Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Long title | Joint Resolution to authorise the use of United States Armed Forces against Iraq |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Iraq Resolution |

| Enacted by | the 107th United States Congress |

| Effective | October 16, 2002 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub. L. 107–243 (text) (PDF) |

| Statutes at Large | 116 Stat. 1498 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002,[1] informally known as the Iraq Resolution, is a joint resolution passed by the United States Congress in October 2002 as Public Law No. 107-243, authorizing the use of the United States Armed Forces against Saddam Hussein's Iraq government in what would be known as Operation Iraqi Freedom.[2]

Contents

[edit]The resolution cited many factors as justifying the use of military force against Iraq:[3][4]

- Iraq's noncompliance with the conditions of the 1991 ceasefire agreement, including interference with U.N. weapons inspectors.

- Iraq "continuing to possess and develop a significant chemical and biological weapons capability" and "actively seeking a nuclear weapons capability" posed a "threat to the national security of the United States and international peace and security in the Persian Gulf region."

- Iraq's "brutal repression of its civilian population."

- Iraq's "capability and willingness to use weapons of mass destruction against other nations and its own people".

- Iraq's hostility towards the United States as demonstrated by the 1993 assassination attempt on former President George H. W. Bush and firing on coalition aircraft enforcing the no-fly zones following the 1991 Gulf War.

- Members of al-Qaeda, an organization bearing responsibility for attacks on the United States, its citizens, and interests, including the attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, are known to be in Iraq.

- Iraq's "continu[ing] to aid and harbor other international terrorist organizations," including anti-United States terrorist organizations.

- Iraq paid bounty to families of suicide bombers.

- The efforts by the Congress and the President to fight terrorists, and those who aided or harbored them.

- The authorization by the Constitution and the Congress for the President to fight anti-United States terrorism.

- The governments in Israel, Turkey, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia feared Saddam and wanted him removed from power.

- Citing the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, the resolution reiterated that it should be the policy of the United States to remove the Saddam Hussein regime and promote a democratic replacement.

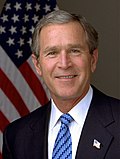

The resolution "supported" and "encouraged" diplomatic efforts by President George W. Bush to "strictly enforce through the U.N. Security Council all relevant Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq" and "obtain prompt and decisive action by the Security Council to ensure that Iraq abandons its strategy of delay, evasion, and noncompliance and promptly and strictly complies with all relevant Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq."

The resolution authorized President Bush to use the Armed Forces of the United States "as he determines to be necessary and appropriate" in order to "defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq; and enforce all relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions regarding Iraq."

Passage

[edit]An authorization by Congress was sought by President George W. Bush soon after his September 12, 2002 statement before the U.N. General Assembly asking for quick action by the Security Council in enforcing the resolutions against Iraq.[5][6]

Of the legislation introduced by Congress in response to President Bush's requests,[7] S.J.Res. 45 sponsored by Sen. Daschle and Sen. Lott was based on the original White House proposal authorizing the use of force in Iraq, H.J.Res. 114 sponsored by Rep. Hastert and Rep. Gephardt and the substantially similar S.J.Res. 46 sponsored by Sen. Lieberman were modified proposals. H.J.Res. 110 sponsored by Rep. Hastings was a separate proposal never considered on the floor. Eventually, the Hastert–Gephardt proposal became the legislation Congress focused on.

Passage of the full resolution

[edit]Introduced in Congress on October 2, 2002, in conjunction with the Administration's proposals,[3][8] H.J.Res. 114 passed the House of Representatives on Thursday afternoon at 3:05 p.m. EDT on October 10, 2002, by a vote of 296–133,[9] and passed the Senate after midnight early Friday morning, at 12:50 a.m. EDT on October 11, 2002, by a vote of 77–23.[10] It was signed into law as Pub. L. 107–243 (text) (PDF) by President Bush on October 16, 2002.

United States House of Representatives

[edit]| Party | Yeas | Nays | Not Voting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | 215 | 6 | 2 |

| Democratic | 81 | 126 | 1 |

| Independent | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| TOTALS | 296 | 133 | 3 |

- 215 (96.4%) of 223 Republican Representatives voted for the resolution.

- 81 (39.2%) of 208 Democratic Representatives voted for the resolution.

- 6 (<2.7%) of 223 Republican Representatives voted against the resolution: Reps. Duncan (R-TN), Hostettler (R-IN), Houghton (R-NY), Leach (R-IA), Morella (R-MD), Paul (R-TX).

- 126 (~60.3%) of 209 Democratic Representatives voted against the resolution.

- The only Independent Representative voted against the resolution: Rep. Sanders (I-VT)

United States Senate

[edit]| Party | Yeas | Nays |

|---|---|---|

| Republican | 48 | 1 |

| Democratic | 29 | 21 |

| Independent | 0 | 1 |

| TOTALS | 77 | 23 |

- 29 (58%) of 50 Democratic senators voted for the resolution. Those voting for the resolution were:

Sens. Baucus (D-MT), Bayh (D-IN), Biden (D-DE), Breaux (D-LA), Cantwell (D-WA), Carnahan (D-MO), Carper (D-DE), Cleland (D-GA), Clinton (D-NY), Daschle (D-SD), Dodd (D-CT), Dorgan (D-ND), Edwards (D-NC), Feinstein (D-CA), Harkin (D-IA), Hollings (D-SC), Johnson (D-SD), Kerry (D-MA), Kohl (D-WI), Landrieu (D-LA), Lieberman (D-CT), Lincoln (D-AR), Miller (D-GA), Nelson (D-FL), Nelson (D-NE), Reid (D-NV), Rockefeller (D-WV), Schumer (D-NY), and Torricelli (D-NJ).

