Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rankine cycle

View on Wikipedia

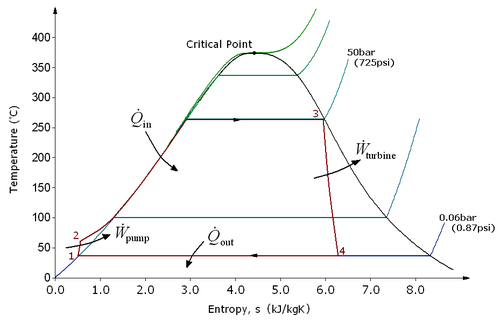

1. Pump, 2. Boiler, 3. Turbine, 4. Condenser

| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

The Rankine cycle is an idealized thermodynamic cycle describing the process by which certain heat engines, such as steam turbines or reciprocating steam engines, allow mechanical work to be extracted from a fluid as it moves between a heat source and heat sink. The Rankine cycle is named after William John Macquorn Rankine, a Scottish polymath professor at Glasgow University.

Heat energy is supplied to the system via a boiler where the working fluid (typically water) is converted to a high-pressure gaseous state (steam) in order to turn a turbine. After passing over the turbine the fluid is allowed to condense back into a liquid state as waste heat energy is rejected before being returned to boiler, completing the cycle. Friction losses throughout the system are often neglected for the purpose of simplifying calculations as such losses are usually much less significant than thermodynamic losses, especially in larger systems.

Description

[edit]The Rankine cycle closely describes the process by which steam engines commonly found in thermal power generation plants harness the thermal energy of a fuel or other heat source to generate electricity. Possible heat sources include combustion of fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas, and oil, use of mined resources for nuclear fission, renewable fuels like biomass and ethanol, and energy capture of natural sources such as concentrated solar power and geothermal energy. Common heat sinks include ambient air above or around a facility and bodies of water such as rivers, ponds, and oceans.

The ability of a Rankine engine to harness energy depends on the relative temperature difference between the heat source and heat sink. The greater the differential, the more mechanical power can be efficiently extracted out of heat energy, as per Carnot's theorem.

The efficiency of the Rankine cycle is limited by the high heat of vaporization of the working fluid. Unless the pressure and temperature reach supercritical levels in the boiler, the temperature range over which the cycle can operate is quite small. As of 2022, most supercritical power plants adopt a steam inlet pressure of 24.1 MPa and inlet temperature between 538°C and 566°C, which results in plant efficiency of 40%. However, if pressure is further increased to 31 MPa the power plant is referred to as ultra-supercritical, and one can increase the steam inlet temperature to 600°C, thus achieving a thermal efficiency of 42%.[1] This low steam turbine entry temperature (compared to a gas turbine) is why the Rankine (steam) cycle is often used as a bottoming[clarification needed] cycle to recover otherwise rejected heat in combined-cycle gas turbine power stations. The idea is that very hot combustion products are first expanded in a gas turbine, and then the exhaust gases, which are still relatively hot, are used as a heat source for the Rankine cycle, thus reducing the temperature difference between the heat source and the working fluid and therefore reducing the amount of entropy generated by irreversibility.

Rankine engines generally operate in a closed loop in which the working fluid is reused. The water vapor with condensed droplets often seen billowing from power stations is created by the cooling systems (not directly from the closed-loop Rankine power cycle). This "exhaust" heat is represented by the "Qout" flowing out of the lower side of the cycle shown in the T–s diagram below. Cooling towers operate as large heat exchangers by absorbing the latent heat of vaporization of the working fluid and simultaneously evaporating cooling water to the atmosphere.

While many substances can be used as the working fluid, water is usually chosen for its simple chemistry, relative abundance, low cost, and thermodynamic properties. By condensing the working steam vapor to a liquid, the pressure at the turbine outlet is lowered, and the energy required by the feed pump consumes only 1% to 3% of the turbine output power. These factors contribute to a higher efficiency for the cycle. The benefit of this is offset by the low temperatures of steam admitted to the turbine(s). Gas turbines, for instance, have turbine entry temperatures approaching 1500 °C. However, the thermal efficiencies of actual large steam power stations and large modern gas turbine stations are similar.

