, P. L.; Dellago, C.; Chandler, D.; Hutter, J.; Parrinello, M. (2001). "Autoionization in liquid water" (PDF). Science. 291 (5511): 2121–2124. Bibcode:2001Sci...291.2121G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.6.4964. doi:10.1126/science.1056991. PMID 11251111. S2CID 1081091. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-25. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ a b Kamal Abu-Dari; Kenneth N. Raymond; Derek P. Freyberg (1979). "The bihydroxide (H

3O−

2) anion. A very short, symmetric hydrogen bond". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101 (13): 3688–3689. doi:10.1021/ja00507a059. - ^ Marx, D.; Chandra, A; Tuckerman, M.E. (2010). "Aqueous Basic Solutions: Hydroxide Solvation, Structural Diffusion, and Comparison to the Hydrated Proton". Chem. Rev. 110 (4): 2174–2216. doi:10.1021/cr900233f. PMID 20170203.

- ^ Greenwood, p. 1168

- ^ a b IUPAC SC-Database Archived 2017-06-19 at the Wayback Machine A comprehensive database of published data on equilibrium constants of metal complexes and ligands

- ^ Nakamoto, K. (1997). Infrared and Raman spectra of Inorganic and Coordination compounds. Part A (5th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-16394-7.

- ^ Nakamoto, Part B, p. 57

- ^ Adams, D.M. (1967). Metal–Ligand and Related Vibrations. London: Edward Arnold. Chapter 5.

- ^ Cetin Kurt, Jürgen Bittner. "Sodium Hydroxide". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_345.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). "Aluminium". Nature's Building Blocks: An A–Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). "Aluminium". Nature's Building Blocks: An A–Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- ^ Jaunsen, JR (1989). "The Behavior and Capabilities of Lithium Hydroxide Carbon Dioxide Scrubbers in a Deep Sea Environment". US Naval Academy Technical Report. USNA-TSPR-157. Archived from the original on 2009-08-24. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ^ Holleman, p. 1108

- ^ a b c d Thomas R. Dulski A manual for the chemical analysis of metals, ASTM International, 1996, ISBN 0-8031-2066-4 p. 100

- ^ Alderighi, L; Dominguez, S.; Gans, P.; Midollini, S.; Sabatini, A.; Vacca, A. (2009). "Beryllium binding to adenosine 5'-phosphates in aqueous solution at 25°C". J. Coord. Chem. 62 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1080/00958970802474862. S2CID 93623985.

- ^ Housecroft, p. 241

- ^ Housectroft, p. 263

- ^ Bayer process chemistry

- ^ James E. House Inorganic chemistry, Academic Press, 2008, ISBN 0-12-356786-6, p. 764

- ^ Böhm, Stanislav; Antipova, Diana; Kuthan, Josef (1997). "A study of methanetetraol dehydration to carbonic acid". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 62 (3): 315–322. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-461X(1997)62:3<315::AID-QUA10>3.0.CO;2-8. ISSN 1097-461X.

- ^ Greenwood, p. 310

- ^ Greenwood, p. 346

- ^ R. K. Iler, The Chemistry of Silica, Wiley, New York, 1979 ISBN 0-471-02404-X

- ^ Greenwood, p. 384

- ^ Greenwood, pp. 383–384

- ^ Greenwood, p. 395

- ^ Greenwood, p. 705

- ^ Greenwood, p. 781

- ^ Greenwood, pp. 873–874

- ^ M. N. Sokolov; E. V. Chubarova; K. A. Kovalenko; I. V. Mironov; A. V. Virovets; E. Peresypkina; V. P. Fedin (2005). "Stabilization of tautomeric forms P(OH)3 and HP(OH)2 and their derivatives by coordination to palladium and nickel atoms in heterometallic clusters with the Mo

3MQ4+

4 core (M = Ni, Pd; Q = S, Se)". Russian Chemical Bulletin. 54 (3): 615. doi:10.1007/s11172-005-0296-1. S2CID 93718865. - ^ Holleman, pp. 711–718

- ^ Greenwood, p. 853

- ^ Fortman, George C.; Slawin, Alexandra M. Z.; Nolan, Steven P. (2010). "A Versatile Cuprous Synthon: [Cu(IPr)(OH)] (IPr = 1,3 bis(diisopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene)". Organometallics. 29 (17): 3966–3972. doi:10.1021/om100733n.

- ^ Juan J. Borrás-Almenar, Eugenio Coronado, Achim Müller Polyoxometalate Molecular Science, Springer, 2003, ISBN 1-4020-1242-X, p. 4

- ^ a b c Wells, p. 561

- ^ Wells, p. 393

- ^ a b c d Wells, p. 548

- ^ Victoria M. Nield, David A. Keen Diffuse neutron scattering from crystalline materials, Oxford University Press, 2001 ISBN 0-19-851790-4, p. 276

- ^ Jacobs, H.; Kockelkorn, J.; Tacke, Th. (1985). "Hydroxide des Natriums, Kaliums und Rubidiums: Einkristallzüchtung und röntgenographische Strukturbestimmung an der bei Raumtemperatur stabilen Modifikation". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 531 (12): 119. Bibcode:1985ZAACh.531..119J. doi:10.1002/zaac.19855311217.

- ^ Enoki, Toshiaki; Tsujikawa, Ikuji (1975). "Magnetic Behaviours of a Random Magnet, NipMg1−p(OH)2". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 39 (2): 317. Bibcode:1975JPSJ...39..317E. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.39.317.

- ^ Athanasios K. Karamalidis, David A. Dzombak Surface Complexation Modeling: Gibbsite, John Wiley and Sons, 2010 ISBN 0-470-58768-7 pp. 15 ff

- ^ Bernal, J.D.; Megaw, H.D. (1935). "The Function of Hydrogen in Intermolecular Forces". Proc. R. Soc. A. 151 (873): 384–420. Bibcode:1935RSPSA.151..384B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1935.0157.

- ^ Wells, p. 557

- ^ Wells, p. 555

- ^ Hattori, H.; Misono, M.; Ono, Y., eds. (1994). Acid–Base catalysis II. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-98655-9.

- ^ Ouellette, R.J. and Rawn, J.D. "Organic Chemistry" 1st Ed. Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1996: New Jersey. ISBN 0-02-390171-3.

- ^ Pine, S.H.; Hendrickson, J.B.; Cram, D.J.; Hammond, G.S. (1980). Organic chemistry. McGraw–Hill. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-07-050115-7.

- ^ Denmark, S.E.; Beutne, G.L. (2008). "Lewis Base Catalysis in Organic Synthesis". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 47 (9): 1560–1638. Bibcode:2008ACIE...47.1560D. doi:10.1002/anie.200604943. PMID 18236505.

- ^ Mullins, J. J. (2008). "Six Pillars of Organic Chemistry". J. Chem. Educ. 85 (1): 83. Bibcode:2008JChEd..85...83M. doi:10.1021/ed085p83.pdf Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hardinger, Steven A. (2017). "Illustrated Glossary of Organic Chemistry: Saponification". Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, UCLA. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Holleman, A.F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Academic press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2008). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Shriver, D.F; Atkins, P.W (1999). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850330-9.

- Wells, A.F (1962). Structural Inorganic Chemistry (3rd. ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855125-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)