- 21 (42%) of 50 Democratic Senators voted against the resolution. Those voting against the resolution were:

Sens. Akaka (D-HI), Bingaman (D-NM), Boxer (D-CA), Byrd (D-WV), Conrad (D-ND), Corzine (D-NJ), Dayton (D-MN), Durbin (D-IL), Feingold (D-WI), Graham (D-FL), Inouye (D-HI), Kennedy (D-MA), Leahy (D-VT), Levin (D-MI), Mikulski (D-MD), Murray (D-WA), Reed (D-RI), Sarbanes (D-MD), Stabenow (D-MI), Wellstone (D-MN), and Wyden (D-OR).

- 1 (2%) of 49 Republican senators voted against the resolution: Sen. Chafee (R-RI).

- The only independent senator voted against the resolution: Sen. Jeffords (I-VT)

Amendments offered to the House Resolution

[edit]Lee Amendment

[edit]- Amendment in the nature of a substitute sought to have the United States work through the United Nations to seek to resolve the matter of ensuring that Iraq is not developing weapons of mass destruction, through mechanisms such as the resumption of weapons inspections, negotiation, enquiry, mediation, regional arrangements, and other peaceful means.

- Sponsored by Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA).[11]

- Failed by the Ayes and Nays: 72 – 355[12]

Spratt Amendment

[edit]- Amendment in the nature of a substitute sought to authorize the use of U.S. armed forces to support any new U.N. Security Council resolution that mandated the elimination, by force if necessary, of all Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, long-range ballistic missiles, and the means of producing such weapons and missiles. Requested that the President should seek authorization from Congress to use the armed forces of the U.S. in the absence of a U.N. Security Council resolution sufficient to eliminate, by force if necessary, all Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, long-range ballistic missiles, and the means of producing such weapons and missiles. Provided expedited consideration for authorization in the latter case.

- Sponsored by Rep. John Spratt (D-SC-5).[13]

- Failed by the Yeas and Nays: 155 – 270[14]

- Sponsored by Rep. John Spratt (D-SC-5).[13]

House Rules Amendment

[edit]- An amendment considered as adopted pursuant to the provisions of H.Res. 574[15]

Amendments offered to the Senate Resolution

[edit]Byrd Amendments

[edit]- To provide statutory construction that constitutional authorities remain unaffected and that no additional grant of authority is made to the President not directly related to the existing threat posed by Iraq.

- Sponsored by Sen. Robert Byrd (D-WV).[18]

- Amendment SA 4868 not agreed to by Yea-Nay Vote: 14 – 86[19]

- Sponsored by Sen. Robert Byrd (D-WV).[18]

- To provide a termination date for the authorization of the use of the Armed Forces of the United States, together with procedures for the extension of such date unless Congress disapproves the extension.

- Sponsored by Sen. Robert Byrd (D-WV).[20]

- Amendment SA 4869 not agreed to by Yea-Nay Vote: 31 – 66[21]

- Sponsored by Sen. Robert Byrd (D-WV).[20]

Levin Amendment

[edit]- To authorize the use of the United States Armed Forces, pursuant to a new resolution of the United Nations Security Council, to destroy, remove, or render harmless Iraq's weapons of mass destruction, nuclear weapons-usable material, long-range ballistic missiles, and related facilities, and for other purposes.

- Sponsored by Sen. Carl Levin (D-MI).[22]

- Amendment SA 4862 not agreed to by Yea-Nay Vote: 24 – 75[23]

- Sponsored by Sen. Carl Levin (D-MI).[22]

Durbin Amendment

[edit]- To amend the authorization for the use of the Armed Forces to cover an imminent threat posed by Iraq's weapons of mass destruction rather than the continuing threat posed by Iraq.

- Sponsored by Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL).[24]

- Amendment SA 4865 not agreed to by Yea-Nay Vote: 30 – 70[25]

- Sponsored by Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL).[24]

Legal challenges

[edit]U.S. law

[edit]| Events leading up to the Iraq War |

|---|

|

|

The United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit refused to review the legality of the invasion in 2003, citing a lack of ripeness.

In early 2003, the Iraq Resolution was challenged in court to stop the invasion from happening. The plaintiffs argued that the President does not have the authority to declare war. The final decision came from a three-judge panel from the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit which dismissed the case. Judge Lynch wrote in the opinion that the Judiciary cannot intervene unless there is a fully developed conflict between the President and Congress or if Congress gave the President "absolute discretion" to declare war.[26]

Similar efforts to secure judicial review of the invasion's legality have been dismissed on a variety of justiciability grounds.

International law

[edit]The vast majority of international legal scholarship contended that the war was an illegal war of aggression, and United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan stated in 2004 that the invasion was illegal, and that it was "not in conformity with the UN Charter".[27][28]

U.N. security council resolutions

[edit]Debate about the legality of the 2003 invasion of Iraq under international law, centers around ambiguous language in parts of U.N. Resolution 1441 (2002).[29] The U.N. Charter in Article 39 states: "The Security Council shall determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression and shall make recommendations, or decide what measures shall be taken in accordance with Articles 41 and 42, to maintain or restore international peace and security".