The four processes in the Rankine cycle

[edit]

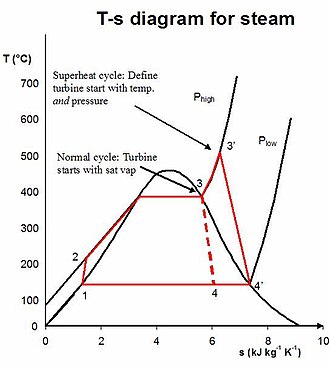

There are four processes in the Rankine cycle. The states are identified by numbers (in brown) in the T–s diagram.

| Name | Summary | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Process 1–2 | Isentropic compression | The working fluid is pumped from low to high pressure. As the fluid is a liquid at this stage, the pump requires little input energy. |

| Process 2–3 | Constant pressure heat addition in boiler | The high-pressure liquid enters a boiler, where it is heated at constant pressure by an external heat source to become a dry saturated vapour. The input energy required can be easily calculated graphically, using an enthalpy–entropy chart (h–s chart, or Mollier diagram), or numerically, using steam tables or software. |

| Process 3–4 | Isentropic expansion | The dry saturated vapour expands through a turbine, generating power. This decreases the temperature and pressure of the vapour, and some condensation may occur. The output in this process can be easily calculated using the chart or tables noted above. |

| Process 4–1 | Constant pressure heat rejection in condenser | The wet vapour then enters a condenser, where it is condensed at a constant pressure to become a saturated liquid. |

In an ideal Rankine cycle the pump and turbine would be isentropic: i.e., the pump and turbine would generate no entropy and would hence maximize the net work output. Processes 1–2 and 3–4 would be represented by vertical lines on the T–s diagram and more closely resemble that of the Carnot cycle. The Rankine cycle shown here prevents the state of the working fluid from ending up in the superheated vapor region after the expansion in the turbine, [1] which reduces the energy removed by the condensers.

The actual vapor power cycle differs from the ideal Rankine cycle because of irreversibilities in the inherent components caused by fluid friction and heat loss to the surroundings; fluid friction causes pressure drops in the boiler, the condenser, and the piping between the components, and as a result the steam leaves the boiler at a lower pressure; heat loss reduces the net work output, thus heat addition to the steam in the boiler is required to maintain the same level of net work output.

Variables

[edit]| Heat flow rate to or from the system (energy per unit time) | |

| Mass flow rate (mass per unit time) | |

| Mechanical power consumed by or provided to the system (energy per unit time) | |

| Thermodynamic efficiency of the process (net power output per heat input, dimensionless) | |

| Isentropic efficiency of the compression (feed pump) and expansion (turbine) processes, dimensionless | |

| The "specific enthalpies" at indicated points on the T–s diagram | |

| The final "specific enthalpy" of the fluid if the turbine were isentropic | |

| The pressures before and after the compression process |

Equations

[edit]defines the thermodynamic efficiency of the cycle as the ratio of net power output to heat input. As the work required by the pump is often around 1% of the turbine work output, it can be simplified:

Each of the next four equations[1] is derived from the energy and mass balance for a control volume.

When dealing with the efficiencies of the turbines and pumps, an adjustment to the work terms must be made:

Real Rankine cycle (non-ideal)

[edit]

In a real power-plant cycle (the name "Rankine" cycle is used only for the ideal cycle), the compression by the pump and the expansion in the turbine are not isentropic. In other words, these processes are non-reversible, and entropy is increased during the two processes. This somewhat increases the power required by the pump and decreases the power generated by the turbine.[2]

In particular, the efficiency of the steam turbine will be limited by water-droplet formation. As the water condenses, water droplets hit the turbine blades at high speed, causing pitting and erosion, gradually decreasing the life of turbine blades and efficiency of the turbine. The easiest way to overcome this problem is by superheating the steam. On the T–s diagram above, state 3 is at a border of the two-phase region of steam and water, so after expansion the steam will be very wet. By superheating, state 3 will move to the right (and up) in the diagram and hence produce a drier steam after expansion.

Variations of the basic Rankine cycle

[edit]The overall thermodynamic efficiency can be increased by raising the average heat input temperature

of that cycle. Increasing the temperature of the steam into the superheat region is a simple way of doing this. There are also variations of the basic Rankine cycle designed to raise the thermal efficiency of the cycle in this way; two of these are described below.