The position of the U.S. and U.K. is that the invasion was authorized by a series of U.N. resolutions dating back to 1990 and that since the U.N. security council has made no Article 39[30] finding of illegality, that no illegality exists.

Resolution 1441 declared that Iraq was in "material breach" of the cease-fire under U.N. Resolution 687 (1991), which required cooperation with weapons inspectors. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states that under certain conditions, a party may invoke a "material breach" to suspend a multilateral treaty. Thus, the U.S. and U.K. claim that they used their right to suspend the cease-fire in Resolution 687 and to continue hostilities against Iraq under the authority of U.N. Resolution 678 (1990), which originally authorized the use of force after Iraq invaded Kuwait.[31] This is the same argument that was used for Operation Desert Fox in 1998.[32] They also contend that, while Resolution 1441 required the UNSC to assemble and assess reports from the weapons inspectors, it was not necessary for the UNSC to reach an agreement on the course of action. If, at that time, it was determined that Iraq breached Resolution 1441, the resolution did not "constrain any member state from acting to defend itself against the threat posed by Iraq".[33] The United States government argued, wholly apart from Resolution 1441, that it has a right of pre-emptive self-defense to protect itself from terrorism fomented by Iraq.[34]

It remains unclear whether any party other than the Security Council can make the determination that Iraq breached Resolution 1441, as U.N. members commented that it is not up to one member state to interpret and enforce U.N. resolutions for the entire council.[35] In addition, other nations have stated that a second resolution was required to initiate hostilities.[36]

Repeal

[edit]On June 17, 2021, the House of Representatives voted for House Resolution 256, to repeal the 2002 resolution by a vote of 268–161. 219 House Democrats and 49 House Republicans voted to repeal, while 160 Republicans and 1 Democrat voted to oppose the repeal.[37]

In July 2021, three Senators, Christopher Murphy, Mike Lee & Bernie Sanders, introduced S.2391, the National Security Powers Act of 2021, which would have repealed previous war authorizations and established new procedures,[38] but a Senator put a quasi-anonymous hold on it in committee until it was dead.[39] Its companion in the House, H.R.5410, the National Security Reforms and Accountability Act, did not contain the repeal language (which prevented the Senators' attempt to repeal),[40] and again, this companion bill was quasi-anonymously held in committee til it was dead.[41]

On March 16, 2023, a bill (S. 316) to repeal the 1991 and 2002 AUMFs, introduced by Senators Tim Kaine and Todd Young, was advanced by the Senate by 68 votes to 27,[42] but its companion, H.R.932, has been quasi-anonymously held by a Representative in the House Committee on Foreign Affairs since February 9, 2023.[43]

On July 13, 2023, in a further attempt to repeal the 1991 and 2002 AUMFs, Tim Kaine & Todd Young introduced S.Amdt.427 to S.2226, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024.[44] But they didn't timely propose it on the floor so that when the bill passed the Senate, no action was taken on their amendment & it was therefore, by default, excluded by law.[45] The POTUS remains authorized by Congress to strike at will, any targets of his choosing in Iraq.

See also

[edit]- 2003 invasion of Iraq

- Authorization for Use of Military Force

- British Parliamentary approval for the invasion of Iraq

- Command responsibility

- Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

- Jus ad bellum

- Just war theory

- Iraq War

- Legality of the Iraq War

- Legitimacy of the 2003 invasion of Iraq

- Rationale for the Iraq War

- United Nations

- United Nations Charter

- Views on the 2003 invasion of Iraq

- War of aggression

- War on terror

References

[edit]- ^ Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 (PDF)

- ^ "Joint Resolution to Authorize the Use of United States Armed Forces Against Iraq" (Press release). The Office of the President of the United States. Archived from the original on November 2, 2002.

- ^ a b "President, House Leadership Agree on Iraq Resolution" (Press release). The White House. 2002-10-02.

- ^ "President's Remarks at the United Nations General Assembly" (Press release). The White House. 2002-09-12.

- ^ "Remarks by the President after Meeting with Congressional Leaders" (Press release). The White House. 2002-09-18.

- ^ Legislation related to the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq, Congressional Record, Library of Congress.

- ^ Major Congressional Actions of H.J.Res. 114, Congressional Record, Library of Congress

- ^ "107th Congress-2nd Session 455th Roll Call Vote of by members of the House of Representatives".

- ^ "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 107th Congress – 2nd Session". www.senate.gov.

- ^ H.AMDT.608 – Amendment in the nature of a substitute of H.J.RES.114 Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, 107th Congress, U.S. House of Representatives, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ On Agreeing to the Lee of California Substitute Amendment, 107th Congress, U.S. House of Representatives, Clerk of the House, 2002-10-10

- ^ H.AMDT.609 – Amendment in the nature of a substitute of H.J.RES.114 Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, 107th Congress, U.S. House of Representatives, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ On Agreeing to the Spratt of South Carolina Substitute Amendment, 107th Congress, U.S. House of Representatives, Clerk of the House, 2002-10-10

- ^ H.RES.574 – Providing for the consideration of the joint resolution (H.J.RES.114)[permanent dead link], 107th Congress, U.S. House of Representatives, Library of Congress, 2002-10-08

- ^ H.AMDT.610 – Amendment considered as adopted pursuant to the provisions of H.Res.574 Archived 2016-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, 107th Congress, U.S. House of Representatives, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ On Agreeing to Resolve H.RES.574 Archived 2016-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, 107th Congress, U.S. House of Representatives, Library of Congress, 2002-10-08

- ^ S.AMDT.4868 – Providing for Statuary Construction in the Consideration of the Joint Resolution (S.J.RES.45) Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, 107th Congress, U.S. Senate, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ On Agreeing to the Amendment (Byrd Amdt. No. 4868), 107th Congress, U.S. Senate, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ S.AMDT.4869 – Providing for Congressional Construction in the Consideration of the Joint Resolution (S.J.RES.45) Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, 107th Congress, U.S. Senate, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ On Agreeing to the Amendment (Byrd Amdt. No. 4869), 107th Congress, U.S. Senate, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ S.AMDT.4862 – Providing for Congressional Construction in the Consideration of the Joint Resolution (S.J.RES.45) Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, 107th Congress, U.S. Senate, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ On Agreeing to the Amendment (Levin Amdt. No. 4862), 107th Congress, U.S. Senate, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ S.AMDT.4865 – Providing for Congressional Amendment in the Consideration of the Joint Resolution (S.J.RES.45) Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, 107th Congress, U.S. Senate, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ On Agreeing to the Amendment (Byrd Amdt. No. 4865), 107th Congress, U.S. Senate, Library of Congress, 2002-10-10

- ^ Doe v. Bush Opinion by Judge Lynch 3/13/2003 Archived 2007-08-09 at the Wayback Machine Pages 3,4,23,25,26. Retrieved 8/7/2007.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen; Borger, Julian (2004-09-16). "Iraq war was illegal and breached UN charter, says Annan". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ "Iraq war illegal, says Annan". 16 September 2004 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ World Press: "The United Nations, International Law, and the War in Iraq" Retrieved 9/5/2007. "Resolution 1441 ultimately passed—by a vote of 15–0—because its ambiguous wording was able to placate all parties. <...> Resolution 1441 is ambiguous in two important ways. The first deals with who can determine the existence of a material breach. The second concerns whether another resolution, explicitly authorizing force, is needed before military action against Iraq may be taken."

- ^ UN Charter Article 39 http://www.un.org/en/documents/charter/chapter5.shtml Accessed 12/28/2011.

- ^ ASIL: Security Council Resolution 1441 on Iraq's Final Opportunity to Comply with Disarmament Obligations November, 2002. Retrieved 9/5/2007. "The language of 'material breach' in Resolution 1441 is keyed to Article 60 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which is the authoritative statement of international law regarding material breaches of treaties. Under Article 60 of the Vienna Convention, a material breach is an unjustified repudiation of a treaty or the violation of a provision essential to the accomplishment of the object or purpose of a treaty. Article 60 provides that a party specially affected by a material breach of a multilateral treaty may invoke it as a ground for suspending the operation of the treaty in whole or in part in the relations between itself and the defaulting state. <...> Security Council Resolution 687, adopted at the end of the Gulf War, includes a provision declaring a formal cease-fire between Iraq, Kuwait and the member states (such as the United States) cooperating with Kuwait in accordance with Resolution 678 (1990). Resolution 678 authorized member states to use all necessary means to restore international peace and security in the area, and thus provided the basis under international law for the allies' military action in the Gulf War. The determination in Resolution 1441 that Iraq is already in material breach of its obligations under Resolution 687 provides a basis for the decision in paragraph 4 (above) of Resolution 1441 that any further lack of cooperation by Iraq will be a further material breach. If Iraq, having confirmed its intention to comply with Resolution 1441, then fails to cooperate fully with the inspectors, it would open the way to an argument by any specially affected state that it could suspend the operation of the cease-fire provision in Resolution 687 and rely again on Resolution 678."

- ^ World Press: "The United Nations, International Law, and the War in Iraq" Retrieved 9/5/2007. "[On Dec. 16, 1998], U.S. and British warplanes launched air strikes against Iraq after learning that Iraq was continuing to impede the work of UNSCOM, the weapons inspectors sent to Iraq at the close of the Gulf War, and thus was not in compliance with Resolution 687. When the Security Council met that night to discuss whether individual member states could resort to force without renewed Security Council consent, it was clear that the Security Council members did not all agree on the legality of the U.S. and British resort to force. According to the press release from that meeting, the U.S. representative claimed his country's actions were authorized by previous council resolutions (as many in the Bush administration are arguing again today). The British delegate similarly argued that because Iraq had not complied with the terms of Resolution 687, military force was justified."

- ^ World Press: "The United Nations, International Law, and the War in Iraq" Retrieved 9/5/2007. "At that time, U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. John Negroponte said: 'This resolution contains no 'hidden triggers' and no 'automaticity' with respect to the use of force. If there is a further Iraqi breach, reported to the council by UNMOVIC, the IAEA, or a Member State, the matter will return to the council for discussion….[But] if the Security Council fails to act decisively in the event of further Iraqi violations, this resolution does not constrain any member state from acting to defend itself against the threat posed by Iraq or to enforce the relevant United Nations resolutions and protect world peace and security.' The British ambassador, Sir Jeremy Greenstock, agreed."