Rankine cycle with reheat

[edit]

The purpose of a reheating cycle is to remove the moisture carried by the steam at the final stages of the expansion process. In this variation, two turbines work in series. The first accepts vapor from the boiler at high pressure. After the vapor has passed through the first turbine, it re-enters the boiler and is reheated before passing through a second, lower-pressure, turbine. The reheat temperatures are very close or equal to the inlet temperatures, whereas the optimal reheat pressure needed is only one fourth of the original boiler pressure. Among other advantages, this prevents the vapor from condensing during its expansion and thereby reducing the damage in the turbine blades, and improves the efficiency of the cycle, because more of the heat flow into the cycle occurs at higher temperature. The reheat cycle was first introduced in the 1920s, but was not operational for long due to technical difficulties. In the 1940s, it was reintroduced with the increasing manufacture of high-pressure boilers, and eventually double reheating was introduced in the 1950s. The idea behind double reheating is to increase the average temperature. It was observed that more than two stages of reheating are generally unnecessary, since the next stage increases the cycle efficiency only half as much as the preceding stage. Today, double reheating is commonly used in power plants that operate under supercritical pressure.

Regenerative Rankine cycle

[edit]

The regenerative Rankine cycle is so named because after emerging from the condenser (possibly as a subcooled liquid) the working fluid is heated by steam tapped from the hot portion of the cycle. On the diagram shown, the fluid at 2 is mixed with the fluid at 4 (both at the same pressure) to end up with the saturated liquid at 7. This is called "direct-contact heating". The Regenerative Rankine cycle (with minor variants) is commonly used in real power stations.

Another variation sends bleed steam from between turbine stages to feedwater heaters to preheat the water on its way from the condenser to the boiler. These heaters do not mix the input steam and condensate, function as an ordinary tubular heat exchanger, and are named "closed feedwater heaters".

Regeneration increases the cycle heat input temperature by eliminating the addition of heat from the boiler/fuel source at the relatively low feedwater temperatures that would exist without regenerative feedwater heating. This improves the efficiency of the cycle, as more of the heat flow into the cycle occurs at higher temperature.

Organic Rankine cycle

[edit]The organic Rankine cycle (ORC) uses an organic fluid such as n-pentane[3] or toluene[4] in place of water and steam. This allows use of lower-temperature heat sources, such as solar ponds, which typically operate at around 70 –90 °C.[5] The efficiency of the cycle is much lower as a result of the lower temperature range, but this can be worthwhile because of the lower cost involved in gathering heat at this lower temperature. Alternatively, fluids can be used that have boiling points above water, and this may have thermodynamic benefits (See, for example, mercury vapour turbine). The properties of the actual working fluid have great influence on the quality of steam (vapour) after the expansion step, influencing the design of the whole cycle.

The Rankine cycle does not restrict the working fluid in its definition, so the name "organic cycle" is simply a marketing concept and the cycle should not be regarded as a separate thermodynamic cycle.

Supercritical Rankine cycle

[edit]The Rankine cycle applied using a supercritical fluid[6] combines the concepts of heat regeneration and supercritical Rankine cycle into a unified process called the regenerative supercritical cycle (RGSC). It is optimised for temperature sources 125–450 °C.

See also

[edit]- Brayton cycle

- Power loss in cogeneration mode with steam extraction

References

[edit]- ^ Ohji, A.; Haraguchi, M. (2022-01-01), Tanuma, Tadashi (ed.), "2 - Steam turbine cycles and cycle design optimization: the Rankine cycle, thermal power cycles, and integrated gasification-combined cycle power plants", Advances in Steam Turbines for Modern Power Plants (Second Edition), Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy, Woodhead Publishing, pp. 11–40, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-824359-6.00020-2, ISBN 978-0-12-824359-6, retrieved 2023-07-06

- ^ Guruge, Amila Ruwan (2021-02-16). "Rankine Cycle". Chemical and Process Engineering. Retrieved 2023-02-15.

- ^ Canada, Scott; G. Cohen; R. Cable; D. Brosseau; H. Price (2004-10-25). "Parabolic Trough Organic Rankine Cycle Solar Power Plant" (PDF). 2004 DOE Solar Energy Technologies. Denver, Colorado: US Department of Energy NREL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ Batton, Bill (2000-06-18). "Organic Rankine Cycle Engines for Solar Power" (PDF). Solar 2000 conference. Barber-Nichols, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ Nielsen et al., 2005, Proc. Int. Solar Energy Soc.

- ^ Moghtaderi, Behdad (2009). "An Overview of GRANEX Technology for Geothermal Power Generation and Waste Heat Recovery". Australian Geothermal Energy Conference 2009. Inc.

- ^Van Wyllen 'Fundamentals of thermodynamics' (ISBN 85-212-0327-6)

- ^Wong 'Thermodynamics for Engineers',2nd Ed.,2012, CRC Press, Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, London, New York. (ISBN 978-1-4398-4559-2)

- Moran & Shapiro 'Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics' (ISBN 0-471-27471-2)

- Wikibooks Engineering Thermodynamics