- ^ American Society of International Law: Security Council Resolution 1441 on Iraq's Final Opportunity to Comply with Disarmament Obligations November, 2002. http://www.asil.org/insigh92.cfm Archived 2012-02-04 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 12/28/2011.

- ^ US not allowed to speak for the entire council

- The United Nations, International Law, and the War in Iraq Rachel S. Taylor, World Press Review

- UN RESOLUTION 1441: COMPELLING SADDAM, RESTRAINING BUSH Archived 2006-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Professor Mary Ellen O'Connell, Moritz School of Law, Ohio State University, JURIST, November 21, 2002.

- ^ ASIL: Security Council Resolution 1441 on Iraq's Final Opportunity to Comply with Disarmament Obligations November, 2002. Retrieved 9/5/2007. "[T]he representative of Mexico (a current member of the Security Council) said after the vote on Resolution 1441 that the use of force is only valid as a last resort and with prior, explicit authorization from the Council. Mexico does not stand alone in taking that position. <...> It would be argued that, in light of the emphasis in the Charter on peaceful dispute settlement, Resolution 678 could not be used as an authorization for the use of force after twelve years of cease fire, unless the Security Council says so."

- ^ "In Historic, Bipartisan Move, House Votes To Repeal 2002 Iraq War Powers Resolution". 17 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Desiderio, Andrew (2021-07-20). "Unlikely Senate alliance aims to claw back Congress' foreign policy powers 'before it's too late'". Politico. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ^ "S.2391 – National Security Powers Act of 2021 117th Congress (2021–2022)". congress.gov. Law Library of Congress. July 20, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ McGovern, James P. (2021-09-30). "Text – H.R.5410 – 117th Congress (2021–2022): National Security Reforms and Accountability Act". congress.gov. Law Library of Congress. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ^ "H.R.5410 – National Security Reforms and Accountability Act 117th Congress (2021–2022)". congress.gov. Law Library of Congress. September 30, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ Yilek, Caitlin (March 16, 2023). "Senate advances bill to repeal Iraq war authorizations in bipartisan vote". CBS News.

- ^ "All Information (Except Text) for H.R.932 – To repeal the authorizations for use of military force against Iraq. 118th Congress (2023–2024)". congress.gov. Law Library of Congress. February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ "S.Amdt.427 to S.2226 118th Congress (2023–2024)". congress.gov. Law Library of Congress. July 13, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ "Amendments: S.2226 — 118th Congress (2023–2024)". congress.gov. Law Library of Congress. July 27, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Text of joint resolution as amended (PDF/details) in the GPO Statute Compilations collection

- Text of joint resolution as enacted (details) in the US Statutes at Large

- Iraq War Resolution, Roll Call Vote – House (clerk.house.gov)

- Iraq War Resolution, Roll Call Vote – Senate (senate.gov)

- Bill status and summary on Congress.gov

- President Signs Iraq Resolution, East Room Remarks

- Floor speeches

- Floor Speech of Sen Hillary Clinton (earthhopenetwork.net)

- Floor Speech of Sen Russ Feingold (feingold.senate.gov)

- Floor Speech of Sen Jay Rockefeller (rockefeller.senate.gov)

- Floor Speech of Rep Ron Paul (www.house.gov/paul)

- Floor Speech of Rep Pete Stark

- Floor Speech of Rep Dennis Kucinich

- Congressional Records related to the Congress' consent to the Authorization of the Use of Military Force in Iraq

Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002

View on GrokipediaBackground

Iraq's History of Aggression and Non-Compliance

Iraq, under Saddam Hussein, demonstrated a pattern of regional aggression beginning with the invasion of Iran on September 22, 1980, initiating the Iran-Iraq War that lasted until August 1988 and resulted in over one million casualties on both sides.[8] During this conflict, Iraq first used chemical weapons against Iranian combatants in 1983, escalating to large-scale deployments including mustard gas and nerve agents, with documented attacks causing thousands of Iranian military and civilian deaths.[9] Iraq also employed chemical weapons domestically, notably in the Anfal campaign against Kurdish populations, culminating in the Halabja attack on March 16, 1988, where approximately 5,000 civilians were killed by a mix of mustard gas and nerve agents. This aggression extended to the invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990, which Iraq justified through unsubstantiated claims of economic disputes and territorial rights but constituted a clear violation of international borders.[10] The United Nations Security Council responded immediately with Resolution 660, condemning the invasion and demanding Iraq's unconditional withdrawal of forces.) Subsequent resolutions imposed comprehensive economic sanctions under Resolution 661 and authorized a U.S.-led coalition to expel Iraqi forces via Resolution 678 in November 1990, leading to the 1991 Gulf War.[11][12] The Gulf War ceasefire, formalized in United Nations Security Council Resolution 687 on April 3, 1991, suspended hostilities contingent on Iraq's fulfillment of strict disarmament obligations, including the unconditional destruction, removal, or rendering harmless of all biological and chemical weapons, ballistic missiles with a range greater than 150 kilometers, and related production facilities, under international supervision.[13] The resolution also required Iraq to declare and renounce future development of such weapons and to accept ongoing monitoring by the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM). Iraq formally accepted these terms but engaged in systematic non-compliance, including false declarations, concealment of proscribed materials, and denial of access to sites.[14] UNSCOM's verification efforts from 1991 onward were repeatedly obstructed by Iraqi tactics such as delaying inspections, removing evidence, and intimidating personnel, leading to multiple standoffs and temporary suspensions of work.[15] By 1998, Iraq's defiance intensified, culminating in the expulsion of all UNSCOM and International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors on December 16, 1998, after barring access to presidential sites and other locations suspected of hiding dual-use equipment.[16] This action violated the ceasefire terms and prompted UN Security Council condemnation, followed by U.S. and UK airstrikes under Operation Desert Fox to degrade Iraq's weapons capabilities.[17] Parallel to inspection obstructions, Iraq evaded UN sanctions imposed since 1990 by smuggling oil and illicit trade, generating an estimated $4.4 billion in unauthorized revenue through surcharges on oil sales and kickbacks on import contracts under the Oil-for-Food program initiated in 1996.[18] These activities funded military rebuilding and dual-use infrastructure, undermining the sanctions' aim to enforce disarmament and demonstrating Iraq's persistent rejection of international oversight.[19] Such non-compliance reinforced perceptions of Iraq as a serial violator of ceasefires and resolutions, sustaining regional instability into the early 2000s.[12]Post-9/11 Context and Emerging Threats

The September 11, 2001, attacks, which killed 2,977 people, exposed vulnerabilities to asymmetric threats from non-state actors and prompted the United States to prioritize preventing catastrophic attacks by confronting state sponsors of terrorism and proliferators of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). This led to a doctrinal evolution toward preemption, as the U.S. could no longer rely solely on deterrence against regimes willing to arm terrorists with WMD.[20] The National Security Strategy of September 20, 2002, explicitly endorsed preemptive action, stating that "the United States will, if necessary, act preemptively" against emerging threats to deny hostile actors the opportunity to strike first.[21] In this context, Iraq emerged as a focal point due to its defiance of United Nations resolutions on disarmament and its potential to transfer WMD to terrorist groups amid the global jihadist surge post-9/11.[22] President George W. Bush's January 29, 2002, State of the Union address labeled Iraq part of an "axis of evil" with Iran and North Korea, emphasizing that these regimes and their terrorist allies were pursuing WMD to threaten peace, with Iraq specifically cited for seeking nuclear capabilities and biological agents.[23] The address underscored Iraq's role in enabling terrorism, warning that inaction risked empowering fanatics with tools for mass murder on the scale of 9/11 or worse.[23] Empirical evidence of Iraq's terror sponsorship reinforced the perceived urgency of regime change as a preventive measure. Saddam Hussein's government disbursed payments to families of Palestinian suicide bombers targeting Israeli civilians, raising the amount from $10,000 to $25,000 per family in April 2002 to incentivize such attacks.[24] Iraq also provided safe haven to the Abu Nidal Organization, a group responsible for attacks in 20 countries killing or injuring over 900 people, in violation of UN Security Council Resolution 687 prohibiting support for terrorism.[25] These actions positioned Iraq as a state enabler of networks that could align with al-Qaeda-like threats, justifying preemptive authorization to eliminate the risk.[22]U.S. Intelligence on Iraqi WMD Programs and Terrorism Links

The National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) issued in October 2002, titled "Iraq's Continuing Programs for Weapons of Mass Destruction," assessed with high confidence that Iraq maintained active chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons programs in violation of United Nations resolutions.[26] The NIE, produced by the CIA and other intelligence agencies including the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), judged that Baghdad possessed chemical weapons, including mustard agent, sarin, cyclosarin, and VX, with stockpiles estimated in the range of hundreds of metric tons based on historical production data and incomplete accounting from UN inspections.[27] Biological weapons programs were deemed ongoing, with Iraq retaining strains of anthrax, botulinum, and other agents, supported by defector reports of hidden facilities and procurement of dual-use equipment like fermenters.[28] Nuclear ambitions were evaluated as reconstituted, with Iraq pursuing uranium enrichment via gas centrifuges and acquiring high-strength aluminum tubes for rotors, corroborated by intercepted procurement attempts and defector testimony from figures like Khidir Hamza.[26] Delivery systems included ballistic missiles with ranges exceeding UN-permitted limits, such as the Al-Samoud and Ababil-100, evidenced by flight tests and engine imports.[28] These assessments relied heavily on human intelligence from defectors, signals intercepts, and analysis of Iraq's non-cooperation with UN inspectors, who were expelled in 1998 and denied readmission until late 2002 under limited terms.[29] For instance, Curveball's debriefings described mobile biological production units, while other sources detailed concealed chemical stockpiles moved to evade detection.[30] The NIE noted uncertainties due to limited access but emphasized Iraq's history of deception, including false declarations to UNSCOM, as causal factors inflating ambiguity rather than negating capabilities.[26] Post-invasion investigations by the Iraq Survey Group (ISG) under Charles Duelfer partially corroborated pre-war concerns, uncovering undeclared mobile laboratories initially assessed as biological production units—though later debated—and over 500 munitions containing degraded chemical agents like sarin and mustard, hidden from inspectors.[31] These finds aligned with intelligence on Saddam Hussein's intent to retain dual-use infrastructure for rapid reconstitution once sanctions lifted, without excusing his obstructions that precluded definitive verification.[32] On terrorism links, U.S. intelligence in 2002 identified operational ties between Iraq and al-Qaeda affiliates, including safe haven provided to senior al-Qaeda operatives in Baghdad for meetings with Iraqi intelligence services (IIS).[33] Reports detailed visits by figures like Abu Musab al-Zarqawi to Baghdad in 2002 for medical treatment and planning, under IIS protection, as well as financial and logistical support to the al-Qaeda-linked Ansar al-Islam group operating chemical weapons training camps in northern Iraq's Kurdish regions since September 2001.[34] Ansar al-Islam, which conducted assassinations and bombings against secular Kurds, received tacit Iraqi regime tolerance and shared ideological goals with al-Qaeda, evidenced by shared personnel and explosive expertise transfers.[35] While the NIE focused primarily on WMD, companion assessments highlighted these contacts as part of a pattern of Iraqi state sponsorship of terrorism, including payments to Palestinian suicide bombers' families, raising concerns of WMD proliferation risks to non-state actors.[36] Limitations in sourcing persisted, but declassified documents underscored Saddam's strategic outreach to jihadists amid post-9/11 isolation.[37]Content of the Resolution

Primary Authorizations and Objectives

The Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, enacted as Public Law 107-243, provided explicit authorization in Section 3(a) for the President to deploy United States Armed Forces as deemed necessary and appropriate to defend U.S. national security against the continuing threat posed by Iraq and to enforce all relevant United Nations Security Council resolutions concerning Iraq.[5] This authorization was conditioned on the President's prior determination that diplomatic efforts alone could not adequately address the threat, aligning with the resolution's preamble findings on Iraq's noncompliance with UN mandates, including those on weapons of mass destruction (WMD), since 1991.[6] Section 3(b) articulated the sense of Congress regarding the objectives of any such military action, emphasizing strict enforcement of UN resolutions to compel Iraq's disarmament of chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons and associated delivery systems; termination of Saddam Hussein's repressive policies toward the Iraqi populace, including human rights abuses and support for terrorism; and facilitation of a transition to representative self-government in Iraq post-regime change.[5] These objectives reflected congressional intent to address not only immediate security risks but also long-term regional stability, with the resolution underscoring Iraq's history of aggression and evasion of inspections as justification.[6] To ensure oversight, Section 4 mandated presidential reports to Congress at least every 60 days on matters relating to the resolution, including the status of diplomatic efforts, military actions, and progress toward the stated objectives, with initial notifications required before deploying forces and upon determining the threat's continuation.[5] The resolution became law on October 16, 2002, following passage by the House of Representatives on October 10, 2002, by a vote of 296-133, and by the Senate on October 11, 2002, by a vote of 77-23.[38][2][3]Enforcement Mechanisms and Conditions

The Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 included specific conditions requiring the President to determine that diplomatic and peaceful means alone would not adequately address the threat posed by Iraq or enforce relevant United Nations Security Council resolutions before deploying U.S. Armed Forces.[5] Under Section 3(b), the President was obligated to submit a certification to Congress stating that further reliance on such measures either failed to protect U.S. national security against Iraq's continuing threat or was unlikely to achieve compliance with United Nations resolutions, while ensuring consistency with ongoing actions against international terrorism, including those linked to the September 11, 2001, attacks.[5] This certification mechanism emphasized engagement with the United Nations framework, as the authorization explicitly referenced enforcement of resolutions such as United Nations Security Council Resolution 678 (1990) and subsequent measures demanding Iraq's disarmament and compliance.[5] Procedural safeguards mandated prompt notification to Congress following the introduction of U.S. forces into hostilities.[5] The President was required to notify Congress either before or within 48 hours after exercising the authority granted, detailing the circumstances necessitating the action.[5] Additionally, Section 5 directed the President to submit reports to Congress at least every 60 days on matters relevant to the resolution, including actions taken under the authorization, to maintain congressional oversight of ongoing operations.[5] Unlike broader authorizations for use of military force, such as the 2001 AUMF against those responsible for the September 11 attacks, the 2002 Iraq Resolution lacked an explicit termination date or sunset provision, but its scope was narrowly confined to defending against the specific threat posed by Iraq and enforcing pertinent United Nations resolutions.[5] The use of force was limited to what the President determined necessary and appropriate for these objectives, without extending to unrelated conflicts or perpetual engagements.[5] This targeted framing distinguished it from open-ended war powers, tying military actions directly to Iraq's non-compliance and weapons programs rather than granting indefinite authority.[5]Legislative History

Introduction and Initial Drafting

The Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 originated amid heightened U.S. concerns over Iraq's weapons programs following President George W. Bush's September 12, 2002, address to the United Nations General Assembly, where he warned of consequences for non-compliance with disarmament obligations. On September 19, 2002, Bush formally requested congressional authorization via a letter to Speaker of the House J. Dennis Hastert and Senate President pro tempore Robert Byrd, submitting proposed legislative text that would empower the President to employ U.S. Armed Forces to address the Iraqi threat and enforce pertinent United Nations Security Council resolutions.[39] The initial draft language was prepared within the executive branch, primarily by White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, granting the President discretion to determine the necessity of military action against Iraq's continuing threat to U.S. national security.[40] This version reflected a broad interpretation of executive authority under Article II of the Constitution, with limited explicit conditions tied to multilateral processes. Congressional consultations quickly followed, involving bipartisan leaders such as House Majority Leader Dick Armey (R-TX), House Minority Whip Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle (D-SD), and Senate Minority Leader Trent Lott (R-MS), who sought modifications to incorporate stronger references to United Nations compliance mechanisms and reporting requirements to the Congress.[41][42] By early October 2002, negotiations yielded a compromise draft that evolved from the administration's original by explicitly conditioning force on Iraq's failure to meet UN demands, while preserving presidential flexibility; this adjustment addressed Democratic concerns over unilateralism and aligned with parallel UN Security Council deliberations leading to Resolution 1441.[43] On October 2, 2002, the refined resolution was introduced in the House as H.J. Res. 114, sponsored by Hastert and 97 cosponsors, and promptly referred to the House International Relations Committee for markup.[1] This introduction marked the formal commencement of legislative deliberation, setting the framework for subsequent amendments and floor action.[44]House Proceedings and Amendments

The House of Representatives considered H.J. Res. 114 under the provisions of H. Res. 574, a special rule reported by the Rules Committee and adopted by voice vote on October 8, 2002, which structured debate over 17 hours equally divided between supporters and opponents while waiving points of order against the resolution's provisions. This framework permitted consideration of specified amendments but preserved the core authorization granting the president broad discretion to use force against Iraq's perceived threats, aligning with the majority's position that multilateral preconditions could delay responses to Saddam Hussein's non-compliance with disarmament obligations.[45] Floor debate intensified on October 10, 2002, with opponents proposing amendments to impose stricter limits. The Lee substitute amendment, offered by Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA), sought to replace the authorization entirely with a prohibition on using funds for military action absent a United Nations Security Council resolution determining further Iraqi material breach or a congressional declaration of war; it failed by a recorded vote of 15 yeas to 407 nays. Similarly, the Spratt substitute amendment, sponsored by Rep. John Spratt (D-SC), would have confined U.S. force to supporting UN weapons inspections and enforcing existing Security Council resolutions without endorsing regime change or independent presidential action; it was rejected 207–225. These defeats underscored the prevailing congressional consensus prioritizing executive flexibility amid intelligence assessments of Iraq's weapons programs and regional risks, as articulated in floor statements emphasizing the resolution's language on defending national security against Iraq's "continuing threat."[5] The resolution then passed the House later that day by a yea-and-nay vote of 296–133, including 215 of 223 Republicans and 81 of 208 Democrats, reflecting substantial cross-party alignment on the need for robust authorization despite dissent over potential unilateralism.[2]Senate Proceedings and Amendments

The Senate commenced floor debate on H.J. Res. 114, the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, on October 9, 2002, following its passage in the House.[46] Proceedings focused on amendments aimed at constraining the resolution's scope, particularly by conditioning U.S. military action on United Nations involvement or alternative diplomatic measures. Senator Robert C. Byrd (D-WV) introduced multiple amendments to mandate full UN Security Council backing or to affirm that the resolution did not supersede the UN Charter and relevant resolutions, emphasizing multilateral constraints on unilateral U.S. action.[47] These proposals, including one to insert language preserving UN primacy, were rejected during votes on October 10, 2002, as supporters argued they unduly limited presidential flexibility in addressing Iraq's non-compliance with existing UN mandates.[47] Senator Carl Levin (D-MI) offered an amendment establishing an inspections-first approach, authorizing force only if Iraq refused unrestricted access under a strengthened new UN resolution demanding compliance with weapons inspections.[48] This substitute, which sought to prioritize renewed UN inspections over immediate military options, was defeated on October 10, 2002, by a vote of 24-75, with opponents contending it weakened deterrence against Iraq's evasion tactics.[49] Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) proposed Amendment No. 4865 to redefine the authorization's trigger from Iraq's "continuing threat" to an "imminent threat" specifically from weapons of mass destruction, aiming to narrow the conditions for force while incorporating limited humanitarian safeguards in post-action planning.[50] The amendment's core restrictions were not adopted, though minimal language on humanitarian assistance and regional stability was retained in the resolution's sense-of-Congress provisions, reflecting compromise on civilian protection concerns without altering the primary authorization.[5] The Senate approved the resolution without further restrictive amendments on October 11, 2002, by a vote of 77-23.[3] Among the yes votes were key Democrats including Senators Joe Biden (D-DE) and Hillary Clinton (D-NY), who justified support based on intelligence assessments of Iraq's weapons of mass destruction programs and defiance of UN inspections.[51][52]Final Votes and Enactment

The House of Representatives passed H.J. Res. 114 on October 10, 2002, by a vote of 296 to 133, with 215 Republicans and 81 Democrats voting in favor, alongside 126 Democrats and 6 Republicans opposed.[53] The Senate followed on October 11, 2002, approving the identical text without amendments by a margin of 77 to 23, including 48 Republicans, 29 Democrats, and both independents in support, against 21 Democrats and 2 Republicans.[3]| Chamber | Date | Yea | Nay | Party Breakdown (Yea) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| House | October 10, 2002 | 296 | 133 | 215 R, 81 D |

| Senate | October 11, 2002 | 77 | 23 | 48 R, 29 D, 2 I |

.svg/250px-Great_Seal_of_the_United_States_(obverse).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Great_Seal_of_the_United_States_(obverse).svg.png)